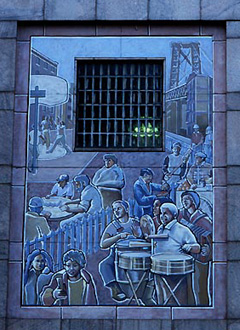

Richard Haas White St. Detention Center |

Several years after Richard Haas painted an epic mural about a century of immigration to the Lower East Side, the artist was confronted by a group called the Down With The Mural Committee. They objected to one of the seven panels, which depicted a modern-day vendor at the center of some familiar if unflattering street life -- a bodega with its steel gate down, a sleeping vagrant, some stray dogs, a woman in a halter-top. These images, painted in 1989, were insulting to the community, the protesters said.

Haas, a well-established artist who has received commissions throughout the city and the country, was taken aback. Nevertheless, he agreed to replace his work with a completely new scene – no more woman in a halter top; now there are two children on their way to school. Gone are the bodega, the dogs and the vagrant; now there are basketball players, a baseball player, construction workers, even a Tito Puente-like band.

“I was surprised by the protest," Haas was quoted as saying in 1992. "But working in the public arena today is like stepping into a mine field."

The story of Haas’ mural is told briefly in “City Art,” which is both a current exhibition at the Center for Architecture and a newly published book about New York City’s Percent For Art program. His is far from the most controversial commission in the 22-year-old history of the program, though it may be among the unluckiest.

Elizabeth Turk Manhole Cover Seguine Avenue, Staten Island Launch slideshow for more images |

The law that created the Percent for Art program in 1983 (some 25 years after the first such program began in Philadelphia) requires that one percent (more or less) of the budget for every city-funded construction project be used for public artworks. Since then, more than $26 million has been spent on some 200 works of art in locations throughout the five boroughs. Because the last two decades have seen a boom in school construction, the art is mostly in schools. But some of it is in courthouses, firehouses, and libraries, and a few pieces are in far less traditional venues: Sculptor Elizabeth Turk designed 87 manhole covers for Seguine Avenue on Staten Island; Milo Mottola created a life-size, totally operable “Totally Kid Carousel” atop the sewage treatment plant in Harlem

Haas’ mural is on the wall of a jail. This would be bad enough, but the jail is the notorious Tombs, now in its third building and officially known as the White Street Detention Center. (The person who launched the protest was a newly transferred deputy warden, who was an official of the Department of Correction Officers Hispanic Society.) Even worse, the complex in which the prison is located is named after Bernard Kerik.

But what may be worst of all is that, most of the year, the mural is virtually invisible, completely obscured by the leaves of the trees that line White Street – and too high up for eye-level viewing in any case.

This is not mentioned in the book or the exhibition, or on the Web site of the Department of Cultural Affairs, which administers the Percent for Art program. Just walk down to White Street near Baxter, and see (or, actually, don't see) for yourself.

The mural’s literal obscurity, and the controversy in its past, prompt a few questions: What is public art, and who (and what) is it for? Is public art for the public? And who, exactly, make up the public? Does public art have to be educational? Must it reflect the values of a democratic society and those of the community in which it is located, or can it challenge those values? Can it depict a community's reality -- the way things are, no matter how unfortunate -- or must it reflect a community's aspirations -- the way things could be? Or should it simply insert a bit of pleasure into the busy lives of passers-by?

These are precisely the questions that the contributors to “City Art” pose. (The last question is from the book’s essay by art critic Eleanor Heartney.) The exhibition, as its introductory wall text puts it, "invites viewers to consider the role public art plays in our daily lives and communities, and in shaping our identity as New Yorkers.”

Alice Aycock Project for the 107th Police Precinct, Queens, 1992. Community members were at first alarmed. |

It is easy to overlook this daily role, since for most people, art becomes public only when there is hoopla -- such as the two-week spectacle of The Gates Project in Central Park -- or when there is heat: The controversies connected to public art pale beside the ruckus kicked up over “indecent art”, but Percent for Art projects have had their share:

- Education officials requested the alteration of some of the porcelain figures of students that Ann Agree had created for the lobby of Intermediate School 137 in Queens, removing “doo rags,” tank tops, religious ornaments and jewelry; they also asked her to include a figure in a wheelchair. As the exhibition explains, “Agee complied with some of the requests and eliminated certain figures that she wasn’t willing to alter.”

- Community residents were baffled by the structure Alice Aycock created for the top of the 107th precinct in Queens. It resembles a satellite dish and, to the artist, was a symbol of the communication that police must have with the community. Some residents thought it was an actual dish however, and either suspected it was being used for surveillance or feared it would interfere with their television reception. Despite such worries, the sculpture remains in place.

- Residents of the South Bronx objected to the art commissioned for another police precinct, the 44th, which John Ahearn had based on life models made of actual if not thoroughly upstanding people from the neighborhood, one shirtless posed with a beat box, another in a hooded sweatshirt with his pit bull. The sculptor agreed to take the works down; they are now exhibited in Socrates Sculpture Park.

This last controversy was the subject of “Whose Art Is It?” by Jane Kramer, a celebrated 1993 piece in the New Yorker magazine that was turned into a book much talked about in the art world.

Such disagreements are sure to continue. This is why community feedback is built into the process; the local community boards are involved from the beginning. In the same neighborhood where Ahearn’s sculptures were commissioned, a work in progress by Cai Guo-Qiang outside the new criminal courthouse inspired community objection because it looked like a huge granite chain -- reminiscent, some said, of a chain gang, and thus inappropriate for the courthouse. The artist changed his sculpture, as community board 4 district manager Margarita Hunt-Tejada explains, to look more like “interlocking cubes instead of chain links.” Clearly, it takes a certain kind of artist to participate in public projects – one who is as comfortable with politics as with paint.

But the new public art -- not just from the Percent for Art program, but from the Arts for Transit program in the subway as well -- could never be mistaken for the public art of the past, those rusted-green military generals. True, some of the art is still meant to inspire awe in heroes, though the heroes have changed: A new mural by Daniel Galvez entitled “Homage to Malcolm X”, which includes a reprint of the “Whatever Means Necessary” speech, will be one of the three Percent for Art works incorporated into the newly renovated Audubon Ballroom, reopening this month.

Launch slideshow for more images |

But all those whimsical and intriguing mosaics in the subway stations, all the imagination that pokes out from the corner of your eye throughout the city (see slideshow) -- the pieces created over the past two decades surely do what Picasso once said art can do: “Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life,” an impressive feat in a place as full of dirt as New York.