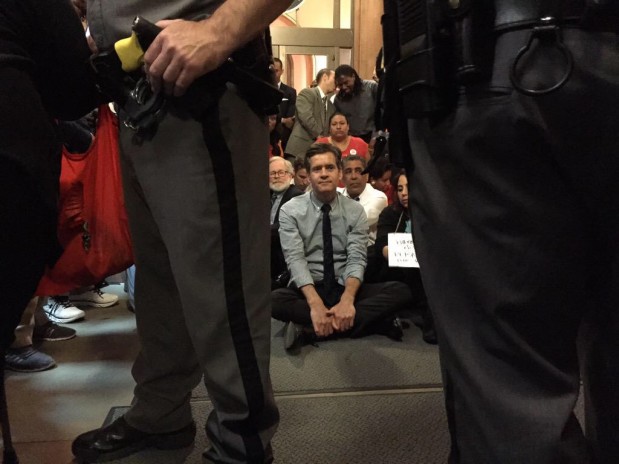

Mayor de Blasio at Rikers (photo: @NYCMayorsOffice)

The suicide of 22-year-old Kalief Browder has heightened scrutiny and intensified calls for reform of the city's bail system. Even prior to Browder's death, the New York City Council had been planning to consider new and proposed reforms at an oversight hearing set for Wednesday, June 17. Chief among those reform ideas is one introduced by Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito to create a $1.4 million city-wide bail fund for nonviolent, low-level offenders.

Each year, tens of thousands of New Yorkers like Browder are detained at the Rikers Island jail facility when they are unable to post bail. According to the Department of Corrections, 53 percent of inmates taken into Rikers in 2014 were admitted only because they could not pay bail, which is often $1,000 or less. These detainees totaled about 38,000 last year. Those calling for reform say that these jailings are unnecessary and are proven to have dramatic, life-altering negative effects on those individuals, including loss of jobs and housing.

Accused of stealing a backpack, Browder was 16 when he was arrested in 2010. With his family unable to pay his $3,000 bail, he was sent to Rikers Island for pretrial detention. Browder spent the next three years there, including more than 400 days in solitary confinement, until charges against him were dismissed. Browder was released and struggling deeply with the legacies of his time in jail. Following the news of his death, elected officials including Mayor Bill de Blasio and Mark-Viverito cited Browder's story as a "call to action."

"I think his case was an eye-opener to New Yorkers across the board," de Blasio said on Monday. "There is no reason that someone should be held for a long period of time if they can't pay bail and we can help on a modest bail level like that."

De Blasio expressed support for "some type of bail reform" and said there'd be more news "in the coming weeks." Before this past Wednesday's full-body City Council meeting, Mark-Viverito invoked Browder and again emphasized the urgency of reform, noting the upcoming oversight hearing.

"We need comprehensive criminal justice reform and we need it now, here in New York City and across the nation. We cannot throw away any more time or any more lives," Mark-Viverito said. Afterward, she choked up speaking of Browder on the Council floor, where she again promised relevant reform.

In a statement to Gotham Gazette on Thursday, Mark-Viverito said, "Far too many New Yorkers suffer the long-term consequences of incarceration – though innocent in the eyes of the law – simply because they cannot afford to post a low bail while awaiting trial. A broken system that unfairly subjects our young people of color to senseless abuse and violence is unsustainable. The New York City Council proposal for a citywide bail fund would ensure that qualifying individuals can get home to their families, reducing the number of lives that would be forever marked by a needless stay in jail. I look forward to a productive hearing examining much-needed and long-overdue bail reform in New York City."

In her February State of the City address, Mark-Viverito unveiled her fund proposal, saying, "because the overwhelming majority of those in jail are there because they can't afford bail—often as little as $500 to $1000 dollars—we will work to create a citywide bail fund." On Wednesday, she, her Council colleagues, and others who testify will evaluate the current system and envision a new one.

"The central thing we're working on is the nightmare known as Rikers Island," Council Member Rory Lancman, chair of the Committee on Courts and Legal Services, which will hold the hearing along with the criminal justice committee, told Gotham Gazette. "And at the core of Rikers Island problems are these extraordinary numbers of people who are there because they can't make a small amount of bail. So we will be looking at the system for assigning people bail, what amounts of bail are spent for people, what defines a bail mechanism or offer to defendants, and what alternatives there might be to the bail system as we know it."

Representatives from the Mayor's Office of Criminal Justice and the New York City Criminal Justice Agency, a private non-profit agency contracted by the city to interview defendants before their bail is set, will testify at the hearing. Lancman also said that the city's district attorney offices may send people to testify.

The Council will also look to evaluate supervised release programs, which are "designed to provide the courts with an opportunity to release some defendants under community supervision as an alternative to bail setting," according to the Criminal Justice Agency's report on its supervised release program in Queens.

"We are very interested in getting their feedback as to how they believe those programs are working, what the completion rates are," Lancman said. "I'm very interested in what the re-arrest rates are...we want to make sure [those released are] not out there committing new crimes in the community and we've heard some statistics that give us pause."

Critics: System denies poor defendants justice

Under current New York criminal procedure law, judges must consider whether a defendant is a flight risk when setting bail. Defendants are asked to pay bail money to be released and to ensure that they appear at future court dates. If the defendant continues to show up to court, the money is returned at the end of their trial. If the defendant fails to appear, they lose their bail money.

To assess flight risk and determine bail, judges often use the recommendation made by the aforementioned Criminal Justice Agency (CJA), as well as those from both prosecutors and defense attorneys. CJA details defendants' past history, including prior convictions and missed court dates, ultimately making a recommendation as to whether or not the defendant should be released on their own recognizance - meaning the defendant does not have to pay bail but issues a written promise that they will return to court for their upcoming proceedings - issued a bail demand, or locked up without the opportunity for pretrial release.

In far too many cases, critics argue, setting even a fairly modest bail demand is tantamount to pretrial detainment because defendants are of such modest means. In a statement to Gotham Gazette, Council Speaker Mark-Viverito said, "We have already paid a high price, as a city and as a society, for policies that senselessly incarcerate and abuse a generation of young people who have not been found guilty of a crime."

In New York City, the median bail amount is $5,000 for felonies and $1,000 for non-felony cases, according to CJA's 2013 report. Bail amounts can vary widely from judge to judge and from day to day.

The CJA report shows that only 9 percent of defendants charged with felonies and 12 percent charged with non-felonies were able to make the required bail payment at their arraignment. Even in cases where the bail was $500 or less, only 23 percent of felony defendants and 15 percent of non-felony defendants were able to post bail. Defendants with smaller bail amounts are also less likely to be helped by bail bondsmen, professionals who collect a commission on the bail money that they pledge to the court on defendants' behalf.

Those unable to pay their bail are detained, entering a jail system and suffering at-times severe consequences, both at Rikers and on the outside.

Critics have billed the system as unfair to poor, low-level offenders - many of whom are often people of color. In 2013, New York State Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman submitted a proposal to the state legislature that created a "presumption of release" for non-violent offenders, putting the burden on prosecutors to prove that defendants should be detained because they will not return to court or because they pose a danger to public safety.

The proposal was not well-received by some Republicans in the state Senate, who control that chamber. "The last thing I would want to be doing is giving get out of jail free cards," State Sen. Martin Golden, a Brooklyn Republican, told the New York Daily News. The legislation has since stagnated.

According to Bronx Sen. Gustavo Rivera, a Democrat, the current system denies indigent individuals access to "a real system of justice." Rivera, who supports the creation of a city-wide bail fund, sponsored the 2012 Charitable Bail Law, which authorizes and regulates charitable bail organizations at the state level.

In a phone interview with Gotham Gazette, Rivera spoke of the unjust incarceration of individuals waiting for trial. A report by the Vera Institute of Justice determined that in 2013, half of the people jailed in New York City were being held on bail of $2,500 or less.

"These are individuals who are innocent until proven guilty, yet they're being held there as if they are criminals, many of them because they are poor, because they are unable to post bail," Rivera said.

In New York City, defendants unable to post bail before their trial are sent to Rikers Island, a complex currently consisting of nine operational jails. Rikers is also where prisoners serving sentences of up to a year are housed. For longer sentences, prisoners are sent to prisons elsewhere in the state.

In a recent New York Law Journal column, Council Member Lancman and his legislative counsel, Molly Cohen, write that "According to the Department of Corrections, on any given day about 78 percent of Rikers' approximately 10,000 inmates are pretrial detainees."

In opening the piece, Lancman and Cohen explain the thrust of renewed Council focus on the bail system, which will be taken up at Wednesday's hearing: "Our city deserves a bail system that not only ensures that defendants return for court appearances, but that does not punish people for their poverty, is not racially discriminatory, does not distort case outcomes and runs efficiently," they write.

A $1.4 Million City-wide Bail Fund

The city-wide bail fund would be modeled on the Bronx Freedom Fund, a non-profit revolving bail fund with a 98 percent success rate according to its one-year report released in November. (The Brooklyn Community Fund is a newer bail fund.)

The Bronx Fund was the first organization to be licensed under the Charitable Bail Law that permits organizations to post bail of $2,000 or less for defendants charged with misdemeanors. In New York, a misdemeanor is a crime for which an imprisonment of more than 15 days but not more than a year can be imposed - this includes offenses such as graffiti, endangering the welfare of a child, and third degree assault.

Alyssa Work of the Bronx Freedom Fund believes theirs is a model that can be scaled up. "I know that the need is very, very great and we're doing as much as we can with the resources that we have," she says. "And I do believe that with enough staff and with enough resources for bail itself, that it is a model that can work across the five boroughs."

Work also argues that a city-wide bail fund would save New York money as bail money revolves through; once a case is completed the recovered bail money returns to the fund to be used for future bail. "It's very expensive to incarcerate people at Rikers Island," she says. "Compared with that, the cost of implementing and running a bail fund is far lower."

The City Council points out that "taxpayers spend over $100,000 a year to maintain just one person on Rikers Island." As part of a new infographic, the Council also argues that only 12 percent of misdemeanor defendants post bail of any amount, costing the city "millions of dollars to unnecessarily house people who simply cannot pay their bail." Mark-Viverito and others seeking bail reform are often quick to point out that the changes they seek are not aimed at allowing violent offenders any additional leeway.

Work, of the Bronx Fund, cites both financial and other costs. "We're not even talking about the cost to people's lives which is a separate and serious issue," she said, pointing to the many cases where defendants have lost jobs, custody of their children, housing, or educational opportunities.

Creation of a city-wide bail fund will certainly take center stage at Wednesday's hearing - Mark-Viverito and others still want to see funds included in the fiscal year 2016 budget, the final details of which the Council and the de Blasio administration are still negotiating. A final deal is due on or before June 30.

Meanwhile, the heightened focus on the bail system is part of a larger discussion of the justice system. De Blasio and Mark-Viverito have both been focused - to varying degrees - on reducing unnecessary arrests, as they call them. De Blasio and NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton changed enforcement of low-level marijuana possession and Mark-Viverito is looking to add civil penalties for certain nonviolent offenses that only have criminal penalties as of now.

Kalief Browder's case, and his death, have not only increased scrutiny on the bail system, but also on Rikers Island, the source of much criticism and ire of late, including from the US Attorney's Office, the de Blasio administration, and the Council.

Eliminate Bail Altogether?

Amid the talk of bail reform, there are also voices calling for deeper change, including the elimination of bail altogether. Among these voices are those from the Pretrial Justice Institute, which has started a petition calling on Governor Andrew Cuomo to eliminate the practice of cash bail in all of New York. Executive Director Cherise Fanno Burdeen believes that this would prevent future tragedies like the suicide of Browder. "He would have been assessed for release pending trial," she says. "He would have likely been released because, really, he was charged with theft of a backpack. And his case would have gone to trial."

Calling the idea of a city-wide bail fund a "noble band aid," Burdeen argues it is not a necessary use of taxpayer dollars. "I do find it curious that one part of the city would create a bail fund to pay another part of the city," she said, referring to the fact that it would be a city bail fund paying fees to the city courts.

State Senator Rivera also questioned whether the bail system needs to rely on monetary collateral, saying that he hopes Browder's death will galvanize lawmakers to engage in a larger discussion about bail.

"It's not a positive thing that we have to talk about this when there's a person that's taken their life, more than likely because of the abuse he suffered spending a few years behind bars for doing nothing," Rivera said. "But I do think that now we should have a conversation about whether the bail system needs to exist at all."

Short of even discussing eliminating bail altogether, Republican City Council members have been resistant to the idea of a bail fund. "As a taxpayer, I don't want to be paying people's bail," Council Member Vincent Ignizio told the Staten Island Advance after Mark-Viverito proposed the fund in her State of the City address. Council Member Eric Ulrich of Queens agreed, telling CBS New York, "I don't know that it's a wise use of city tax dollars to be used as a bail fund to get people off the hook."

There are currently three Republicans of the Council's 51 members. A bail fund bill, if proposed, would likely have more than enough support to pass through council committee and the full council. Right now, the Council is exploring the program and looking to set up a system without new legislation.

Mayor de Blasio did not include funding for the program in the executive budget he released in May. Still, Lancman remains optimistic that the city will allocate money to create the bail fund.

"I think it's one of the central pieces of the speaker's and the Council's budget agenda and we're in the heart of hammering out the budget right now," Lancman said. "So I absolutely expect it to be a part of the budget that we will agree to by June 30."

***

by Catie Edmondson and Zehra Rehman, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette