We Should Never Have to Choose Between Life and Democracy

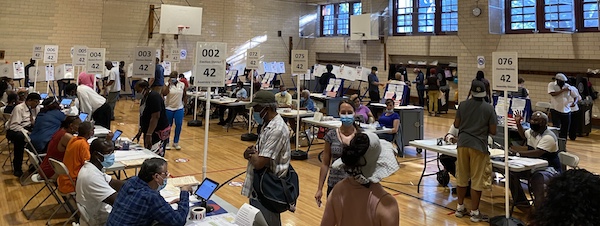

In-person voting during a pandemic (photo: Gotham Gazette)

We should never have to decide between public health and democracy. We must have both.

We hoped that voter suppression was a thing of the past, and yet it is still present not just in the South but in the South Bronx and across the country.

We are witnessing a public health and democratic crisis that must be addressed immediately—otherwise, lives will be taken as electoral gains are also stolen.

In short, the coronavirus crisis has cast a light on the deteriorating health of American democracy, and it’s time we act urgently.

In the midst of a global pandemic, state and local governments have had to adjust the way voters participate in elections to minimize transmission of COVID-19 and keep people safe, including using early voting and mail-in ballots so that people have options to cast their vote.

However, the past few months have shown that our electoral system is still in dire need of repair. The fact that it is taking weeks to count ballots in the South Bronx, for example, does not bode well for upcoming elections—the most important of which is defeating Donald Trump in November.

In Pennsylvania, tens of thousands of voters received their ballots in the mail after the election had passed. Baltimore residents had to wait more than a week longer to receive their ballots than residents of the other parts of Maryland. More than 1,000 voters in New Mexico were disenfranchised because their mail-in ballots arrived too late to be counted on Election Day.

In Georgia, tens of thousands of voters had yet to receive their ballots by mail on the day before the primary election, and more than 10% of in-person polling places in the state had been closed, forcing many voters to wait for hours in line at those sites that remained open.

Unfortunately, in New York’s June primary elections, we saw more of the same—delayed or missing ballots causing the disenfranchisement of people unable to leave their homes due to health concerns; polling places closed or moved without explanation; lifelong Democrats told to submit an affidavit ballot because their party status was somehow in question; voters forced to wait hours in line in the midst of a pandemic.

There were just under 800,000 absentee ballots sent out by the New York City Board of Elections and more than 400,000 absentee ballots returned by voters. However, we still have no clarity on the actual number of people who never received their ballots or received them late, nor the actual timetable of when the ballots were mailed out in the first place.

We also still don't know why the top voting Black polling place in my Assembly District (the 79th) was moved nor why several of our polling places were opened late nor why so many persons were only given presidential primary ballots nor why so many largely Black polling places have two-hour-plus lines due to insufficient equipment and scanners going down. Some may call these all innocent errors, but there's simply too much consistency to ignore, too much likely intentionality to overlook.

When the government needs to contact us to collect money, the mail system works seamlessly. However, from delayed stimulus checks earlier this year to now delayed ballots, we are not helping our fellow Americans to recover and exercise their right to participate in our democracy.

Simply put, it is unacceptable that untold numbers of Americans are being asked to literally risk their lives to participate in the electoral process because of the inadequacies of the vote-by-mail system and boards of elections.

I am proposing the following set of remedies.

First, all poll workers must receive non-partisan training, be treated as skilled employees with approved certification, and have no connection to any candidate or campaign. Moreover, the leadership and staff at boards of elections should always be independently appointed.

Second, there must be a public schedule that explicitly sets forth when ballots should be received by voters in the mail, ensuring some degree of government accountability. In addition, there must be a tracking system to notify voters of ballot distribution and arrival, just as there would be for any package purchased online.

Third, if someone is found to have participated in voter suppression, he or she must be immediately referred to the New York State Attorney General for investigation.

Fourth, we must ensure that devices at polling places are able to identify a voter who lives within that site's jurisdiction so that people are not unjustly turned away from their polling site or forced to submit an affidavit ballot.

Fifth, the public must be given transparency as to why a person is asked to vote by affidavit ballot or has had their ballot invalidated. My team has identified several hundred affidavit ballots that were initially deemed invalid, many for simply undemocratic reasons such as a person who is confirmed by the Board of Elections to be a Democrat had their ballot invalidated because they didn’t check a box for why they were voting by affidavit. What if the person didn’t know why they were being forced to vote affidavit or the poll worker didn’t actually have a reason?

Sixth, there must be emergency allocations for local boards of elections and postal services to have sufficient capacity prior to the election. In the event that legal action is required in the 15th Congressional District -- or elsewhere -- to review the election results, that election should not be certified until the legal action is resolved. This should be the standard across the board.

Seventh, wherever possible, a public hearing and approval process must be established prior to moving a polling site.

It pains me to think that this undemocratic process has occurred over the course of many decades. Anyone who has contributed to the intentional disenfranchisement and suppression of voters should be ashamed, as your silence has led to the voices of New Yorkers not being heard.

If you voted by affidavit or absentee ballot, you should demand an immediate answer as to whether your ballot has been deemed valid and counted in this electoral contest. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers are thinking right now that their vote was counted, but unbeknownst to them, and for some undisclosed reason, their ballot was in fact voided. We should not have to sift through countless reams of paper to discover that New Yorkers—especially those in low-income, Black and brown neighborhoods—are being unfairly disenfranchised and suppressed.

The reforms outlined above are necessary because these issues are not theoretical. A recent study found that Wisconsin’s decision to hold an in-person election in April led to a substantial spike in coronavirus infections. In other words, these election-related issues are a matter of life and death. If we’re going to offer the early and mail-in voting that we should, it must work, and work well, to ensure that New Yorkers and all American voters have their right to vote protected and ensured.

As I continue to cry and mourn the loss of Civil Rights icon Rep. John Lewis, whom I had the honor to meet several times and bestowed upon me one of his final endorsements, my spirit reflects heavily on one of his many profound sayings: "If you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have a moral obligation to do something about it." As we enter the fourth week after our election with so many unresolved problems, I'm writing this because we have a moral obligation to end the voter disenfranchisement and suppression that occurs across New York State and this country.

Countless numbers of our ancestors marched, bled, and died for the inalienable right to vote. We shouldn’t have to risk death to vote again.

***

Michael Blake is a member of the state Assembly and candidate for Congress in the Bronx. On Twitter @MrMikeBlake.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Federal Funding Up for NYPD, Down for Human Services

NYPD officers (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayor's Office)

Budgets, as the saying goes, reflect our values. Take a closer look at where the money goes – or doesn’t – and you can readily see our nation’s priorities.

This is perhaps never truer than during an economic downturn. At FPWA, we’ve examined the trends in federal spending for human services using our online Federal Funds Tracker. We know that since the Great Recession ten years ago, the federal government’s austere budgets have left human service programs in New York City deeply underfunded. Such policy choices have disproportionately harmed Black New Yorkers and other communities of color. Now, a decade later, the coronavirus pandemic is dealing another uneven blow to the same communities.

Our Tracker tells us where the federal money didn’t go. But what do we learn when we look at where it did go? What does the data reveal about our priorities and something more – our systemic biases?

As recent anti-police brutality protests offered hope of “arousing the nation’s consciousness” about systemic racism, police reform, and social injustices, we used the Tracker’s open data infrastructure to explore trends in federal funding for policing compared to human services.

We found that between fiscal years (FY) 2010 and 2019, federal funding for New York City’s human services fell by $344 million (8 percent) while funding for the New York City Police Department (NYPD) increased by $144 million (129 percent).

Driving this growth in federal funding for the NYPD is the ‘Urban Area Security Initiatives’ (UASI) – a formula grant that is intended to “protect against terrorism in high-threat, high-density urban areas,” but that some civil liberty, humanitarian, and religious organizations have identified as being central to the “acceleration of police militarization and lack of accountability.”

Nationally, $605 million was appropriated for UASI in federal fiscal year (FFY) 2020 – an increase of $25 million since FFY 2019, and $9.4 billion since the program was signed into law in the 2003 Omnibus Appropriations Act.

New York City has received a quarter ($2.3 billion) of all UASI funding. In FY 2019, the NYPD received more than $117 million for UASI, representing approximately half of the department’s federal funding. The vast majority of this funding supports NYPD’s ‘security/counter-terrorism’ program, while Housing and Preservation Development (HPD) and Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) receive a small slice each.

Subject matter experts in policing and counterterrorism and those with a better grasp of NYPD’s opaque budget will better understand how NYPD’s UASI funding is spent, the efficacy of the nearly two-decade-old program, and the extent to which other programs such as the Department of Defense’s 1033 program have militarized the NYPD. We do know, however, that the “nexus to terrorism” funding requirement in the UASI program has enabled police departments across the nation to acquire highly militarized weapons such as body armor, bayonets, automatic rifles, grenade launchers, armored vehicles, and surveillance drones.

These cast-off weapons from the Pentagon are intended to support counterterrorism efforts, but the resulting militarization of police forces is also used in the everyday policing of Black, Latino, and poor communities, the illegal surveillance of Muslim communities, and the escalation of police violence against protestors. In fact, the UASI program came under scrutiny following the weeks-long standoff between anti-police brutality protestors and heavily armed police forces in Ferguson, MO.

FPWA’s online Federal Funds Tracker tool visualizes trends in federal dollars for human services in New York City, but it also allows users to download trend data on federal grants that support all categories of spending. As policing in America is more closely examined, especially as experienced by Black Americans, these findings gives credence to concerns expressed by protesters, advocates, and policymakers who wish to see the budgets of police departments more closely scrutinized, and more dollars reallocated towards human services such as education, housing, mental health, and other social services.

Black Americans have been disproportionately harmed by each of the last decade’s crises and disinvestments from programs that improve people’s lives, while simultaneously confronting systemic racism that is present – and well-funded – today, such as militarized and discriminatory policing. As Congress begins preparing next fiscal year’s budget, it is encouraging to see bipartisan legislation that acknowledges the federal government’s role in the militarization of local police departments, but closer scrutiny will be required to truly address the full scope of budget tradeoffs that exacerbate racial injustices.

***

Derek Thomas is Senior Fiscal Policy Analyst; Matan Diner Fiscal Policy Fellow; and Gaurav Gupta-Casale is Fiscal Policy Analyst at FPWA. On Twitter @FPWA.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Exposing - and Ending - Police Lies

New NYPD officers (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography)

America is being confronted with a truth that Black communities have always known—cops lie. They tell big lies that send people to jail for life. They tell small, yet still extremely dangerous lies like the completely fabricated Shake Shack poisoning. Cops especially tell insidious lies to cover up acts of racial terror, as we witnessed with recent lynchings that were officially labeled suicide by the police. These lies are part of a broader system, culture, and practice of police violence, and just one more reason why we must defund the police.

Perhaps most disturbing of all is when these lies are used to absolve the police of murder. Elijah McClain, who died in Colorado police custody last year, had done nothing illegal prior to his arrest. Cops claim McClain was resisting arrest and reached for one of their guns, even though recorded evidence directly disputes that lie. The Louisville cops who killed Breonna Taylor told many inconsistent stories about the night they barged into her home and shot her eight times.

The ever-increasing count of murders by lying police still only constitute a fraction of the lies cops tell. Cops lie to justify violating constitutional protections and due process rights of Black and brown communities, and they do this with impunity. Ask any public defender and they will corroborate that cops lie. In fact, ask any police officer and they will also corroborate that cops lie, as they did with the New York Times—what cops have admittedly called testilying.

Similarly, New York City prosecutors often enable the practice of cops lying in order to convict people, regardless of innocence. In all five boroughs, prosecutors are maintaining internal databases of cops with credibility problems in court. These secret databases must be made public for transparency and accountability. At the same time, these secret databases only scratch the surface of the problem. A Gothamist/WNYC investigation in partnership with The Appeal found that New York City prosecutors consistently fail to document and disclose police dishonesty.

Most notably in popular culture, Ava DuVernay’s masterful television miniseries “When They See Us” illuminates the lies, corruption, and self-delusion of police and prosecutors alike. Yet, cops have occupied the moral and credibility highground for far too long, meanwhile Black and brown communities have been pathologized and vilified.

As public defenders, we bear witness to the lies cops tell to justify racist policing. Public defenders all across the United States have taken to social media in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement and calls to defund the police. Using the hashtag #CopsLie, The Black Attorneys of Legal Aid organized this digital campaign to show that the systemic racism and abuse within policing in America are not individual incidents and cannot be excused as aberration.

Nonchalant lying with impunity is ingrained in American police culture. We've seen police plant evidence, falsify documents, and lie while testifying under oath. They even blatantly lie in the face of contradictory video evidence. These lies are so prevalent that even journalists are reexamining their reliance on the police as sources.

Public defenders have inundated social media with firsthand accounts of police lying. Finda Yawah, a public defender in New York City, recounts when a “cop claimed my client tried to hit him on top of the head with a 40 ounce bottle. It was physically impossible due to my client’s severe medical issues and injuries to his spine before the incident.” Fortunately, the jury saw through the cop’s lies and found her client not guilty.

Public defenders routinely see the false reasons police give to arrest and detain by asserting, "He fit the description." Destiny Singh, a Black attorney and former public defender in Palm Beach, describes her personal experience with these racist lies in court. A cop, who claimed to witness her client committing a crime, is asked to identify her client. The cop “points to me. Then continues to describe what I’m wearing,” writes Singh. Singh’s client was later acquitted.

Police lies are entangled in police violence. Cops commonly lie to excuse their use of excessive force. Olayemi Olurin, a public defender from The Legal Aid Society’s Queens office, shared multiple stories. One of these stories involved a “teenage boy who officers lied + said threw a Capri sun on the ground,” so “they tased and beat him so many times he peed himself, was bleeding, had cuts running down his legs and couldn’t walk.” What would have kept this Black boy safe is to reduce contact between police and communities. Prison abolitionists like Mariame Kaba have explained: “The surest way of reducing police violence is to reduce the power of the police, by cutting budgets and the number of officers.”

Racist and aggressive policing, coupled with after the fact lies, have serious collateral consequences on Black and brown communities, from unemployment to immigration detention. Olurin represented another “young man who police arrested and charged with criminal trespass as he was entering his own home. The address he was accused of trespassing at was his home address listed on his ID and the paperwork provided by the officers themselves.” Yet, “the prosecution still refused to dismiss the charges for a couple of months and my client could not get employed because of the open criminal case.”

Law enforcement lies even shape public policy, like when New York rolled back bail reform earlier this year under the guise of public safety. Cops are using fear to fight reform. “The reality is the NYPD goes to great lengths crafting causation where there is none, misleading the public, and, yes, even lying to maintain the unmitigated, militaristic power they enjoy in the city,” said Marie Ndiaye, a supervising attorney in the Decarceration Project at The Legal Aid Society.

According to journalist Ross Barkan, the spectre of murders in NYC needs context. “There have been 176 people killed. At this point last year, 143 were killed. This is a spike, not an apocalypse.” In fact, back when Michael Bloomberg was mayor in 2012, “419 people were killed. We are in the midst of a once in a century pandemic,” and “NYC is NOT on pace for that.”

In an era of alternative facts, the amplification of #CopsLie stories reveal truth and give visceral meaning as to why we must defund the police. To defund the police is to reduce police contact with vulnerable communities, because policing is a part of the problem of violence in our society. As we begin to reframe what public safety means and the role of policing, we must also understand that defunding the police seeks to reallocate and redistribute resources from policing to institutions and services that promote healthy communities--like education, healthcare, and housing.

NYC is allegedly cutting $1 billion from its usual exorbitant police budget of nearly $6 billion, but activists have criticized Mayor Bill de Blasio and NYC City Council for shuffling funds to pay the NYPD through other agencies, like the Department of Education. However, problems with the criminal legal system is not a policing problem alone, other actors in the criminal justice system require significant changes as well. In addition to defunding the police, there are concrete steps that can be taken by prosecutors and judges in the meantime.

We need prosecutors to confront their own complicity in bolstering police lies, and proactively expose police abuse. Judges can also refuse to rubberstamp police testimony, throw out cases where police are caught in lies, and even sanction the cops who lie. If police knew that their lies would not only be called out by public defenders but also prevented by prosecutors and sanctioned by judges, we would see a drastic decrease in lying cops and the destruction their lies cause.

***

Rigodis Appling is a public defender and a member of the Black Attorneys of Legal Aid caucus at the Legal Aid Society. Jason Wu is a legal services attorney in New York City, and a trustee for the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys, UAW 2325. On Twitter @rigodis & @CriticalRace.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York’s Working Men and Women are Ready To Go Back to Work

Construction needs to boom again (photo: governor's office)

New York, and the nation, are recovering from an economic hit unlike any other in our history. It has been tough and now is the time to get back to work.

Let’s build our way out of the pain of the last several months with innovative, ambitious, and transformative projects that will put wages for working New Yorkers back into the economy and let our hard-hit state speed the healing by rebuilding our aging infrastructure.

Hard work is the backbone of our nation. Hard work is what gives us purpose. And, hard work is what the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers has always been, and always will be, about. We’re ready - and I know we’re not the only ones.

Fortunately, from both an infrastructure and economic development perspective, there are some large projects waiting in the wings that will make a real difference in the lives of all New Yorkers. Investment is needed in transmission lines, onshore wind, solar, hydro, offshore wind, and improvements at our ports – renewable energy projects will put the men and women of this state back to work.

The Champlain Hudson Power Express is one such project. The buried and resilient electric transmission line will create more than 2,000 construction-related jobs for New Yorkers, add millions in tax revenue annually to local governments that desperately need the funding and bring firm, green energy to New York City, satisfying the power needs of over 1 million residents for more than 50 years. The project will do this while reducing harmful emissions and helping the Governor and Mayor move towards a more renewable, sustainable future.

With construction set to begin in 2021, the Champlain Hudson Power Express will be the first of many significant green building projects to break ground. These green innovative projects are poised to create thousands of new jobs for our union labor force. There is a reason this project and other clean energy job generators are supported by business leaders across the state.

Reviving and rebuilding New York’s economy is imperative, and it starts with organized labor. We’re ready to build, whether it’s offshore or upstate wind and solar, electrification of New York City, or installing solar panels on the roofs of apartment buildings and schools. We’re ready to install car chargers and we’re ready to train the next generation workforce to build this new and exciting green economy.

The IBEW and all of organized labor are ready to turn these initiatives into opportunity. That’s what New Yorkers do. We are grateful for the leadership our Governor and the Mayor showed us during these last months. We can thank them by turning their green visions into action and jobs. And in doing so, turn their clean energy goals into clean energy realities.

We are ready to rebuild our great state. We are ready to build the Champlain Hudson Power Express and much more.

Let’s work together to move New York State forward.

***

Christopher Erikson is the Business Manager for IBEW-Local 3.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Toppling Statues, and Prisons

Sing Sing prison, 19th century (photo: New York Public Library)

Monuments of all kinds are facing renewed scrutiny as protesters, fueled by the police killing of Rayshard Brooks, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others, have taken to the streets in more than 140 cities. Statues that glorify and venerate slavery and slaveholders are coming down, with or without governmental approval, across the country. The sight of these prominently displayed symbols of brutality, inhumanity, and state-sponsored racism tumbling down inspires hope that there may also be a long-overdue reckoning for the United States’ centuries of devotion to white supremacy.

Now is clearly the moment for all to examine the monuments that clutter the landscape – not only those that honor the racist deeds of the powerful men enshrined in their statues, but those built of impenetrable walls that continue to enslave tens of thousands of people. And while few thought, up until a few months ago, that hundreds of statues could ever be questioned, protested, and pulled down, so, too, should prisons – repugnant monuments in stone – now be subject to the same critical scrutiny.

Just as those who tear down statues understand the historical contexts in which they were built and persist, so too do prison abolitionists share a perspective – they teach that prisons are borne of a larger system with roots in slavery, and envision a path forward to a society where such institutions no longer exist. The abolitionists dare to imagine a time when – as with other monuments to atrocity – they come down, stone by stone, brick by brick.

‘Progressive’ New York is home to several of the country’s oldest and most brutal prisons.

Auburn prison was built in 1818. It is the site of the first execution by electric chair and the namesake of the "Auburn system," a practice that placed people in solitary confinement and required physical labor performed under complete silence. Any objections were met with a whipping.

Sing Sing prison was built in 1826 with cells measuring 7 feet deep by 3 feet-3 inches wide. The men inside were forced to mine the land and produced marble used in the construction of Grace Church in Manhattan, New York University, and the New York State Capitol and United States Treasury buildings. Six hundred and fourteen people have been executed in Sing Sing’s electric chair.

Clinton Dannemora was built in 1844. In 1887, 60-foot-high stone walls were added to the prison. Those walls still stand. It is sometimes called Little Siberia owing to the cold winters and the isolation of the upstate area where the prison sits. Originally, prisoners were used to supply labor to local mines. Nowadays, people inside New York prisons work a variety of tasks for an average of 65 cents an hour and their labor generates about $50 million in annual sales that goes mostly to local governments. Clinton is the largest maximum-security prison in New York, with a staff that includes about a thousand correction officers and supervisors.

New York, like many other states, built the majority of its prisons in rural regions far from the urban areas where so many of the incarcerated live. This reality exists up to the present: every prison in the state built since 1982 is in upstate New York. The proliferation of prisons in isolated, distressed rural areas that suffer from a lack of industry and jobs is due to their elected officials vigorously lobbying for prisons as economic saviors. The relationship between the decline of the upstate New York economy and the prison construction boom of the 1980s is unmistakable.

In many rural communities, the entire economy revolves around the local prison. Prisons offer jobs for relatively unskilled members of the community with no relevant training or experience. Rural towns in upstate New York employ hundreds of locals to oversee thousands of outsiders. Add to the mix the racial imbalance—predominantly, if not exclusively, white officers guarding predominantly Black and brown men—and the potential for abuse is as clear as the ugly images conjured up of plantations and slavery.

It is this upstate/city, white/black, guard/prisoner dynamic that leads to so many of the prison abuses that have been exposed over the years. Whether due to lack of familiarity, understanding, and trust, or racial animus, intolerance, indifference or neglect, the predictable results are systemic mistreatment. Discrimination in housing and job assignments and inadequate access to medical and mental health treatment are endemic. Fully revealed these days is the long-existing abuse of what are euphemistically called "special housing units" or "isolation cells"—in other words, rampant and prolonged solitary confinement for thousands of people.

While it may today seem impossible to literally bring down the prison walls, to attach a rope around the turrets and pull them down, much can be done. We can begin to dismantle from the inside out by freeing the innumerable people who remain incarcerated solely to satisfy the criminal legal system’s unquenchable thirst for punishment. Countless people of color in prison remain there solely because of racism and white supremacy, hastily dispatched by judges to serve life behind bars.

So much seems permanent in the American carceral system. The ancient upstate prisons stand with their imposing walls as unyielding fortresses. The people inside feel frozen in time, confined by a system that defines them solely and eternally by an act committed years before. It all feels impervious to change.

Yet few believed just a few months ago that scores of people would now be in the streets toppling visible symbols of oppression and reclaiming public space. Few thought there would ever be a serious conversation about defunding the police. Structural change in funding and priorities is on the immediate horizon. The current uprising calls for overarching reckoning and rectification. There is no reason its reach cannot be extended to prisons.

We can tear down a punitive system that values interminable punishment and holds no space for redemption. Newly constituted parole and clemency agencies must see people in prison for who they are and understand why they were incarcerated in the first place. Thousands of people can be immediately released as we begin to finally address the crisis of mass incarceration that has decimated families and communities of color. And eventually the walls of the prison just might come tumbling down.

***

Steven Zeidman is a professor of law at CUNY School of Law. On Twitter @SteveZeidman.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

One Essential, Concrete Step to Redress Environmental Racism in the South Bronx

Transforming the South Bronx (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

Our country’s history has been fraught with issues that have disadvantaged communities of color, including unequal housing, education, health, food access, economic opportunity, and the chronic stresses of living with racial bias. Intertwined with these are a myriad of severe environmental justice issues.

Communities of color suffer disproportionately from air pollution from nearby waste facilities, industrial plants, and high bus and truck traffic on their thoroughfares.“Diesel trucks and diesel buses play a significant role in impacting the health of our communities negatively,” said Cecil Corbin-Mark of WE ACT for Environmental Justice. “For us, this is one of the ways in which environmental racism manifests itself.”

In New York, one of the hardest-hit communities is the Hunts Point section of the South Bronx.15,000 trucks a day transport products and service the Hunts Point food market, which sells food to the whole city. "Yet Hunts Point itself is a food desert,” New York State Senator Alessandra Biaggi points out. “Residents often do not have access to the fresh produce being distributed right in their neighborhood.”

Diesel trucks spew exhaust containing particulates, nitrogen oxides, and ozone, which damage public health. Exposure to them correlates with increased emergency room visits, hospital admissions, and premature death. It also correlates with higher mortality from coronavirus. The asthma rate among youth in the South Bronx is 13% -- almost twice the national average. Nationally, communities of color breathe 66% more air pollution from vehicles compared to predominantly white communities. To lower childhood asthma rates, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and lung cancer, pediatric health expert Dr. Philip J. Landrigan recommends replacing diesel buses and trucks with safer, non-polluting alternatives.

We know how to do that, and we should do it now. New high-performance natural gas-powered engines for medium- and heavy-duty trucks virtually eliminate the health-damaging pollutants in diesel exhaust and are widely available. They’re also much quieter than diesel engines, enabling residents to sleep better at night.

These engines can run on conventional compressed natural gas or, better yet, on renewable natural gas (RNG), made from the methane biogases emitted by decomposing food and other organic wastes. Instead of letting them escape into the air, where they trap heat and warm the climate, the biogases are captured and refined into RNG. According to the California Air Resources Board and Argonne National Labs, RNG is the lowest-carbon fuel available today. When made from organic wastes diverted from landfills, RNG also reduces the negative impacts on communities near those landfills.

Trucks equipped with these engines cost about $40,000 more than their diesel counterparts. But a new “Clean Trucks” program initiated by the New York City Department of Transportation is covering the incremental costs of gas/RNG-powered and electric trucks, so private and municipal truck fleets in New York can afford to switch from diesel to clean trucks. They will have no trouble procuring RNG to run them. Last year Clean Energy Fuels, the largest U.S. supplier of natural gas, opened a refueling station in Hunts Point that sells RNG exclusively. It also announced last year that by 2025 it will phase out fossil gas and supply customers with RNG only. Since RNG is ultra-low carbon, fleets that adopt it will meet or even exceed New York and Paris Accord emissions targets, not by 2050, but overnight.

Clean trucks won’t solve all environmental justice problems. But for the South Bronx and other communities disproportionately impacted by diesel haulers, they’re an important step toward justice. The trucks, fuel, and financing are all available and ready to go. What’s needed now is the political will to use them. That’s a matter of principle, a question of what kind of country we want to live in.

We have a lot of work to do to build a society where justice for all extends to communities of color. Part of that work is eliminating discriminatory exposure to pollutants, and making sure environmental justice communities are first in line to get the benefits of technologies like clean trucks and RNG.

***

Joanna Underwood is founder and trustee of the NGO Energy Vision. On Twitter @energy_vision.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Covid Crisis Has Made It Additionally Clear: It’s Time to End School Admissions Screens in New York City

Brandon St. Luce, the author (photo: Dulce Michelle)

Sunday, May 17 of this year, marked 66 years since the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate is inherently unequal.” Yet today, many of our nation’s public school systems remain both separate and unequal. Nowhere is this clearer than in New York City, where I attend high school.

For five years, Mayor Bill de Blasio has touted an “Equity and Excellence” agenda while maintaining discriminatory admissions requirements at hundreds of middle and high schools that exacerbate segregation and inequity.

While these admissions requirements, known as “screens,” are not new, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has confirmed their unfairness, with nearly a third of public school students not having access to a laptop or reliable internet access, both essential during remote learning and for any student who wants to do the out of school preparation necessary for getting into the most competitive screened programs in the city. It has also given us a chance to hit the reset button. Many of the metrics that selective schools have traditionally used to sort applicants will not exist for the cohort of students applying to middle and high schools in December.

Screens vary from school to school, but screened schools have a long menu of options to choose from. They can restrict admission based on a host of factors, including, but not limited to: grades, attendance, punctuality, state test scores, zip codes, portfolio assessments, interviews, auditions, and school-administered specialty exams.

No, I’m not just referring to the city’s eight specialized high schools, for which the state legislature controls admission to the largest three. I’m talking about hundreds of screened schools squarely under the jurisdiction of Mayor de Blasio and the New York City Department of Education.

Admissions screens, which use flawed measures of “merit” to sort students, wind up segregating us by race and class. System-wide, two-thirds of students are Black or Latino and about 75% are poor. But at 30 of the most intensely screened public high schools, only one-third of students are Black or Latino and just 40% are poor. The effect is undeniable.

For more than two years, my peers and I at Teens Take Charge have been calling for integration through the removal of these admissions screens. We have proposed alternative policies in meetings with city DOE leaders, including Chancellor Richard Carranza and his cabinet of deputies.

Throughout the last two years, we have run two campaigns, both centered around the idea of abolishing admissions screens. Starting with the Enrollment Equity Plan, we proposed creating thresholds in all schools to make sure that at least 25% and no more than 75% of each high school's incoming freshman class has passed middle school state tests. This year we began to advocate for an “educational option” (ed-opt) model of admitting students in every school. This is not a new model, and it has been proven to help schools accept a diverse pool of applicants, including in my school, Edward R. Murrow High School, which is the most diverse school in the city. We have research that shows how much this would help with the demographic disparities in schools, backed up by the DOE’s own data.

We have led rallies, sit-ins, and, most recently, weekly “strikes for integration” at school campuses across the city. These strikes got major news coverage and turned out nearly 2,000 students from more than a dozen schools, including Beacon, NYC Lab School, and Millennium Brooklyn, three of the most heavily screened high schools in the city.

Every city and school official we have spoken to has acknowledged that screens contribute to segregation in our schools. They thank us for our advocacy. They tell us they are working on a solution. But nothing changes. The only high-ranking official who has not met with us or responded to our proposals directly is Mayor de Blasio, who we believe has been the primary obstacle to removing screens.

He didn’t even respond to his own School Diversity Advisory Group’s recommendations last year to end all middle school screens, some high school screens, and the ridiculous Gifted-and-Talented exam for four-year-olds. In September, he claimed that he would spend this school year doing public engagement on the recommendations, but there has yet to be a single public engagement opportunity.

This school year has come to an end, with the latter part being spent online with varying degrees of success, and it is irrational and illogical why screens should exist for students applying to schools next year. The only reasonable solution for next year is to forgo screens altogether and allow student choice to be the number one factor that guides where students are matched.

When demand for a school is greater than the number of seats, applicants could be matched using an equitable method called educational option (“ed-opt”) that is already in use at hundreds of city high schools. This system admits a proportional number of students who are below, at, and above grade level, producing academic diversity — which often translates to racial and socioeconomic diversity as well.

Proponents of screens and competition, namely, the Parent Leaders for Accelerated Curriculum and Education (PLACE), argue that screens are fair, bias-free assessments of hard work. As a student who recently took the Advanced Placement exam for U.S. History, I see a correlation in the way PLACE leaders talk about admissions screens and the way white folks in the Jim Crow South talked about literacy tests and poll taxes.

Low-income students and other vulnerable student populations are inherently punished by screens. Up until the pandemic, hundreds of thousands of New York City students did not have laptops or home WiFi, yet the high school admissions process has shifted entirely online and many screened schools require students to submit information or assignments online.

Then there are students like Jude, a 13-year-old at “one of the most competitive middle schools in the city” who recently started a petition to preserve the use of screens. Featured in a New York Post article, he is described as a “longtime Kweller Prep student.” Kweller Prep is a private tutoring company that charges thousands of dollars for its services, which include helping middle schoolers get into screened and specialized high schools. I’m sure Jude is a hard worker, but so are the thousands of other students across the city who cannot afford private tutoring.

To be sure, students like Jude and the parent leaders of PLACE are not our opponents. They are simply playing by the rules that Mayor de Blasio sets. And for far too long, those rules have allowed privileged students to cluster in a relatively small number of schools, bringing their social capital, PTA donations, and political savvy with them.

At a recent briefing, Chancellor Carranza gave us reason for optimism when he stated, in response to a question about next year’s admissions, that he and the mayor “will not penalize students in any way, shape, or form because of circumstances out of their control.” That’s exactly what screens do: penalize students for things outside of their control.

On April 16 of this year, Caranza also stated he would not allow “anyone to say ‘when we go back to the normal,' because the normal was never good enough for our kids. The normal meant some were privileged some were not.” The problems with screens have been identified by those who can create monumental change, yet their policies continue to benefit the most privileged in the city.

In the wake of this pandemic, Mayor de Blasio, Chancellor Carranza, and the Department of Education have an opportunity to shed New York City’s distinction as one of the nation’s most segregated school systems. This is the moment to start building the fair, integrated school system that was promised to us 66 years ago -- a system that gives every student the opportunity to thrive.

***

Brandon St. Luce is a junior at Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn and co-leader of the policy team at Teens Take Charge, a student-led organization that advocates for educational equity in New York City schools. On Twitter @TeensTakeCharge.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How E-Scooters Will Keep New York City Running During the Pandemic and Beyond

E-scooters in use (photo: Marat Mazitov)

In June, the New York City Council signaled a major shift in policy when it voted to allow people to use e-scooters on city streets. The Council legalized the private use of e-scooters and e-bicycles across the city and announced plans for a shared e-scooter pilot program that will allow e-scooter companies to operate in all boroughs besides Manhattan.

The timing could not be better. Workers, including health-care and delivery workers, require sustainable, flexible options for navigating around the city. As the recent surge in bicycle sales suggests, people are feeling safer using individual vehicles that allow for social distancing. E-scooters and e-bikes can help us ease back into public life without adding to citywide gridlock.

Before the pandemic began, traffic congestion in New York City was at an all-time high. According to the New York City Department of Transportation, vehicle registrations were increasing citywide while freight traffic and home deliveries also continued to rise. The only way to avoid the looming “carpocalypse” is to support transportation options that get people out of their cars.

E-scooters and other forms of micromobility offer cities like New York a natural complement to the transit services they already provide. And during a time when confidence in transit has tanked, these new transportation options have become even more important. To rely on shared e-scooters, New Yorkers will need access to a well-maintained fleet of vehicles that are waiting curbside.

Over the past three years, cities across the country have been working out the kinks of shared e-scooters and establishing programs that improve safety, equity, and sustainability. While local conditions vary, all successful programs have one thing in common: a requirement for accurate and complete data. It’s critical that the city first define its key use cases and success metrics so they can be measured against real-world outcomes. These goals should be shared with New Yorkers so they can see the impacts of e-scooters for themselves.

There’s no question that safety should be the top priority. While early data indicates that scooters are much safer for our streets than cars, there are still things cities can do to prevent injuries. First, city officials should take a look at streets where riders are more likely to ride on sidewalks because of narrow streets or other impediments. They can address those concerns by building out protected micromobility infrastructure, like bike lanes.

In addition, parking corrals reduce sidewalk clutter and help eliminate trip hazards for walkers. No-parking zones at the end of a block that accommodate clear sightlines or fire hydrants are great locations for e-scooter corrals since they do not require the removal of any street parking.

One aspect of new transportation services often overlooked is data privacy and security. Imagine, for example, if government could trace trips to a protest back to the house or apartment building where they began. The unsettling truth is that in many cities, they can. In California, the use of e-scooter data has even led to a Fourth Amendment lawsuit from the ACLU.

New York City must make a commitment to approach data privacy differently, by collecting the minimum data required to ensure the city is able to measure the efficacy of the program against goals. In particular, city officials should commit to never collect data that contains the precise location data of individual riders’ trips. Without a guarantee of data privacy, many would-be riders may think twice before hopping on a scooter.

The decision to welcome e-scooters to the streets of New York has huge potential to change the way New York City residents get around the city during the pandemic — and for years to come. If implemented properly, e-scooters and e-bikes are likely to become as embedded in the city’s character as the yellow cab. If implemented poorly, they may just end up in the bottom of the East River.

***

William Henderson is CEO of Ride Report. On Twitter @RideReport.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

It’s Time for New York City to Build More Beaches, Including in Manhattan

New York City beaches are often quite popular (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

If you ask Amanda Sisk how she feels about the beach, her answer is straightforward: “I love the beach! Even Coney Island. The beach is my favorite place. Water, any kind of natural water, it makes me feel good!” But having lived in Washington Heights for nearly a decade, getting to the beach is no easy task. It normally takes Sisk close to an hour-and-a-half to get out to Rockaway Beach via the A train. She prefers Rockaway Beach because there are separate sections for swimmers and surfers.

This year, as the city continues to battle coronavirus, officials have had to drastically reevaluate our city's beaches. While swimming will soon be allowed at all city-run beaches, activities like sunbathing are limited to crowds of 50% normal activity. Additionally, all of the city's public pools, which have historically provided a much needed respite from the sweltering heat, are currently closed due to COVID-19, with only 15 pools due to open on August 1.

As we continue to grapple with this crisis, one thing seems abundantly clear: it’s time to build more beaches — including in Manhattan.

New York City currently maintains 14 miles of beaches, traditionally from Memorial Day weekend through Labor Day. In 2018, more than 16 million people flocked to the city's beaches, with Coney Island and Rockaway Beach seeing the most visitors. That's an awful lot of people crowding on subways and buses to get to only a handful of places where you can really enjoy the sun and surf.

Luckily, we can look to other cities, such as Paris, for inspiration. Every year, the Paris-Plages turns the Bassin de la Villette into a beach resort, complete with sand and deckchairs. For people in the mood for a swim there are three pools right along the water, which are fed directly by the canals. Similar projects are being proposed in cities like Boston, Montreal, London, and right here in New York.

Kara Meyer is the Managing Director of Friends of + POOL, which is working to create a floating pool that would allow New Yorkers to swim in filtered river water right here in Manhattan. “We had this realization that we live on an island, surrounded by water, and none of us can access it for swimming.” Meyer notes that since the pandemic, there has been a renewed interest in opening up more public spaces in our city to residents. “No one has appreciated public space in New York as much as they do right now. We have this amazing resource at our fingertips, all around us.”

Creating more public space for recreation and relief from the summer heat is one step we can take toward the much larger goal of eliminating inequality in our city. While New Yorkers with means can escape to places like the Hamptons for a weekend, or even the entire summer, most don't have that option.

As we face the climate crisis, rethinking our waterfronts would also allow us to incorporate resiliency into the equation, building natural storm barriers, and reducing the urban heat island effect. The Hudson River Park Trust recently released new plans for a new 5.5 acre park, including a resilient beachfront, along the Hudson River. The area would be open to kayaking and canoeing, but not swimming, according to reports. There are similar plans underway along the Williamsburg waterfront.

Building a new beach will be no small task, but there are positive signs. Late last year, the city posted a request for expressions of interest on a project to build a “swimming facility capable of filtering the waters of the East River to enable safe recreational access to clean water.” Developing a workable system for swimming in the East River could be the first step in realizing this vision and in determining a feasible location for a potential beach.

New York City has done big things before, and as we’ve seen, where there is political will, there is often a way. Now is the time to be bold, and to reimagine our city’s waterfront, for ourselves and future generations.

***

Kim Moscaritolo is a candidate for City Council in Manhattan's 5th District. On Twitter @kimmosc.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Prioritize Schools - New Yorkers Demand a Real Plan for Our Students and Our City

students and schools in focus (photo: William Alatriste/City Council)

It can't be easy to be in charge of New York City schools right now, facing a triple threat of crises: health, financial, and educational. However, our city as a whole can't function without our schools open—until that happens, parents, guardians, and caregivers can't get back to work; businesses across our city can't rely on their employees; and many children can't get the educational, social-emotional, and nutritional support they need.

We know there are increasing numbers of unknown variables—the resilience of the virus across seasons, the emerging science around how it spreads in school communities, its specific effects on children, and the efficacy of our city's testing and tracing programs (just to name a few). And of course, it's paramount to ensure the safety of our children, teachers, staff, and families before we open school. Yet, beyond filling out standardized surveys from the New York City Department of Education and conflicting and vague announcements, the detailed discussion of whether, when, and how to open schools is invisible to most parents and families.

We need hope. We need leadership. We need the Governor, the Mayor, and the City Council to prioritize schools.

We demand a plan—one that’s ambitious, that’s given the resources to meet this moment, and that channels the innovation, creativity, and tenacity of our city to open schools safely and effectively for the benefit of New York City and its people.

1. The plan must show real leadership and transparency. Right now, families are kept guessing, and principals and school leaders are asked to make plans beyond their level of authority. The Governor, the Mayor, and the City Council need to offer real leadership to give direction to the Schools Chancellor and work proactively with the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), parent leadership, and every government agency to move this plan into action.

2. The plan must center on equity by respecting that all families are different. Some families can't send children to school due to health risks, some need to send children so they can go to their jobs or meet their family’s nutritional needs, many have IEPs, siblings, varying rigors with commuting, and differing relationships with or accessibility to technology. Every decision about how we school our kids needs to ask how we are offering agency and partnership to the families that are most vulnerable or have the highest potential to be marginalized. We need to make decisions that proactively counteract that marginalization. Any plan for the fall must ditch a one-size-fits-all approach to education.

3. The plan must lean in to small-group learning. For health reasons, we'll need lower student-teacher ratios. This is something every educator, parent, and caregiver has wanted for decades. To meet this need will require more space, more educators, and more flexibility and creativity with when and where instruction is occurring.

4. The plan must value education more than test scores. In a crisis, there can be a default instinct to go to what's measurable, such as standardized testing. We need to resist that impulse and invest in the social-emotional wellbeing of a student population that is facing real fears and, for many, traumas. The arts, guidance counselors, and mental and physical health are all more, not less, essential.

5. The plan must protect our privacy. Even as we push digital learning as a part of a blended model, our city must only enter into agreements with vendors that keep student data secure, refuse to allow companies to share or monetize data, and allow the right to be forgotten—so that students and families ultimately control how their data follows them.

6. The plan for our children must also be a plan for parents and guardians. It needs to support adults being part-time teachers at home by giving them extended family leave from work, protections around work schedules that flex to accommodate uneven structures of in-person and remote schooling, subsidies for supplemental childcare and enrichment, or other policy measures that allow parents and guardians to support their families without losing their jobs, job security, or financial wellbeing. The plan needs to account for staff, hourly, and independent contractor jobs alike.

There are physical structures, unemployed labor, sources of innovation, and willing and able volunteers all across our city that can be harnessed into a massive and ambitious mobilization to reopen and recreate our schools—if there's the leadership to mobilize them. Our city must tap every public and private partner it can reach to unleash our creativity, ferocity, and determination to make the 2020-2021 school year one where our students and families can safely thrive.

Signed:

Justin Krebs, District 15 Presidents Council / PS 39

Cateia Rembert, President Emerita, District 15 Presidents Council

Megan Butler, President of PS 39 Parents Association

Sara Thompson, President of PS 39 Parents Association

PS 39 Parents Association

Lisa Jackson Zelznick, former President - PS 130 PTA

Mel Boller, PS130 Parkside PTA Co-President

PS 146 Brooklyn New School SLT

PS 146 Brooklyn New School PTA

Amy Tate and Anna Catherine Rutledge, Brooklyn New School PTA Co-Presidents

Maria Fusilero, acting PTA co-president, PS 295

Julie Baron, Member of the PS 39 Executive Board

Laura Limonic, Parent at Community Roots Charter School D-13

Heather Volik, PTA President PS10

Miriam Nunberg, D15

Parents for Middle School Equity

Jackie Cazar, NYC Parent

Melissa Noonan, NYC Parent

Parent Leaders and Parent and Community Organizations can sign on here.

Any member of the public can demand the city and state prioritize a plan by signing on here.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

My Dream was to Become a Cop; Then Things Changed

Police recruits (photo: mayor's office)

Almost a month ago I graduated from John Jay College of Criminal Justice, the premier college in the country for leaders in law enforcement. Today, I am taking the first steps to find a job in social work, convinced, like many people my age, that keeping my community safe has to start with compassion and respect, not violence.

I started like many other students at the college, ready to become a cop. My cousin is a state trooper, and my grandfather served in the military in the Dominican Republic. I love my family's history, and I wanted to protect the neighborhood in the Bronx that we emigrated to in 2006 when I was a kid. I was going to be an officer that came from the same community I was going to serve. The type of officer who understood the hard life of Latino people in the Bronx, and was willing to put his life on the line. My parents were scared for me but supported my passion.

One of the first professors I had in the department of police science at the college was a retired NYPD captain, a role model for who I wanted to become. He would always tell us the struggles he faced trying to change the department's culture to emphasize community policing and end racism and brutality. He told everyone in his command that if they didn't like how he went about business, then he would get officers who would. He was an inspiration and cared about the community, but it never seemed like he won those arguments or changed the minds of many officers. He seemed to be an outlier in policing that was hard to find.

The more classes I took in policing and correction, the more I realized how bleak it is to try to reform policing from the inside. I wanted to be in a profession that did not make me question my values. I wanted to be there for the people without continually questioning my actions or the actions of those around me. I had a change of heart and decided to pursue a career in social work because it focuses so directly on helping individuals, families, and communities.

Growing up with immigrant parents and as a first-generation immigrant I learned the importance of support services. When I interned at the Northern Manhattan Coalition for Immigrant Rights, one of my duties was to conduct mock interviews with people preparing to take their citizenship exam. This is where I realized the impact I could have. Seeing the joy of those who passed their interview and became a United States citizen inspired me as much as taking a class from a retired police captain. Their reactions give me the motivation to keep moving forward to impact as many lives as possible in a positive direction.

My decision to pursue a career in social work was not connected to the protests to defund the police -- I made my choice long before this year and the events of the past weeks. I believe that the police need to be held accountable. There are many avenues that need to be explored, among them possibilities around defunding and adjusting the police budget in New York City.

Precious funding can be better allocated towards social services and the needs of underrepresented communities. As the conversation has picked up steam, I know firsthand that if our city supported groups like the ones I interned with or the hundreds of other under-funded social service organizations across the city, my community would be healthier, better educated, and happier.

When I was struggling over my career change, I remember a professor reassuring me that there are many paths where I could make an impact. "You could help so many people without having to be a police officer," she told me. It is with that mindset that I keep moving forward to the next chapter of my life. I am eager to do just that and support every one of my fellow graduates from John Jay and other institutions who are planning to do the same to help our city make much-needed progress.

***

Jerel Pena Duran is part of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice class of 2020.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.