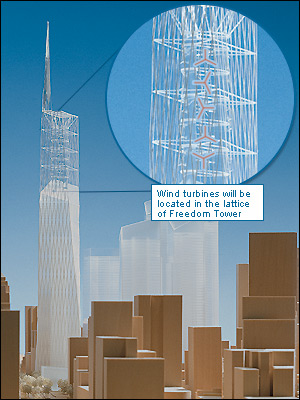

The latest design of the Freedom Tower at Ground Zero includes power-generating wind turbines in the upper section - or "lattice" - of the building. |

To the uninitiated, this might sound like a Don Quixote-like delusion; putting windmills in a skyscraper certainly has never been done before. But Freedom Tower's innovations are actually part of a trend. Whether the windmills prove feasible or not, a number of such environmentally conscious skyscrapers are going up across New York City. These so-called "green buildings," a term that is being used with increasing frequency, are designed to be healthier and more comfortable for the people living or working inside them. They aim to save energy, produce less pollution and conserve natural resources.

For years, New York builders were slow to embrace the idea of green buildings. But this is abruptly changing. "In the next three to four years," says Wayne Tusa of the U.S. Green Building Council, "the number of green apartments in New York City will rise from essentially zero to perhaps 3,000."

It's already happening. Just down the block from the proposed Freedom Tower, in Battery Park City, stands a residential high-rise billed as one of the most environmentally friendly in any city in the world. The Solaire, which opened last summer, features solar panels that provide five percent of the building's electricity; water for the toilets that has been recycled from the showers, sinks and dishwashers; and paints and adhesives that have no toxic or carcinogenic chemicals.

Advocates of such green buildings conjure up a city slowly filling with occupants paying less money for energy, feeling healthier and enjoying the knowledge that in some small way, their actions are making New York City an easier place to live and breathe. Critics question whether such features can ever have any significant impact on the environment in a city the size of New York, and whether they are worth the cost.

WHAT MAKES IT GREEN?

The environmentally conscious practices begin during construction, as builders seek out recycled materials and avoid those that give off harmful gases. (One such harmful material is particleboard, which is made with glues that give off formaldehyde.) And the builders recycle as much construction debris as possible.

Existing buildings can be renovated to consume less energy and be more environmentally friendly. For example, developers can keep the existing steel and the masonry frame, but replace the walls, windows and heating and cooling systems. In its New York offices, the Natural Resources Defense Council renovated a loft in the Flatiron District to emphasize natural lighting by adding a three-story atrium.

A former brewery in Brooklyn, now an apartment building, was renovated with a number of environmentally friendly features, including something of a meadow on its roof. Advocates of such green roofs say they keep buildings cooler in the summer and can also filter the air and rainwater, while providing a habitat for birds, butterflies and bees.

Once in operation, green buildings employ a variety of features that distinguish them from more conventional buildings. Some use solar panels to generate electricity and heat water; others put up windows that are double paned, filled with an insulating gas and treated with a special glazing that lets light but not heat pass through. Many of the buildings use special filters to clean more pollutants from the air than those in standard buildings. And in some, residents can take advantage of special storage areas for bicycles or landscaped roof decks, while the cleaning staff use products free of toxic chemicals.

Such practices, advocates argue, do more than benefit their occupants. Using less electricity can cut pollution from power plants and reduce, at least theoretically, the risk of a blackout that would affect all New Yorkers. In the same way, using less water helps everyone, especially during water shortages such as the one in 2002.

GREEN BUILDINGS IN NEW YORK

While outsiders might view New York City as the opposite of environmentally friendly, the city's very density means that residents use less energy and other resources than most Americans. "The city has long embodied many green principles," according to the Museum of the City of New York which is presenting an exhibition on "sustainable architecture" until January 19. As evidence, the museum cites Central Park, mass transit and the design of early skyscrapers. But it says, "In the post-World War II era, changes in zoning regulations and the widespread use of air-conditioning contributed to the design of glass-and-steel boxes...Wrapped in miles of inoperable, tinted-glass windows, high-rises housed office workers who, it was argued, no longer needed to be close to sources of natural light and ventilation. These buildings require massive amounts of fossil fuels to operate."

Some observers see signs that the attitudes that created such buildings are changing. They point to a number of buildings that have recently opened in the city.

The new high rise at 4 Times Square, popularly known as the Conde Nast building, boasts 1.6 million square feet of "environmentally conscious design," including circulating 50 percent more air through the building than is required by law and using non-toxic cleaning materials.

In residences, the poster child for green building is the Solaire. From the outside, the Solaire is almost indistinguishable from the neighboring buildings, but its guts -- the solar panels, the special air filters and so on -- are what make it special. In fact, some residents may barely notice the Solaire's unique features at first. Lyron Andrews moved into the Solaire not because he was looking for an environmental super-structure, but because he loved the serenity of the neighborhood, the acres of play space for his daughter and the striking views of the Hudson River.

But now Andrews and his family are grateful for other aspects of their new home. Andrews' 6-year-old daughter suffers from allergies. In their old apartment in Park Slope, she had to use an air purifier. But because the Solaire filters fresh air coming into the building twice, Andrews says, "After only one night in the new building, her allergies were gone, even without the purifier."

The Solaire is a luxury development. The eight-story building now going up at 1400 Fifth Avenue in East Harlem is not. Two thirds of its 128 apartments are reserved for buyers with annual incomes between $53,000 and $103,000, and many of the apartments will look out on a housing project. But like the Solaire, 1400 Fifth is considered to be among the country's most environmentally friendly urban designs. "Everyone deserves affordable housing that is built in a way that sustains the environment," says Carlton Brown of Full Spectrum New York, the developer of 1400 Fifth.

To do this, Brown starts with the premise that waste costs money. Well-insulated, tightly sealed windows will allow for a smaller heating and cooling system. While most builders make their walls on the construction site, Brown uses walls prefabricated in a factory. He also uses a lightweight composite recycled steel frame, which allows him to use less masonry. Such practices consume less material than conventional construction methods, produce less trash to send to the landfill -- and cut costs.

With that money, Brown says, "you can reinvest in those areas that will cost a little more," like recycled or renewable materials or a highly energy efficient heating and cooling system. (The heating and cooling at 1400 Fifth comes from a geothermal heat pump, a device that takes advantage of the relatively unchanging underground temperature of the earth, which is cooler than the air in the summer and warmer in the winter.)

Taken with the rest of the efficiency measures, 1400 Fifth is expected to eat up 70 percent less energy than a comparable multifamily building. "In the end, the costs about even out," Brown says. "A sustainable environment can be built at any income level."

And there are other environmentally sound projects that have been built with a close eye on costs. These include 299 East Third Street, a new affordable housing development in Alphabet City, and the award-winning Melrose Commons II affordable housing apartments in the South Bronx.

But expense remains a major concern. While developers of 1400 Fifth say the project will cost no more than a conventional building, The Solaire cost eight percent to 14 percent more than a conventional building of the same size. And its developer, Russell C. Albanese, recently told the New York Times that the 293 apartments in the building rent at about five percent above the going market rate.

It seems clear that, for now at least, green buildings will be hard pressed to succeed if they cannot keep costs down. A recent survey by Roper ASW found that few Americans are willing to pay a lot extra for environmentally friendly products. "If you look at the green consumer," environmental marketing consultant Jacquelyn Ottman told Indoor Air, the "consumer part is more important than the green part. People buy laundry detergent to get their clothes clean, not to save the planet."

And a Clifton, Virginia, developer has pointed out that most people looking for a place to live tend to focus more on location, the floor plan and nearby schools than on non-toxic insulation and energy efficient cooling.

THE GOVERNMENT ROLE

Cities such as Austin, Texas, and San Francisco have long featured environmentally sound construction, but the movement did really begin in New York City until recently, when the state and city governments began getting involved.

In 2000, Governor George Pataki unveiled a green building tax credit, the first one of its kind in the country, that has allowed some developers of environmentally friendly buildings to write off as much as $6 million on their tax bill.

The impetus for the Solaire came from the Battery Park City Authority, a semi-autonomous state entity, which in 2000 adopted some of the most stringent green building requirements in the country. When these requirements are applied to the next generation of buildings to go up in Battery Park City, they will make that area of lower Manhattan one of the most environmentally-conscious urban neighborhoods in the world.

Another big institutional booster has been the city itself. In 1999, the Department of Design and Construction developed a set of guidelines that encourage, though do not require, environmentally sound building methods for municipal projects. So far, the guidelines have led to 16 pilot projects with a total construction cost of approximately $700 million. One, the Queens Botanical Garden Administration Building, now under construction, will be a pioneer in the field. Among other features, it will include a system for collecting and reusing rainwater.

And most recently, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced a citywide competition that would give awards of $5,000 for environmentally conscious designs for various types of buildings. "With major renewal projects in Lower Manhattan, downtown Brooklyn, western Queens, Greenpoint/Williamsburg and the far West Side of Manhattan," said Bloomberg, "the need for sustainable development is as great today as in any time in our city's history."

Nothing going on in New York, though, will do more to affect the future of design and construction than the redevelopment of the World Trade Center site. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation has committed itself to incorporating sustainable design in the rebuilding plans, and the Port Authority has earmarked $100 million in capital funds for it. The details are slow in coming, and it is unclear how all this will ultimately be reflected in the final designs -- other than the wind-powered Freedom Tower. But if the most talked-about architecture on earth does indeed go green, it may create the kind of momentum that eventually persuades the entire New York construction industry to come around on the idea of building environmentally conscious apartments and offices.