Also in this series, four NYC congregations try to balance their religous missions with preserving their buildings:

|

With carefully chosen words and an inspired delivery, Reverend James Kowalski, the dean of St. John the Divine in upper Manhattan, urged his audience to support the world's largest Gothic cathedral.

The massive Episcopal church, which broke ground in 1892, the same year that Ellis Island opened, needs $20 million in repairs, the pastor said. In addition to being a house of worship, it also serves as a school, homeless shelter, soup kitchen, art museum, concert hall, and one of the most visited tourist destinations in the city - all of which costs money.

"We dare to say that we want to be a cathedral for all people," Kowalski said. "With your help, this cathedral will have more of the resources it needs to carry out that mission faithfully, respectful of the treasures of its architectural legacy."

But on this day, the reverend's exhortations were not aimed at his congregation nor was he trying to solicit contributions for the offering plate.

Kowalski was testifying before the New York City's Landmarks Preservation Commission. He was trying to broker a deal that would preserve the cathedral as a historic landmark and still allow the church to lease a portion of the surrounding grounds to Columbia University, which is interested in putting a 20-story building on the site.

The deal eventually fell apart.

Responding to an outcry from neighbors, the New York City Council rejected the arrangement in October, arguing that development would threaten the historic site. It was one of the few times in city history that the council overturned a landmarks designation.

The case of St. John the Divine is just the most recent example of conflict between advocates for historic preservation and religious institutions in New York City. The locations, architectural details, and religions vary, but similar issues often emerge. (Read profiles of four houses of worship across the city that are struggling to balance history and ministry.)

On one side are those who argue that many churches, synagogues, and mosques are historic treasures. In a sense, they say, the buildings belong to the whole city and must be preserved for future generations.

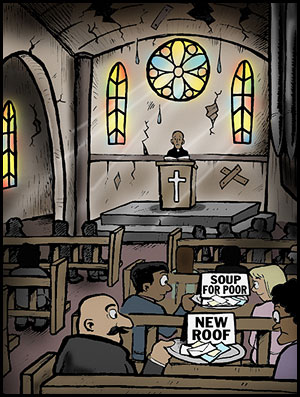

On the other side are religious leaders and congregations who argue that historic preservation can pose significant hardships. If all the money goes to maintaining century-old buildings, they contend, there is nothing left for charity.

BIRTH OF THE LANDMARK

In response to the demolition of Pennsylvania Station in 1963, Mayor Robert Wagner established the Landmarks Preservation Commission, a city agency charged with protecting sites and buildings that hold "special character or special historical or aesthetic interest."

Since it was founded, the Landmarks Preservation Commission has designated over 1,200 sites and 79 historic districts in the city.

Religious institutions are unique and must be preserved, advocates say. They are some of the oldest structures in the city, dating back to before the Revolutionary War. The spires, domes, and towers were often designed by the most prominent architects of the time, and interiors are decorated with rare craftsmanship and materials. They are also symbolic - not only for those who worship within their walls - but of the struggle for religious freedoms in America and the ethnic diversity of New York.

"Our religious institutions are treasures," said Robert Tierney, chair of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. "Historically, architecturally, and culturally - they make a major contribution to our city."

Some congregations welcome landmark designation because they fear the demise of their historic - and spiritually significant - places.

"Most of the time, older congregations want to preserve whatever they can and are desperate for the [landmark] designation," said City Councilmember Simcha Felder, who chairs the council's landmarks committee.

In Harlem, one congregation is currently trying to use landmark status to re-open its church, St. Thomas the Apostle, which the Archdiocese of New York closed in August. Each week, parishioners still gather to say prayers outside their padlocked building, and they protest in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral in midtown Manhattan. (Read more about the church.)

A LEGACY OF CONFLICT

There is also a long history of conflict between historic preservation and religious institutions in New York City.

In 1918, St. John's Chapel on Varick Street in lower Manhattan was demolished. Those who wanted to preserve the chapel included Theodore Roosevelt, Mayor George McClellan, and banker J.P. Morgan, but the rector of Trinity Church, which owned the property, said that "to care for ancient monuments of civic interest" was not the church's primary responsibility.

For the next five decades, many historic buildings - including churches and synagogues - were torn down to make way for new construction.

While landmark status preserves sites, it also carries additional regulations beyond traditional building and zoning codes. If a building or site has a landmark designation, for example, the owners must get approval from the commission before construction or even repairs can be performed. The commission considers issues such as how windows should be repaired, what kinds of materials are used to fix a roof, and where air conditioning units are installed.

And so some religious groups want to control their own properties and they oppose - or at least are wary - of landmark status.

One of the most famous conflicts in the city's history involved St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church on 51st Street and Park Avenue. In 1980, the church proposed demolishing its community house and replacing it with a 59-story office tower. Neighbors and preservation groups vigorously opposed the idea. When the Landmarks Preservation Commission blocked the plans, the church sued the city, citing the First Amendment. The legal battle lasted until 1991, when the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the city.

CHURCH VS. STATE

For some religious leaders, historic preservation - at least as it is currently practiced under New York City law - is a violation of basic religious freedoms.

Churches, mosques, and synagogues can be designated as landmarks even over the objections of religious leaders or trustees. In these instances, opponents say, the government is interfering with the mission and finances of a house of worship.

"Every dollar that comes into a church is for the purpose of ministry," argues Reverend N. J. L'Heureux, director of the Queens Federation of Churches and chairman of a lobbying group that opposes landmark status for religious properties. "The government should not be able to come in and say that those religious dollars must be used for museum creation."

During the New York City Charter revision process in 1989, L'Heureux's group, the Interfaith Commission on Landmarking of Religious Property, was successful in placing on the ballot an amendment to create a special, independent tribunal to hear the appeals of religious organizations that feel the Landmarks Preservation Commission has made unfair decisions. They unsuccessfully lobbied for a change in state law that would require consent of a church or synagogue before landmark regulations could be applied to a property. And in 1997, the group opposed a City Council law that would have allowed fines for failure to repair landmark designated buildings.

"The Interfaith Commission came to the conclusion that landmark status is one of the biggest threats to religious congregations," said L'Heureux.

Advocates for historic preservation argue that religion is not an exemption from the law.

"When a Catholic priest drives a car, he must have a drivers license; when a Baptist pastor hires a janitor to mop up, he must pay minimum wage; and when a Presbyterian minister invests money, he must abide by security regulations," said Kent Barwick of the Municipal Art Society. "Our society is governed by regulations."

Still in recent years, the battles over church-state land use issues have continued, even at the highest levels of government.

In 1993, Congress passed a law that exempted religious institutions from certain land-use rules on the basis that they might infringe on religious freedoms. The law was eventually declared unconstitutional.

And this past summer, President George W. Bush allowed federal grants to be used to renovate historic religious landmarks designated by the National Parks Service. Some are concerned it may break down church-state barriers by using taxpayer money for religious endeavors.

THE COST OF PRESERVATION

Most congregations are not primarily concerned with church-state issues, rather they feel threatened by changes in demographics and what they mean for their future.

In recent years, city congregations have lost members to the suburbs, neighborhoods have changed from one dominant ethnic group to another, and mainline denominations have seen drastic declines in attendance. Many churches, synagogues, and mosques simply don't have the money to maintain their buildings, and so they are looking for ways to generate revenue.

"We identified it as a crisis 25 years ago and it is still with us," said Anne Friedman of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, an organization that offers financial and consulting services to help preserve historic sites. "Particularly in New York City where real estate is so valuable, we will continue to see increasing development pressure on or near historic religious properties."

For example, West-Park Presbyterian, a 100-member congregation on 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, learned that it could cost up to $8 million to repair the roof and crumbling stonework on the outside of the church. The church's endowment will run out in two to three years, the pastor said, and current income cannot cover the costs. The congregation decided to explore selling the property to developers who would demolish it and replace it with an apartment building. (Read more about the church)

"When you are looking at repairs that are that large, you're faced with serious questions," said Reverend Robert Brashear.

Still there are resources and provisions to help religious institutions.

There are grant and loan programs to help churches, mosques, and synagogues. They don't pay taxes because of their non-profit status and many congregations also qualify for certain zoning exemptions. And the city's landmark law also includes a hardship appeal, a provision that allows religious institutions to challenge Landmark Preservation Commission decisions if they feel it presents an extreme economic situation.

"Most often it is not a case of some poor church in Bed-Stuy that wants to fix their roof and the city is telling them they have to use solid gold shingles," said Barwick. "These conflicts happen on Park Avenue, where someone says `we can make a lot of money for charitable purposes by selling off the building.'"

WHOSE HISTORY?

Just what is historically significant and who gets to decide what is important and what is not often fuels debate between houses of worship and their neighbors.

On West 70th Street and Central Park West, the city's oldest Jewish congregation, Shearith Israel wants to tear down its community center and in its place, erect a 14-story building, which would include a community center and 10 floors of apartments. The plan has drawn criticism from famous neighbors like ABC news anchor Peter Jennings and Pulitzer Prize winning author Robert Caro, who say that it would ruin the historic character of the neighborhood. (Read more about the synagogue.)

Shearith Israel's lawyer, Shelly Friedman, said that revenue from the new building would be used to help preserve the synagogue, its artifacts which date back several centuries, and its archives.

"If it is about how long one has been a resident of the neighborhood or who has walked past the building for the last 30 years, then a congregation that has been walking the streets since the 1600s should also have a voice," said Friedman.

CHARITY VS. PRESERVATION

Most urban houses of worship offer social services to the community - soup kitchens, homeless shelters, schools, senior citizen centers, and day care.

A study by the nonprofit group Partners for Sacred Sites found that 90 percent of urban churches provide services to people in need, many who are not congregation members. Advocates for preservation argue that this gives the local government a legitimate role in ensuring that they continue to exist.

"These buildings are centers for the community and belong to all the people," said Simeon Bankoff of the Historic Districts Council, a group that advocates for preserving specific areas of the city.

Some religious leaders contend that historic preservation efforts can threaten a religious institution's mission to help the poor and feed the hungry.

In Flushing, Queens, for example, the Bowne Street Community Church is currently divided over an effort to declare the building a city landmark. L.D. Clepper, a member of the church's governing board, said that the church had hoped to expand its community programs, including child and elder care and a soup kitchen, but that those plans have now been suspended pending a decision by the city. Too much money would be needed, he said, to do historic restorations. (Read more about the church.)

"The mission of the church is not to maintain historic landmarks, and this is forcing it on us by law," said Clepper.

THE POLITICAL FRAY

With religious institutions, neighborhood groups, historic preservation advocates, and developers all fighting for their interests, elected officials are forced to weigh in - and historic preservation can become intensely political.

In the recent case of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the issue was not whether the 111-year-old cathedral should be preserved; the city had been trying to designate the church as a landmark for years. The controversy was that the landmark designation coincided with the church's plan to lease a portion of the 11-acre grounds to Columbia University and to build two buildings, one that could reach 20 stories tall on the property. To allow for this, the Landmarks Preservation Commission decided to designate only the cathedral structure itself.

Critics say that the city failed to recognize the historic importance of the church grounds, but it also did not take into account that neighborhood residents and community groups have had a long - and at times contentious - history with Columbia University. Dozens of groups turned out to testify against the plan.

"There is a history of overlooking and ignoring important buildings in Harlem," said Maritta Dunn of the Harlem Valley Heights Community Development Corporation.

The City Council rejected St. John the Divine's landmark designation. Mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed the council's decision and the council quickly overrode the mayor.

"This cannot be the result that anyone would like to see," Mayor Bloomberg said in a statement.

After years of negotiation and debate, the process failed.

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine will not become a landmark anytime soon. The church is free to pursue its development plans under the city's regular zoning laws and officials said they would continue their discussions with Columbia University. And residents and neighborhood groups will have a more difficult time monitoring the construction in the future.

"Preservation should not be political," said City Councilmember Simcha Felder. "Landmark status should be a more pure, 'holy' process, but that's not the way it always turns out."

ALSO IN THIS SERIES

Four NYC congregations try to balance their religous missions with preserving their buildings:• Shearith Israel: Preserving The Past Or Shaping The Future? (Central Park West, Dist. 6)

• Bowne Street Community Church: Adapting To The Times (Flushing, Dist. 20)

• West-Park Presbyterian: Neighbors Come To The Rescue (Upper West Side, Dist. 6)

• St. Thomas The Apostle: End Of An Era (Harlem, Dist. 9)

RELATED LINKS

• Landmarks Preservation Commission• Municipal Art Society

• Historic Districts Council

• New York Landmarks Conservancy

• The National Trust for Historic Preservation

• "Ministry vs. Mortar" A Report by the New York Interfaith Commission on Religious Landmarking Religious Property