NYCHA buildings in Harlem (photo: David Schalliol)

Mayor Bill de Blasio and his administration have turned heads with bold plans for lifting 800,000 families out of poverty, boosting school performance, and making the city more livable and equitable for all. His OneNYC plan aims to do nothing less than convert New York City into a progressive Sweden on the Hudson. The affordable housing component of the plan, the outline of which was first announced last year, alone promises to help finance construction of 80,000 units of below-market subsidized housing, extend subsidies for 120,000 existing units, and stimulate construction of 160,000 market-rate apartments, in part to relieve overall pressure on prices.

Mayor de Blasio's planned investments stand in clear contrast to the strategies available to leaders of many other U.S. cities, such as Baltimore and Detroit, where permanent economic decline has rendered city halls all but helpless. De Blasio's broad ambition is laudable. But the truth of the matter is that the figure that matters most for the mayor's legacy is 178,000: the number of apartments in the city's public housing portfolio. If Mayor de Blasio doesn't fix NYCHA first, every other initiative will be forgotten.

NYCHA - the New York City Housing Authority - is an irreplaceable asset — home to half a million or more poor New Yorkers, some in the workforce and some living on disability and old-age pensions or other public assistance. Apartments are comfortably sized. Most are in decent neighborhoods, and some in highly desirable ones, with access to transit, shopping, and other services. Rents, which are tabulated as a share of a tenant's income, average just $464 a month. Evictions are rare, and only for egregious violations of policy. During the past recession, when many working families at NYCHA lost their jobs, having a public housing apartment prevented homelessness. Most complexes also offer a range of on-site social programs.

But these apartments are suffering from chronic underfunding and deferred maintenance after a decade and a half of attacks by conservative lawmakers in Washington on funding for public housing. (Historically, approximately fifty percent of funds of maintenance and operation came from federal grants.) What had been America's best big-city housing authority, known for a solid level of service and balanced budgets, now shows signs of severe strain.

Elevators have not been replaced or repaired quickly; major capital projects (facades, bathrooms, pipes, and roofs) have been deferred. Many local maintenance positions on NYCHA grounds — the key to swift repairs — have gone unfilled. Thousands of remaining staff still make millions of repairs every year, but leaky walls, aging pipes, and unsound parapets often undo even the best efforts. Inflexible union rules, a legacy of more financially flush eras, further complicate maintenance goals. The mayor's decision to move more homeless families into NYCHA buildings is adding further stresses, as the rents these families can pay is even less likely to cover costs than that of the current mixture of tenants.

Allowing this disinvestment to continue will devastate families and communities across the city. And further decline in conditions would cancel out any benefits of the new housing the mayor has called for, not least because few NYCHA residents are financially stable enough to qualify for the new units or would be lucky enough to secure one, given that homes are distributed by lottery and demand far outpaces supply. Most important, replacement — should conditions slide far enough to require that — is all but inconceivable, with construction costs for 178,000 new apartments estimated at $66 billion.

[Inside a NYCHA building (David Schalliol)]

Mayor de Blasio ran on a strong platform of revitalizing NYCHA and there are some encouraging signs of progress. New subsidies have been earmarked for NYCHA by the State of New York for the first time in years. And an impressive $3 billion dollars has also been promised by the federal government, although not through usual housing funds but in the form of disaster relief to aid 33 NYCHA developments damaged by Sandy.

Locally, de Blasio's NYCHA Chair, Shola Olatoye, has decentralized maintenance operations, returning control to on-site managers. Renovation contracts have been streamlined and are moving forward. A quick decision was made to sell a half-share in certain privately built complexes that had been developed under HUD's project-based Section 8 program but that were never up to NYCHA standards for quality, and that are now too far-gone for NYCHA to repair on its own. An additional 16,093 deteriorated units are planned for partial sale.

Of equal importance, de Blasio has begun relieving NYCHA of many expenses, making it more like a typical city agency than a semiautonomous authority responsible for generating its own income. Under this initiative, the city has installed new security cameras, relieved NYCHA of annual payments for policing and PILOT (payments in lieu of taxes), subsidized NYCHA community programs, and will shortly assume responsibility for 1,000 NYCHA administrative and clerical staff. Chair Olatoye has also announced plans to raise fees for parking and improve rent collection, although these will likely face resistance from residents.

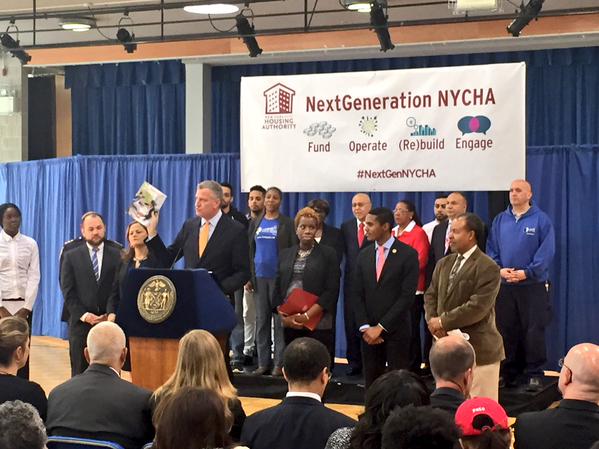

[Mayor de Blasio unveils his new NYCHA plan (photo: @CoreyinNYC)]

But Mayor de Blasio needs to do much more to keep the system from falling into complete disarray. Billions of additional dollars for capital improvements are needed (by one reckoning, $17 billion) to bring NYCHA complexes back to the high standards of earlier eras and ensure the health and safety of tenants. Yet unlike in those earlier eras when the city could count on Albany and Washington for aid, the only entity today with the liberal will to devote that kind of money to public housing is New York City itself.

The most promising solution is for city leaders to create a permanent, dedicated capital fund for rebuilding NYCHA with clear annual targets rather than dole out a limited amount each year as is done today, such as the $300 million recently allocated for roof repairs — an amount that is far less than required to undo the mold and leaks found in far too many buildings. To address the real scale of renovation needed, it may even be necessary to create a new city entity, outside NYCHA, with renovation of public housing as its sole purpose.

The proposal to lease or sell NYCHA parking lots, now back on the table with the administration's NextGeneration NYCHA plan, also merits wide support because it can yield additional millions, perhaps hundreds of millions, of dollars for these necessary repairs. Some residents will lose their parking spaces and views, but the potential benefits to NYCHA residents as a whole outweigh any losses to individuals. Shifting the 10,000 NYCHA staff who will remain on NYCHA's books to city payrolls will also be required because rents paid by tenants are simply too far out of line with the agency's high wages.

The New York City Housing Authority's vast system is the legacy of a great period of liberalism in the U.S. that started in the 1930s and has endured in New York, despite many challenges, while fading elsewhere. The best way for Mayor de Blasio to reinvigorate broad support — locally but also in Albany and Washington — for the kinds of liberal programs on his agenda is to prove that existing ones like public housing are flexible, solvent, and of the highest quality. The 178,000 families who call NYCHA apartments home will hardly benefit from universal prekindergarten and other generous new initiatives if their homes become unlivable. And if that happens, Mayor de Blasio won't be remembered for much else.

***

by Nicholas Dagen Bloom and Matthew Gordon Lasner

Nicholas Dagen Bloom is associate professor at New York Institute of Technology and Matthew Gordon Lasner is assistant professor at Hunter College. They are co-editors of the forthcoming book "Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies that Transformed a City."