Further Deregulation of 5G Technology Won’t Close the Digital Divide

Broadband for All (photo: Phillip Kamrass/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

Just before the new year, a representative of a little-known telecommunications infrastructure company, Crowne Castle, made the case in an op-ed at Gotham Gazette that the key to closing the digital divide in New York State is more deregulation.

No one would disagree with the author’s assessment of the underlying problem: the pandemic confirmed, in case anyone remained unconvinced, that access to high-speed broadband is indispensable in modern society. Remote learning is impossible without it, and hundreds of thousands of New York school children are being left behind because their households lack high-speed internet service. At a time when visiting hospitals or a doctor’s office can be literally life-threatening, broadband is critical for conducting telemedicine as well as securing vaccine appointments. Likewise, for small businesses pivoting to online sales in order to keep their businesses alive. And on and on. Further, nearly one-fourth of New York State households don’t have home broadband (a sad fact unmentioned in the prior op-ed).

Crowne Castle says telecoms are begging to deliver 5G wireless service to everyone and pins the cause of the digital divide on alleged over-regulation of 5G small cell infrastructure in New York State. Strip local governments of the authority to regulate access to public streets and property, remove allegedly excessive fees, and just like that, deployment of 5G wireless technology will magically close the digital divide.

Pretty seductive, eh? Well, don’t be fooled. In fact, Crowne Castle’s cure means doubling down on exactly what got us into this mess in the first place.

There are two primary causes of the digital divide, and both can be traced directly back to industry-driven deregulation of telecommunications over the past 30 years. First, the failure of broadband providers to build out high-speed infrastructure comprehensively and equitably has left an untold number of New Yorkers without access to high-speed broadband. In many rural and lower-income areas, telecom companies decided it simply wasn’t sufficiently lucrative to invest in new, high-speed fiber networks. The second major cause of the digital divide is that many low-income New Yorkers just can’t afford high-speed internet service. While 92% of New Yorkers with incomes of $75,000 a year or more have home broadband, slightly over 50% of New Yorkers who make less than $30,000 a year have it. The pandemic has highlighted the impact of this harmful inequity.

Contrast this dilemma with the construction of the original universal telephone network in the middle decades of the 20th century. When AT&T was a regulated monopoly, state and federal regulators ensured that every American home was served by telephone service and that service was affordable. But swept up in the deregulatory fervor of the ‘80s and ‘90s, the 1996 Telecommunications Act deferred to markets, which were dominated by self-interested mega-corporations, to deliver next generation technology to the nation. The theory was that if cable companies and telephone companies freely competed in the marketplace, consumers would get the most advanced telecommunications products at reasonable prices.

The theory was wrong. Allowing telecom companies to pick and choose where they wanted to compete meant that some communities—like most of New York’s upstate cities and many rural areas, never got telecom fiber that would compete with cable companies. Unchallenged by telecoms, cable companies in those areas failed to upgrade their already overpriced services. Much of New York State endures a cable monopoly, with service that is both crummy and expensive. And in many rural areas, there is no high-speed service at all—and no mechanism for regulators to force buildout. Telecom and cable companies demanded deregulation and received it on a platter; today’s digital divide is the result.

That’s why the additional deregulation proposed by Crowne Castle is precisely the wrong solution. New Yorkers should also cast a skeptical eye on the hype surrounding 5G. First, 5G service available today provides no solutions for rural communities where broadband is least available. A few providers are piloting fixed 5G for home service, but the technology faces significant obstacles to large-scale deployment. For example, the fastest 5G spectrum cannot penetrate trees and walls—and is therefore not a reliable substitute for wireline broadband.

Second, the promised speeds of more than 500 megabits per second are not available from every carrier and don’t even reach most urban consumers today. For example, Verizon’s heavily hyped “ultra-wideband 5G” delivers superfast wireless speeds only in parts of dense urban areas, whereas its more widely available 5G using low-band spectrum is actually slower than 4G LTE much of the time. Ultra-wideband 5G requires radio and antennas spaced just a few hundred feet apart because the spectrum only travels short distances. AT&T Mobility also relies on low-band spectrum and has faced similar criticism that its 5G speeds do not exceed its 4G network in many cases.

Finally, 5G is not cheap. To take advantage of ultra-wideband 5G, you must purchase a 5G enabled phone and there has to be a 5G network of small cells blanketing where you live or work. That hardly seems like a formula for increasing the availability of high-speed internet to low income New Yorkers.

The Communications Workers of America, alongside other consumer advocates and elected leaders, has been fighting for reasonable regulation of 5G deployment to protect workers and consumers as this new technology comes online. New York City in particular has implemented sensible, model regulations that require orderly deployment of small cells. The city has pushed carriers to build in low-income as well as wealthy neighborhoods, and has required small cell operators to be transparent about the construction contractors they hire and the safety and training of their workers. In contrast, in cities where 5G deployment is like the Wild West, operators have hung small cells seemingly randomly, without regard to aesthetics or safety, and in some cases have even drilled holes in the middle of public sidewalks to install poles to support the cells.

Can someone explain the critical thinking skills behind a contractor that would install a #5G tower in the middle of the sidewalk, impeding wheelchairs and parents with baby carriages? Outside of a historic building? And horrific sidewalk repairs ( I use the word repair loosely) pic.twitter.com/jVJyvMtxZE

— Commissioner Eileen Higgins (@CommishEileen) August 16, 2019

That preemption kicked in when I was still in local government, it sucks. Folks in my Miami Beach neighborhood are fighting with Crown Castle right now over 5G poles.

— Michael Grieco (@Mike_Grieco) August 17, 2019

Repeatedly over the last several years, the industry has tried to sneak small cell regulatory preemption into the state budget under cover of darkness, in an effort to nullify regulatory initiatives like the one in New York City. Wisely, state legislators have successfully rebuffed this maneuver each time, preserving the authority of the state’s cities and towns to promulgate sensible regulations to protect workers and consumers. That’s the way it should stay. New Yorkers should remain skeptical of claims that deregulation is a panacea for the digital divide, and instead focus on policies that can truly promote additional broadband buildout and universal access for low-income New Yorkers.

***

Bob Master is Assistant to the Vice President of CWA District One. City Council Member Francisco Moya is Chair of the Council Subcommittee on Zoning and Franchises. On Twitter @cwabobmaster & @FranciscoMoyaNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Let’s Honor Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. by Restoring Voting Rights to Tens of Thousands of New Yorkers

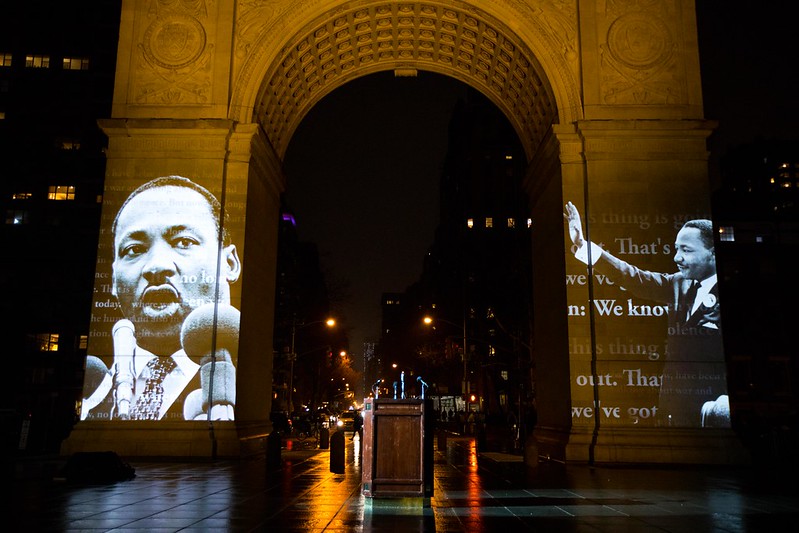

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the arc of justice (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayor's Office)

Today we celebrate the life of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and in July we will honor and mourn the first anniversary of the passing of Rep. John Lewis, who marched side-by-side at Selma and together championed voting rights as a key aspect of the Civil Rights struggle for Black people in the United States.

In recent weeks we have witnessed both the best of democracy -- massive voter turnout, particularly among Black Americans, overcoming voter suppression tactics to drive historic U.S. Senate wins in the deep south -- and the worst of democracy -- white supremacists running roughshod through the U.S. Capitol, leaving five people dead.

In recent years, across this country, we have watched in dismay as voter suppression tactics targeting people of color have regained a foothold through both laws and intimidation, with the support of powerful state actors and right-wing militias alike.

Preventing people from voting was such a significant strategy of Donald Trump’s failed re-election campaign that he went so far as to undermine the U.S. Postal Service in order to limit the efficacy of mail-in ballots.

Democracy is an act, the late Rep. Lewis stated in his final address to the nation. "The vote is the most powerful nonviolent change agent you have in a democratic society. You must use it because it is not guaranteed. You can lose it."

So what would you say if I told you that New York State retains in its laws a Jim Crow-era voter ban, written explicitly to disenfranchise Black people in the aftermath of formal emancipation?

The racial impact of the targeted disenfranchisement of individuals on parole cannot be overstated, given how generations of mass criminalization and mass incarceration have targeted Black and Latino communities. Criminal convictions have been used to suppress Black voters since the day we won even the most tenuous right to the franchise.

New York State, long a progressive beacon in the nation, must take a principled stand against this trend, to promote voting, especially in communities targeted for voter suppression.

One easy immediate fix is to codify Governor Andrew Cuomo’s executive order on voting rights for people on parole, through legislation currently on the table in the state Legislature (bill S830). The governor’s order provides pardons for the purpose of voting to most people on parole, and is a critical first step; but we must do more.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, only about 1,000 of the 30,000 people who newly received voting rights thanks to the governor’s order actually registered to vote, because of confusion in the process. In addition to ensuring that restoring voting rights is enshrined in the law, the bill would provide notice and an opportunity to register to vote upon release from prison.

There should be no confusion among eligible voters as to whether or not they legally have the right to vote. The continued success of our democracy, undermined substantially during the past four years, depends on this. Iowa, California, Washington D.C., and Florida took significant steps towards righting this wrong in 2020. Will New York State stand up and be next?

***

Rev. Kirsten John Foy is President and CEO of The Arc of Justice. On Twitter @KirstenJohnFoy.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We Need a Full Plan to Save the Arts in New York

Empty theatres abound (photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office)

Theaters shuttered—some will never return. Countless entertainment professionals in perpetual unemployment—fortunate if they still qualify for unemployment benefits or union-backed healthcare. An entire season of “A Christmas Carol” and “The Nutcracker” productions moved online.

The stage was set for Governor Cuomo’s announcement this week to revitalize New York’s critical arts industry—an economic engine, essential creative torrent, and source of joy, community, and soulful fortification for all of us, and an industry devastated as much as any by the pandemic.

While we applaud the governor’s attention to the arts and some of the commitments he made in his State of the State, it will take a lot more to support the arts—both the institutions and the individuals—than pop-up performances by Chris Rock and Amy Schumer.

Don’t get us wrong: prominent New Yorkers sharing their star power is a piece of the puzzle (and, if nobody’s doing this already, let’s turn their pop-up shows into a Made-in-New-York Netflix special, and commit the proceeds to support regional non-profit theaters as the recent online production of A Christmas Carol and fundraisers by the Actors Fund have done), but such celebrity events are the icing, not the cake; the sizzle, not the steak. And New York’s arts need a full buffet of innovative, well-resourced, ambitious efforts—as creative and nimble as our arts world itself.

We may not be Chris Rock, but we are enmeshed in the world of independent arts. As performance practitioners, producers, and non-profit board members (Justin, the founder and Board Chair of The Tank, a 17-year-old performing arts venue committed to tearing down economic barriers to presenting and experiencing new work; Tiffany, a Tank Board Member and Artistic Director of Elisa Monte Dance, a 40-year old Modern dance company committed to creating an inviting, welcoming and forward thinking environment for dance artists) we’ve seen the fate of too many independent venues before and know the juggling act we all do to survive. We’ve also seen how artists—backed by smart public policy—can sustain lives for themselves and art for the public.

So what can the city and/or state do? From grants and loans to small theaters to negotiating with and supporting landlords with non-profit tenants to programs that keep paid staff in their jobs, rather than sending them onto unemployment, to initiatives that care for freelancers and independent contractors who make up so much of our cultural ecosystem, there is no shortage of policy possibilities.

Give property tax breaks to landlords to pass on to small nonprofits, guarantee loans to back payroll, hire artists to become teachers' aides that support small cohort learning when schools reopen, use theaters as classrooms because we need more space, open public spaces up to public performances that operate within clear, sensible distancing rules—a policy-maker or legislator doesn't need to look far to see endless possibilities that could subsidize our cultural landscape and leverage our cultural capital to help sustain, nourish, and rebuild our city.

(Hint: many of these ideas could be great ones in the best of times as well as the worst of times.)

We're not pretending to know which policy is best. We're the creators—we know what our city and society needs, we're here to help create it, and support the thousands of artists that call The Tank home each year however we can, as we have been doing during the pandemic in which we’ve kept our staff employed, expanded the team, and continued to give artists a stage and a stipend. Right now, we’re here to challenge and partner with the policy-makers ready to make that happen.

Here are a few principles that lawmakers should look to in order to ensure the vibrancy of independent arts in New York:

1. Space is sacred. We need space to create, share, and experience art and culture. In the near-term, that may be outdoor space. In the long-term, it's knowing we'll still have our indoor ones. When the world is ready to come out of our homes and off our screens we’ll need to have spaces that are protected for cultural experiences.

2. Creativity isn't free. We don't go into art for the money, but creating art can't only be a game for the independently wealthy. We want to respect creators' time and work, compensate them, and allow them to build viable lives off their cultural contributions. That means backing venues that support artists, backing salaries of staff in these venues, and promoting policies—from tax policy to health care to worker protections—that support freelancers and independent contractors.

3. We're all in this together. Everyone, from the student in universal pre-K to the housebound senior at risk in this pandemic, benefits from live performance. Let's subsidize it to make sure it's accessible to all: from where it takes place to how much it costs. And let's make sure that everyone has access to creating—without financial obstacles, gatekeeping or other systems of marginalization slamming the doors on the next generation of performers.

4. It can't just be the big guys. We want Broadway to come back; we want the members of Broadway unions and staff at big theaters to be taken care of until it does, but we want to make sure any program doesn't just work for the big business of Broadway but for the huge constellation of small, independent venues. For artists just starting out, it’s these venues that make New York worth coming to in the first place.

5. Be Bold and creative! This is advice you’d give to any performer, writer, designer—let’s challenge Governor Cuomo to the same. The governor announced a plan to employ 1,000 artists—why not 50,000? New York is possibly the only city that could implement a program at this scale and still engage only a small portion of residents who make a living in the arts. Why not build a New Deal, WPA-style public works corps, or create a program that floods our schools with artists running enrichment programs in underfunded neighborhoods or even in-person, small-pod experiences for remote students?

Governor Cuomo suggested pop-up shows—let’s make them every Saturday night, in every town and city that can partner to host them, every week until the pandemic lifts, bringing together the headliners with the newcomers, giving a boost to the emerging artists on the coattails of our Empire State celebrities? Governor Cuomo talked about flexible seating—how about flexible real estate? A program to give empty spaces for a year to arts nonprofits, giving landlords life in their storefronts and covering utilities or insurance, then work with them to scale up to a mutually agreeable rent in subsequent years. Or borrow “cheap money” with interest rates so low and build and update arts venues across the state. Use union labor, put folks to work, and prepare for the next generation of theater- and concert-goers ready to emerge from the covid cocoon.

If we look at major legislative achievements in our history they relied on the combined efforts of everyday people, artists, activists, and legislators. Now is the time for a big achievement.

Independent performance spaces are the lifeblood of the cultural life of New York City, pumping ideas and creativity and talent through every fiber of city life. Small arts venues give performers their first stage—whether those artists are stepping up from the Bronx or busing in from Buffalo. These are the venues where you can take risks as a performer and learn your craft. It's where young and new audiences can afford to see shows. And these are the spaces from which the creators emerge who then shape our culture through theater, dance, film, music, and more.

There's no question that New York runs on cultural energy, from the bright lights of Broadway to the world-class concert stages to the glorious outdoor festivals. The city needs those venues open again, when it is safe for performers, staff, and audiences. But the cultural heart of our city can't beat again without the lifeblood running through it—so any plan to support Broadway or Lincoln Center or BAM needs to also ensure Off-Off-Broadway, independent music venues, rehearsal spaces, and the ecosystem of small performing arts spaces, come back. There is more than one way to be an artist. Not everyone wants to be The Metropolitan Opera or New York City Ballet. We need small and mid-sized companies, independent artists, collectives, and community-based art to create a healthy arts ecosystem.

In the best of times, independent spaces like The Tank exist on a razor's edge—a couple bad box office months away from insolvency or one greedy landlord from a rent hike and eviction. You can fill column after column with the names of the beloved venues that have closed in recent years: as prominent as CBGB’s and UCB, as quirky as the Zipper, Galapagos, and Shetler Studios—and those are the famous ones. In the best of times, it's the mix of community support, shoestring budgets, volunteer labor, staff devotion, and luck that keeps these venues alive. Having moved among more than half-a-dozen venues since our founding, we feel fortunate every day we are able to continue in our artistic mission.

So in the worst of times—which a pandemic is for the live arts—we're all in deep sh*t. Venues that eke by on $10 tickets are locked up tight and people should be able to experience quality art at this price. Volunteers and artists are facing their own economic and health crises. Landlords that want to be generous face their own financial crunch, as do foundations and donors. Companies that are too small to be taken seriously for loans may just blink out.

Think about what artists have contributed to New York City. In a time when the city is experiencing collective trauma, allow artists to do what we do best—heal, entertain, and bring out catharsis. When our city recovers—when, not if—we'll need these venues, or at least the people that brought these venues to life to help create new ones. And if those people flee the city or flee this industry or can't overcome their own financial insecurity to produce, support, and give their life to art, then our whole city will be the worse for it. Although New York is extremely competitive it is also a place where you can create opportunity. Dreams come true here. Everyday we are living ours.

The show must go on. The show will go on. We're not giving up on New York. We know New Yorkers won't give up on us. And we need New York—the government, institutions, power-brokers, policy-makers—to do the same.

***

Justin Krebs is the founder and Board Chair of The Tank and a candidate for City Council in Brooklyn’s 39th District. Tiffany Rea-Fisher is a Tank Board Member and Artistic Director of Elisa Monte Dance. On Twitter @justinmkrebs and @treafisher.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.