Examination of diseased cattle by the members of the Board of Health, 1868.

NEW YORK – In September 2006, the city’s Board of Health announced it was weighing whether to require chain restaurants to post calorie information on their menus.

The goal of the regulation, the city’s Department of Health argued, was to address obesity – at the time more than half of adult New Yorkers were said to be overweight or obese.

The industry mobilized to stop the plan. Weeks of debate and a public hearing followed. Mayor Michael Bloomberg loudly championed the proposal and, in December, the Board voted unanimously to amend the health code with the new regulation, spurring the restaurant industry to unsuccessfully sue to stop it.

Ë™

Tomorrow, the Board of Health will hear from the public on another contentious proposal aimed at tackling the obesity crisis -- a ban on the sale of soda sizes larger than 16 ounces at restaurants, mobile carts, delis, movie theaters, arenas and stadiums or any other venue that receives a city health inspection. The proposal has stirred up the hostility of the beverage industry.

Critics and other observers say they expect the script to largely follow previous efforts to pass new regulations, with the final decision up to the Board’s group of 11 physicians, public health experts and scientists, including the health commissioner _ all appointed by the mayor.

James Colgrove, a public health historian and the author of “Epidemic City: The Politics of Public Health in New York,” said that since its beginning the Board has had “very sweeping powers” – but that it had grown increasingly influential under the Bloomberg administration.

“Bloomberg has made public health a centerpiece of his mayoral administration in a way that no other mayor has,” he said.

Some elected officials – including City Council members – and business leaders have criticized the Board's increasing importance.

City Councilman Daniel Halloran, a Republican, said the soda ban regulation was “going to be done strictly by fiat.” He added: “Any time we are going to regulate like this, I think it’s something that the elected officials need to vote on.”

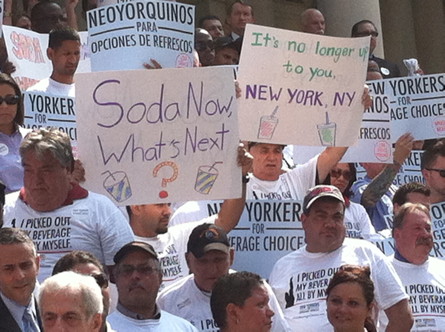

At a rally to oppose the soda ban at City Hall today, he said: "The agency's already made up its mind. Having the hearing is pointless."

A business and industry-backed group that sprung up in response to the proposal and has waged a campaign to stop it agreed that the Board would be unlikely to oppose the mayor.

“We believe that there should be a vote of the City Council. It represents the citizens of the city,” said Eliot Hoff, spokesman for New York for Beverage Choices. “The Board of Health answers to Mayor Bloomberg.”

The mayor’s office said the Board was the appropriate venue for the proposal.

“The Board of Health was designed to make public health decisions based on science, not political pressure, and that's just what it will do,” said Samantha Levine, a spokeswoman for the mayor’s office.

ATTACKING OBESITY

According to the Department of Health, more than half of New Yorkers continue to be overweight or obese – in spite of efforts by the city to encourage healthier eating and lifestyles.

Among the many indicators that obesity has reached a crisis point in the city include data showing diabetes has increased 16 percent between 2002 and 2010 and that about 5,800 deaths are linked to complications from it.

Obesity also disproportionately affects low-income and minority communities – and it is costly, with about $2.7 billion spent in Medicaid expenses in 2006.

The proposal for a soda ban came out of discussions of a task force convened in January by the mayor’s office to aggressively address obesity that involved the commissioners of 11 city agencies.

The task force announced 26 recommendations in May, including the installation of 700 new water jets and salad bars in schools; a push to create new urban agricultural sites; encouraging markets to publicize healthier alternatives to junk foods; and evaluating all city construction projects for opportunities to design buildings to encourage an active lifestyle.

But it was the proposal to establish a maximum size of sugary drinks that galvanized the attention of the beverage industry and commentators across the country.

If passed, it would apply to non-alcoholic, sweetened beverages that have more than 25 calories per 8 fluid ounces and less than 50 percent milk.

On The Daily Show, Jon Stewart joked that the proposal “combines the draconian government overreach people love with the probable lack of results they expect!" In contrast, filmmaker Spike Lee said he was in favor of it, calling obesity “a major, major problem in this country.”

The beverage industry raised the specter of overregulation – and even ran a full-page ad in newspapers of Bloomberg dressed as a nanny.

A group of 14 council members wrote a letter to the mayor on June 1 announcing their opposition. It was clear almost immediately that the Bloomberg administration would bypass the City Council and go to the Board of Health to get the ban passed.

“Many responsible, healthy, New Yorkers choose to consume soda in moderate amounts on certain occasions such as at a movie or baseball game,” the letter read. “Drinking a 20 ounce bottled soda with lunch is standard practice for many New Yorkers and does not necessarily reflect an unhealthy lifestyle.”

Councilman G. Oliver Koppell, who was among those who signed the letter, said that when a public health matter was complex and required specialized medical knowledge, it was understandable that the Board of Health would make a decision about it.

But he said that, in this case, the Council should have had some say in the matter.

“It's a decision about how far government should go in regulating people's lives,” he said. “I think it is appropriate … for a legislative body representing the people’s view to be heard.”

At a June 12 hearing, the Board of Health largely proclaimed its support for the proposal – although there were questions and some objections raised by the members.

“I just want to second the concerns about excluding juice, even 100 percent juice, and milk-containing beverages,” said Dr. Joel Forman. He said those drinks “have monstrous amounts of calories in them.”

Dr. Sixto R. Caro, another board member, said he was concerned that smaller businesses in lower-income neighborhoods would be unfairly burdened by the proposal.

In the end, the board voted unanimously to hold its only public hearing on the matter and to take comments.

Hoff, the spokesman for New York for Beverage Choices, criticized the timing and place of the meeting , saying that 1 p.m. on a Tuesday was problematic for businesses that attract a lot of customers during that time.

“It’s in the middle of the day in Long Island, Queens,” he said. “It’s not convenient for different parts of the city.”

He said hearings should instead be held in all five boroughs.

However, comments on the proposal can be made online as well.

FROM YELLOW FEVER TO OBESITY

The first Board of Health was formed in 1805, in response to Yellow Fever that had killed thousands in nearby Philadelphia. The Department of Health was created in 1870, with the Board overseeing the new division of government and the city’s powerful health code.

From the 19th to the 20th centuries, the Health Department focused most significantly on addressing infectious and chronic diseases.

The city’s health officials won pioneering battles to decrease child mortality rates, implement lead poisoning testing for children and battle AIDS.

Meanwhile, the Board’s almost unhindered oversight of the health code remained in place.

Colgrove, the public health historian, said the current focus of the Board and the Department on obesity and other so-called lifestyle diseases was appropriate.

“They are continuing the tradition that they've had all along: It's their job to protect people from what makes them sick,” he said.

Over the past few decades, the Board had on occasion become a locus of controversy – for instance, in the 1990s, a health code change allowed the Department of Health to detain those infected with tuberculosis to be detained as a last resort for treatment.

But it was not until Bloomberg came into office in 2002 that the authority of the Department of Health and, in turn, the Board, was used so assiduously – and some would say brazenly – to pass public health measures.

These have included smoking bans in restaurants, bars and, last year, parks and beaches; a ban on trans-fats in restaurants; and, of course, the posting of caloric information on menus.

The Bloomberg administration has not always gone straight to the Board, however, to change the health code, instead seeking out the support of elected officials.

But while the City Council could, in theory, pass some of the same regulations to protect the public health, it might behoove the mayor and health officials to stick to the Board.

“Strategically, you might say it is in the city's interest to do it through the health code because it is easier,” Colgrove said.

____

Nina Goldman contributed to this report.