Op-ed: If Lhota and de Blasio can agree on affordable housing, why can’t Congress?

New York’s recent primary elections made one thing clear: our next mayor will make a significant investment in affordable housing.

The Democratic candidate, Bill de Blasio, promises an ambitious plan to build or preserve 200,000 affordable units over the next eight years. Saying that “it's not right for the Democrats to own affordable housing,” Joe Lhota, the Republican candidate, supports a 150,000-unit housing plan created by a broad-based coalition we lead called Housing First!

Washington lawmakers might scratch their heads at this bipartisan consensus. But the proven benefits of affordable housing – safe, vibrant neighborhoods, lower healthcare costs and increased economic activity, not to mention jobs – are difficult for any mayor to ignore. In New York City, where a third of renters spend over half their incomes on rent and 50,000 people sleep in homeless shelters, investing in affordable housing is a no-brainer.

If only Republicans in Congress got the message. While the mayoral candidates promised to invest in housing, they can’t do it without federal dollars. Yet just about all federal housing programs are currently at risk. The current budget showdown, comprehensive tax reform proposals, and changes to the way Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac operate, together threaten the ability of Americans at all income levels to be safely and affordably housed.

{sidebar id=14}

The attack on federal housing programs is as mindless as it is mystifying. Housing remains one of the primary drivers of the national economy — and, like it or not, housing has rarely been built in the past 80 years without some sort of federal subsidy or tax expenditure.

And it’s not like affordability isn’t a national problem: according to a recent National Low Income Housing Coalition report, there are no longer any states where a full-time minimum wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rents.

The federal programs created to help low-income renters are an especially effective answer to these challenges. The Low Income Housing Tax Credit, sometimes used with federally-authorized tax-exempt bonds, is structured so that government only pays for success: private developers and investors take on the risk and receive tax breaks only after well-constructed buildings are maintained in top condition for years. Federal homeless programs save taxpayers enormous sums by funding supportive housing for individuals who would otherwise shuttle between expensive shelters, jails, emergency rooms and psychiatric hospitals.

{pullquote}The attack on federal housing programs is as mindless as it is mystifying.{/pullquote}

Despite tangible success, federal housing programs have been slashed by 30 percent since 2010, a loss of about $400 million for low-income New Yorkers. The most recent “sequestration” cuts have been particularly damaging to Section 8 rental vouchers, nearly half of which help the elderly and disabled remain housed.

Even LIHTC, the bipartisan bedrock of affordable housing finance created under President Reagan, is now under attack by many of his admirers. This tax expenditure accounts for about 50 percent of multifamily construction starts nationwide. If tax reform eliminates the housing credit, affordable housing will, quite simply, cease to be built.

Lastly, some Congressional proposals threaten the critical, but behind-the-scenes, role played by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and FHA in supporting not just single-family homes, but almost all financing of affordable multifamily rentals. There may be viable alternatives that allow a greater private sector role, such as those recently proposed by the Bipartisan Policy Center Housing Commission. But experts agree that solutions must address not just homeownership, but also affordable rental needs that are critical to the long term health of our communities.

As Washington lawmakers address the budget this month and consider overdue reforms, they need to leave party politics aside and make affordable housing a bipartisan priority, as it is in New York.

Three actions can be taken before the new year: 1) Exempt HUD homeless and housing programs from the sequester and further cuts, 2) Protect LIHTC and tax-exempt bonds in tax reform, and legislate minimum and permanent fixed LIHTC rates, and 3) Provide government guarantees for low-income rental housing in GSE reform, including a dedicated revenue source for the National Housing Trust Fund.

While low-income housing programs represents chump change next to the rest of the federal budget and other tax expenditures, the housing and economic activity generated by these programs is substantial. The tax credit alone has leveraged nearly $100 billion in private investment and creates 100,000 affordable units and 95,000 jobs annually. Given our nation’s extraordinary housing and employment needs right now, one would think members of Congress would agree on the importance of expanding affordable housing investment. Just like Bill de Blasio and Joe Lhota do.

Ted Houghton, executive director of the Supportive Housing Network of New York, and Todd A. Gomez, senior vice president, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, are co-chairs of the Housing First! affordable housing campaign.

Op-Ed: Rikers Island Prices

You’ll be surprised about one of the most expensive residential neighborhoods in New York. The average Manhattan studio apartment rents for about $1,953 a month according to a recent survey, but in this area it’s over $13,977.

Even in ultra-expensive New York City, you’d figure a building that costs an average $167,000 annually per person for a small “studio” and amenities has to be luxuriously swanky – but not so much. And it’s not on the Upper East Side, Midtown or even in Robert DeNiro’s trendy TriBeca. It’s more exclusive in some ways. It’s part of the Bronx but located on a 400-plus acre island on the East River.

That’d be Rikers Island, home to New York City’s biggest and most infamous jails complex.

Despite the island setting, it doesn’t offer much in the way of river views. The “studio” units are small, Spartan and offer little privacy. The building staff-to-tenant ratio, though, is amazing.

Last month, the city’s Independent Budget Office issued a brief report on the jail’s cost. On any given day it houses about 12,287 at an annual cost of $167,731 per inmate for a total of over $2 billion annually. About 93 percent of the guests are male; 57 percent black; 33 percent Hispanic, 7 percent white and 1 percent Asian.

“Budgets are moral documents” wrote Rev. Peg Chamberlin in the National Catholic Reporter recently. She was writing about a national budget gifting $10.17 billion in tax breaks and subsidies to highly profitable coal and gas companies while slashing billions to the country’s neediest by cutting safety net programs.

She could have been writing about spending $2 billion on jails while cutting food stamps and affordable housing programs, and condemning more than 50,000 people — four times more than are in Rikers — to homeless shelters daily.

The per inmate spending is extraordinary – far above any benchmark average for prisons or jails. Sometimes it’s difficult to translate a reduction in inmates to the per inmate cost, because the jail continues to operate with all the overhead costs involved. But Rikers is really a collection of jails in 10 buildings; eliminating whole sections or closing whole buildings would significantly reduce costs while still keeping a city jail system operating.

There are ways to reduce the jail population that would garner substantial public support. Like many jails, lots of the inmates are there awaiting trial. They haven’t been convicted of anything except being too poor to post bail. At Rikers, the “unconvicted” account for three-quarters of the population.

New York is one of only two states that automatically treat 16 and 17 year olds as adults in the criminal justice system. You really don’t want to know the other state (ok, it’s North Carolina). So 7 percent of Rikers inmates are 16 or 17 years old, in itself a questionable practice.

There’s also the issue of incarcerating nonviolent or first-time offenses. On any given day there might be 2,300 inmates at Rikers on drug charges; up to 100 on prostitution or loitering; and perhaps another 1,200 or more for other misdemeanors.

The operation of the jail isn’t without controversy. Rikers has a history of brutal violence and deaths. At least a dozen lawsuits have been filed arising from that history claiming guards used inmates as enforcers to maintain discipline or even for extortion. That's given rise to criminal charges and more than a few legal settlements. Some of the suits are still pending.

In terms of a standard metric for jails, Rikers has a high recidivism rate.

Let’s suppose the inmate population could be reduced by 1,000 and the cost by $167,000,000. What could that money do?

Many poor people in New York (last week the Census Bureau said NYC’s poverty rate jumped from 20.9 percent to 21.2 percent, translating to almost 1.8 million officially below the poverty threshold) still have little or no access to appropriate ongoing medical treatment and related services.

High-quality primary health care for people experiencing homelessness, who typically have multiple chronic health diagnosis, can be delivered for $190 a visit. A typical emergency room visit costs over $2,100. One hundred and sixty seven million dollars could provide 878,000 medical visits for poor people. That’s without adjusting for savings from unreimbursed emergency room visits and unnecessary hospitalizations avoided.

{sidebar id=14}

New York City has over 3,800 homeless youth but provides only 250 beds for them. Even if beds were as expensive as adult beds we could provide the extra 3,550 beds with more than $150 million left.

New York’s homeless shelter population has exploded since the elimination of rental subsidies to assist families move from shelter to permanent housing. Reinstituting the rental subsidy, a program that, despite all its faults, never cost more than about $1,000 a month per family, might move over 8,300 families into housing with $67 million left over. And that’s not considering either better outcomes and greater productivity of families that would be stably housed or the tax dollar savings from reducing the homeless shelter population where it costs $3,000 a month for shelter and services.

Imagine how far a share of that savings could go in needed expansion of our mental health services or drug and alcohol addiction treatment programs. Like the housing programs, it’s not inexpensive but the investment cost usually results in a major savings over time in avoided tragedies, greater productivity and less spending on emergency rooms, police and jail.

Care for the Homeless Executive Director Bobby Watts noted you could send three students to Harvard for what we’re spending on one inmate. The Blinker website claims we’ll pay more to house alleged drug offenders at Rikers a year than on all the New Yorkers in public housing. Food stamps cost around $1.50 per meal, so $167 million pays for 111,333,333 meals.

Good health policies, housing programs and the availability of treatment for those who need it don’t just produce better outcomes, they save money over time. It’s surely a more productive use of public resources than paying for jail, especially at a Rikers Island price.

Jeff Foreman is Director of Policy at Care for the Homeless. Follow him on twitter @JeffForeman2.

Op-Ed: Domestic Violence, Homelessness And The Next Mayor

Domestic violence is an issue that deserves the attention of New York City's mayoral candidates. It impacts every neighborhood in all five boroughs and is a leading cause of homelessness among New Yorkers; one-third of homeless families using the shelter system are survivors.

While shelters can provide an escape from abusers, they are only a temporary solution and do not afford survivors with the long-term security and supportive services they need. Today, most will end up still homeless, in risky situations or back in the homes of their abusers by the time their shelter stay expires.

Permanent and affordable housing for victims and their families is the only way to guarantee survivors’ continued security and place them on a path toward self-sufficiency. Yet, less than one percent of supportive housing in New York City is designated for domestic violence survivors and survivors are excluded from most other affordable and supportive housing referral systems.

It will be up to the next mayor of New York to address this crisis with the right kind of smart technical fixes to improve access to housing for survivors of domestic violence and implement modest investments to spur permanent affordable housing development.

{sidebar id=11}

Most low cost technical fixes can be accomplished through changes in City housing policy that affect how survivors can access different housing resources.

The current application process to obtaining affordable housing is lengthy, cumbersome, and inefficient, creating an unnecessary barrier between survivors and lifesaving resources.

Even though they are homeless, residents of domestic violence shelters cannot access HPD Section 8, HPD homeless set-aside units, or many supportive and semi-permanent housing options. HPD’s homeless resources should be made available to survivors of domestic violence using the Human Resources Administration shelter system.

In addition, the eligibility criteria for NYCHA domestic violence priority status relies heavily on criminal justice based documentation, yet most applicants from domestic violence shelters do not meet these criteria. In fact, in 2011, only 28 percent of domestic violence emergency shelter residents are even eligible for domestic violence priority. The application requirements should be expanded so as to not rely exclusively on criminal documentation.

By streamlining and expediting the application process for Housing Preservation and Development and New York City Housing Authority housing, survivors will have better access to a safe place to stay before exiting the shelter system.

These low cost technical fixes would go a long way towards improving access for survivors of domestic violence, but investments in spurring new development of permanent affordable housing are also essential.

Modest investments in permanent affordable housing would wean the city off of its $1 billion homeless shelter system and provide long-term and less costly solutions for survivors of domestic violence. The actual cost to house a family in a shelter for one year is $36,000, compared to an average of $12,000 per year in rent for permanent affordable housing. Yet, according to a 2007 report by the Independent Budget Office, the City spent $140 million on shelter for domestic violence victims compared to only $400,000 for permanent housing.

{sidebar id=14}

If the next mayor of New York designates a City agency to fund domestic violence support services in permanent housing, developers will be able to take advantage of capital funding and spur new construction of supportive housing for survivors.

The reality is that many survivors lack the work experience or education needed to support themselves and without some financial assistance, they are unable to afford an apartment on their own. According to New Destiny Housing’s 2012 report, Out in the Cold: Housing Cuts Leave Domestic Violence Survivors With No Place to Go, a household would have to make $24.68 per hour to afford a two-bedroom apartment in New York City, a significant amount of money for any single parent. The development of a rent subsidy program that included job training would ease this burden for survivors of domestic violence and place them on a pathway to self-sufficiency.

It will also be important for the next Mayor to explore bold new initiatives to tackle domestic violence. The introduction of a rapid re-housing program through New York City Family Justice Centers would reduce the use of costly shelters, provide services to domestic violence survivors who cannot access shelter, improve the long-term safety and stability of survivors, and save the City money.

Reducing domestic violence in New York City will require many solutions, from technical fixes to modest investments, and new initiatives. But a key factor to supporting low-income survivors and their children is providing them with permanent affordable housing. This will save the City millions of dollars that are currently spent on costly shelters and place the City on a path toward eradicating domestic violence while ensuring victims no longer have to choose between abuse and homelessness. This is a goal worthy of the next mayor of New York City.

Carol Corden is the executive director of New Destiny Housing, which seeks to end domestic violence by providing survivors and their families with permanent, affordable housing and supportive services that will guarantee their long-term safety and well-being.

Letter to the Editor: On Sal Albanese

Re: "Gotham Votes: Mayoral Candidate Sal Albanese Campaigns as Outsider” – September 6, 2013

We are writing in response to your recent article criticizing the League of Women Voters and WABC-TV for not including Sal Albanese in a televised mayoral debate.

The League of Women Voters of the City of New York has partnered with WABCV-TV and other news media over the years to provide voters with the opportunity to learn about the qualifications and positions of candidates who are serious contenders for city office. These debates have always been structured around criteria which are fair and equitable.

Since there are often more candidates for an office than can reasonably be accommodated in a one hour debate, we believe the voters benefit most when they can hear from candidates who have a possibility of being elected. Our long-standing criteria require candidates to demonstrate significant voter interest and financial support. Voter interest is determined by the data collected by at least two reliable polls. The financial support criteria are based on the candidate's meeting the minimum fund-raising requirement as established by the Campaign Finance Board for participating candidates. The CFB fund-raising threshold is used as a guideline whether or not the candidate is participating in the Campaign Finance Program. Self-financed candidates have never been denied participation in these debates if they meet the criteria. Unfortunately, Mr. Albanese’s campaign did not meet our criteria.

Mary Jenkins and Mary Lou Urban, co-presidents

League of Women Voters of the City of New York

Every Candidate Is for Affordable Housing, Whatever That Means

In one of America’s most expensive places to live, affordable housing has become a key issue in the 2013 New York City campaign. Every candidate has a plan.

But it’s not easy to decipher what affordable housing means, how candidates’ plans might work and especially where the funding would come from. The devil is always in the details.

“Affordable” means different things to different people. To advocates for people in poverty, it means housing extremely-low income families can afford. For many other New Yorkers, it’s housing affordable to middle income people.

What is “affordability,” anyhow? The government’s definition, from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, says housing is affordable if it costs a family no more than 30 percent of gross income. HUD’s definition includes rent and utilities, but for most programs it’s just rent, which usually doesn’t include electricity.

That means affordability for a fulltime minimum wage earning family is about $375 monthly. For someone pulling in a million dollars a year it’s $25,000 a month.

Income limits for affordable housing programs are calculated using “AMI" — the area median income — adjusted for family size. It’s pegged to a percentage of what the family in the middle of area income distribution, with half the families earning more and half earning less, makes.

Just to get a feel for it, HUD public housing projects and section 8 housing vouchers are typically set for extremely- to very-low income families earning no more than 50 percent of AMI. The city’s Low-Income Affordable Marketplace Program is for households with income up to 60 percent of AMI, or about $36,120 for an individual. Middle-income programs could go as high as 175 percent of AMI, or about $150,325 maximum for a family of four.

“Affordable” is very much in the eye of the beholder. Many New Yorkers make too much for some of the affordable housing programs and too little for others. For some, even the least costly affordable housing projects rent beyond their means.

Those with a robust skepticism about what candidates say at election time might translate “affordable” to mean affordable for people who vote, i.e., not so much for extremely-low, very-low or even just low-income families. They might question any promises if they aren’t tied to the money to pay for them.

With that in mind, we’ll review some of the things leading candidates have said about housing. Some candidates have given numbers.

City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, once a housing advocate herself, proposed a plan to create 80,000 new affordable housing units over 10 years, and a program to turn existing units into affordable housing. Public Advocate Bill deBlasio, formerly a HUD official, pledges to create or preserve 200,000 affordable housing units over 10 years. Comptroller John Liu promises 100,000 new affordable units over four years. Former Comptroller Bill Thompson pledges 120,000 units over eight years.

No one has a hard and fast way to pay for all the proposed new units, though more money from Washington is a popular, if unlikely, prescription.

Quinn did famously championed programs in Council along with general welfare chair Annabel Palma and Coalition for the Homeless Executive Director Mary Brosnahan, to open up more NYCHA housing and federal vouchers for people experiencing homelessness, and backs “permanently affordable” housing.

Running on the theme of “the tale of two cities” (the top 1 percent takes in 39 percent of all income, while “half of the city lives close to or in poverty”), de Blasio named funding of shelter beds for runaway homeless children as the one budget item he’d never cut. He talks about cracking down on “giveaways” to big developers without requiring adequate numbers of affordable units in return.

Thompson wants an inventory of city and other government land to use for development. He’ll lobby Albany for more control over rents.

Liu supports a Section 8-style city housing voucher for up to five years for 10,000 homeless families. Anthony Weiner wants specialized senior housing built on current NYCHA housing projects’ grounds and a “new tier” of affordable middle class housing. Former Councilman Sal Albanese says the Bloomberg administration didn’t create enough affordable housing.

The Democrats favor using mandatory inclusionary zoning and investment of some city pension money to boost affordable housing. They talk affordable housing far more than the GOP candidates. Some Democratic candidates favoring raising revenues from taxes on wealthier New Yorkers with incomes over $500,000, or $1,000,000. All now favor progressive tax raises if needed, though at least one started the campaign with a “read-my-lips-no-new-taxes” style approach. But most those revenues are already spoken for in other campaign promises.

Former Borough President Adolpho Carrion, the Independence Party candidate, hypes his Bronx record and wants to work with developers for more affordable housing.

The Republicans, former MTA Executive Joe Lhota, billionaire businessman John Catsimatidis and Doe Fund founder George McDonald, as well as Albanese, all appear to have endorsed a “Housing First” platform proposing 150,000 new affordable units. Lhota, the first on board, made big headlines doing it.

Lhota wants to use current post office property for affordable housing, but housing doesn’t make his website “priority” list at all. McDonald doesn’t necessarily endorse “government” affordable housing, but favors incentivizing developers to build 75,000 new small efficiency units near subway stops. The main Catsimatidis housing proposal so far is posting police officers 24/7 in many public housing buildings to fight crime. No Republican favors city tax hikes to pay for affordable housing.

All the candidates agree New York City has a profound and growing affordable housing problem. Statistics back them up. Thirty-one percent of city renters spend over 50 percent of their income on housing. HUD calls that “severely rent burdened.”

More New Yorkers are finding it difficult to afford city housing. The supply of affordable units isn’t keeping pace with demand. And city rents are increasing far faster than income.

That’s despite the Bloomberg New Housing Marketplace Plan, which promised and is about on target to deliver 165,000 new affordable housing units by fiscal year 2014.

The city constantly touts the plan as “the most ambitious” and “most extensive” affordable housing plan of any city in the nation. They deserve credit for it. But is it really a big deal that the biggest city – with a population nearly equal to the next three largest cities combined – has the biggest program?

Even as we add affordable housing we’re losing older affordable housing units under temporary programs that are expiring. Literally tens of thousands of affordable units are set to terminate during the next four-year mayoral term.

Whoever the next mayor is, whatever his or her commitment to affordable housing, it won’t be easy. Funding sources, especially federal funding, are shrinking, without relief in sight.

NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, one of the best research sources on the subject, recently issued a report noting “if the next administration seeks to expand the city’s commitment to affordable housing, that may also mean spending less on other important city priorities. Candidates should explain not only how many units they will produce or preserve and how much they will spend on housing, but also where those funds will come from.”

Jeff Foreman is policy director for Care for the Homeless. Follow him on Twitter at @JeffForeman.

Great House Party in New York City (But You're Not Invited)

There's a fabulous house party going on in town — but it's doubtful you're on the guest list. The rich and famous are celebrating the Big Apple housing market. What a boom!

"There's a lot of euphoria" according to Noah Rosenblatt of the Manhattan real estate web site UrbanDigs. New York City real estate news site The Real Deal labeled the luxury market "manic" and reported vacant land in Manhattan selling for up to $800 per buildable square foot, about equal to the square foot price of finished luxury condos just a few years ago. One expert said raw land at $800 a square foot would require apartment prices of $2,500 a square foot. To extrapolate, that's $2.5 million for a not-so-special 1,000 square foot apartment.

Brisk sales and rising prices have fueled residential real estate in the city's outer boroughs. Many Brooklyn neighborhoods are just as hot as Manhattan. A townhouse in Queens is under contract for $3 million, a record price in that borough. The Real Estate Board of New York says home sales outside Manhattan rose 13.4% year-over-year in the second quarter.

Across America, Standard & Poor's Case-Schiller index of residential sales reports, prices are up over 12 percent in the last year, and 2.5 percent just in April, the last month numbers are available for.

It's largely driven by supply and demand, the one economic concept we all understand. Available inventory is down — that's supply. Realtor Douglas Elliman, who issues quarterly reports, says supply in Manhattan was down 31.3 percent in 2013's second quarter compared to the same period last year.

Meanwhile, demand is rising.

No lesser authority than Frederick Eklund, star of Bravo's reality show "Million Dollar Listing", says, "You have a $15 million buyer in New York and can't find anything. It's chaotic out there." His co-star Ryan Serhart claims, "In Manhattan there's bidding wars everywhere."

{pullquote}The rich and famous are celebrating the Big Apple housing market. What a boom!{/pullquote}

The New York Times ran an article ("In a Seller's Market, Every Minute Counts") reporting it's a seller's market in New York City where "open houses are packed to capacity, bidding wars and all-cash offers have almost become the norm, and some listing prices actually rise, not drop, after a home is listed."

The Times quotes a broker saying "it's the kind of insanity you live for in this business" while relating the story of a two-bedroom, two-bath condo "aggressively" listed for $1.89 million earlier this year. Within 24 hours he had a flurry of requests to see the listing, so he raised the price to $1.99 million and scheduled an open house. In no time there were multiple offers. The sale finally closed, all cash, for $2.16 million.

The Times offered advice. Move fast. Don't wait for the open house. Forget about getting a deal. Be the first to make an offer. Make a bigger down payment (30 or 35 percent is the new 20 percent). Think about waiving contingencies.

So the law of supply and demand dictates prices rise. Party on!

Last month, Harvard's Research Center published a study with a cautionary title: "A Housing Recovery, But Not for All Americans." Steeped in the kind of detail and methodology you'd expect from Harvard research, the report essentially gave notice to most Americans and certainly most New Yorkers that if you're not already at that party you might not be on the guest list. It's not just that your invite went missing in the mail.

The report says there are 12.1 million extremely low-income renter households in America, but only 6.8 million housing units affordable to them. That's a game of musical chairs where most low-income families come up short.

About 37 percent of American households, 42.3 million of them, spend more than 30 percent of pre-tax income on housing — that's the federal government definition of "unaffordable" housing. Over 20.6 million households spend over 50 percent on housing, the definition of "severely burdened" unaffordable housing. In New York state, 22 percent of households fall in the "severely burdened" category.

The Harvard study documents "severely housing cost burdened" families spend 1/3 less on food, 50 percent less on clothing and 80 percent less on health care than an average family. To be clear, most of these households are working families. Seven of 10 households earning full-time minimum wage are in the "severely burdened" category.

More disheartening, it's getting worse. The law of supply and demand is working against poorer families. Renter households increased by 1.1 million in 2012, roughly equal to the entire growth of all American households, but the number of affordable apartments isn't close to keeping pace. April 2013 was the 34th consecutive month of rent increases averaging 2.5 percent annually. Meanwhile, the number of rental vacancies fell for a third year in a row.

If you don't believe Harvard, you can read the same story in the just published "State of New York City's Housing and Neighborhoods, 2012," from NYU's Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. Their annual housing report documents city rents are high and growing. Real estate prices in New York City fell 20 percent during the recession while rents increased by 8.5 percent in constant dollars. New York City's market rate rent in 2011 averaged $1,540.

Furman reports that from 2005 to 2011 median gross city rent increased 10 percent while median household income actually decreased. The average New Yorker's rent burden — the percentage of before tax income going to housing costs — rose from 29.9 percent to 32.5 percent, meaning average New Yorkers were renting unaffordable apartments by federal standards. An astounding 31 percent of New Yorkers spend more than half their income on housing making them severely cost burdened. In New York City, 78 percent of all low-income renters are officially "rent burdened".

Every Sunday many New Yorkers turn to the real estate section to read about "The Big Ticket", the most expensive sale of the week in Gotham. Invariably it's a 6,000 square foot, $28 million, sky-high penthouse with views and terraces. Or it's an historic home on a storied street with its own name at $35 million. There, and in a hundred glass enclosed condo buildings and blocks of brownstones in New York City, the grandiloquent house party is going on.

Most of us can read about it, but we're not really invited. Far more important than an open door, though, would be a commitment to more affordable housing. That would let more people throw a house party of their own.

Jeff Foreman is Policy Director for New York City's Care for the Homeless. Follow him on twitter @JeffForeman2

Op-Ed: Preservation Can Contribute To Affordability

In July, the Real Estate Board of New York went on a media blitz, touting their latest report blasting landmark preservation in New York City. This is part of REBNY’s ongoing campaign to paint our landmark preservation system, which covers a little over 3 percent of our city’s building stock, as “out of control” and “broken.”

In this latest attack, using Greenwich Village as an example, REBNY claims that landmarking makes New York unaffordable, and pushes the working and middle class out of our neighborhoods.

REBNY should tell that to the residents of Westbeth and 505 LaGuardia Place, Greenwich Village’s two largest affordable housing complexes.

Westbeth is the former Bell Telephone Laboratories, converted to subsidized housing for artists by Richard Meier in 1970. 505 LaGuardia Place, an affordable co-op designed by I.M. Pei in 1964, is part of a pinwheel-shaped trio of towers surrounding a giant Picasso sculpture.

Residents of both complexes are very committed to preserving the affordability of their homes, and both fought long and hard alongside the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation to secure landmark status for them.

In both cases, residents felt landmarking would protect the character of their surroundings and provide a bulwark against schemes to demolish their homes and replace them with something less affordable.

While they recognized that some obligations came with landmark designation, they saw that on the whole landmarking helped protect what they valued about where they lived (it should be noted that as a co-op, the residents of 505 LaGuardia Place are also the owners, who directly bear the responsibilities that come with landmark designation, while the owners of Westbeth, the non-profit board which runs the complex, also supported landmark designation).

REBNY should also run their argument by the residents of First Houses in the East Village. Built in 1936 as the very first public housing development in New York City, First Houses was landmarked in 1974. As in many New York City Housing Authority developments, residents often struggle to get needed repairs and maintenance.

But GVSHP worked with the tenants association to use the complex’s landmark designation to apply additional pressure for long-overdue repairs.

If REBNY was truly interested in examining Greenwich Village’s struggle with affordability, they would have also talked to residents of the far western part of our neighborhood. That part of our neighborhood, which until relatively recently mostly lacked landmark protections, also saw the swiftest rise in housing prices over the last two decades, and the most dramatic transformation from a mixed-use, mixed income community to home of the super-rich.

Quite contrary to REBNY’s assertions that landmark designation undercuts the affordability of our neighborhoods and stifles economic development, that un-landmarked area saw working factories and warehouses employing scores of people torn down and replaced by luxury high-rises that now largely serve as trophy homes for jet-setters who spend little time in New York.

Rather than increasing affordability, as REBNY would have you believe, the lack of landmark protections in this part of our neighborhood helped lead to a wave of ultra-high-end development the likes of which few parts of New York have ever seen.

Of course it might be easy to dismiss any claim by REBNY to champion the cause of affordable housing, since, in addition to dismantling landmark protections, the group has also sought to undermine the rent regulations that guarantee affordable housing for millions of New Yorkers.

And I have to admit, I take some personal umbrage with REBNY’s claim. In addition to serving as executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, I am also an affordable housing advocate, having sat on the board of several of our city and state’s largest affordable housing groups. I grew up in an affordable housing development in the Bronx, and spent most of my adult life in exactly the kind of affordable, rent-regulated housing as well.

In spite of this, I am glad that REBNY is shining a light on the relationship between landmarking and affordability, especially in an election year. I believe that a true examination of this relationship actually shows that landmark designation tends to help, not hinder, the cause of keeping our neighborhoods affordable.

But a true examination does not seem to be REBNY’s goal. In addition to alleging that landmarking causes unaffordability simply because neighborhoods like Greenwich Village are now both landmarked and expensive, REBNY also seeks to play upon the fear that landmarking adds prohibitive expenses to basic property maintenance.

While undoubtedly the extra layer of bureaucracy involved in landmarks regulation can add time and expense, REBNY’s approach is to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Rather than joining landmarks advocates in calling for increased funding for the Landmarks Preservation Commission (the smallest of all New York City’s public agencies) to streamline this regulatory process, REBNY has instead sought to create a climate that would starve the agency and dismantle its portfolio.

In spite of this fear-mongering, the reality is that almost all repair and restoration work to landmarked properties merely requires a staff-level approval from the Commission, which can typically be secured in less than 30 days. And while there are cases where the Commission may require slightly more expensive materials for renovation work, these are often investments which pay off in the long term, with more durability that helps protect buildings from deterioration.

{sidebar id=14}

What landmark designation also sometimes does, however, is create hurdles to developers trying to force long-term tenants in less expensive apartments out of their homes — which may be why groups like REBNY are so opposed to landmark designation.

For example, the East Village has seen a spate of “rooftop additions” where new owners seek to build additional floors on top of buildings while residents are still living there. Tenants frequently claim that the construction is aimed at making life intolerable and forcing them out, and it often succeeds in doing just that. But in landmarked districts, such additions are harder to build, and much less likely to be approved.

Similarly, developers sometimes use the “demolition clause” to get around the rent regulations that allow long-term residents to stay in their homes at relatively affordable rents. One of the few ways in which a developer can remove a rent-regulated tenant from their home is to demolish the entire building. But in landmark districts, such demolitions are rarely allowed.

Listening to REBNY, you would think that developers are regularly thwarted from constructing new affordable housing in places like the Village due to landmark regulations. In fact, quite the opposite is true.

An enormous percentage of our neighborhood’s remaining affordable housing stock is located within its landmark districts, which helps protect it from some of these more unscrupulous practices. And, in my 20 years of working on both landmark and affordable housing issues, I have yet to encounter a single example of an affordable housing development that could not be built due to landmark regulations.

By contrast, I know of many cases of affordable housing conserved or developed within preserved buildings, often using tax breaks and financial assistance available specifically for the re-use of historic buildings. Even without these incentives, re-use of existing buildings is often cheaper and more efficient than new construction, to say nothing of more environmentally responsible.

So while landmark designation may not be the answer to our city’s affordability crisis, it is certainly not the cause of it, as REBNY would have you believe.

Landmark designation provides a means to preserve the character of historic neighborhoods in all five boroughs, many of which currently face tremendous pressure, and in all demographic and socio-economic strata. Landmark designation does not directly regulate affordability, and its application can certainly have different impacts in different circumstances. But more often than not, I believe, landmark designation can help the cause of affordability.

Because it’s not just in the Village that landmarked buildings shelter a diverse range of people and businesses, including long-term residents who have put down roots and aspire to stay permanently in their communities. Landmark designation, in helping to preserve the buildings these residents and businesses call home, give them a fighting chance to stay as well, and can help ward off some of the more pernicious means by which they can be forced out.

Without landmark protections, these buildings are rarely if ever demolished to make way for more affordable housing or cheaper retail space. Instead, they are almost always lost to new luxury housing, usually with retail space for chain or big box stores, not small mom-and-pops.

This is one of the reasons we are seeing neighborhoods clamor for landmark protections throughout the city, from Bedford-Stuyvesant to Bay Ridge, Ridgewood to Richmond Hill, the South Bronx to Staten Island.

They are not doing so because they want to make their neighborhoods unaffordable. They are doing so because they want to preserve and perpetuate what they love best about the communities they call home.

Figuring out how to maintain the affordability and protect the character of our neighborhoods is among the most pressing issues facing our city this election year. Scare tactics and false equivalencies but forward by REBNY that mask hidden agendas are not the way to find solutions to these serious challenges.

A thoughtful examination of the facts is. And I believe the facts show landmarking and affordability are not only compatible, but more often than not, go hand in hand.

Andrew Berman is executive Director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

Creating A City For All Ages: A Roadmap For Mayoral Candidates

The next mayor will be responsible for 1.4 million people over the age of 60 — a population larger than most United States cities. New Yorkers are living longer. Seniors vote. What should be on the minds of candidates?

For the first time in its history, the city will see a 45 percent increase of older adults by 2030.

Baby boomers began turning 65 in 2011 and will begin turning 70 in 2016 — during the term of the next mayor. The over 85 is the fastest growing segment of the city’s population. Older New Yorkers reflect the diversity of the city’s population as over 50 percent come from minority groups. Many seniors financially struggle with one one out of there living in poverty. There are also endless opportunities for using their life experience in positive ways.

{sidebar id=11 align=right}

The next mayor needs to navigate this population tsunami with careful citywide planning. Older New Yorkers must be included as major stakeholders and not excluded as they often are. As a city, we must raise the bar on addressing ageism.

How does the next mayor take the helm and what are the issues?

Council of Senior Centers and Services has developed an extensive candidates questionnaire designed to address issues impacting the lives of older adults. Responses can be found at www.cscs-ny.org.

On July 11, over 400 seniors and others packed the first mayoral forum focusing on older adults. They came from over 80 neighborhood programs across the city. Five candidates attended: Democrats Sal Albanese, Bill de Blasio, John Liu and Anthony Weiner; as well as Republican John Catsimitidis.

It was a great opportunity for those who came to answer an array of questions. It was a lost opportunity for those who did not come.

The audience was engaged and serious — clapping, cheering and even booing at one point. They will talk about this with their friends at senior centers and other places, their families, and neighbors.

CSCS’ alert and the video of the forum let thousands of New Yorkers know what happened.

A broad array of issues was covered:

• Department for the Aging funding for community based services

• Elder abuse

• Retaining and building affordable housing with services for older adults, rent regulation and SCRIE

• Hunger and food insecurity and the under enrollment of older adults in the SNAP/food stamps program

• Public transportation – user friendly mass transit system and improving Access-A-Ride

• Emergency preparedness and disaster response for older adults

• Cultural sensitivity to elderly immigrants and LGBT seniors

Time did not allow for questions regarding supports for family caregivers, mental health services, and the increase of those with Alzheimer’s. These areas are covered in our questionnaire.

The next mayor needs to provide a variety of means to ensure the economic security of older adults. The platform presented in our questionnaire and at the forum is a roadmap to making the city a good place to grow old. Aging with dignity is what we want for ourselves, our loved ones and all New Yorkers.

Bobbie Sackman, director of public policy at the Council of Senior Centers and Services, can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. CSCS’ mission is to champion the rights of older adults to make NYC a better place to live.

A Public Policy to Put Homeless Kids on the Streets

Suppose there were 3,800 children living on their own or without homes in New York City, but only 250 shelter beds for them. According to the nonprofit providers of the city's shelter beds, some of those kids — sometimes hundreds and hundreds of them — are turned away each night because there's not enough space for them.

How would we address that?

One answer would be to cut the number of beds and turn even more homeless kids back to the street.

And that's exactly what had been proposed for the 2014 city budget by cutting $12.6 million to $7.2 million and reducing beds to an estimated 90.

Let me quickly reassure you that no cut was actually adopted. But that issue brought me to a rally last month on the steps of City Hall to talk about helping runaway and homeless kids.

It was an unforgettable rally. What moved me weren't the well-reasoned arguments and statistics of advocates like Jennifer March-Joly and Caroline Nagy of the Citizens Committee for Children of New York. Not even the heart-wrenching providers' stories of turning kids away each day as they ran out of beds — and can you imagine how that feels for the people who devote their lives to serving kids in need.

It was the kids.

The kids, all under 18, spoke about life on hard streets and having a safe place to lay their heads. But mostly they talked about the other kids, the ones on the streets who hadn't found a bed, "the turned away kids."

One young woman [girl] struggled to ask that those other kids get a safe place, too, questioning aloud if she was greedy to be asking. Another boldly said everyone should be able to get a bed and at least one meal a day. One. That teenager concluded, "I hope I'm not asking too much." Of course, he was asking for far, far too little.

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

They're just kids. Most of them either escaped from sexual or physical abuse or got thrown out after "coming out" about a sexual orientation their parents wouldn't accept. They seemed scared and bewildered. Mostly they're hurt.

A recent Covenant House and Fordham University study of these runaway and thrown-away kids in New York City found 25 percent had either been "trafficked" in the illegal sex industry or involved in "survival sex" — trading their bodies for a place to stay or a meal. On the streets they're at constant risk of mental and physical health problems, especially violence or sexually transmitted diseases like HIV.

Jane Bigelsen, director of the Anti-Human Trafficking Initiative for Covenant House, told how pimps approach the turned-away street kids. He said they say, "The shelters are full. Where are you going to go? Why don't you come with me?"

Councilman Lew Fidler, the longtime, staunchest supporter of runaway and unaccompanied kids who will be term-limited off Council in January, asked, "For crying out loud, can't we find a shelter bed for every young person who needs one?" Fidler, too, said the kids who can't find beds are "forced in one way or another to sell their body, their soul, their dignity."

Providing beds for unaccompanied minors isn't without controversy. There are critics opposed to providing "opportunities" for kids to runaway, or who would place them in more restrictive institutions or other forms of government care.

Current providers do frequently reunite runaways with their families and they offer high-quality and varied human services and counseling. Many of the kids, who now self-report to these shelters they trust say they would avoid more restrictive programs. Surely this debate can't be between theoretical government care programs and non-existent shelter beds, while thousands of kids remain prey on the streets.

There is a more fundamental point. American public policy hasn't been kind to our children.

The poorest age group in America is children under 18. The Census Bureau reports 22 percent of children, over 16 million of them, lived in poverty in 2011. Kids make up 24 percent of the U.S. population but 34 percent of those living in poverty.

Over seven million children live in "extreme poverty," defined as living in a household with income less than half of the poverty level. That's currently below $11,511 annually for a family of four.

One in four (25.1 percent) of American children under 5 years of age live in poverty. It's one in three for black or Hispanic kids.

UNICEF recently published an alarming study of child poverty in the world. In one chart, they ranked developed countries on a measure of poverty they devised tracking the percentage of kids in families living below the national median income. Of 35 countries the U.S. came in 34th, beating out Romania. Finland ranked highest, but we also lost out to Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Estonia, Slovenia and the Czech Republic, among others.

The statistics in our city are grimmer. The city Health Department reports 20 percent of kids between 6 and 12 — about 145,000 city kids — struggle with mental health issues. Half of third graders read below grade level. One in every dozen babies born in New York City is underweight.

As sequestration cuts spending, and an austerity policy gnaws at the American safety net and our social compact to give all kids a chance, the programs being hurt the most are disproportionately programs for kids.

Sequestration has brutalized head start programs, cut childhood immunizations and federally funded child care. Cuts to the federal Maternal and Child Health programs will stop millions of families in need from getting access to that service over the next decade. The proposed SNAP food stamps cuts being debated in Washington would literally take food out of the mouths of babies.

We need a national movement to raise all children out of poverty. But let's start with an effort to make sure all the kids have a safe place to rest their heads at night. And maybe we can splurge for two meals a day.

Jeff Foreman is Policy Director for Care for the Homeless. Follow him on @JeffForeman2

Op-Ed: A Tale of Two New Yorks

It is the best of times; it is the worst of times. New York has always been a city of both wealth and poverty, but never more so than now. It’s easy to spot the wealth – getting a clear view of the poverty is a bit more complicated.

A recent WealthInsight study sets the number of millionaires in Manhattan at 389,100, defining millionaire as someone with net assets over $1 million excluding their primary residence. America's second city for millionaires is Los Angeles, with a mere 126,000. More breathtaking, Manhattan boast 70 billionaires — more than any other city in the world (Moscow is second with 64; L.A. has just 19). Why not in a city led by the world's wealthiest mayor, reportedly worth $27 billion?

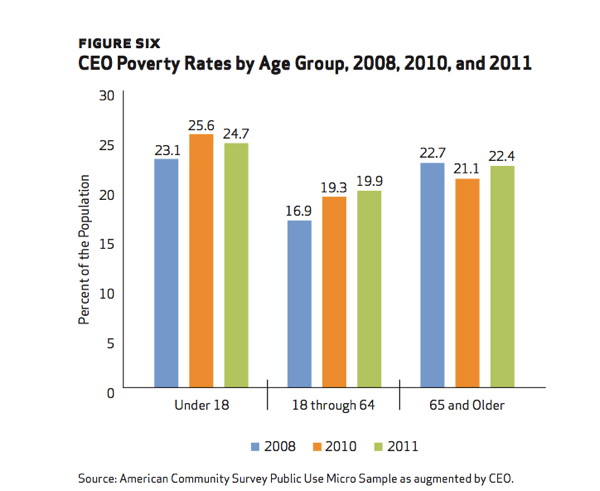

The Center for Economic Opportunity, a city project initiated by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, recently issued its "Poverty Measures Annual Report" for the city with statistics through 2011. It's an interesting read because the CEO uses a poverty measure different than the official federal poverty rate.

The official rate produces a national poverty level without regional adjustment. The CEO measure adjusts for variations in area housing costs and it's based on National Academy of Science criteria reflecting what families actually spend on necessities, but also includes the value of noncash benefits like SNAP payments (food stamps), free or reduced rate school meals, Home Energy Assistance, housing assistance and so on, as income.

The official 2011 federal poverty rate in New York City was 19.3 percent , though it's now 21 percent . The 2011 CEO figure was 21.3 percent , a full 2 points higher. It was worse for hard-hit subcategories like non-citizens (28.9 percent ), kids under 18(24.7 percent ), single parent homes (30.9 percent ) and the Bronx (26 percent ). The poverty rate for kids in single parent homes was 34.7 percent . Asians CEO poverty rate was 26.5 percent and the rate for Hispanics was 25.3 percent .

Now in the throes of sequestration and a public policy of austerity, assistance resources for poor people have generally gone from few to really meager. There is Temporary Aid for Needy Families, but only for families with children and limited to an aggregate five years over a person's lifetime with the requirement that family adults work for the benefit. New York has a Safety Net Assistance program for those who have exhausted their lifetime federal benefits, but that generally has a two year limit for regular cash benefits.

New York City's safety net for homeless families in shelters used to include a priority for public housing or Section 8 vouchers, but that generally stopped after 2004, replaced by a transitional rent subsidy program which was also eliminated in April of 2012. Now the only generally available program for moving most homeless families to permanent housing is a job. That's if you can find one and if it pays a living wage.

New York's Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness estimates unemployment among homeless families at 57 percent. In fact, ICPH's 2011 survey of homeless parents found 68.5 percent unemployed.

Sequestration has foreclosed on some of New York City's tools. It visited Section 8 housing cuts on the three agencies issuing vouchers in New York City, meaning 5,000 planned housing vouchers won't be issued. New York City's Housing Preservation and Development Department lost $36 million and plans to cut 1,000 vouchers. "The real problem is," HPD Commissioner Matthew Wambua says, "these are our neediest tenants, the ones who cannot even afford the units in our developments."

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

He notes 32 percent of HPD's vouchers go to elderly renters and 44 percent to disabled people. Still, to avoid eliminating even more vouchers Wambua plans to reduce subsidies for many current Section 8 recipients, with reductions to subsidies as high as $400 a month.

New York City's Housing Authority and the state Department of Homes and Community Renewal both issue Section 8 vouchers in the city and have suffered sequestration cuts. They too won't issue a large number of planned vouchers.

The recently passed city budget does add some NYCHA resources, but not enough to overcome the public housing repair backlog, and certainly not resources to make up for sequestration cuts.

Even having a job isn't necessarily a get-out-of homelessness free card.

Most homeless people who find employment work in low wage jobs in fast food, child care and personal services, security work or retail sales. Fast food and security jobs often start near minimum wage. Even work in the healthcare-childcare and personal services fields pay an annual median income of $22,980 for homeless heads of household in New York City, according to the ICPH survey.

The federal poverty level for a family of four is $22,811, though the CEO sets New York City's poverty level at $30,945. Among the 22 percent of homeless families with a fulltime worker, most remain in poverty. Even among all New York families with two fulltime workers, 4.9 percent are in poverty.

A better way to understand poverty in New York City is to consider income inequality. Since 1967, the U.S. Census Bureau has used a measure, the Gini coefficient, sometimes referred to as the index of income correlation, as a measure of income inequality. It's a ratio of income dispersion comparing the median income of the highest quartile (20 percent ) to the lowest quartile median income. The higher the coefficient is, the greater the income inequality. If all families had the same income, the coefficient would be 0. If one family had all the income and the rest had none, it would be 1.0. In 1967, the first year the Census Bureau used it, the national Gini coefficient was .34. But in 1969, 1970 and again in 1974 it was as low as .326

The Census Bureau's 2011 national Gini coefficient was .477. But for Manhattan it was an extraordinary .601, the second highest number for any county in America. If Manhattan were a country, its Gini coefficient would be among the highest in the world — meaning the greatest income inequality — including most sub-Saharan nations, Middle Eastern emirates and third world countries. Manhattan's median income for the top 20 percent of earners was $391,022, compared to a $9,681 median for the lowest 20 percent. Top earners made better than 40 times what the bottom fifth did.

New York really is a tale of two cities: a rich gloriously city and a desperately poor one. The two cities cover the same geography but offer very different views. The ICPH study has a dire warning: "If changes are not made to the current system, family homelessness will only continue to grow" from its already historic highs.

All of the 21 percent living in poverty in America's richest city — nearly 1.75 million people — are at risk of homelessness if something isn't done about it.

Jeff Foreman is policy director at Care for the Homeless. Follow him on twitter @JeffForeman2.

Op-Ed: Stop-And-Frisk From A Mother's Perspective

I often wonder if I have what it takes to raise my black son in New York City.

While concerns about navigating public school application processes and scheduling play dates are common topics among parents, what often goes unspoken is something far more important: the unique challenges that come with parenting a young boy of color in New York City.

With nothing promised for young blacks and Latinos other than low expectations, street violence, negative peer influences and persistent police suspicion, how do we make sure that that our sons grow up safe and thriving? One step is putting an end to stop-and-frisk.

The New York City Police Department’s stop-and-frisk policy and all of its implications on crime and race are now at the forefront of political and social conversation.

With a decision pending in Floyd v. New York City, a high profile federal case challenging these practices, along with relentless community activism and a hotly contested mayoral campaign, now is the time to push for leadership that acknowledges the crisis in policing and proposes criminal justice policies and social reforms that will actually keep our young people safe without criminalizing them.

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

In a recent mayoral debate, Bill Thompson, the only candidate to address this issue from the perspective of parenting a black son, said “I’m the one who has to worry about my son getting shot on the streets of New York … And at the same point, I don't have to sacrifice his constitutional rights to make sure he is safe … I can have them both."

As a parent, I worry about my son’s safety. As a lawyer, I worry about his rights. Stop-and-frisk promotes neither.

In this climate of heated discussion, the mayoral candidates must acknowledge that stop-and-frisk has proven so damaging and polarizing a practice that it has become New York City’s civil rights issue of the day. Those vying for New York City’s top office must articulate proposals for credible alternatives to stop-and-frisk policing that go beyond weak promises to train police in cultural sensitivity and professionalism.

New York’s next mayor can learn from the successes of other cities that have developed anti-gang initiatives, gun control programs and community collaborations.

Ironically, proponents of stop-and-frisk often cite parental desire for increased youth safety as one of the most compelling reasons for continuing this policy. Like all mothers and fathers, parents of young men of color want their children safe from drugs, violence, and many of the other harmful influences of New York City’s streets.

Yet, draping stop-and-frisk in emotional appeals to safety overshadows its damaging reality. Moreover, those arguments overlook evidence showing that the decline in serious crime in New York City cannot be directly attributed to stop-and-frisk.

While violent crimes fell 29 percent in New York City from 2001 to 2010, other large cities that do not rely on an aggressive stop-and-frisk policy — such as Los Angeles, Baltimore and New Orleans — experienced larger declines in violent crime. In terms of illegal gun recovery, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union, from 2003 to 2012, the NYPD increased stops by 372,060, but recovered only 96 more guns, amounting to an additional recovery rate of 0.02 percent.

In fact, in 2011, the NYPD recovered illegal guns four times more often through methods not involving street stops.

Young black and Latino men are indisputably the targets of stop-and-frisk. Male youth of color between the ages of 14 and 24 comprise less than 5 percent of this city’s population, yet they accounted for 41 percent of stops in 2012.

Appallingly, more than 90 percent of black and Latino youth stopped by the police were innocent of any wrongdoing.

These unwarranted stops are not without consequence.

Most critiques of stop-and-frisk focus on damaged police-community relationships and the fraying of youths’ willingness to assist police investigations. While these are significant costs, parents should also consider the emerging evidence of the emotional and psychological harm caused by these often disrespectful, humiliating, and threatening interactions.

Nicholas Peart, a young black man named as one of the plaintiffs in the Floyd suit, gave a first person account of the toll of being stopped and frisked: “Essentially, I incorporated into my daily life the sense that I might find myself up against a wall or on the ground with an officer’s gun at my head. For a black man in his 20s like me, it’s just a fact of life in New York.”

There are many facts of life that I am prepared to teach my young son. This should not be one of them.

Nicole Smith Futrell is a clinical law professor in the Criminal Defense Clinic of Main Street Legal Services at the City University of New York School of Law.