Make No Mistake, the Ongoing Congestion Pricing Delay is Environmental Racism

Subway tunnels (photo: Governor's Office)

How many of our city's children need to suffer while the MTA conducts a 16-month ‘environmental review’ to implement congestion pricing in New York City?

Throughout 2020 and into this year, our city and state elected officials proclaimed in the face of COVID-19 and racial justice protests that they were ready to tackle the problematic issues generations of New Yorkers experienced—among them, solving the structural inequities caused by environmental racism and the harm that it does to our kids.

Back in 2019, the Union of Concerned Scientists concluded that the highways New York historically placed near communities of color "exacerbate lung and heart ailments, cause asthma attacks, and lead to both increased hospitalizations and mortality from cardiovascular diseases." Having housing near highways and disinvestments in public transportation worsened exposure to pollutants in these communities.

A deeply regrettable outcome of these decisions made our communities of color more susceptible to respiratory illnesses, like COVID-19, where well over 4,000 of our city's children lost a parent due to the pandemic (according to a study of the first wave, in 2020). And to the surprise of no one, that initial data showed one in 600 Black children and one in 700 Hispanic children lost parents due to COVID, double the rate compared to one in 1,500 white families. Another statistical example of the human consequences of our society's enduring prejudices.

The long-term effects of losing a parent will be hard to overcome. Children who experience parental loss at a young age battle early and persistent negative impacts on every aspect of their lives that stunt their social and emotional development. Among them, dealing with early-onset depression that continues throughout the person's lifetime.

And that's not all. Pollution continues harming their ability to learn and thrive, while making kids more susceptible to the next pandemic, or even more ‘regular’ illnesses, like the seasonal flu.

The Inter-American Development Bank conducted a study of 3,880 schools near pollutant-heavy areas and found that air pollution increased morbidity and mortality among children. Another study of schoolchildren by the Brookings Institute further validated those findings showing persistent exposure to air pollution increased fatigue, absenteeism, attention problems, poor test scores, and higher suspension rates.

It doesn't have to be this way.

Congestion pricing — set to be implemented in Manhattan south of 61st Street but impacting the entire city — will reduce car traffic, improve air quality, and help limit traffic crashes while increasing investments and access to our mass transportation system for the betterment of all New Yorkers.

There is no time to wait, and a 16-month review process is simply unacceptable. New York leaders must take action now to reduce that timeframe and get congestion pricing implemented as soon as possible.

The issues highlighted so starkly during 2020 have not gone away, and no action has been taken that resolves them, or even addresses them in a truly systemic fashion to improve health outcomes for our kids. But, we can embrace solutions that are ready for implementation, and congestion pricing is one of them.

The impetus is now on our elected leaders to expedite this plan for this generation of New York City kids. And the next.

***

Denny Salas is a former candidate for City Council who advocates for increasing affordable housing, pedestrianizing New York City streets, and eliminating structural inequities. On Twitter: @realdennysalas.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

‘Vigilante’ Mayoral Candidate Narrative Obscures History of New York City Resident Patrols

Curtis Sliwa & the Guardian Angels (photo: @CurtisSliwa)

Curtis Sliwa, the Republican nominee for New York City mayor, has portrayed himself as a police advocate and crimefighter dating back to his founding of the Guardian Angels in the late 1970s. But the image Sliwa has crafted of himself as the original civilian crimefighter distorts his role with the renegade patrol group.

While the Angels – a group of largely young African-American and Latino New Yorkers that began patrolling subways – may have been the most well-known volunteer crime-fighting group in the city – they were far from the first. They emerged only after wide swaths of New Yorkers pioneered a movement in which residents took to patrolling city streets. And it was Sliwa’s own deceitful tactics and bombastic deriding of law enforcement and officials while leading the Angels that helped facilitate the demise of this grassroots anti-crime movement that had been flourishing until that point.

In the mid-1960s, for example, Jewish residents of Crown Heights formed the Maccabees, the first citizen patrol of this time. Each night, hundreds of volunteers escorted residents and served as “crime-spotters” for the police in cars equipped with two-way radios.

Similar volunteer patrols grew in the years ahead. By the end of 1972, there were an estimated 15,000 volunteers in tenant and neighborhood patrols and at least 75 citizen car patrols.

New Yorkers formed these patrols out of deep concerns about rising crime. Homicides, for example, nearly tripled to 1,117 between 1960 and 1970. Many residents believed that the police – whether because they were outnumbered, inefficient, or just corrupt – were “not sufficient to check crime in our community,” as one group of Brooklyn residents put it.

For many whites, the city’s growing populations of color heightened fears about crime. But patrols also spread throughout African-American neighborhoods. In the early 1970s in Bedford-Stuyvesant, for example, 73 community groups came together to patrol residential areas, while Black shopkeepers formed their own patrol to stop holdups.

Citizen watches also spread throughout public housing projects, where by the end of the 1970s, nearly 13,000 residents patrolled across 127 developments. Residents of color commonly demanded not just more but better policing as well as greater educational and job opportunities that would address crime at its roots.

Though initially skeptical of these community patrols, officials ultimately switched course due to the city’s deteriorating economy. Officials supported these patrols as a low-cost means to combat crime as city budgets were constrained. In 1973, for example, Mayor John Lindsay initiated a program that provided matching funds for citizen patrols to purchase equipment like walkie-talkies and uniforms.

As the city’s financial conditions worsened over the 1970s, the police stepped up their support as well, especially through training programs. By late 1977, more than 32,000 residents had gone through the NYPD’s block watcher training while a Civilian Observation Patrol (COP) trained citizen patrols. By 1977, COP groups were active in nearly 65% of precincts.

Most critical to the growth of citizen patrols, however, was the thousands of residents who believed their volunteerism was necessary – from the residents who patrolled six nights a week in Hollis Hills to the dozens of community groups in the African-American areas of Crown Heights and Flatbush who patrolled on foot and by car in uniform with radios connected to the local precinct.

It was this environment – of a city gripped by widespread concerns about crime and by the belief that police alone could not stop it – that forged the opening for Sliwa and the Guardian Angels to move onto the subways and capture the attention of the city and the country. Indeed, by the time the Angels gained public prominence, volunteer anti-crime groups had become established across the city’s landscape. Citizen patrols numbered 60 in 1977 and 135 in 1982; the overall number of residents involved in anti-crime programs by that time doubled to 150,000.

Once the Angels emerged, Sliwa’s consistent criticism of the failures of officials and police to effectively address crime certainly had merit, but they were undermined by his arrogance and bravado as well as his self-promotion tactics, which were designed to keep himself in the media spotlight (a number of these schemes were faked, as Sliwa later admitted).

What’s more, Sliwa’s antics helped cause officials to become more cautious of supporting grassroots anti-crime initiatives. City officials dismissed the Angels as vigilantes, but also began pulling back on resources for resident patrols more generally, instead focusing more narrowly on boosting police funding. Over the 1980s, the number of residents involved in patrols ultimately declined by one third and the number of active block watchers dropped by over 80%.

Indeed, by many measures, Sliwa did more to help usher in the decline of the broader citizen patrol movement, rather than being the catalyst that he portrays himself to be.

Today, the city once again finds itself awash in concerns about public safety, despite crime rates remaining far lower than decades earlier and despite perceptive criticisms of police. And Sliwa’s position once again threatens community safety.

Sliwa’s campaign has expunged his criticisms of policing he once made from his biography while portraying him as having been the singular New Yorker who “had to do something” when all others had “resigned themselves to the reality” of crime to buttress his law and order credentials and call for increased police. This false narrative not only omits the richer and more complex history of citizen patrols in New York. It also deliberately diminishes proposed responses to crime that have emerged from within New York’s neighborhoods today that go beyond Sliwa’s position that the predominant path to safety lays with more police.

***

Benjamin Holtzman is an Assistant Professor of History at Lehman College and author of The Long Crisis: New York City and the Path to Neoliberalism. On Twitter @holtzman_b.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Private Sector Must Stand Up for Voting Rights; Here’s How

Voting (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

We are in the midst of a Republican-led national campaign to restrict voting. According to the Brennan Center, 18 states have already enacted 30 laws this year that will make voting more difficult. The federal government has the ability to pass national laws to mitigate the effects of many state-level restrictions, such as the “For the People Act” and the “John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.” But due to the lack of a clear majority for both bills, we cannot wait for the federal government to act. We must mobilize the private sector to counteract the effects of restrictive voting policies.

Across the country, laws have been enacted that restrict voting access by shortening the hours of operation of poll sites, reducing the number of drop boxes available for completed absentee ballots, preventing the distribution of water and food to voters waiting in long lines, purging voter rolls, preventing proactive outreach regarding absentee voting, and more.

The private sector can and should work to mitigate the effects of these policies. Companies should commit to policies advanced by Time to Vote, for example, which mobilizes CEOs and private company leadership teams to pledge that employees will be given the time they need to cast their ballots. More specifically, companies big and small must offer paid time off to vote. This can be done in many ways: allowing for late arrival to work or early departure from work in order to cast one’s vote without penalty and with pay; educating employees internally about local elections, deadlines to register to vote, time frames to conduct one’s vote, etc; facilitating the ability to register to vote on site in the workplace; and more.

The beauty of such policies are many. First, working to counteract barriers to vote is nonpartisan, and thus does not politicize the workplace. Second, there is an interest convergence at play. If the need for voting rights and election integrity are essential to the operation and preservation of our democracy, the private sector has every interest in preserving these rights. Our democracy has created the greatest economy the world has ever known. Private companies operate within and benefit from the stability and integrity of our democracy.

And let’s be clear that this is also about racial justice. Restrictive voting measures disproportionally disenfranchise racial minorities, and in fact, are insidiously designed to do just that. Those corporations that do not take a clear stand against racial injustice and enact policies to further justice and equity are on a sinking ship as the demographics of the country change and as younger generations demand some level of socio-economic activism from private companies.

The distortion of our democracy as reflected in less participation by racial minorities threatens the sustainability of our democracy, and the environment in which private companies can achieve prosperity.

So what can be done on an individual level? Talk to your employer about programs like Time to Vote. The fact that nearly 2,000 companies across the country have signed on to the pledge gives it legitimacy, and will allow your company to be in the good graces of many other reputable firms. Demand that your company and other large, national firms do not donate to candidates at the local, state, or federal level that do not protect voting rights. Speak out on social media about the importance of the private sector when the government fails to protect our rights.

And remember: none of our rights to participate in our democracy are safe until all of our rights to participate in our democracy are safe.

***

Natalie Diaz is Chief of Staff at Time Equities, Inc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Voter Privacy Violations Will Continue Until Government Acts to Fix Them

Voters at the polls (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Voters at the polls (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Voter data reporting laws must provide for voter privacy. Our elections are some of the most secure in all of the world, and at a time when voter confidence faces threats from false claims of fraud, it’s all the more important that voter data be held in a secure way. As cities and states seek to enhance confidence in their organizational competency and the validity of elections, statutes demanding access to auditable public election records are increasingly commonplace.

Election data is a public good because it allows any interested person to double check ballot tabulations and conduct useful research on voter behavior. But without sufficient data security provisions, releasing voter data risks our protections guaranteeing the right to cast a secret ballot.

New York City just experienced such a lapse. Three researchers used two publicly available data sets and two lines of code to identify how 378 voters voted in the 2021 primary elections. As The New York Times recently reported, the disclosure included high-profile voters that expressed their dismay at the invasion of their privacy.

We are those researchers. Our ability to identify these voters and their choices does not rely on any hyper-technical skills, it was based on simply knowing where to look and how to expose data privacy lapses in a straightforward way. Other people, with a variety of reasons in mind, can and will be able to do the same thing in elections moving forward unless governments act to shore up their data practices. Fortunately, the technical solutions are easy to implement. The political solutions, however, must be addressed first.

On August 18, 2021, the New York City Board of Elections released vote records for the June primary election. The records released from the first ranked-choice voting election in New York City are called the cast vote record (CVR). Each CVR lists the ranked choices each voter cast in the Democratic or Republican primary election as well as the Assembly District (AD) and Election District (ED) for each ballot. To keep voter choices private, a de-identifying step is taken in which CVRs are associated with numerical identifiers rather than voter names before they are released publicly.

But, in some AD/ED voter locations only one person showed up to vote in the election. In those cases, we were able to use the New York State voter file (obtained through a standard Freedom of Information Law request) to check which registered voters participated in the election at all. The voter file contains the data on which voter participates in which election, but nothing about individual choices. However, when there is only one voter who turned out for a particular party in a particular AD/ED, it becomes clear who voted and for which candidates in each election.

Given this alarming lapse in voter privacy we contacted the New York City Board of Elections hoping to point out the error and suggest a simple-to-implement technical solution.

We spoke with the BOE and brought this issue to their attention through a phone call with a bipartisan delegation from the board as well as the BOE General Counsel, Hemalee Patel, on September 13, 2021. The BOE was aware that this problem may arise but the representatives noted that we were the first research team to find it and bring it to their attention. They indicated that this voter privacy problem is a result of the reporting requirements that mandate the board makes the data publicly available in a certain format, with no flexibility to group single-voter AD/EDs. According to the BOE, this problem can only be corrected by a change to the New York City Charter or New York State Law.

The solution to this privacy issue is not to restrict the data sources employed in our analysis. These data sources -- both the CVR and the New York State voter file -- are integral to evaluating the performance of elections. The CVR is necessary in order for people to audit the Board of Elections and its tabulations, while the voter file is necessary for voting rights groups to ensure that districts are drawn fairly and equitably to ensure proper representation, among other reasons.

If the voter file is restricted, it will effectively only be available to political parties, super PACs, interest groups, and political campaigns due to their special access and ability to pay. Instead, if data reporting requirements are changed to require very low single-voter AD/EDs to be bundled with neighboring AD/EDs, this identifying operation becomes nearly impossible in cases where pooled voters cast votes for different candidates. Similar measures are taken by the Census Bureau every ten years in order to protect privacy in rural areas and in small city blocks, where random “noise” is injected into the data or entries are swapped between geographies or bundled so that small, singularly identifiable entries are not released.

Similarly, the solution is not to end the practice of ranked-choice voting. While this came about through the results of the election, there is nothing preventing us from conducting this same operation in an entirely different system, whether it be a traditional plurality system or an alternative system such as approval voting, single transferable vote, or a party-list voting. The issue is the data reporting requirements, not the data itself.

It is our hope that by raising this issue we may better protect the privacy of voters in New York City, and voters around the United States. When issues of voter data and privacy are involved we need more than elected officials and appointed bureaucrats at the table — academic researchers, lawyers, voting scholars, and election administrators must be involved as we formulate and implement government policy on voter privacy.

This operational fix would be incredibly simple from a technical standpoint and would not cost the New York City Board of Elections any more than a few minutes of staff time. But importantly, it would protect the privacy of these voters, who cast their ballots under the good-faith assumption that their privacy is protected by law. The City Council or the State Legislature needs to act so that boards of elections can implement better data stewardship practices in the future.

***

Lindsey Cormack is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Stevens Institute of Technology. Jesse T. Clark is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Electoral Innovation Lab, Princeton University. On Twitter @DCinbox and @electionclark.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

An Assignment for the Federal Government: Tackle Student Debt and Expand Educational Opportunity by Doubling Pell Grants

Students graduating (photo: Bruce Gilbert/Forham Alumni)

For nearly 50 years, the Pell Grant has been the centerpiece of federal student aid, helping individuals most in need of financial support to attend the college or university of their choice. Pell Grants help more than 370,000 New York students and their families afford a college education every year. They are proven to be the most effective and equitable investment the federal government can make in students. Simply put, investing in Pell Grants tackles student debt head-on.

However, the federal government has not made a meaningful increase to Pell Grants in well over a decade. In the interim, colleges and universities have worked hard to pick up the slack, but the challenges of inadequate funding persist.

New York’s private, not-for-profit colleges and universities are doing their part to make higher education more accessible and affordable by providing more than $6.4 billion in financial aid each year to students of all income levels. In fact, 66% of students who attend New York’s private, not-for-profit colleges and universities come from families earning less than $125,000 a year. Despite best efforts from institutions, the affordability gap has become a greater barrier as Pell Grants have remained stagnant. The federal government must step up and do its part.

The time for Congress to act is now but lawmakers should not pick winners and losers by only investing in students at some colleges. Doubling the maximum Pell Grant to $13,000 is the fairest and most efficient and equitable way for Congress to provide higher education funding to all students who need it. Doubling Pell Grants would enable thousands more students, at both community colleges and four-year colleges, to receive the college education of their dreams while reducing student loan debt.

This investment would have sweeping benefits for students throughout New York and across the nation. Congress has the opportunity to make a critical investment in our students and the social and economic wellbeing of the country itself.

Pell Grants were overwhelmingly successful when first introduced in 1972 because they covered a significant percentage of college tuition costs for students. However, the cost of high-quality higher education has risen and Pell Grants have not kept pace. Doubling Pell Grants is the most effective way to restore that balance and offer more students a sizable financial aid grant that provides meaningful help with college costs.

The Biden Administration has laid forth a tremendous opportunity for students in New York and across the country to receive an affordable college education of their choice. Doubling the Pell Grant should be Congress’s top higher education priority. It should be accomplished immediately, and certainly by the program’s 50th anniversary on June 23, 2022.

***

by: Lola W. Brabham, President, Commission on Independent Colleges and Universities

Henry C. “Hank” Foley, President, New York Institute of Technology

Miguel Martinez-Saenz, President, St. Francis College

Father Joseph M. McShane, S.J., President, Fordham University

Laura Sparks, President, The Cooper Union

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Cordell Cleare Poised to Join Storied History of Harlem-West Side Senate District

(l-r) Basil Paterson, Carl McCall, Brian Benjamin, Cordell Cleare

Cordell Cleare recently received the Democratic nomination to replace Lieutenant Governor Brian Benjamin in the State Senate after his appointment by Governor Hochul. Cleare is almost certain to win the special election that will be held with the general election on November 2.

She will succeed the legacy of Constance Baker Motley, Basil Paterson, Carl McCall, and David Paterson, some of the prominent senators who have represented the district. Combining much of Harlem with the Upper West Side and other adjacent neighborhoods, the district has a rich history of noteworthy senators.

It was not until 1953 when Julius Archibald became the first African-American to serve in the New York State Senate. (Edward Johnson, a former slave, was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1917.) Archibald won a narrow victory in the 1952 primary, a margin of just 207 votes against incumbent Harold Panken, who was backed by the Tammany machine including the African-American Carver Democratic Club led by J. Raymond Jones.

Whites constituted 48% of the district’s voters at that time, but Archibald, who was a leader in the NAACP running on a civil rights platform, squeaked to victory with a coalition assembled by the West Side reform leader Robert Blaikie with support from anti-Tammany Congressmen Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr. and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

Archibald’s slim victory in the primary sent a clear message to the party leadership: an African-American should represent Harlem in the Senate district it shared with the West Side. That has been the case in every election since that historic breakthrough in 1953.

The Tammany leaders promptly regrouped and easily won the nomination for one of their own, James Lopez Watson, who swamped Archibald in the 1954 primary. Watson served in the State Senate until 1963, when he decided on a judicial career and was elected to the Civil Court — a judicial seat first held by his father, James S. Watson, who in 1930 was the first African-American elected judge in New York. President Lyndon Johnson subsequently appointed the younger Watson as the first African-American on the United States Customs Court, now called the United States Court of International Trade. The courthouse at One Federal Plaza is named in Watson’s honor.

Watson’s election to the bench created a vacancy to be filled by a special election in February 1964. Like Cordell Cleare’s nomination, the district committee of the Democratic County Committee was sharply divided along club lines. The Carver Club of District Leader J. Raymond Jones supported Constance Baker Motley, who was Thurgood Marshall’s deputy at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. To the surprise of many, however, the committee voted to nominate Noel Ellison, the African-American president of the Riverside Democratic Club.

Controversy ensued when it was disclosed that Ellison, whose main support came from the white members of the committee, had been convicted of running numbers from his dry cleaning store. Democratic County Leader Edward Costikyan intervened when he learned that there were irregularities at the nomination meeting and persuaded Ellison to decline so the committee to fill vacancies could nominate Motley.

Constance Baker Motley already had a distinguished career bringing desegregation cases in the federal courts, including ten arguments before the United States Supreme Court. She became the first African-American woman in the State Senate, but her Senate service was cut short by her election as Manhattan Borough President in 1965, the first woman elected to that post.

Her term as borough president was also short-lived because President Lyndon Johnson appointed her as judge of the United States District Court, the first African-American woman to serve in the federal judiciary. She served in that court, eventually becoming Chief Judge, until her death in 2005.

Basil Paterson was elected to succeed Constance Baker Motley in 1965. As a young lawyer, he became active in the Carver Democratic Club and became a favorite of J. Raymond Jones. Paterson worked hard to protect the interests of Harlem and played a key role in stopping Columbia University from building its gym in Morningside Park.

In 1970, he gave up his Senate seat to run for lieutenant governor on Arthur Goldberg’s ticket; Rockefeller won handily. Ed Koch appointed Paterson as deputy mayor in 1978 and Governor Hugh Carey appointed Paterson as the first African-American secretary of state of New York in 1979.

Sidney von Luther, a Harlem union and civil rights leader won the seat with the support of the Riverside Democratic Club in a three-way primary in 1970 and was reelected in 1972. Senator von Luther proudly identified himself as “a gadfly” and once challenged Senator Martin Knorr of Queens to a duel.

The New York Times quoted von Luther, “there are certain sacred principles that have to be defended and somebody has to appoint themselves as the conscience of that goddam bargaining place.” His Senate colleagues retaliated in the 1974 redistricting by moving a big chunk of Morningside Heights from the district and replacing it with a larger piece of Harlem.

Carl McCall, a business partner of Percy Sutton, was also a familiar figure in reform circles. McCall received support both from the Harlem leadership as well as West Side reformers and cruised to victory in the 1974 primary. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed him to the United States delegation to the United Nations with the rank of ambassador. In 1993 McCall became the first African-American to serve as state comptroller and was re-elected twice. In 2002, McCall received the Democratic nomination for governor, but lost to George Pataki.

Leon Bogues won the special election to replace Carl McCall in February 1980. Bogues had been the chairman of Community Board 7, which covered the West Side, but he was also successful in gathering support from the Harlem leadership. Bogues was re-elected three times and served until his death in 1985.

David Paterson was elected to the seat held by his father following the death of Leon Bogues in 1985 and served until 2006, when Eliot Spitzer tapped Paterson to run for lieutenant governor. David Paterson became governor on March 17, 2008 following Spitzer’s resignation.

Bill Perkins, well known in both the West Side and Harlem parts of the district, was elected in 2006. He had served seven years in the City Council and was a champion of the lead paint laws that addressed that serious housing problem. Perkins was one of the few elected officials to endorse Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential primary and was chairman of Obama’s campaign in New York. Perkins returned to the City Council in 2017.

Brian Benjamin was elected in 2017 to succeed Bill Perkins and was reelected twice. Governor Kathy Hochul appointed him lieutenant governor when she became governor following Andrew Cuomo’s resignation.

***

Douglas A. Kellner is a partner in the law firm Kellner Herlihy Getty & Friedman LLP. He also serves as Co-Chair of the New York State Board of Elections. Kellner chaired the Manhattan Democratic Senate District Committee nominating meetings in 1981 and 1985.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Everything is Connected: New York City’s Climate Crisis Demands a New Way of Thinking

Mayor de Blasio surveys damage from Ida (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

When the long tail of Hurricane Ida brought record rainfall to our region earlier this month, public officials claimed they were blindsided by the damage that resulted. While it’s notoriously difficult to accurately predict rainfall, the devastating societal impacts of the storm were not a surprise to those who follow these issues closely.

An inundated transit system, flooded homes in lower-income neighborhoods, residents trapped in basement apartments. These tragedies were foreseeable, in part, because the city has consistently failed to effectively link its climate adaptation strategy to a social equity and environmental justice strategy.

These recent events are a stark reminder that disasters are not “natural.” They are a function of a system that fails to protect everyone equally, and those in the most economically precarious positions are also the most vulnerable to climate-related hazards. We simply must do more to address the intertwined challenges of climate change and social justice before subsequent stronger storms wreak even more havoc.

Unfortunately, New York City is woefully under-prepared for the climate crisis. Eleven city residents perished as a result of Ida’s floodwaters. It is our civic duty to heed this wake-up call and assure that those lives were not lost in vain.

Complacence, fiscal limitations, and politics are some of the root causes that stymie efforts to adapt in real time to a changing climate. But more than any other factor, we have continually failed to heed nature’s most important lesson, as ecologist Barry Commoner succinctly summarized in his 1971 book Closing the Circle: “Everything,” Commoner explained, “is connected to everything else.”

This single rule, had we ever stopped to consider it, might have helped us avoid the climate quagmire we find ourselves in today. But it can still help us now.

There has been much talk since Ida about how the city needs to more effectively deal with stormwater, refine its emergency alert systems, and protect residents of basement apartments. Yes! Yes! And yes! But we are destined to fail if we view these as standalone problems with unitary solutions. Instead, we need to embrace and harness complexity instead of ignoring what we know to be true: your zip code and your income, more than any other factors, also determine how vulnerable you are to disaster.

As an urban planner, I was trained to think of cities as complex systems, but for a long time those just seemed like hollow academic concepts. Three years ago, I was in the Netherlands trying to better understand how the Dutch have so famously built a thriving, vibrant, livable nation on a marsh that sits mostly below sea level. One afternoon a Dutch engineer grew exasperated by my pestering questions about technical remedies and dressed me down.

“You’re asking the wrong questions,” he told me. “You can always solve a water-related problem with engineering. That’s the easy part, just spend enough money and you can fix anything. But if you don’t use that opportunity to solve a social or economic or environmental sustainability problem at the same time, then you’ve squandered the money the public entrusted to you.”

My friend the engineer, it turns out, perfectly encapsulated everything New York has failed to do in addressing our climate-related challenges. Sure, rain gardens and bioswales have been installed around the city, trees are being planted, and agencies are implementing the City Council’s Unified Stormwater Rule requiring developers to address stormwater risks when they build.

But these piecemeal solutions must also be part of a holistic and comprehensive plan to rethink how we do almost everything in the city, from economic development, housing, and transportation to how we build our parks and schools, what we do with our waste, and where we get our power. A veritable alphabet soup of city agencies will need to rethink what they do and how they do it and collaborate in ways that they have never done before. Most importantly, every decision, no matter how small, will need to be considered through the dual lens of risk mitigation and social justice. This, indeed, is the stated purpose of Mayor de Balsio’s signature OneNYC plan. But despite its pretty pictures, OneNYC, like many of the mayor’s other signature initiatives (looking at you, Vision Zero), has led to few meaningful changes in how the city actually operates.

And those old ways of doing business are anachronisms. In 2019 the city’s Charter Revision Commission failed to advance a proposal to require the city to adopt a comprehensive planning mandate, so the city will continue to pretend that land use and development decisions are wholly separate from decisions about school siting, infrastructure, and transportation. Instead, the city’s antiquated Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) will continue to minimize community input into impactful new real estate developments and fail to connect these projects to any kind of long-term strategic vision for the kind of city we want to see.

Thousands of other U.S. communities have long understood that these issues must be addressed holistically, and this mindset is critical if we want to be more strategic about confronting future climate risks. Council Member Justin Brannan, in fact, introduced legislation back in 2019 to require a citywide waterfront resilience plan. Along with colleagues like Costa Constantinides, Brannan has also been a real leader in pushing the city to recognize and address its vulnerability to climate change. But these are just the first steps, and what we need is not only new and better plans, but a wholesale reimagining of how the city operates, including a true commitment to social and environmental justice.

New York’s climate change adaptation efforts need to heed the lessons that other communities, and even the federal government, have already begun to internalize. A week after taking office, President Biden put forth the Justice40 initiative creating a direct link between the nation’s investments in climate change mitigation and the effort to empower disadvantaged communities.

These efforts are not silver bullets, but they are a start. In New York City, we hear a lot of lofty rhetoric, but the pace of true change feels glacial, while the societal toll from climate change continues to accelerate. The city’s myopic and siloed approach to climate change adaptation results in contentious battles like the one currently playing out over the city’s East Side Coastal Resiliency project, and is why even seemingly simple climate justice solutions like equitably distributing safe bicycling routes seem unattainable.

Massive public investments and politically difficult regulatory decisions will need to be part of New York City’s efforts to address the perils of climate change. Just as importantly we will also need to remake our entire governance apparatus, acknowledging once and for all that risk mitigation and social justice are inextricably linked and foregrounding these intertwined goals in every single decision we make. This evolution won’t be easy, but anything less squanders the painful lessons of Ida and every disaster before it, warnings we ignore at our own peril.

***

Donovan Finn is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Design, Policy and Planning in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University. He is also a proud resident of Jackson Heights, Queens.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Next City Government Must Make New York Safer for Its Oldest Residents

Older New Yorkers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

As we grow older, few things are more essential than feeling safe in our neighborhoods.

For older adults, public safety is more than fighting crime; it’s about maintaining independence and a quality of life and dignity. But currently many New York neighborhoods fall short of creating an age friendly environment where older adults can thrive. There’s work to do, but fortunately our city is experiencing a moment of unprecedented change that represents our best opportunity to make New York a safer, more equitable place to age.

From adopting age-friendly design principles to supporting neighborhood services as we all age, the incoming mayoral administration and City Council will have the opportunity to reimagine a New York City for all ages. That’s why we are proud to support the comprehensive policy agenda released by LiveOn NY and Hunter College’s Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging, which provides fresh and innovative ideas for how the next city government can go beyond policing to make all neighborhoods safe and secure places to age.

For older New Yorkers, public safety includes the community-based services that provide a lifeline to core services such as nutrition and health management support. These human services provided by local non-profits like ours have kept older New Yorkers safe throughout the pandemic, making thousands of vaccination appointments, delivering nutritious meals, and fostering socialization. Unfortunately, for too long, the city has fallen short in making meaningful investments in aging services as well as the human services sector at large. It’s time the city truly supports and fully funds the organizations and workers who continue to show up everyday to support older New Yorkers.

Beyond increasing support for direct services, a safer city also requires significant work to ensure all New Yorkers have a safe place to call home. Today’s tight rental market, old housing stock, and lack of affordable housing conspire to make it difficult for older New Yorkers, particularly those on fixed incomes, to remain housed while making ends meet. We’ll need the next city administration to double down on increasing the production of affordable senior housing with services, as well as support housing programs that can accommodate the changing needs of older residents.

Public safety also means remaining safe from falls, which are the fifth highest cause of death among people age 65 and older. Walkable streets with equitably located resources and accessible transit options, all give older adults the freedom to engage and contribute to the surrounding communities. Fall prevention starts with investing in street lighting and sidewalk maintenance to eliminate tripping hazards like cracks, litter, and snow, and making crossing areas safe for pedestrians. Tragically, older New Yorkers are struck and killed by vehicles at nearly three times the rate of younger people. Let’s commit to create safer areas for New Yorkers by prioritizing walkability and expanding the city’s Vision Zero program.

To build a city for all New Yorkers, our transportation modes must adapt to the needs of people with different levels of physical ability. Currently, only one in four subway stations have key accessibility features. Whether you’re an individual with a mobility limitation or a parent with a stroller, accessibility features such as elevators and ramps are critical to not only preventing falls, but to unlocking all that New York has to offer. It’s time for the state and the city to work together to make our subway system more accessible.

For those that rely on Access-a-Ride, there are also ready-made improvements to be made. Namely, it’s critical for the city to expand its successful e-hail paratransit pilot program across the five boroughs.

Of course, while housing, nutrition, services, and an age-friendly community are key to ensuring New Yorkers can age safely, preventing crime directed towards the older population will remain critical. With the recent attacks on Asian Americans, we see clearly that too often violent crime is perpetrated against older adults and those in marginalized populations in particular. We, as a city, must come together to fight hate and discrimination in all of its forms. From funding local non-profits to build community, to bolstering mental health programs that have proven success, we believe a holistically safe city is possible.

New Yorkers are counting on the next mayoral administration and City Council to make our neighborhoods better and safer places to age. Growing older should build momentum in our lives, rather than slow us down. It’s time to invest in the future of aging in our city. Community-based social services organizations like ours with decades of experience working with older adults stand ready to help the incoming city government make the right investments for our communities.

***

Donna Atmore-Dolly is Executive Director of Allen Community Non-Profit Programs. Anderson Torres, PhD, LCSW-R, is President and CEO of R.A.I.N. TOTAL CARE.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

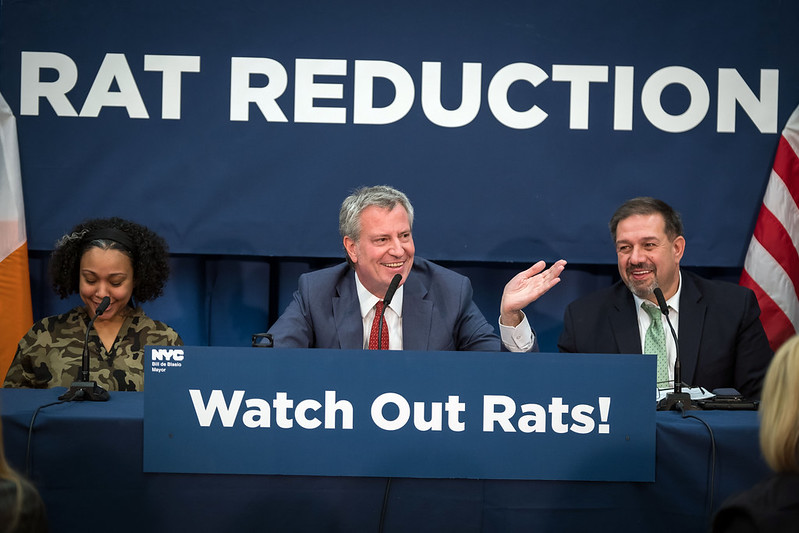

The Next Mayor Can End New York City’s Rat Problem; Here’s How

NYC rats are a problem (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

New York City is inundated with rats! Dirty, dangerous, destructive rats that are also very aggressive. The phrase “Brazen as a New York City rat” has a solid foundation in reality. Mostly we tolerate rats because we think there’s nothing much to be done about them. A few traps, some poison, maybe a new garbage can, but, typically, not much beyond such meager efforts..

It seems that Ida, the recent historic storm, did manage to drown a large number of rats. However, such events are rare enough, maybe even still so in this era of climate change, that we may not be able to depend on them as methods of addressing our city’s rat problem.

Also, mayoral candidate and Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams became infamous for his approach to addressing the rat problem: drowning them in a stew of deadly chemicals. After Adams put his method on full display, some commented on its cruelty. It may be cruel, but it’s also likely ineffective. The rate at which rats reproduce is too fast for drowning them to make much of a dent in their census. What if there’s a more effective way to get rid of all, or almost all, rats in the city? The solution is simple and reasonable, and partly, already exists.

The rats are here for food, and no city feeds rats as often or as well as New York. Three times a week every building in the city places plastic bags full of food waste on the sidewalks, plastic bags that are accessed by rats with ease.

My wife and I -- beginning empty nesters, since our daughter is now away at college -- no longer walk after dinner if it’s a night when garbage bags are put out for collection. Rats darting across the sidewalk and running in and out of bags were more than enough to discourage us. My wife, a social worker in East Harlem who knows several families in public housing, said the rat problem there is much worse than what we see in our Carnegie Hill neighborhood.

Many of the buildings, particularly in public housing high-rises with large numbers of tenants, generate huge quantities of food waste that is easily accessible to rats. As a result, rats are in the garbage areas of the buildings, in the buildings themselves, in individual apartments, and even, horribly, sometimes in children’s beds biting them. It’s that bad!

Yet the solution to this terrible problem is simple: stop feeding the rats.

The city already has in place a pilot program that allows business improvement districts (BIDs) to apply to have their waste and recycling placed in sealed containers before being picked up by sanitation workers. This is a good start, but we need to go much further and fast.

What we should do is pass a city ordinance requiring all residential and commercial buildings to place their food waste on sidewalks in bins that are rat-proof with secure lids. If an ordinance were passed forbidding anyone from putting food waste on the sidewalk for collection, unless it were in a rat-proof bin with a secure lid, that would go a long way toward solving our rat problem.

Achieving the same end, but even better, would be an ordinance mandating composting: a mandate that food waste must be separated out and disposed of in rat-proof bins. The city had a trial composting program for selected buildings, which was suspended due to fallout from COVID-19, but it’s back up. With that program going again, but mandating composting city-wide, the vast majority of food waste from the entire city would be kept away from rats, while at the same time serving as composting material for the program and accomplishing green goals.

New York lags behind other cities in composting food waste, and rat-proof disposal in general. We must catch up.

It will be necessary to give building owners and managers, business owners, and others time to implement rat-proof disposal of their food waste. It may take a few months or more, but if it is mandated and the right city support is there, before long everyone would be doing it, just like almost everyone separates recyclables now. If we separate recyclables, we can also separate food from other household waste.

In addition to prohibiting food waste on the sidewalk, unless in a rat-proof bin, no one can be permitted to keep food waste on their property if it is outside, and not in a rat-proof bin. Since rat-proof bins will be required for putting food waste on the sidewalk, those same bins could be used to store food waste on the premises between collection days. Further, the city would have to make sure that disposal bins in the subways, parks, on street corners, and on other municipal properties are rat-proof. Otherwise, the rats will simply migrate to those food waste bins that are still accessible.

If rats' food supply is suddenly cut off, could this cause a desperate reaction leading to them running helter-skelter across the city looking for food? There will be some reaction for certain. But this plan would not be implemented overnight. Before the entire city was composting all food waste, some months would pass. And likely it would be a year before everyone was in compliance. During that time, the rat population would decrease as less food was available and would continue to decrease as the city moved toward complete compliance.

Further, as rats were being denied food waste, various traditional methods for killing them would become more effective than previously because they’d be hungry enough to eat the poison or go for the food in traps. That is not the case now.

Currently, there’s a lot going on in the city. The Delta strain is on many people’s minds. The city is still struggling with around 10% unemployment. And there’s been an uptick in some types of violent crimes. Maybe, some might say, this isn’t the time to focus on the city’s rat problem. But New York City can and must do many things at once, always. Adopting this program to eliminate our rat problem, and make the city more livable and walkable in the process, wouldn’t by any stretch mean it couldn’t still deal with other issues. Quality of life issues, like the current rat invasion, must be addressed -- just ask those who have to share their homes and beds with rats, or those dissuaded from going for a walk due to the piles of trash on the streets and the rats that enjoy them.

It will take a concerted effort by residents, building owners, managers and supers, businesses, city government, and others to make sure there is virtually no food waste accessible to rats anywhere in New York. It’s a goal we can achieve. In fact, we are on the right track with the city’s composting program as well as the pilot program, mentioned earlier, which allows BIDs to place their waste in sealed containers. The idea behind my proposed ordinance is to expand these efforts to include virtually all food waste in the city. That way, there will be little or no food for rats, and the city’s composting program will be a success: a real twofer. Let’s do it!

***

Michael A. Lewis is a professor of statistics and economics at Hunter College’s Silberman School of Social Work and the CUNY Graduate Center. On Twitter @MichaelALewis10.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Must Act to Protect Transgender Incarcerated People

Lights honoring transgender New Yorkers (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

When I learned that a transgender woman was incarcerated with men on Rikers Island last week, it hit close to home for me. I know from experience what it feels like to be a transgender woman in jail surrounded by men. It's a mix of trauma, fear, and humiliation.

There are far too many stories of transgender women being treated horrendously in America’s prison system that go untold. When we talk about mass incarceration in the United States, transgender people have a unique place in the conversation and must be included in the discourse surrounding decarceration.

Transgender women in particular are notoriously profiled and harrassed, resulting in a disproportionate rate of incarceration in our community. One out of every five transgender women have been incarcerated at some point in their life. For Black transgender women, 47% have experienced incarceration — that’s nearly half of all Black transgender women in America.

While incarcerated, transgender women are nine times more likely to face physical and sexual violence. The humanitarian crisis for incarcerated transgender people didn't begin last week when a group of lawmakers toured Rikers Island — it has existed for centuries in the shadows.

The topic of transgender people in sex-segregated jails is a conversation people usually shy away from. It has only relatively recently been discussed by policy-makers. In 2012, the Federal Bureau of Prisons released guidance that gave instructions to house transgender people in facilities that comport with their gender identity. But in 2018, the policy was effectively reversed by the Trump administration. Currently, transgender people in federal prisons are housed according to their sex assigned at birth. As a result, correction staff regularly place transgender people in solitary confinement as a way to segregate us from the general population.

In New York City, we know what solitary confinement means for transgender people. We remember the tragic death of our sister Layleen Polanco, a personal friend and transgender woman who died at the hands of negligent correction officers at Rikers Island.

Solitary confinement, which is merely an obfuscating term for torture, will never keep transgender incarcerated people safe. Neither will housing transgender people in sex-segregated facilities that don’t match their gender identity. What we need are trans inclusive policies that consider the safety of each individual.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), passed by Congress in 2003, was meant to address the high prevalence of sexual assault among transgender inmates. Although it applies to federal, state, and local prisons and jails, many jails refuse to comply with its provisions, and it is narrowly tailored to address instances of abuse from both correctional staff and fellow incarcerated individuals. Crucially, PREA does not include provisions for trans related medical care nor does it mandate that trans people's identities be respected and affirmed while incarcerated.

Several states, including New York’s tri-state neighbors New Jersey and Connecticut, have taken matters into their own hands by passing laws that implement trans inclusive jail policies. Unfortunately, New York has yet to pass such a law. Which begs the question: why do we afford transgender people in New York protection from discrimination on the basis of gender identity almost everywhere except in our jails?

Countless transgender women incarcerated in county jails across New York share stories of being misgendered by staff and refused hormone treatment and grooming supplies that are consistent with their gender identity. Trans people's inability to live as our true selves can severely impact our mental health. Self mutiliation and suicide attempts are not uncommon for incarcerated transgender people who are refused access to gender affirming care.

To be very clear, the ultimate goal should be to reduce our prison population. But right now New York needs a uniform policy to address the treatment and placement of incarcerated transgender people. We do ourselves a disservice by having a patchwork of policies that vary across each county.

In a perfect world detention facilities would have exclusive transgender housing units. But a major capital investment in new jail facilities is counterintuitive to decarceration and unlikely to happen. Therefore, it should be the norm to place transgender people in facilities that align with their gender identity. For the anti-trans activists who may be against this idea, you should know that there is no evidence to suggest that transgender women are a threat to cisgender women. In fact, it is transgender women who are more at risk than any other demographic in jail. We must also be mindful of the fact that there are transgender women who choose to be in facilites with men. That conversation is valid too, and a trans person's views regarding their personal safety must be prioritized.

We can look to Steuben County for inspiration on how to develop trans inclusive policies in our jails. There, transgender inmates are by default housed according to their gender identity as a result of a recent legal settlement. In addition, Steuben County correctional staff must now respect transgender inmates’ prefered prounouns, provide searches by correctional staff whose gender matches the identity of the inmates, and provide transgender people with trans inclusive care, such as hormone replacement therapy and tolietries consistent with their gender identity. This model can easily be applied across the state.

Thankfully, the answer has already been spelled out for us in the Gender Identity Respect, Dignity, and Safety Act, a bill that would essentially apply the Steuben County model across New York. When lawmakers return to Albany, this bill should be high on their list of priorities to pass. The lives of transgender incarcerated people depend on it.

***

Elisa Crespo is the Executive Director of the New Pride Agenda, a statewide LGBTQ advocacy organization. On Twitter @elisacresponyc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.