Can the Next Attorney General Fix Albany?

Last week, federal agents and investigators from the state attorney general's office raided Senate Majority Leader Pedro Espada's nonprofit, Soundview Health Clinic. The previous day, Attorney General Andrew Cuomo announced that he was filing a civil case against Espada for pilfering $14 million from Soundview. The suit charges that Espada spent hundreds of thousands on sushi, campaign literature and family trips, and even granted himself a multi-million dollar severance package.

Espada's alleged corruption has been Albany lore for years, and he now joins a list of state politicians charged with abusing their office. The attorney general's office is currently investigating Gov. David Paterson. Meanwhile, former Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno waits for sentencing following his conviction on federal corruption charges. To top it off, former Assemblymember Anthony Seminario was recently sentenced to six years on federal corruption charges, and a number of legislators are under federal investigation for their relationships with nonprofits.

Susan Lerner of Common Cause said that Albany faces a "crisis of corruption." So why -- Espada’s case aside -- has the attorney general not brought more corruption cases? Why have federal authorities taken the lead? And what more can, or should, the attorney general do to police Albany?

New Yorkers will almost assuredly elect a new attorney general this year, and already at least five Democrats have lined up to seek the job. So the question of how he or she would confront official corruption has acquired new urgency.

The State’s Top Lawyer

The attorney general has enormous authority. He or she serves as the legal counsel for the state and for state employees facing lawsuits. The office protects the public good and can investigate and file lawsuits in the areas of consumer fraud, civil rights, real estate, environmental protection and internet transactions. It also collects money owed to the state.

The attorney general's office, though, does not have a license to police Albany. The attorney general cannot start a public corruption probe unless it is referred by a head of a state executive agency, the governor or the state legislative ethics board. The attorney general also has little oversight over election law violations unless the governor compels the office to investigate them. The office once had sweeping power to prosecute election law violations, but that ability was ceded to the Board of Elections in the 1970s.

As elected officials –- and politicians -- attorney generals almost inevitably will make political calculations about cases. This can cut both ways. Espada has charged Cuomo’s prosecution of him is politically motivated. Critics of former Attorney General Eliot Spitzer say he did not pursue Albany’s misdeeds as fervently as those of Wall Street because he wanted support of elected officials when he ran for governor.

During a 2004 interview with Gotham Gazette, former attorney general and current City Councilmember Oliver Koppell asked, "How can the lawyer for state officials investigate wrongdoing by those officials?"

Others, including those vying for the office, say they can.

"I don't think it matters who is prosecuting the charges as long as they are brought," said Assemblyman Richard Brodsky, a candidate for attorney general this year. Brodsky added that he thinks a number of the larger corruption cases were prosecuted by the federal authorities simply because they fell under federal jurisdiction.

According to Eric Phillips, spokesman for Nassau County District Attorney Kathleen Rice, another Democratic candidate for attorney general, federal investigations have exposed more corruption in Albany than the attorney general simply because the state official does not have the power to do so. "Despite [the attorney generals'] unique insight and statewide grasp of the landscape and the laws, the legislature has limited their scope and put them in a rather narrow place between local district attorneys and U.S. attorneys,” Phillips said.

That is not to say Cuomo has kept his hands off Albany completely. He ran as the "Sheriff of State Street," promising to deliver Albany from itself. To start out, he created a system where his office screens member items. He created Project Sunlight -- a virtual digest of member items, legislation and campaign contributions -- and has repeatedly called for the power to issue subpoenas in corruption cases.

Only recently, though, with both the Paterson and Espada investigations, has Cuomo truly bared his teeth.

A number of politicians who hope to replace Cuomo have their own ideas of how the office should lead the charge against corruption in Albany. Some Democrats say they believe Cuomo has not been as aggressive as he could have been in hunting down corruption in Albany because he wanted to maintain his political alliances. Those vying to replace Cuomo (assuming, as everyone does, that he will run for governor) have been trying to explain their vision to voters as the race begins to heat up. The first major test will be Democratic Rural Conference straw poll in Niagara Falls on Saturday.

Power to the Attorney General

At the turn of this century, Spitzer rode into town vowing to clean up Wall Street. While Washington turned a blind eye to questionable conduct in the financial industry, Spitzer, with the help of the Martin Act (a piece of New York's General Business Law written in 1921 that allows the attorney general extraordinary powers in fighting financial fraud), was able to build his Sheriff-of-Wall Street reputation.

Sean Coffey, a lawyer best known for recovering millions for the victims of the WorldCom debacle and a Democratic hopeful for attorney general, said he thinks the legislature must grant the attorney general powers equivalent to the Martin Act to police corruption in Albany. "Given the state of the state, the number one mission for the next [attorney general] has to be to fight corruption. For Wall Street we had the Martin Act, and we need that to fight corruption in Albany,” he said

Coffey said he expects that the top priority following the November election will indeed be reform. Coffey said he will work side by side with Cuomo -- if he is elected governor -- to enact reform, but says the attorney general's office will need additional power no matter who is governor. The attorney general "needs the permission of the governor or department heads to initiate an investigation," he said. "I think that has cramped Andrew Cuomo. Let’s give the [attorney general] the tools he needs.”

Phillips said that Rice, "absolutely believes that the attorney general should be unshackled when it comes to these cases, but she also thinks the next [attorney general] should find innovative ways to ensure justice and use the office's existing reach and resources. The next [attorney general] won't necessarily be able to rely on Albany for an increase in jurisdiction, so [Rice] believes the solution should include both expansion and innovation."

Another candidate, the former superintendent of the New York State Insurance Department Eric Dinallo, who is also credited with dusting off the Martin Act for Spitzer, has a six-point plan for getting the job of reform done. Most of it relies on using existing law to better regulate Albany. His major proposal calls for the governor to sign an executive order giving the attorney general jurisdiction over corruption cases involving state departments, agencies and the legislature.

“Mr. Dinallo continues to support Attorney General Andrew Cuomo's call for legislation granting the attorney general primary jurisdiction over public corruption cases, but with the stroke of a pen the governor can, and should, immediately provide the attorney general greater authority," a statement from him says.

Brodsky said he thinks focusing on prosecution will not "change the culture of Albany or affect the rate at which these crimes occur." Instead he thinks the attorney general has to lead efforts to change the culture of Albany and make fighting corruption his or her top priority.

"We need to reform the office again," said Brodsky. "Under Spitzer it went from consumer advocate to Sheriff of Wall Street; we need to reform it again to make the office the base for Albany reform efforts."

Sen. Eric Schneiderman, a Democratic attorney general candidate who has proposed numerous ethics reforms during his time in the Senate, said that he would expand the public integrity unit that looks into political corruption and put one member from it in every local attorney general's office across the state. "There are already plenty of statutes that give the office lots of authority. There are restraints on jurisdiction in certain areas, but the [attorney general] has broad authority over misuse of public funds," said Schneiderman.

Schneiderman said that he has already been leading a change in the culture of Albany, including chairing the Senate committeethat recommended the ouster of Sen. Hiram Monserrate after he was convicted of misdemeanor assault.

An Expanded Role

Representatives of good government groups say they would like to see the attorney general have more oversight. "Anything that would increase oversight is warranted until the legislature can pass ethics legislation with independent oversight," said Lerner.

Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group agrees.

"The problem is that laws of jurisdiction prevent the attorney general from looking at things unless they are invited," Horner said. The Legislative Ethics Commission, which has the job of investigating corruption, is relatively useless, he said. Any cases they investigate would be referred to the attorney general, but Horner says the office does not initiate its own investigations and rarely -- if ever -- looks into possible ethics violations. "The attorney general can't do much about it. It makes a lot of sense to me that someone besides the commission should have oversight," he said.

At the same time, some note that it's not just the powers granted to the attorney general that determine whether corruption gets prosecuted. The attitude and priorities of the office's occupant makes a difference too.

"If there is a will there is a way," said Baruch College Professor Doug Muzzio. "They've got substantial powers to investigate political corruption; we've seen that with Espada and Troopergate."

"There has been reluctance in the past for elected officials to take on the system that got them there," said Horner, adding, "I think Andrew has run as the 'Sheriff of State Street,' and he delivered."

Espada, on the other hand, has alleged that Cuomo's investigation is politically motivated -- a punishment for Espada's role in orchestrating last year's Senate “coup.”

Others have alleged that Cuomo has been eager to go after Espada because federal investigations into the abuse of nonprofits by senators are heating up, and he does not want to look as though he has been sitting on his hands. They say the Espada investigation is a perfect lead in to Cuomo's announcement that he will run for governor.

Still others worry that giving the attorney general more power could lead to political abuse. "Would the consolidation of powers or enhancement lead to an overzealous (attorney general) looking to make a name for himself?" asked Muzzio. "I don't know. It's just a question. It could provide the condition for abuse."

As Big Change in Voting Approaches, Election Board Lacks a Leader

With New York facing the biggest changes in voting in decades, the city Board of Elections, the agency entrusted with making sure everything goes smoothly, has no executive director.

The post has remained vacant since Marcus Cederqvist, the previous occupant, abruptly announced his departure in January and left shortly thereafter. Not only does the board not have a director but it has not revealed a timeframe for or method by which the next person will be selected.

All this comes as the city prepares to abandon its old lever machines and replace them with a new computer-based voting system by next fall's elections for governor, two senators, members of Congress and other political leaders. In the meantime, new technology must be tested and implemented, pollworkers have to be trained, and voters need to be educated.

The situation at the board has alarmed watchdog groups and some public officials. "It's an injustice to the voters of New York, and the taxpayers of New York, to not conduct a meaningful, open public search, and to set out expectations, to have a contract, and to have performance criteria," said Neal Rosenstein, coordinator for the New York Public Interest Research Group.

Secret Search

The executive director oversees the voting operations for New York City. In theory, the appointee is responsible for overseeing poll worker training, voter registration and implementation of new technology and new policies.

It is "a position of great potential impact, and New Yorkers have a right to see that the best possible person is selected to run their election," said Lawrence Norden, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice.

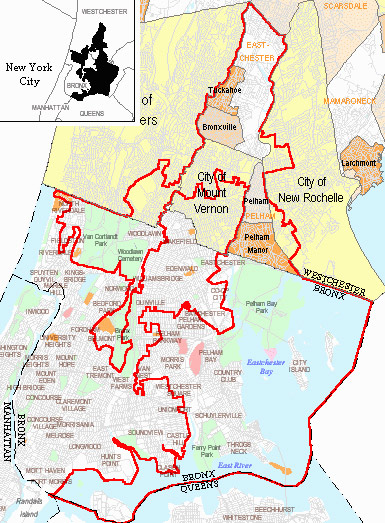

The board almost never elaborates on how it staffs positions. At present, its web site has no job posting or any indication that it even needs an executive director. City Councilmember Gale Brewer, who chairs the Committee on Governmental Operations, said, "I hope the Board of Elections will do an extensive search to identify the best person."

At previous Board of Elections commissioners' meetings, the board revealed it has two possible candidates, former Queens Councilmember Anthony Como and the board's current deputy executive director, George Gonzalez. But there is no public information on how the commissioners are conducting their search.

Although "both candidates have a lot of experience with the board itself," Rosenstein said, he expressed disappointment that the board is not conducing an open and wide-ranging search for the most qualified person.

Gotham Gazette asked board spokesperson Valerie Vazquez-Rivera about the executive director's responsibilities, how tasks were being handled during the vacancy and the search for a replacement. After two weeks, Vazquez did not reply to our inquiries. Individual commissioners also did not reply to requests for comment.

An Opaque Board

According its critics, transparency has never been the board's forte. It does hold public meetings and communicate with public interest groups, but observers note that the board still does not truly reveal how it works.

"It's extraordinarily secretive, and that's a problem," said Paul Newell, a Democrat who was recently elected as district leader for Part C of the 64th Assembly District. Newell said that the lack of transparency preserves status quo, and the status quo maintains existing problems.

Twelve public interest groups, including NYPIRG and Citizens Union (whose sister organization publishes Gotham Gazette) have called for "an open and public search" for the executive director position. The groups have been pressing the board to select someone who has strong experience with election administration, voting rights, and information technology.

A Bipartisan Patronage System

The city's Board of Elections is a bipartisan organization. Its 10 commissioners are split evenly between Republicans and Democrats, one of each party from each borough. The commissioners, who are selected by their respective parties, vote to appoint the executive director and other staff positions, which also must be evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats.

New York State adopted this bipartisan structure in 1894 as a way of having the two strongest political parties -- the Republicans and Democrats -- serve as a check on each another. But numerous critics have charged that this system has allowed political patronage to take hold since it places no checks and balances on how the parties bring their own candidates to the board.

"Virtually every single employee of the board, as well as the executive director, are hired through the patronage process," said Rosenstein, who explained that local party bosses hold influence over board's commissioners, who in turn select the executive director and other staff. It is a selection process, he said, based on a loyalty rather than merit with no nonpartisan oversight.

The last executive director, Marcus Cederqvist, had a long relationship with the Republican Party. According to a 2002 biography on the New York Republican County Committee's website, Cederqvist was chief of staff for former City Councilmember Andrew Eristoff for six years and Republican district leader for the 64th Assembly District between 1995 and 2002. Cederqvist told City Hall News in March 2008 that Republican John Ravitz, the board's previous executive director, had approached him about the position.

Nothing in Cederqvist's background suggests that he had any particular management or voting expertise. In fact a November 2008 editorial in the Daily News accused Cederqvist of having "less management experience than a street-corner hot dog vendor."

The board, which unanimously approved Cedarqvist's selection, would not comment on why he was chosen.

When problems occurred at the polls during the 2008 presidential election, some blamed Cederqvist, but other watchdog groups considered that unfair, given his short tenure at the board and its long history of problems. Margaret Fung, executive director of Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund said Cederqvist was attentive to suggestions and was simply not in the post long enough to be adequately judged on his leadership.

What the Board Needs

Yet with the election process in New York facing such huge changes, critics and public interest groups say the city cannot afford to take a complacent or wait-and-see approach to Cederqvist's successor, whoever it is. "We need the most qualified executive director, we don’t need one who tows the party line or the party boss' line," said Rosenstein.

Fung said that any incoming executive director needs to understand the issues faced by the city’s many groups.

An understanding of new technology is especially important because the new voting system will use optical scanners to count ballots. In addition, the new machines will be able to display ballots in different languages, raising an increased possibility of translation mistakes.

In January, the board awarded the multimillion contract to Election Systems & Software, Inc. One day after the contract was awarded, a lobbyist for Election Systems was arrested on accusations of bribing a Yonkers City Council member. Shortly thereafter, a rival vendor sued the board, alleging that it awarded Election Systems points during the bidding process for technology features that cannot legally be used in New York.

Even though a court has not decided on the rival vendor’s allegations, Howard Stanislevic, founder of the E-Voter Education Project, believes that the controversy underscores the kinds of problems that can arise if the board hires an executive director who is not proficient in voting technology, and the laws governing it.

"Election administration has become more of a [technology] job," said Stanislevic. "You need people with experience otherwise the vendors will control everything."

Bill Aims for 'Pork Equality'

A flood of cash raced into some State Senate districts in the city last year as Democrats took control of the Senate for the first time in decades. Sen. Malcolm Smith brought home $5.7 million worth of member items in 2009, up from just $657,000 only one year before. Other members of the Democratic leadership, like Sen. Jeff Klein, also delivered several millions of dollars in pork to their districts, but most legislators brought home much less, with some senators falling far short of the million dollar mark.

A study by New York Public Interest Research Group and three other good government groups found that the average Assembly member received $300,000 in member item distributions and the average senator took home around $1.2 million in member items. Most districts in the city and the state, though, received much less than their fair share. Analysis by the Citizens Union reveals that residents who live in 49 of the 64 city based Assembly districts that received member items and in 11 of the 26 Senate districts received less than the average amount typically spent on member items.

Now a group of legislators is proposing legislation that would make sure every district gets the same amount of member item cash. It also would create new measures to make sure member items are awarded responsibly.

Where the Money Goes

For years the majority of Senate member item spending was concentrated in the districts of the Senate Republican leadership. Meanwhile, in the Democrat-controlled Assembly, most of the member items went to city districts of the Democratic leadership -- especially the Manhattan district of Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver.

Since the shift in control of the Senate, spending on member items has skewed even more sharply to the legislative leadership’s districts, while the districts of rank and file legislators get less than their fare share. Assembly district are supposed to have roughly the same amount of constituents as are all Senate districts.

So while Smith pulls in more than $5 million in pork, Sen. Bill Perkins and Sen. Shirley Huntley each brought home $1 million in member items -- about $300,000 less than the average allocation of member items -- even though they are in the majority party. Republican senators who represent New York City received even less. Republican Sens. Martin Golden and Andrew Lanza were each able to deliver just $250,000 to their districts, over $1million less than the average.

Statewide data shows that 69 percent of New Yorkers live in a Senate district that received less than the average allocation, and 81 percent of New Yorkers live in an Assembly district that similarly came up short.

Check out the 2009-2010 Assembly member item allocations here. The Senate allocations can be found here.

Policing the System

It isn't just the disparity in spending that concerns good government groups and reform minded legislators. Member items have been a repeated source of scandal over the years as legislators have used them to reward groups run by the family members or political allies.

Currently, party leadership is supposed to review where member items are going. Then the attorney general's office also conducts a review.

Under the proposed legislation, the attorney general's office would pre-certify groups before they received any cash, and state agencies would audit the groups to make sure the money was being spent for the approved purpose. "It is important to make sure that an elected official is checking to make sure these are legitimate groups that are receiving money, just like the mayor does in New York," said Dick Dadey, executive director of Citizens Union of the City of New York. (Gotham Gazette is published by Citizens Union Foundation, the sister organization of the Citizens Union. )

The names of the groups receiving the grants and the legislators awarding them would have to be made public 24 hours in advance of the budget to allow for public comment. Legislators and recipients would also have to provide documents proving they do not have any conflicts of interest.

The New York City Council uses a similar method to screen organizations. Although it has not been foolproof, advocates say it is a step in the right direction. "If New York City can do it, the state can do it," said Dadey, "and the state is in worse financial shape."

The Power of Pork

Blair Horner of the New York Public Interest Research Group said he hopes that New Yorkers will see the disparity in the distribution of member items and push their legislators to support the legislation. Right now, besides the bill's sponsors, the proposed legislation has decent backing among rank-and-file members in the Assembly and sparse support in the Senate.

"It will take a while to change the culture," said Jose Serrano, the bill's sponsor in the Senate. "There is a group who think that member items are the life blood of politics," he said, referring to the leadership's ability to reward loyalty and bolster flagging candidates by sending them more member items. Sens. Liz Krueger, ,Eric Schneiderman and <ahref="http://www.gothamgazette.com/campaigns/whosrunning.php?t=indiv&id=258">Daniel Squadron are co-sponsors of the legislation.

Serrano said he think the idea that member items translate into backing and votes "is a myth." He said the Democrats' ability to win a majority in the Senate in 2008 shows that member items are not the be-all and end-all. "They [Republicans] had millions to hand out for decades, but we took control. People voted for policy," Serrano said.

Some Democratic members balk at making changes that would limit their new-found wealth and power. "At the very time that we have finally got black and Latino leaders, all of a sudden we're looking to limit. We've never had that before. We had old white guys running the chamber for 250 years," Sen. Kevin Parker said, speaking about rules changes approved last year that mandate among other things that the majority party will get two thirds of all pork an the minority party one third.

"When I was in the minority I railed against how unfair it was for the majority to be getting 85 percent of the member items," said Serrano. "It would be the height of hypocrisy if now that I was in the majority I didn't speak out." But Serrano is doing more than speaking out and pressing for his legislation. He and the bill's sponsor in the Assembly, Sandy Galef have decided not to partake of member items during this year's budget process.

Barbara Bartoletti of the League of Women Voters said that member items do have a purpose. She noted that funding for health clinics in schools began as a member item. An increasing number of legislators allocated member item funding for the clinics over the years until eventually the funding became a standard part of the budget process, and the money was no longer distributed through member items. As the economy has grown worse, a lot of member item spending keeps essential services such as homeless shelters, food pantries, health clinics and teen outreach groups afloat. Bartoletti notes that some legislators really use their funds exclusively for that purpose.

Regardless, Blair Horner of NYPIRG said that the system is in critical need of repair. "If they can't reform the system they should just eliminate it," he said.

Bloomberg Moves to Change the City Charter, But How?

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, making good on a promise in his 2008 State of City speech, announced on March 3, the creation of a charter revision commission. The mayor called for a comprehensive look at the structure and operation of city government, charging the commission with “examining the changes made by the 1988 and 1989 Charter Revision Commissions, and other subsequent changes, in light of the lessons learned over the past two decades and the new challenges and opportunities that have since arisen.” The mayor also charged the commission with conducting an extensive outreach campaign: “Every issue will be on the table, and every voice will be heard."

The mayor appointed Matthew Goldstein, chancellor of the City University of New York, to chair the commission, and John Banks, former chief of staff to New York City Council Speaker Peter Vallone, to serve as vice chair. The other 13 members included business, community and religious leaders, sitting and former government officials, educators, mayoral staffers and political operatives. Bloomberg also announced that the Citizens Union would conduct its own review of the charter, which the mayor said would be a great resource for the commission. (Citizens Union's sister organization is the publisher of Gotham Gazette.)

The commission would be the fourth under Bloomberg and the seventh since the last comprehensive charter review — the commissions appointed by Mayor Ed Koch in 1988 and 1989. Bloomberg had announcedin his Jan. 17, 2008 State of the City that he would appoint a commission, which, he said, would "conduct a top-to-bottom review of city government over the next 18 months."

But the commission never happened. The reason: Bloomberg wanted to run for a third term in 2009. Had a commission placed on the ballot an extension of term limits, the voters would have likely voted it down, as they had in 1996. Polls in 2008 showed widespread support for term limits and no enthusiasm for loosening them. Instead, term limits would have to be changed legislatively by the City Council.

Lauder Turnaround

In his effort to extend term limits, Bloomberg needed to at least neutralize Ron Lauder. Lauder funded the initial 1993 charter change establishing term limits and the defeat of a proposal to extend the cap to three terms in 1996. So in fall 2008, the mayor made an http://www.villagevoice.com/content/printVersion/1393325 offer that Lauder chose not to refuse — Lauder would support a "one time exception" to the two-term limit in exchange for a seat on a charter commission formed after the 2009 elections.

But Lauder was not named to the 2010 commission. It appears that Lauder, after conversations with the mayor, had decided that he would become a lightning rod for attacks on term limits, and that he could do more to restore the earlier limits outside the commission. He could once again use his personal fortune to contest any action by the commission that he might find objectionable. Lauder’s absence would also preclude charges that Bloomberg’s agreement with Lauder was a bribe. Indeed, NYPIRG and Common Cause had filed a complaint on Oct. 8, 2009 with the city's Conflicts of Interest Board charging Bloomberg with violating the city's ethics laws when he pledged to put Lauder on a charter commission in exchange for his support for the term limits extension. Two members of City Council -- Bill de Blasio, now the city's public advocate, and Letitia James filed a separate complaint with the board. (The board, appointed by the mayor with the advice and consent of the City Council, did not find a conflict.)

Changing the Charter

The charter is the governing document of the city; it establishes the framework within which the city governs itself. It defines the organization, power, functions and essential procedures and policies of the city's political system; it establishes the authority and responsibilities of the city's elected officials. It also lays down the basic structure of the city's finances. It is a large document (currently 356 pages), packed with organizational minutiae, much of which belongs in the Administrative Code.

Charter adoption and revision in cities in New York State is governed by Article 4, Part 2 of the Municipal Home Rule law. The law provides for the appointment of a charter commission in New York City through City Council action, a petition followed by a referendum approving the creation of a commission or mayoral action. Mayoral action takes precedence over the other two, letting mayors use commissions as political tools.

Not all charter revisions have to come from a charter commission. They can be placed on the ballot through passage by the City Council or through petition by at least 50,000 registered to vote. The amendment establishing term limits was enacted by popular vote in 1993 after a petition drive; The City Council placed the unsuccessful 1996 proposal to extend the number of four-year terms from two to three before the voters.

The charter is a "fluid" document, which is often amended, sometimes by city voters, most frequently by local law -- as the council did in its October 2008 vote to revise the charter's term limits provision. A popular vote is required if the amendment relates to the manner of voting for elective office (not the term or tenure of those offices), creates a new elective office or redistributes power.

New York's first City Charter was drafted by a city commission in 1936 and implemented in 1938. Prior to the 1924 Home Rule amendment to the State Constitution, city charters were amended by special acts of the legislature. Commissions in 1963, 1975, 1988 and 1989 proposed significant revisions to the charter, which voters then adopted.

Charter commissions are charged with reviewing the entire city charter, though mayors through their "charges" broadly set the commission's agenda. The commission must produce reports, including proposals to adopt a new charter or revise the existing one. All proposals must be adopted by the city's voters not later than the second general election after the commission's appointment. The recommendations of the commission can be voted as one omnibus measure (as in 1989 and 2001) or as separate proposals (the other post 1989 commissions).

The Koch and Giuliani Commissions

The recent history of charter commissions shows two very different approaches, one by Koch, the other by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. Koch, responding to the Supreme Court's decision declaring the Board of Estimate unconstitutional, created a commission in1988 to come up with a new structure for city government. The commission, with highly regarded, independent chairs Richard Ravitch (now lieutenant governor) and Frederick Schwarz and commissioners of high quality, had an experienced, knowledgeable professional staff, which produced comprehensive studies of electoral systems and institutional structures and processes. It consulted widely with government officials, civic leaders, advocates and community members, holding dozens of public hearings throughout the five boroughs.

The process took three years, employed 52 full-time staffers and entailed 141 public hearings over two years. The commission, proving itself a medium of positive, meaningful change, created the system New York has today, with a 51-member City Council, a public advocate elected city wide and limited roles for the borough presidents.

Giuliani, on the other hand named three charter commissions, each chaired by close associates, with long-time friends or political associates as commissioners. His consultations and public hearings were largely perfunctory.

The commissions were, Giuliani frankly admitted, political tools. The Municipal Home Rule Law Section 36 (5)(e) provides that the placement on the ballot of a valid proposal initiated by a charter revision commission will "bump" other referenda off the ballot. The courts have affirmed this provision even when there is recognition that a charter revision commission has been created expressly to keep other proposals off the ballot. There is currently a bill in the State Assembly (A6019) which "eliminates the rule that provides that whenever a city charter commission puts a proposal on the local ballot,all other local referendum proposals are barred from the ballot."

In 1998, the mayor used charter revision as a political maneuver to block from the ballot a referendum proposed by the City Council on whether the city should build a West Side stadium to replace Yankee Stadium. A year later, he created a commission to change the city's succession procedure, largely to stop Public Advocate Mark Green from becoming mayor if Giuliani left his job for the U.S. Senate. A 2001 commission dealt with minor administrative changes that could have been dealt with by local law rather than constitutional change. In each case, the mayor got what he wanted from the commission, though the voters largely rejected the recommendations. (For more on Giuliani's specific proposal, see Charter Commissions Since 1989.)

Bloomberg's Commissions

Bloomberg created three prior commissions -- in 2002, 2003 and 2005 -- his approach has been a hybrid of Koch and Giuliani policy concerns, political motivation, and commission personnel. He has been Koch-like in selection of commissioners and chairs (though "the fix was in" on non-partisan elections, and the chair of the 2005 commission, Ester Fuchs, had been serving as a senior advisor to Bloomberg). But the mayor was Giuliani-like in his creation of the 2005 charter commission as a tool to forestall placing a class size proposal on the ballot via referendum.

The commission that Bloomberg appointed in 2002 represented Koch's approach in the selection of commissioners and the chair, Robert McGuire. Also, the issues addressed, the nature of the city's voting system -- the mayor had charged the commission with examining nonpartisan balloting -- and succession to the mayor, were significant. However, the press and civic groups such as Citizens Union and the Women's City Club roundly criticized Bloomberg for the short timetable for crafting the recommendations-- far shorter than any charter commission in the prior 70 years.

The McGuire Commission proposed one ballot measure that changed mayoral succession from the public advocate being mayor until the end of the former mayor's term to serving as interim mayor only until a special election to be held within 60 days of a vacancy (what Giuliani had wanted but without the enmity toward the public advocate that Giuliani had for Mark Green). City voters adopted the change. The commission, like those in 1998, 1999 and 2001, chose not to place nonpartisan balloting before the voters.

The mayor was determined to establish nonpartisan elections for city offices and in March 2003, announced the creation of the fifth charter commission in six years, charging it with considering nonpartisan elections for all city officials and putting such a proposal on the November ballot. He named Frank Macchiarola, the president of St. Francis College, chair. Macchiarola announced that a proposal recommending nonpartisan elections would be placed on the ballot in November before any other commissioners were named.

Non-partisan elections and the commission's handling of the issue generated much opposition -- from often-strange political bedfellows. The commission never adequately addressed the substantive critiques of non-partisan elections and never explored the possible consequences of the system it ultimately proposed to the voters. Indeed, the system that the commission proposed in September was the system in place in Jacksonville, Fla., which had limited experience with it and, unlike New York, did not have public campaign financing or term limits. There was just not enough evidence to make major changes in the voting system, irrespective of calculations of political wins and losses. Voters overwhelmingly rejected the proposal, despite the fact that the mayor bankrolled the pro-change effort with $7 million of his own money. (Surely, this was the first time that a sitting chief executive funded a constitutional change that would benefit him.)

In 2005, Bloomberg, like Giuliani, used the charter revision process as a political weapon. Proponents of smaller class sizes gathered far more petition signatures than required to place the matter on the ballot. The mayor and his Department of Education opposed setting rigid limits and so sought to preclude the referendum from appearing on the ballot by promoting charter revisions of their own. Fuchs, a Columbia University professor and senior policy advisor to the mayor, chaired the commission. It followed the Koch model: well-respected independent commissioners, wide public outreach and professional staff research. The commission placed "two rather obscure measures" on the ballot. One established ethics rules for administrative hearing officers; the other would add financial management requirements into the charter. Voters approved both.

What Will/Should the Commission Do?

Overall, in the 20 years since the 1989 restructuring, the number of charter changes approved by the public has been few and the substance narrow. In 2010, the charter remains essentially the framework established in 1989. So what can we expect to happen with the new charter commission? What should happen? Will it actually conduct the sweeping, comprehensive review and put forth the substantive recommendations that the mayor promised and the 1988-89 commissions delivered? Or will it focus on just a few matters?

Charter revision raises two sets of questions: those on process and structure, and those on possible, needed or likely substantive proposals. Among the process and structure questions: What should be guiding goals and principles of the commission? What makes a "good" commission and commissioners? What is desirable staffing, budget, timeframe? What has been, is and ought to be the role of the mayor?

Any rigorous review of today's charter must begin with the 1989 commission: What has worked? What hasn't? Why? How do we "fix" it? Any unwanted consequences lurking? A comprehensive review in 2010 would likely be framed by three broad themes, as it was in 1989: centralized power vs. local advice and consent; governmental checks and balances (essentially, how to contain the power of the mayor) and expansion of an informed electorate.

What is certain to be addressed by the 2010 commission is term limits. The 2010 charter revision commission owes its existence to term limits -- or rather to their extension. Without the council overturning two prior citywide votes, Mike Bloomberg would be writing checks from his foundation, and there would be no Goldstein Commission. The commission could recommend elimination of term limits entirely, a return to the two-term limit for all city elected officials, making Mike Bloomberg the "one time exception," or conclude that the current three-term limit or a variant is best. Should changes to term limits be subject to mandatory approval by voters?

Chancellor Goldstein, on being named chair, stated, "Certainly term limits will be something we will consider but beyond that I don’t want to speculate."

But speculation is in order.

Given that land remains one of the principal stakes in the New York political game, zoning and land use policies -- less glamorous but with far greater effect on the city and the well being of its neighborhoods and residents -- will very likely be a subject of commission discussion. The Bloomberg administration and real estate developers see the current city land use policies, notably the Uniform Land Use Review Process or ULURP, as inefficient, time consuming and often wrong-headed. They would like to see it "streamlined" with such changes as shorter time frames for review and elimination of some steps. Others want enhanced purview and greater powers for community boards and City Council on zoning and land use matters. The commission could also look at the composition and authority and processes of the City Planning Commission and the Board of Standards and Appeals.

Among the other topics that a comprehensive commission may address (with different degrees of likelihood) are:

- the powers and purviews of the mayor, City Council (such as increasing the size of the council; making it a full-time body with limits on earned outside income; enhancing its budgetary role), comptroller (whether the comptroller should have power to establish or sign off on revenue estimates), public advocate (retain or eliminate the office; whether to give it a dedicated funding stream or subpoena power), borough presidents (retain or eliminate; maintain, reduce or enhance authority in areas such as in land use decision making and capital planning and budgeting), and the advisory community boards (providing an enhanced role in planning/land use; providing them with professional support);

- voter participation, such as non-partisan voting, runoffs and immigrant /non-citizen voting;

- ethics, including appointments to and the purview and procedures of the Conflict of Interest Board, and oversight of lobbying activities;

- campaign finance (changes necessitated by the Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. the Federal Elections Commission; elimination of public funding in non-competitive races; the disclosure of private spending by self-funded candidates);

- procurement (enhanced bidding and contracting oversight by comptroller or City Council)

- charter content (such as moving much of charter to Administrative Code)

The public advocate's position and the role of the borough presidents have long been subjects of conversation. In October, at a Staten Island Advance editorial board interview, Bloomberg said that eliminating the public advocate’s office could be on the table. He also said that while he might be open to giving borough presidents a different role, he was not prepared to give them more power by taking it away from City Council.

It is unlikely that a charter commission would move to further weaken or eliminate the public advocate or the borough presidents. After all, the closeness of Bloomberg's November win resulted from public disenchantment with Bloomberg's term limits end-run. Undercutting potential sources of opposition would only reinforce the view of him as an "imperial mayor."

Non-partisan elections may once again be on the table. It's been reported that in spring 2009 when he was seeking the Independence Party endorsement, Bloomberg told party leaders he was open to again looking at non-partisan elections. Dissatisfaction with the current runoff system for citywide officials (if no candidate gets 40 percent, the top two finishers compete in a runoff two weeks after the primary), might lead to study of alternatives such as Instant Runoff Voting.

Time and Money

For the Goldstein commission to act in any meaningful way to meet the mayor’s charge of a comprehensive charter review where "every issue will be on the table" will be close to impossible in the less six months that the commission has to make recommendations to be placed on the ballot for this November. (Proposals must be submitted 60 days before the November election). It is certain that the short time frame will generate much concern and criticism.

Chancellor Goldstein stated that he envisioned that the commission’s work would probably last until 2011 but that a few recommendations would be made early enough that they could be placed on the ballot this year. However, under state law, charter commissions expire once the balloting on their recommendations takes place. So the Goldstein Commission would go out of business on Wednesday, Nov. 3, 2010. The mayor could then create a commission with the same or similar membership that could place recommendations on the Nov. 2011 ballot. This happened in 1988 and 1989. The 1988 Ravitch Commission expired after the 1988 general election. In 1989, Mayor Koch appointed a commission with Frederick Schwarz as chair (Ravitch was running for mayor in the Democratic primary). That commission went out of business after the 1989 November elections.

And then as always with this mayor, there is the question of funding: Is Bloomberg going to put money into it as he did $7 million in 2003 in the nonpartisan election vote? Will he get better returns?

Warning: Expect the Unintended

Whatever specifics it considers, the 2010 commission in its deliberations and recommendations should beware the law of unforeseen and unintended consequences: Actions of people -- and notably of government -- will always produce some unintended, unanticipated and usually unwanted consequences, and these effects can be more significant than the intended effect.

Jimmy Flannery, the Chicago sewer inspector, machine ward heeler, sleuth and protagonist of Robert Campbell's crime series, has a warning in The 600 Pound Gorilla for those who would tinker with a city's government: "A thing like a city government is like a tower built out of match sticks. It stands so rickety you think one breath'll knock it flat. Somebody decides to fix it. Take out this rotten beam and that rotten brick. Chop out a floor, pump out the basement, add a garden room. Then everybody acts surprised when it comes crashing down."

Douglas Muzzio is a professor of public affairs at Baruch College and co-director of the Center for Innovation and Leadership in Government. He co-authored (with Professor Gerald Benjamin) the 1988/1989 charter revision commission's study on the City Council and alternative voting systems. He was an expert witness before the 2003 charter commission on nonpartisan elections and will serve on the recently created Citizen Union's panel to review the current charter.

For a comprehensive review of the 1988 and 1989 charter commissions, see Frederick Schwarz and Eric Lane, "The Policy and Politics of Charter Making: The Story of New York City's 1989 Charter, "New York Law School Law Review," Vol. XLII, 1998; for an examination of those commissions and the six subsequent ones, see Ida Cheng, Jenifer Clapp, Arianne Garza, Liz Oakley, and Gregory Wong, "NYC Government: 1989 and Today," Citizens Union, April 27, 2007.

Charter Commissions Since 1989

|

Mayor |

Date |

Chair |

Ballot Proposal(s) |

Voting Result |

|

Rudolph Giuliani |

2/19/98 |

Paul Crotty |

Revamp city campaign finance law and bar corporate donations |

adopted 60-40% |

|

Giuliani |

6/15/99 |

Randy Mastro |

1. Impose a cap tied to the inflation rate on city budget increases. |

rejected 76-24% |

|

Giuliani |

7/15/01 |

Randy Mastro |

1. Make the Mayor's Office of Emergency Management a permanent charter agency. |

all approved: Ballot Proposition #1 approved 70 to 30%; Ballot Proposition #2, passed 73 to 27%; Ballot Proposition #3 passed 55 to 45%; Ballot Proposition #4, passed 64.5 to 35.5%; Ballot Proposition #5, passed 67-33% |

|

Michael Bloomberg |

7/11/02 |

Robert McGuire |

Change mayoral succession. The public advocate would be interim mayor and a special election held within 60 days |

adopted 61-39% |

|

Bloomberg |

3/26/03 |

Frank Macchiarola |

1. Create a new system of "non-partisan" elections for all city officials. |

rejected 70-30% rejected 64-36% rejected 65-35% |

|

Bloomberg |

8/19/04 |

Esther Fuchs |

1. Establish ethics rules for administrative law judges and hearing officers |

adopted 79-21% adopted 71-29% |

* Commissions expire the day after their ballot proposal are accepted or rejected by the voters in the general election.

For an examination of the 2010 charter commission and its predescessors, see Bloomberg Moves to Change the Charter -- But How.

A Barrage of Bills

Photo (cc) Ya-Hsuan Huang

If we can learn one thing from the last session of the City Council, it's that introducing bills won't ensure you're re-elected.

Former Councilmember Alan Gerson, who lost his third term re-election bid to Margaret Chin last fall, was the first primary sponsor of more bills than any other council member in the last session. He introduced 84 pieces of legislation -- more than triple the average council member, according to council records. Only seven of his bills became law.

Gerson, whose legislative records are still packed in boxes and who is planning his first vacation in eight years, said his legislative history was "overstated" -- 10 of those proposals would have regulated street vendors, which he likened to a package rather than individual bills. Nonetheless, he does take some pride in his s-called achievement.

"We are a legislative body and the way to make a difference on a legislative body is problem solving through legislation," said Gerson.

But not every member took that approach. Council members Darlene Mealy of Brooklyn and Larry Seabrook of the Bronx were the first primary sponsors on just three bills in the last four years -- less than any other council member who served a full term between 2006 and 2009. Neither returned calls for comment.

There may be a lot that goes into being a member of the City Council, but one of its primary responsibilities is to propose, hear and enact legislation. According to an analysis by Gotham Gazette, some council members take that job far more seriously than others.

The Last Term

Under Council Speaker Christine Quinn's first term, 25 percent of all bills introduced became law -– a slight decrease from the number of bills approved under her predecessor, Gifford Miller. During his tenure, 31 percent of all bills were approved.

| Councilmember | Number of Bills Sponsored | Number of Bills Passed |

| Alan J. Gerson | 84 | 7 |

| David Weprin | 70 | 43 |

| Tony Avella | 64 | 2 |

| Gale Brewer | 63 | 6 |

| Peter Vallone Jr. | 55 | 10 |

To see the full breakdown, go here.

As defined by the City Council, a first primary sponsor is the member whose name is listed first on a bill when it is initially introduced. That legislator usually lobbies other members to sign on to the bill and often spearheads it through the legislative process. Council members do co-sponsor legislation with other officials and can introduce legislation together as a team. For those bills, our analysis counted only the first primary sponsor.

In the last session, which spans from January 2006 to January 2010, 1110 bills were introduced, according to the council. They range from the sensible to the outlandish -- from regulating the licensing of pedicabs to prohibiting peeping toms.

At times, members can be given credit for legislation that is pro forma, which has been assigned by the speaker's office to the committee they chair. For instance, former Councilmember David Weprin, who headed up the Finance Committee, was the primary sponsor of 70 bills in the last term. Many of them were standard finance-related actions, like the approval of business improvement districts, and some were submitted to the council at request of the mayor.

We have also not taken into account whether members accomplished their legislative goals through other means, such as through regulation or executive order. For instance, Gerson introduced legislation to change the way the Department of Transportation installed metal plates on streets -- an attempt to silence some of the cacophony created when a truck or car passes over them. His legislation was not approved, but Gerson said the changes were implemented through departmental policy.

And, officials said, the number of bills someone sponsors says nothing about the merit of those proposals.

"I do not believe the effectiveness of a legislator is measured by the quantity of the bills they have introduced, but rather by the quality of those bills and their impact on those they are meant to protect," said Councilmember Al Vann, who fell within the bottom of our analysis. He introduced six bills, including a proposal to designate high poverty areas as community development zones, a bill to require city-subsidized developers to prepare community impact reports and a proposal to give senior citizens protection from water bill liens. "I would be willing to put those bills up against any other three by another member as far as their importance to New Yorkers," he said.

Nonetheless, other officials argue there is a difference between some members authoring legislation in scores and others in single digits.

"Let me be kind and say perhaps they are focusing their efforts elsewhere," said Councilmember Peter Vallone Jr., who introduced 55 bills in the last session.

Swinging Away

Quinn by far has the best batting average for passing legislation. Of the 36 bills she sponsored, 78 percent became law -- the highest percentage of any council member. As speaker, Quinn sets the council's legislative agenda, and whatever she wants to move -- whether to a hearing or to the chamber floor -- will move.

On the other hand, some members, like Councilmember Charles Barron, claim the speaker's agenda setting can amount to political arm-twisting. If you don't make nice, your bill is like lead -- it sinks.

"When you're not in favor of the speaker your legislation will not be voted out of committee," said Barron.

Barron was the only member to not have any bill approved last session. He introduced 11 of them. On average council members got a quarter of their sponsored legislation approved.

Maria Alvarado, the speaker's spokesperson, said: "Every bill that is introduced goes through the same legislative process where it is fully reviewed and debated. Legislation moves forward by building a consensus and is passed based on its quality and merits. A bill's sponsoring member is not a factor."

At the beginning of her tenure as speaker, Quinn enacted several reforms aimed at giving individual council members more of a say over what happens to legislation. The move was seen as a break from the past, and was lauded by good government groups.

The reforms included a rule to allow members to bring legislation stalled in committee to the floor if the bill had more than seven sponsors. Quinn also installed a rule to allow members to propose amendments to legislation on the floor of the council.

Each of those rules has been triggered once in the last four years. An amendment was offered on the floor when the council considered term limits. It was defeated.

Councilmember Robert Jackson last December filed a "motion to discharge" to bring his proposal to require arbitration during commercial rent disputes to the floor. He later retracted the motion after fellow sponsors backed away from the bill.

Despite that defeat, Jackson said the legislative process is better under Quinn. "It's been much, much easier to move stuff if there is a disagreement… under Christine Quinn in comparison to four years earlier," he said.

Several measures that had the support of a majority of council members, such as a bill requiring paid sick leave, never came to the floor.

Last month, Citizens Union, the sister organization to Gotham Gazette's publisher, issued a report looking back at Quinn's proposals. While Citizens Union commended many of the council's reforms, it did suggest the council give individual members more freedom and independence to act on legislation. It should encourage members to offer amendments, the report states, without fear of political payback.

Albany's Ethics Bill: First Step or Missed Opportunity?

Photo (cc) Courtney Gross

Three of the four leaders of the legislature and the heads of three major good government groups stood together in Albany on Wednesday morning and patted each other on the back for a job partly done.

"It's not the best thing since sliced bread," said Barbara Bartoletti, legislative director of the League of Women Voters, speaking of the ethics package that was 16 months in the making. "This is, for all of us and all of you, a very good loaf of bran," Bartoletti concluded. Senate Democratic Conference Leader John Sampson described the package as a "down payment on other things to come."

The ethics deal, which came together after months of negotiation between Senate and Assembly Democrats, is not the "whole enchilada," as one legislator put it -- or as sweeping as a proposal put forth by Gov. David Paterson earlier this month.

However Blair Horner of New York Public Interest Research Group, Bartoletti and Dick Dadey, executive director of Citizens Union, decided to support the legislature's package. (Citizens Union's sister organization, Citizens Union Foundation, publishes Gotham Gazette.) This package would create three new ethics oversight committees, require more financial disclosure from politicians and lobbyists and strengthen the Board of Election's enforcement wing. It is, the three groups say, a good, solid step, and they hail the fact that the legislation will sunset in four years, meaning legislators will be forced to evaluate and perhaps improve the rules.

The fourth major good government group, Common Cause/ NY opposes the legislature's package.

"I think it's very disappointing," said Susan Lerner of Common Cause/ NY, "I don't think it should be enacted. We are not looking at it in terms of who proposed what. We are asking, 'Is this enough change to current law to address the crisis of corruption?'"

Lerner isn't the only one who is disappointed.

A number of Senate Democrats have complained privately that the package doesn't go far enough at a time when the public's awareness of corruption in Albany has reached a peak. From the conviction of former Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno on federal corruption charges to recent allegations against Sen. Pedro Espada, the public has been hammered with the reality of corruption in Albany.

The Governor's Moves

Yesterday's meeting in Albany came as the atmosphere surrounding ethics in the capital had become increasingly contentious -- so much so that some say Patterson might veto the bill on the grounds that it does not go far enough or as far as his proposals do.

In his State of the State speech, Paterson proposed a package that Horner called the "kitchen sink and the stopper." It was so far-reaching -- instituting term limits and introducing public campaign financing -- that many observers thought it stood no chance of passing. "It's desirable, but it's dead on arrival," Dadey said of Paterson's proposal before the State of the State Address. "The Assembly and Senate will not agree to independent ethics oversight by an entity that they don't control."

As a result, Horner, Dadey and Bartoletti decided to back the legislators' plan. They admit it's not everything they want but believe it is what they can get right now.

Lerner disagrees. "There are those who are willing to settle for something less," she said, "and we can't give them the comfort that this will be enough in the eyes of the public."

Paterson chose to introduce his legislation without consulting the legislature or good government groups even though he knew the legislature was negotiating an ethics package. In addition, he lashed out at good government groups, calling them "drunk with power" and said he would require them to reveal their funding sources. Good government groups currently must disclose donations of over $5,000.

"We are not angry about the governor's package but angry at how he attacked us," said Horner. "We said nice things about his proposals. We are just skeptical of the governor's commitment. We are skeptical of his tactics and his assertions."

For his part, Paterson issued a statement Wednesday saying he was "stunned that legislative leaders would be so disrespectful to the public that only one week after he proposed a sweeping and real overhaul of the ethics system in Albany, they would try to pass this off as anything more than election year window dressing. This proposal does nothing to address the underlying issues that have caused the people of New York to lose faith and trust in their government."

He said he would "work with members of the legislature who are ready to pass meaningful ethics reform that changes the culture of Albany -- ending pay-to-play; full disclosure; breaking the special interests lock on Albany with strict campaign finance limits; and independent oversight."

Three Watchdogs

The ethics package would discard the Commission on Public Integrity -- the ethics watchdog group that currently oversees all branches of state government. That group has 13 members -- seven appointed by the governor and one each by the attorney general, comptroller and the four legislative leaders. Scandals have rocked the board and many have already called for its abolishment following a report by the inspector general that found the head of the commission had illegally leaked information to Gov. Eliot Spitzer. Since then individual members have drawn fire for serving as legal advisors during the last year's Senate coup and hosting fundraisers for legislators. One member even held a fundraiser to help pay Bruno's legal fees.

Three new oversight bodies -- one for the executive branch, one for the legislature and one for lobbyists -- will replace the Commission on Public Integrity. This basically restores the system that existed before Spitzer led the charge in 2007 to combine the State Temporary Commission on Lobbying and the State Ethics Commission into one body. All would have directors appointed to fixed terms who could be removed only for cause.

The governor, attorney general and comptroller would each name two members to the six-person Executive Ethics and Compliance Commission. This means the governor would not name a majority.

A Joint Legislative Commission on Ethics and Standards, with eight members -- four of them legislators -- will keep an eye on the legislature. Members would be named by each legislative leader. In other words, legislators will be able to appoint their watchdog. Paterson has said this is a major problem for him and that he would not rule out vetoing any package that did not include an independent oversight board for the legislature.

The commission also would have a department of investigation that would have subpoena power.

The six-member Commission on Lobbying Ethics and Compliance will have two people appointed by the governor and one by each of the four legislative leaders.

David Grandeau, who served as the executive director of former state lobbying commission, said he supported the legislature's proposal simply because it brings back a lobbying oversight board. Under his watch, Grandeau said, the body gained national recognition. When asked if he would like to be part of the new panel, Grandeau said, "We have to focus on getting this passed."

Paterson's bill would replace the Commission on Public Integrity with one five-member Government Ethics Commission. It would oversee all of state government rather than splitting oversight into three sections. The five members would be designated by a 10-member commission. Good government groups favor this model, but are convinced the legislature will not vote for an oversight board that they do not control.

Rules of Disclosure

Under the bills in the ethics package, legislators for the first time would be required to disclose how much income they make from outside employment. Lobbyists with any business before the state would be required to reveal any relationships they have with lawmakers, including any money paid to a consulting group or a law firm that employs any public official.

The legislation does not require lawyers, along with doctors and other so-called protected professions, to disclose their clients, which journalists and good government groups have been demanding for years. Sen. Ruben Diaz has said he would not vote for a bill that does not include that requirement. However, such a provision would certainly irk Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Sampson, since they both work as trial lawyers at prominent law firms.

The legislature's package would create an enforcement unit within the New York State Board of Elections and direct 35 percent of the board's annual budget to the unit. It would be harder for investigations to be stopped and easier for them to be started than is currently the case.

Penalties for campaign finance law violation would get tougher. For example, the fine for failing to file disclosure reports would double from $500 to $1,000, and legislators who failed to file more than three times in an election cycle could face a penalty of up to $10,000.

Paterson's proposal would place more restrictions on campaign donations, create a public campaign finance system and institute term limits. These proposals are not in the legislature's package. Silver has said repeatedly that "there is no sentiment" for term limits. He has served in the Assembly since 1976.

Will It Pass?

While the legislators' bill is almost certain to pass the Assembly with immense bipartisan support, its fate in the Senate is uncertain.

The Democrats' thin majority faces more peril by the day -- the Senate might have to delay its punishment of Sen. Hiram Monserrate to insure the bill gets a speedy passage.

Meanwhile, Attorney General Andrew Cuomo filed court papers presenting what Common Cause New York's Lerner called "damning evidence" against Senate Majority Leader Pedro Espada. The papers allege that the contract between Espada's healthcare network and its management company allowed him to siphon off funds for his political campaigns.

Then there is the question of whether the Democrats can count on support from every member. Diaz is already threatening to vote no, and Monserrate -- or his friends -- could use their votes as leverage to protect the Queens Democrat.

Democrats may in fact need help from Senate Republicans to pass the ethics reform bill, but the Senate Republican conference seems to be preparing to oppose the package. "It is unfortunate that despite their claims of bipartisanship, Democrats in the Senate and Assembly refused to include Senate Republicans in the negotiation of ethics reform legislation, and that they chose not to give us a bill draft until late yesterday," the Republicans said in a statement released Wednesday. "Apparently Speaker Silver and Senate Democrats think it's more important to negotiate directly with special interests than with the other elected officials they want to support the bill."

The statement continued that the Republican would review the legislation to see "how it differs from the ethics reform bill that Senate Republicans were prepared to support last year, before Senate Democrats pulled it from the floor to prevent a vote." They also said they might "offer amendments that seek to strengthen the bill."

Democrats insist Republicans had every chance to be involved in the process. When asked whether Senate Republicans were left out of the process, Austin Shafran, spokesman for the Senate Majority Conference, scoffed and rolled his eyes. "Taking ethics advice from Senate Republicans, with their history of corruption, is like taking marriage advice from Tiger Woods and Charlie Sheen," Shafran later toldthe Daily News.

Sen. Daniel Squadron, who was instrumental in negotiating the package, said that he hoped legislators could get over any perceived slights in the process or imperfections in the legislation. "It is more important to have a good bill than to have a perfect press release," he said.

Then, of course, the bill must win the governor's approval. Legislators say that it would be "suicide" for Paterson to veto the measure. However, in the atmosphere created by Paterson's caustic state of the state address anything could happen. Sampson and Silver were scheduled to meet with Paterson on the reform measure days before a deal was reached. Both leaders canceled on the governor at the last minute.

New Website Lets New Yorkers Talk Back to the Senate

Arrow image from wikicommons

After remaining on the sidelines for years, government now seems eager to keep up with the ever evolving world of technology and new media and even to advance it. Earlier this month, the New York State Senate continued with this trend, launching an Open Legislation website intended to make it easier for New Yorkers to find out about bills and comment on them.

Transparency initiatives should seem familiar to city residents. Since taking office as mayor in 2002, Michael Bloomberg has attempted use technology to achieve more transparency. While some of these efforts have been more successful than others, they have led to the creation of 311, a phone and internet hotline for government information, and to the city's offering an array of statistics on nyc.gov. The City Council has made the text of bills available through a keyword search on its website, as has the State Assembly. Unlike the State Senate's new program, though, these do not provide a place for people to leave comments.

Sen. Jose Serrano, who launched the site in front of students at Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics, believes that growing disclosure of the actions of the State Senate will increase citizen participation and make representatives more accountable, while also encouraging young people to get involved.

"Albany has been shrouded in mystery for so long to the point where the disconnect between the Albany legislature and the average person is beyond apathy," Serrano said. "I think this is a good initial step at creating a vested feeling for folks who are trying to access information."

Easier Access and Participation

The site, which debuted on Nov. 5, provides the full text of bills as well as the memo summarizing the legislation and offering the reasons for it. In this way it effectively allows those outside of Albany access to information that used to be available only to insiders.

The site does not seek to simply provide access but also tries to make it easy. Previously, doing a search required knowing the bill number.

Now, though, Open Legislation includes a Google-like search mechanism allows users to find bills by typing in a keyword. They can, for instance, search anything from "crime" to "school nutrition" and have all relevant bills appear on the results page. Performing a search on a broad keyword issue like "zoning elicits over 30 responses. For now (there are plans to possibly rework this), the results appear by bill number, rather than some other sort of distinction such as date. Visitors can view the bill in HTML, XML, CSV, or JSON format. The page for the legislation includes sections for a summary, action on it, the memo and its full text, topped off with the comments section at the bottom.

Visitors also can conduct searches by sponsor, committee, recent action or recent votes.

"We tried to build a very simple, easy to use search interface that we think will be useful to a lot of people," explains Andrew Hoppin, chief information officer for the Senate, who helped create the site with lead developer Nathan Freitas.

Those involved with the site seem most excited about the comments section. Serrano believes it will have a positive effect on future legislation.

"Traditionally, you had to go lobby physically in Albany, or you had to write memos of supporter opposition or be invited to go testify at a meeting," he said. Now, he continued, "We're trying to get the community engaged in a way that it hasn't been before. I want people to say, 'That's a great job Serrano,' or, 'No, you're totally off-base on this one, Serrano, and here's why.'"

He believes fellow senators will be receptive to their constituents' suggestions. "If elected officials have learned anything over the last year or so, it's that the public's voice needs to be heard and it needs to be heard in a meaningful way. When you partner with the public on legislation, you actually create a much better product," Serrano said.

Reaching Out to Youth

Serrano held the launch at the East Harlem high school not only because it is located in his district, but also because he hopes it will encourage young people, who tend to be technically savvy, to get involved in government.

After giving a brief explanation of the process of law making, Serrano invited the students to conduct their own searches. Some looked into education while others delved housing related bills.

"They live in apartments that may or may not be there for them in the coming future," the senator said, noting one student investigated vacancy decontrol. "Knowing that there's a bill that will protect affordable housing, they may want to get behind that."

Moving Forward

The website will remain in its beta form until it has been "battle tested by thousands of people using it for a number of months," said Hoppin.

And, while this may be the largest project aimed at transparency from the state in a while Hoppin said it will not be the last. A major overhaul of committee websites within nysenate.gov is also in the works. The goal is to better disclose information about committee meetings and hearing, while also providing live streaming video.

Serrano is working on launching a channel for the State Senate similar to CSPAN, where meetings would be broadcast live. He previously broadcast a committee meeting on YouTube and received what he felt were meaningful responses.

2009 General Election Results

Winners appear in bold. These results are based on the unofficial vote tally as reported by the wire services and, as much as possible, directly from the New York City Board of Elections.

The official count from the Board of Elections can take weeks to complete and will be posted as soon as they are available. The results below are subject to change as the official count is made public.

Citywide

| Office | Candidates | Date Posted |

| MAYOR | Michael R. Bloomberg (R, I), 50.62 percent Stephen Christopher (C), 1.65 percent Joseph Dobrian (L), 0.18 percent Dan Fein (Socialist Worker), 0.14 percent Jimmy McMillan (Rent is Too High), 0.24 percent Billy Talen (Green), 0.82 percent William C Thompson (D, WF), 46.04 percent Francisca Villar (Socialism & L), 0.32 percent |

- |

| PUBLIC ADVOCATE | Bill de Blasio (D), 76.90 percent Maura Deluca (Socialist Worker), 0.95 percent William J Lee (C), 3.56 percent Jim Lesczynski (L), 0.69 percent Alex T Zablocki (R), 17.90 percent |

- |

| CITY COMPTROLLER | Stuart Avrick (C), 2.44 percent John Clifton (L), 1 percent Salim Ejaz (Rent Is Too High), 1.26 percent John C Liu (D, WF), 76.02 percent Joseph A Mendola (R), 19.27 percent |

- |

Borough Presidents

| Office | Candidates | Date Posted |

| BROOKLYN | Marc L D'Ottavio (R, C), 13.24 percent Marty Markowitz (D, WF), 84.87 percent Michael Sanchez (L), 1.89 percent |

- |

| BRONX | Ruben Diaz Jr. (D, C), 86.87 percent Allison M Oldak (R), 13.13 percent |

- |

| MANHATTAN | David B Casavis (R), 15.92 percent Tom Baumann (Socialist Worker), 1.74 percent Scott M Stringer (D, WF), 82.34 percent |

- |

| QUEENS | Robert A Hornak (R), 20.31 percent Helen M Marshall (D, WF), 75.61 percent Robert Schwartz (C), 4.08 percent |

- |

| STATEN ISLAND | John V Luisi (D, WF), 37.26 percent James P Molinaro (R, I, C), 62.74 percent |

- |

City Council Races

| District | Candidates | Date Posted |

| Dist 1 | Margaret S Chin(D), 86 percent Irene Horvath (R), 14 percent |

- |

| Dist 2 | Bryan A Cooper (R), 16.09 percent Rosie Mendez (D, WF), 83.91 percent |

- |