As Albany Continues to Abandon Homeless New Yorkers, California Considers New Solutions

Health and housing are tied (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

As roughly 50,000 men, women and children sleep in a New York City homeless shelter each night and the number of people living unsheltered on the streets and subways has increased, the powers that be in Albany bear a large portion of the responsibility for the current state of affairs. It is time that we take a long hard look at what state government has done in this regard instead of putting all the blame on City Hall.

According to the very comprehensive State of the Homeless report published annually by the Coalition for the Homeless, the state government continues, as it has for many years, to receive failing grades on almost every metric. With regard to meeting the needs of unsheltered New Yorkers, New York State received a failing grade on five of the six metrics and a “D-” on the other one. In addition it received similar grades on the operation of the shelter system, housing, and institutional discharge planning.

On this last category, each year since 2015 more than 40% of people released from state prisons to New York City were released directly to shelters. This amounted to an average of about 3,500 a year. As Gotham Gazette recently reported, little is being done to help those leaving prison find stable housing, and so many wind up going directly into the shelter system, with some then leaving for the streets.

The homelessness crisis is being seen more and more as a mental health crisis, which it is in part, and once again New York State bears a heavy responsibility for what we now see. The state psychiatric center system that once served 93,000 New Yorkers has now dwindled to an insufficient 2,330 beds.

Meanwhile, nothing paints a better picture of how state government has abandoned homeless New Yorkers than how the shelters are funded. As the cost of New York City Department of Homeless Services shelters rose by nearly $1.2 billion between fiscal years 2011 and 2021, the city was left to pick up 95% of the increase for single adult shelters and 32% of the increase for family shelters. While the state covered a mere 4% of the additional cost for single adult shelters and 7% for family shelters.

The new state budget is somewhat better but far from acceptable. Lawmakers passed a budget that does little to house homeless New Yorkers, according to exasperated advocates and policymakers. “It’s pretty dreadful,” said Legal Aid Society Supervising Attorney Judith Goldiner.

During protracted negotiations, the governor and legislators axed a proposed Section 8-style rent subsidy for New Yorkers experiencing or at-risk of homelessness. Governor Kathy Hochul and her budget team said it was too expensive.

While New York City and State are facing this monumental task of substantially reducing homelessness they must be equal partners. In California, which is also facing a homelessness crisis, a new approach has emerged.

California has a new plan to get people off the streets and into treatment. CARE (Community Assistance Recovery and Empowerment) Courts connect a person in crisis with a court-ordered Care Plan for up to 12 months, with the possibility to extend for an additional 12 months. The framework provides individuals with a clinically-appropriate, community-based set of services and supports that are culturally- and linguistically-competent. This includes short-term stabilization medications, wellness and recovery supports, and connection to social services, including housing.

CARE Court is not for everyone experiencing homelessness or mental illness; rather it focuses on people with schizophrenia spectrum or other psychotic disorders who lack medical decision-making capacity – before they get arrested and committed to a state hospital.

Although homelessness has many faces in California and New York, among the most tragic is the face of the sickest who suffer from treatable mental health conditions — this proposal aims to connect these individuals to effective treatment and support, mapping a path to long-term recovery.

CARE Court may help thousands on their journey to sustained wellness. Its engagement begins with a petition to the court from a wider range of individuals, including care providers, family members, first responders, or counties, among others. CARE Court may be an appropriate next step after a short-term involuntary hospital hold.

Having served as a Deputy Commissioner in the New York City Department of Homeless Services and as a Vice President for Supportive Housing for a nonprofit, I know it is easy to get caught up handling the day-to-day crises which arise in a system that spends more than $3 billion a year. However, we must set aside time and staff to explore the big picture as California is doing.

***

Robert Mascali is a former Deputy Commissioner at the NYC Department of Homeless Services and a former Vice President for Supportive Housing at Women in Need.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Key Investments New York City Needs to Make in CUNY This Budget

CUNY graduation (photo: CUNY)

Since the start of the pandemic, CUNY students have witnessed trauma every day. They’ve mourned loved ones who died. They’ve struggled with testing and vaccine availability. They’ve borne the stress of the COVID-19 economic crisis, and braved the worst outbreaks as front-line workers to help their families survive.

Unsurprisingly, CUNY’s enrollment declined beginning in March 2020. It’s struggled to rebound, especially at the community colleges where many students come to campus from the neighborhoods hardest hit by COVID-19.

Community college students have always struggled to balance life and a life-changing education. Community colleges around the country face the persistent challenge of retaining students through to graduation. With the increased attention on enrollment this year, now is the time to move toward a solution by investing in the wraparound services that make it possible for CUNY students to return to and stay on campus.

City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams’ recently announced CUNY Reconnect Initiative wisely offers the funding needed to support the services we know work to ensure students remain enrolled and engaged. The initiative would invest $23 million in CUNY and should be supported by the Mayor and full City Council in this year’s budget negotiations.

According to the Center for an Urban Future, there are nearly 700,000 working-age New Yorkers with some college credits but no degree. As a result, the jobs that create a pathway out of poverty and sustain families are often beyond their reach. On average, Americans with college degrees earn 65% more income per week than workers without degrees. CUNY Reconnect would help give working age New Yorkers with some college credits another chance at a great education.

The program emphasizes the need for increased services to help struggling students navigate the college environment. A similar program in Tennessee invested in child care, pre-enrollment counseling, and other services. CUNY is poised to provide such support. But the proposed investment is only a start.

The Speaker’s initial request for $23 million is a laudable beginning but we must go further. CUNY Reconnect can work, while serving existing students, if we make additional investments in the services that are proven to boost graduation and retention rates. One such service is ASAP, the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs Initiative.

ASAP is known as the most successful program at CUNY’s community colleges and modeled around the country in part because it gives students access to a dedicated advisor from enrollment to graduation. Multiple studies show that improved advising increases graduation rates. More funding must be included to increase access to academic advising at CUNY.

Since COVID-19, the increased need for advisors has created an unprecedented backlog. As Academic Advising Director in the Department of Africana Studies at John Jay, I saw the huge increase in numbers of students that needed guidance as we switched back from virtual to in-person learning. And now I see the urgent need for more thorough advisement among students returning to their studies after taking a break during the pandemic. An astonishing 44% of CUNY students are first-generation college students. They depend on advisors to help them navigate a system that can seem byzantine to an outsider. When acclimating to the new and unfamiliar space of college, advisors are their lifeline.

CUNY advisors want to help, but we’re struggling. At a recent union gathering one advisor called the student-to-advisor ratio “mental and emotional murder.” Another noted that “it’s very difficult to do case management because those caseloads are so high… [we are] losing staff members. We are all exhausted.” The current situation is not sustainable and doesn’t give our students what they deserve.

We can do better. CUNY is a public service and a wise investment. In this year’s budget, the City must step up for its people. This year’s New York City budget must expand funding for advising CUNY-wide so that all students can receive the level of high-contact individual attention offered via ASAP. And for good reason: the three-year graduation rate for ASAP students is more than double that of non-ASAP associate degree students at CUNY’s community colleges and it narrows graduation gaps for Black and Hispanic males. A move toward ASAP for All is a $20 million investment that would provide more students with the advisor they deserve.

CUNY students want to graduate, taking their new skills and diploma into the next stage of their lives. The City wants that too. It can’t happen without the wrap-around services students need to navigate college.

***

Rulisa Galloway-Perry is Academic Advising Director and Administrator at John Jay College.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Suburbs Need to Finally Step Up in New York Housing Crisis

Housing in view (photo: Governor's Office)

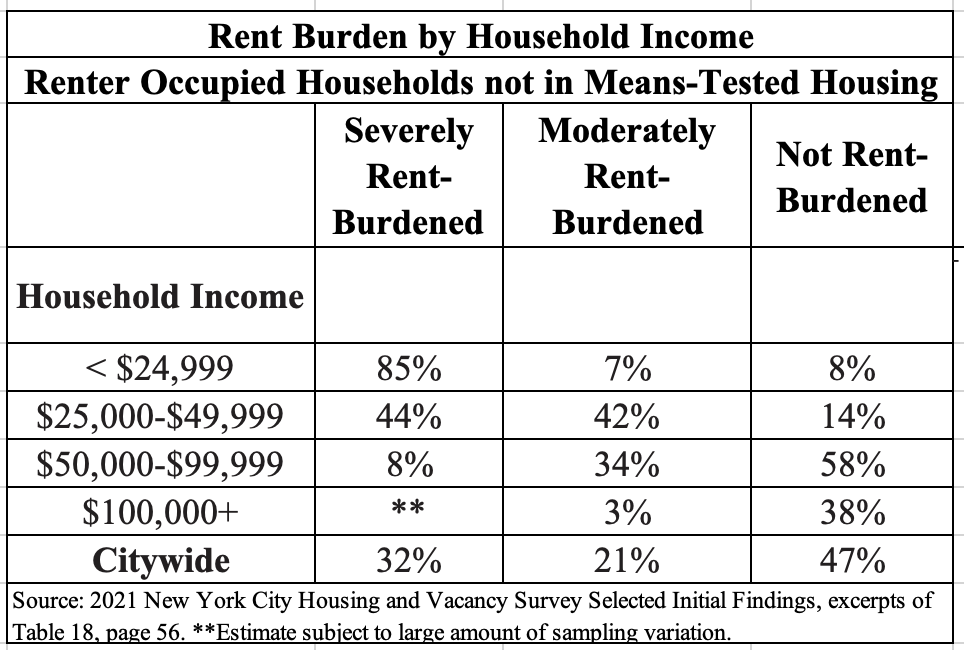

It is easy to focus on New York City proper when thinking about the affordable housing crisis. Initial findings from the city’s triennial Housing and Vacancy Survey, for example, show that 32% of all city renters not living in means-tested housing are severely rent-burdened, meaning paying more than 50% of household income for rent. It’s 85% for households with income of less than $25,000.

But, as New York City Mayor Eric Adams prepares to release his housing plan – building on an outline of proposed citywide zoning amendments he recently presented and other elements his appointees have offered – we cannot continue to ignore the regional dimension to that crisis.

More than 50 years ago, the Regional Plan Association issued a report on housing opportunities in the New York City region, noting in 1969 that there was “growing apartheid” and a “severe limitation” in the suburbs on housing available to members of minority groups. The report further referenced the fact that there was disproportionately little affordable housing in the suburbs and that the growing apartheid system “placed a severe and unfair burden on local governments [most notably New York City] which are left with inordinate costs resulting from poverty.”

Fast-forward to the present. According to 2020 Census data, there are still in Westchester at least 16 towns and villages that have Black populations of less than 3%. Along with the racial segregation, the disproportionate costs borne by New York City as compared with its neighbors in respect to providing both affordable housing and social services remains as well.

Using 2020 five-year American Community Survey data compiled by Social Explorer, I found that only 13.1% of the combined households in Westchester, Nassau, and Suffolk had household income of less than $30,000; by comparison, the percent of New York City households with household income of less than $30,000 was 26.1%.

In other words, the percentage of New York City households defined as “extremely low income” is double that of its suburban counterparts. (At the other end of the spectrum, the percentage of suburban households with household income greater than $150,000 was 34.7%, significantly higher than the 20.1% of New York City households that met that criterion.)

So for all the ideas about what to do about affordability within New York City – including some recent ones of my own – it is important not to forget the critical role that New York’s suburbs are supposed to be playing in providing a fair share of regional affordable housing need.

Despite their acting otherwise, New York City’s suburbs are not beyond the reach of state law (which has long required that each municipality plan for its share of regional housing need). They are not supposed to be beyond the reach of federal law, either. The Fair Housing Act makes exclusionary zoning – like those suburban zoning codes that preclude the building of multiple-family, mixed-income housing – illegal.

Yet these suburbs have, for decades, defied state and federal law and failed to build much housing. From 2010 to 2020, for example, the Regional Plan Association calculates that Nassau and Suffolk Counties had fewer than 10 building permits issued per 1,000 residents, and that Westchester clocked in at only 13.5. Manhattan housing starts per 1,000 residents – inadequate still – were a much higher 30.1.

One notable recent example of the active suburban resistance to building affordable housing is found in the fate of the landmark housing desegregation consent decree that the Anti-Discrimination Center won against Westchester in a case brought under the federal False Claims Act.

The consent decree entered in the case had, according to a brief filed by several fair housing organizations, “provided more opportunity to effect significant structural change in hyper-segregated residential housing patterns than any other legal proceeding in the last 25 years.” Ultimately, though, the decree had to be enforced by the federal government and its monitors, who were unprepared to do so. They snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by failing to have the political will to overcome the county’s resistance.

Even more recently, New York Governor Kathy Hochul proposed early this year what she described as “sweeping plans” to address the housing affordability crisis, including zoning changes to allow accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods and to override local limits on multi-family, transit-oriented development. These zoning initiatives quickly ran into intense suburban opposition, and were dropped from Hochul’s budget proposal.

New York’s Department of City Planning would appear to understand at least on some levels that the city’s housing needs exist within a regional context, but the city’s leadership has never done more than engage in a “pretty, please” approach to seeking regional equity (to be honest, it is not even clear whether city leadership has gone as far as “pretty, please”). The failure of New York City’s suburban neighbors to build their fair share of affordable housing not only hurts their own residents, that failure contributes significantly to New York City’s affordable housing crisis as well. And the failure of the city to press its neighbors to do more has been a grave error.

The city should open its eyes, exert real political will, and be prepared to use all the tools it has available – including state and federal legal tools that I am confident would be successful – to bring affordable-housing “fair share” to the metropolitan region.

***

Craig Gurian is executive director of the Anti-Discrimination Center, based in New York City. On Twitter @antibiaslaw.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Public Health, Public Safety, and the New York City Budget

Mayor Adams at an announcement (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Typically, the scorching hot summer months bring a rise in violence, but there’s much more than temperature at play. Last fall, a Violence Interrupter in Brooklyn shared with us his greatest concerns as we moved to the colder months. He noted that the sunset of extended unemployment benefits would cause more families to be under stress, leading more kids to leave their turbulent home environment in search of solace and kinship in the streets.

It’s not complicated from his perspective.

But this simple and poignant analysis of how poverty leads to violence is rarely reflected in conversations around the city budget.

If we allow public safety to be defined in the context of policing, prosecution, and incarceration, we should not be surprised when we see our jails and courts overwhelmed. Court delays have skyrocketed since the covid pandemic and Rikers Island remains under federal monitoring. Just last month the monitor released another report detailing the mismanagement and violence faced by those detained at Rikers and by the correction officers themselves. We now spend more than half a million dollars annually per client in the Department of Correction – about five times more than in Chicago and Los Angeles – clearly more money for police and jails will not fix this problem.

No Health, No Justice

The Commission on Community Reinvestment and the Closure of Rikers Island released a report last December detailing the root causes of incarceration and the various city agencies empowered to pursue prevention and community-oriented public safety initiatives. From street lights to school nutrition, from youth employment to sanitation, the city’s investments in our residents and our communities pay dividends for decades to come.

Notably, the Mayor is obligated by local law to respond to the recommendations set forth in the report, with oversight from the City Council. The Commission’s Subcommittee on Health laid out a few core principles to frame this conversation. As with our violence interrupter’s story above, the first idea is a simple one: Ensure quality health care is available in the community so the carceral system becomes the last resort for accessing health-care services.

Who could argue with that? Why isn’t this already the case? Regrettably, our reality is far from this ideal.

The Commission report describes health-care deserts, akin to the food deserts we learned about over the past decade. The same communities that are overburdened by the criminal justice system also suffer from worse physical health, mental health, substance use, and social outcomes, mainly due to a lack of access to quality care. Despite the best efforts of the city health department to highlight these disparities, and marshal appropriate resources to respond, this generational inequity persists.

The next section of the report highlights key opportunities to pursue health equity through reforms to the State Medicaid system. The state’s current plan prioritizes individuals and families impacted by the criminal legal system. Most notably, it seeks to activate 30 days of Medicaid coverage prior to release from incarceration, to allow community-based providers to engage clients before they transition back to the community. This will improve the health and stability of some of our most vulnerable residents, and will save taxpayer dollars by preventing emergency room visits and unnecessary hospitalizations.

The state is also planning to roll out hundreds of millions of dollars in opioid settlement funds in the next decade, offering us the chance to build the community substance use treatment and mental health service infrastructure that was promised in the 1970s but never fully materialized. This would mean the ability to access care, same-day, in your own community. No two-month wait list, no travel across the city or county, no wrong door – just quality accessible services including peer supports, safe stabilization spaces, and affordable medications.

These changes will arrive too late for a client we’ll call Stephanie, whose plight is all too common. Stephanie suffers from serious mental illness and when she left prison in 2016 she went to the emergency room for a psychiatric evaluation. Her parole officer threatened to send her back to prison if she did not start taking the $2,000/month prescription medications listed in her release documents. But those documents also listed an incorrect address for Stephanie, preventing her insurance coverage from activating upon her release. With proper insurance coverage, Stephanie could have returned to the same out-patient psychiatric provider she used prior to her incarceration, but she was left without access to this care. The stress of these events further complicated Stephanie’s mental illness, and she was soon admitted to the inpatient psych unit following an incident of self-harm. All because someone listed the wrong address on her paperwork.

We can help future Stephanies and the city can lead the way.

The New York City Council recently held hearings to examine Mayor Adams’ latest budget proposal, hearing from his appointed agency leaders on how they plan to serve the residents of New York City in the year ahead. City budget negotiations are now ongoing before an adopted budget is due by the end of the month.

Let’s take the lead from our sage Violence Interrupter and keep it simple. Protect, support and build up the weakest and most vulnerable among us, and we can all thrive together. That’s the New York Stephanie and the rest of us deserve.

***

Tracie Gardner serves as the Senior Vice President of Policy Advocacy at Legal Action Center. Jeffrey Coots, JD, MPH, directs the From Punishment to Public Health (P2PH) initiative at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Rise in Asian Hate is Taking a Mental Toll on New York’s Asian and Pacific Islander Community

Stop Asian Hate rally (photo: Gerardo Romo/City Council)

As doctors, we have seen the horrific impact of COVID-19, including the adverse effects of our society's socioeconomic divides, social injustices, and widespread racism during this same period. These social ills coupled with the profound health impact the pandemic has had on our nation have intensified the mental health crisis facing Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI). Xenophobia in the United States exploded in the early months of the pandemic and has shown us that what followed the onset of the pandemic was a plague of racial prejudice.

Racism, which results in mental and physical trauma, is a primary cause in the rise of mental health issues across AAPI communities.

In a recent national survey by AAPI Data and Momentive, anti-Asian hate crimes have increased during the pandemic: 1 in 6 Asian American adults reported experiencing a hate crime in 2021, up from 1 in 8 in 2020. Cities across the country are experiencing sprees of hate crimes targeting the AAPI population and other communities of color. According to preliminary analysis, reports of hate crimes skyrocketed in 2021 in more than a dozen of America's largest cities, with a record number of Asian Americans saying they were targets. In New York City, the NYPD reported a 361% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes. And in a recent national poll, 71% of Asian Americans said they felt discriminated against in the U.S. today.

This disturbing increase in hate is taking a significant toll on an already troubled mental and behavioral health care approach in demographics that identify as Asian American and Pacific Islander.

We know that approximately 77% of the AAPI population speaks a language other than English at home. From a medical perspective, telephonic interpreter services are available to patients; however, many Asian patients feel uncomfortable using these services when discussing sensitive issues regarding mental health. Discussing mental health may also be considered culturally taboo within this demographic, making it even more difficult to identify symptoms and treat depression or anxiety. Additionally, roughly two-thirds of U.S. psychologists say their waitlists have gotten longer since the pandemic started. The trouble of finding a therapist or psychiatrist who understands specific AAPI cultural backgrounds adds further barriers to care.

With the rise of Asian hate and the lasting physical and emotional scars of COVID-19, we as medical professionals are charged to help care for the AAPI community in its greatest time of need.

Beyond legal and policy changes, we have the intel, tools, access, and obligation to act now to best serve our patients and communities where they are. Listening to and understanding the community's needs are at the core of what is required to deal with trauma. Physicians need more educational training that highlights overlooked medical issues in the AAPI community, including mental health, early hepatitis screenings, addictions, food insecurities, and foods unique to specific ethnic groups and their relationship to chronic diseases.

For instance, at AdvantageCare Physicians (ACPNY), we are tackling the psychosocial aspects of delivering healthcare services to the AAPI community head-on with cultural competency courses for our healthcare providers. We also formed an AAPI-based employee resource group for our staff to offer in-house insight and support.

Many of our offices are strategically located in neighborhoods with strong cultural identities and diverse needs, including sites in Flushing and Elmhurst, Queens, Crown Heights and East New York, Brooklyn, and Manhattan’s Chinatown. Co-located with centers of our partner, EmblemHealth Neighborhood Care, these locations treat community-specific health care needs, offer translations for written materials, and employ staff who mirror the local communities' language, cultural competency, and backgrounds.

We also work with local elected and public health officials and community leaders to increase awareness of the mental and physical health needs and challenges among AAPI populations.

As New York assesses measures to improve and deploy mental health initiatives, our medical community needs to ensure there is an open dialogue in the process that includes diverse voices. We also need to implement comprehensive plans to enhance clinical practices’ ability to care for all communities' unique behavioral health needs, especially during these difficult times. It is our time and responsibility to unite against racism, and the toll bigotry leaves on our communities.

***

Qian Gu, DO, is ACPNY Flushing North Medical Office Director. Raymond Xu, MD, is ACPNY Astoria Medical Office Director. Seth Resnick is ACPNY Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Department Chair. On Twitter @ACPNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

My Love for New York City

Carlina Rivera with constituents (photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

If you grew up on the Lower East Side during the ‘80s, ‘90s, or 2000s you probably remember Lucky Variety Store. Run by a Chinese family from the neighborhood, Lucky was beloved by local kids, selling backpacks, stickers, costumes, and custom nameplate belt buckles (not to mention throwing stars). When Lucky closed in 2010, a common response was “There goes the neighborhood.”

Many neighborhoods around the city have a version of this story from the last few years: an iconic business closed, years of memories gone with it, and a sinking feeling that the community you call home is changing beneath your feet. As a lifelong Lower East Sider born in Bellevue Hospital and raised on Stanton Street, I can tell you that while my neighborhood has changed, it is still very much there, because – in addition to the businesses and homes that have withstood gentrification – the community is still there. Communities, both on the Lower East Side and across New York City, are what I’ve spent my career working to strengthen and preserve – and I’ll keep doing it as the representative for New York’s new 10th Congressional District.

I spent my childhood with my mom and sister in a Section 8 apartment between Pitt and Ridge. Even as a child, I could see the neglect of our building and our neighborhood. But the families who lived there – most of them Latino or Black or Chinese, along with a smattering of Jewish and Italian residents – were deeply committed to taking care of one other.

Growing up, our building felt like a little village. Everybody knew everybody else. People kept their doors propped open as they cooked, so the hallways smelled amazing – like simmering cabbage, rice, and beans. Neighbors doled out tips on how to be more economical about this or that; if someone noticed a teenager dragging a bag of laundry down the hall, they weren’t shy about making sure the kid knew exactly how to get the wash done properly. To help save money on necessities, people pooled their money for bulk shopping trips. On Easter, my family would head to a neighbor’s to bake a box cake and celebrate together.

That feeling of community extended to life outside the building, in ways big and small.

My mom often didn’t have enough money for a Christmas tree, but that never meant that we didn’t have Christmas. My whole family would go to my great-grandmother’s apartment in the projects in Bushwick for nochebuena — which, if you know about nochebuena, you know it’s a fun night. We’d have one present for everyone, enough food for all of us, and, most importantly, the comfort that came with being together.

As a kid, I made a habit of walking down Rivington to the matzo factory Streit’s, where the bakers would hand out free pieces of fresh matzo through the windows. Like a lot of places, Streit’s is gone now, but so much of the neighborhood remains exactly as it was growing up. I love walking by the same courts where I spent 10 summers playing basketball; Hamilton Fish Park on the east side and Carmine Street Pool on the west, our go to spots for a swim and cool-off in the hot city summers; and Our Lady of Sorrows Church, with a giant Virgin Mary statue that greeted me every time I walked out of my childhood home. My grandparents lived in Brooklyn, so growing up also meant Sunday matinees at Cobble Hill Theater, bowling with our family at Melody Lanes in Sunset Park, and shopping at what was A&S and is now the Macy’s on Fulton in Downtown Brooklyn. After a day spent in Brooklyn with my grandparents I’d come home to the Lower East Side, back to the family and friends that made New York such an amazing place to grow up. I deeply miss the businesses that have closed and the people who have moved away, and I am profoundly grateful that so much of the New York of my childhood is still here today.

I can still pop into Casa Adela on Avenue C, where several generations of the same family have been serving Puerto Rican food for 46 years, with the same salsa music playing and the TV perpetually tuned to either telenovelas or NY1. Casa Adela is also in the midst of a fraught negotiation with its building. The building, which is all affordable housing, is having trouble keeping up with capital costs; meanwhile, the restaurant can’t afford a rent hike. The board wants to keep Casa Adela, a cornerstone of the Lower East Side’s Puerto Rican culture and community, but it also has to cover its expenses.

It’s an example of a type of situation that’s been playing out in the neighborhoods of the 10th congressional district and across the city, in which so many are struggling to survive in an environment that has become less and less hospitable to working people. From Sunset Park to Alphabet City, from Park Slope to the West Village, and from DUMBO to Chinatown, rents are up, local businesses are struggling, and residents aren’t sure what the future holds. As NY-10’s representative in Congress, I’ll prioritize policies that provide real opportunities for those who have served as the backbone of their communities for generations to have a sustainable future in New York.

Taking care of the New York I love, and the New York that raised me, means listening to and fighting for the communities that need help the most. That’s something that became especially clear to me while working on my first community campaign, the development of Essex Crossing in what was known as the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area – a huge swath of land by the Williamsburg Bridge that had been sitting empty for over four decades.

I came to the campaign almost by accident. After several years of working as a camp counselor and in after-school programs, I got laid off, so I had some time on my hands. Marie Christoper – my childhood building’s tenant leader, who was always dragging me and my mom to tenant association meetings, precinct meetings, community board meetings – encouraged me to volunteer at Good Old Lower East Side, a housing organization that’s been around since 1977. Through GOLES, I learned that the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area had once been occupied by tenant buildings where nearly 2,000 families lived, most of them Puerto Rican. Those residents were all displaced in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when the buildings were razed as part of Robert Moses’ “slum clearing” initiative.

I started out by testifying before the community board about the importance of ensuring that the Essex Crossing development would do the right thing by the neighborhood and the people who’d been pushed out. Eventually, I joined the community board – just in time to vote on the first step of the land use process to approve Essex Crossing. While we didn’t get everything we wanted, we did get everything that, by listening to community members, we determined was essential, including a seamless transition and affordable rents for the vendors at the Essex Street Market, a park, and affordable housing for low-income people and seniors.

Perhaps most notably, we secured a right of return for the families who’d lost their homes decades ago; people who could prove they’d lived in the demolished buildings were given priority for subsidized units in Essex Crossing. It wasn’t until I read an article about the returning tenants that I realized that my own father and aunt were among them.

There’s a great Dominican restaurant called El Castillo de Jagua that’s had the same delivery guy for 30 years – he watched me, my sister, and our friends all grow up. But because I was just around the corner, I’d always gotten pick-up. A couple years ago I came down with a cold so bad that I decided to order in. Still, when the delivery guy arrived, I felt embarrassed for not making the short trip myself. I tried to apologize but he cut me off: “I’ll bring you soup any time.”

Sure, this man was just doing his job – but he was also demonstrating the practical sense of care that has been one of the defining elements of my life in New York. It’s something that I’ve always brought to my work representing the 2nd City Council District, and I’ll bring the same thing to Congress.

The reality is that just about every Democrat in the NY-10 race has similar perspectives on major national issues such as codifying Roe v. Wade, increasing gun control, and protecting voting rights — but New Yorkers rightly expect their congressional representatives to do a lot on the local level. I have a comprehensive understanding of what it would mean to really deliver for my district, especially when it comes to the systems that New Yorkers rely on to stay afloat, like the MTA, public hospitals, and housing. The member of congress in charge of bringing back federal transit dollars for the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg Bridges, the Holland and Carey Tunnels, and the transit hubs at Atlantic Terminal and the World Trade Center needs to be someone who uses them regularly, just like the people who live in these neighborhoods.

I grew up in a community where most people weren’t able to imagine much for themselves beyond their next paycheck; I’ve lived that way myself. I want to bring as much money into the district as possible so that we can tackle the systemic inequities that prevent so many New Yorkers and communities from having the stability and resources required to create the lives they deserve.

This district is my home. It’s where I’ve experienced every major milestone in my life, from winning basketball games and celebrating graduations to meeting my husband on the community board (yes, really) and eventually spending one of our first dates walking the Brooklyn Heights promenade.

You’ll see that care reflected in everything I do in Congress. That means identifying with and advocating for the specific needs of the people of the 10th district. It also means being willing to work with people who might not reflect the same makeup of my district or share all of my views, but whose constituents face challenges similar to mine, with the goal of producing results that will benefit NY-10 over the long-term.

A common rallying cry among Latinos is the phrase “pa’lante siempre,” onward always. We say it in times of both progress and struggle, to remind ourselves that it’s our communities that get us through whatever we face — and that no matter what, we face it together.

I’m running for Congress to help build a future that every New Yorker can see themselves in, to continue delivering for the communities that raised me, and to represent this newly drawn district with homegrown pride. New Yorkers are known for our toughness, but everyone in this city knows how much we care for each other, and how much we care about our neighborhoods. My simple promise, one which has served me well in the City Council, is to care fiercely and unapologetically, to put communities and people first, and to protect the future of New York and its neighborhoods. No act of Congress can bring back Lucky Variety Store, but a devoted and determined representative can protect our neighborhoods and residents while creating a future we shape ourselves.

Onward, always. The future of the city we love is ours to build together.

***

Carlina Rivera is a Democratic candidate for Congress in NY-10 and a New York City Council Member for the 2nd Council District. On Twitter @CarlinaRivera.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Lost in Translation: We Need Meaningful Language Access in New York City

Adult literacy programming (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

People from across the world come to New York City to build a new life, bringing with them their customs, cultures, and traditions. Our newest neighbors also bring with them their own languages, contributing to the wonderful diversity of our city, but also presenting a unique set of challenges as families build their new lives.

Take my district in Flushing, which has more than 70,000 “limited English proficiency” Asian New Yorkers, roughly 70% of the total Asian population in the district. A recent report by the Asian American Federation found that two-thirds of Asian seniors need help translating English into one of 12 languages. This doesn’t only present barriers to accessing services, it isolates them in their homes and presents challenges economically, socially, and physically.

Whether you are applying for senior housing or trying to access health care, language barriers can create incredible obstacles for New Yorkers who have limited English proficiency. Before joining the City Council, I worked as an attorney with a nonprofit assisting victims of domestic violence. I saw firsthand how people’s inability to access services in their native language prevented them from getting the often life-saving help they desperately needed.

Frankly, as a city as diverse as ours, we don’t do enough to make sure that immigrants not only have access to translation services, but also to culturally-competent, full-time bilingual staff who can meet the needs of those with limited English proficiency (LEP).

Rather than hiring multilingual staff, many nonprofits and city agencies rely on a service called Language Line or some other outside translation service to assist when a language issue arises. While these outside parties can translate questions and relay answers, they can’t provide context, nor do they always possess the cultural sensitivity to handle issues that may require a deeper understanding of the nuances that exist in a community.

This often leaves LEP New Yorkers searching for someone to help interpret — a child, friend, neighbor, relative. As an immigrant, a child of immigrants, and an attorney in an immigrant community, I’ve seen how stressful it can be for immigrant kids who find themselves acting as interpreters for everything from legal cases to health issues.

Whether it’s an organization providing legal services or social services, nonprofits should be investing more resources to hire native, bilingual speakers as staff. Not only will these staff have linguistic competence, but they will have the institutional knowledge and cultural literacy to handle complex issues with sensitivity.

As I have met with nonprofits to discuss budget designations, I have been struck by the number of them who tell me that they only offer services in one or two other languages, or who believe that Language Line is a replacement for multilingual service providers.

When larger, citywide nonprofits are faced with a language issue, they often rely on smaller, community-based organizations for assistance because those groups do have the language capabilities. In my district, that includes groups like Asian-Americans for Equality, Korean Community Services of Metropolitan New York, Chinese American Planning Council, Garden of Hope, KAFSC, Charles B. Wang Health Center, SACSS, Minkwon, and more.

While larger nonprofits receive a far greater share of funding because of their more established presence in the nonprofit and government worlds, they rely on these smaller organizations to fill gaps in their own services. To provide true equity for our immigrant community, we need to increase funding for the local community-based organizations (CBOs) that are providing linguistic and cultural support to immigrant communities.

Finding, hiring, and employing qualified bilingual staff can be an expensive proposition, and it’s incumbent on city government to help support our community-based nonprofits to meet the needs of constituents. As budget negotiations continue, it’s important to recognize that a lack of multilingual services in an organization essentially means that immigrant New Yorkers have no access to that service. Increasing the amount of money flowing to CBOs in immigrant communities isn’t optional if we want to ensure access to services for all New Yorkers, and the city budget should reflect the diversity of our communities.

In order to increase access to services in a targeted and immediately effective way, New York City should create a new initiative that allocates funds to districts based on the LEP population of that district. This would allow City Council members to allocate more funds to the smaller nonprofits that are providing on-the-ground services in our districts and handling the referrals from larger organizations that lack language capabilities.

In my community and in many others across New York City, the lack of multilingual and culturally-competent services is the equivalent to not providing a service at all. Only when every New Yorker has equitable access to the services and resources they need to succeed will we have a city that truly embraces its heritage as a city of immigrants.

***

City Council Member Sandra Ung represents City Council District 20 in Queens, which includes Flushing, Murray Hill, Mitchell-Linden, Queensboro Hill and Fresh Meadows. On Twitter @CMSandraUng.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Don’t Let Belmont Bonds Become the Next New York Boondoggle

An empty Belmont

The twice-bankrupt New York Racing Association (NYRA) is back at the State Capitol, cup in hand, asking the state to back $450 million in bonds to rebuild Belmont Park’s perfectly suitable and usually empty racetrack. The bonds would be in addition to the millions of dollars the state already provides to the industry through subsidies and tax exemptions. Considering the ongoing financial problems, coupled with diminishing interest and economic development as a result, it would be fiscally irresponsible for the state to back the bonds.

As NYRA seeks this three-decade bonding authority, it remains surprisingly light on the specific details necessary for legislators and taxpayers to evaluate the appropriateness of the spending. This is especially noteworthy following a damaging report authored by Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, a few short weeks ago, highlighting NYRA’s lavish and wasteful spending, inadequate oversight, and violations of the state’s competitive bidding and purchasing rules.

But that’s hardly unique for NYRA. Despite decades of scandals, bankruptcies, and financial mismanagement, the state has continued to prop up the failing association, directing more than $130 million annually in support payments – a portion of which NYRA plans to use to pay back the debt services on the state-backed bonds.

We are the sponsors of legislation (A8468A/S8485) that would take the revenue generated from video lottery terminals at racetracks and invest it in statewide education and economic development. NYRA cites its 2008 franchise agreement (set to expire in 10 years) as the basis for continuing the payments.

However, the state subsidies are in direct conflict with the constitutional mandate requiring that betting on horse-racing “provide a reasonable revenue in support of the government.” The pari-mutuel tax on betting remitted to the state does not even cover the state’s cost to regulate the sport. And, since the inception of the franchise agreement, NYRA has never once paid its franchise fees to the state.

This is a losing bet for the State of New York.

Horse-racing is falling out of public favor due in large part to its history of worker exploitation and animal abuse. A 2021 Marist Poll found that more than 90% of New Yorkers have no intention to attend any racetracks in the future. According to New York records, Belmont’s attendance has fallen by 87% since the late ‘70s. And attendance has been declining even more at 10 of New York’s 11 tracks. Will horse-racing survive long enough to repay New York for the Belmont bonds?

NYRA proposes to dedicate money it receives from video lottery terminals - money that should be going to education - to pay back the debt service on the bonds. Not only does this reroute money the public should be accessing, but it will also create a de facto extension of NYRA’s expiring franchise agreement.

Using state subsidies to pay back state-backed debt does not pass the laugh test.

The public is growing tired of corporate subsidies that lack specific details beyond benefitting the ultra-wealthy, like the sales and use tax exemptions granted by the state for the purchase of race horses. (Assemblymember Rosenthal carried legislation with State Senator Salazar, (A7745/S7260) to eliminate these exemptions.) While corporate bailouts are at a high mark, the public is demanding, and is entitled to, greater transparency.

There should be greater disclosure regarding NYRA’s financials and the public benefit that this bonding authority would provide before the deal is permitted to move forward, if it does. A half-billion dollars could cover the rental arrears for nearly 70,000 NYCHA residents, with some left over. The state should not rush through a half-billion dollars of debt to support a dying industry in an end-of-year “big ugly” legislative deal. The public is entitled to a thorough airing of the facts at public hearings before committing this much money.

Preventing the Belmont bonds legislation is the first step in ending New York State’s long-standing corporate welfare to this failing industry. After 10 years of subsidies, NYRA is no closer to self-sufficiency. Enough is enough. It’s time to cut the cord.

***

State Senator Robert Jackson and Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal represent parts of Manhattan. On Twitter @SenatorRJackson & @LindaBRosenthal.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Albany Can Give New York City More Power to Fix the Housing Crisis

Housing in focus (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

State lawmakers clearly understand that New York faces an emergency-level housing crisis and have acted accordingly: adopting a five-year housing plan to invest $25 billion in affordable and supportive housing across the state. But the job is not over, there are several important housing bills under consideration that would help New York City fight the housing crisis.

In the final days of the state legislative session, Albany has a chance to help the city help itself by giving it new authority and without spending another dime this year.

Perhaps the most pressing housing issue in New York City is the living conditions at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). NYCHA public housing needs $40 billion in repairs and while there was optimism last summer that the president’s Build Back Better bill would provide needed funding, there is now little hope of the federal government coming to the rescue.

There are more than 535,000 New York residents living in 177,500 NYCHA apartments, and we cannot afford to lose a single unit without exacerbating our grave housing crisis. Fortunately, there is legislation in Albany that would give NYCHA new tools to raise capital, while leaving public housing in the hands of the public, where it belongs.

The proposed legislation would create a public trust to raise the additional funding and allow procurement capabilities that NYCHA doesn’t have for contracting repairs. Most importantly, the new plan puts tenants in the driver’s seat. The current bill allows tenants to vote on whether their properties are involved with the preservation trust. The unacceptable conditions residents live with every day should give extra resolve for lawmakers to approve the creation of a Public Housing Preservation Trust that unlocks new financing for NYCHA while preserving tenant protection and public control.

At the same time, the state can also give the city tools to improve, preserve, or convert affordable housing in the private market. There are several ways it can do so.

First, the state must allow New York City to modernize its housing programs for the 21st century by updating outdated lending authority. The proposed Affordability Plus legislation would allow the city to align their housing programs with market lending term periods and provide more flexibility on loan amounts and income requirements. This will help streamline many of the affordable housing finance programs. The legislation would also help to make affordable homeownership and community land trusts for housing possible. Currently, state law prevents the city from lending to the types of community ownership projects that many support in the city; outside of city-owned land.

The city can also add more affordable housing through legal and safe conversions. We now know that a good portion of the hotels that shuttered during the COVID-19 crisis are occupied by tourists again, but many are still in financial trouble. These properties can and should be converted into affordable units, which can be done far more quickly than building new construction and provide relief in a matter of months. But the conversion process is over-regulated and therefore cost-prohibitive. The state must amend the law to allow hotel conversions while retaining their existing Certificates of Occupancy.

Lastly, the state can help New York City take action on legalizing basements to improve safety and compliance in each borough. State legislative action will allow the city to fast-track solutions that have been stalled due to the complexities of the building and zoning codes. Following the devastating eleven drownings in basements during Hurricane Ida, there is renewed urgency to legalize basements that can be made safe and to enforce dangerous noncompliance.

These are common-sense solutions to complex problems, and they are uncontroversial: housing leaders in and out of City Hall agree that they would make a difference and are asking Albany to implement them. That means the only impediment is advancing these bills in Albany in the final days of legislative session. During a crisis of this magnitude, we need all hands on deck to solve a housing crisis and we have no time to waste.

***

Rachel Fee is Executive Director of the New York Housing Conference. On Twitter @RachelFee4NY & @TheNYHC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Needs to Ban Hybrid Voting Machines Before They Make Our Elections Worse

The ExpressVote XL 'hybrid' (photo: ExpressVote XL)

New York needs to ban hybrid voting machines before they start being used, and the opportunity is here.

Using these hybrid machines — where voters both mark and cast their ballot — is not good for voters, will not help election administration, and run the risk that voters will lose faith that their votes are counted accurately.

There is a bill before the State Legislature (SS309B/A1115C) that needs to pass now — there is no time to lose, our current machines are already overdue for replacement and the NYCBOE (as well as other county BOEs throughout the state) are wanting to replace them with these hybrid machines. And the 2022 legislative session in Albany is scheduled to end this week.

Yes, we need to replace the ballot scanners we currently use. They were purchased in 2010 and are long past their reasonable lifespan. But we do not need to replace them with machines that will make the voting experience and elections worse, especially in New York City. At a time when our democracy feels very fragile, we cannot and should not spend tens of millions of dollars on machines that are less secure, will create longer lines for voters, and where voters will not feel confident their ballot is counted properly.

We need to prioritize the voter. Taxpayer funds should be spent on election equipment that makes elections better, not worse.

Hybrid voting machines like the ones being considered in New York are direct-recording ballot-marking devices and tabulators. This means voters never touch their ballots themselves. The voter uses a touchscreen to make their choices and the machine records their votes. The manufacturer says voters will have an opportunity to “review” their selections, but in reality, voters will look at a receipt-like display on the machine’s screen. This display will show the names of candidates the voter selected, but the machine bases its tabulation on the barcode printed next to the name. New Yorkers read hundreds of languages, but “barcode” isn’t one of them. This is a smoke and mirrors approach to a voter-verified paper audit trail, the gold standard in elections.

One of the biggest security flaws in hybrid voting machines is not hacking, but that we might not have the ability to determine voter intent to do a manual audit, which is required by state election law. The “ballots” from the hybrid machines are printed on thermal paper, which is not easily preserved. This type of paper needs to be preserved in ways that our current paper ballots are not - and it is still unclear how or if this can be done.

We don’t know if a race is within the manual recount margin until at least two weeks after Election Day, as absentee ballots, as long as they are postmarked by Election Day and received within 7 days after (plus takes a few days to verify the postmark and signature and we now have a process to allow voters to add a missing signature. It’s unclear if the hybrid machine “ballots” will be legible to be recounted after this amount of time.

Additionally, multiple people have to touch the ballot many times during the manual audit - to pick it up, to show it to observers, and put it back. We can’t be sure the thermal paper -- the only kind used by the machines under consideration by the New York City Board of Elections and other election boards, the ES&S ExpressVote XL -- can handle this. We need ballots that can stand up to repeated recounting so voters are assured the machines work as intended. The alternative creates a potential nightmare for democracy and a crushing blow to trust in our elections.

New York has complicated elections and bottlenecks do occur. Yes, a non-working scanner slows down the process, but non-working hybrid machines would grind the voting process to a complete halt. With these hybrid machines, voters will have to wait for an available machine to both complete their ballot and cast it. Bottlenecks also occur when 1) machines go down and require a technician to fix; 2) voters need a lot of time to vote; 3) it’s a peak voting time; and 4) there are elections with highly-contested races. Bottlenecks make time-starved voters especially frustrated and more likely to leave and never cast their vote at all. The hybrid voting machines could exacerbate these bottlenecks at each point.

Then there is the capacity of the hybrid voting machines, which will cause further delays for voters in high turnout elections. Our current ballot bins that receive the scanned ballots need to be swapped out every 2,500 ballot pages, a process that takes about 10 minutes (and the scanners rarely - if ever - get to that amount of ballots). In contrast, hybrid voting machines require the printer hopper to be replaced after every 250 votes. While the cartridge is being replaced, the machine is out of service, causing yet more delays to voters. Why would we want machines that are designed to go out of service at the exact time that they are being used the most?

The manufacturer’s response is to point to Philadelphia, which uses similar hybrid voting machines. But there’s no comparison when you look at the numbers. Philadelphia has 1.1 million registered voters across 1,703 divisions (the equivalent of New York City election districts). In the 2020 general election, about 749,000 people voted, about 50% of whom voted via Pennsylvania’s absentee/mail-in/early voting process, so only about 375,000 voters actually used the hybrid voting machines. Each machine on average serviced about 125 voters. Virtually no machine serviced more than 250 voters, which is the point at which the paper hopper would need to be swapped by an on-call technician, per Philadelphia procedure.

By contrast, Brooklyn alone has about 1.5 million registered voters, of whom about 920,000 voted in the 2020 general election on the scanners. Each of the current type of scanners served, on average, under 250 voters, but this is an average, so many of Brooklyn’s poll sites had scanners with MORE than 250 voters per machine. Remember those long lines during early voting? Wait times would have been even longer had hybrid voting machines been in use. The Philadelphia experience is not at all comparable to the NYC experience.

Hybrid voting machines are bad for voters, bad for the voting process itself, and bad for increasing trust in our elections. New York must ban these machines and actually work on making voting easier for all eligible voters.

***

Judith Hertzberg, Jan Combopiano, Julie Kerr, and Erica Cohen are co-founders of Brooklyn Voters Alliance, an all-volunteer, non-partisan organization that works to protect and expand voting rights in New York State. On Twitter @BKVoters.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.