Permanent PATH Station

by Joshua Brustein

January 23, 2004

|

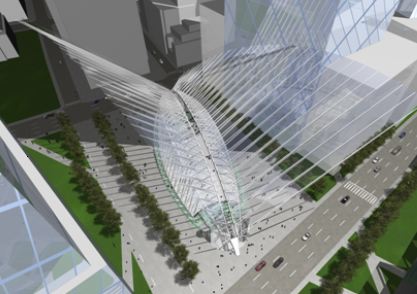

View from above

Night view

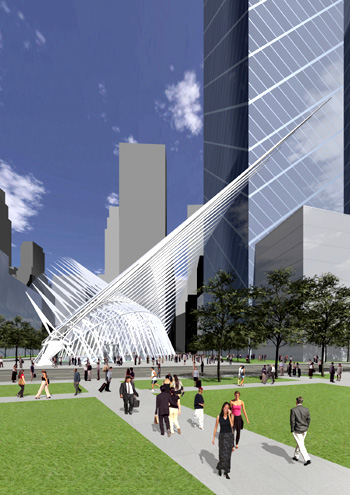

View from the South

|

On an oversized sketchpad, famed Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava

drew a sketch of pair of children's hands releasing a bird into the

air. This image, he told the audience who had gathered to see him at

the Winter Garden on January 22, was the root of his plan for a

permanent train station at Ground Zero. He then grabbed another marker

and, over his previous drawing, drew the design that many are already

referring to as downtown's Grand Central – an oval of glass and steel

with wings rising from its spine.

This, in broad strokes, was the third major piece of architecture for

Ground Zero to be presented to the public in the last two months, and

part of yet another extravagant "unveiling." The previous ceremonies,

for the freedom tower

and the memorial,

have inspired intense

anticipation, attracted large crowds, and received mixed reviews. While

the presentation for Ground Zero's train station drew fewer people and

less emotion, those in attendance seemed uniformly dazzled.

Construction for the station, for the Port Authority Trans Hudson or

PATH train, is expected to begin next year. It will begin carrying

riders in 2006, and will be completed by 2009. The cost of the station is about

$2 billion, much of that coming from federal money earmarked for Lower

Manhattan transportation after 9/11.

Calatrava said that the main intention of his design was to "use light

as a construction material." The steel, concrete and glass pavilion at

ground level is essentially a skylight for the station's lower levels,

allowing daylight to travel 60 feet straight down to the tracks below.

By creating covered areas around the station, the block-long, 150

foot-tall wings serve to protect visitors from wind and rain. On more

favorable days, the roof retracts, a sort of train-station-skydome that

opens the station to fresh air.

The large wings are the station's most striking visual feature.

But Calatrava intends the roof of the PATH station to be more than a

grand architectural gesture; it serves practical purposes as well. A

building that relies on the sun for much of its light needs to use less

energy from other sources, he said, and a retractable roof offers

safety in the case of fire.

Calatrava is best known for applying this kind of expressive

architecture to bridges and train stations. When the Port Authority

chose Calatrava, along with architectural-engineering firms DMJM +

Harris and STV Group, Inc., to build the station at Ground Zero in July

2003, Herbert Muschamp of the New York Times proclaimed that Calatrava

was "the world’s greatest living poet of transportation

architecture…Long before the word 'infrastructure' had entered the

lexicon of contemporary architecture, Mr. Calatrava had taken this

genre of design to the level of genius."

In contrast to the Memorial and the Freedom Tower, which have departed

in many ways from Daniel Libeskind’s master plan for the site,

Calatrava’s station uses one of the major elements of the plan as a

starting point for its own design. The wings that run the length of

station frame the "wedge of light," a public space envisioned by Libeskind that

is designed to have no shadows on September 11 of each year from 8:46 a.m.,

when the first tower collapsed,

to 10:28 a.m., when the second fell, accenting

further this element of the original master.

"This is how architecture develops out of master plan," said Mark

Ginsberg, president of the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

"The master plan had this strong idea of the wedge of

light. Calatrava took that and used it to in certain ways generate his

building, making something that is a wonderful sculptural element and

an icon in the city and for the site, but also by in some ways

modifying the ideas of the master plan strengthening [it]."

The station will eventually connect to the Fulton Street subway

station, which is currently being renovated by the Metropolitan Transit

Authority in a plan that will be presented to the public this spring.

In all, 14 subway lines will be accessible from the station, which will

also connect to ferry service and airport rails. It will also include

pedestrian access to the World Financial Center. Many hope that it will

serve as the centerpiece for a regional system of transportation that

will rejuvenate downtown Manhattan.

"Much as the rehabilitation of Grand Central Terminal has sparked the

revitalization of midtown, the restoration and enhancement of Lower

Manhattan's transportation system will accelerate the economic recovery

of the nation's third largest business district," said Port Authority

vice chairman Charles Gargano at the unveiling.

Calatrava's building was being referred to as the Grand Central's

downtown equivalent long before his sketches were made public. Now

Calatrava himself has reaffirmed this hope. He referred to the midtown

station as the "most beautiful public hall of any station in the

world," adding that it was probably the "deepest inspiration" for his

design.

Interior, with roof closed (left) and open (right)

|