New teachers sink or swim. This is how educators have long characterized entry into the profession. But today the odds of sinking have increased exponentially. In New York City, 40 percent of teachers leave after three years, and 48 percent will be gone after five years, according to the United Federation of Teachers. (Nationally, the figures are 30 percent and 50 percent respectively.)

How did we get ourselves into this situation and how do we get out of it?

A TOUGH JOB

Teaching has never been the cushy job imagined by the public, which mistakenly believes that a teacher’s day ends when school lets out. People outside the field often do not seem to understand that teachers spend hours of additional time making lesson plans, reviewing homework, grading tests.

The profession also suffers from a lack of respect. Parents do not encourage their children to become teachers, and college graduates from our premier institutions view teaching as something to do for a couple of years after graduation before switching into more laudable and lucrative fields.

With increasing pressure on the educational system to meet the demands of a shifting labor market, more and more curriculum mandates and high-stakes testing make it difficult for teachers to be creative in the classroom.

But this already tough job is made worse for beginning teachers, who are typically given the most difficult assignments in the roughest schools. The most vulnerable teachers are handed what no one else wants. For example, the Teaching Fellows program was launched by the city’s Department of Education to staff the city’s lowest performing schools, those that the state classifies as Schools Under Registration Review. The department does this even though the fellows are the least likely of newly hired teachers to be graduates of schools of education.

Conditions for teachers may not have been better in the past, but times have changed. There are expanding opportunities for women who a generation ago saw teaching or nursing as their only career paths.

All of this helps explain why there is a shortage of teachers willing to work in our city's classrooms, though there is no shortage of teachers nationally (except in math, science and special education). The Department of Education has been forced to launch an extensive recruitment campaign, and has relaxed the requirements for these new recruits. This is why, of the 8,000 new teachers who enter the city's schools each year, about 2,500 come in with absolutely no teaching experience, not even as student-teachers.

WHY EXPERIENCE MATTERS

How can we expect people with minimal preparation to be successful in a profession that requires the skills of “parent surrogate, nurse, police officer, detective, psychologist, mediator, bathroom monitor, toilet paper dispenser, janitor, room decorator, quartermaster for school supplies, manager, organizer, lesson planner, cheerleader, lunchroom monitor, negotiator,” as one experienced teacher has put it.

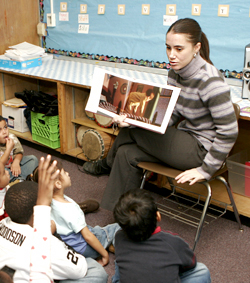

Teaching is all about relationships — the building of relationships between teacher and students. That’s why it is so hard. One elementary school teacher must have relationships with up to 35 very different individuals, each with diverse learning styles, needs, and levels of engagement. A high school teacher will typically teach 150 students.

There is research on the extraordinary number of decisions that a teacher has to make at any given moment —- more decisions minute-by-minute than a brain surgeon. The most conservative estimate from this data has teachers making approximately 130 decisions per hour during a six-hour school day, and this reflects only those decisions made within the classroom. This is extraordinarily daunting and often intimidating for new teachers. It makes support from administrators and colleagues so vital.

HOW TO KEEP NEW TEACHERS

Teachers Helping Teachers

According to a recent MetLife Survey of The American Teacher, the role of supportive relationships is the most important factor in helping a new teacher become a successful teacher. Today’s corporate world may emphasize teamwork, but many teachers remain in isolation in their classrooms.

According to a recent MetLife Survey of The American Teacher, the role of supportive relationships is the most important factor in helping a new teacher become a successful teacher. Today’s corporate world may emphasize teamwork, but many teachers remain in isolation in their classrooms.

Teachers Network, the non-profit organization where I work, has published numerous studies of the impact of teacher collaboration. For example, Sarah Picard, a teacher new to second grade, documented how her collaboration with an experienced teacher led to success in her Lower Eastside classroom. What began as informal sessions between the two of them to talk about children’s progress turned into regularly scheduled weekly meetings to investigate individual students’ reading abilities. These sessions became the two teachers’ main tool for understanding children’s progress and helped them choose strategies to support their students’ learning. The collaboration continued throughout the year and, by June, 93 percent of Picard’s previously-struggling students were reading on grade level.

At Manhattan Comprehensive Night and Day High School, Penny Arnold created a study group for colleagues who, like her, supervised student teachers. The teachers reported that, as a result of these conversations, they were better prepared to help their student teachers. The high school classes in turn benefited by exposure to new ideas, more attention, and better planning.

A variety of methods foster teacher collaboration and so can help change the nature of schooling. Team teaching, team planning, and such programs as the Bronx teacher leadership program in which teachers share classroom assignments so they can also take on leadership roles in the schools, will radically change our model of schooling. Teachers will no longer be on their own behind closed doors.

Teachers as Leaders

Teachers themselves can assume leadership roles, mentoring new teachers, designing and facilitating professional development for colleagues, serving as grade leaders and department chairs, and becoming members of school leadership teams.

Just as young, bright people in the business world succeed with proper mentoring, new teachers require mentors —- not buddies, but veteran teachers who have been carefully selected and fully trained. Building this relationship takes time; teachers say they need a minimum of five years to feel competent and confident in their classrooms. So, a one-year program would be insufficient.

The Role of the Principal

Effective leadership in schools is also critical. The best principals are veteran teachers who can present model lessons, coach teachers and lead informed discussions on teaching and learning. They remain connected to the classroom and can relate to their teachers and the students. Good principals create structures for teachers to work as a community. They provide resources — time, funding, space, and support — for collaboration, and they treat teachers as professionals.

Effective leadership in schools is also critical. The best principals are veteran teachers who can present model lessons, coach teachers and lead informed discussions on teaching and learning. They remain connected to the classroom and can relate to their teachers and the students. Good principals create structures for teachers to work as a community. They provide resources — time, funding, space, and support — for collaboration, and they treat teachers as professionals.

This differs from the traditional principal who too often ruled autocratically. It also differs from the current trend of quickly moving fledgling teachers into administrative positions. Can such relatively inexperienced principals serve as instructional leaders? Deputy Chancellor Carmen Fariña often cites her 22 years as a classroom teacher as the number one reason for her success as a principal, a superintendent and currently as the city’s educator-in-chief.

Lessening Load, Increasing Pay, Fixing School Buildings

Schools have to reduce the teaching load for new teachers and stop giving them the assignments that no senior teacher wants. New teachers need to observe other more experienced teachers, but this is impossible with a full teaching load. Changing this and lessening demand on new teachers will require incentives for senior teachers to take on the tough assignments. The teachers union has advocated pay differentials for experienced teachers willing to work in hard-to-staff schools.

Ultimately, schools alone cannot do all it will take to attract and keep new teachers in the profession. We need to ensure that teachers have decent working conditions. Too many schools need renovation, are overcrowded, and are sorely in need of modernization, including up-to-date science laboratories and technologies. Teachers need to be paid enough so they can afford to live in the city where they teach. And -- here is a “no cost” item -— we have to start respecting teachers, turning what has become a thankless job into an honored profession.

Ellen Meyers is senior vice president of Teachers Network, a national nonprofit organization that supports teachers to improve student learning.Â