What Comes First in City's Reset on Food Waste? Skip the Truck

Compost collection (photo: New York City Department of Sanitation)

Last week was Food Waste Action Week in the United Kingdom and across Canada.

The focus? Reducing and preventing food waste, with a variety of programs supporting smarter purchasing and cooking, with the goal of attacking what nearly every household generates too much of.

By the (Canadian) numbers: 63% of the food households throw away is considered avoidable, meaning it could have been eaten.

In the United States, that amounts to millions of tons and billions of dollars wasted, with huge greenhouse gas emission and water-wasting impacts.

In New York City, the debate over managing our mountains of food waste is focused on how to put it in special containers, collect it in trucks, drive it for miles and process it into compost (which is the product, not the raw material), and deal with the inevitable contamination.

But the debate largely overlooks food waste prevention or reduction and recovery of edible food; after all, food’s intended purpose is feeding people, giving us the energy to do great things.

Since the early 1990s, the city has struggled with asking New Yorkers to separate their food scraps for weekly collection in a truck, or to take it to a drop-off site. While these efforts have their advocates and some success, the numbers don’t lie: these voluntary programs have failed to achieve critical mass in a city of 8.8 million people. Both the number of households and actual tons diverted from disposal are so far low.

The unfortunate consequence? Truck-based collection becomes super-expensive per ton carried – a big truck with little payload, making little impact on our waste management costs or the environmental impact.

As a consequence, Mayor Adams’ first budget plan proposes to suspend expansion of the restarted curbside collection effort beyond the current seven community districts. Other community-based and low-cost approaches – drop-off sites at green markets, for example – will continue to be funded so that options for dedicated residents will be available.

This ‘time out’ for course-correction has its precedents; even the city’s now-standard recycling system went through similar start-stop-start cycles during its first two decades, confusing the public and delaying the benefits of the complete, citywide program.

Now the question is what will be done during this time out to build back better, to borrow a phrase. Have we learned any lessons?

Some suggest the answer is to mandate separate collection and management of food scraps – adding a fourth container alongside those for paper and cardboard; metal, glass and plastic containers; and non-recyclable trash.

Most agree that the city needs a thoughtful comprehensive plan for dealing with all types of organics – food scraps, yard waste, Christmas trees, and even biosolids from wastewater resource plants. All options should be on the table, including promoting donation of edible food, more composting, and anaerobic digestion.

But the first step can be done even sooner: Mayor Adams and City Council leaders could launch this year a citywide campaign focused on preventing and reducing food waste from all sectors — households, schools, and commercial businesses alike. This campaign would raise awareness about the importance of preventing and reducing food waste and raise a shared sense of purpose and participation.

Fortunately, great models are in action – in London and Vancouver, among other places. Philadelphia is about to launch “Eat Away at Food Waste.” The results are astonishing – reducing avoidable food waste by as much as 20% in a diverse array of communities.

Everyone can help. Prevention programs also attract partners in ways that trucks don’t – food markets, food pantries, and other food-related businesses all share an interest in promoting prevention. All neighborhoods can participate and businesses, too, without worrying about truck routes, inclement weather, and other variables.

And it’s healthier – for the planet, for our pocketbooks, and our personal health. Making less food waste is a great way to save money, save water, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, among other benefits.

Even better: reducing and preventing food waste takes edible food away from rats.

Putting the reduction and prevention of wasted food at the top of the city’s efforts would be the best possible use of this ‘time out.’

***

Brendan Sexton is a former Commissioner of the New York City Department of Sanitation and former Chair of the Manhattan Solid Waste Advisory Board. Jacquelyn Ottman is a former Chair of the Manhattan Solid Waste Advisory Board.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Two Housing Budget Items the City Council Should Push the Adams Administration On

Housing in the Bronx (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office)

When the New York City Council’s Committee on Housing and Buildings hosts its first preliminary budget hearing on Monday morning, it will be held against the backdrop of severe economic uncertainty for many New Yorkers. Inflation rose nearly 8% last month, driven by soaring food and energy costs, putting immense pressure on low- and middle-income families even as the job market remains robust for workers. Rents are also on the rise, in some cases increasing as much as 33% between January 2021 and 2022.

In New York, this uncertainty is also driven by a familiar cause: a rapidly worsening affordable housing crisis that has left households strapped for cash for decades. The statistics are familiar, but that does not make them any less harrowing or in need of attention.

About half of New York renters spend a third of their income on rent, leaving them especially vulnerable to inflation and economic shock. Rent-burdened very-low-income households have just $560 in residual monthly income remaining after rent, on average. These are the families most acutely feeling the squeeze at the supermarket. Many still have unpaid rent arrears accumulated due to lost work or wages during the pandemic, placing them in a financial chokehold: New York’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program needs $1.6 billion to aid renters. It is a brewing eviction crisis beneath the economic crisis.

Put simply, we have no hope of a real recovery that works for everyone without first addressing the city’s housing emergency. The City Council will have a big role to play – and it should lead by example as we await the details of Mayor Adams’ first comprehensive, long-term housing plan. Fortunately, there is a clear plan of action.

First, City Council members should apply pressure on Mayor Adams to live up to his campaign promises. On the campaign trail, Mayor Adams told the United for Housing coalition that he would double city spending on housing to $4 billion. He knew it was a smart, fiscally responsible way to improve lives and create jobs. In his preliminary budget, however, he did not add capital to the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) at all – it was unchanged from Mayor de Blasio’s final budget.

This is disappointing, but it is not the final word. Pressure from the Council would go a long way toward making this vision a reality and providing relief to constituents who badly need more housing opportunities, better living conditions, and rental assistance to make ends meet. It would also help improve conditions at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). That pressure campaign should begin tomorrow.

Second, the Council should ensure that the agencies in charge of housing policy are staffed and resourced in such a way that will allow them to be efficient and maximally productive. Recent New York Housing Conference analysis shows that the city is badly missing the mark in this area, and it is every day New Yorkers who are paying the price due to the inefficiencies this causes.

Consider that the Human Resource Administration (HRA) is more than 1,600 workers short of its budget appropriation, HPD is more than 300 short, and the Department of Homeless Services is more than 100 short. Making matters worse: many of those vacancies are in critical areas. Staffing shortages are delaying much-needed services from reaching New Yorkers and preventing much-needed affordable housing projects from coming online. If staff vacancies continue to go unfilled, we will see a decrease in affordable housing production at a time when it is needed more than ever.

The Council should push the administration for a plan to quickly staff up the agencies, which may mean offering flexibility for provisional hires; increasing the autonomy of agencies to get staff on board without redundant reviews from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and being more competitive with private-sector salaries by allowing managers to offer salaries within a pay scale not just the bottom rung of it. In this tight labor market, the government cannot compete without changing hiring rules.

The shortages make it harder to be efficient, too. The Citizens Housing and Planning Council (CHPC), for example, found that it takes on average 430 days from when residents begin applying to an affordable housing lottery for all the units to be filled. The Supportive Housing Network of New York (SHNNY) estimates there are 2,500 supportive apartments vacant while 8,000 eligible applicants in need are waiting. Addressing these shortages – as well as other bureaucratic inefficiencies – will help get New Yorkers in homes faster.

This is only a small sampling of what is needed to address the housing emergency. More must be done to combat homelessness and to fix the embarrassing conditions at NYCHA. But by fighting for these two common-sense solutions, the City Council can step up and support New York’s renters and lay the groundwork for a better, more equitable city overall.

***

Rachel Fee is Executive Director of the New York Housing Conference. On Twitter @RachelFee4NY & @TheNYHC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

After Twin Parks: We Need an NYC Office of Fire Door Safety

FDNY on the scene in the Bronx (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Walking up four floors in a friend’s apartment building the other day I noticed something you might not: on almost every floor, the door to the stairwell was open. Someone had just casually propped them open, maybe to make going in and out easier because the doors are so heavy. I also notice some of the apartment doors that are just simply open, not propped up, when they should be self-closing based on a recent law passed by the City Council mandated that building owners across the New York City ensure all apartment doors are self-closing if they provide access to stairwells.

Noticing something as seemingly innocuous as this is a funny habit I picked up because of my work, and it’s especially relevant these days because open doors like these contributed to a recent tragedy: the fire at the Twin Parks housing complex in the Bronx earlier this year that left 19 dead and stunned the city. Yes, the innocent act of propping open a stairwell or apartment door can be deadly, as can malfunctioning doors. While the main cause of the fire appeared to be an electric space heater, open doors allowed and encouraged smoke to spread upward. It’s a tragic but valuable lesson and we must ensure that all apartment and stairwell doors work as required and that they aren’t left propped open.

Fire doors and self-closing apartment doors are designed to help contain smoke, since the main cause of fire death is often smoke inhalation and not the actual flames. That’s what happened at Twin Parks – in addition to the apartment door where the fire originated, at least one stairwell fire door was propped open, and smoke billowed throughout the building. Properly functioning fire doors can minimize or eliminate devastating tragedies like this, and residents of New York City need to be educated about them and the seemingly mundane but absolutely crucial purpose they serve.

But that’s not all. Education campaigns only go so far – fire doors will malfunction if they are not assembled properly or maintained. They need to be inspected by trained personnel; inspections that should be mandatory and enforced by the city.

There’s the rub beyond city law.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has more than 300 standards to minimize the impacts of a fire. NFPA Federal Code 80 states that “fire door assemblies shall be inspected and tested not less than annually and a written record of the installation shall be signed and kept for inspection by the authority having jurisdiction.”

The problem -- not just in New York City, but in most jurisdictions -- is that this code is not strictly enforced. In other words, thousands of buildings around New York City most likely have not had their fire doors inspected, not annually nor even in the last five years. We have no way of knowing whether fire doors have working smoke seals or correct latching to ensure they automatically close in case of a fire. The fire department certainly doesn’t have the capacity to inspect them; firefighters have more than enough on their hands responding to emergencies.

This is why New York City needs an Office of Fire Door Assembly, Safety and Protection within city government. There is precedent for this.

You have probably noticed that elevators in New York City have the date and signature of the inspector who last inspected the elevator visible to the riders. Property owners are already responsible for regular elevator inspections by licensed technicians. These policies were put in place and strengthened to make elevators safer after a series of tragic incidents. Something similar noting when fire doors were last inspected should be clearly visible close to the main entrance of New York City buildings.

This doesn’t have to be a heavy lift. Denver, Colorado, which experienced significant population growth in recent years, strictly enforces fire door inspections in all of its new high-rises. The State of California requires fire door inspections in its public schools. They are certified by the California State Fire Marshal.

Only health care facilities in New York City now receive such inspections, which are federally mandated, and rightfully so.

We need a three-pronged approach.

Educate building operators, landlords, and tenants on why a fire door is there in the first place, and that it must always be closed when someone is not passing through it.

Ensure that fire doors are inspected by trained personnel.

Require compliance.

To do all this, we need a dedicated office within city government and a revenue stream to meet the standards of NFPA 80. Otherwise, our city is not taking all the necessary precautions to ensure that the tragedy of Twin Parks is never repeated.

***

Jacob Wexler, FDAI, is an accredited consultant in the door and hardware industry specializing in fire door assemblies and acoustical door assemblies.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

High Hopes for New Era of MTA Transparency

Subway riders (photo: Marc A. Hermann / MTA)

In October 2021, Governor Kathy Hochul signed the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Open Data Act, sponsored by Senator Leroy Comrie and Assemblymember Robert Carroll. Hochul said the law will require MTA data to be “properly available for constituents to read and utilize. New Yorkers should be informed about the work the government does for them every day, but we have to make it easier for them to get that information."

The new MTA law is the first open data law passed by New York State and was championed by Reinvent Albany with the support of more than a dozen advocacy organizations. The law is now being implemented by the MTA, a state authority that runs the New York City subways and buses as well as the commuter railroads.

The MTA currently has a $18.5 billion annual operating budget, and is the largest public transit authority in the United States. Before COVID-19 hit, it served 5.5 million daily riders on the subways alone, and millions more on the buses and railroads. It is currently undertaking the largest capital plan in its history, with $55 billion in planned spending on infrastructure. Given the MTA's importance to the region's economy, the authority's operations and spending are of great importance to policymakers, riders, and all New Yorkers. One way to pull back the curtain on how the MTA is doing its job is through greater transparency.

Efforts to increase transparency at the MTA are not new. A decade ago, at the urging of advocates and riders, the MTA began releasing real-time service data as open data to the public via third-party apps like Google. The MTA has since created numerous performance and capital program dashboards, but there is much work to do to consolidate the underlying, raw data and ensure it is updated automatically on the state’s open data portal. The state’s portal provides tabular public data – essentially spreadsheets, mapping data, and other types of data – from the various state agencies and authorities in one place, allowing journalists, advocates, and the broader public easy access to state government data.

This week is Open Data Week, and next week is Sunshine Week. Fortunately, this time around we are optimistic about the future of MTA open data because of the new state law and what the government and the public have learned during the COVID-19 pandemic about the value of transparency.

Now, the MTA can let the open data sun shine on three high-profile and timely concerns: daily ridership numbers and projections for the future as the MTA emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic; the upcoming congestion pricing environmental assessment; and the release of its 20-year needs assessment in 2023.

What Does the MTA Open Data Law Require?

The MTA Open Data Law codifies for the MTA the requirements of Governor Cuomo’s Executive Order 95 of 2013, the state’s Open Data EO that established data.ny.gov. The bill defines what is publishable data and requires the MTA to designate a data coordinator to oversee agency’s compliance.

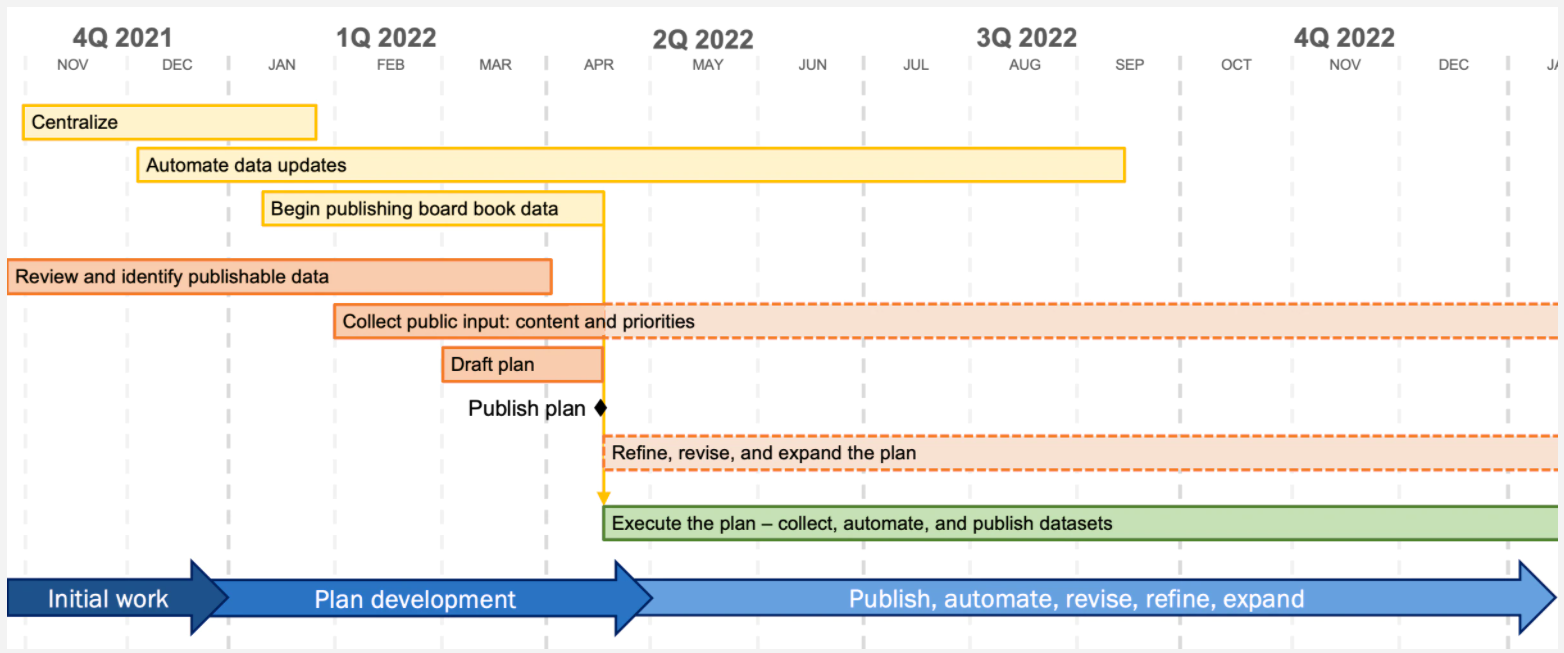

Under the law, within 180 days – in April 2022 – the MTA must create a catalog of public datasets and a schedule for release of this data within three years. The schedule and catalog will be provided to the Legislature and the public.

What Has the MTA Done So Far?

In October 2021, the same time that the MTA Open Data Law was signed, Governor Hochul asked each agency to produce a Transparency Plan regarding their efforts to increase transparency and release more information to the public, including as open data. The MTA’s transparency plan includes a detailed description of how they will implement the MTA Open Data Law, including deadlines for publishing more data on the state’s open data portal.

The transparency plan also notes that the MTA can reduce its Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) load and costs of producing records by uploading more data to the open data portal. The MTA recently offloaded requests for police incident reports from their FOIL requests into a separate electronic portal. This action was in part spurred by Reinvent Albany’s finding in our Open MTA report that two-thirds, or nearly 6,000, of the MTA’s 9,000 annual FOIL requests were for police incident reports.

Sarah Meyer, the MTA Chief Customer Officer who first came on with Andy Byford at New York City Transit, has been designated as the data coordinator, and will lead the agency’s effort.

The MTA has grown the number of its datasets on the open data portal from 76 to 100 as of March 9, 2022, and intends to publish a number of other datasets in the short term. The MTA’s plans are also detailed on a new website that outlines its efforts to comply with the law, which includes the following timeline:

This timeline importantly includes that the MTA will “automate data updates” – this means that data will not need to be manually uploaded each time there is an update. This is crucial for the sustainability of the MTA’s open data and transparency efforts because automating data release will reduce staff time and ensure it is the most useful to the public.

Opportunities for New Open Data Releases

The MTA’s transparency plan has prioritized getting MTA data that is already published in PDFs up on the open data portal, including data from the MTA Board Books and financial plans, which is an excellent first step. However, there is a wealth of data – including raw data – that is not currently published as open data that is of great interest to the public.

Additionally, when the MTA announces major new initiatives or releases new reports, these are important opportunities for the agency to think ahead about what data should be released as open data.

We recommend that the MTA specifically integrate open data into three upcoming or timely initiatives:

1. Ridership Projections

The MTA’s daily ridership numbers are important markers for policymakers and New York City boosters given the massive decline in ridership that the MTA experienced during COVID-19. The resulting economic fallout from the depressed ridership necessitated billions of dollars in federal aid to keep the agency from going bankrupt.

At first, the agency released daily ridership numbers only via press releases or upon request. In response to requests from advocates, the MTA now has a website dedicated to its daily ridership numbers. A spreadsheet of the data since March 2020 is available, comparing daily ridership to pre-pandemic days in 2019. However, this is not currently on the state open data portal.

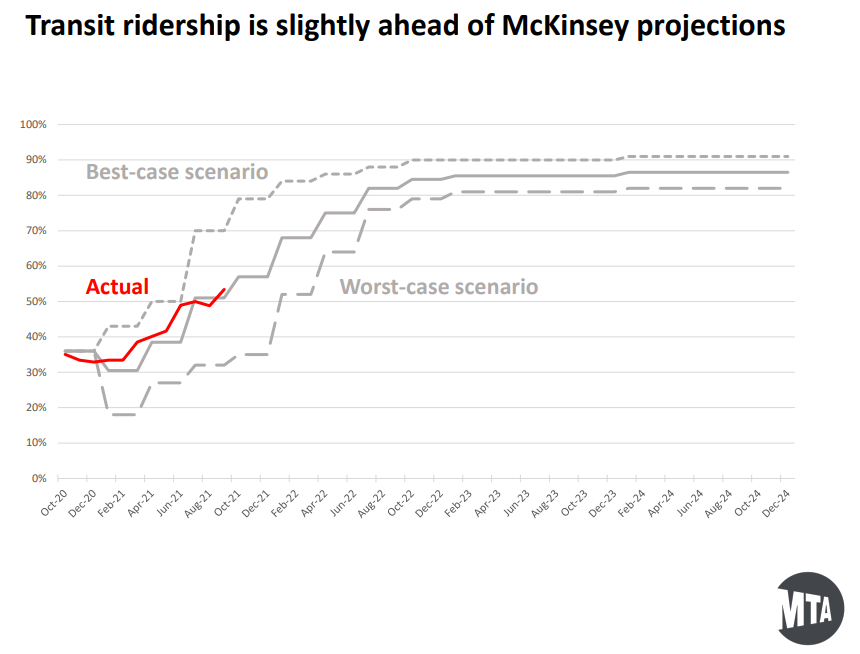

Additionally, the MTA in July 2020 began using McKinsey, a consulting firm, to project ridership numbers to help show the revenue impact of depressed ridership on the agency as it was seeking federal aid. The McKinsey ridership projections have also been used in developing the MTA’s financial plans. However, future ridership projections have not been released in open data, and have only been shared by the MTA in chart form. The chart below was published by the MTA in October 2021 as part of its board meeting presentation.

The MTA has said that it intends to hire a new consultant to produce updated ridership projections. As part of its contract, it should ensure that the raw data for the projections is released in an open data format. This way, policymakers, journalists, and advocates will have access to the data to compare ridership with the projections and better understand the MTA’s future.

2. Congestion Pricing Environmental Assessment

The MTA is in the process of conducting an environmental review of its congestion pricing program (called Central Business District or CBD Tolling by the MTA), which is currently slated to start in January 2023 after a two-year delay.

Congestion pricing has been strongly supported by transit and environmental advocates because it will raise $15 billion for the MTA’s 2020-2024 capital program and reduce traffic congestion. This is the single largest funding source for the latest capital program, and will fund critical improvements to MTA subways, buses, and commuter rails.

The MTA is expected to release its draft Environmental Assessment (EA), as required by the federal government, in May 2022 (see the program adoption timeline here). The EA will include a large amount of transportation modeling and analysis, with 14 different scenarios (“model runs”). These will show how different pricing structures, time of day pricing, and discounts and/or toll credits will affect traffic in the region and the effectiveness of the program – including how much money will be generated to fund the MTA capital program.

By law, the program must raise $1 billion annually to support $15 billion in capital bonds. A slide about the modeling and data that is expected to be generated is below, from a September 2021 staff presentation to the MTA Board.

The results of this type of data modeling are typically released as appendices of large PDFs that can be hundreds of pages (a traffic appendix for the now paused LaGuardia Airport Transit Access EIS numbered 353 pages for Part 1, and 300 pages for Part 2). The MTA can and should do better.

Open data on congestion pricing will help advocates help the MTA. If the MTA releases its traffic modeling data in an open data format, this lets the advocates and journalists have easy access to the information that will make the case for congestion pricing, and support the MTA’s efforts.

3. 20-Year Needs Assessment

Before the release of its draft five-year capital program, the MTA has released updates to its 20-year needs assessment, which provide the basis for determining the capital needs of the MTA based on regional population and ridership trends as well as the state of its existing infrastructure and assets.

Unfortunately, the MTA declined to publicly release a needs assessment before the adoption of its largest ever $55 billion 2020-2024 capital program, which is the only capital plan in the MTA’s history to not have an accompanying needs assessment released (only one other time, in 2000, was the needs assessment not released before capital plan adoption, but it was released soon after).

The MTA is now required by law to release its next 20-year needs assessment in 2023, which will be ahead of the adoption of its 2025-2029 capital plan. MTA staff recently presented plans for the assessment’s release. See the graph of some of the broad data on MTA assets that was included in this presentation.

Ahead of the September 2023 release, the MTA should ensure that all the data contained in the assessment is prepared in an open data format. This will help researchers and oversight entities better match the MTA’s assessment of its needs with its capital spending to ensure that the right investments are being made.

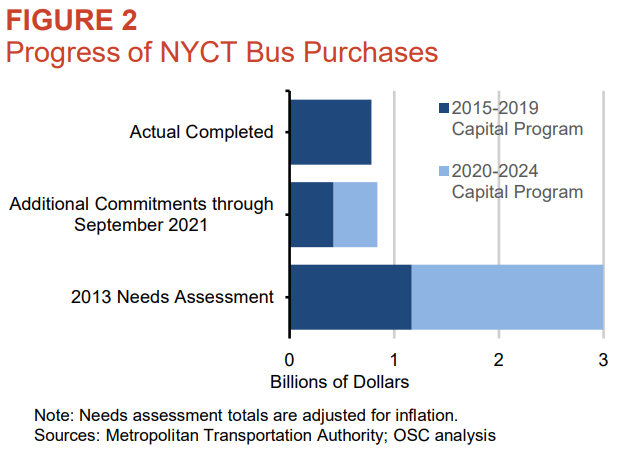

The State Comptroller in December 2021 conducted exactly this type of analysis, matching up the MTA’s capital spending on its 2015-2019 and 2020-2024 capital program with the 20-year needs assessment that was released in 2013, which included projected needs from 2015 to 2034.

See the chart of the comptroller's analysis of the progress made on bus purchases. The analysis shows that spending and commitments to date are below the actual need.

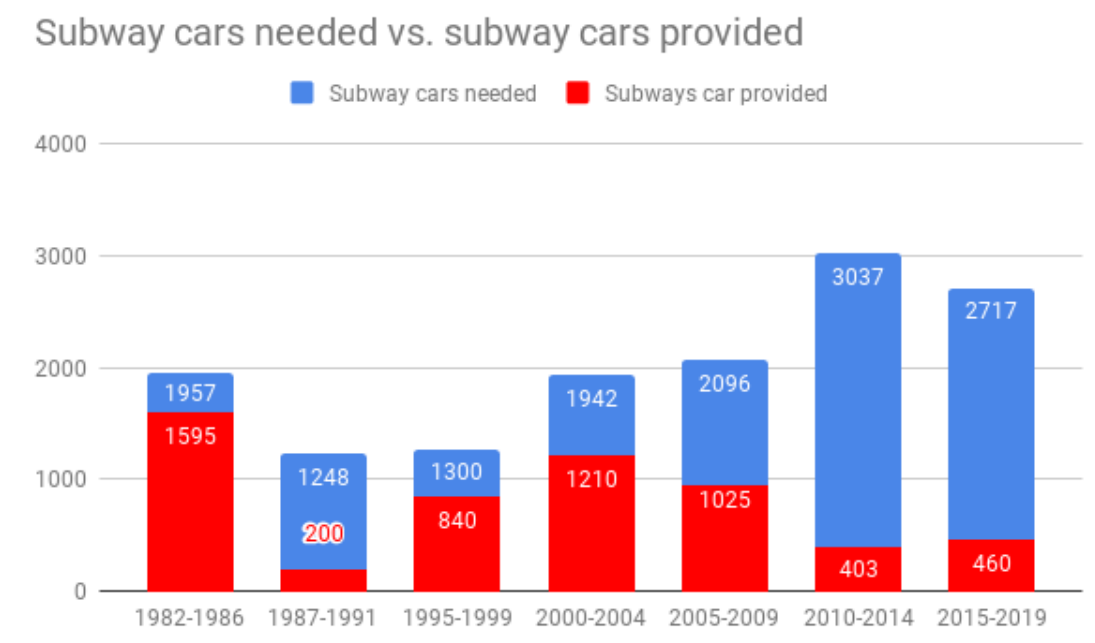

Reinvent Albany previously conducted an analysis of subway cars needed versus those purchased, building off of research by the Citizens Budget Commission. We found a similar lack of investment in subway cars compared to the stated needs, as seen in the accompanying chart.

Having the data to be able to match up the MTA’s needs with its spending is crucial for the accountability of billions in capital spending. Beyond the need for new buses and subway cars, there are large new needs related to resilience and climate change, as seen with the flooding in 2021 during Hurricane Ida and other storms. It is expected that the 2023 needs assessment will include a specific assessment related to resilience.

These three sets of data are just some of the information that the MTA should look to release as open data in the days and months to come. With an annual operating budget of $18.5 billion, the MTA generates a lot of public data that can and should be released to help shine a light on its operations.

***

Rachael Fauss is the Senior Research Analyst for Reinvent Albany, a government watchdog organization. On Twitter @RachaelFauss & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Rachael Fauss is Senior Policy Analyst at Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @RachaelFauss & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Thinking of Moving Out of New York City? Some Cautionary Words

Movie in the park (photo: @NYCParks)

First of all, full disclosure. My wife and I have owned a home near Woodstock, NY for years. My wife was brought up surrounded by nature in Pennsylvania and thrives on feeding birds and chipmunks, and I was born on 50th Street and 8th Avenue and am energized by street life, asphalt, and the A train. We live in the West Village, and have for many years, including through the pandemic.

As has been well-publicized, a slew of New Yorkers, no longer bound by having to go into the office full-time or at all, have been gravitating to living in the Hudson Valley, the Hamptons, the Berkshires, and elsewhere. While many are moving back, many others are surely still considering a move out of the five boroughs for greener pastures. But if you move from the city, here’s what you’re going to be missing. You’ve been warned.

1) You’ll Be Walking A Lot Less

Living in the city is to love to walk and wander through its streets, its neighborhoods, its history and character. On a walk in Chinatown, one sees plaques of where writers were born and where historical documents were signed, and ends up on Doyers or Pell Street for delicious dim sum. In the suburbs, you won’t be walking anymore -- and if you do, it has to be planned, a drive to a hike. The main reason you won’t is in most of these locales, there are no sidewalks or shoulders on the road. If you walk, you could die. And because you’ll be driving everywhere, you’re going to be gaining weight and feeling lifeless. New Yorkers (of the five boroughs) weigh eight pounds less than the average American because they often walk miles daily, without even thinking about it.

2) Say Goodbye to Bodegas

In virtually every neighborhood in the city, whether Windsor Park or the East Village, there’s a bodega or small deli, oftentimes several, that has all of the basics you need, from ice cream to toilet paper. There’ll be no more bodegas in the suburbs or country-side. Now you’ll be driving to a supermarket and wandering the giant aisles where bagels and lox are considered foreign foods.

3) Every Street in the City Carries Memories

The East Village is where you used to drink egg creams at Gem Spa, the Upper West Side is where you made stops at Zabar’s, and DUMBO is where you went for pizza at Grimaldi’s. Or whatever your versions of this as a city traveler. Each neighborhood has its own aura, feeling, and joie de vivre. But upstate, it doesn’t work that way. Kingston is a small city, with a street called Broadway, filled with gas stations and Chinese take-out joints. A nice place for a weekend getaway.

4) The Suburbs Sleep

New York City’s subway runs 24/7, many pharmacies are open all night, and you can get a sit-down dinner at midnight with ease. That won’t be happening in the Hamptons or Berkshires. Some Berkshire restaurants have their final call at 8 p.m., and some stay open later, until 9 p.m. At 10 p.m., most everything is closed.

5) Whom You’ll Be Meeting

In New York City, I have friends who were originally from Davenport, Iowa, Allentown, PA, Nigeria, Kenya, and Australia. Upstate and in the Hamptons, you’ll be meeting, almost exclusively, ex-New Yorkers. And most of them will simply tell you over and over again how overjoyed they are to have left a crowded, dirty city.

6) Nature Can Be Tough

While nature is not the prevailing value that New York City offers, there is plenty of it in the five boroughs and worth exploring if you haven’t. The coyotes who have roamed the West Side Highway, the owls in Central Park, and the falcon who nests off of Washington Square are all New Yorkers. But in the Hudson Valley, the 600-pound bears will eat your birdseed, turn over your garbage cans, and hide in the woods when you’re barbecuing then try to steal your steak and burgers. And did I mention the ticks that cause Lyme disease? They’re everywhere. You’ve been warned.

7) Watch Out for the Drivers

On local roads upstate, in the Hamptons and Berkshires, drivers speed. They know every twist and turn, and tend to drive 50+ on a 30-miles-per-hour road. Moreover, they often don’t make full stops at stop signs because they’re in a rush, likely for ice cream at Stewart’s because there are no bodegas in walking distance.

8) Hamlets are Hamlets

In the town of Woodstock, which has about 7,000 or so residents, many people know one another and travel in similar circles and track each other’s movements. They know the people who own the local health food store, where they spend their winter, and what their children are up to. Everyone knows each other’s business. In the city of New York, with 8.8 million people, only your close friends know about you, and the remainder of the city’s denizens pays no attention to you and let you live your life gossip-free.

9) Adjust Your Sensibility

In the city, if you’re looking for a cup of coffee and there are five or six people on line, you’re not going to wait. You’re going to walk 65 steps and find the next coffee spot. In the Hamptons, Berkshires, and Upstate, you’ll wait. If you walk 65 steps, you won’t find another cup, you’ll find a parking lot.

10) You’re Giving Up Proximity

Most things in New York revolve around proximity. You get to know your neighbors in your building, the bodega owner and workers, and others in your community. You can walk to do many things and you can get public transit to do everything else. Anything you could want to do, from a museum to a show to a baseball game to a hike to a continuing education class to shopping to you name it, is not far off. If you live in a house upstate as most people do, often in the woods, with no neighbors around, proximity won’t operate. You’re on your own but for a lengthy drive.

***

Gary Stern is a New Yorker.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

As New York’s Next Building Boom Approaches, It’s Time to Double Down on Construction Safety

Construction workers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

One look at the New York City skyline and you know that tens of thousands of workers have made their mark on this city. Ironworkers, carpenters, welders, plumbers, and electricians, among countless other tradespeople built New York – and they’ll also be the ones who ensure New York’s future is just as bright as its past.

Construction, however, is undoubtedly dangerous work, and without proper safeguards and legal protections, the work becomes that much more perilous. That’s why the unionized construction industry has dedicated itself to ensuring that safety is paramount at every New York construction site, and that the rigorous safety protocols required on union job sites become the expectation at non-union job sites as well.

A recent report by the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health (NYCOSH) is particularly alarming – it shows worker deaths in New York City and State leading the national average. This was the case even in 2020, when most construction activity was stalled as job sites were paused early in the pandemic. Construction workers made up 21% of the national average of all worksite deaths in 2020, while in New York State, 24% of worksite deaths involved a construction worker.

The numbers are particularly stark when you compare union and non-union worksites. In 2020, 79% of workers who died on private worksites were non-union, which is tragic, but unfortunately not surprising. Far too many non-unionized construction sites across New York flout safety protocols for the sake of profit, and these workers, many of whom are immigrants and people of color, fear retribution for speaking out about safety concerns – leaving dangerous and often deadly safety issues unaddressed. This is unacceptable. No worker, regardless of union affiliation, should needlessly lose their life and no family should have to grieve and suffer as a result.

So, what needs to be done to buck this alarming trend and ensure New York’s construction workforce can earn a good living and be safe on the job?

Let’s start with unionization. Joining a construction union is the number one way to protect oneself and one’s livelihood in this business. With mandatory training, robust and rigorous safety protocols, and a clear chain of command on jobsites, contractors have much less ability to set unrealistic and unmeetable demands that can and too often result in tragedy.

Increasing New York City Department of Building (DOB) inspections and ensuring adequate funding is a critical step, too. If all safety measures are being followed on a jobsite, workers, forepeople, and site owners have nothing to be concerned about. DOB is not out to harm the industry. These types of agencies keep us all safe, and those of us in labor support and appreciate their hard work and are committed to continuing to work with them to ensure essential safety protocols govern all construction sites.

By increasing New York State Department of Labor enforcement, we can further bolster worker protections and ensure worksites are safe. I am grateful Governor Hochul included an additional $12.4 million specifically for worker protections in her executive budget proposal. It’s a critical step forward that should be included in the adopted budget.

We must ensure that laws that deal with the worst-case scenarios, such as a worker fatality or serious injury, remain intact. This includes the Scaffold Safety Law, which requires that all safety measures are taken by the contractor and site owner and that functioning safety equipment is provided. This law is a critical protection for workers and keeps worksites and contractors accountable.

New York’s construction industry is an economic engine that powers New York, and it’ll also be the industry that leads the state’s and city’s economic revival, particularly with the significant investment generated by the federal infrastructure bill and Governor Hochul’s capital plan. As the construction industry continues to build back New York, it’s critical that there’s a renewed commitment to safety at all worksites. Laws designed to protect workers do not inhibit construction and investment – instead they’re the foundation that will enable us to make New York stronger and better than ever.

***

Gary LaBarbera is the President of both the New York State Building and Construction Trades Council and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York. On Twitter @NYCBldgTrades.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

This International Women’s Day, Let's Commit to Building a New York Economy That Works for Women

Ana Maria Archila, the author (photo: Claudio Papapietro)

It is said that International Women’s Day, which we celebrate today, March 8, started in 1857 when a group of women garment and textile workers marched in New York City for better wages and working conditions. Though this origin story is probably a myth — in fact, Women’s Day originated with a suffragist march through Manhattan six decades later — its popularity underscores that women’s liberation will only come when we achieve economic justice.

The pandemic made more visible the impossible challenge that women, and our families, face every day trying to balance the duties of care and work in an economy in which affordable childcare, housing, and healthcare are hard to find. At the same time, the pandemic exacerbated gender inequalities and laid bare a fundamental and often ignored truth; the success of our communities relies on the jobs done overwhelmingly by women, especially those of color.

For these women — providing childcare, health care, and keeping their families in their homes, working in restaurants, as street vendors and more — a return to a pre-pandemic “normal” is also untenable. We cannot simply go back to systems that didn’t work. New York must act with urgency and vision to deliver real economic gains for women, and, by extension, all communities.

Across the United States, nearly 2 million women left the workforce during the pandemic. Many have not returned. In New York, unemployment remains well above the national average. A recent report found that women with children in the New York metropolitan region were 70% more likely than men to be staying out of the workforce. According to the same study, women of color have been particularly hard hit, with higher unemployment rates than for white women.

These direct economic harms to women go hand in hand with more insidious forms of violence. In the pandemic’s early months, women were 20% more likely than men to experience hunger. At the same time, intimate partner violence has shot up. Ensuring women’s rights is not solely an economic matter, of course, but the interconnection of all these harms makes clear that economic progress is a crucial piece of the puzzle.

New York can take concrete steps towards addressing these issues, but we need leaders who will prioritize the dignity of women and rise to the occasion. Here’s some of what we can and should do this year:

First, we must pass universal childcare. A recent statewide study demonstrated that our childcare system is broken. Most parents either cannot afford to pay for childcare or live in a community without sufficient access to care services. Meanwhile, childcare providers — most of whom are women — are receiving inadequate wages and struggling to make ends meet. This system serves no one’s interest, least of all women. It is time for New York to step up and deliver a childcare system that works for all.

Second, we need to provide secure housing for all. This year, New York can take a critical step by passing “good cause” eviction legislation, which would stop landlords from evicting tenants who have been paying their rent and limit exorbitant rent increases. In the long term, we must work to transform quality housing into a right for all New York residents.

Third, we must raise workers’ wages and fund excluded workers. Tipped workers in the restaurant industry — a critical source of employment for women — are still not guaranteed the $15 an hour minimum wage. Governor Hochul has failed to lead on this issue. She must stand up for workers and ensure they receive a fair wage.

We should not stop with restaurant workers. We should also boost wages for home care workers — again, primarily women of color — and provide hazard pay to hospital workers.

Our state must also end the exclusion of workers from the state’s safety net by enacting “Excluded No More” legislation as part of the budget. This would replenish the historic, but depleted, Excluded Workers Fund with $3 billion and a permanent system for inclusion, to cover all workers who were left out from other pandemic relief while often doing essential work for our state.

Finally, we must also address gaping chasms in health coverage and care. This year’s budget must include “Coverage for All” legislation that would ensure that all low-income New Yorkers, regardless of immigration status, can access an Essential Plan. New York must also pass the New York Health Act to ensure truly universal access coverage and care.

As the mythical origins of International Women’s Day illustrate, the fight for women’s rights cannot be separated from the fight for economic gains like universal childcare, living wages, and dignified housing. But the mythical, and actual, origin of Women’s Day illustrates something else important too: it all started in New York. It’s time for New York to once again lead the fight for women’s liberation by electing leaders with the courage to fight for our economic rights. The state’s women know that we cannot return to the way things were before the pandemic. It’s time our leaders did too.

***

Ana Maria Archila is a Democratic candidate for Lieutenant Governor. She has been a leader in New York and nationally in the fight for immigrant rights, worker justice, LGBTQ rights, and women’s rights for two decades. On Twitter @AnaMariaforNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ensuring Transportation Equity in New York City

Council Member Brooks-Powers, the author (left), with MTA CEO Lieber (photo: William Alatriste/NYC Council)

For too long, New York City’s transportation conversations have focused largely on communities – both geographic and otherwise – that are best able to navigate our city’s streets, sidewalks, waterways, and subways. New York City is now at a pivotal moment where we are seeing historic funding from Washington, D.C. and the first female majority City Council. It is time to reshape the transportation and infrastructure conversation that for too long has left out the outer-boroughs and transportation desert communities.

Transportation equity is a major issue in our city that must be confronted, and I have begun working on it as the new chair of the City Council's Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. It requires addressing the needs of neighborhoods that have suffered from divestment, long commutes, often in two-fare zones, and a lack of transit access. It also calls for us to make our streets and public transportation ADA-accessible, ensure our children are safe traveling to and from school, promote the use of minority- and women-owned businesses (MWBEs) when we allocate our transportation dollars, and focus on improvement – not just enforcement – when we tackle dangerous driving.

Fundamentally, transportation equity can only be achieved by listening to the needs of all communities, and prioritizing people and places that need our efforts and resources most. To engage in thoughtful dialogue regarding transportation equity citywide, the Council’s Transportation and Infrastructure Committee is taking a comprehensive approach. We held our first oversight hearing on the topic this week, allowing transportation stakeholders to provide their insights. As, Chair, I have also embarked on a transportation and infrastructure listening tour of all 51 Council Districts. I want to talk not only to my Council colleagues and transportation advocates, but also to residents in different neighborhoods about how the City Council can help address their transportation needs.

Many of the challenges my district faces are experienced by neighborhoods across the city, and I’m excited to tackle these issues. It’s also important that we remember how these “citywide” issues disproportionately affect some New Yorkers, and question why that is and what we can do to change it.

One example of this is street safety. All New Yorkers suffer when our streets are unsafe, and no neighborhood is immune to the impacts of traffic deaths and injuries. Yet, a lack of focus and investment, historically from the city government, has left districts like mine – District 31 in Southeast Queens – to experience more traffic deaths than anywhere else in the city, based on data from last year. Much is the same in other districts like mine, from the Bronx to Staten Island. This means more of our friends and families are being hurt and killed on our streets. We need solutions that include addressing historic underinvestment that has left streets in some neighborhoods far less safe.

These disproportionate negative effects are also not limited to issues of street safety. As the data confirms, this also applies to traffic pollution, lack of accessible infrastructure, and other challenges.

As the Chair of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure in the New York City Council, I want to make sure that we address these important issues holistically, and our city agencies are responsive to the individual needs of communities. That means taking community input seriously and understanding that one solution may not work for every block in the city.

I am committed to making sure all of our communities’ voices are heard to achieve transportation equity across our city.

***

City Council Member Selvena Brooks-Powers is the Majority Whip of the City Council and represents the 31st Council District, which includes the neighborhoods of Arverne, Brookville, Edgemere, Laurelton, Springfield Gardens, Rosedale, and Far Rockaway. She is chair of the Council’s Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. On Twitter @CMBrooksPowers.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

I Had A No-Cost Childbirth, Other New York Moms Should Be Able To Do The Same

A new mom (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office)

When I had my first child, I couldn’t believe how expensive it was to give birth. Thankfully, I had no complications, but the bills related to my brief hospital stay added up and compounded the financial strain of caring for my new baby.

Eighteen years later, I was pregnant with my third child and worried that the costs would again be too high for me to afford. But this time, I was able to participate in the SEIU 32BJ Health Fund’s Maternity Care Program in partnership with Mt Sinai and my experience was a complete 180 from what had occurred nearly two decades earlier.

Every last dollar of my pre- and post-natal care was covered. I didn’t pay a single hospital bill out-of-pocket, which was an enormous relief, both emotionally and financially. My baby and I are happy and healthy, and I can now focus on saving for his future.

Unfortunately, not every New York mom is so lucky.

The Health Fund was spurred to create its Maternity Program in 2020 in response to the alarming statistics about the danger of giving birth in New York. Roughly 20 women die per 100,000 live births in our state every year, a higher rate than the rest of the county, which is already lagging far behind other developed nations in this important category. And it’s especially dangerous for women of color. Black women are more than twice as likely to experience life-threatening complications during or after childbirth and eight times as likely to die from pregnancy-related deaths.

Even when a pregnancy is routine and without complications, having a baby is still incredibly expensive – and the cost can vary widely depending on where you live, according to a New York State Health Foundation analysis. This is another reason why 32BJ’s no-copay Maternity Program is so important and beneficial to working moms.

It seems logical that a program with a proven track record and the potential to save lives should be expanded and replicated throughout the five boroughs so more mothers like me can benefit. But NewYork-Presbyterian (NYP), one of the city’s largest hospital systems, has threatened the program’s very existence. NYP wanted the Fund to either end the program to eliminate competition from other area facilities or allow NYP to offer it without guaranteeing to meet the high-quality standards that make the program so special.

A new piece of legislation introduced in Albany, the Hospital Equity & Affordability Law (HEAL), will help rein in out-of-control hospital prices and curb the anti-competitive contracting practices employed by hospital executives that block access to innovative care like the Maternity Program. When passed and signed into law, HEAL will enable the Health Fund to expand access to the program and establish a blueprint for other self-insured funds to follow at hospitals across the state.

At a time when new parents should be celebrating and bonding with their newborns, too many are instead worried about how to pay for their hospital bills. Giving birth and caring for an infant is stressful enough. More moms should be able to enjoy this life-changing experience like I did – without having to pay a single cent toward the highest-possible quality care.

It is far past time for the state to do everything possible to improve outcomes for moms and babies – especially moms of color, who face unnecessary and life-threatening challenges when giving birth in New York. Making HEAL a law would be a good first step. I hope state lawmakers and the governor act during this legislative session, so more mothers can get the kind of care they both need and deserve.

***

Shaunte Turner is a member of 32BJ SEIU and works in the cleaning division at Madison Square Garden.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Compounding Relationship Between Violence and Urban Inequality

Emergency (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office)

At the start of the 1960s, just over four out of every 100,000 Americans were murdered each year. The murder rate rose sharply during that decade, and then fluctuated between 8 and 10 murders per 100,000 for most of the 1980s and early 1990s, before it began to fall in the mid-1990s. By 2014, the murder rate had fallen to 4.4 murders for every 100,000 people, back to where it stood at the beginning of the 1960s.

That year, 2014, was one of the safest in our nation’s history. It is also the year when the trend shifted. In the years since 2014, the murder rate has risen by almost 50%, to 6.5 murders for every 100,000 people.

This is the latest headline that has been broadcast out to the nation. But the headline misses a fact about American violence that is crucial to understanding both its causes and its consequences.

In many cities with relatively high levels of violence, some communities are untouched by shootings and assaults, while others experience extreme incidents of violence on a regular basis. One of the most robust findings about violence is its concentration within a small number of street segments, intersections, city blocks and neighborhoods, characterized by racial and economic segregation.

The spatial distribution of violence is remarkably stable: In a study of violence in Chicago’s neighborhoods over 56 years, we found that the most violent Chicago neighborhoods in 1965 have continued to have the highest levels of violence in every period since, all the way through 2020.

Shifting our perspective from cities to neighborhoods changes the meaning of the latest national trends. From 1991 to 2014, when the murder rate fell by roughly half, the most disadvantaged neighborhoods, and the most disadvantaged segments of the population, benefited the most. Life expectancy rose most sharply for Black men, the racial achievement gap narrowed the most in states where violence fell the furthest, and economic mobility improved for young people who were raised in places where violence was steadily falling.

But as violence has risen over the last six years, the same communities have been hit hardest. When we analyzed data on fatal shootings from the 100 largest U.S. cities, we found that the recent rise of violence has been concentrated in areas characterized by poverty and racial segregation. Over this period, neighborhoods with lower poverty rates experienced a 59% increase in fatal shootings. High-poverty neighborhoods experienced an 89% increase. In neighborhoods composed of a majority of Black Americans, the rate of fatal shootings rose by 87%, while all other neighborhoods saw a 60% increase.

These trends are a continuation of a long-term pattern. When violence rose in the United States from the 1960s to the 1990s, it was felt most acutely in areas marked by concentrated poverty and racial segregation. When violence fell from the 1990s to the 2010s, it fell the most in these same communities. Violence continues to be concentrated in neighborhoods that experience multiple forms of disadvantage, from poverty to disease to segregation to joblessness. The question is why?

The answer takes us back to the middle of the 20th century, when a set of social and economic forces combined with federal, state, and local policy to create a crisis in American cities.

As jobs in the manufacturing sector began to disappear, middle-class families took advantage of subsidies to leave central cities, joblessness rose and poverty became more concentrated in central city neighborhoods left behind. As political power and government resources shifted to the suburbs, public housing complexes and schools deteriorated, sidewalks were not maintained, and public parks were left untended.

Instead of responding to this set of challenges with investments in central city communities, the federal government disengaged from urban issues and responded with punitive social policies that have exacerbated the problems faced by urban populations. The abandonment of central cities began under President Nixon, who argued that urban neighborhoods should be left on their own to deal with rising poverty and joblessness.

In the subsequent decades, federal investments in central cities have typically been implemented on a small scale and only for a limited timeframe. Never has there been a systematic effort to deal with the problem of urban poverty through sustained, large-scale investments in the people and the institutions of the nation’s city neighborhoods.

Punishment, on the other hand, has been the most consistent response to urban crime, violence, and poverty. Harsh state policies, such as eliminating parole and establishing mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses and violent crimes, combined with more aggressive policing and prosecution at the local level to push more Americans into the apparatus of the criminal legal system and to keep them enmeshed within this system for longer durations of time.

Our nation’s response to extreme urban inequality created the conditions for violence to rise. As political influence and public funding declines, core community institutions like schools, daycare centers, parks, playgrounds, libraries, and other features of the built environment are less likely to be supported and maintained. Flagging investment in local infrastructure leads to poorly lit spaces, abandoned lots, and empty buildings that are vulnerable to becoming areas of violence.

Robert Sampson’s research on collective efficacy demonstrates how the concentration of social and economic disadvantage can undermine social cohesion and trust among residents, making it less likely that they will take active steps to reinforce shared expectations for behavior, work together to solve problems, and achieve commonly shared goals for the community.

The relationship between disadvantage and violence is reciprocal. Inequality causes violence, but violence amplifies inequality. Violence disrupts learning, leads people to retreat from public spaces, leads businesses to close shop, and leads parents to seek a way out of the neighborhood. In the U.S. context, the prevalence of violence frequently leads to a shift in the central institutions and actors within a neighborhood. Representatives of the criminal legal system, including police officers, parole officers, school safety officers, and detectives become dominant figures in public spaces, and squad cars, sirens, and police tape become common features of the landscape. When we mapped data on shootings with data on police violence and incarceration, we found that the neighborhoods where violence is concentrated are the same neighborhoods that have experienced extreme levels of imprisonment and police shootings.

It is crucial to avoid the tendency to report these statistics on poverty, race, incarceration, and violence without an accompanying explanation of the link. In the United States, long-term disinvestment in central city neighborhoods has reinforced segregation by race, ethnicity, and income, weakening community institutions and undermining community residents’ capacity to work together to solve common challenges.

Our nation’s response to violence, and to the challenge of extreme urban inequality, has relied heavily on the institutions of punishment. This has compounded disadvantage. Communities with high levels of violence are also places where police violence is more common and where a large segment of the population is entangled within the expansive apparatus of the criminal legal system. It is a mistake to look at this and conclude simply that where there is violence, we should expect high levels of incarceration. The pattern of compounded disadvantage is a result of the unique American response to the challenges that emerged in central cities in the late 1960s; a response that featured the dual strategy of abandonment and punishment.

The fall of violence from the early 1990s to the mid-2010s makes clear that high levels of violence are not inevitable. One of us (Sharkey) has argued that violence fell because of a set of efforts to transform urban space, through both aggressive policing and intensive surveillance as well as through the mobilization of local community organizations who worked to reclaim public spaces and build stronger neighborhoods. But the fall of violence was precarious, because the dominant methods to respond to violence haven’t changed over time. The United States has not undertaken a large-scale, sustained agenda of investment to confront extreme urban inequality.

Our national approach has meant that when violence falls, the most disadvantaged communities will benefit the most, and when violence rises, it is these same neighborhoods that suffer the most severe consequences. And through the ebbs and flows, our reliance on police and prison means that a large segment of the population will experience the dislocation that comes with a period of imprisonment, and entire communities will continue to feel the resentment that comes from seeing their neighbors and family members mistreated by the police.

The trends that we have documented, and the spatial convergence of violence, segregation, poverty, institutional decline, and incarceration, lead us to the following conclusion: it may not be possible to address the challenge of American violence in a sustainable way without addressing the much larger challenge of extreme urban inequality.

***

Patrick Sharkey is a professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University and the founder of AmericanViolence.org. Alisabeth Marsteller is a pre-doctoral research associate at Princeton University. On Twitter @patrick_sharkey and @aamarsteller.

This column is part of a series published by Gotham Gazette and appearing in the inaugural issue of Vital City, a policy non-profit focused on developing practical and actionable solutions to public safety problems.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Gun Violence is The Crime Problem

Mayor Adams & President Biden discuss gun violence (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

In 2020, there were 375,800 fewer serious crimes in America compared to 2019, about a 5% decline. Amidst the overall decline, one specific type of crime ran counter to trend: murders, most of which are committed with guns, were up by 5,000, a rise of nearly 30%.

How should we think about these statistics? Should we be happy that serious crime is down or concerned about the increase in homicides? We argue this trend is actually bad news overall. As Berkeley criminologists Franklin Zimring and Gordon Hawkins have noted, crime is not the problem – gun violence is. This distinction has a number of implications for how we think about criminal justice.

Our logic might be easiest to see through analogy. The U.S. in 2020 also saw a decline in the total number of respiratory viral infections, driven by a massive reduction in the seasonal flu. But amidst this overall decline, there was an increase in one new, specific kind of respiratory virus: COVID-19. The result is that amidst a large decline in illness, the number of deaths from flu increased from the normal level (30,000-60,000) to over 600,000.

What’s immediately obvious from this analogy is that every virus is not the same. The public health consequences of the seasonal flu versus COVID-19 are vastly different. Because COVID-19 is so much deadlier than the seasonal flu, billions of people around the world fundamentally changed how they lived their lives. Online replaced in-person, with devastating effects on social life and the economy. A whole generation of schoolchildren were unable to make normal progress in their studies, or in learning how to get along with their peers. The elderly lost contact with their children and grandchildren.

A CDC-sponsored survey in the summer of 2020 found that 40% of American adults were struggling with their mental health during the pandemic. Among people ages 18-25 the figure was more like 70%; fully 1 in 4 young people said that they had considered suicide. Meanwhile, as a direct result of our behavioral responses to COVID-19, the global economy was devastated. In the U.S., the unemployment rate of 3.7% in 2019 surged to 8.9% in 2020.

As with COVID-19, so with crime. Property crime accounts for around 80% of all crime in America. For the victims of a pickpocket or a break-in, crime is a major irritant. For retailers, protecting and insuring against shoplifting and employee theft is a real cost of doing business. But property crimes are rarely life-changing events for the victims. And while the threat of property loss might lead us to take extra care to lock our cars, or install an alarm system, it doesn’t substantially impair the quality of our lives.

In contrast, the fear of gun violence substantially distorts the way that millions of people live their lives. There is increasing evidence that children who witness gun violence tend to underperform in school and have a variety of psychological problems that interfere with normal development. In response to gun violence, families that can afford to move often do. One estimate by economists Julie Berry Cullen and Steve Levitt suggests that, on average, a neighborhood murder has 70 times the effect of other crimes in persuading households to relocate.

A high-violence neighborhood suffers reduced property values and business investment. Employers and people of means seek more attractive places to locate. Reduced tax revenues make it harder for the surrounding city to address these challenges. It is easy to see the linkage here between endemic violence and poverty.

The Nobel-laureate economist Thomas Schelling came up with a way to measure the total social harms from different social problems – what people would be willing to pay to avoid or have less of them. A reduction in serious violence would have tangible effects on property values and the cost of the myriad activities to avoid and mitigate victimization, such as long commutes to the suburbs.

“Contingent valuation” studies, where a cross-section of the public is asked how much they would be willing to pay for reductions in different types of crimes, provide further evidence. One study of this sort by Mark Cohen of Vanderbilt and colleagues estimated the public’s willingness to pay for each prevented crime equaled: $5,098 for larceny, $21,666 per stolen car, $44,606 per burglary, $108,329 per aggravated assault, $356,849 per armed robbery, $369,593 per rape, and fully $15.04 million per murder.

Crime overall may have declined by about 5% in 2020, but the social harm from the rise in murders, most of which were committed with guns, more than offset the reduction of several hundred thousand fewer reported crimes total. The result is that, on net, the total costs or harms of crime in America (murders plus all other crimes) increased by $72 billion according to the willingness-to-pay framework.

If the problem of crime in America is indeed first and foremost a problem of gun violence, several important implications follow. The first is to ensure that law enforcement agencies prioritize violence prevention. “Public safety” begins with protection against fear, injury, and death.

Further, the victims of gun violence, most of whom are from low-income communities of color, need help of all kinds. They also need to believe that their cases are being taken seriously. Ensuring accountability for gun violence can improve public safety without exacerbating the problem of mass incarceration; murders account for only about one-tenth of one percent of all arrests. In a country where the share of unsolved murders increased from 1-in-20 in 1965 to 1-in-3 today (and is more like 1-in-2 in cities like Chicago), law enforcement in America for some reason made 1.5 million arrests for drug charges in 2019 – the vast majority of which, research suggests, have very little public safety value.

We must account for the consequences on crime, especially violent crime, when we are thinking about how much to invest in social policies. New York’s summer jobs program for teens is a case in point; knowing that this program not only provides valuable income and work experience to young people, but also reduces homicide, is surely relevant for decisions about how widely to scale those efforts. Another example is the effort to clean up vacant lots in Philadelphia, which might initially be thought of as a ‘nice to have’ in a city struggling with so many other big problems – until we see in the data that such beautification efforts reduce gun violence.

While some criminologists have disputed large estimates for the social costs of gun violence on political grounds, fearing that they may be used to justify policies they don’t like (such as imprisonment), the large burden gun violence imposes on society is equally an argument for more spending on social programs.

The direct victims of gun violence tend to come from a fairly narrow slice of society, but the threat of gun violence has far-reaching implications. It is serious violence that does the most damage to our quality of life. We recall the “crack” era a generation ago and shudder. As gunplay once again becomes common in formerly peaceful neighborhoods, peace of mind is among the victims.

***

Philip Cook is the ITT/Terry Sanford Professor of Public Policy Emeritus at Duke University. Jens Ludwig is the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago. Thanks to Elizabeth Rasich for valuable assistance.

This column is part of a series published by Gotham Gazette and appearing in the inaugural issue of Vital City, a policy non-profit focused on developing practical and actionable solutions to public safety problems.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.