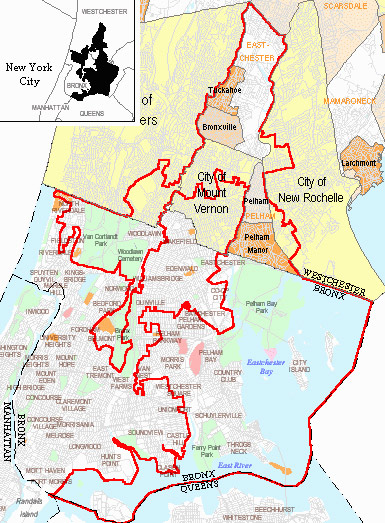

Bronx Senate District 34: Klein Goes for Three

Jeffrey Klein is finishing his second term representing this district that includes part of the Bronx and Westchester. Klein, who was then a member of the State Assembly, won the office in a hotly contested race in 2004 after the longtime incumbent, Guy Velella pled guilty to taking bribes.

In Klein's bid for a third term, he faces Daniel Fasolino, a retired police officer who has also been a real estate broker and homebuilder. In an interview with the Journal News, Klein said his key priorities included property tax relief and cutting spending to reflect the state's straitened economic circumstances. Fasolino cited his key concern as "the tax situation."

According to his 32-Day Pre General filing, Klein raised more than $48,000 in the reporting period and had almost $756,000 on hand. Figures for Fasolino were not available.

Tracking Building Inspectors

photo adapted from p0ps Harlow

The inspectors are now under inspection. As of Oct. 1, the New York City Buildings Department began tracking its inspectors with Global Positioning System technology via their cell phones. Supervisors can see where the inspectors are at any given time, pull up archives of where they were the day before and even watch their minute-by-minute movement -- all they need is Internet access and a password.

The department's move faces opposition from the Allied Building Inspectors Union. The friction stems mostly from what the union claims is a lack of information about how the system will work and how the department will ensure that the technology does not follow inspectors during their time off.

The Department's Many Woes

The program comes amid building department efforts to cope with a year of controversy that, among other reforms, resulted in the resignation of former Commissioner Patricia Lancaster last year. The latest scandal came last week when six inspectors were arrested for bribery, and prosecutors accused the Luchese crime family of infiltrating the department.

Over the past five years, the Buildings Department has seen at least one bribery incident every year. Often inspectors themselves reported the bribe attempt to the Department of Investigations, which then worked with buildings to arrest the briber.

Tracking will certainly not solve all the department's problems. Knowing the location of an inspector does not immediately reveal wrongdoing in cases like bribery, said buildings department's spokesperson Tony Sclafani.

"This is one step to ensure integrity, but it's obviously -- it's not going to be the catch-all," said Sclafani.

Tracking Offenses

The Department of Investigation has worked closely with the Buildings Department on a number of cases in which GPS tracking would have indicated inspectors were not where they were supposed to be.

Following the crane collapse in March 2008 that killed seven people, the city arrested building inspector Edward Marquette. Marquette had allegedly falsified his inspection of the site 11 days earlier. Another inspection was conducted the day before the accident.

A press release on the investigative report published this past March states that the investigators "found that the DOB crane inspection and permitting protocols would not have identified the rigging errors that caused the collapse."

GPS would have sent warning signals about an elevator inspector who was on the payroll of the Buildings Department as an inspector and of the Metropolitan Transit Authority as an elevator maintenance supervisor. On his timesheets, he claimed to have worked for both departments simultaneously.

In a statement on the arrest, then Commissioner-designate Robert LiMandri promised to begin using GPS technology to ensure inspectors arrived at their sites. Even without GPS, though, the department's Office of Internal Audits and Discipline picked up on the discrepancies, which resulted in an investigation and the inspector's arrest.

Of the GPS program, the investigation department emailed this statement on Sept. 25: "DOI is supportive of any measure that improves supervision and strengthens integrity, accountability and safety for city inspectors." Neither of the departments addressed specific inquiries about whether the Department of Investigation will have access to the GPS software or records in the event of an investigation.

A Trend to Track

The department's revamping efforts have resulted in a dozen new laws, more money for oversight programs and reorganization of leadership. So why make the extra effort to monitor inspectors even more closely? Sclafani said the three main goals were "integrity, efficiency and safety."

President of Local 211 of The Allied Building Inspectors Union, Joseph Corso, disagreed. "Public perception. Sounds good," said Corso. "That's what they're doing. They're placating the public."

Other city governments that have instituted similar programs also have faced resistance. In Massachusetts in 2006, the public safety commissioner suspended 20 inspectors who refused to accept phones that had the GPS capability needed for tracking. Here in New York, the GPS technology can be activated on existing phones,

Inspectors in Bridgeport, Conn., were fired after the fire department secretly placed GPS tracking devices in their government vehicles and found inspectors using the cars for personal use. The inspectors went to court to argue that the devices were illegal according to state law. A judge rejected their argument.

New York City has its own experience tracking government employees. The Fire Department has Automatic Vehicle Locators in all of the city's fire trucks and ambulances. Fire department spokesman Steve Ritea said that the system allows the dispatchers to send the closest vehicle to the scene of a fire or other emergency.

The Buildings Department, though, will track people, not vehicles. It has signed up to use Telenav Track, a product of Telenav designed to follow the movement of employees who work outside the office. The product's website advertises that employers "get more from your mobile workers" with minute-to-minute tracking to "keep your finger on the pulse" and alerts on when workers enter or exit a certain location.

Sclafani said that the technology would correspond with the route schedule inspectors receive at the beginning of each shift. A supervisor can sit at any computer with Internet and look up the location of his unit's workers at that moment. The supervisor also can follow them from inspection to inspection or look at past routes to see whether or not they correspond to the schedule they were given. No one can access the information without the correct username and password.

The department publicly announced the plan Aug. 28 and began implementing it two days later.

Corso said the city should have provided the union with more information than it did and might file a lawsuit over the tracking.

Although the union knew the department had been considering the program for a while, the inspectors did not receive word of its implementation until the day before the public announcement -- three days before the city started using the software with its first 10 workers. The union did not know who those 10 workers were.

To date, Corso says he has not received documentation from the department about how the software works and what the actual plans entail. He said he had two face-to-face meetings with city officials, with few results.

Sclafani said that the union was "well-informed as to the particulars of the program."

If Local 211 does not receive adequate documentation "in the very near future," Corso said that the union would take legal action, a process that starts with the federal Labor Relations Board.

The union, Corso said, wants to ensure that the workers are not tracked past designated work hours, especially since a given inspection does not have a specific ending time. There is, for example, no set time for an inspector to go on lunch break. Because workers must keep their phones on 24 hours a day for emergency purposes, Corso is also concerned the software could track the inspectors after working hours. A sales representative from Telenav said turning off cell phones deactivates the tracking device.

Sclafani said that the technology was activated and de-activated according to the inspectors' schedules. "The software is sophisticated enough where we're only tracking them on duty," he said.

Corso dismissed the tracking program as unnecessary since the Buildings Department has people ensuring that workers are on site, including unit supervisors and the Department of Investigations. People who think it is the "norm" for inspectors to avoid certain stops on their scheduled route "just don't know the system," he said.

The tracking system could do more than upset current workers, Corso said. He worries that it will deter people becoming inspectors, a sobering prospect for an agency that already has a hard time recruiting new people

The inspectors' starting salary of $49,000, said Corso, is less than they could receive in the private sector. The idea of being tracked on the job, said Corso, would present "another stumbling block."

A Heartbeat Away -- But What is the Public Advocate?

Do you know what the public advocate does and that he or she is next in line to succeed the mayor? With New Yorkers set to vote in Tuesday's primary for many city offices, including public advocate, NY1 surveyed New Yorkers and found that most respondents not only did not know who the public advocate is or what the public advocate does, but also had no idea who is running for the office. With that in mind, here's a short primer on the origin and role of this official and the continuing discussion about the utility of this position.

When Did New York City Even Get a Public Advocate?

The position of public advocate originated in 1831 way back when the city was still five separate boroughs, according to a 1998 New York Law School Law Review article co-written by Laurel Eisner and former Public Advocate Mark Green, who is seeking the office again. It was not called the public advocate then, but even as president of the Board of Alderman -- a legislative body representing the borough of New York and portions of the Bronx -- the position was next in line to the mayor. This job was converted into that of City Council president in 1936 -- still a heartbeat away from the mayor in the event of vacancy, disability or other absence from office and empowered to preside over the Council.

The council president had a very limited role in government. During the 1975 charter revision debate, according to Green's article, it was noted that, although the office had no real administrative authority over the delivery of city services, was not a member of the executive branch and had a very narrow role in the council, it served an important function as a "critic at large." After debating whether to eliminate the office -- the first of many conversations about its role and utility of the office -- the 1975 commission instead decided to empower the council president through "a new, quasi-ombudsman role." The term ombudsperson derives from the Swedish word for "go between" or someone who would "protect individuals against the excesses of bureaucracy."

Despite these new ombudsperson powers, the council presidency still was pretty limited in its capacity -- lacking the ability to pursue individual complaints and the enforcement tools to ensure it could actually, not just theoretically, oversee or review city agencies. With this as a backdrop, the 1989 charter revision commission again revisited the issue of the role of the council president. Some commission members proposed eliminating the office, some said keep it, and some presented a new option that is still being debated until this day -- creating an appointed ombudsperson position.

Yet again the council president's role was saved from the hatchet -- this time because Commission Chairman Fredrick A.O. Schwarz argued that the role brought balance to city government by "concentrating on the service implications of the programs" implemented by the mayor.

The 1989 charter commission gave the office new responsibilities that created a bit of a several-headed monster -- one part legislator as presiding officer of the council, one part executive as first in line to succeed to the mayoralty, one part "charter cop" through the ombudsperson role and one part pension trustee for the city's Employees' Retirement System. It also gave the office power to appoint a member of the City Planning Commission, among other appointment responsibilities.

Today, the public advocate's legislative role allows him or her to be an ex officio member of all council committees and to introduce legislation, but not to vote. The ombudsperson role, which was substantially bolstered in 1989, empowers the public advocate to address individual grievances, deal with citywide problems, evaluate the performance of city agencies and "monitor public information service complaints of city agencies."

Despite the substantial increase in the council president's authority, only four years later in 1993, legislation was proposed in the city council to abolish the office of council president. This idea was again rejected in favor of simply changing the name of the office to public advocate to "reflect its charter roles and to dispel the impression that the holder exercised a predominant role in the City Council."

Fast forward to 2009, a municipal election year, and the discussion continues about keeping New York's public advocate. While the candidates vying to be the next public advocate give campaign speeches about what they would do to bolster the office's visibility and authority, at the other end of the spectrum Councilmember Simcha Felder from Brooklyn introduced a bill and issued a report in July 2009 -- proposing to get rid of the office altogether. "It is clear to me that given the services provided by the city's 59 community boards, five borough presidents, and numerous city, state, and federal elected officials, the office of the public advocate could easily be eliminated without a loss of service to city residents," Felder said. Felder's bill is currently pending in the Council's Governmental Operations Committee awaiting a hearing.

Other Places Have Ombudspersons Too

While electing a city ombudsperson may be unique to New York City, the tradition of a public official to empower ordinary citizens, especially those who have been marginalized, originated in the United States in Jamestown, New York. Many other cities and states have this function within their government structure. Portland, Ore., describes its ombudsperson, who is appointed by the city auditor and therefore independent from the mayor and the city council, as being able to assist the public with their complaints and concerns and promote higher standards of services and efficiency.

In Detroit the city ombudsperson is appointed by the city council, but is meant to be an independent government official to respond to citizen complaints against city agencies and government departments. Detroit's ombudsperson holds subpoena power so can retrieve documents and records necessary to conduct investigations -- a power that New York City's public advocate lacks. The current office holder, Durene Brown, claims success for being the first city official to change state law in Detroit -- passing a measure to include libraries as drug-free zones.

Other cities have appointed ombudspersons who focus on addressing complaints in specific areas, like police and law enforcement or senior citizen services, as is the case in Boise and Minneapolis, respectively. Finally, Los Angeles has an ombudsperson office that boasts ombudspersons to seven different city agencies, ranging from the Sheriff's Department to the Department of Social Services.

A Public Advocate's Perspective on the Matter

New York's current public advocate, Betsy Gotbaum, who has been in the office since 2001, said that although people are unfamiliar with the office and it has few resources -- it has a budget that is only "one two hundredth of 1 percent of the total city budget" -- she believes it helps thousands of everyday New Yorkers with their problems. In particular, she said, her office has focused on "improving services for often ignored populations."

Gotbaum disagreed that the services her office provides duplicates other services, citing the many calls the office receives as referrals from the city's 311 non-emergency hotline. She would like to se the 311 include a "direct link" to her office.

Moreover, her office has been able to help many citywide constituents by using a sophisticated computer-based tracking system that allows her and her staff to troubleshoot individual problems while tracking trends that may indicate citywide issues.

In addition, Gotbaum's policy staff, alone or in partnership with relevant advocacy groups, conducts research and issues reports spotlighting problems. These may or may not be accompanied by a press conference depending on whether the issue is something that her office believes the local media will cover. Because of "institutional limitations" and a difficult-to-engage press, Gotbaum said it has been difficult to get attention for the issues she believes are important. Like Gotbaum and the council presidents/public advocates before her, the next public advocate will have to learn to navigate these obstacles in order to be successful.

On Tuesday, many New York City voters may go to their poll sites and wonder who they should select as Public Advocate, why does it matter and whether they believe this office serves an important function. These are all important issues to consider on Primary Day and when the next charter revision commission or local legislation raises these questions again.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel and Andrea Senteno is the program associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.The 63rd Senator

Photo by Edward Reed for nyc.gov

Mayor Bloomberg Testifies in Albany Before the State Assembly Ways and Means Committee and Senate Finance Committee, January 2009

Some legislators call him the 63rd senator or the 151st assemblyman. "His vote has much more impact than that of this lone senator," said Sen. Bill Perkins.

Perkins was referring to New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Whether it springs from his generous sponsoring of Senate Republicans, the weight his opinion carries with the public or the spite some lawmakers feel toward him, Bloomberg has the ability to drastically affect the direction of discourse in Albany.

With so many city issues in the hands of the state legislature, Bloomberg has made his influence felt, assisted by the staff of his Albany office as well as his deputy mayors. This year, though, Bloomberg seems to have stepped back to let his surrogates speak for him, in an evident effort to make the debate less about him and more about the issues. He reduced his combative moments in the capital and focused on the big fight-- renewing mayoral control of schools.

Supporters say he learned from the debacle of his 2008 push for congestion pricing, which ended in defeat for the mayor amid a chorus of verbal attacks from the legislature featuring such epithets as "elitist," "out of touch," and "bully!"

This year, despite the will-they-or-won't-they drama over the Senate's vote on mayoral control of city schools and the ugly spats that took place between the mayor and a group of Senate Democrats, Bloomberg won some important battles with the legislature.

"I don't think the mayor has learned anything, except that he shouldn't speak for himself or come up to Albany," said Sen. Kevin Parker, one of the mayor's harshest critics. "He thinks he is better than us and he can't hide his contempt for us at all, so he tried a different tactic."

Authority Over Authorities

Photo from wikicommons

George Washington bridge is managed by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which would be affected by the proposed Public Authorities Reform Act of 2009

With the legislature out of session, Bloomberg is still affecting the fate of legislation. He is currently wielding his influence to pressure Gov. David Paterson to veto the Public Authorities Reform Act of 2009.

The bill is designed to make public authorities such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the Empire State Development Corp. more efficient, less subject to cronyism and more accountable, and to reduce the influence of lobbyists and politicians. The bill would create an independent budget office that can investigate authorities and monitor their spending. It would also have the state comptroller review contracts awarded by authorities that are worth more than $1 million.

The bill took shape over a period of years, put together as a result of hearings, debates and public outcry. It has been praised by the media, political experts, legislators and good government groups alike. Some observers joked the bill was one of the few good pieces of legislation the Senate passed this year.

Supporters of the bill say only two people seem to have any real problems with the measure -- Gov. David Paterson and Mayor Michael Bloomberg. And they say Paterson's objections only surfaced in recent weeks.

Bloomberg has argued the bill would hurt development projects, because it mandates that authorities must sell any land they own at the market rate. The Paterson administration has objected to the provision that would mandate the state comptroller review contracts worth more than $1 million, saying it would overburden the comptroller.

Sen. Liz Krueger, a co-sponsor of the bill, said that she finds some of the points brought up by Bloomberg and Paterson perfectly "reasonable," but still thinks "the governor should sign the bill into law." Krueger and other supporters of the bill believe a good course of action would be to address concerns about the bill by passing chapter amendments after the bill becomes law.

Making a Fuss

Krueger said neither the governor's staff or the mayor's Albany lobbyists approached her with their concerns prior to the bill's passage.

"They didn't raise them before we took a vote. I never heard opposition from the city. So I am confused, because they have brought lots of things to my attention in the past. The mayor is not a shy man."

Krueger speculates that perhaps Bloomberg's staff was focused on mayoral control and not the authorities.

Photo from nyc.gov

Mayor Bloomberg with Assembly Leader Sheldon Silver

Michelle Goldstein, the director of the mayor's office of state legislative affairs, said the city has long made its objections to parts of the bill known. "The city's opposition to particular provisions in this bill is not new and is a matter of public record. As currently written, this legislation would negatively impact the city's ability to pursue its economic development goals and actually reduces authorities' accountability."

In 2008, Bloomberg spokesperson Farrell Sklerov was quoted in the New York Times as saying, "The city has serious concerns that this proposal would ultimately reduce public accountability and hamper economic development."

Bloomberg aides say a number of legislators want to distract attention from the real issues by trying to make the story about the mayor and his personality.

For their part, some senators think that Bloomberg wanted to avoid an ugly battle with the Senate over the public authorities so instead focused his efforts on the relatively weak Paterson. They say that Bloomberg represents one of Paterson's few remaining allies and a powerful one at that. While these senators originally thought Paterson would sign the bill as a good government measure, they see the governor as having changed course only to keep himself in Bloomberg's good graces.

"Without a doubt there is no other influence that is significant other than the mayor's," said Perkins. "When has something this clearly good been stopped if not for purely selfish reasons?"

Brodsky agrees that Bloomberg's influence is more than apparent. "It is a matter of public record that [Bloomberg] is doing this. He is not doing this in a subtle way. It is all about power," said Brodsky.

Parker, however, says he isn't sure Paterson's stance is due to Bloomberg. "The governor is capable of making his own mistakes," he said.

It is still unclear what the governor will do, but the Bloomberg administration thinks a compromise could be reached easily if all sides sat down to talk.

Getting What He Wants

Compromise seems to have become a part of Bloomberg's Albany routine since his unyielding push for congestion pricing failed in Albany last year. Bloomberg made the fight for congestion pricing personal. He demanded things of legislators both publicly and privately and refused to compromise.

Following that defeat, Bloomberg has attempted to remove himself from the argument and instead focus on the issues with the help of grass roots movements and other surrogates. And this year Bloomberg basically won his biggest battles.

"In the last session we worked with the state legislature to reauthorize mayoral control of schools and approve the city's revenue package," said Goldstein. "We are hopeful that going forward we can work with the governor and the legislature on critical issues such as the creation of a Tier 5 pension plan for new employees."

Bloomberg has an interesting array of tools to help him get what he wants in Albany. Perhaps the most useful one is his wealth. For years Bloomberg has donated heavily to state Republicans, and the change in the control of the Senate hasn't stopped his generosity. His largesse has probably helped him keep Senate Republicans as a supportive voting bloc.

Bloomberg's relationship with Republicans can be a liability as well though. Some Democrats say that by supporting Republicans from rural districts Bloomberg funds people who have propagated the upstate-downstate divide and villainized New York City. As one source put it, "From a practical standpoint, it might not be the wisest investment for the mayor to keep lavishing donations on a minority conference that is openly hostile to the best interests of New York City."

On the Scene

Bloomberg's Office of State Legislative Affairs keeps him connected to the capital. New York is the only city that has a full time lobbying staff at the Capitol. The office is staffed with a director, an assistant director and four legislative liaisons.

The office circulates position papers, gives legislators information about how various measures might affect the city, and negotiates and participates in the creation of legislation. They also act as ears for Bloomberg to gauge how legislators are reacting to proposals.

Deputy Mayors Kevin Sheekey and Dennis Walcott have spent time in Albany lobbying for the mayor's big issues. This year Bloomberg visited Albany twice.

The Battles of 2009

This year started with the city facing major funding cuts in the state budget. Paterson proposed cutting millions of dollars of Aid and Incentives for Municipalities funding to New York City. Large cuts to education were also proposed. But the state restored the aid to municipalities, and the cuts to education were largely patched by federal stimulus money. Despite Bloomberg's contentious relationship with Democratic members of the Senate, the new Democratic majority and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver may well have helped Bloomberg stave off cuts. The Democratic leadership is mostly based in the city and did not want to see jobs lost across the city.

Then came the battle over the MTA rescue plan. While Bloomberg supported charging drivers for entering Manhattan -- after all he himself had proposed another version of it in his PlaNYC2030 -- the mayor was not publicly vocal about it. Many senators from the outer boroughs opposed the Ravitch plan, which would have put tolls on East River Bridges, and derailed it.

Some advocates on the other side complained that Bloomberg was absent from the debate. "You couldn't find the mayor saying anything about the MTA situation," said one senator, adding, "Maybe he was advised to stay quiet."

In the end, the legislature passed a watered-down plan that staved off high fare increases for straphangers but did not include bridge tolls. It was a defeat for Bloomberg, but because he had not been as out-front on the issue as he was on congestion pricing, it was a relatively quiet one.

School Fight

While the mayor's fight to retain control of schools got off to a shaky start partly because of legislators' antipathy toward schools Chancellor Joel Klein, things quickly turned around. Bloomberg had assistance in spreading his message from Learn NY, a pro-mayoral control group to which the mayor has denied ties but which received significant funding from Bloomberg's pal Bill Gates. This helped shape the image of grassroots support for mayoral control. He also had the megaphone provided him by the New York Post, which proudly led "the campaign" to renew mayoral control. Micah Lasher was hired on as the head lobbyist for the Department of Education.

Silver, who has butted heads with Bloomberg in the past, reached a deal to renew mayoral control through an Assembly bill that contained a few new measures designed to address criticism. There is quite a bit of speculation about how the two mended fences, but people who know are not talking.

When it came time for the Senate to act, things still seemed to be coming together for the mayor. Even while some legislators demanded a major overhaul of the system, negotiations between then Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith and Bloomberg's office seemed to be proceeding smoothly and the Senate seemed likely to pass a bill very similar to the Assembly's.

But then came the coup that plunged the Senate into deadlock. When Sen. John Sampson became leader of the Democratic conference, supporters of mayoral control began to worry. Sampson was an outspoken critic of mayoral control as it existed.

It wasn't until the city sales tax was voted down during a legally questionable session that it became clear what a hostile crowd Bloomberg would now face on mayoral control. Sources say senator blocked the tax increase that would allow the city to balance its budget simply to send a message to Bloomberg and to retain some leverage in negotiations over mayoral control.

Once the coup ended, the Senate did approve the hike in the city's sale tax. But there still was no agreement on mayoral control.Parker brought his Better Schools Act, which would have drastically curtailed the mayor's authority, to a vote. It failed but the bill's very existence was seen as an slap in the face to Bloomberg.

Then things really got ugly.

Some Democratic senators openly taunted Bloomberg, and, when asked at a press conference whether he would negotiate with the Senate, Bloomberg said he would not be Neville Chamberlain. Later, when asked if he was comparing the senators to Nazis, Bloomberg responded, "I certainly did." A spokesperson later claimed that Bloomberg had misheard the question.

A few days later, Sen. Pedro Espada told the press he would soon be having "'Pollo a la Bloomberg." Perkins accused the mayor of "treating us like we're some people on his plantation."

A number of senators seem to revel in their contempt for Bloomberg like children trying to impress each other by taunting the neighborhood dog.

It wasn't much later that a deal was announced, having been negotiated by other senators. It gave the Senate some of the concessions it was looking for but left mayoral control largely intact. Bloomberg had his control of schools renewed, and some of the more outspoken senators had had their chance to openly bash the mayor.

In a way, both sides got what they wanted.

Even though Bloomberg succeeded, the episode, along with Bloomberg's previous setbacks in the capital, made it clear that, in Albany, the mayor does not enjoy the seemingly boundless power that he has in the city. Up the Hudson, he still finds himself subject to the whims of the legislature. If Bloomberg wins a third term this year he will likely have to adjust his approach to Albany yet again -- as the 2010 elections may leave him with an entirely different playing field.

Getting on the Ballot in Other Cities

In contrast to New York, most U.S. cities have nonpartisan elections for local office. But every municipality has its own quirks when it comes to how candidates get on a ballot.

To learn about New York's ballot access and the blood sport of ballot bumping, read New York's Election Labyrinth.

Some cities, according to Richard Winger, an expert on ballot access and the publisher of Ballot Access News, decide election laws for themselves. Others, like Newark, stick with their state's prescriptions for operating elections.

Winger says that generally the difficulty of getting on the ballot depends on whether the election system is partisan or nonpartisan. The fairer system, in Winger's view, is a nonpartisan one. He said he is "overwhelmingly in favor of a filing fee," instead of petition requirements, as the way for candidates to get on a ballot.

Party Politics

Philadelphia's ballot access laws are similar to New York's. The City of Brotherly Love has a closed primary system that allows only registered party members to run in the primary election. Candidates running as Democrats or Republicans for citywide office need to collect 1,000 signatures from members of their party within three weeks.

Independent candidates face a far higher hurdle. The number of signatures they have to collect must equal at least 2 percent of the winning candidate's vote total in the last election in the district where the candidate is running. For a citywide candidate -- where the "district" is the entire city -- independents need at least four times as many signatures as people running in a party primary. They have a few months to come up with all those names and can get people from any party to sign their petitions.

Like New York, petition challenges from rival candidates, which have to be submitted within the week after the filing deadline, are common in Philadelphia. However, according to Deputy City Commissioner Fred Voigt, candidates can amend petitions after a challenge has been brought, a process that New York does not have. For example, if an address on the petition is incorrect, the candidate can correct it, and the signature would be valid.

Candidates in Newark also must file petitions to get on a ballot and have about two and a half months to collect the required number of signatures. That number varies, depending on the election cycle. In the 2006 Newark mayoral race, candidates needed close to 1,200 signatures. In a New York mayoral race, candidates need 7,500 signatures. If you look at the two cities' requirements in proportion to its overall population, Newark office seekers have a tougher time. The total number of signatures Newark candidates need equals about 0.5 percent of its population, while New York candidates need signatures that amount to about 0.1 percent of the city's population.

Candidates file their petitions 54 days before an election. Rival candidates can challenge petitions, but like Philadelphia, candidates can amend "defective" petitions as long as they do not add signatures.

Officially Non-partisan

Chicago also requires petitions to get on a ballot. In its nonpartisan elections, candidates have 90 days to gather signatures. For the citywide offices of mayor, city clerk and city treasurer, office seekers need to get 12,500 valid voter signatures. Aldermen -- Chicago's City Council members -- need to collect signatures equal to at least 2 percent of the total vote cast in the last general election in their ward. For example, in 2007, candidates in ward 22 needed 67 signatures, while in ward 23, they had to have 306.

The procedures in Los Angeles and San Francisco differ markedly from those in New York. The State Constitution of California requires municipal and county elections to be nonpartisan, and candidates in both cities have 25 days to collect the obligatory number of signatures. Los Angeles candidates can pay a filing fee to reduce the number of signatures needed, while in San Francisco they can pay a fee to avoid having to collect any at all.

The filing fee is 2 percent of the salary of the office sought. So a candidate for mayor -- a job paying $252,886 a year -- can pay $5,058 to get on the ballot or he or she can collect 10,116 petition signatures, which is more than the required amount needed in the much larger city of New York. A candidate also can use a combination of petitions and fees, with each signature reducing the fee by 50 cents. There are no petition challenges from rival candidates, and the San Francisco Department of Elections verifies each signature.

Candidates in Los Angeles also have the option of paying a fee to reduce the amount of petitions collected, although they all must submit some signatures. Candidates for office can pay a $300 filing fee and submit between 500 and 1,000 signatures. Office seekers who do not want to pay a fee must submit between 1,000 and 2,000 signatures to the City Clerk. There are no petition challenges from rival candidates.

Understanding the Labyrinth: New York's Ballot Access Laws

photo (cc) Taekwonweirdo

Just how hard is it to get on New York's ballot? Go here to Play Bump the Birds, Gotham Gazette's new ballot access game and find out. Are you smart enough to get on the ballot - and tough enough to stay there?

If you have attended a street fair, shopped at a green market or even walked along a city street, you have undoubtedly seen them smiling, holding clipboards, asking for a moment of your time to please sign their petition. All three citywide offices, including mayor, the five borough presidencies and all 51 City Council seats are officially up for grabs this year, and candidates have been busy collecting signatures for petitions needed to get on the ballot.

Only 10 months ago, New Yorkers expected a far more frenzied political landscape, since all the citywide officials, four of the borough presidents and 32 City Council members were about to be forced from their office by term limits. Then, in October, the City Council and the mayor decided to give themselves more time in office, extending the number of consecutive terms they could serve from two to three. Many candidates were waiting, hoping to run for the open seats of council members who would have been term limited, but now only eight council districts will see completely open races with the incumbent not running for re-election. Most incumbent council members will be running to represent their districts for one more term, as will all the borough presidents -- shrinking the pool of choices for voters. Although most of the current office holders face challengers, the incumbents will go into those contests with a clear advantage.

To learn about getting on the ballot read "Getting on the Ballot in Other Cities."

Another factor has historically narrowed the pool of competition even further: New York's cumbersome ballot requirements. New York is one of a handful of states that still requires all candidates -- incumbents and challengers -- to file petitions with voter signatures to secure a place on the ballot. Those petitions have to comply with a complicated list of requirements for the signatures to be considered valid.

This has turned the whole petition process into a political blood sport. Candidates with experienced election lawyers can bump many of their rivals off the ballot by challenging the validity of their opponents' petition signatures, disqualifying the signatures from the candidates' total signature count. These errors can include unclear handwriting, or the absence of a zip code or borough.

The lengthy and complicated rules have created a system that hinders healthy competition, according to candidates, voters, good government groups and even some election lawyers, who make their living by knowing these intricate ballot access laws. They use them to help candidates stay on the ballot and even kick off the competition.

A Guide to New York's Ballot Access Laws

New York's notoriously cumbersome election laws were created in the late 1800s to democratize the election process. Up until then, party leaders controlled which candidates were placed on the ballot. However, today's petitioning requirements ensure that only those candidates with huge campaign war chests or party backing have the wherewithal to get on the ballot -- and stay there.

Here's a nuts and bolts synopsis of New York's ballot access process from the New York City perspective:

In order to get on the New York City primary election ballot this year, candidates could begin collecting signatures for their designating petitions on June 9 -- 37 days before the last day to turn in designating petitions for the primary election

The law is very specific about how many signatures candidates must collect. They have to get 5 percent of the enrolled voters of the political party in the political unit covered by the office -- council district, borough or the entire city -- or the specific numbers enumerated in the state's Election Law, whichever is less. For a candidate for City Council, that number is 900 signatures, but as a cushion against petition challenges, the rule of thumb is to obtain at least three times the legal minimum.

The candidates also must figure out is who is eligible to sign the petitions and who can collect the signatures. While only registered voters who are members of the candidate's political party and reside in the district in question can sign the petition, any registered voter who is a member of the candidate's political party and lives in New York City can collect signatures. Voters are allowed to sign just one petition per office.

The candidate has approximately five weeks to collect all of the requisite signatures and file his or her designating petitions with the main city Board of Elections office between July 13 and 16, which complies with the state law requirement that designating petitions be filed between the tenth Monday and the ninth Thursday preceding the primary election.

That done, the challenge portion of the petitioning process begins. According to the board's rules, it conducts a prima facie "review [of] each cover sheet and petition to ensure compliance with the New York State Election Law." This marks the first round of challenges to the candidate's petition -- but definitely not the last. The law allows any voter registered who can vote for the candidate to file written objections with the Board of Elections challenging that candidate's designating petitions. Those challenges must be made within three days of the filing of the petitions.

Once challenges are filed, the board holds hearings to assess the validity of the challenges and issues a determination. In order to appeal the board's decision a person must commence an action in state Supreme Court, the lowest level court in New York's court system, "within 14 days after the last day to file a petition or within three business days after the board makes a determination regarding the invalidity of such petitions, whichever is later."

If the appeal involves a determination about whether a candidate's name will appear on the ballot or a voting machine, the Supreme Court, if possible, is supposed to issue a final order at least five weeks before the day of the election. Candidates can appeal such decisions.

A Ballot Access Case Study

The Feb. 24 nonpartisan special elections for City Council held earlier this year offer a classic example of how the state's ballot access laws can cause major headaches for voters and election officials. Running for the Staten Island seat vacated by now U.S. Rep. Michael McMahon, candidate John Tabacco was a target of aggressive challenges by the current council member, then opponent, Kenneth Mitchell.

Tabacco faced two separate challenges. Like all candidates running in nonpartisan elections, Tabacco had to select a symbol for his "party." He made the mistake of selecting a five-pointed star, the official ballot sign of the New York State Democratic Party, which contributed to his unstable ballot status.

The other challenge involved the board assessing the validity of his signatures. The board re-examined some of Tabacco's petition signatures and decided that many of the signatures he collected were invalid; therefore his total collection failed to meet the number needed to appear on the ballot. After much legal wrangling, the day before the election, the Appellate Division restored his name to the ballot.

In preparation for the election, the board had already sent the voting machines to the poll sites, without Tabacco's name listed. With the legal decision coming less than 24 hours before the polls were set to open, the board had to swiftly shift to conducting the election on paper.

These last minute changes can be costly to candidates and taxpayers alike. In Tabacco's case, he said the petition challenges claimed 75 percent of his time during the special election in February, leaving him little to no opportunity to fundraise and campaign. He eventually lost to Mitchell, coming in fourth.

Of the total $179,983 he spent on the campaign, Tabacco said, approximately 28 percent went for election lawyers, political consultants and campaign volunteers related to meeting the petition requirement and defending the signatures in the legal process. "It's a completely outrageous, disgusting process," Tabacco said

The lengthy back and forth that can sometimes happen with ballot disputes, does not just cost the candidates. In District 49, the expense of all the paper ballots with the last-minute changes was eventually passed on to taxpayers. After including the cost of transporting the unused machines to and from the poll sites, staff to coordinate the move, and the printing of paper ballots for all the voters, the Board of Elections spent $132,564 on this election. Over $50,000 of that went for paper ballots.

Insiders' Perspectives on Ballot Access

Another candidate who ran in a Feb. 24 special election, George Dixon, a long-time resident of East Elmhurst and a former member of Community Board 3, has a slightly different take than Tabacco about the petitioning process -- probably because he had an election lawyer and didn't spend as much time in court as Tabacco.

"The upside is that you get someone out there and recognized in the community. The downside is that there are various reasons why a signature may not be considered valid," he said, noting that signatures can be removed if a piece of required information is missing, like the date or the county of the voter. "When you challenge a community of signatures, you're not challenging the candidate, you're challenging the voter," Dixon said.

Jerry Goldfeder, an election lawyer at Stroock, Stroock and Lavan LLP who worked on Julissa Ferreras' campaign against Dixon and other candidates in the Queens special election, said that there are better systems than petitioning for getting a candidate on the ballot. "I've been a long-time advocate of abolishing the requirement that one needs petitions to get on the ballot," Goldfeder says. "There are other ways to show community support to become a candidate, such as the number of donations, or perhaps a filing fee."

Election lawyer Henry Berger, agreed. "The petitions' challenges in New York are one of the tactics used to discourage people from running for office," he said.

Some claim the city's nonpartisan special elections present even more burdensome signature requirements than regular elections because candidates have to rush to get the required number of signatures in a much shorter time period. If challenged, the time period to appeal and stay on the ballot is much shorter as well.

Reforming New York's Ballot Access Law

Proponents for changing the ballot access laws argue that, under the current system, candidates are required to collect too many signatures with too little time, a task that can be difficult if you do not have the support and resources of a political party behind you. They say that, in effect, these laws diminish voter choice by only leaving one or two names on a ballot and excluding community members who might be credible candidates, but are unable to raise the funds necessary to withstand aggressive ballot-bumping. Candidates whose signatures are challenged, have to spend time in hearings with the Board of Elections and in the courts, taking precious time away from increasing their name recognition and campaigning. Perhaps more importantly, it drains financial resources.

One recommendation for reforming the state's labyrinth ballot access laws calls for reducing the number of signature candidates needed to appear on the ballot. Good government advocates also argue that other broad changes to elections can create a more level playing field for new candidates. Proposals include nonpartisan elections, ranked voting, independent redistricting and public campaign financing. Getting the access laws changed, though, poses a real challenge. Whatever they may cost voters and the public, these laws also benefit incumbents who want to remain in office and stymie competitive elections. Given that, it's no wonder that these laws have not been reformed.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel and Andrea Senteno is the program associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Additional reporting for this article was provided by Alex Kane, an intern for Gotham Gazette.

Where Is New York's Lieutenant Governor?

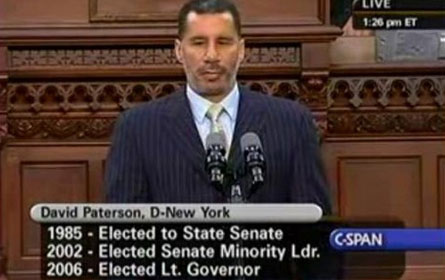

On March 17, 2008 when New Yorkers and the news media were focused on the resignation of Gov. Eliot Spitzer, few, and probably only hard-core political wonks, considered the effect Spitzer's resignation would have on the office of lieutenant governor since the then lieutenant governor, David Paterson, was about to become governor.

Now, over a year later, the lieutenant governor position remains vacant. Questions about the lieutenant governor's post have gained far more prominence given the very slim Democratic majority in the Senate. New York law allows the temporary president of the Senate, who is also the majority leader, to perform all of the duties of the lieutenant governor during the vacancy or inability, and Temporary President of the Senate and Majority Leader Malcolm Smith no doubt wishes that there were a Democratic lieutenant governor to give his Democratic caucus a much-needed tie-breaking vote. So does the temporary president of the senate get to vote twice if needed to break a tie vote? For obvious reasons Smith would love for the answer to that question to be a resounding YES.

The Conundrum of the Lieutenant Governor Vacancy

Unfortunately for Smith, however, while the New York State constitution empowers the lieutenant governor to act as the president of the Senate and also cast votes in that body, he will not be getting that extra Senate vote any time soon. That is because, the law does not specifically allow for the office to be permanently filled. Even worse, the law is about as confusing as can be with respect to how long the temporary president of the Senate fills this new dual role and how having two posts affects the temporary president's role as leader of the Senate chamber.

One would think that the current situation is only confusing because the situation is so unusual. Quite the contrary is the case, however, because lieutenant governor vacancies and their political consequence are old hat. At this point in the state's history, on nine separate occasions, a governor vacated that office and the lieutenant governor moved in to fill the vacancy.

This begs the question then: Why doesn't New York have a clearer and more concrete process for filling a vacancy in the office of lieutenant governor? Political realities of Albany politics aside, this convoluted process must be due at least in part to the state's complex and lengthy constitutional amendment process.

Passing a constitutional amendment in New York is a multi-step and multi-year process. In layman's terms, first the legislature has to introduce a bill proposing a constitutional amendment. Then that bill has to be reviewed by the state's attorney general to determine its effect on other sections of the constitution. After the attorney general approves the bill, then the Assembly and Senate have to pass the bill by majority vote before the end of the two-year legislative session. At the start of the new two-year legislative session after the succeeding general election, the bill passed during the previous session must age for three months before the legislature can vote on the constitutional amendment again. Assuming passage at this stage, the constitutional amendment must finally be approved by the voters.

In practice, this timeline means that even if legislators could decide on which process for filling the lieutenant governor vacancy they wanted to adopt for New York at this time, they would have to vote on the bill before the end of June 2010 and then again in 2010 or 2011 after the general election before putting it to the voters.

What Other States Do

If the Legislature takes the timing constraints seriously and gets down to the details, there are a few procedural options for how to fill this vacancy. According to a new report Filling Vacancies in the Office of Lieutenant Governor, published by Citizens Union, the nonprofit advocacy arm of Citizens Union Foundation, Gotham Gazette's publisher, 30 states specifically delineate a process for filling lieutenant governor vacancies.

Among those that have a process, the most common procedure - used by 14 states - is for the governor to appoint someone to the post who may or not be subject to some form of legislative confirmation. Ten of these 14 states, including California, Florida and Maryland, allow the governor to fill the appointment with a confirmation by a majority of both houses of the legislature. But some states like New Mexico, which amended its law in 2008, require that only the Senate confirm the governor's appointment.

Another seven states, such as Connecticut, Hawaii, Pennsylvania and South Carolina, either allow the temporary president of the Senate to automatically fill the vacancy, or make the temporary president serve in specifically limited capacities - like New York's process. At the other end of this spectrum, New York could adopt Alabama and New Jersey's practice of holding a special election to select the next lieutenant governor. The final option, which is used by two states - Rhode Island and Texas -- may be more in line with New York's tradition of appointing commissions or task forces to study issues. These states create a special senate committee that elects a replacement.

Currently pending in the New York's Legislature are at least six bills that adopt various forms of the processes for filling lieutenant governor vacancies used nationwide. The diversity of the proposals presents the Legislature with a variety of options, but in order to institute any change the governor and Legislature are going to have to act soon.

What Should New York Do and How to Get There

As any casual follower of Albany politics knows, change is slow, or at worst unlikely. So does that mean that New Yorkers are likely to be without full representation in the state capital in the form of a lieutenant governor? Unfortunately, the answer is yes. This is not only due to the potential for Albany inaction on this issue, but also because the timetable for passing a constitutional amendment means the legislature does not have enough time to act before New Yorkers elect a governor and lieutenant governor in 2010.

Even though it may be too late to change the current process for filling lieutenant governor vacancies before 2010, it does not mean the elected officials in Albany get a pass this time or that the fire is out and therefore Albany should do nothing. New Yorkers deserve full representation in Albany at all times, especially since the lieutenant governor is one of only four statewide elective offices, so elected officials have a responsibility to change the law to avoid this problem in the future - when, given New York's history, this ultimately will happen again.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Additional reporting for this article was provided by Jessica Lee, an intern for Citizens Union Foundation.

The Legislature Takes on Election Reform

The new Democratic hold on the State Legislature has made headlines for many things these past few months other than an increase in legislative activity or at least the appearance of one. Last year, good government advocates speculated that if Democrats won the State Senate and broke the decades long party split between the two houses, it would either be a new day in Albany or a test of the party's true commitment to reform.

While the Democrats have yet to receive a glowing review on the way they have handled some state matters, there is some indication that election reform is receiving increased attention. Even though the issue is widely seen as off radar during this economic crisis, there are currently over 50 bills in the Senate to amend election law. The Assembly has over 170 bills. A number of these measures -- some of them small -- could improve elections for New Yorkers.

Changes Big and Small

While it still seems unlikely that New York voters will be able to vote the weekend before an election, register and vote on the same day, or even sign up for an absentee ballot online anytime soon, some election legislation has jumpstarted the discussion. There are at least five different bills in the Senate and Assembly on early voting alone, and more on the implementation of Election Day registration, universal registration (where the government is responsible for keeping a list of eligible voters) and rules to amend the special election process.

Voting advocates have been pushing for changes like these for years. They argue that by making voting more convenient and by increasing opportunity and access to the polls, New York can increase its dismal voter participation record, which remains one of the lowest in the nation. Other states, such as Wisconsin and Minnesota who have programs like Election Day registration and early voting, are among those that boast some of the highest voter participation rates in the country. To remove some of the barriers to voting in New York's primary elections, a bill was introduced to shorten the lead time period for voters to change their party enrollment from the current requirement, which requires voters change party enrollment the previous year.

However, election reform is more than big changes, say voting advocates. It is also about the minor details that can make elections more transparent, accountable and secure. Recently, the Senate passed legislation that would count absentee ballots which were filled out in the correct poll site but at the wrong poll table. A long-held practice in many places, it is rooted in a court decision from 2005 (Panio v. Sunderland) that states being in the "right church, wrong pew" should not disqualify a citizen's ballot. The bill's sponsors also hope this measure would ensure that voters who receive an incorrect affidavit ballot, perhaps due to pollworker error, would still be able to cast a valid vote. It is now in the Assembly election law committee.

This proposed legislation seems to cover every aspect of elections. The bills target a wide range of problems, attempting to address long-standing issues with the state's administration of elections and even party politics.

One bill, for example, aims to require primaries for any special election to fill a vacancy in the State Legislature. Currently party leaders convene to select the official party backed candidate in a special election.

To address problems that have plagued poll site location, one bill would require all poll sites be handicap accessible according to the Americans with Disabilities Act. Another bill attempts to establish that no school serve as a polling place. In contrast, several voting advocates have argued that schools should be closed on Election Day so they can be used without compromising students' safety. And yes, there is legislation for that too.

Making Bills Law

Many have suggested that the good government platform -- including some election issues -- could make some real progress now that Democrats control both the Assembly and Senate. Other advocates, though, are quick to caution that the Democrats' true priorities will take shape as they settle into their fragile and newfound leadership role, and that pushing good government issues could still be an uphill battle.

Once bills pass through the appropriate committees in each house, they have to be voted on by the Assembly and Senate. It is widely speculated that the Assembly approved a number of reform bills in previous years knowing their passage in the State Senate would never come. With one-party control, both houses are likely to reevaluate their agendas, and issues that once sailed through the Assembly could encounter more opposition there. In addition, bills that pass the Election Committee in the Senate could meet a different fate on the Senate floor, especially since Democrats hold such a delicate majority.

A State Senate announcement this month that it would begin hearings across the state on election reform, though, gave advocates some cause for optimism. Sen. Joseph Addabbo, in the prepared statement, said, "We will address election issues with a deliberate approach, with hearings on voter registration, absentee ballots, election day and voting issues, Board of Elections oversight, new voting machines and other related matters."

Voting advocates hope these hearings will offer an opportunity to move the ball forward on many of the issues they have been pushing for. Aimee Allaud, elections specialist for the state League of Women Voters, said the hearings will "bring new opportunities for voters to speak to these issues which affect us every time we vote. New York needs to make additional progress in assisting all eligible voters to exercise the franchise."

Andrea Senteno is Program Associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.

Council Committee Frequency

| MEMBER: | STIPEND: | COMMITTEE: | NUMBER OF MEETINGS SINCE JAN. 06: |

| Eric N. Gioia | $10,000 | Investigations*** | 6 |

| Albert Vann | $4,000 | Community Development* | 7 |

| Inez E. Dickens | $10,000 | Standards and Ethics*** | 7 |

| Maria Baez | $10,000 | State and Federal Leg.*** | 16 |

| Alan J. Gerson | $10,000 | Lower Manhattan Redevelopment | 24 |

| Michael C. Nelson | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 29 |

| James Sanders, Jr.* | $10,000 | Veterans | 31 |

| Letitia James | $10,000 | Contracts | 32 |

| Domenic M. Recchia, Jr. | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 32 |

| Charles Barron | $10,000 | Higher Education | 32 |

| Kendall Stewart | $10,000 | Immigration | 32 |

| Sara M. Gonzalez | $10,000 | Juvenile Justice | 32 |

| Lewis A. Fidler | $10,000 | Youth Services | 34 |

| Darlene Mealy* | $10,000 | Women's Issues | 34 |

| Larry B. Seabrook | $10,000 | Civil Rights | 35 |

| David Yassky | $10,000 | Small Business | 35 |

| Simcha Felder* | $10,000 | Sanitation | 36 |

| Diana Reyna | $10,000 | Rules | 37 |

| Maria del Carmen Arroyo | $10,000 | Aging | 40 |

| G. Oliver Koppell | $10,000 | Mental Health | 41 |

| Gale A. Brewer | $10,000 | Technology in Govern. | 42 |

| Helen D. Foster | $10,000 | Parks and Recreation | 46 |

| Miguel Martinez* | $10,000 | Civil Service and Labor | 47 |

| Thomas White, Jr. | $10,000 | Economic Development | 47 |

| Michael C. Nelson | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 29 |

| Jimmy Vacca* | $10,000 | Fire and Criminal Justice | 49 |

| Joel Rivera | $10,000 | Health | 53 |

| Michael C. Nelson | $10,000 | Waterfronts | 29 |

| Bill de Blasio | $10,000 | General Welfare | 55 |

| James F. Gennaro | $10,000 | Environmental Protection | 55 |

| Helen Sears* | $10,000 | Government Operations | 57 |

| Robert Jackson | $10,000 | Education | 58 |

| Peter F. Vallone Jr. | $10,000 | Public Safety | 61 |

| Leroy G. Comrie Jr. | $10,000 | Consumer Affairs | 62 |

| Erik Martin Dilan | $10,000 | Housing and buildings | 71 |

| John C. Liu | $10,000 | Transportation | 82 |

| Melinda R. Katz | $18,000 | Land Use | 105 |

| David I. Weprin | $18,000 | Finance | 121 |

| * New Committee or New Chair *** Does not have a meeting quota. All other committees must meet every month, besides July and August. As of February, a committee would have been required to meet 31 times. |

|||