Understanding the Labyrinth: New York's Ballot Access Laws

photo (cc) Taekwonweirdo

Just how hard is it to get on New York's ballot? Go here to Play Bump the Birds, Gotham Gazette's new ballot access game and find out. Are you smart enough to get on the ballot - and tough enough to stay there?

If you have attended a street fair, shopped at a green market or even walked along a city street, you have undoubtedly seen them smiling, holding clipboards, asking for a moment of your time to please sign their petition. All three citywide offices, including mayor, the five borough presidencies and all 51 City Council seats are officially up for grabs this year, and candidates have been busy collecting signatures for petitions needed to get on the ballot.

Only 10 months ago, New Yorkers expected a far more frenzied political landscape, since all the citywide officials, four of the borough presidents and 32 City Council members were about to be forced from their office by term limits. Then, in October, the City Council and the mayor decided to give themselves more time in office, extending the number of consecutive terms they could serve from two to three. Many candidates were waiting, hoping to run for the open seats of council members who would have been term limited, but now only eight council districts will see completely open races with the incumbent not running for re-election. Most incumbent council members will be running to represent their districts for one more term, as will all the borough presidents -- shrinking the pool of choices for voters. Although most of the current office holders face challengers, the incumbents will go into those contests with a clear advantage.

To learn about getting on the ballot read "Getting on the Ballot in Other Cities."

Another factor has historically narrowed the pool of competition even further: New York's cumbersome ballot requirements. New York is one of a handful of states that still requires all candidates -- incumbents and challengers -- to file petitions with voter signatures to secure a place on the ballot. Those petitions have to comply with a complicated list of requirements for the signatures to be considered valid.

This has turned the whole petition process into a political blood sport. Candidates with experienced election lawyers can bump many of their rivals off the ballot by challenging the validity of their opponents' petition signatures, disqualifying the signatures from the candidates' total signature count. These errors can include unclear handwriting, or the absence of a zip code or borough.

The lengthy and complicated rules have created a system that hinders healthy competition, according to candidates, voters, good government groups and even some election lawyers, who make their living by knowing these intricate ballot access laws. They use them to help candidates stay on the ballot and even kick off the competition.

A Guide to New York's Ballot Access Laws

New York's notoriously cumbersome election laws were created in the late 1800s to democratize the election process. Up until then, party leaders controlled which candidates were placed on the ballot. However, today's petitioning requirements ensure that only those candidates with huge campaign war chests or party backing have the wherewithal to get on the ballot -- and stay there.

Here's a nuts and bolts synopsis of New York's ballot access process from the New York City perspective:

In order to get on the New York City primary election ballot this year, candidates could begin collecting signatures for their designating petitions on June 9 -- 37 days before the last day to turn in designating petitions for the primary election

The law is very specific about how many signatures candidates must collect. They have to get 5 percent of the enrolled voters of the political party in the political unit covered by the office -- council district, borough or the entire city -- or the specific numbers enumerated in the state's Election Law, whichever is less. For a candidate for City Council, that number is 900 signatures, but as a cushion against petition challenges, the rule of thumb is to obtain at least three times the legal minimum.

The candidates also must figure out is who is eligible to sign the petitions and who can collect the signatures. While only registered voters who are members of the candidate's political party and reside in the district in question can sign the petition, any registered voter who is a member of the candidate's political party and lives in New York City can collect signatures. Voters are allowed to sign just one petition per office.

The candidate has approximately five weeks to collect all of the requisite signatures and file his or her designating petitions with the main city Board of Elections office between July 13 and 16, which complies with the state law requirement that designating petitions be filed between the tenth Monday and the ninth Thursday preceding the primary election.

That done, the challenge portion of the petitioning process begins. According to the board's rules, it conducts a prima facie "review [of] each cover sheet and petition to ensure compliance with the New York State Election Law." This marks the first round of challenges to the candidate's petition -- but definitely not the last. The law allows any voter registered who can vote for the candidate to file written objections with the Board of Elections challenging that candidate's designating petitions. Those challenges must be made within three days of the filing of the petitions.

Once challenges are filed, the board holds hearings to assess the validity of the challenges and issues a determination. In order to appeal the board's decision a person must commence an action in state Supreme Court, the lowest level court in New York's court system, "within 14 days after the last day to file a petition or within three business days after the board makes a determination regarding the invalidity of such petitions, whichever is later."

If the appeal involves a determination about whether a candidate's name will appear on the ballot or a voting machine, the Supreme Court, if possible, is supposed to issue a final order at least five weeks before the day of the election. Candidates can appeal such decisions.

A Ballot Access Case Study

The Feb. 24 nonpartisan special elections for City Council held earlier this year offer a classic example of how the state's ballot access laws can cause major headaches for voters and election officials. Running for the Staten Island seat vacated by now U.S. Rep. Michael McMahon, candidate John Tabacco was a target of aggressive challenges by the current council member, then opponent, Kenneth Mitchell.

Tabacco faced two separate challenges. Like all candidates running in nonpartisan elections, Tabacco had to select a symbol for his "party." He made the mistake of selecting a five-pointed star, the official ballot sign of the New York State Democratic Party, which contributed to his unstable ballot status.

The other challenge involved the board assessing the validity of his signatures. The board re-examined some of Tabacco's petition signatures and decided that many of the signatures he collected were invalid; therefore his total collection failed to meet the number needed to appear on the ballot. After much legal wrangling, the day before the election, the Appellate Division restored his name to the ballot.

In preparation for the election, the board had already sent the voting machines to the poll sites, without Tabacco's name listed. With the legal decision coming less than 24 hours before the polls were set to open, the board had to swiftly shift to conducting the election on paper.

These last minute changes can be costly to candidates and taxpayers alike. In Tabacco's case, he said the petition challenges claimed 75 percent of his time during the special election in February, leaving him little to no opportunity to fundraise and campaign. He eventually lost to Mitchell, coming in fourth.

Of the total $179,983 he spent on the campaign, Tabacco said, approximately 28 percent went for election lawyers, political consultants and campaign volunteers related to meeting the petition requirement and defending the signatures in the legal process. "It's a completely outrageous, disgusting process," Tabacco said

The lengthy back and forth that can sometimes happen with ballot disputes, does not just cost the candidates. In District 49, the expense of all the paper ballots with the last-minute changes was eventually passed on to taxpayers. After including the cost of transporting the unused machines to and from the poll sites, staff to coordinate the move, and the printing of paper ballots for all the voters, the Board of Elections spent $132,564 on this election. Over $50,000 of that went for paper ballots.

Insiders' Perspectives on Ballot Access

Another candidate who ran in a Feb. 24 special election, George Dixon, a long-time resident of East Elmhurst and a former member of Community Board 3, has a slightly different take than Tabacco about the petitioning process -- probably because he had an election lawyer and didn't spend as much time in court as Tabacco.

"The upside is that you get someone out there and recognized in the community. The downside is that there are various reasons why a signature may not be considered valid," he said, noting that signatures can be removed if a piece of required information is missing, like the date or the county of the voter. "When you challenge a community of signatures, you're not challenging the candidate, you're challenging the voter," Dixon said.

Jerry Goldfeder, an election lawyer at Stroock, Stroock and Lavan LLP who worked on Julissa Ferreras' campaign against Dixon and other candidates in the Queens special election, said that there are better systems than petitioning for getting a candidate on the ballot. "I've been a long-time advocate of abolishing the requirement that one needs petitions to get on the ballot," Goldfeder says. "There are other ways to show community support to become a candidate, such as the number of donations, or perhaps a filing fee."

Election lawyer Henry Berger, agreed. "The petitions' challenges in New York are one of the tactics used to discourage people from running for office," he said.

Some claim the city's nonpartisan special elections present even more burdensome signature requirements than regular elections because candidates have to rush to get the required number of signatures in a much shorter time period. If challenged, the time period to appeal and stay on the ballot is much shorter as well.

Reforming New York's Ballot Access Law

Proponents for changing the ballot access laws argue that, under the current system, candidates are required to collect too many signatures with too little time, a task that can be difficult if you do not have the support and resources of a political party behind you. They say that, in effect, these laws diminish voter choice by only leaving one or two names on a ballot and excluding community members who might be credible candidates, but are unable to raise the funds necessary to withstand aggressive ballot-bumping. Candidates whose signatures are challenged, have to spend time in hearings with the Board of Elections and in the courts, taking precious time away from increasing their name recognition and campaigning. Perhaps more importantly, it drains financial resources.

One recommendation for reforming the state's labyrinth ballot access laws calls for reducing the number of signature candidates needed to appear on the ballot. Good government advocates also argue that other broad changes to elections can create a more level playing field for new candidates. Proposals include nonpartisan elections, ranked voting, independent redistricting and public campaign financing. Getting the access laws changed, though, poses a real challenge. Whatever they may cost voters and the public, these laws also benefit incumbents who want to remain in office and stymie competitive elections. Given that, it's no wonder that these laws have not been reformed.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel and Andrea Senteno is the program associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Additional reporting for this article was provided by Alex Kane, an intern for Gotham Gazette.

Where Is New York's Lieutenant Governor?

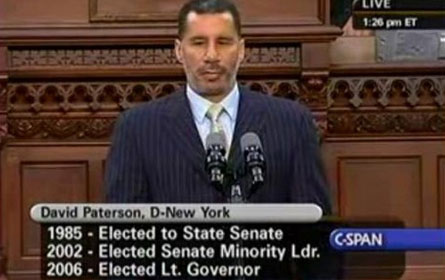

On March 17, 2008 when New Yorkers and the news media were focused on the resignation of Gov. Eliot Spitzer, few, and probably only hard-core political wonks, considered the effect Spitzer's resignation would have on the office of lieutenant governor since the then lieutenant governor, David Paterson, was about to become governor.

Now, over a year later, the lieutenant governor position remains vacant. Questions about the lieutenant governor's post have gained far more prominence given the very slim Democratic majority in the Senate. New York law allows the temporary president of the Senate, who is also the majority leader, to perform all of the duties of the lieutenant governor during the vacancy or inability, and Temporary President of the Senate and Majority Leader Malcolm Smith no doubt wishes that there were a Democratic lieutenant governor to give his Democratic caucus a much-needed tie-breaking vote. So does the temporary president of the senate get to vote twice if needed to break a tie vote? For obvious reasons Smith would love for the answer to that question to be a resounding YES.

The Conundrum of the Lieutenant Governor Vacancy

Unfortunately for Smith, however, while the New York State constitution empowers the lieutenant governor to act as the president of the Senate and also cast votes in that body, he will not be getting that extra Senate vote any time soon. That is because, the law does not specifically allow for the office to be permanently filled. Even worse, the law is about as confusing as can be with respect to how long the temporary president of the Senate fills this new dual role and how having two posts affects the temporary president's role as leader of the Senate chamber.

One would think that the current situation is only confusing because the situation is so unusual. Quite the contrary is the case, however, because lieutenant governor vacancies and their political consequence are old hat. At this point in the state's history, on nine separate occasions, a governor vacated that office and the lieutenant governor moved in to fill the vacancy.

This begs the question then: Why doesn't New York have a clearer and more concrete process for filling a vacancy in the office of lieutenant governor? Political realities of Albany politics aside, this convoluted process must be due at least in part to the state's complex and lengthy constitutional amendment process.

Passing a constitutional amendment in New York is a multi-step and multi-year process. In layman's terms, first the legislature has to introduce a bill proposing a constitutional amendment. Then that bill has to be reviewed by the state's attorney general to determine its effect on other sections of the constitution. After the attorney general approves the bill, then the Assembly and Senate have to pass the bill by majority vote before the end of the two-year legislative session. At the start of the new two-year legislative session after the succeeding general election, the bill passed during the previous session must age for three months before the legislature can vote on the constitutional amendment again. Assuming passage at this stage, the constitutional amendment must finally be approved by the voters.

In practice, this timeline means that even if legislators could decide on which process for filling the lieutenant governor vacancy they wanted to adopt for New York at this time, they would have to vote on the bill before the end of June 2010 and then again in 2010 or 2011 after the general election before putting it to the voters.

What Other States Do

If the Legislature takes the timing constraints seriously and gets down to the details, there are a few procedural options for how to fill this vacancy. According to a new report Filling Vacancies in the Office of Lieutenant Governor, published by Citizens Union, the nonprofit advocacy arm of Citizens Union Foundation, Gotham Gazette's publisher, 30 states specifically delineate a process for filling lieutenant governor vacancies.

Among those that have a process, the most common procedure - used by 14 states - is for the governor to appoint someone to the post who may or not be subject to some form of legislative confirmation. Ten of these 14 states, including California, Florida and Maryland, allow the governor to fill the appointment with a confirmation by a majority of both houses of the legislature. But some states like New Mexico, which amended its law in 2008, require that only the Senate confirm the governor's appointment.

Another seven states, such as Connecticut, Hawaii, Pennsylvania and South Carolina, either allow the temporary president of the Senate to automatically fill the vacancy, or make the temporary president serve in specifically limited capacities - like New York's process. At the other end of this spectrum, New York could adopt Alabama and New Jersey's practice of holding a special election to select the next lieutenant governor. The final option, which is used by two states - Rhode Island and Texas -- may be more in line with New York's tradition of appointing commissions or task forces to study issues. These states create a special senate committee that elects a replacement.

Currently pending in the New York's Legislature are at least six bills that adopt various forms of the processes for filling lieutenant governor vacancies used nationwide. The diversity of the proposals presents the Legislature with a variety of options, but in order to institute any change the governor and Legislature are going to have to act soon.

What Should New York Do and How to Get There

As any casual follower of Albany politics knows, change is slow, or at worst unlikely. So does that mean that New Yorkers are likely to be without full representation in the state capital in the form of a lieutenant governor? Unfortunately, the answer is yes. This is not only due to the potential for Albany inaction on this issue, but also because the timetable for passing a constitutional amendment means the legislature does not have enough time to act before New Yorkers elect a governor and lieutenant governor in 2010.

Even though it may be too late to change the current process for filling lieutenant governor vacancies before 2010, it does not mean the elected officials in Albany get a pass this time or that the fire is out and therefore Albany should do nothing. New Yorkers deserve full representation in Albany at all times, especially since the lieutenant governor is one of only four statewide elective offices, so elected officials have a responsibility to change the law to avoid this problem in the future - when, given New York's history, this ultimately will happen again.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Additional reporting for this article was provided by Jessica Lee, an intern for Citizens Union Foundation.

The Legislature Takes on Election Reform

The new Democratic hold on the State Legislature has made headlines for many things these past few months other than an increase in legislative activity or at least the appearance of one. Last year, good government advocates speculated that if Democrats won the State Senate and broke the decades long party split between the two houses, it would either be a new day in Albany or a test of the party's true commitment to reform.

While the Democrats have yet to receive a glowing review on the way they have handled some state matters, there is some indication that election reform is receiving increased attention. Even though the issue is widely seen as off radar during this economic crisis, there are currently over 50 bills in the Senate to amend election law. The Assembly has over 170 bills. A number of these measures -- some of them small -- could improve elections for New Yorkers.

Changes Big and Small

While it still seems unlikely that New York voters will be able to vote the weekend before an election, register and vote on the same day, or even sign up for an absentee ballot online anytime soon, some election legislation has jumpstarted the discussion. There are at least five different bills in the Senate and Assembly on early voting alone, and more on the implementation of Election Day registration, universal registration (where the government is responsible for keeping a list of eligible voters) and rules to amend the special election process.

Voting advocates have been pushing for changes like these for years. They argue that by making voting more convenient and by increasing opportunity and access to the polls, New York can increase its dismal voter participation record, which remains one of the lowest in the nation. Other states, such as Wisconsin and Minnesota who have programs like Election Day registration and early voting, are among those that boast some of the highest voter participation rates in the country. To remove some of the barriers to voting in New York's primary elections, a bill was introduced to shorten the lead time period for voters to change their party enrollment from the current requirement, which requires voters change party enrollment the previous year.

However, election reform is more than big changes, say voting advocates. It is also about the minor details that can make elections more transparent, accountable and secure. Recently, the Senate passed legislation that would count absentee ballots which were filled out in the correct poll site but at the wrong poll table. A long-held practice in many places, it is rooted in a court decision from 2005 (Panio v. Sunderland) that states being in the "right church, wrong pew" should not disqualify a citizen's ballot. The bill's sponsors also hope this measure would ensure that voters who receive an incorrect affidavit ballot, perhaps due to pollworker error, would still be able to cast a valid vote. It is now in the Assembly election law committee.

This proposed legislation seems to cover every aspect of elections. The bills target a wide range of problems, attempting to address long-standing issues with the state's administration of elections and even party politics.

One bill, for example, aims to require primaries for any special election to fill a vacancy in the State Legislature. Currently party leaders convene to select the official party backed candidate in a special election.

To address problems that have plagued poll site location, one bill would require all poll sites be handicap accessible according to the Americans with Disabilities Act. Another bill attempts to establish that no school serve as a polling place. In contrast, several voting advocates have argued that schools should be closed on Election Day so they can be used without compromising students' safety. And yes, there is legislation for that too.

Making Bills Law

Many have suggested that the good government platform -- including some election issues -- could make some real progress now that Democrats control both the Assembly and Senate. Other advocates, though, are quick to caution that the Democrats' true priorities will take shape as they settle into their fragile and newfound leadership role, and that pushing good government issues could still be an uphill battle.

Once bills pass through the appropriate committees in each house, they have to be voted on by the Assembly and Senate. It is widely speculated that the Assembly approved a number of reform bills in previous years knowing their passage in the State Senate would never come. With one-party control, both houses are likely to reevaluate their agendas, and issues that once sailed through the Assembly could encounter more opposition there. In addition, bills that pass the Election Committee in the Senate could meet a different fate on the Senate floor, especially since Democrats hold such a delicate majority.

A State Senate announcement this month that it would begin hearings across the state on election reform, though, gave advocates some cause for optimism. Sen. Joseph Addabbo, in the prepared statement, said, "We will address election issues with a deliberate approach, with hearings on voter registration, absentee ballots, election day and voting issues, Board of Elections oversight, new voting machines and other related matters."

Voting advocates hope these hearings will offer an opportunity to move the ball forward on many of the issues they have been pushing for. Aimee Allaud, elections specialist for the state League of Women Voters, said the hearings will "bring new opportunities for voters to speak to these issues which affect us every time we vote. New York needs to make additional progress in assisting all eligible voters to exercise the franchise."

Andrea Senteno is Program Associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.

Council Committee Frequency

| MEMBER: | STIPEND: | COMMITTEE: | NUMBER OF MEETINGS SINCE JAN. 06: |

| Eric N. Gioia | $10,000 | Investigations*** | 6 |

| Albert Vann | $4,000 | Community Development* | 7 |

| Inez E. Dickens | $10,000 | Standards and Ethics*** | 7 |

| Maria Baez | $10,000 | State and Federal Leg.*** | 16 |

| Alan J. Gerson | $10,000 | Lower Manhattan Redevelopment | 24 |

| Michael C. Nelson | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 29 |

| James Sanders, Jr.* | $10,000 | Veterans | 31 |

| Letitia James | $10,000 | Contracts | 32 |

| Domenic M. Recchia, Jr. | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 32 |

| Charles Barron | $10,000 | Higher Education | 32 |

| Kendall Stewart | $10,000 | Immigration | 32 |

| Sara M. Gonzalez | $10,000 | Juvenile Justice | 32 |

| Lewis A. Fidler | $10,000 | Youth Services | 34 |

| Darlene Mealy* | $10,000 | Women's Issues | 34 |

| Larry B. Seabrook | $10,000 | Civil Rights | 35 |

| David Yassky | $10,000 | Small Business | 35 |

| Simcha Felder* | $10,000 | Sanitation | 36 |

| Diana Reyna | $10,000 | Rules | 37 |

| Maria del Carmen Arroyo | $10,000 | Aging | 40 |

| G. Oliver Koppell | $10,000 | Mental Health | 41 |

| Gale A. Brewer | $10,000 | Technology in Govern. | 42 |

| Helen D. Foster | $10,000 | Parks and Recreation | 46 |

| Miguel Martinez* | $10,000 | Civil Service and Labor | 47 |

| Thomas White, Jr. | $10,000 | Economic Development | 47 |

| Michael C. Nelson | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 29 |

| Jimmy Vacca* | $10,000 | Fire and Criminal Justice | 49 |

| Joel Rivera | $10,000 | Health | 53 |

| Michael C. Nelson | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 29 |

| Bill de Blasio | $10,000 | General Welfare | 55 |

| James F. Gennaro | $10,000 | Environmental Protection | 55 |

| Helen Sears* | $10,000 | Government Operations | 57 |

| Robert Jackson | $10,000 | Education | 58 |

| Peter F. Vallone Jr. | $10,000 | Public Safety | 61 |

| Leroy G. Comrie Jr. | $10,000 | Consumer Affairs | 62 |

| Erik Martin Dilan | $10,000 | Housing and buildings | 71 |

| John C. Liu | $10,000 | Transportation | 82 |

| Melinda R. Katz | $18,000 | Land Use | 105 |

| David I. Weprin | $18,000 | Finance | 121 |

| * New Committee or New Chair *** Does not have a meeting quota. All other committees must meet every month, besides July and August. As of February, a committee would have been required to meet 31 times. |

|||

Special Elections: Better than the Alternative?

New York City recently held a special election to fill three vacant City Council seats in Queens and Staten Island. In the weeks leading up to the Feb. 24 voting, campaigns of the council hopefuls went into hyper-drive, filing petitions, raising money and knocking on doors. Now another campaign is underway -- this time for a special election on April 21 to fill the post of Bronx borough president, left vacant by incumbent Adolfo CarriĂłn's move to Washington to work in the Obama administration.

Special elections demonstrate some of the tough challenges of running a campaign in New York City, with a shortened time frame amplifying the pressure to win. Despite that, they are generally seen as a fairer way to fill vacancies than appointments -- which have come under attack following controversy surrounding the filling of U.S. Senate seats in New York and Illinois -- and can promote much needed, yet often lacking healthy competition.

How Special Elections Work

The City Council seats contested last month became open when their occupants - Joseph Addabbo, Hiram Monserrate and Michael McMahon - won election to other offices in November 2008.

In New York City, special elections to fill vacant City Council seats are nonpartisan, as opposed to special elections for State Senate or Assembly where party committees select the party candidate behind closed doors. (For more on this, see Citizens Union Foundation's report Circumventing Democracy.) This means that in municipal special elections, there are no official Democratic, Republican or Working Families Party candidates. Candidates must create their own party names and symbols to be put on the ballot next to their name.

Nonpartisan special elections provide the opportunity for greater competition, supporters of the system say. In the recent special election, six candidates were on the ballot in Staten Island's 49th District race, and in the two Queens races in District 21 and 39, there were four candidates on the ballot in each.

Once candidates submit their petitions, they confront ballot-bumping a favorite political sport in New York City where candidates scour arcane rules and regulations to try to push rivals out of the election. In a special election, the extra tight schedule means ballot challenges and appeals can easily consume entire campaigns. This was the case in District 49, where candidate John Tabacco fluctuated between being on and off the ballot several times, and was only finally reinstated on the day before the election. As a result, voters in Staten Island's 49th Council District had to vote on paper ballots. Tabacco lost.

The victors in the three contests will serve until Dec. 31, 2009 and will have to run again this fall if they want to secure their seat beyond that. Those who lost their races in February already may be gearing up to run in September's primary election. Often candidates who win special elections go on to victory during the regular election season -- particularly in the case of the partisan State Senate and State Assembly special elections -- but not always. Anthony Como won the 2008 special election in District 30 in Queens to replace City Councilmember Dennis Gallagher but went on to lose his seat during the 2008 general election, when state law required him to run again.

Replacements by Appointment

In contrast to holding a special election, state law provides for vacancies to be filled by appointment. According to New York's Consolidated Public Officers Law, Sec. 42, 4-a, the governor has the authority to make a temporary appointment to fill the vacancy, depending on when the vacancy occurs. For other positions, including state attorney general and state comptroller, the state legislature chooses who will fill the remainder of the term. In 2006, following the resignation of State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, then Gov. Eliot Spitzer and the legislature clashed over who should be appointed. The state legislature ultimately filled the position with an assemblymember, Thomas DiNapoli, rather than one of the governor's preferred candidates.

While special elections at the state and local level have been criticized for low voter turnout, New Yorkers recently saw some of the pitfalls of filling a seat by appointment when Gov. David Paterson had to appoint someone to Hillary Clinton's Senate seat after she became secretary of state. Following much speculation about whether he would name Caroline Kennedy, Paterson ultimately selected then U.S. Rep. Kirsten Gillibrand. The whole process was assailed in the press, prompting calls that the state holds special election to fill any future vacant U.S. Senate seats. There is some precedent for this as states including Oregon, Texas and Vermont, among others, select U.S. Senate replacements through special elections.

The Next Special Election

On March 2, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced the special election to fill CarriĂłn's seat will take place on April 21. This election has already been the subject of much press. State Assemblymember Ruben Diaz Jr. has already declared his intention to run and newspapers report that City Councilmembers Maria del Carmen Arroyo and Larry Seabrook also are exploring a run. This election - similar to the Feb. 24 City Council special elections -also will be nonpartisan, although, as with other city races, parties will be able to make endorsements. The Bronx Democrats have already endorsed Diaz.

While nonpartisan elections are one way of trying to increase the number of candidates that run in elections, other reforms that many good government groups have suggested include improved ballot access laws, campaign finance laws, strengthening voting rights and other election reform as ways to continue this trend of increased competition. As New Yorkers look to their next nonpartisan special election, it would be wise to consider what it takes to run a six-week campaign, and for those who can vote -- in this case, residents of the Bronx -- to go to the polls. It's one way to continue the process toward fair and competitive elections.

Andrea Senteno is program associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.

Rural Legislator, City Issue: How Upstaters Decide

Gotham Gazette image by Ya-Hsuan Huang

This year, New York City residents will see legislators from all over the state vote on issues that directly affect their lives. From the transit bailout to school control, rent regulation and perhaps even term limits, the city will watch legislators from rural areas, small towns and suburbs decide its fate. This drama plays out every year, but last year the defeat of congestion pricing and enforcement cameras for bus rapid transit left some New Yorkers wondering how legislators from outside New York City make their decisions when they vote on issues that only affect New York City.

What informs the thought process of upstate legislators when they vote on issues that seemingly relate only to the five boroughs? Which downstate legislators do they talk to for insight? And how much impact do upstate legislators truly have over New York City issues?

Many factors affect the way legislators vote. Who legislators know -- and who their friends and foes are -- influence which bills they back, which ones they oppose and where they will come down on issues that might not have much to do with their districts. If a powerful legislator, such as a committee chair takes a stand on a bill, legislators tend to fall in line so that they will have support on their bills in the future. Certainly belief and ideology, as well as campaign contributions, play a role as well.

A review of some recent debates and votes offers an indication of the complicated calculations that influence voting in the capital.

A Chairman's Prerogative

In the battle for enforcement cameras for bus rapid transit, one member of the Assembly from upstate New York was able to influence the outcome to his liking single-handedly. Some observers say arbitrarily.

Last year, Assemblymember Jonathan Bing of Manhattan introduced a bill that would have allowed the installation of traffic enforcement cameras on buses. These cameras would have photographed vehicles illegally using the rapid transit bus lanes and enable the city to issue tickets. The goal was to increase the speed and efficiency of the notoriously slow New York City bus system. Environmentalists and transportation advocates supported the bill. They expected that the measure, which was pending before the Assembly transportation committee, would easily get to the Assembly floor.

It didn't.

Committee Chairman David Gantt of Rochester, who has long opposed traffic enforcement cameras because of privacy concerns, held an impromptu committee meeting. Six members who had co-sponsored the bill then vote to "hold" the proposal, meaning it would not come to a vote during the legislative session.

According to witnesses and reporting by Streetsblog, the vote, instead of taking place during a regular committee meeting, was held in a hastily called meeting in the Assembly parlor. A number of members missed it, so were counted as voting yes -- in favor of the hold -- since under Assembly rules at the time an absence was treated as a yes vote. A number of legislators from New York City and even some of the measure's cosponsors were recorded as voting to hold the bill.

Gantt dismissed any outrage among the bill's supporters about the way the vote was handled. "They will have to answer that," he said and added "I get more press in New York City then in my own district cause of this stuff."

The number of cosponsors voting to table their own bill struck the New York Times as odd, so the paper ran a piece discussing it. The story quoted Bing saying, "This is such a specific New York City issue, it's one of the many things where you wonder why the State Legislature has any role at all."

Insiders say that Gantt used his influence to trade favors with legislators on the committee so that some of those who initially supported the bill voted with him to table it.

Why did Gantt act to kill the camera measure? He said he wanted to protect the public.

"The problem with bus cameras is, say you pull into a bus lane to drop your kid off to see the game at Madison Square Garden and get a ticket," said Gantt. "I'm worried about the public. It's the same as congestion pricing. I'm not against that, but we shouldn't do anything drastic in a hurry."

Gantt noted that his problem with bus lane enforcement cameras is similar to his problem with cameras used to photograph vehicles running red lights. "Say you let a friend borrow your car, and they get a ticket," he said. "It costs a ton of money to fight that ticket down there." Further, Gantt said, enforcement cameras do not help public safety but are simply "gimmicks" to increase revenue. "New York City is facing a budget gap and so is everywhere else, but you should make real cuts, not use gimmicks," he said.

Supporters of the measure clearly disagree. They believe creating rapid transit bus lanes would allow buses to move through traffic at a decent speed and help alleviate New York's severe congestion problem. They wonder if Gantt truly understood the impact bus rapid transit would have had on the city.

Critics also point to Gantt's sponsorship of a bill last year that would have allowed red light enforcement cameras to be installed at intersections in counties outside New York City. They have charged that the bill would have benefited CMA consulting services of Albany, which distributes monitoring technology. A former counsel to Gantt, Robert Scott Gaddy has a sizable contract to lobby on behalf of CMA Consulting. A Gantt staffer said at the time that Gantt never supported traffic enforcement cameras and only introduced the bill "to control the legislation -- to do what he wants with it."

The Geographic Schism

Observers tend to think the defeat of the bus lane cameras sprung more from one man's -- Gantt's -- strident opposition than from any gap between the city and upstate.

Assemblymember James Brennan of Brooklyn, who chairs the Cities Committee, does not see Gantt's concern about the enforcement cameras as an upstate vs. downstate issue. "It is an issue that affects Buffalo, Syracuse and places all over the state," Brennan said. "It is not just a New York City issue."

Neysa Pranger of the Regional Plan Association agreed. "Generally, legislators defer to those whose districts are affected by the legislation. It is unfortunate how it (bus rapid transit camera legislation) played out, but I think it had more to do with how he (Gantt) felt about the issue than regionalism," she said.

Bing said that he never had a conversation at the time with Gantt about why Gantt opposed the camera legislation. "I reached out to the chairman and said we would like to work with him to make amendments to the bill based on any concerns he had, just as we did with the New York Civil Liberties Union and the transportation unions, but not once did I hear why he was opposed to it," Bing recalled.

Gantt said he communicates with downstate representatives and said he talks largely with those who he thinks "want the best for the state as a whole." Those representatives include Richard Gottfried from Manhattan and Michael Gianaris from Queens.

Deferring to the City

Last year, supporters of a congestion pricing plan that would have charged commuters $8 to enter parts of Manhattan were shocked when Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver announced that the plan did not have "anywhere near a majority in the Democratic conference and will not be on the floor of the Assembly."

The proposal, pushed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, had support from the City Council, environmental groups and labor groups —as well as upstate Republican senators who Bloomberg had supported. It faced stiff opposition from legislators from Brooklyn, Queens and New York's suburbs, who said the plan was elitist and would hurt their constituents.

When the plan failed, supporters blamed outspoken legislators from outside the city, notably Richard Brodsky of Westchester. Critics slammed Brodsky, saying that he opposition stemmed not from concern for his constituents but his relationship with the parking industry. Streetsblog reported that in 2007 Brodsky had received more campaign donations from the parking industry than any other legislator, some $16,700 over a three-year period.

Whatever the reasons for Brodsky's opposition to congestion pricing, though, his suburban constituents would have been affected by congestion pricing more than, say, the constituents of David Gantt from Rochester. Further Brodsky was joined by many legislators from Brooklyn and Queens, who also stood against charging their constituents to drive in Manhattan.

According to Brennan, upstate legislators deferred to legislators from New York City and its suburbs on congestion pricing, and opposition certainly was not limited to one member or to one area.

"No offense to my upstate colleagues, but I think for the most part they didn't express their opinions on congestion pricing. It very much came down to concerns of people who were directly affected," Brennan said. "There is no basis for them to even think it was defeated by upstate members."

Personal Politics

In general, Bing said, members tend to yield to the wishes of legislators whose district would be most affected by a given proposal. "On most issues there is deference to a local legislator," he said. "That happened for congestion pricing. Upstate members deferred to downstate, and the reverse is true. …We tend to defer to the members whose districts are affected."

On upstate matters, Bing said, he relies on legislators including Crystal Peoples of Buffalo and Darrel Aubertine of Cape Vincent. "I would talk to Aubertine about guns and farms and I would tell him about downstate housing," said Bing.

Assemblymember Jack McEneny of Albany, said that the debate over congestion pricing in the Assembly was long and hard. He described the process: "We had this caucus to try to get on the same page, and it is very time consuming. But while we debated, Shelly wouldn't say where he stood. It was debated. Problems came up, like where the money goes, if it is going to transportation, the privacy issue and the specter of people dumping cars in neighborhoods. We would say, 'Shelly, where do you stand?' He would say, 'I don't want to tell you.'"

Finally, McEneny said, when it became clear there was not enough support to bring the bill to the floor members again pressed Silver on where he stood. According to McEneny, Silver responded, "'I'm from the Lower East Side. I'm for it for my constituents but I will go with the will of the conference."

McEneny insists that Silver ensures that his majority discusses issues at great length before moving on them. "Someone says we need an East Side subway stop? I say, why? They explain it," said McEneny. "We challenge one another. We spend tedious amounts of time in caucus and everyone gets to talk."

What would have informed McEneny's vote on congestion pricing had it come to a vote? "'All politics is local,' -- Tip O'Neill," said McEneny. "All politics is personal -- Jack McEneny," he continued. "I read the sponsorship more than I read the bills. I know by the name on the bill if it is someone who knows their stuff or if it is someone who is doing a favor for a friend."

McEneny said that while tensions between upstate and downstate existed in the past, he thinks upstate representatives have reconciled their issues with New York City. "After 9/11 people saw the list of names and realized that New York is the nursery for young professionals," said McEneny. "It is New York's economic engine. They said, 'That's our cash cow.' And we want our children to go there to learn and then come back home."

The Mayor's Role

The personal politics in Albany has posed challenges for Mayor Bloomberg, who has earned the enmity of many legislators for his attitude and for some of his political moves. It is said that a number of upstate legislators find Bloomberg arrogant, heavy handed and elitist.

Transportation advocates say antipathy for the mayor could have helped kill congestion pricing "Everyone hates the mayor, right?" asked Kate Slevin of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign. "You go to Albany with a plan with the mayor's name on it and it is very difficult. Go back with a plan with Richard Ravitch's name on it, and it is a different story. People don't like the mayor and the way he does business."

Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Campaign, a transit advocacy group, said there traditionally has been tension between the legislature and the mayor of New York. "The Tom and Jerry relationship between the state legislature and the mayor dates back centuries. There has always been this tension. One level of government always has it in for another level," Russianoff said.

That relationship between the mayor and the legislature will certainly influence upcoming action on school control, term limits, rent regulation and aid for the transit system.

The fact that the term limits issue has arisen in the capital at all could be viewed as a commentary on the mayor's popularity, along with legislators' reluctance to see out of work City Council members seeking their jobs. Assemblymember Hakeem Jeffries of Brooklyn has proposed a bill that frames the extension of term limits in the city -- and the mayor's push for a third term -- as a statewide issue. His bill would require any extension of term limits be put up to a public vote. To the surprise of observers the legislation has made it out of Assembly, and a similar bill has support in the Senate.

The fate of another issue dear to Bloomberg's heart -- mayoral control of schools -- could also hinge to some extent on distaste for, if not Bloomberg himself, his appointee: School Chancellor Joel Klein. During a series of recent hearings about mayoral control, legislators expressed their frustration about working Klein and his staff. While many of those irked at the chancellor represent New York City districts, Gotham Schools' Elizabeth Green has written, "I haven't found any lawmakers who don't complain about Klein."

The situation has led to speculation that a deal might be made to allow Bloomberg to keep some control of city schools -- if he gets rid of Klein. In the meantime, Klein reportedly has stepped up efforts to communicate with lawmakers in hopes that his effort will yield a better outcome for his boss.

The Power of the Purse

Bloomberg's campaign donations, largely to Senate Republicans, won him support on key issues, such as congestion pricing. It could also work against him. Sen. Suzi Oppenheimer of Westchester, chair of the Senate education committee, will likely have some say in the fate of mayoral control of schools. Perhaps unfortunately for the mayor, he gave money to Oppenheimer's opponent last year and, by some accounts, she does not seem ready to forgive him.

While money always figures in politics, it can be a particularly powerful influence when the issue at hand does not affect a legislator's constituents. The State Senate's stand on rent control provides an example.

Traditionally, the Democratic controlled Assembly would pass rent reform legislation only to see it languish in the Senate, which was controlled by upstate Republicans who greatly benefited from donations from the real estate industry. Many of those senators had no rent control -- and not many apartments--in their districts. To cement the upstate support, real estate interests ran advertisements in upstate districts telling viewers to call their legislatures to "oppose New York City rent regulation."

Now with the Senate having, as Bing put it, a new "urban Democratic majority," one would expect that to change. In general, with both houses controlled by Democrats -- and the three most powerful leaders in Albany all from New York City -- one would expect this to be a good time for issue dear to the Democratic city.

Things, though, might not be that simple. Faced with a thin majority and a few outspoken renegade Democrats, Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith is tiptoeing around sensitive issues. On rent control, for example, Smith said in a recent interview, that the rent regulation proposals passed by the Assembly still "need debate" in the Senate -- and will likely not be taken up until after the state's dire budget situation has been addressed. Insiders say that Smith is concerned that Republicans might be able to win back seats upstate if the Democratic majority is seen as focusing too much on downstate issues.

On top of all of this there is the simple fact that New York City legislators don't always agree. Disagreement between representatives of the five boroughs helped ensure congestion pricing did not come to a vote. It is almost certain that New York legislators will not come down united on school control.

In general, Smith minimized the idea of downstate vs. upstate concern. He believes the basic interests of his urban district in Queens are the same as those of communities in upstate New York, Smith said. Calling the divide a "psychological myth" created by Republicans," he said, "We have seen results of that in the form of a $15 billion deficit. Its not really upstate downstate -- it is people's interests vs. special interests."

Sen. Neil Breslin of Albany frames the same idea differently. "I think of it a lot like a baseball team," he said. "We might be from different places, but we are all playing for the same team to better New York."

A Call for Tighter Ethics Laws

Spend time in New York's Capital Region and you will be hard pressed to go very far without seeing former Republican Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno's name -- and not because of his recent eight-count indictment on federal corruption charges.

If you arrive in the region by air, one of your first few steps may lead you past a bust of Bruno at the Albany International Airport. If you catch a minor-league baseball game, you will probably visit the Joseph L. Bruno Stadium. During a walk through Saratoga Spa State Park you will likely encounter the Joseph L. Bruno Pavilion. The list of buildings that bear the former senator's name goes on and on, from a lobby in a local YMCA to a biotechnology research center and a town park.

Local leaders, Democrat and Republican alike, bowed to Bruno whenever they could to secure funding for their own pet projects or to get legislative favors. Bruno famously responded to questions about whether it was fair that upstate New York benefited so greatly from his power, "It's been our turn these last dozen years."

Bruno had a leadership position and as one of the three men in the room wielded large amounts of power. But the types of questions that now face Bruno have confronted many New York's politicians. Most have not been indicted, but concern about their behavior and their use -- or abuse -- of their offices has arisen nevertheless.

A number of activists in New York say this atmosphere of impropriety -- and constant suspicion of impropriety -- must end. With that in mind they have proposed a package of measures designed to change the way business is conducted in the state capital.

A Call for Changes

For his part, Bruno faces a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison and up to a $250,000 fine on charges that he traded his influence in the state legislature for financial gain. Among other accusations, the indictment alleges that Bruno's financial disclosures made from 1993 to 2005 did not include all required information and had misleading and false information. Those filings are required under the state's Ethics in Government Law. As Senate majority leader, Bruno had the power during most of those years to control the ethics committee that would have policed the transgressions Bruno is alleged to have committed.

At least some of the changes offered by good government groups would address that. The organizations want to set new guidelines that they think would reduce the chances that politicians will use their positions to enrich themselves financially and also would give constituents a clearer look into how influence is traded in Albany. They want to establish a new ethics commission that will oversee both the legislative and the executive branches. And they want more transparency and stricter guidelines on the use of campaign contributions.

Last week, members of New York Public Interest Research Group, Common Cause New York, the League of Women Voters of New York State and Citizens Union (whose sister organization is Gotham Gazette's publisher) gathered in Albany to ask for these changes and to challenge the new Democratic leadership in Albany to keep its promises to enact reform.

Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group said that politicians should be falling over themselves to do away with the perception that hangs over the capitol -- the perception that just about everyone in politics is a corruption scandal waiting to happen.

That does not seem to have occurred. Instead, the reaction was not overwhelming, according to Common Cause's Susan Lerner. DeNora Getachew of the Citizens Union said that she felt "this was just the beginning of a conversation."

Richard Azzopardi, a spokesperson for Sen. Craig Johnson, who chairs the committee on Investigations and Government Operations, said the proposals are "very thoughtful."

The Cloud of Suspicion

During interviews following his indictment, Bruno portrayed himself as an honest man who "needed to make a living." But take the time to stand in the shadow of the baseball stadium locals affectionately call "the Joe" and ask residents of Bruno's former district if they were surprised at Bruno's indictment. They will look at you like you've just asked them if they are surprised that leaves fall during autumn. They might say something such as, "He is a New York politician, right?"

Horner said an oversight body to police ethics for both the executive and legislative branches could give New Yorkers more confidence in their representatives' integrity. Currently, each branch has its own separate ethics watchdog. The Legislative Ethics Commission is made up of legislators from both houses. On the executive side, the Commission on Public Integrity has seven members -- all appointed by the governor.

In other words, officials basically police themselves. Horner, for one, thinks that presents a problem.

"Self regulation doesn't work," he said. "The system we have in New York for regulation is unusual in the entire country." Only four other states have similar oversight boards, 29 other states have one independent board that oversees the legislature and executive branches.

The Commission on Governmental Ethics, as proposed by the groups, would oversee both the executive and legislative branches of state government. It would have nine individuals. The governor would name three, and the comptroller, the attorney general, the speaker and minority leader of the Assembly, and the temporary president and minority leader of the Senate would appoint one member each. The executive director would be appointed by the chair and vice chair of the commission, who would be of different parties. Members of the commission would not be allowed to hold political office or be employed by lobbyists.

Horner isn't optimistic that the governor and legislature will approve this suggestion. "Politicians are nervous about the unintended consequences," he said. "They are loath to create an independent watchdog group. There is not enough public pressure for them to make the change. And the governor doesn't talk about it, so we will see."

In 2008, Paterson introduced a campaign finance reform bill, but critics say he has not pursued reform as tenaciously as his predecessor, Eliot Spitzer. "We want to not dictate campaign finance reform. We want to really persuade legislators that it is really the root of the dysfunction we have in Albany," Paterson has been quoted as saying. "We'd like to come to consensus with the two legislative bodies about curtailing it."

Paterson also has not adhered to the $10,000 ceiling on individual contributions that Spitzer imposed on himself. The governor said he would operate under the existing law that sets the limit for contributions at $55,900.

Increasing Transparency

The Ethics Reform Act of 2009 would require politicians to publicly disclose the names of all people they do business with and the amount of money they make from those business dealings. Currently, New York State law requires that public officials disclose the names of the businesses that employ them, but they do not have to report the amount of money they make or the names of their clients. Horner said that this lack of information can make it hard for constituents to know who is influencing who and can also create an appearance of impropriety where none should exist.

John Pikus, the special agent in charge of the Albany division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who oversaw the Bruno investigation, told the press that one reason the Bruno investigation took three years is because of the nature of the legislative process in Albany.

"The ability to understand the legislative process is difficult at best," Pikus said. "There are factors involved in which bills are passed, member items are approved, which never see the light of day. ... And that, really, from our standpoint, from the FBI's standpoint, was the problem. We can subpoena. We can provide opportunities for individuals to come in and talk to us, but the legislative process was almost Byzantine."

Preventing Abuses

The Ethics Reform Act of 2009 also would restrict the amount lobbyists and firms that receive state contracts could contribute to politicians and political committees. Lobbyists and those receiving government contracts also would be barred from serving on boards and commissions that make decisions on audits or the awarding of contracts. A database of lobbyists and contractors would be created to make it easier for the public to see who is peddling influence. And finally, laws on the personal use of campaign funds would be strengthened so that campaign money could not go to pay legal defense bills, tuition, mortgage, rent or utility bills, or dues and fees to country clubs -- as has been the case in the past.

Horner said he hasn't heard much support for these ethics reform changes this year, "The winners of the game rarely want to change the rules," he said.

He, however, does expect a renewed debate on better oversight, increased transparency and more limits on the influence of lobbyists and contractors. "If they address all three things," said Horner, "it will be a very good session.

Making Voting Easier

Image (c) ShooterD

With change in the air as Americans watched the inauguration of a new president and the start of a new year, New York's leaders are setting their agendas for 2009. This month Gov. David Paterson delivered his first State of the State address, focusing on the economy and the challenges facing New York. Mayor Michael Bloomberg's State of the City also emphasized an economic recovery plan. Both executives spoke about education and infrastructure issues, as well as the tough choices government will have to make this year. What was clear in both of their addresses -- mostly from what Paterson and Bloomberg did not say -- is that during these difficult financial times reform will be left on the sidelines, particularly election changes that would make casting ballots easier and more secure for New Yorkers.

In November, Paterson asked New York Secretary of State Loraine Cortes-Vazquez to issue a report analyzing the 2008 election and highlight potential reforms that could increase voter participation. Cortes-Velazquez's report is set to be released in February. Despite the impending report and pleas from advocates, however, many wonder how much of a priority election reform will be for this administration. With a new year ahead, voting advocates and many voters have their own ideas about changes big and small that would make the election process more accountable, more secure and more accessible.

Early Voting

The excitement surrounding the 2008 elections caused record voter turnout nationwide. Voters headed to the polls early in states that allow people to cast ballots before Election Day. The rules for early voting vary from state to state and can range from allowing residents to cast absentee ballots without citing a reason to establishing early voting centers with voting machines.

In New York, state law allows absentee voting only by residents who are absent from the county or too ill to vote in person on Election Day. Despite that, New Yorkers, apparently unaware that early voting is not permitted here, headed to their borough election offices days before the Nov. 4 election to cast their ballots. The New York Times reported that between 50,000 and 60,000 absentee ballots had been received by Oct. 28, and some voters waited up to two hours at their borough office to obtain and cast an absentee ballot. Their votes were included with those cast in person on Election Day. In a press conference, Marcus Cederqvist, executive director of the city Board of Elections, speculated that stories from other states might have led New Yorkers to believe early voting was available here.

Voter advocates have begun pushing for a change in the New York State constitution and state law that would allow voters to cast ballots before Election Day using an absentee ballot without requiring the voter to provide an excuse. No-excuse absentee voting would increase the number of people who would vote in advance of the election and ultimately boost turnout.

Register, Then Vote

Another election change aimed at making voting easier and more accessible to voters is Election Day registration, also know as same-day registration, which is currently allowed in nine states. Election Day registration lets voters both register and vote on the day of the election. In some states, voters are required to fill out an affidavit ballot, and after their eligibility has been verified, the vote is counted. In other states, voters register at a central location and then, on the same day, vote at their local polling place. Still others allow same-day voting if the voter casts a ballot before Election Day.

New York State offers none of these options. Instead people must register to vote at least 25 days prior to the election.

In 2004, New York ranked 46th in voter turnout across the country, and in the last five presidential elections (not including 2008), New York State voter turnout failed to exceed 51 percent of the voting age population. In contrast, in three of the states with Election Day registration -- Maine, Minnesota and Wisconsin -- voter turnout in the 2004 presidential election exceeded 70 percent.

In New York, Assemblymember Michael Gianaris sponsored bill A. 4488 during the 2007-2008 legislative session, which would have amended state election law to implement Election Day registration. This bill has not been reintroduced yet for this session.

Those lobbying for the change cite New York's abysmal voter turnout rates as a key reason for implementing same-day registration. Opponents, on the other hand, argue that the process would be too costly, would create more work for election officials and, if improperly implemented, make elections more vulnerable to voter fraud. None of the nine states with Election Day registration, however, reports increased voting fraud.

Universal Registration

Another election reform that has been receiving attention is universal registration. Under this practice, the government would compile a list of all citizens eligible to vote and use it as the official roster of voters. Anyone on the list would automatically be registered and would only have to show up on Election Day and vote. Lists would be compiled either from census records or by adding names from different municipal or state lists, like social service recipients or people registered with the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Proponents argue that universal registration would eliminate the problems voters encounter with not being on the rolls on Election Day and increase voter participation. A recent report from the Brennan Center for Justice entitled "Universal Voter Registration" examines the link between registration barriers and voter participation. At a recent City Council hearing, state Board of Elections commissioner Douglas Kellner said, "The concept is quite simple: Every citizen over 18 year of age, who is not incarcerated for a felony conviction and who has not been declared judicially incompetent should be entitled to vote. Period."

Other Reforms

Even without bold changes such as these, voting advocates argue that steps can be taken to improve the election process in New York. Modernizing election agency Websites, improving hotline capacity, better training for poll workers and increased access to the polls for disabled voters are among the many changes advocated by organizations like the Brennan Center, Citizens Union, Common Cause/NY, New York Public Interest and Research Group, the League of Women Voters of New York, the Women's City Club of New York and Center for Independence of the Disabled.

For some though, these small-scale reforms -- and the slow or nonexistent progress of the state's election agencies and city and state elected officials to implement them -- signal a need for greater changes to the structure of New York's election administration. Citizens Union (whose sister organization, Citizens Union Foundation, publishes Gotham Gazette) plans to issue a report in the coming weeks that discusses the importance of reforming how elections are run and a departure from what it characterizes as the old way of voting.

While reforming elections in New York state may not top anyone's agenda, at least publicly, for 2009, voters and advocates will no doubt continue to tell their legislators "out with the old, in with the new" when it comes to voting procedures in the state.

Andrea Senteno is program associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.

Will the State Senate Save Rent Control?

Photo (cc) bmercer

Michael McKee, the treasurer of the Tenants Political Action Committee, worked hard to secure a Democratic majority in the State Senate. Besides making substantial donations to the campaigns of Democratic Senate hopefuls last year, McKee said, more than 50 people from Tenants PAC worked to elect Joe Addabbo in his bid to unseat Sen. Serphin Maltese.

Why?

"We knew that as long as the Republicans were in charge we couldn't get the simplest, Mickey Mouse bill out of the Senate," McKee said. According to McKee, Senate Republicans received a steady flow of cash flow from the real estate industry that "kept them in power"and so had no interest in passing legislation that would be favorable to tenants.

Addabbo's campaign was successful, and the Democrats seemed set to become the Senate Majority. McKee expected the Senate would then easily pass housing legislation the Democratic-controlled Assembly had moved on year after year. Now, though, dissension within Democratic ranks has cast doubts over whether 2009 will be the banner year for tenants McKee and other advocates had hoped.

What Tenants Want

In general, housing advocates want to strengthen rent control and reverse many of the measures to weaken it that were enacted by the New York City Council and the Republican-controlled state government over the last two decades. The expected legislation includes A02005, which would would undo the law that allowed landlords to remove rent regulation on vacant apartments on which the rent had reached $2,000 a month rent. Advocates say the passage of A02005 would be a triumph for tenants since it would also restore to rent regulation some apartments that had been decontrolled.

Proponents of the bill in the Assembly say that rent decontrol encourages landlords to harass and mistreat tenants in rent controlled apartments to drive them out and then rent the apartments at market rates. Rising rents also make it difficult for tenants with regulated apartments to even consider moving. Meanwhile landlords have an incentive to lie about the pricetag of renovations on vacant apartments to artificially raise the value of the unit.

Maggie Russell-Ciadri, executive director of Tenants and Neighbors, said that ending decontrol is the single most important issue for tenant advocates. Experts say more than 50,000 rent-regulated apartments were lost between 2005 and 2008 because of decontrol.

Returning rent regulation to the city by repealing the Urstadt law has been a priority for many tenants' advocates for years. The Urstadt law, enacted in 1971 by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, took rent regulation out of the hands of New York City and gave it to the state. Therefore legislators from districts without much rental housing can influence the price of apartments in New York City. This year, though, advocates are less focused on repealing the Urstadt laws than they were in previous years and have made abolishing decontrol their focus.

Other bills before before the Assembly would address other tenant concerns. One, A1928, would make rent increases for major capital projects a temporary surcharge so that tenants could pay off the costs of improvements rather than having permanent increases in rent. Bill A2002 would increase penalties for landlords who harass their tenants.

Bill A168 would limit a landlord's ability to claim apartments for the use of their family. Now landlords are able to push tenants out of their apartments and some have been able to empty entire buildings to create luxury mansions. The bill would limit recovery for family use to one apartment. Other bills in the Assembly package are designed to close loopholes to keep landlords from drastically raising the rates of their rent controlled apartments.

Democratic Dissidents

Progress on these issues now seems unlikely to proceed as smoothly as tenants groups had hoped. Thanks to hard bargaining by three renegade Democrats who threatened to bolt the party -- the so-called gang of three -- the landscape in the Senate has changed from what many anticipated on Election Day. Sen. Liz Krueger of Manhattan, a passionate supporter of tenants' issues and the ranking Democratic member of the Housing Committee, was assumed to be in line for chair. She was bumped in favor of gang of three member Pedro Espada of the Bronx.

Housing advocates have voiced their displeasure at Espada's nomination, with some calling the gang of three "the Manchurian Democrats."

McKee said that Espada is simply the wrong person to chair the Housing Committee. According to McKee, when Espada served in 1993 as the ranking Democrat on the committee, he was "not only unresponsive" but also "destructive."

However, McKee said, "it's unclear how Espada will perform as chair" and how much it will matter. McKee said that he is sure the Democratic Senate, especially Majority Leader Malcolm Smith, realizes tenants' issues are "life and death" to them. In light of that, McKee expects the Democratic leadership will make sure the Senate does away with rent decontrol regardless of Espada.

Responding to complaints from tenant advocates, Espada said, "Maybe they don't know me." He added that the Section 8 subsidized housing program and tenant-protection issues are "very close to me."

Espada said he grew up on public assistance, has experience being homeless and worked as a tenant organizer. All this, he said, makes him sympathetic to the plight of the working family. "I'd like to meet an advocate who has experience that I don't have," said Espada. "I would ask for their patience and cooperation."

Espada seemed ready to take on broader issues as well. "It's a really exciting time in America," he said, explaining that he expected a "new urban reality," thanks to the Obama administration. "It's time to think beyond brick and mortar housing. We should be thinking out of the box. We should revisit the complete policy of how we assist cities."

One way to expand the supply of housing, he said, would involve making it possible for people to live upstate and quickly and affordably commute downstate. "We need to talk about how we get workers in Manhattan to Sullivan and Ulster counties to live there. There are ghost towns there now. "

As for his loyalty to the agenda of the majority leader and the Democratic majority, Espada said, "As a whole there is a clear synergy, but the idea that we should all be on automatic pilot is ridiculous. We are going to have to take each issue as it comes--not just draw up battle lines, but look at the merits of each issue."

Meanwhile in the Assembly

As housing advocates wonder exactly what they can expect from the Senate, their old allies in the Assembly appear more than ready to push ahead as they have in the past.

Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver released a statement earlier this month pledging his support to "protect working families who are struggling with the cost of housing." Assembly Housing Committee chair Vito Lopez has already held hearings on rent regulation.

It is expected that next week the Assembly will move to pass the package of pro-tenant legislation

McKee has grown accustomed to seeing the Assembly take action on tenants issues while knowing the legislation will die because of inaction by the Senate. This year he has considerably more hope, but there is still a great deal of uncertainty.

The Senate Looks at How It Operates

With their majority finally solidified, the State Senate Democrats last week passed rules changes, which they say, are designed to create more legislative transparency and to balance the power rift between the majority and the minority. Even though the Democrats had moved on reform issues after years of pleading for the same courtesy from the Republican leadership, their actions were greeted with derision by some and a tempered optimism by others.

The changes reverse rules instituted by the Republicans in 2001. Good government groups like the Brennan Center for Justice hope that such amendments will lead to more transparency in the Senate, give the public more input into the legislative process and allow members of both the majority and minority to freely propose and debate legislation.

What the Rules Do

One of the new changes will allow any senator to co-sponsor a bill without permission from the author. Previously, majority senators could prohibit members of the minority from being co-sponsors of their legislation.

Another change will allow senators to file "motions of discharge" to force bills out of committee after 20 days. Previously senators would have to wait 60 days. The longer waiting period allowed the majority to easily block a bill sponsored by the minority by keeping it in committee. The minority could ask for a floor vote, but votes against allowing the legislation to move forward were not a matter of public record.

The rules changes also promote the use of technologies such as the Internet to give the public greater access to the legislative process.

These changes will all expire at the end of the year and will likely be replaced by changes recommend by the newly established Senate bipartisan temporary Committee on Rules and Administration Reform. The committee will have 90 days to hold hearings and make recommendations on rules changes.

Good government groups have said that, while they would have liked more aggressive action, they are happy that reforms were made and are optimistically awaiting the recommendations of the temporary Committee on Rules and Administration Reform.

Sen. Daniel Squadron, who campaigned on reform issues, said, "I am pleased we have made real changes. It might not be everything but it is a real start."

Republicans called the Democrats' proposals weak and demanded more drastic changes to balance power. "This proposal does not go far enough. Right off we're starting on the wrong foot." Sen. George H. Winner Jr. told the New York Times

Some Democrats could not help but giggle. One Democratic senator described the Republican's change of heart as "a convenient conversion," and the "height of political theater and cynicism." "At least we have put the ball on the field," the senator said. Republicans had moved on rules changes in the past. An amendment in 2005 left Democrats displeased.