The ‘Wartime Budget’ New York City Needs

Mayor de Blasio is facing difficult budget choices (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Mayor de Blasio called the Executive Budget he presented on April 16 a “wartime budget.” With New York City’s economy shut down virtually overnight and without a clear path or timeline to reopening, that is definitely what the circumstances require. But, we don’t quite have one yet.

Estimates of cumulative city revenue losses from the city’s budget office and outside fiscal monitors range from $7 billion to $15 billion for this and next fiscal year, but there is no precedent for the current situation so modeling on the experience of past recessions could well understate both the extent and the timeframe of the losses. Absent a large infusion of federal assistance, the best way to close the city’s budget gap is more and larger expense reductions, not tax increases or borrowing.

While the Executive Budget, which will form the basis for negotiations with the City Council, shows an overall year-to-year reduction of 3.6 percent from the budget adopted last year, it would increase city-funded expenses by 1.3% -- not as generous as the annual growth in recent years (which averaged 4.8% for most of de Blasio’s tenure) but not a cut. Significant withdrawals from reserves and the Retiree Health Benefit Trust as well as $2.7 billion in cost savings currently make up for the anticipated loss of tax revenue. But most of these are one-time savings (and many caused by the impact of the virus and stay at home order); if tax revenue losses are higher and last longer because the economy doesn’t bounce back quickly, these actions will not be sufficient.

Moreover, there is little indication that the City Council is on a “wartime” footing and will refrain from its usual demands for more spending. In its formal response to the mayor’s Preliminary Budget, issued after the virus shutdown began, the Council listed many areas it believes should be fully funded and proposed adding more than $1.4 billion in new spending but suggested only half as much in spending reductions to offset it (and some of those savings ideas have been incorporated into the Executive Budget to offset current expenditures). And new legislation proposed by the Council last week, characterized as a coronavirus aid package, would impose new costs on businesses that would make it even more difficult and costly for them to operate and hence, to pay their employees and taxes.

The mayor is holding back on more cost-cutting in the hopes that the federal government will come through with financial assistance to help close city and state budget gaps. But the most recent aid package passed by Congress didn’t include state and local aid and Senate Majority Leader McConnell and other Republican legislators say they are not in favor of this type of assistance. Indeed, McConnell effectively said ‘Let ’em go bankrupt.’

Federal budget relief for states and localities is clearly warranted and some will eventually come through, but it will be preceded by a fraught, ideological battle about blue states’ high taxes and overspending and cannot be counted on to happen in time for final New York City budget adoption (on or before June 30). And New York State, which is facing its own $13 billion revenue loss, is not going to come to the city’s rescue. Indeed, aid reductions and cost-shifting by the state could make the city’s problem worse. So there needs to be a more serious plan to ensure that the city can balance its budget with little or no federal help.

It is difficult to cut city programs and services. Each one has a constituency of supporters who believe fervently in its importance. Many of the cuts and reductions in the Executive Budget, though relatively small and temporary, have already been decried by those who especially care about them, e.g. advocates of recycling urge restoration of the costly organics collection program; social service youth care providers denounce the suspension of the summer employment program. One of us is especially pained by the cut to a nationally recognized college completion program she helped create, CUNY ASAP.

But the city simply does not and will not have the money to keep doing everything in an annual budget that has grown to well over $90 billion. There will have to be deeper cuts and sacrifices of favored programs and activities than the Executive Budget proposes, at least for now. Labor contracts should be re-evaluated in light of the pandemic and efforts to achieve more productivity negotiated with public employee unions. Otherwise, the city risks having to take more draconian measures, such as laying off public employees and imposing cuts to essential services as the coming year unfolds.

Two things that should not be done except as a last resort are raising taxes and/or borrowing to pay operating expenses. It should be evident to the mayor and the Council that raising taxes now would only exacerbate the risks to the already fragile revenue base, as many business owners consider closing and the pandemic is causing many people to consider leaving New York.

Nor is borrowing a good idea. Borrowing money to fund capital projects is appropriate because the value of the expenditures for things like roads, school buildings, and water mains – their ‘useful life’ – lasts for years and it makes sense to pay for them over a long time period. In contrast, paying for current expenses like employee salaries pushes the responsibility for payment into the future, burdening taxpayers for years with debt service for services that have already been consumed.

Every $1 billion in borrowing now will cost at least $65 million a year for debt service every year the loan is outstanding (based on 5% interest on a 30-year loan). Especially now, every penny of the money that would go to interest is needed to pay for the costs of operating city agencies.

There will undoubtedly be many, including Council members and public employee unions, who endorse the borrow now, pay later approach because it avoids making hard decisions in the short run and allows city services and agencies to keep operating as if there is no problem. But if the economy and its tax revenue do not bounce back, the gap between costs and income will remain and more borrowing will be needed to close it.

This is a particularly frightening prospect to those, like one of us who was a First Deputy Budget Director in the mid-seventies, who remember the massive retrenchment and downsizing of city government during the fiscal crisis of that time. Instead of aligning the cost of city services with its revenue, it had borrowed money to pay its operating expenses year after year, until eventually institutions would not loan any more money because they realized the city would never be able to pay it back. There was literally not enough cash on hand to make payroll. (See this story for a good summary, with warning signs for today, of the fiscal crisis of the 1970s.)

Many felt it was acceptable when Mayor Bloomberg borrowed $2.1 billion to pay operating expenses right after September 11, 2001. But the nature of that crisis was quite different than what we face now. Only lower Manhattan was directly impacted and the rest of the economy, though suffering temporary setbacks, was able to quickly recover, so the city’s coffers could be replenished. In addition, Mayor Bloomberg instituted significant cost controls, including personnel reductions. The Council also agreed to an 18% increase in property taxes, and the state Legislature extended a 14% surcharge on the city personal income tax, neither of which would make sense in the current situation.

If, instead of making tough decisions about curbing expenses now, the mayor and Council decide to try and kick the can down the road by borrowing, the state Legislature should deny permission unless and until the city can demonstrate that it is holding the amount borrowed to an absolute minimum by taking every other possible step – including savings on personnel costs – to reduce the city-funded operating budget. If borrowing is permitted, it should be conditioned on the creation of a ‘control period’ during which the city’s finances are subject to oversight and intervention by the Financial Control Board, created during the ‘70s fiscal crisis to help ensure that the city adopted balanced budgets and sound financial management. Since 1986 the Board has served in a monitoring role, but this could be the time to bring it back into action.

Correction (May 7): In the original version of this piece, we incorrectly stated that after 9/11 Mayor Bloomberg negotiated a multi-year no-raise contract with the teachers’ union. That contract was negotiated during the recession in 2008, and mention of it has been removed. Mayor Bloomberg signed a 30-month contract with raises following the city-wide pattern of 4% a year with the teachers in early 2002 when he was pursuing Mayoral control of the school system. But, as we said, the city budget adopted post 9/11 did include significant cost cutting, including early retirement measures, attrition, and difficult and unpopular agency spending reductions such as curtailing plastic and glass recycling.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018. Norman Steisel was a First Deputy Mayor of New York City, Sanitation Commissioner, and First Deputy Budget Director, all between 1974 and 1994.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Cuomo's Density Dodge: Pandemics Aren’t Anti-City, Failure to Act Early Is

An altered image from one of Gov. Cuomo's briefings (by Aaron Carr, the author)

Dear fellow urbanites, city dwellers, and city lovers,

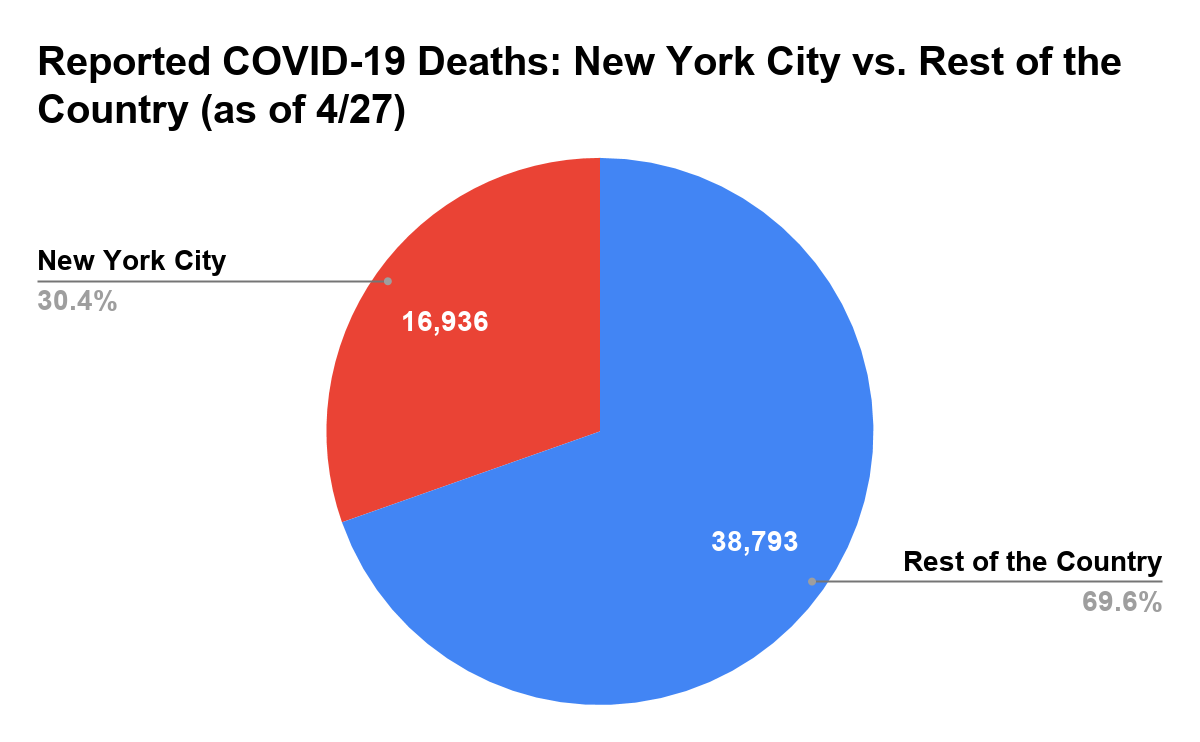

I regret to inform you that the heart and soul of New York City is under attack. And not just by COVID-19, which, as of April 27, has taken the lives of an astonishing 16,936 New York City residents, but by fictional statements made by our own governor, Andrew Cuomo, who has deceptively blamed the spread of this infectious, vicious, and deadly disease primarily on our city's population density.

The governor deserves commendation for often being a voice of reason in this crisis, but he deserves condemnation for failing to acknowledge his own mistakes and for attempting to distract from them by scapegoating.

Before a national audience of millions, the governor accuses our city’s density of being “dangerous” and “destructive.” But he’s wrong. Density is not dangerous and destructive –– a failure to plan, a failure to prepare, and a failure to act early is what has allowed COVID-19 to wreak devastation on New York. (Unfortunately, Mayor de Blasio has also relied heavily on this argument)

It is certainly fair to ask, “Isn’t density a factor?” And of course density is a factor, it’s just not the factor, and in no, way, shape, or form the most important factor.

California, for example, has many densely populated cities, yet responded much quicker than New York to the novel coronavirus. Governor Gavin Newsom’s stay-at-home order (the first in the country) was implemented on March 19 when California had just 1,006 confirmed cases. Governor Cuomo, on the other hand, delayed implementing such a decision until March 22 when New York had a whopping 15,168 confirmed cases.

Just consider for a moment the millions of New Yorkers who likely came in contact with each other during those few days — going to work, walking on crowded sidewalks, riding a packed subway car, rubbing shoulders, coughing, touching common surfaces, and all the while transmitting this highly infectious and contagious disease.

In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and former commissioner of the city’s Health Department, said “if the state and city had adopted widespread social-distancing measures a week or two earlier, including closing schools, stores and restaurants, then the estimated death toll from the outbreak might have been reduced by 50-80 percent.”

So, it should come as no surprise that, despite accounting for just 2.5% –– one-fortieth –– of America’s population, New York City represents nearly one-third of America’s COVID-19 fatalities.

Yet, instead of taking responsibility for his slow response, Governor Cuomo has launched a scapegoat campaign, blaming New York City’s natural identity -- our density -- as the source of the problem.

But the data, while correlational, strongly suggests that the governor is wrong:

If density is so destructive, there should be a strong positive correlation between the density of the five boroughs and number of COVID-19 fatalities and cases -- particularly in Manhattan, which is not just the densest part of New York City, but of America.

There isn’t.

If density is so destructive, New York City should not have 770 times the fatalities of San Francisco -- the second-densest large city in the United States -- despite having only 10 times the population.

But we do.

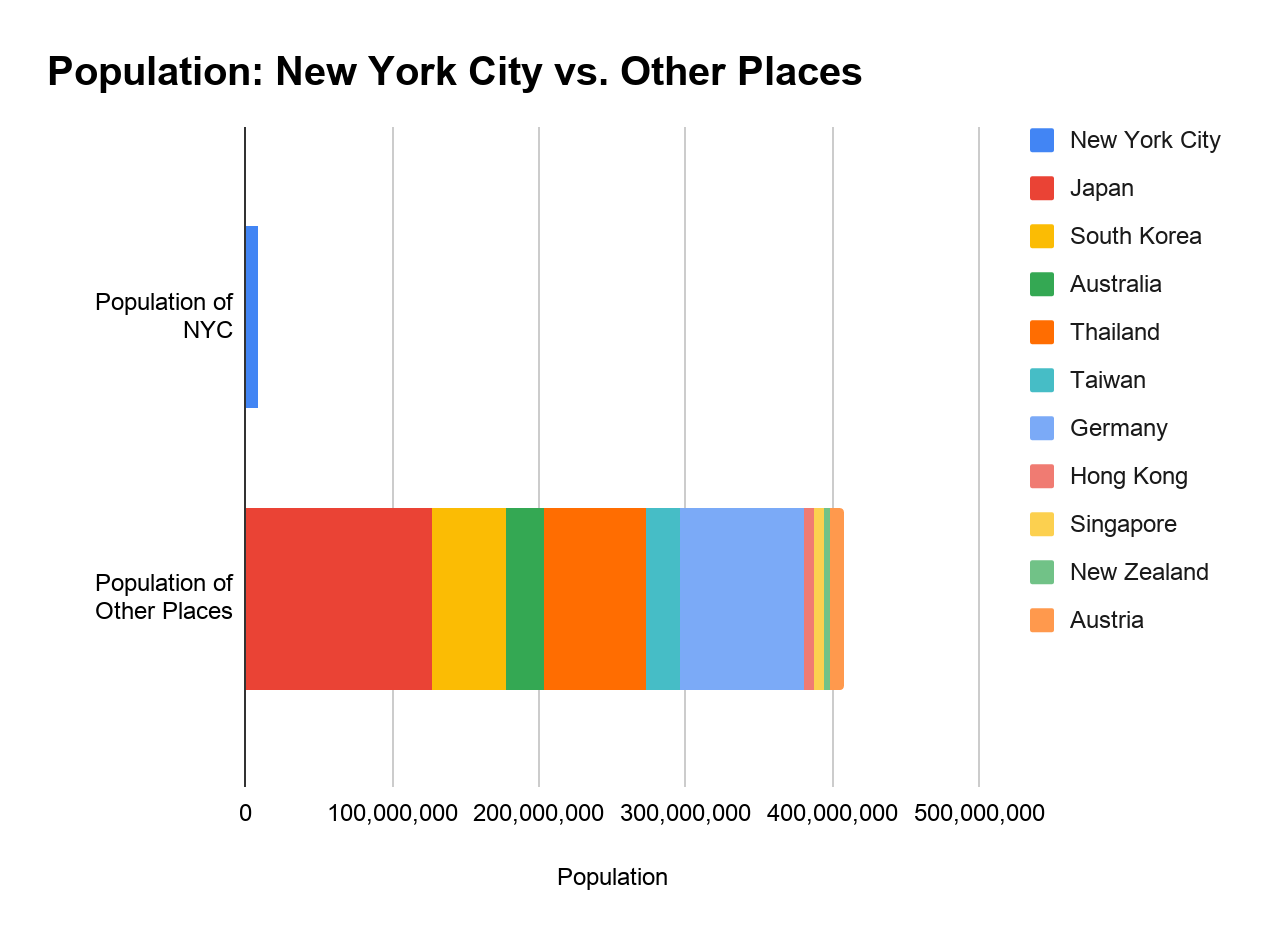

If density is so destructive, New York City should not have 1,210 times the fatalities of Singapore and 8,468 times the fatalities of Seoul (846,700% more), which is in close proximity to China, has a million more people, and is twice as dense as New York City.

But it does.

If density is so destructive, a single senior center in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, wouldn’t have had more deaths than entire cities and countries. But it has.

If density is so destructive, why does New York City have 9,621 more deaths than Japan, South Korea, Australia, Thailand, Taiwan, Germany, Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand, and Austria combined, while all these countries are home to dense cities and a total population of 400 million people.

Here’s the rub: Cuomo’s attack on density actually has little to do with density and everything to do with politics. Cuomo is a master politician, and like any master politician, he is a master of words. And, Cuomo -- always choreographed and calculated -- chooses his words with precision. In this case, by intentionally conflating the word “density” with “crowding,” which are two very different things. Density refers to the number of people per square mile of land. Crowding is when a large group of people convene together in a small space.

In a pandemic, it’s crowding -- not density -- that’s destiny.

Take for instance, the Smithfield Foods pork plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. More cases have been linked to this one plant than all of Seoul, South Korea, a city with 9.7 million people, in a country that at one point had the second most COVID-19 cases in the world.

The problem at the Smithfield Plant wasn’t density, it was crowding. And the same rule applies to cities in general.

San Francisco, for example, did not become a model for the country by reducing density, but by reducing crowding -- through aggressive, decisive, early action.

The reason Cuomo is putting his eggs in the density basket is because, unlike crowding, he can’t control density and therefore he can’t be blamed for the outcome. But knowing that he could control crowding early, and didn’t, the question then becomes, “why did Cuomo delay?,” and that is the last question Cuomo wants to answer.

To be sure, the majority of the blame falls on the incompetence, ineptitude, and callousness of the Trump administration, for, among other things, ignoring multiple warnings from his intelligence agencies and failing to provide states like ours with the support so desperately needed. History will not be kind to the president.

But in our decentralized system, it is governors that have jurisdiction over stay-at-home orders and the power to enforce them. Furthermore, the scientific literature demonstrates that early social distancing can be crucial in combating infectious disease.

There is no doubt that Governor Cuomo deserves praise for the exceptional job he has done keeping the public at ease and our city, state, and nation informed. But if we are going to learn lessons from COVID-19 and be better prepared for the future, we need an honest assessment of what went wrong. One that leads to a simple question of why 16,936 people have died in New York City, when only 22 have died in San Francisco, 4 in Hong Kong, and 2 in Seoul, South Korea.

The answer is not density -- it’s planning, preparation, and early action.

***

Aaron Carr is Founder and Executive Director of Housing Rights Initiative. On Twitter @aaronAcarr.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Addressing New York City’s Public Hygiene Crisis is a Coronavirus Recovery Must

Pizza Rat (Youtube); Dilapidated NYC Parks Bathroom, NYC Comptroller’s Office

The tens of millions annual tourists who supercharged New York City’s economic growth during the past few decades looked past the low public hygiene standards in their pursuit of skyline views and Broadway shows. Public restrooms? Very few and mostly awful. Overcrowded sidewalks? We got ‘em! Millions of long-suffering visitors and residents have had to tolerate oozing garbage bags on city sidewalks, grimy subway stations, crowded playgrounds, gross bathrooms in city parks, and more. When a pizza-eating rat in your city becomes a YouTube star (over 11 million views), you might have a problem.

New York City’s grittiness should become part of its storied history. There are many reasons why the city has become the world leader in the COVID-19 outbreak (overcrowded apartments, two international airports, social inequality, and more), but it didn’t help that the city’s public hygiene standards were so low. In order to bring back the tens of millions of tourists, and retain the residents and businesses, the city needs to rethink government and private-sector neglect of basic hygiene. The subways are in some ways now cleaner than they have been in decades, thanks to dedicated frontline staff, but city (and state) leadership needs to adapt the rest of New York to make it easier to stay clean and healthy.

Luckily, there are a number of relatively low-cost, high-impact approaches (what planners today call Tactical Urbanism) that could be implemented right away to reassure residents and visitors that the city and state take these issues seriously.

I am sure that many politicians will claim that they can’t spend the money on anything but the basics, but the city’s industries will not rebound until leaders can reassure visitors and residents that they won’t get sick. Funds should even be diverted from the state budget to make the city cleaner. New York City remains the golden goose for both state and city budgets. If we lose out to lower-density areas like Texas, it is lights-out upstate and down.

Public Restroom Revolution: A New Standard of Cleanliness

The city has flirted with additional public restrooms for decades, such as fully automated systems during the Bloomberg years, but the city hasn’t added a large number of public restrooms since Robert Moses built about 650 playgrounds, most with comfort stations, in the 1930s and 1940s.

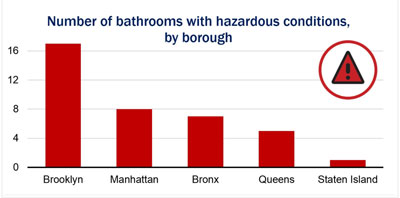

According to the New York City Comptroller’s Office, “New York City ranks a lowly 93rd in [public] bathrooms per 100,000 residents among the 100 largest American cities.” The public restrooms that do exist, most of them in city parks, are often dilapidated and unsanitary. The lack of numerous, spacious, and clean public restrooms has long been a threat to public health in New York; today, their absence could undermine the city’s recovery as a tourist destination and desirable place to live.

(The hazards in city park bathrooms include broken or damaged sinks, toilets, walls, and more (NYC Comptroller’s Office))

Adding public bathrooms in the short-term will cost money, particularly in labor to maintain them to a high standard, but adding restrooms now doesn’t have to be Second-Avenue-Subway expensive. A portable handwashing station costs about $800. Experienced companies like Callahead will gladly rent full restroom trailers, with private stalls, for city use. New York State, which should contribute to this effort, can paint them blue and add the state seal to make the experience more official.

(US Navy Handwashing Station (left); PolyJohn Portable Handwashing Station (right), $818)

(US Navy Handwashing Station (left); PolyJohn Portable Handwashing Station (right), $818)

(The Brighton Beach Restroom Trailer by Callahead (Left); Calypso Restroom Trailer (right))

(The Brighton Beach Restroom Trailer by Callahead (Left); Calypso Restroom Trailer (right))

These temporary restrooms could be deployed medium-term in cordoned-off parking spaces alongside city streets. Hundreds of them spread throughout the city’s commercial and residential areas would be a game-changer. The city regularly turns over valuable parking spaces to movie trailers for days and weeks, why not public restrooms? These restroom trailers would be staffed and maintained to high standards by attendants recruited from the growing number of people now unemployed in the city.

This “tactical urban” approach, using a short-term, low-cost tactic to demonstrate a long-term planning strategy, could deliver what the city has always needed: nice places to go to the bathroom and wash hands. Once clean and widely available temporary bathrooms are demonstrated as superior to forcing people to “hold it” or sneak into or beg for bathrooms in restaurants or cafes, these facilities can be upgraded into permanent, attractive, public restroom facilities. Bathrooms and sinks shouldn’t be ‘customers only.’

We have some great models out there for the long-term, including the super-popular bathroom at Bryant Park. I have personally waited many times to use that supremely-maintained facility.

(Bryant Park Bathroom, NYC Parks)

(Bryant Park Bathroom, NYC Parks)

Bryant Park is so good in large part because it has such great bathroom attendants. Adding bathroom attendants in larger private bathrooms—restaurants, bars, shopping centers—would be a major upgrade, too. The city should require all private businesses with larger restrooms to provide active human attendants. Some private bathrooms are well-managed, but most are only cleaned and monitored occasionally. There is a big difference between someone standing by a sink with a towel for you and an occasional janitorial visit. We need people watching to make sure that everyone is washing their hands. Much of the world has public bathroom attendants, including Mexico, and the bathrooms they supervise tend to be cleaner.

Hire More Park Attendants and Add Structured Recreation

(Sarah D. Roosevelt Park, NYC Parks)

(Sarah D. Roosevelt Park, NYC Parks)

City and state leaders had to close down playgrounds to stem the spread of the virus. But in the long-term city kids, especially those in cramped apartments, need parks for their mental, physical, and emotional health. Keeping playgrounds closed, or shaming families who allow their kids to play on sidewalks or streets, is cruel. Using the police to enforce social distance in parks is not only a waste of valuable resources, but may lead to blowback from overpoliced communities.

The potential solution to safely reopening parks goes back to New York City’s rich history of playground development and recreation planning. Many decades ago city parks were better staffed than they are today, with attendants and recreation specialists who took a much stronger hand in supervising play and looking after the equipment. Budget cuts have reduced the human presence in most city parks; changing social standards also restrained their power over kids and families.

It is a good time to bring back active attendants who can 1) regulate the number of children and parents in parks 2) organize kids into safe recreation activities that integrate social distance 3) clean and wipe down the playgrounds constantly and 4) make sure the bathrooms are maintained to the highest standards. Some of the current staff are already doing this difficult work, but the New York City Parks Department will need many new staff members to meet higher standards.

Rethink NYCHA Open Space and Create Neighborhood Parks in Streets

I wrote a column last winter about the vast reservoir of open space on NYCHA grounds and the potential to create new city parks in these underutilized spaces. NYCHA developments are often up to 80 percent open space, including, in total citywide, hundreds of acres of lawns with established trees.

Start pulling down the fences and finding new uses, including seating, outdoor eating spots, work-out spaces, and more so that the city’s residents can spread out and so NYCHA residents can finally use these spaces. Revamp the tired playgrounds, add temporary restroom trailers, and put in attendants.

Longer-term amenities could also be created on underutilized sites as was done at Carver Houses in partnership with Mt. Sinai Medical Center. These NYCHA open spaces belong to the public and should be made more useful for both residents and visitors.

(New exercise equipment on a NYCHA development)

(New exercise equipment on a NYCHA development)

In traditional neighborhoods, smaller streets can be closed for children’s play. The city’s Play Streets program needs to be supercharged. Local parks will both reduce the population pressure on city parks and keep the virus local if kids get it. The key is to furnish the closed streets in an affordable and usable manner.

All across suburbia, for instance, parents have taken over neighborhood streets during the crisis with portable basketball hoops for their kids. These cheap additions would work just as well on city streets that have been closed for kids. The hoops are cheap and many of them could be deployed on a closed street to reduce the number of kids playing. Paint could be used to create a court. Hopscotch, four-square, and other courts can also be painted. The classic fire hydrant can be partially opened to cool kids in the hot weather. Kids can bike around safely. Closing some cross streets won’t shut down the whole city either. Maintaining these spaces will also require attendants: more jobs!

(Portable Basketball Hoop, about $3,000 (left)/Painted Hopscotch (right, PxFuel))

(Portable Basketball Hoop, about $3,000 (left)/Painted Hopscotch (right, PxFuel))

Sidewalk Widening

There is a great deal of variation in sidewalk width in New York, but we know one fact for sure: few of them meet social distance standards. We need to make sure that smaller streets in neighborhoods like the Lower East Side get a minimum amount of sidewalk space for distance. Super-popular wide sidewalks, such as Fifth Avenue, need even more space for crowds. Thankfully, there is plenty of available space for sidewalk expansion: streets.

It is good to see the City Council stepping up for street closures, but in the long-term New York City will need to find practical ways to unclog the sidewalks while allowing for regular car and truck traffic. Many countries are already pointing the way by taking space from streets to make wider sidewalks and new bike paths.

Given the continued popularity of Citi Bike and need for more pedestrian space even pre-pandemic, shifting some space from streets to sidewalks and paths seems like a good option. This is a low-cost solution that will allow for the city’s business to continue. Once everyone realizes how nice it is to have wide sidewalks, and businesses start putting out more café tables, the sidewalks could be permanently widened.

(Federal Street in Auckland, NZ, converted during coronavirus (Ministry of Transport))

(Federal Street in Auckland, NZ, converted during coronavirus (Ministry of Transport))

This short article is not designed as an exhaustive list. The examples here illustrate that the city could implement modest improvements, at modest cost and enormous benefit, in the short-term.

They also test out temporary interventions with long-term potential. Their implementation would put a lot of people to work on beneficial projects in a time of mounting unemployment. Ordering people to wash their hands and cover their faces is crucial, but it will take a lot of creative thinking to make New York City a healthier place to live and visit.

***

Nicholas Dagen Bloom is a Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College. He is author most recently of How States Shaped Postwar America: State Government and Urban Power (Chicago, 2019). This essay draws inspiration from William H. Whyte’s classic film, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces and Mike Lydon’s books: Tactical Urbanism II and Tactical Urbanism.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

While Trump Debases Federal Inspector General System, New York City’s Remains a Model

NYPD IG Eure, second from left (photo: @OIGNYPD)

During our national coronavirus crisis, two Inspectors General stories were reported – one federal, one New York City – concerning how IGs exercised their statutory duty. No doubt the stories’ significance was lost because our attention is diverted. But they’re important, and telling.

On April 3, President Donald Trump gutted the Inspector General Act of 1978 when he proclaimed “You’re fired!” Michael Atkinson, Inspector General, Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Forty-two years ago, Congress passed the Act, which was supported by six Democratic and Republican presidents from 1978-2016, all recognizing the good government importance of independent oversight of the executive branch to ferret out mismanagement, abuse, and fraud of its programs and operations.

So why did Trump fire Atkinson – Trump’s own appointee – in essence ending independent federal IG investigations, especially after Atkinson supported Trump’s pre-inauguration plan to restructure “the bloated and politicized intelligence community”?

He dismissed him because Atkinson, doing his duty, investigated a September 2019 whistleblower complaint alleging that Trump pressured the Ukraine government to investigate Joe Biden and his son Hunter Biden, resulting in Trump’s impeachment and a Senate acquittal.

To Trump, Atkinson’s investigation was an unforgivable betrayal, as his appointee, no matter what the law required. Flailing to find a legitimate dismissal reason, Trump justified it claiming he "no longer" had confidence in Atkinson, whom he said did an absolutely terrible job -- but the pièce de résistance: Atkinson is not a big Trump fan.

We have heard this before, a Trump appointee promising the Senate to follow the law then forced out when Trump disagrees with his own appointee.

In November 2017, Atkinson at his Senate confirmation hearing swore, “[I]f I am confirmed...we [with Congress] will work together to encourage, operate, and enforce a program for authorized disclosures by whistleblowers within the Intelligence Community that validates moral courage without compromising national security and without retaliation.”

By a Senate voice vote, Atkinson was confirmed and by presidential directive went on his way to ‘fix’ the intelligence community.

After Atkinson honored his Senate promise, Trump retaliated, placing a black storm cloud over all federal IG investigations, ending independence, and sending an abusive message that IGs will be denigrated and dismissed when Trump disagrees with an investigation’s finding.

Atkinson was not the only IG to feel Trump’s wrath. On April 7, Trump publicly criticized the Health and Human Services deputy IG for a report concerning coronavirus-related shortages and testing delays at our nation’s hospitals. Trump used the refrain that the IG’s findings were politically motivated.

Apparently, no IG’s good government deed goes unpunished -- if the IG’s work gets in Trump’s way.

In contrast, in 1978 former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, by executive order and similar to the federal Inspector General Act, mandated all city government agencies have an IG. For 42 years – and five mayors – New York City has had effective oversight.

For instance, just on April 9, the NYPD’s Office of Inspector General – having a statutory function of oversight – issued its annual report. In a city where policing is always a contentious issue, the report raised serious concerns about racial bias in policing, compelling the mayor and the police commissioner to consider it and respond.

The report’s only issue, in my view, is the IG’s timing, releasing it during a pandemic when police officers’ health and safety are in jeopardy daily – almost 20% of NYPD personnel was out sick at one point recently. The IG report could have waited.

Timing aside, the NYPD IG met its statutory duty, apparently without interference or threats. Since the creation of the NYPD IG office in 2015, notwithstanding NYPD/IG disagreements, there have been 16 NYPD IG reports with recommendations for NYPD reform. Remarkably, and perhaps begrudgingly, the NYPD has accepted or implemented at least partially 76% of those recommendations.

Although a healthy tension exists between the IG and the NYPD, and between other IGs and their relevant agencies, the city’s IG system -- unlike the federal system under Trump -- has worked without a city IG hearing a Trumpian “You’re fired!” for doing an investigation or report.

However, on two occasions mayors have forced out ‘for cause’ the city’s chief IG — the Commissioner of the Department of Investigation.

In 1986, the mayor demanded the resignation of the DOI commissioner who was caught up in a criminal investigation of his staff member who installed an air conditioner in the commissioner’s home.

In 2018, the mayor dismissed his former campaign treasurer and appointee as DOI commissioner after an independent special investigator found the commissioner abused his authority and was “cavalier with the truth” during the investigation. The ousted commissioner claimed he was fired by the mayor because DOI had issued embarrassing administration reports.

Contrary to Atkinson’s dismissal, the DOI Commissioner — pursuant to the City Charter — was dismissed with due process and an opportunity to be heard.

Critically, an IG’s core principle is to independently investigate without being beholden to the appointing authority. This ensures good government when an IG makes recommendations and advises corrective action without the fear of reprisals.

Now, after Atkinson was dismissed without a rational basis, and to ensure all IGs are permitted to independently investigate, Congress must seek answers concerning Atkinson’s dismissal to determine if retaliation by a president for an IG doing his lawful duty are intolerable abuses of power.

To me, they certainly are.

***

Arnold N. Kriss is an attorney in private practice in Manhattan, and a former NYPD Deputy Commissioner for Trials and Brooklyn Assistant District Attorney. On Twitter @ArnieKriss.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Mayor's Recipe to Combat Hunger Missing Key Ingredient: Healthfulness

Mayor de Blasio holding a food package (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

New York City officials’ recently-released plan for how the city will keep New Yorkers fed during the COVID-19 public health and economic crisis does exactly that: tells us how New Yorkers will be fed. But where it missed the mark altogether is that it lacks any direction as to how it will keep New Yorkers well-fed.

The lack of consistent access to healthy food, which has been a looming issue in New York City, has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The de Blasio administration’s “Feeding New York” report outlines a plan to meet immediate needs and build long-term resilience in our food system. I stand by the administration when it comes to combating food insecurity and ensuring that New Yorkers do not go hungry in the midst of stay-at-home orders, job loss, and financial struggles.

However, the report, and more specifically the city’s food policy, neglects to adequately address nutrition and health when making food readily available to New Yorkers. Inattention to the nutritional content of food is concerning at a time when the public is at war with the health threats posed by COVID-19.

Those with serious underlying medical conditions, including multiple diet-related diseases, are at higher risk for illness from this novel coronavirus. Fortunately, wholesome, plant-based eating has the power to mitigate and sometimes even reverse ailments, such as Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and obesity. Less meat, dairy, and eggs. More fruits and vegetables. These diet changes would result in less fat and cholesterol and more fiber and essential phytonutrients. New Yorkers with diet-related conditions could significantly boost their immune function and bring their bodies into a state of greater overall health, which would thereby reduce the risk of complications.

Furthermore, the glaring racial disparities of COVID-19 can be at least partially traced to food injustices. As Mayor Bill de Blasio acknowledged: In New York City, the virus has disproportionately affected people of color. What does it mean when we see that while those who are Latino account for 29 percent of the population, they also account for 34 percent of total COVID-related fatalities? And how can it be that those who are categorized as black account for 22 percent of the population, but 28 percent of total fatalities?

These numbers tell a grim story. Grim, but unsurprising, as communities of color, populated by those who are identify as African-American, Caribbean-American, Latino, Asian, and American Indian/Alaska natives face the results of diet-related health disparities — unsurprising, given their poor nutrition profiles, which are high in fat and sodium, and low in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

That the New York City Department of Education (DOE) spent $16.9 million on milk and yogurt, compared to a mere $6.3 million on fresh fruits and vegetables in 2019 is emblematic of the city’s inadequate procurement of healthy foods. New York City prides itself on being a city that advances public health and sustainability. It’s unconscionable that the same city is spending almost three times what it is spending on fruits and vegetables on the unhealthy dairy products shown to be detrimental to people of color.

Agencies, food banks, and other institutions must shift their procurement practices to be increasingly plant-forward. Broader city expenditures on meat, dairy, and eggs versus fruits, vegetables, and grains should also be made transparent.

It is imperative that we prioritize feeding our communities foods that can boost their immune systems and reduce their risks for susceptibility to chronic disease. In addition to social distancing and the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), a nutritious diet can play a significant role in preventing more deaths. Feeding our communities cannot only be a logistical, tunnel-visioned conversation of quantity; it must also be one of quality.

***

Eric Adams is the Brooklyn Borough President. On Twitter @BPEricAdams.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Coronavirus Crisis Reinforces the Climate Emergency, Our City Budget Must Recognize That

City Council Member Antonio Reynoso, the author (photo: Emil Cohen/City Council)

These months will go down as one of the most trying periods in our city’s history. We are consumed by the grief of lost loved ones, colleagues, and neighbors, while facing a level of economic uncertainty not seen in generations. In this moment of crisis, many of us feel compelled to put on blinders and focus solely on addressing the present situation, and there is no doubt that efforts to combat COVID-19 will require vast resources and attention from our best minds.

As with many other issues confronting our communities, the impacts of COVID-19 are exacerbated by a broad array of societal problems, particularly environmental degradation and injustice. We must take a comprehensive approach to fighting this disease, one that not only looks to meet our short-term needs, but puts forth solutions that greatly improve our public health and economic resilience to prevent and withstand future emergencies. This starts with protecting our environment.

Research is now showing that communities most impacted by pollution, predominantly black and brown communities, have higher rates of infection and death from COVID-19. This should come as no surprise. The virus impacts the respiratory system; high levels of pollution lead to increases in respiratory illnesses, which leave the body less equipped to fight off the virus. With this knowledge in hand, one would expect our leaders to double down on environmental initiatives to improve our air quality.

However, following the pattern of past economic downturns, environmental programs are among the first to see budget cuts, allowing elected officials to crow about a balanced budget, while their constituents are left vulnerable to future catastrophe.

In June of last year, the New York City Council officially declared that we are in a climate emergency. COVID-19 has not displaced this emergency, which worsens by the day. And yet, the proposed cuts in the Mayor’s recently-released Executive Budget directly target concrete initiatives that would mitigate effects of climate change: suspending the city’s organics program, which will lead to increased methane emissions, and disinvesting from building bike lanes, making it harder for people to use alternative modes of transportation at a moment when people are more hesitant than they’ve ever been to ride public transit. Environmental initiatives, like a robust organics program and network of bike lanes, are not just necessary components of a well-functioning, modern municipality, they are also basic elements in any plan to mitigate an environmental catastrophe and improve public wellness.

The scope and scale of both the public health and economic costs of climate change have the potential to dwarf what we’ve witnessed during the immense coronavirus crisis. Future generations would be left to deal with rising sea levels, longer and more frequent heat waves and droughts, and poor air quality. The results will be tragic; millions living in low-lying areas will be displaced from their homes, food and water shortages will occur, and deaths from heat and respiratory-related illnesses will skyrocket.

Responding to the twin emergencies of COVID-19 and climate change can seem overwhelming, but it presents a critical opportunity to improve our public health, revive our economy, and create greater equity within our communities. This is precisely the time to make investments that better prepare us for the next emergency. But before we can make further environmental investments, we must stop divesting in the limited number of environmental initiatives already on the books. We must protect and accelerate progress already underway.

As we watch the coronavirus curve flatten, we should not be thinking about how we “get back to normal” – normal is what left us unprepared, normal is what led to people of color dying from the virus at greater rates, normal is what left low-income folks completely devastated by the economic downturn.

We must rebuild our communities with equity and resiliency top of mind. This is not the time to follow the Republican orthodoxy of austerity; this is a time to figure out how we can prevent future large scale crises, like the looming climate crisis. Our goal should be a green economy, allowing us to reduce pollutants -- improving public health and mitigating climate change -- all while putting people to work building solar panels, processing compost, growing food locally, and in myriad other vocations.

We can start by preserving the environmental initiatives we already have. If we do not rise to tomorrow’s climate crisis with the necessary urgency, the coming decades will bring cascading crises that no government will be equipped to respond to.

***

City Council Member Antonio Reynoso represents parts of Brooklyn and Queens. On Twitter @CMReynoso34.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The State Legislature Claims To Be Co-Equal, So Why Is It Letting The Governor Block Popular Solitary Confinement Restrictions

Gov. Cuomo at a correctional facility (photo: governor's office)

On April 3, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo rammed through a budget that will be devastating to New Yorkers and then on April 4 declared that the legislative session was “effectively over” for the year. Several legislators immediately pushed back.

Comments from legislators on social media ranged from “Hell no” to “King Cuomo seems confused” to “Oh cool. So now there’s just one branch of government?” Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie immediately issued a statement in response, emphasizing the Assembly as a “co-equal branch of government” and stating that the session is not over and that they established a system of remote voting. Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins had previously stated that they “intend to continue to do our work,” that they had set up a system to do so remotely, and that the Senate and Assembly are “co-equal branches” with the Governor.

While there are many ways that the Legislature can, and must, exert its authority as in fact a co-equal branch of government and show that New York has a functioning democracy with an independent legislature, there may be none as obvious or urgent as passing the HALT Solitary Confinement Act, (S.1623/A.2500), which has majority support in both houses. Among other provisions, HALT would end all forms of solitary confinement beyond 15 days, in line with international standards on torture, and create more humane and effective alternatives.

Every day that the Legislature fails to enact HALT means thousands of people - overwhelmingly black and Latino people - suffering, deteriorating, and too often dying in solitary confinement. Every year that goes by without legislators having an opportunity to vote on the bill means tens of thousands of New Yorkers being locked in six-by-nine cages and tombs.

This practice of inhumane torture has gone on far too long. Solitary causes such deterioration and intense suffering that self-mutilation is a regular known outcome. Solitary is associated with increased rates of heart disease, psychosis, and death -- while people are in solitary and when they return home to the outside community. I am a solitary confinement survivor and the collateral damage from my time in solitary still affects me today.

While the United Nations has deemed any length of time in solitary as torture in some circumstances and solitary beyond 15 days as torture in any circumstances, New York regularly holds people in solitary for months and years, and sometimes for decades. In the words of some New York legislators themselves, “That is wrong. It is cruel. It is inhumane. It must stop.” “I can think of no practice more inhumane than solitary confinement.” “It has no business in the state of New York.” “What should have happened already, we are demanding a vote.” “I wanna vote for that damn bill now.”

HALT currently has 34 Senate co-sponsors (a majority is 32) and 79 Assembly co-sponsors (a majority is 76), and many additional legislators in both houses have committed to vote for the bill. A wide range of legislators -- from Long Island to Syracuse to New York City -- have been vociferously and relentlessly calling for HALT to be brought to a vote. There is not another bill in the Legislature that has this number of co-sponsors and this level of support.

Despite this widespread support and more than enough votes for passage, the bill has not yet been brought to a vote. In 2019, Governor Cuomo pushed the legislative leaders to not bring HALT to a vote and so they did not. In 2020, with all of the outcries of “pass HALT now” from legislators and community members across the state, now is the moment.

In a functioning democracy, with independent and co-equal branches of government, when a majority of legislators are ready to vote for a piece of legislation that piece of legislation must be brought to a vote, passed, and put on the Governor’s desk. It is long past time for a vote on HALT. Leadership must resume the legislative session remotely and bring HALT to a vote immediately.

***

Victor Pate is a survivor of solitary confinement and the Lead Statewide Organizer for the #HALTsolitary Campaign. On Twitter @mrvictorpate & @NYCAIC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

On #EarthDay50, The Answer to Two Existential Crises is Staring Us in the Face

The future is renewable, the author writes (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

On this 50th anniversary of Earth Day—Wednesday, April 22, 2020—, the world is in crisis. An unbearable number of lives lost each day. Livelihoods disappearing or threatened. And the uncertainty of what might come next is disrupting communities. Our infrastructure is strained to the brink and our most marginalized communities are bearing a disproportionate brunt of the pain. I’m of course talking about the ongoing devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The tragedy is that these disruptions are already equally true of our ongoing climate crisis. The impacts of climate change can be seen in the swarms of locusts ravaging East Africa, the wildfires that have raged across California and Australia, the heatwaves shattering records across the globe. And it came for New Yorkers when Hurricane Sandy roared ashore in 2012, the worst natural disaster New York City has faced. These climate disruptions will only be made worse and more chaotic in the reality of our new COVID-19 world. In many ways, this global health emergency has given us an early preview of how our climate crisis will unfold.

Yet it doesn’t have to be that way. At this moment when we are debating our path forward from this pandemic, we have a clear choice. We can simply choose to get “back to normal” — but we know that the status quo was not working. Or we can choose to emerge stronger and more resilient from this crisis with a green recovery that prioritizes clean energy infrastructure, job creation, and environmental justice: a Green New Deal for all Americans.

The recovery in front of us is perhaps the last, best opportunity to choose a new future and avert the even worse impacts that climate change will cause going forward.

The immediate health crisis has of course not yet abated. But we cannot lose sight of the climate crisis and the threats to public health and well-being that it poses, with the worst still looming ahead. We face a climate emergency primarily caused by the continued burning of fossil fuels and the decades-long campaign of deception and denial by the fossil fuel industry.

Here in New York City, we remain committed to ending the age of fossil fuels and investing in clean energy climate solutions as part of our world-leading Green New Deal climate policy.

That’s why Mayor de Blasio signed the world’s strongest municipal ban on fossil fuels as part of the second wave of New York City’s Green New Deal, making opposition to projects like the Williams pipeline our default position going forward. It’s why we are divesting our pension funds from fossil fuels, which are dragging down our economy. And it’s why we enacted ambitious building retrofit mandates to halt our carbon pollution at its source.

Of course, it’s not enough to just say no to fossil fuels. We need to say yes to job-creating investments in clean energy like solar, wind, and hydropower.

And in this moment, we need federal support to make that happen. With Congress continuing to grapple with the right way to recover from this pandemic and spur the economy, the obvious answer is staring right at us and we must have the courage to seize it.

Investing in clean energy and resilient infrastructure over the next decade would spur our nation’s economy, and create enormous numbers of good-paying and accessible jobs, at just the right moment to align with the scientific demands of our climate crisis and the needs of an American economy that is suffering its worst unemployment since the Great Depression. So let’s put Americans back to work putting solar power on every roof, building out the extensive offshore wind necessary to power our cities, installing the long-distance energy transmission that can connect clean energy to our local communities, and building out the resilient infrastructure that will protect us from the next disaster.

This Green New Deal would put millions of Americans back to work, get our nation on track to solve our climate crisis, clean up our air and water, and address the inequities that ravage our marginalized communities.

And over time this strategy will pay for itself in cleaner air and better health outcomes, avoided damages from severe storms, and a renewed economy that leads the world in renewable energy and clean industry that also rights the environmental injustices of the past at the same time.

We’ve emerged stronger after tragedy before – whether 9/11, Hurricane Sandy, or the Great Recession. Our current challenges are no less potent, but the opportunity right now is pivotal. We must put solving the climate crisis at the heart of our recovery from this pandemic – at the scale and pace of our climate emergency – because our unsustainable practices have pushed our planet to the brink.

This may be our last chance. The moment to choose a better future—a Green New Deal—is now.

***

Daniel A. Zarrilli is New York City’s Chief Climate Policy Advisor. On Twitter @dzarrilli.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Persistent Themes and New Projects as Earth Day Hits 50 in New York

Key themes of the first Earth Day remain on the 50th (photo: governor's office)

A half-century ago, the United States celebrated the first Earth Day. In New York City, Fifth Avenue connected Union Square Park and Central Park with tens of thousands of New Yorkers celebrating the environment and urging their government to take swift and decisive action to protect their air and water. Today, 50 years later, the world has been put on pause to combat a health crisis unseen in generations. But while we are unable to again take to the streets to mark Earth Day, it does not mean that the same spirit—or the same environmental issues—have vanished.

During the 1950s and ‘60s, New York City suffered from horrible toxic smog that killed hundreds a year and sickened many more. Thankfully, we don’t face the same scale of air pollution today, but it doesn’t mean pollution is any less deadly. In fact, we are seeing first-hand that our vulnerable and disadvantaged communities who carry the burden of poor air quality are also seeing the highest death rates of COVID-19. A recent report from Harvard connected these dots: death rates from COVID-19 infection are higher in areas of poor air quality.

In spite of this, the Trump Administration has consistently and aggressively moved to protect and prop up polluters. It has ignored science, rolled back regulations, and tried to return the country to a time before there was an Earth Day.

So, if we can’t rely on the federal government, then it is again up to New York State to take the lead on protecting our air, water, and climate. We are in a good position to do so, having taken a huge step forward last year when state leaders passed a law that fights climate change by moving the entire economy of New York off of polluting fossil fuels and onto clean, renewable energy. That means electrifying all vehicles, expanding mass transit, transforming buildings, and developing the workforce necessary to get the job done. But that transition will require dedicated funding to help lift up the communities hit hardest by this crisis, and it’s the polluters who should be picking up the tab.

We must also expand and strengthen other pollution-reduction programs already on the books. For example, New York (and several other states in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative) make polluting power plants pay for the carbon they dump into our skies. That money—$1.3 billion since the beginning of the program—is then put into efforts that cut energy bills. This has been a successful program but could be more so by closing loopholes that exclude some of the worst polluting power plants and dedicating at least 35 percent of clean energy funding to frontline communities who suffer the worst from pollution.

Finally, we need to focus on programs and projects that will assist in an economic recovery and help protect our public health. Today, you will no doubt use tap water multiple times to wash your hands and protect yourself against the spread of COVID-19. Clean water and hygiene are at the front line of our defenses during this public health crisis, underscoring the need to continue to make investments in the state’s aging drinking water and wastewater infrastructure. There is a long line of shovel-ready projects throughout the state waiting for funding that will ensure clean water in our communities. Thankfully, this year’s state budget has authorized $500 million for these kinds of clean water projects. This will be an immediate environmental and economic catalyst for communities all over New York and why the state needs to move quickly to get these projects going.

New York faces an unprecedented and uncertain future thanks to COVID-19. And the difficulties we confronted before this crisis started haven’t disappeared. Climate change still threatens, and we still need to protect our air and water. But the one thing that this situation has proved is that New Yorkers can come together and do what needs to be done to protect the health and well-being of ourselves and the environment. Fifty years ago, it was taking to the streets. Today, it’s staying at home. Tomorrow, it will be the hard work of ensuring a healthier, more equitable and economically vibrant state.

***

Peter Iwanowicz, Executive Director of Environmental Advocates of New York, is one of the nation’s foremost climate advocates and a recent appointee to New York’s Climate Action Council. On Twitter @greenwatchdogNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Now More Than Ever: Abolish The City Marshal

The city should eliminate the marshal position, the author writes (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office:)

Since the 17th century, down on their luck New Yorkers have faced a familiar spectre: a New York City Marshal.

The marshals are enforcers of court judgments including evictions, foreclosures, utility shut-offs, and debt collections. The difference between the New York City Marshals and New York City Sheriffs are that sheriffs are salaried public servants employed by the city while the marshals are technically private entrepreneurs who, despite being appointed by the mayor, are contracted by landlords, banks, utility companies, debt collectors, etc.

For each job, the marshals collect fees and are also entitled to a 5% cut of the total amount collected, known as “poundage.” Not surprisingly, the marshals thrive in times of economic hardship; in 2009, at the nadir of the Great Recession, the marshals recorded their best year to date, with over a third of them having earned over a million dollars. This is why it’s important, now more than ever amid vast economic hardship and more ahead, to abolish the city marshal system and transfer its duties over to the New York City Sheriff’s Office.

You might be wondering: how is it that in 2020 the mayor of the proverbial “greatest city in the world” still appoints what are essentially legally-authorized bounty hunters? Mayor de Blasio, to his credit, has spoken out against the marshal system. But so too have several mayors before him. The reason why the marshals have been able to remain as an immovable part of the city’s firmament is a long history of patronage, influence peddling, and political inertia.

The marshal system was first established in 1655 when New York was then a Dutch colony and has been in operation ever since. Opposition to the marshal system goes back to the early 20th century, with the formation of good government groups that rose against the venalities of Tammany Hall-style influence and corruption. Pressed by groups like Citizens Union, mayors as far back as Fiorello La Guardia sought to abolish the marshal system, and almost every mayor since John Lindsay has come into office nominally against it. (Bloomberg was the exception; he liked the idea of privatized enforcement and appointed 20 new marshals.)

Each ran into the same problem: the New York City marshals are protected under New York State law. The most concerted effort to abolish the marshal system in the state Legislature, which Jack Newfield and Paul DuBrul described in vivid detail in their terrific book “The Abuse of Power,” was in 1975. Organized by Citizens Union, the bill had passed in the State Senate, but failed in the Assembly. The Speaker at the time, Stanley Steingut, ruled over Brooklyn’s Democratic Party, in which patronage plums like recommendations for marshal appointments were a mainstay, and so Steingut smothered the bill by sending it through the Assembly committee of a fellow machine loyalist where it failed to reach the floor for a vote.

Ever since, the marshals have maintained their license to scavenge at the expense of the city’s most indigent by reinvesting no small portion of their earnings into political influence. They are prolific campaign contributors, which is why, despite a succession of mayors who came into office against the marshal system, each not only stood down from their opposition, but also consented to an expansion of the marshals’ powers. Mayors Dinkins and Giuliani, both having received significant contributions from the marshals, ultimately supported legislation that allowed the marshals to collect judgments awarded by the state Supreme Court (in addition to civil court). Today, the marshals’ lobbyist and spokesperson was de Blasio’s biggest bundler in his first campaign for mayor. (De Blasio, apropos of a Bloomberg News series that described the essential role the marshals had played in enforcing a type of predatory lending scheme called “merchant cash advance,” did say in December 2018 that the continuing existence of the marshal system “needs a new look” and questioned whether the system “makes sense at this point,” but nothing ever came of it.)

In 2020, the marshal system simply does not make sense – neither financially, according to the Independent Budget Office, nor as a tool of effective governance, as the backroom “clubhouse” dealmakers who protected the system have ceased to exist.

Indeed, the county party machines are hardly the potent force today as they were decades ago (or two years ago for that matter); while the State Senate Independent Democratic Conference, and especially former IDC leader Senator Jeff Klein – to whom individual marshals, as well as their PAC, had contributed tens of thousands of dollars – had been voted out by a new crop of legislators with a more promising vision of how government should work for people. In other words, the political resistance to this proposal no longer exists.

While the marshal system may still work well for the marshals’ clients: landlords, Con Edison, or debt collectors – who benefit from a privatized enforcement system that incentivizes fast turnover and imposes a merciless discipline on those who are going through a tough time – it does not work well for New Yorkers.

Any realistic anticipation of the economic fallout from COVID-19 that’s underway must take into account that until the federal government figures out how to develop an administrative infrastructure that can deliver stimulus directly into people’s pockets, it is incumbent on state and municipal governments to protect citizens from eviction or having their power turned off or their wages (or stimulus checks) garnished.

Yet, as The City has reported, already the New York City Department of Investigation (which oversees the marshals) has questioned the city’s authority under the current legal status quo to intercede against a marshal’s ability to collect on a debt. But by transferring the marshals’ duties over to the city sheriff’s office – that is, to public servants employed by the city – only those city employees would be authorized to enforce a collection. The same goes for other civil judgments. New York City’s government, in other words, would have a monopoly on enforcement. Instead of delegating this authority to for-profit contractors, the city would be accountable for those most in need.

The city must step up to this task. If the state will allow it.

***

Duncan Bryer was formerly the Director of Policy for Brooklyn State Senator Julia Salazar. He currently advises the senator and is a graduate student of economics at John Jay College, City University of New York.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Sirens and Suffering: Rethinking the Soundtrack of the Coronavirus Crisis

Sirens and the city (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

A beautiful, clear April evening in Manhattan. No traffic, which is down 84% overall in the city, says StreetLight. Out of nowhere a screeching siren pierces the air. Many minutes later an ambulance appears—SeniorCare—blaring a siren that measures 124 decibels, higher than a jet takeoff or a thunderclap, the loudest natural sound on earth. The few people on the street cover their ears in pain as the noise gets ever louder, remaining in the air for several more minutes even as the ambulance disappears from sight.

Why the deafening siren on an otherwise quiet night? The argument has always been that sirens are needed to move traffic out of the way in emergencies, so that responders—firefighters, police officers, medical technicians—can make their way as quickly as possible. But this argument fades as traffic disappears under the pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic that has shut down the city, forcing worried New Yorkers to shelter in place as the sirens heighten and prolong their anxiety. We’re living in a strange new world of danger and disease. The often-interminable sirens are becoming the defining sound of the pandemic in New York City, throughout all five boroughs, much as the distinctive European siren once defined World War II.

Ironically, even though noise complaints, including sirens, have for decades topped the quality-of-life list of complaints by residents to elected officials, no methodologically sound, controlled study has ever been done on the underlying assumption that justifies extraordinarily loud sirens in New York: Do sirens effectively expedite emergency vehicles? And do ever louder sirens carrying ever greater distances expedite vehicles faster and more efficiently? In other words, do sirens make us safer? The few studies that have been done show that very little time is saved by emergency sirens, as concludes a major literature analysis for the federal Emergency Medical Services.

Anxiety in Anxious Times

A recent review of medical research articles for the British journal Lancet on the psychological impact of disease outbreaks determined that quarantine can trigger depression, irritability, insomnia, post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger. For people quarantined and on edge, sirens can become intolerable. After all, high-pitched, ear-splitting emergency sirens are intended to generate fear and anxiety in nearby human beings—and they succeed. For most people, noise levels over 70 decibels provoke physiological changes, constricting blood flow to the extremities while increasing it to the brain.

Yet sirens operate way above 70 decibels, meaning they have traumatic effects on people almost by definition. The specifications for sirens on New York City fire engines have long been set for 118 decibels at 50 feet. According to manufacturers, ambulance sirens range from 110 to 129 dB, which means that even at their lower end ambulance sirens are dangerously loud.

To put these decibels, which are measured on a logarithmic scale, in perspective: Quiet breathing registers 10 decibels; your refrigerator humming, about 40; quiet conversation, around 60; shouting across a room, 75. A sound of 40 decibels will awaken sensitive people; 70 will wake up almost anyone. Back when Midtown traffic was heavy it ranged from 80 to 95 decibels, while an express subway train roaring through a local station, such as 86th Street on the West Side, regularly hits 110. Noise of 120 decibels causes discomfort and sometimes injury.

Emergency Responders

But it’s not only the citizenry endangered by excessive sirens—it’s also the emergency responders themselves.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health warns that two years of regular exposure to 90 decibels will produce hearing loss. For decades agency heads—and siren manufacturers—discounted any damage to emergency personnel, arguing that sirens were directed away from them. But common sense says that if people standing on the street—or 40 floors up in a high-rise building—can hear the ear-shattering sirens, then so can personnel in the vehicle.

In 2017, some 1,500 current and retired firefighters from New York joined 3,000 first responders from Chicago, Boston, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey in a mass lawsuit against siren manufacturer Federal Signal Corp, arguing that the sirens left them with serious hearing damage. After losing a jury trial in Chicago, the company successfully argued in federal court that the sirens needed to be heard from all directions. The court did not address the question of hearing loss. Roughly 26% of firefighters nationally report suffering regularly from tinnitus (ringing in the ears).

Richard E. Fairfax, Director of OSHA’s Directorate of Compliance Programs, noted that in addition to hearing loss, with “consistent exposure to 95 decibels occurs, there exists a serious threat to the cardiovascular system, more specifically an elevation in systolic blood pressure (hypertension), digestive, respiratory, allergenic and musculo-skeletal disorders, as well as disorientation and reduction of eye focus, potentially leading to the increase of accidents and injuries.”

Protocols

Official New York State policy calls for the siren to be sounded when lights are on but this varies widely in practice by agency and by employer. On a sunny Saturday morning last month an MTA bus pulled over on Amsterdam Avenue. Lights flashing but with no sirens, four NYPD patrol cars answered a distress call from a bus driver who said he was being assaulted by a passenger.

Meanwhile, a siren blared far away. Quite a bit later a Mt. Sinai ambulance appeared, driving very slowly up a traffic-free Amsterdam, lights flashing and sirens screeching at a decibel level of over 120, high enough to temporarily deafen most people.

Said one of the police officers: We try to restrict our sirens as much as possible. Our drivers are sensible and take proper care, but we know how much sirens disturb people. Said an ambulance driver: Mt. Sinai protocols call for us to use full sirens and lights. It’s to protect you as much as to protect us.

But why, in a time of extraordinarily high levels of anxiety for many New Yorkers, especially as they’re confined to their homes, and with streets often nearly empty, should the protocols for high-decibel sirens remain unchanged? Mt. Sinai ambulances (as well as those from once-independent hospitals like Lenox Hill) seem always to be running with full sirens, no matter how slowly they’re proceeding. The slowness just worsens the pain of those assaulted by the noise.

Aware of intense hostility to the sirens on its 25 ambulances, Mt. Sinai experimented last year with different options, including the high-low, European-style siren. After playing the sirens at community board meetings to solicit public opinion, Emergency Medical Services Director Joseph Davis concluded, "People hated them all, but the 'high-low' was least intrusive. It didn't have that piercing sound." A 40-year EMS veteran who himself suffers hearing damage from the job, Davis fully understands the consequences of sirens.

The presumption that every ambulance is on a life-saving mission is far from true. Year-to-date FDNY data show an overall 73 percent increase in 911 calls that resulted in “refusals of medical aid,” or RMAs, meaning that the person refused to be taken to a hospital after the ambulance arrived. In the first half of April the number of refusals surged 235%.

Part of the problem is that dispatchers do not solicit sufficiently precise information. Last month four black cars and an ambulance drove the wrong way on our empty street, sirens blaring. They parked haphazardly, and left the lights flashing. The four drivers pushed by the doormen, heading in different directions and getting lost. The emergency call turned out to have been utterly erroneous—a housekeeper unable to access her employer’s apartment had contacted a neighbor, who called for an ambulance. The employer, who had been on the phone, refused to open the door for the housekeeper—or the EMTs. Surely the dispatcher should have obtained more information about the nature of the “emergency,” which was non-existent.

Overall 911 call volume is way up—202,000 calls year-to-date compared with 167,000 for the same period last year. How many are true emergencies? A rigorous study would be helpful.

Quiet Streets

As the coronavirus has raged in New York it has cleared many streets of car and truck traffic, inducing unusual quiet that is broken by little except sirens. Ironically, manufacturers deliberately calibrate sirens to be heard above traffic under the assumption that the most important factor is moving cars out of the way. Pedestrians have seldom been considered, even as pedestrians have become increasingly important to urban life. And as New York streets have emptied out in the last several weeks, the sirens have continued to blare for previous levels of ambient noise, making them far louder in practice since there is little or no environmental noise cushioning the sound.

Excessive sirens are a direct consequence of excessive traffic. If the traffic is curbed, as so many New Yorkers urge, then the sirens can be modified as well. This is the moment.

Urban designer and architect John Massengale proposed a radical innovation on Streetsblog: A network of what he calls quiet streets, many of which would be car-free or nearly car-free, for example: “In the long run, Broadway north of Columbus Circle could be a pleasant street with light traffic on both sides, while Columbus Avenue or West End Avenue might be the best streets for little or no traffic. These are just quick ideas. A broad study of traffic on the Manhattan grid might have different and better long-term solutions for breaking the car culture.”

Not only would quiet streets be productive for neighborhoods, they would offer a route to rethinking deployment of emergency vehicles, which would be able to move more freely—albeit carefully—while employing far less aggressive sirens. Without traffic registering 80 decibels and above, sirens would have no justification for their now excessive levels of 120 decibels.

The Future

All of this needs to be rethought in the coming months.

In his masterpiece, Plagues and Peoples, historian William McNeill makes a crucial point for our time: All historic plagues have had a second and sometimes third or fourth wave of contagion after the first. When this wave of COVID-19 hospitalizations slows, New York needs to prepare for the next wave—and that means seriously analyzing and probably rethinking its delivery of emergency medical services.

Manhattan City Council Members Carlina Rivera and Helen Rosenthal have already started, introducing a bill to require the gradual introduction of high-low sirens, and to mandate a maximum sound level not to exceed 90 decibels, which would constitute an enormous change.

***

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a writer and planner. On Twitter @JuliaManhattan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.