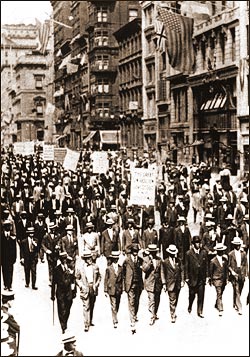

Protest march down Fifth Avenue, 1917.

|

Brian Knowlton joined tens of thousands of other New Yorkers on the East Side of Manhattan on February 25 to protest the U.S. preparation for war in Iraq. And like many others that day, he was arrested -- in his case for not moving when a police officer asked him to.

Rather than simply being given a ticket, Knowlton was held at One Police Plaza and questioned -- not just for his name and address but about his political affiliations and who had accompanied him to the rally. "The detective asked, 'So do you come to these things often?' - something like that," Knowlton recalled.

Confronted with evidence of such interrogations, the police department admitted last week that they had asked similar questions of many people arrested at protests beginning in mid February and had compiled the answers on special "demonstration debriefing forms." Under fire from civil liberties groups, who called the practice "chilling" and "intimidating," Commissioner Raymond Kelly said the department would end the practice.

The police department also has backtracked from its denial of a permit to march for the February 15th mass anti-war demonstration, granting such a permit to a later demonstration. But at the same time the department has not backed down from reviving a practice that was banned almost 20 years ago, the surveillance of political activity. And the federal government, which has already cracked down on the rights of non-citizens, is considering measures that would allow the government to take citizenship away from Americans who support groups the government considers terrorist.

New York, long a center of protest, has in the last several months been what one reporter called "the spiritual center of the anti-war movement." In a city edgy with fears of terrorism, New Yorkers marched, rallied, staged "die ins" and practiced civil disobedience. As activists mounted the first mass protests in New York since the terrorist attacks of September 11, they confronted heightened security concerns head on.

"A national conversation is starting about what kind of country we want to live in and what balance we will tolerate between public safety and private freedom," Matthew Brzezinski wrote in the New York Times magazine. Depending on whether there are further terrorists attacks, he continued, "we may come to think nothing of American citizens who act suspiciously being held without bail or denied legal representation for indeterminate periods or tried in courts where proceedings are under seal."

A HISTORY OF PROTEST, AND SUPPRESSION

The history of dissent in New York goes back a long way -- as have the efforts to suppress that dissent.

One reason for New York's prominent role is because it has long served as the center of U.S. publishing, and the many writers and editors of dissenting publications added to the range of voices heard in the city. New York also has always had the highest concentration of immigrants, who bring their varied viewpoints and, often, an antipathy toward authority learned in the old country. Jewish immigration in the late 19th and early 20th century, for example, spurred the development of an American socialism that was particularly strong in New York. Italian immigrants also played a major role in the early days of the labor movement in New York, demanding rights for workers.

"The matrix of ideas is richer here, and in part it's richer because it reflects debate and discussion overseas as well as at home," says Joshua Brown, director of the American Social History Project at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, who says that for much of its history New York has been "the exception to the rule" of the American mainstream.

But just as dissent has flourished here, so have efforts to suppress it, particularly when Americans feel threatened. "In time of war or national emergency, we respond too harshly in our restriction of civil liberties, and then, later, when it is too late, we regret our behavior," Geoffrey R. Stone, a professor of law at the University of Chicago has written.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln several times suspended the writ of habeas corpus which requires that a court show why someone is being charged. The nationwide crackdown had a disproportionate effect in New York where many people, particularly Irish immigrants, opposed the war. By the early 1860s, writes Kevin Baker, as many as 10 percent of New York City men were arrested, most for dodging the draft or otherwise resisting the war effort.

During World War I, President Woodrow Wilson warned that disloyalty "must be crushed out of existence." Opposition to the war was particularly strong in New York, where settlement house workers, groups championing women's rights, and many immigrants had been against U.S. involvement in the conflict. Some 2,000 people were arrested for opposing the war – including, for example, Mollie Steiner, a Russian Jewish émigré who had handed out anti-war leaflets in the city.

The suppression continued with the Red Scare of 1919 and 1920, when New York State's Lusk Committee tracked down and arrested communists, focusing on immigrants in New York City.

In the 1960's, with much of the country caught up in protest movements, New York did not stand out as much as it has in more politically sleepy times. But dissent thrived here as well, spreading beyond the anti-war movement to such protest movements as the demand for community control of local schools, and the gay rights movement, which got its start in Greenwich Village in 1969 when police raided a gay bar and patrons fought back. Campus protest, which began in Berkeley, moved east most famously in 1968, when students at Columbia University occupied some of the school's buildings to demand that Columbia not build a gym in Morningside Park, a protest to which the administration responded by calling in the police.

While much of the rest of the nation seemed to settle down for a while, protests continued in New York, from the giant 1982 demonstration in Central Park calling for a freeze on nuclear weapons to the acts of civil disobedience in front of police headquarters, after the killing of unarmed Amadou Diallo by undercover New York City police in February, 1999, to the local protests against the U.S. Navy's shelling of the Puerto Rican island of Vieques.

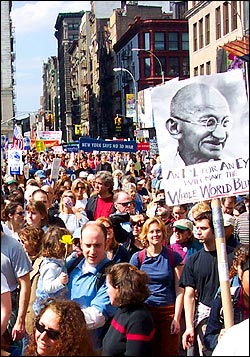

Protest march on 17th Street, 2003.

|

THE ANTI WAR MOVEMENT

The war in Iraq has highlighted once again how New York often stands apart. In much of the rest of the country, business and private citizens have been staging their own crackdown on those who oppose the war.

A security guard employed by a shopping center had an Albany lawyer arrested when he refused to take off a t-shirt reading "Peace on Earth." People at a Houston rodeo spat upon and assaulted a 16-year-old who refused to stand when a flag-waving song blared over the loudspeakers. A boycott resulted in reduced air play on radio stations for The Dixie Chicks after one of the group said she was ashamed that President George W. Bush is from Texas. Last week, the president of the Baseball Hall of Fame canceled the museum's 15th anniversary celebration of the movie "Bull Durham" because Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon (both New Yorkers), who starred in the film, vocally oppose the U.S. war in Iraq. Dale Petroskey, president of the hall, said the actors' comments "ultimately could put our troops in even more danger."

"'Rally 'round the flag,' is the resounding cry heard throughout the nation," said Maurice Carroll, director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute. But, he added, "In New York City, that cry is muted."

A Quinnipiac University poll taken soon after the U.S. attack began found 49 percent of New York City residents opposed to the war, contrasting with a national poll taken in which only 26 percent of Americans opposed the war.

An anti-war activist, Reverend Earl Kooperkamp of St. Mary's Episcopal Church in West Harlem, told a reporter, "This is an unprecedented mass movement and New York is setting the tone."

While supporters of the war, including officials in the Bush administration, see it as a response to the events of September 11th, and say it could help stop terrorist attacks on the United States, some New Yorkers say the exact opposite. The fact that they live in the city that experienced the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history has made them skeptical; they question how war will make them safer.

Activists have urged that the trade center attacks not be used as a justification to wage war. Shortly after the attacks, artists stood silently in Union Square bearing signs reading, "Our grief is not a cry for war." Not in Our Name has called upon the government not to use the September 11 attacks as a justification for roundups of Arabs and Muslims or restrictions on civil liberties.

"New York was the city that suffered the greatest losses in the September 11 attacks, and New Yorkers who are against the war feel a special moral urgency in standing against the wanton attacks on other cities," said Kimberly Dillon, a New Yorker active with the M27 Coalition, which advocates direct action against the war.

As it has for more than a century, the presence of so many immigrants in New York also helps shape the debate here. Andrew Beveridge, a sociology professor at Queens College, said immigrants get information from different sources than other Americans, such as the Arab cable network Al-Jazeera (whose footage is shown on various ethnic television stations), and so come away with a different perspective. The immigrants on his campus – wherever they are from -- "see the U.S. as a big bully."

THE POLICE RESPOND

"In any civilized society the most important task is achieving a proper balance between freedom and order," Chief Justice William Rehnquist has written. "In wartime, reason and history both suggest that this balance shifts in favor of order – in favor of the government's ability to deal with conditions that threaten the national well-being."

With the nation involved in a war on terror as well as a war in Iraq, law enforcement in New York has reacted warily to protests and activism.

Last September, before the anti war movement really got going, the Bloomberg administration asked a federal judge to remove most provisions of the 1985 agreement that limited police monitoring of political activity. The restrictions were instituted after activists filed a class action suit to stop undercover police from watching demonstration and meetings and compiling dossiers on participants.

But police now say the rules, called the Handschu agreement, make it hard to find terrorists before they launch an attack. "It is difficult to imagine a state of affairs more outdated by the events of September 11," police Intelligence Commissioner David Cohen said.

Judge Charles Haight, who had signed the original agreement, apparently concurred and lifted most of the restrictions on the condition that the police agree to guidelines for monitoring their own behavior.

The judge's move could mean a "return to the bad old days of police dossiers on law-abiding critics of government, infiltration and disruption of lawful political activity and organizations, and intimidation and punishment of dissent," Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union told the Village Voice.

The police department also cited security concerns when it denied United for Peace and Justice a permit for a February 15 march past the United Nations to protest the war. The courts upheld the decision.

Instead, the city let demonstrators hold a stationary rally on First Avenue. But that created its own problems. Police directed demonstrators to block-long pens, created with barricades. More than 250 people were arrested, many for trying to get to the rally. Rather than being released with warrants to appear in court at a later date, they were taken into police custody, denied access to lawyers, according to Risa Gerson of the National Lawyers Guild, and, as has now become evident, questioned about their political activities.

At another demonstration, on April 7, police arrested about 95 people, some of whom attempted to block entrances to the Carlyle Group, a private investment group.

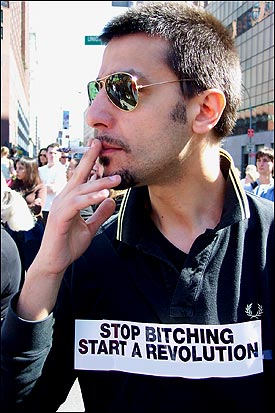

Near Union Square Park, 2003.

|

The demonstrators practicing civil disobedience expected to be arrested. But Beth Andrews, a spokesperson for the M27 Coalition, said she was across the street performing street theater when she was picked up. She and the others remained in custody for about 10 hours. According to Joel Kupferman of the National Lawyers Guild, police asked many of those arrested about their views on Israel, Palestinian rights and terrorism. This is, he said, "an attempt by the New York City Police Department to break the right of dissent."

Commissioner Raymond Kelly said the questioning began as "a good-faith effort on the part of some people in the department to help us determine what resources are needed to police certain demonstrations in the future." It is being stopped, he said because, "we determined that was not that necessary."

While applauding Kelly's decision, the Civil Liberties Union still has concerns about who called for the interrogations and what has become of the information collected. "People have every reason to worry about what the government is doing with information it has no business having," says Lieberman.

A NATIONAL CRACKDOWN

The actions by the New York City police reflect moves at the national level since September 11. The federal government has generally targeted people for their ethnic background, rather than their politics. It has also taken action against mosques and Muslim organizations it believes are linked to terror, such as a Brooklyn mosque that prosecutors charge funneled money to Osama bin-Laden.

But the U.S.A. Patriot Act has allowed wider use of wiretaps on U.S. citizens. The FBI has received increased power to monitor meetings, oversee internet use and send undercover agents into houses of worship. The draft proposal for so-called Patriot II, with its provision for stripping people of citizenship, has sparked alarm among a wide array of organizations.

Attorney General John Ashcroft has said law enforcement needs increased authority to fight terrorism but that, even in these difficult times, he will show "scrupulous respect for civil rights and personal freedom."

Others are skeptical. "Viewed separately, some of the changes may not seem extreme," Michael Posner, executive director of the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, said. "But when you connect the dots, a different picture emerges...Too often the U.S. government's mode of operation since September 11 has been at odds with core American and international human rights principles."

Even some progressives say the government, while making some questionable moves, has been restrained in light of the enormity of the September 11 attacks. "There has been no repression of dissent comparable to the measures adopted by [John] Adams, Lincoln or Wilson," Paul Starr wrote in the American Prospect. "We have neither mass hysteria nor mass internment, and public officials have been quick to condemn discrimination against Muslims and Arab Americans."

And New York, despite the often raucous nature of the debate, has remained relatively tolerant of dissent. In fact, says civil liberties lawyer Norman Siegel, the war has boosted discussion and protest. "I always thought of New York as the town of the big mouths," Siegel said recently . "Post 9/11, pre the war, I wondered, 'where have all the big mouths gone?'...With the war in Iraq, there has been more coverage of dissent and demonstrations."

In general, says Joshua Brown, a certain tolerance usually, though not always, characterizes New York's approach to protest. Like it or not, Brown says, New Yorkers cannot help but be exposed to a wide range of opinions. "The fact of being exposed to a range of different perspectives doesn't mean you accept these opinions but you are aware they exist."

And so, even in an era of orange alerts and Patriot II, that willingness to listen, and the steady infusion of new ideas, may well keep New York one of the world capitals of dissent.

For more information

Defend America

(U.S. Department of Defense newsletter about the war on terrorism)

M27 Coalition

(supports direct action, including civil disobedience, against the war)

Not in Our Name

(opposes war and crackdown on civil liberties)

Students United for American at Columbia University

(supports the war)

United for Peace and Justice

(against the war)