It is the best of times; it is the worst of times. New York has always been a city of both wealth and poverty, but never more so than now. It’s easy to spot the wealth – getting a clear view of the poverty is a bit more complicated.

A recent WealthInsight study sets the number of millionaires in Manhattan at 389,100, defining millionaire as someone with net assets over $1 million excluding their primary residence. America's second city for millionaires is Los Angeles, with a mere 126,000. More breathtaking, Manhattan boast 70 billionaires — more than any other city in the world (Moscow is second with 64; L.A. has just 19). Why not in a city led by the world's wealthiest mayor, reportedly worth $27 billion?

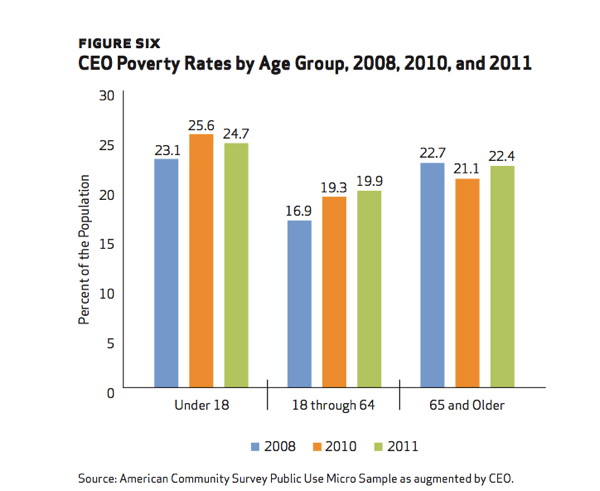

The Center for Economic Opportunity, a city project initiated by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, recently issued its "Poverty Measures Annual Report" for the city with statistics through 2011. It's an interesting read because the CEO uses a poverty measure different than the official federal poverty rate.

The official rate produces a national poverty level without regional adjustment. The CEO measure adjusts for variations in area housing costs and it's based on National Academy of Science criteria reflecting what families actually spend on necessities, but also includes the value of noncash benefits like SNAP payments (food stamps), free or reduced rate school meals, Home Energy Assistance, housing assistance and so on, as income.

The official 2011 federal poverty rate in New York City was 19.3 percent , though it's now 21 percent . The 2011 CEO figure was 21.3 percent , a full 2 points higher. It was worse for hard-hit subcategories like non-citizens (28.9 percent ), kids under 18(24.7 percent ), single parent homes (30.9 percent ) and the Bronx (26 percent ). The poverty rate for kids in single parent homes was 34.7 percent . Asians CEO poverty rate was 26.5 percent and the rate for Hispanics was 25.3 percent .

Now in the throes of sequestration and a public policy of austerity, assistance resources for poor people have generally gone from few to really meager. There is Temporary Aid for Needy Families, but only for families with children and limited to an aggregate five years over a person's lifetime with the requirement that family adults work for the benefit. New York has a Safety Net Assistance program for those who have exhausted their lifetime federal benefits, but that generally has a two year limit for regular cash benefits.

New York City's safety net for homeless families in shelters used to include a priority for public housing or Section 8 vouchers, but that generally stopped after 2004, replaced by a transitional rent subsidy program which was also eliminated in April of 2012. Now the only generally available program for moving most homeless families to permanent housing is a job. That's if you can find one and if it pays a living wage.

New York's Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness estimates unemployment among homeless families at 57 percent. In fact, ICPH's 2011 survey of homeless parents found 68.5 percent unemployed.

Sequestration has foreclosed on some of New York City's tools. It visited Section 8 housing cuts on the three agencies issuing vouchers in New York City, meaning 5,000 planned housing vouchers won't be issued. New York City's Housing Preservation and Development Department lost $36 million and plans to cut 1,000 vouchers. "The real problem is," HPD Commissioner Matthew Wambua says, "these are our neediest tenants, the ones who cannot even afford the units in our developments."

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

He notes 32 percent of HPD's vouchers go to elderly renters and 44 percent to disabled people. Still, to avoid eliminating even more vouchers Wambua plans to reduce subsidies for many current Section 8 recipients, with reductions to subsidies as high as $400 a month.

New York City's Housing Authority and the state Department of Homes and Community Renewal both issue Section 8 vouchers in the city and have suffered sequestration cuts. They too won't issue a large number of planned vouchers.

The recently passed city budget does add some NYCHA resources, but not enough to overcome the public housing repair backlog, and certainly not resources to make up for sequestration cuts.

Even having a job isn't necessarily a get-out-of homelessness free card.

Most homeless people who find employment work in low wage jobs in fast food, child care and personal services, security work or retail sales. Fast food and security jobs often start near minimum wage. Even work in the healthcare-childcare and personal services fields pay an annual median income of $22,980 for homeless heads of household in New York City, according to the ICPH survey.

The federal poverty level for a family of four is $22,811, though the CEO sets New York City's poverty level at $30,945. Among the 22 percent of homeless families with a fulltime worker, most remain in poverty. Even among all New York families with two fulltime workers, 4.9 percent are in poverty.

A better way to understand poverty in New York City is to consider income inequality. Since 1967, the U.S. Census Bureau has used a measure, the Gini coefficient, sometimes referred to as the index of income correlation, as a measure of income inequality. It's a ratio of income dispersion comparing the median income of the highest quartile (20 percent ) to the lowest quartile median income. The higher the coefficient is, the greater the income inequality. If all families had the same income, the coefficient would be 0. If one family had all the income and the rest had none, it would be 1.0. In 1967, the first year the Census Bureau used it, the national Gini coefficient was .34. But in 1969, 1970 and again in 1974 it was as low as .326

The Census Bureau's 2011 national Gini coefficient was .477. But for Manhattan it was an extraordinary .601, the second highest number for any county in America. If Manhattan were a country, its Gini coefficient would be among the highest in the world — meaning the greatest income inequality — including most sub-Saharan nations, Middle Eastern emirates and third world countries. Manhattan's median income for the top 20 percent of earners was $391,022, compared to a $9,681 median for the lowest 20 percent. Top earners made better than 40 times what the bottom fifth did.

New York really is a tale of two cities: a rich gloriously city and a desperately poor one. The two cities cover the same geography but offer very different views. The ICPH study has a dire warning: "If changes are not made to the current system, family homelessness will only continue to grow" from its already historic highs.

All of the 21 percent living in poverty in America's richest city — nearly 1.75 million people — are at risk of homelessness if something isn't done about it.

Jeff Foreman is policy director at Care for the Homeless. Follow him on twitter @JeffForeman2.