Hammel Houses vs. New Affordable Housing; David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York

As time marches on, and NYCHA projects stay the same, the sense of public housing as an isolated, stigmatized part of the city has grown. When most NYCHA projects were created between the 1930s and 1960s, boxy red brick apartment houses were pretty typical for a wide range of the city's residents. Since the 1960s, however, the city's affordable and market housing developers and architects have better integrated their towers into existing neighborhoods and experimented with exterior treatments including stone veneers, glazed brick, multi-colored bricks, glass, tiles, metal accents, and much more. Today's affordable housing buildings, in neighborhoods like Melrose in the Bronx, are often as attractive, and often more carefully designed, than unsubsidized apartment buildings.

NYCHA, by contrast, has preserved and renovated its red brick towers, mostly because to do anything else has been prohibitively expensive. In addition, because most NYCHA towers are fifty years or older, NYCHA's capital division is forced to go through a lengthy and expensive historical review process for basic renovation projects even when there is no architectural distinction at all to the towers undergoing renovation. Residents seem equally reluctant to embrace any changes, despite the longstanding sense among many residents that their apartments may be a good deal, but building exteriors are unattractive and isolating.

If we have learned something over the decades it is that curb appeal matters, especially when it comes to affordable and public housing. If NYCHA is going to attract and retain working families in the long term, some updates are long overdue. How housing looks also plays a role in how much pride people feel in their surroundings and how they treat those environments. The institutional appearance of NYCHA arguably discourages pride of place among many residents and visitors alike.

Appearance also has an even more important "other directed" quality that influences the politics and funding of housing. How the city's population as a whole feels about NYCHA is crucial as federal sources of funding, which have provided nearly all of NYCHA's subsidies for eight decades, dry up. Few non-NYCHA residents are eager to foot the bill to preserve the basic brick public housing towers in their neighborhoods, some of which also have serious social and crime issues that detract from neighborhood safety. If NYCHA projects, however, fit in better or enlivened surrounding neighborhoods, city residents as a whole might be more eager to subsidize the system out of their local taxes.

In New York, nationally, and around the globe there are many efforts underway to alter the visuals of subsidized housing. Some of these strategies are worth considering or adapting for NYCHA. The creative approaches featured here share in a tradition of adapting existing towers without displacement of current residents. Many of these adaptations would be expensive, far beyond NYCHA's current budget capacity. The De Blasio administration, rather than NYCHA, could sponsor and pay for a few demonstration renovation projects of NYCHA projects out of the city's capital budget (or the "preservation" budget of the Housing NYC plan) that could point the way to a new look.

New "Skins" for Old Buildings

There are many good reasons to pursue a policy of "re-skinning" or recladding NYCHA buildings with panels of various materials. NYCHA's red brick towers are minimally attractive and expensive to repoint. New "skins" available today, overlaid on top the brick, could provide extra insulation and additional protection from elements. New mechanical systems could also be run beneath or through the new exterior panels thus improving water, heat, electrical, and even internet service to residents. In the Rockaways, for instance, private developers made good use of reskinning to rebrand and redevelop a decayed subsidized project that had been poorly managed by its former owners. This approach could be adapted for NYCHA buildings as well.

(L and M Recladding in the Rockaways)

NYCHA, as part of the planning for Sandy Recovery projects, asked some of its participating architects to include with their basic repair plans more ambitious visions. The results are impressive and indicate the adaptability of the current NYCHA inventory—if costs were not such a limiting factor. The images make clear that new surfaces covering these places could work better for residents (in terms of mechanical systems and insulation) as well as make developments more inviting parts of neighborhoods.

(Red Hook Houses Recladding Proposal, NYCHA Capital Projects Division + KPF, ARUP)

Finding "Lost" Details

Cosmetic changes, at more moderate costs, could deliver some powerful visual results that might be welcomed by both residents and neighbors alike. The Dearborn Homes on Chicago's South Side, for instance, have been renovated and given appealing Georgian details. These alterations would be particularly welcome in residential areas of Queens and the Bronx where NYCHA towers often form a strong contrast to surrounding homes and apartment buildings.

(Dearborn Houses in Chicago Before and After, HPZS Architects)

Rediscovering Retail

The best of the early housing projects—First Houses, Williamsburg Houses, and Harlem River Houses—included stores and community facilities open and connected to their surroundings. Federal rules, and other factors, led to the elimination of most stores on NYCHA grounds from the 1940s to the 1960s, when most projects were built. The absence of vibrant street life and commercial, and the security stores provide for pedestrians, has been a major criticism of NYCHA design.

Today's NYCHA leaders, for a mix of financial and social reasons, are considering the redesign of ground floor spaces with new stores that could add liveliness and much needed revenue. The example of Stuyvesant Town could serve NYCHA well, where new ground floor retail has helped perk up public spaces for a middle-income complex. More stores and street life on and around NYCHA might go a long way to creating safer public spaces as well.

(Stuyvesant Town New Café at Ground Level; David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York)

(Stuyvesant Town New Café at Ground Level; David Schalliol, Affordable Housing in New York)

Signage and Balconies

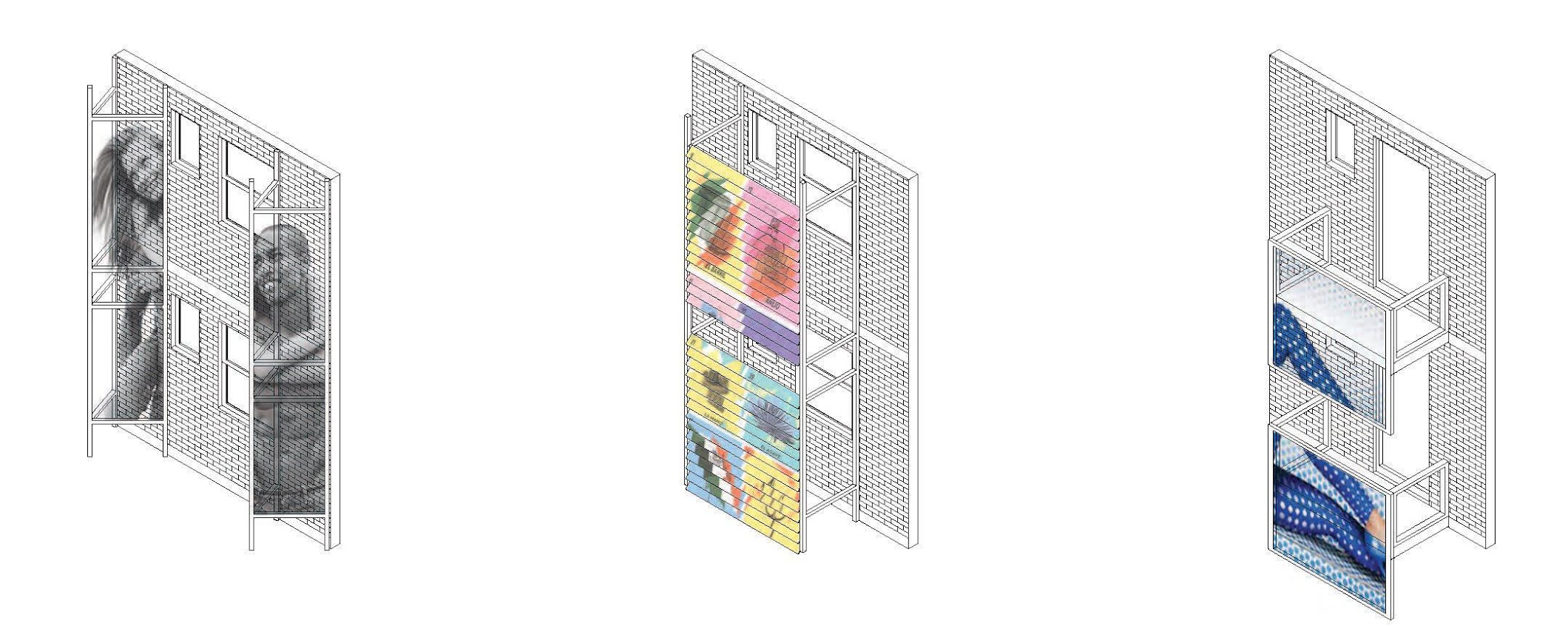

New exterior adaptations have the potential not only to brighten up drab exteriors but also contribute directly to NYCHA's financial bottom line. The creators of public housing in the 1930s disliked commercial signage in residential areas, but today's urban neighborhoods are often enlivened by signs of all types. Architect Matthias Altwicker proposes that new exterior signage, some with advertising, could enliven the building exteriors. Some might hang off existing walls, while other signs might be part of new balcony systems.

(Commercial Additions to Typical Red Brick Towers, Matthias Altwicker Architect)

(System of Simple Applied Structures to provide sun shading for all types of orientation, advertising surfaces, and adding balconies where floor plans permitted.)

Signage could also be applied to new structures rising on NYCHA grounds. FEMA is providing money for moving boilers and other mechanical systems above the flood zones. Most of the architects commissioned by NYCHA to create hurricane resistant buildings have simply matched the red brick boxes to their surroundings. Altwicker proposes, instead, that the new brick buildings instead become lighted beacons in their neighborhoods. These could provide a sense of orientation for the areas, brighten dark areas at night, and potentially feature community news and events along with space for advertisements to generate revenue.

(Elevated Mechanical Buildings as new "Lightboxes" by Matthias Altwicker Architect)

The examples of design strategies for NYCHA are provided here to get the city and NYCHA residents thinking about ways of refreshing dated housing projects; this quick set of examples is not designed to be an exclusive list of options. Around the globe and in New York, however, designers and housing authorities are giving new life to aging public housing projects. New York should join in this tradition of renewal to make a more livable city—for both NYCHA residents and those in surrounding neighborhoods.

*This is part three of a three-part series on NYCHA from Nicholas D. Bloom and partners*

Read part one: Rebuilding NYCHA: A Fresh Look

Read part two: Goodbye to 'First Generation' NYCHA

***

Nicholas Dagen Bloom and Matthias Altwicker are Co-Curators of the current exhibition at the Hunter College, East Harlem Gallery, Affordable Housing in New York.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.