Police and Protest: 1992 and Today

NYPD officers (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

On September 16, 1992, roughly 10,000 demonstrators filled City Hall Park in a protest over police accountability. Marching around the park with banners and signs, they expressed their anger at New York City Mayor David Dinkins. After less than an hour, the protesters broke through the barricades around the park, storming the steps of City Hall itself, while another group of protesters filled Murray Street to listen to speakers who urged on the crowd.

A short while later, approximately 2,000 protesters marched onto, and occupied, the Brooklyn Bridge. They stopped traffic in both directions and assaulted members of the press trying to cover the story.

In stark contrast to the George Floyd demonstrations, there were no mass arrests that September day. No officers in riot gear “kettled” the crowd before storming them. There was no outburst of furious baton-swinging. No shower of tear gas or rubber bullets.

What was it that made this protest different? How do we explain the restraint, even the sympathy, with which the NYPD confronted the protesters?

The protesters were police officers.

The demonstration that took place that September was organized by the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association after Mayor Dinkins proposed an all-civilian police misconduct review board. Citizen-activists had been demanding a civilian review board to exercise police oversight since the 1940s. Though pressure mounted after each incident of police brutality—from the 1943 shooting of Robert Bandy to the killing of James Powell in 1964—the PBA fought off complete civilian oversight. When Mayor Lindsay modified the existing police-controlled review board in 1966 so that civilian appointees would hold the power, the PBA launched a successful campaign to defeat the changes through fear-mongering and a ballot referendum.

With Dinkins’ proposal, members of the NYPD were confronted with the real possibility of the civilian oversight and accountability they had so long resisted.

Police unions responded as they always had—by trying to kill the reform and maintain their power. The 10,000 off-duty police officers who demonstrated in lower Manhattan that September 1992 day was a show of force, a message that the city could have a review board or a police force, but not both. As the signs some officers were carrying that day threatened, there might be “No police!” if they did not get the “justice” they demanded.

Though Mayor Dinkins argued that the protest proved the need for civilian oversight, other prominent leaders seemed unconcerned. Despite demonstrators who were drinking and mounting cars, as well as uniformed officers who made little attempt to control the crowd, “law and order” advocates were largely silent. They did not decry the actions of protesters or proclaim that lawlessness was taking over the city. Indeed, mayoral candidate Rudolph Giuliani, a former federal prosecutor whose future administration would fiercely promote “zero tolerance” policing, took part in the protest himself. Philip Caruso, the PBA president, called for understanding the protesters’ actions. Though Caruso conceded “the emotional level did get a little out of control,” he pointed out that “sometimes if emotionalism is not evoked publicly, the responsible elements of the community do not listen.”

The police department’s contrasting responses to the 1992 PBA protest and the recent Black Lives Matter protests are revealing. Rhetoric to the contrary, the NYPD’s crackdown on protesters last month was not about maintaining public safety. It was—like the PBA protest of 1992—about power and control. Attacks on protesters were made in the same spirit with which police lashed out against a civilian review board in 1992. It was an assertion that citizens dare not question the police, nor demand changes. You either take policing as it is, or you might not get it at all.

This sense of entitlement to absolute authority is part of the broader problem of police culture in New York City and the United States. It is a culture that resists public accountability and rejects the legitimacy of external oversight. It is embodied in the “No Justice, No Police” signs that off-duty NYPD members carried that day in 1992, in the “Whose Streets? Our Streets!” chants heard from St. Louis police while citizens protested the not-guilty verdict in the 2011 police killing of Anthony Lamar Smith, and in bumper stickers emblazoned with the ultimatum “If you don’t like us, don’t call us.”

The 1992 anti-oversight protests were not an aberration, as the New York City PBA has continued to resist accountability and oversight. In 2013, in an attempt to end racially discriminatory stop-and-frisk policing, the New York City Council passed two accountability measures collectively known as the Community Safety Act. The PBA vehemently opposed the new laws, which were passed over vetoes by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and established an independent inspector general for the NYPD and made it possible for individual citizens to sue the department for discrimination. The union subsequently sued the City Council to overturn the laws while also suing to overturn a 2013 federal court decision that ruled the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk practices unconstitutional.

Throughout the last decade the PBA also repeatedly invoked Civil Rights Law 50-a to restrict public access to body camera footage and the outcomes of administrative trials. Though filing lawsuits and expansively interpreting legal codes may be tactically different from the 1992 City Hall protest, resisting oversight has remained the strategy.

In addition to taking legal action the PBA has continued to operate in the political arena to forestall oversight. In 2019 the PBA launched a “vote no” offensive against a series of ballot measures designed to strengthen the Civilian Complaint Review Board. Under the proposed changes police commissioners would be required to submit an explanation to the CCRB if the commissioner rejected the board’s disciplinary recommendations. As part of their campaign against the new accountability measures the PBA stoked fears over rising crime, claiming the new accountability measures “will make the city less safe.” In doing so, the union drew on a rhetorical pattern linking the potential for increased crime with increased oversight. Speaking to the New York Times in 1992 about the Dinkins administration’s reform efforts, PBA president Phillip Caruso predicted “crime is going to get worse, the streets will become less safe than they are.” Such rhetoric represents another tactic in the fight to delegitimize oversight and accountability.

There has been significant debate in the last few weeks over whether problems in policing reflect a few “bad apples” or a more deeply rooted, flawed system. The contrasting ways police have responded to protests and proposals over their authority shed light on the systemic problems. Dismantling a culture that demands unlimited authority and resists virtually all oversight is necessary if we are ever to move toward a more equitable system of justice in this country.

***

Kenneth M. Donovan is a PhD student at Stony Brook University and United States history teacher at Huntington High School.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Surveillance and the City: Cuomo’s Covid Security Theater

Governor Cuomo headed to Georgia (photo: governor's office)

For years, travelers have complained about security theater at our airports. Even as we’re forced to do everything short of strip naked for TSA agents, people are still able to sneak guns, grenades, and even the occasional venomous snake onto planes. It feels as if the point of the multi-million-dollar investment in mass screening is to give the illusion of safety, not safety itself. And so is the case with New York’s newest form of airport surveillance: COVID-19 registration.

In the earliest days of the pandemic, New Yorkers were eyed warily by other states as nothing short of 21st century plague carriers. Some states went so far as to call in the National Guard to monitor for New York license plates and even threaten to close down the border itself. But now that New York is on the far side of the first wave, the tables have turned, and now New York is looking at out-of-state travelers with suspicion.

The threat of interstate COVID-19 transmission is real, but New York’s screening offers only a false sense of security. Governor Cuomo’s new order requires those flying in from dozens of states to register with New York state government or face a $2,000 fine. Those arriving in cars, trains, and busses also must register, though with no one greeting them at arrival to ask and no clear penalty for failing to do so. And if either set of travelers violate the 14-day mandatory quarantine, they face a $10,000 fine.

While the state has doubled down on airport travelers, there is no plan to track other visitors. Many of those driving into the state don’t even know about the requirement. Even Governor Cuomo himself acknowledged that there is no enforcement mechanism and that no fines had been handed out as of July 14.

A law with no clear enforcement mechanism creates the risk of selective enforcement, often at the expense of New Yorkers of color and other over-policed communities. Recent efforts to add airport “enforcement teams” is more about optics than public health, as there is still no plan for reaching other travelers. Even worse, once this data is collected, it just sits in government databases, with no actual follow-up by public health officials.

But just because public health authorities seem to have no interest in using this data, that doesn’t mean collecting it is harmless. Whether its abuse by law enforcement, other government agencies, or hackers, travelers can’t know how their data might be abused. Cuomo’s rushed executive order answers none of the questions that lawmakers would address through the legislative process. The end result is this: sloppy executive orders with poor enforcement mechanisms and expansive ambiguity.

Targeting out-of-staters may be a good soundbite, but it’s not smart policy. New York still has COVID-19 community transmission, spreading the virus at July 4th parties and day cares. Blaming travelers ignores that New Yorkers aren’t doing enough to protect our state: wearing masks, maintaining social distance, and washing our hands. We don’t need fines, we need clearer guidance and better role models from Albany.

None of that is coming from Governor Cuomo, who recently flew to Georgia’s COVID hotspot. Cuomo could have chosen to register and show New Yorkers that he’s willing to practice what he preaches. Instead he flew a charter flight and cited a technicality to avoid his own order -- and even failed at times to wear a mask while near other people at a press event. Technically, the governor doesn’t need to register and quarantine, since he went for less than a day, but that’s a detail that isn’t grounded in the science behind the order and that many of those threatened with fines at our airport will never know.

The truth is that the governor never needed to get on that plane at all. He could have done what millions of New Yorkers (himself included) do every day, and hop on a call or video chat instead. But for the governor who has constantly craved good press in these terrible times, it’s just another example of public health taking a back seat to public relations. This is going to be a long, drawn-out crisis, and perhaps the only thing that will remain constant is the need to adopt COVID-19 policies based in science, not politics.

***

Albert Fox Cahn (@FoxCahn) is the founder and executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (S.T.O.P.) at the Urban Justice Center and a fellow at the Engelberg Center for Innovation Law & Policy at N.Y.U. School of Law. He writes the monthly “Surveillance and the City” column at Gotham Gazette. Caroline Magee is a rising third-year student at Emory University School of Law and a civil rights intern at the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Americans with Disabilities Act at 30: How Far We’ve Come and What’s Next

Activists call for accessible transit (photo: @CID_NYLevel)

Thirty years ago we fought for the passage of our civil rights law, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). We celebrate the ADA and what it has helped us achieve. Yet, we know that we still have work to do. Exclusion, discrimination, and inequality are built into every system that affects us and we are more severely affected if we are also Black, Latino, Asian-American, or LGBTQ. We look forward to welcoming the next generation of advocates, born since passage of the ADA. We encourage them to join us in ensuring the full realization of disability rights and justice in the next 30 years.

The Disability Rights and Justice movement, including independent living centers, fought hard for changes to barriers in our daily lives. We’ve won a lot since the ADA was passed in 1990. But, to achieve meaningful change, and to protect our rights we must continue the struggle.

Our actions since 1990 led to:

Better access to websites for voter registration and absentee ballots for people who are blind and more accessible polling sites and machines for people with all kinds of disabilities.

Requiring hospitals to provide American Sign Language Interpreters for patients who are Deaf.

Requiring that city homeless shelters come into compliance with the ADA.

Including people with disabilities in planning for and responses to disasters.

Requirements for landlords to lower elevator buttons, install braille, add ramps, etc. for tenants with disabilities.

Accommodating people with disabilities at movie theaters, theaters, and public attractions.

A fair shake for students with disabilities in a mainstream classroom or when taking college or graduate school exams.

Safer street crossings when curb cuts are put in and comply with the law.

People with disabilities having lives full of meaning in the community upon leaving institutions.

Employers leveling the playing field at work by providing necessary tools (a different desk, screen reader for the computer, etc.).

But, resistance to change persists. As new laws, regulations, and programs are created, we still see discrimination built into their fabric. And, many times, the issues that affect our lives are still invisible to others.

More changes need to be made. Accessible absentee ballots must work for everyone with a disability; more accessible and affordable housing would help bring people out of shelters and institutions to live in their communities; more elevator access in subways means more people with disabilities can get and keep employment; new buildings complying with ADA standards mean more people with disabilities can get services they need, work and participate in civic life; and better access to appropriate health care means better outcomes and a healthier population. We can ensure that children with disabilities are not denied full services to support learning in the classroom. We must end police killings of Black and Latino people with disabilities and using police to respond to mental health crises.

Have we achieved a great deal? Yes. Can we do more? We must. We are tired but tireless. We at Center for Independence of the Disabled, NY (CIDNY) will continue to advocate for and work with people with disabilities, and we are fortunate that we have allies to aid us along the way. So today we say happy birthday ADA. You’ve grown up, but you still have a lot of growing to do and a new generation to help make it happen.

***

Susan Dooha is executive director of Center for Independence of the Disabled, NY (CIDNY). On Twitter @CID_NY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

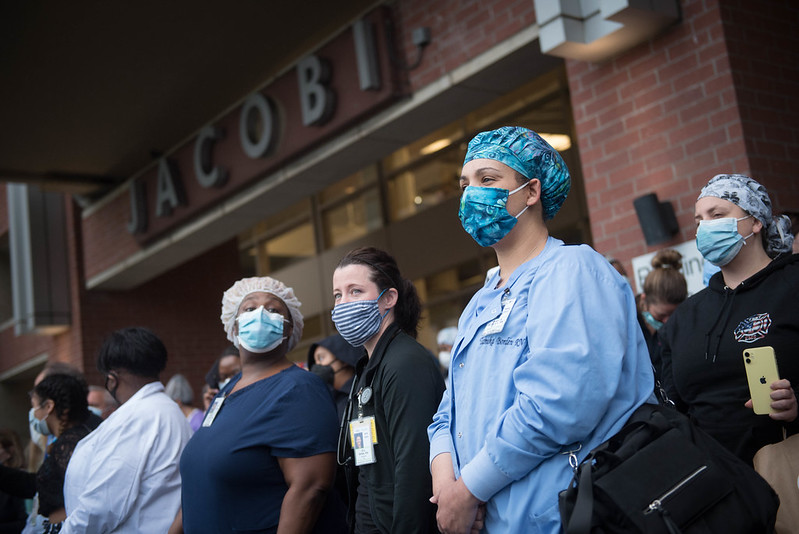

To Honor Essential Workers, Congress Must Save Public Transit

Nurses and other essential workers need public transit (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

I am a lifelong New Yorker and public transit rider. In March, when so many of my friends, family, and neighbors stopped commuting, I kept traveling to work. I depend on a bus and two subways to get from my Queens home to the East Side of Manhattan hospital where I’m a pharmacist.

Like most people, I had never heard of “essential workers” before COVID-19. Everyone I knew got up and went to work regardless of what job they had. And thankfully, many I know are still employed, though working from home. I found out that being an essential worker, besides fighting COVID directly, meant still having to commute while others sheltered at home.

As a commuter during COVID, I have depended on transit more than ever. Without a car, the bus and subways were my lifeline. Without public transit, I could not reach nor serve my patients. More this year than ever, I need reliable service. Especially when service was reduced for months, any delay became magnified and more frustrating than before.

I am so grateful for the transit workers who showed up so that I could show up too. It has been heartrending to hear of the losses among bus drivers, train operators and conductors. I don’t always think of myself as a hero just because I work in a hospital during a pandemic. But if I am one, the people getting me there every day despite everything are certainly heroes as well.

Now, as I watch terrified while COVID cases rise around the country, I also fear for my commute here in New York. I know firsthand how many fewer people have been commuting through the pandemic. I understand how much less money the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has from fares, and from tolls and taxes as well.

In March, New York’s Congressional leaders brought home $3.9 billion to keep trains and buses running through the worst of the pandemic in New York. But that money is nearly gone. The MTA is back to normal service and doing a lot more cleaning, still with relatively little money coming in. To avoid huge cuts next month, the agency needs another $3.9 billion.

In May, New York’s members in the House of Representatives put $3.9 billion for the MTA in the House’s $3 trillion HEROES Act. But Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell hasn’t taken up the bill. With COVID worsening nationwide, it now looks like another aid bill will start moving through the Senate soon. Congress must again take care of the MTA and people like me who depend on it.

Without more aid, the MTA will soon be short half the money it needs on a monthly basis. With a $17 billion annual budget, it could soon face a gap of $650 million each month. That’s a lot of trains and buses that would have to stop running.

To put it into perspective, the MTA’s last major cuts came in 2010 to save $400 million over one year. Today’s cuts could be 20 times larger than that. Last time, the MTA cut the V and W trains and cut or reduced service on 110 bus lines. In a report from 2011, they found that 15% of riders were inconvenienced by the cuts. A decade later, bus ridership had dropped 25%.

Cuts 20 times larger than those of 2010 could mean entire subway trunk lines shut down. The Riders Alliance recently produced a subway map with half the lines removed. Even if it’s not quite that bad, we could be waiting 20 to 30 minutes for trains during much of the day. Crowding would be very dangerous. Fares could rise by several dollars even as service is far worse.

Life as we know it in New York would be devastated if Congress does not rescue the MTA. We have already known so much unprecedented hardship this year. For essential workers like me, it is unimaginable what a cruel blow to the infrastructure we depend on would mean after what we’ve already experienced on the frontlines of COVID. It also makes me worry about some of our patients, who rely on public transportation to get to their medical care. The MTA cut would be another barrier for them to overcome to stay healthy.

Our influential leaders in Congress must stand up for us. We need our New York leaders in the House and the Senate to speak up now more than ever. They must tell their colleagues how letting New York’s transit system collapse would destroy our recovery and bring the nation down with us. Leaders like Senator Chuck Schumer and Representative Hakeem Jeffries -- and the entire New York delegation -- must use the great power they’ve built in Washington to save the commutes of millions back home in New York City.

***

Suk-Yee Wong is a pharmacist who lives in Queens and works in Manhattan.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Congress Returns; New York’s Future Hangs in the Balance

The U.S. Capitol (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

With Congress back in Washington, D.C., New Yorkers have a big stake in the outcome of the next federal economic stimulus package.

No Clear Signals on New Aid to State and Local Government

Serious negotiations are finally starting on an aid program to help an American economy devastated by the coronavirus recession. Two months have elapsed since the Democrats in the House of Representatives passed a $3 trillion aid package that included $1 trillion in support for state and local government, territories, and tribal nations across the country. The Republicans in the Senate are finally responding and are anticipated to introduce a bill soon.

The unique $600 a week supplement to regular unemployment insurance benefits that has aided tens of millions of Americans and shored up consumer spending expires on July 31, and in some states like New York, on July 26. While discussions are underway about an extension of some kind, there is considerable conservative opposition to continuing that generous benefit level.

With the election just a few months away, I cannot imagine there will be another stimulus package beyond the next one that is enacted before the November election (barring a national economic collapse), so whatever gets passed now will have to last many months.

New York State and City Have Enormous Budget Deficits

New York State, New York City, and the MTA all have immense budget deficits and need major help. The New York State government, responding to the plunging economy, adopted a budget in April with $10 billion in spending cutbacks, but has yet to implement most of that plan. The State Division of the Budget’s July 8 update says final details on cutbacks will be developed and notice given to service providers once the federal package is known.

The MTA is on the Brink of a “Four Alarm Fire” Crisis

The MTA is the most desperate of these three huge New York governmental sectors. In April subway ridership was down 95% as the lockdown began, and even last week was down 80% from normal, according to a July newsletter from New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer.

The MTA has described its problems as a “four-alarm fire.” Despite receiving $3.8 billion in the first round of Congressional support, it says it needs another $3.9 billion for the remainder of 2020, and shortfalls of $4.5-$8.7 billion remain through the end of 2021. The MTA will have little choice but to scale back some of its ambitious capital expansion plans, and may have to divert new tax revenue in a “lockbox” to help pay for those projects instead toward rescuing the operating system. If the MTA cannot get major new support from Congress, the state and the city will have to step up to help the agency as a last resort. The state authorized the MTA to borrow money to prop up its budget, but the agency is in such bad shape it may not be able to borrow the billions it needs and the state may have to borrow money on its behalf.

New York’s Lockdown Losses Are Staggering

The lockdown of the economy in New York State brought a staggering loss of 1.8 million jobs, including 900,000 in New York City, between February and April. Recovery has been slow and painful. The most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics update for New York, released July 17, showed the state regained about 300,000 jobs in June, after gaining about 100,000 jobs in May. Although the economy was regaining jobs, unemployment rates in New York rose in June because more New Yorkers re-entered the labor force than found work. The unemployment rate in the state rose from 14.7% in May to 15.4% in June, and the unemployment rate in the City rose from 18.3% in May to 20.4% in June.

2.6 million New Yorkers were on unemployment benefits at the end of June. Governor Cuomo remains cautious in allowing New York City to reopen, but New York’s slow reopening may end up with the state in a better position than other parts of the country where the coronavirus is exploding and parts of the economy are reclosing.

New York Has Taken Some Intermediate Actions to Address the Deficit

New York took limited action this spring to address its financial problems while waiting for help. The New York State Comptroller’s Office reported that state tax receipts were down 17% in June 2020 compared to June 2019. The State Division of the Budget, in the July 8 report cited above, said it will have withheld about $1.2 billion in local aid through early July, about half the rate necessary to achieve the full spending cuts in the adopted budget.

Governor Cuomo, during his daily briefings on the coronavirus this spring, said local aid cutbacks could reach 20% in education, 20% to hospitals, and 20% for other local government services that would imperil first responders, absent new federal support. The state budget also provided for $2 billion in state agency cutbacks.

New York’s Choices: Slash the Budget or Borrow

Whatever happens in Washington in the next several weeks, New York will face major challenges. New York doesn’t just face a $10 billion deficit this year, it faces a projected $8 billion deficit next year and continued problems thereafter.

The state government was authorized in the budget to borrow up to $11 billion this year, initially for cash flow purposes for just one year, but the law permits the state to extend that borrowing long-term. If federal aid is inadequate, New York will face the choice of slashing the budget or borrowing at least some of whatever deficit remains after federal aid has been provided to mitigate service cuts. The state may also have to bail out the MTA and consider the City of New York’s own request that it be permitted to borrow money for short-term operating expenses.

The New York City Adopted Budget’s Labor Provisions

New York City adopted its own budget in time for the July 1 start of the new fiscal year. It was filled with placeholders, the largest of which is $2 billion in new federal aid, which has not been passed and is the subject now at hand in Washington. The city budget also has a $1 billion placeholder for the de Blasio administration to negotiate savings in wages and benefits with the public employee unions. The mayor has said the city will have to lay off up to 22,000 employees beginning in October if it cannot achieve these savings.

The New York City Police Department ended up with modest cuts. Personnel moves will bring the size of the police officer force from 36,000 to 34,000, and the city has set a saving of $350 million in the police overtime budget. School security officers will be transferred from the Police Department to the Department of Education, which will reduce the police budget by $500 million, but the money will simply be spent in another agency.

The city used $4 billion in reserves to balance its budget, drawing down nearly all of its General Reserves, as well as about half the funds in a Retiree Health Benefits Trust. In the original proposed budget in April, the city projected it will have a $5 billion deficit next fiscal year, 2021-22, with little cushion left from its depleted reserves. Projected deficits for 2020-21 increased later this spring, meaning the ‘21-22 deficit could grow past $5 billion.

The adopted city budget did not anticipate any further cutbacks from the state government, despite the State’s Financial Plan with $8 billion in local aid cutbacks (which included other municipalities, not just New York City). The extent of aid in the federal package, therefore, will affect both the level of cutbacks from the state to the city, and the city’s own budget level.

The state and city both faced increased health care and emergency expenses above and beyond their normal budgets, but some federal aid from the original package is still untapped due to the failure of the Trump administration to provide guidance on how to spend the money and can be directed to provide relief.

The Answer, of course, is the Election: A New Progressive (or At Least Liberal) Government

Federal financial relief that just replaces revenue lost from economic decline can only last so long. If any relief package enacted now has a short duration, state and local government retraction is likely inevitable given how slowly the overall economy may recover from the virus. In the Great Recession, the Obama 2009 stimulus package expired in 2011 as the Republicans were coming back into power after winning back the House of Representatives in 2010. They restricted federal spending and the nation lost 500,000 jobs in state and local government over a several year period, slowing down the overall economic recovery. Let’s hope the same mistake is not made again, and that a new progressive government in the United States arrives to the rescue soon.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Police Reform Agenda for the Next City Council

NYPD officers on the scene (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

Watching racial injustice at the forefront of our national conversation in recent weeks has inspired millions of people across the nation to leave their homes and get involved in our democracy — some for the first time ever. Together, people in New York City from Brooklyn to the Upper East Side to Jackson Heights have all said enough is enough. It is time for city leadership to stand up and respond.

I am running for the New York City Council because I know we can do better than the system we have. The Council’s recent budget vote was a superficial attempt at change that missed the mark. We need real leadership on policing issues, not performative gestures and accounting gimmicks aimed at mollifying people seeking genuine progress. My plan aims to change the relationship between communities and policing, with the goal of engendering actual public safety, not a militarized city.

First, I will create a public safety task force for my district, which includes parts of the Upper East Side, East Midtown, East Harlem and Roosevelt Island, that is made up of community leaders and experts in policing. I will meet with these resident advisors on a monthly basis to develop immediate strategies for policing in the community, and create a long-term vision of what policing should look like in the City of New York.

Additionally, I will introduce legislation to create a five-year moratorium on the hiring of any new law enforcement officers by the city — that includes the NYPD, Corrections, and any other agency that has in-house policing. We are not going to solve the problem of over-policing in our communities while still adding to the payrolls of law enforcement agencies.

To further reduce these payrolls, we can offer early retirement incentives for people who are eligible, or near eligible, to retire, also saving the city’s deficit-ridden balance sheet. We also cannot balance the NYPD’s payroll on the backs of its non-law enforcement civilian workforce, which is largely lower-income, people of color who are not sworn officers. Changing our policing will not be accomplished with accounting gimmicks that target civilian, administrative staff.

I’ll also advocate for consistent budget cuts to the NYPD and other policing entities. The New York City budget is a statement of values as much as it is a financial document. Our community needs funding for senior services, affordable and public housing, transportation upgrades and accessibility, to name just a few important examples. I will advocate for equitable budgets that prioritize social services and defund over-spending on police.

Next, I will introduce a ban on any new law enforcement equipment acquired from the U.S. Department of Defense and mandate the city’s law enforcement agencies return any non-protective equipment (allowing agencies to keep basic materials like bulletproof vests or gloves).

Ending policing in our schools will be one of the toughest mountains to climb. In the era of school shootings we tragically live in, schools may need some level of security. However, students should not be subject to policing that could negatively impact them for years to come. We need to put a stronger focus on identifying students who are at risk of a mental health crisis before it ever becomes violent. We do need to prevent strangers from coming into school buildings and to address issues where non-custodial parents may seek to remove children from schools. But we must eliminate the school safety officers as we now know them. Students in schools should be safe from threats; they are not a threat. Law enforcement in schools in its current iteration must end.

This is not the end of the conversation or the work, but just the beginning. Billions of dollars need to come out of the city’s police budget and be invested in the tools that build stronger communities: education, the social safety net, good jobs and quality, affordable housing. We cannot lose sight of the need for policing to make communities safer, not menace the people who live there. Much needs to be done to create healing in our communities for people to feel truly safe. Let’s organize together to build the future New York we want to see.

***

Rebecca Lamorte is a Democratic candidate for New York City Council in Manhattan’s 5th District. On Twitter @RebeccaLamorte.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Must Address Racist State Violence from Policing to Jails and Prisons

A rally to end solitary confinement (photo: John McCarten/City Council)

On April 14, 60-year-old Leonard Carter died of COVID-19 while incarcerated at Queensboro Correctional Facility. He had already been granted parole and, after a quarter century behind bars, was just weeks from his release date. He was the brother of one of us writing to demand change here today.

While public attention has focused on the brutality of police in Black communities, that is just the front end of a system designed to control, dehumanize, and brutalize Black people. Calls to defund the police and dismantle systems of white supremacy must be expanded to include the institutions whose role is to criminalize, cage, and brutalize Black bodies, from prosecutors to the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision.

As a formerly incarcerated Black activist, a Black New York State Assemblymember representing Brownsville, Brooklyn, and the sister of a Black man who died of COVID-19 behind bars, we know that racist state violence pervades not just policing, but courthouses, jails, and prisons, too.

The anti-Black violence of our criminal legal system is not located in some far away city or state. Here in New York, Black people are more likely to have money bail set and be jailed before trial. We are more likely to be coerced into plea deals that include jail time. We are more likely to be incarcerated on a technical violation of parole or probation. We are more likely to be subject to the torture of solitary confinement. While only 18% of New Yorkers are Black, we represent 48% of people in state prison and 57% of people in solitary. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, 80% of people who died of coronavirus behind bars were people of color.

Earlier this month, New York’s Legislature repealed 50-a, a state law that had been used to shield police misconduct records from public view. This was a culmination of a years-long campaign led by families of people killed by the NYPD and a critical step towards greater police accountability and transparency.

But it was simply a first step. To achieve justice for Black people, we must fundamentally shift resources away from policing and systems of criminalization and towards the community investments that truly keep us safe: education, affordable housing, quality health-care, youth programs. At the same time, we must center the voices of marginalized Black people: Black undocumented people, Black incarcerated people, Black trans people.

The Legislature must not lose sight of the devastation wrought on Black New Yorkers by the full system of mass criminalization and state violence. In our fight to defend Black lives, we must repeal the “walking while trans ban” to protect Black and brown trans women from harassment by the police. We must pass the Protect Our Courts Act -- passed by the Assembly on Monday and awaiting Senate action -- to codify a recent court ruling protecting Black and brown immigrants from the terror of ICE arrests in and around courthouses. We must pass the HALT Solitary Confinement Act to end this torture behind bars. And we must pass Elder Parole and Fair and Timely Parole to end death-by-incarceration of Black elders.

While we mourn with those who knew and loved George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and Ahmaud Arbery, we also mourn the death of Cynthia’s brother Leonard Carter. We mourn the deaths of Kalief Browder, Layleen Polanco, Lulu Benson-Seay, Benjamin Smalls, Dante Taylor, Valerie Gaiter, Samuel Harrell, and all those who have died at the hands of racist state violence, often behind jail or prison walls. In their names, we commit to the struggle to dismantle the carceral state and build the power of our communities. We call on the New York Legislature to do the same.

***

Assemblymember Latrice Walker represents Brooklyn’s 55th District. Marvin Mayfield is a New York State Organizer at Center for Community Alternatives. Cynthia Carter-Young is a lifelong Brooklynite and the sister of Leonard Carter.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Returning Power to the People by Rebalancing the State Budget Process

Gov. Cuomo presents a budget plan (photo: Darren McGee/Governor's Office)

The job of state legislators is to craft laws that protect New Yorkers and advance equal opportunity and justice. A significant part of that job is shaping our state budget, which funds our schools, our health care, our transportation systems, and a long list of vital other public services. During a global pandemic, this already crucial responsibility has reached a new level of importance. But, over the years, in the strange world of Albany, the role and power of the New York Legislature during the budget process has been stripped away.

It’s time to re-balance the power between the Legislative and Executive branches of state government, and take back the people’s seat at the table, by amending the State Constitution and passing the Budget Equity Act.

Government works best when the checks and balances inherent to our democratic process remain unobstructed, we honor the bulwarks of our democracy, and empower co-equal branches of government. This is true at the federal level, and also at the state and local levels.

Our democracy was built on the idea that no person or branch of government should accrue too much power. But this democratic principle is not upheld in New York State. This is because a long line of governors have increasingly used a state constitutional provision from 1927 to minimize the role of legislators and grow their own centralized power in the budget process. In addition to seizing dominant control over how to fund or cut critical services, they have used their power to further their own policy agendas by putting consequential legislation directly into the state budget.

When the executive branch puts policy directly into the budget, the language cannot be amended by the Legislature. Unless the governor chooses to change their own budget bill, the Legislature’s only option is to go along with what the governor demands or reject the budget entirely. There is no debate, no room for change, no room for anyone else’s opinions – most importantly the public’s. And for years now, governors have been pushing the bounds of their executive power far beyond the purely budgetary matters for which it was intended.

This end-run around the legislative process has been used to create laws without allowing for the open and public process that new policies deserve. For example, just this year, policies like whether nursing homes should be shielded from liability if they are negligent in their treatment of COVID-19 patients (which we both opposed) and expanding New York’s prevailing wage laws to include publicly-subsidized construction (which we both supported), have become law via this undemocratic process. There was no opportunity for debate or modification without rejecting the entire state budget. A difficult vote we were forced to take.

Surely our system can’t be so far from what our founders spelled out. But unfortunately, this is what our state constitution says, as interpreted by the courts.

As legislators, we are elected to represent our constituents, but their voices are silenced when we are not allowed to fully exercise our rightful role in making laws. Our founders recognized that the process of vigorous debate and discussion, with the full engagement of legislators from very disparate communities to be able to perfect the budget into the best possible piece of legislation, was the best way to ensure that all voices and viewpoints are considered before an idea becomes law.

No matter how you feel about nursing home liability or prevailing wage policies, we can all agree that they deserve as full a public airing, consideration, and opportunity for amendment as other laws. Indeed, preserving each legislator’s role in addressing bills like those is not only critical for ensuring the best process for public involvement, it is also vital for the electoral accountability on which our democracy is founded.

Our proposed amendment to the New York State Constitution would correct this imbalance of power. It simply requires that the Governor clearly indicate any non-budgetary policy changes contained within their proposed budget, and ensure that the Legislature has the authority to amend those policy changes through the normal amendment process.

We live in a time when more and more of the residents we serve feel disenfranchised by their government and worry about the concentration of power in the hands of fewer and fewer individuals. By passing the Budget Equity Act – which then would be voted on in a statewide referendum – we can give the people the more representative government they are rightfully owed.

***

State Senator Alessandra Biaggi represents parts of the Bronx and Westchester. Assemblymember Richard Gottfried represents parts of Manhattan. On Twitter @SenatorBiaggi & @DickGottfried.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Pandemic Further Exposed Nursing Homes; New York Needs to Invest in Better Options for Senior and Disabled Populations

The coronavirus crisis put a spotlight on nursing homes (photo: Ed Reed/mayor's office)

COVID-19 has forced us to face a long-known, but ignored, truth: nursing homes are not desirable places to age. And the racial disparities in quality of health care at these facilities was only exacerbated by the pandemic, as we saw higher COVID-19 death rates in facilities with more people of color.

Just within the past month, 743 people have died in New York State of COVID, and 225 of those people were in nursing homes – a staggering 30% of total deaths. The total doesn’t even count people who were shifted from a nursing home to a hospital then died.

Governor Cuomo recently doubled down on his position that being at a nursing home was safer than having a personal aide caring for you at home. But senior and disabled residents who rely on consumer directed personal assistance (CDPA), a program that lets them hire their own caregivers so they can continue to live independently, would disagree.

A survey of consumers using CDPA, conducted by Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Association of New York State (CDPAANYS) during the COVID-19 pandemic, showed that chief among the concerns expressed by consumers statewide was a fear of being institutionalized.

Without CDPA contributing to shrinking nursing home populations, the tragedy that has played out over the last several months and continues today would have been even worse. Despite this, over $200 million in state budget cuts to CDPA over two years, including a $45 million cut at the height of the outbreak in April to the wages of these personal assistants providing at-home care, have threatened the ability of the program to be effective at a time when it’s needed most.

This $45 million represents a 25% cut to wages and benefits for frontline workers, decided on by the governor’s Medicaid Redesign Team earlier this year, despite a study showing low wages were one of the chief obstacles to both recruitment and retention of homecare workers.

As our population has aged, CDPA has played an increased role in the long-term care system for a host of reasons. Nursing homes have never been desirable, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has forced states to utilize more community-based options. Accessibility to CDPA has been a key factor in individuals who need home care being able to remain independent and stay within their communities and homes, and during the COVID crisis it may very well have saved some of their lives.

CDPA has grown rapidly as a more popular alternative to traditional forms of home care in which an agency sends workers to your home based on availability. CDPA is more flexible, letting people set their own care schedules, and because the program allows people to recruit and hire their own workers, it’s also proven exceptional at narrowing the language and cultural gaps that plague our health-care system.

Because those caregivers hired can also be friends or family, it has created options for those who do not have the luxury of being an “informal,” or unpaid, support for their family due to their economic reality. In the communities hit hardest by COVID-19 and broader health disparities, informal care often means sacrificing a paycheck.

Over the past five years the number of people using CDPA has more than doubled to about 80,000. Over the same five-year period, New York closed over 1,800 nursing home beds.

Additionally, as the epicenter of the national shortage in home care workers, New York does not have enough home care workers to handle the increased demands of our rapidly aging population, increasingly composed of immigrants and people of color living in poverty.

Regardless, Governor Cuomo and the Legislature cut funding for CDPA by that $200-plus million in just the past two years alone.

With so many nursing home deaths within our state, New Yorkers will be further spurred to look for alternatives to care for their senior family members who need it. Unfortunately, our state's response, the past few years, has been to cut long-term care services for those most in need. This position was wrong before the crisis and is still wrong for our seniors and disabled populations who wish to stay in their communities. We should instead be investing more into effective, community-based health services like CDPA to address health disparities and improve outcomes.

Our leaders must resist harmful cuts and instead enact popular proposals like raising taxes on the wealthy to bring in revenue that can be used for essential services.

CDPA’s growth has allowed the state to reduce the already devastating impact that health disparities and confinement to nursing homes are producing. That growth, while it may not have been planned, is not unreasonable given the relative increase of the aging population, the closure of almost 2,000 nursing home beds, and the shortages of traditional home care staff. For all its horrors, COVID-19 presents us an opportunity to right historical wrongs. Shame on us if we choose not to take it.

***

Bryan O’Malley is Executive Director of the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Association of New York State.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How New York Must Respond to New Covid-Related Challenges as Communities of Color Face Deadly Summer Heat

A heat wave is here (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Heat kills. It is the deadliest form of weather. And it kills Black and brown people at a higher rate than whites.

This should no longer be news. The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically exposed the many brutal inequities in our society, which have been overlooked and outright ignored by decision-makers for far too long. In the United States, generations of Black and brown people have had to endure systematic and institutional racism that has resulted in disproportionately high incidences of COVID-19 cases and mortality rates.

And with the intense summer heat having arrived, we are even more concerned because the hardships that increase COVID-19 susceptibility are the same hardships that increase heat-illness susceptibility — and in the same communities. More people are staying home, have compromised immune systems, and need safe spaces to get cool.

Annually, there are around 100 heat-related deaths, and over 400 hospitalizations and emergency room visits from extreme heat exposure in New York City. This rate will increase as summers become hotter due to the climate crisis. And, the impact is not equal. The New York City Department of Health found that neighborhoods such as East and Central Harlem, which are predominantly Black and Latino, have higher vulnerability to heat-related illness or death.

The disproportionate impacts of extreme heat are not new, nor are the solutions – such as decreasing fossil fuel emissions, designing our cities to adapt to extreme heat, and providing people with adequate cooling. However, due to the pandemic, the health threats of extreme heat are raising additional challenges that must be addressed to avoid an even deadlier summer.

Action must be taken immediately.

First, we must consider the increased importance of having adequate cooling in our homes. This summer, more people will be spending more time at home. Low-income families and families of color are more likely to be unable to access and/or afford adequate cooling in their homes, and are more likely to experience health impacts such as heat stroke, heat exhaustion, and exacerbated existing chronic conditions.

Over 85 percent of heat-stroke deaths occurred in homes without a working air conditioner, or with an air conditioner that was not used. Considering that New Yorkers typically pay 20 to 30 percent more for utilities during the summer, and within that black renters typically pay more for energy than white renters, it is especially important that low-income households have access to free air conditioners and receive significant utility bill subsidies. Mayor de Blasio’s new and ongoing program to install thousands of free air conditioners in the homes of low-income seniors is welcome, and should be quickly expanded to other households.

Second, New York City and New York State policymakers and public health workers must consider how health-care utilization will be impacted due to heat. People that may normally seek care for heat exposure may avoid health-care spaces this year for fear of contracting COVID-19. Clear, multilingual health communications in the most at-risk neighborhoods is vital for ensuring people access emergency care for heat illnesses.

Third, New York City and New York State must consider the sociocultural and psychological impacts of extreme heat in a COVID-19 summer. Culturally, many communities of color rely on one another for support. On a hot day if you don’t have air conditioning in your home, you may go to your aunt’s or your brother’s house to find a cool room. This summer, households that would have relied on one another are left with either risking their health to find social, emotional, and material support, or not have that support at all.

It isn’t enough to offer spaces to cool down that happen to be in hardest hit neighborhoods, we must partner with communities to find safe and healthy spaces for gathering that are culturally significant and will therefore be more utilized.

Finally, decision-makers must consider how anti-Blackness and white supremacy compounds extreme heat issues. As the city began to re-open, there were reports of increased policing in Black communities, disguised as COVID-19 safety measures. For example, the disproportionate levels of policing at green spaces in Black and brown communities has left many of these community members fearful of visiting parks, or simply going outside while wearing masks. Utilizing outdoor space is a key piece of keeping safe from extreme heat. If their home lacks adequate cooling, and going outdoors is unsafe, where do our community members go for respite from the heat? When needing to increase COVID-19 safety enforcement, it is important to keep the NYPD far from the job and instead increase the number of Social Distancing Ambassadors trained by the city, who can feel more like peers than violent enforcers.

We have had some wins to protect people this summer, but much more needs to be done. Due to advocacy work, the New York State Public Service Commission voted this month to approve electricity bill rebates for low-income households. And the New York City Mayor’s Office implemented the aforementioned GetCool NYC, with free air conditioners to thousands of qualified vulnerable seniors across the city (though not all who need them are getting them in time for this summer’s heat). We have worked tirelessly for this progress, but there is much more to be done to protect overburdened communities now and in the long-term.

The solution to extreme heat impacts lies in a comprehensive response informed by the communities most impacted by COVID-19 and historical racism. Extreme heat must be treated as a public health problem, not just a climate change problem.

As a precursor to what we are calling the “Heat, Health, and Equity Initiative” to be launched in 2021, WE ACT for Environmental Justice has put forth a set of tangible policy solutions on the state and city levels that will address some of the issues that have contributed to the disparate impact of extreme heat exposure and heat illness on communities of color.

Expanding LIHEAP, the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, to fund retrofitting buildings, supporting bills to ensure data collection and publication related to heat is timely, setting minimum temperature for office buildings, installing shade covering on pedestrian streets, upgrading cooling center HVAC systems, and expanding community solar are among some of the many policy recommendations WE ACT has set forth to achieve both short- and long-term solutions for extreme heat.

As we take the time to safely reopen our city, this is an opportunity to find solutions that will not only protect our most impacted communities now, but that can also address environmental racism and help us prepare for future pandemics and disasters.

***

Sonal Jessel, MPH, is a Policy and Advocacy Coordinator at WE ACT for Environmental Justice, where she specializes in addressing the health impacts of extreme heat in low-income communities and communities of color. On Twitter @weact4ej.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

An Inclusive Recovery Starts With An Inclusive Process

Gather stakeholders around the table (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

Major financial decisions in New York, such as city and state budgets and economic development deals, are typically made behind closed doors in processes that are opaque to the public and rushed through our legislatures. The recent budget deal between Mayor Bill de Blasio and the New York City Council was no different — addressing a $9 billion shortfall with contingencies and fuzzy math. It included an insufficient plan to restart our economy and will ultimately prove to be shortsighted, as we approach a fiscal crisis that will affect us for years.

We cannot meet this generational economic challenge by using the same old standard operating procedures and backroom deals. In order to create an inclusive recovery that works for all New Yorkers, we must include input from all New Yorkers.

New York was able to recover from the 1975 fiscal crisis in part because of the empowerment of a commission that led to the creation of the New York State Emergency Financial Control Board and other safeguards that were subsequently implemented.

While both the Governor and Mayor are correctly advocating for significant help in the form of financial aid from Washington, an inclusive commission of experts should be in place to implement a strategy for using that aid and back-up plans if it doesn't arrive.

The commission should include labor leaders of both public and private sector unions, whose organizations represent approximately 22% of New York City’s total workforce and provide a foundation for a prosperous middle class. Our small business community should be represented, in particular the hospitality industry that was hit so hard by the COVID-19 crisis. Voices that are too often left out of the process, such as leaders from immigrant and Black communities, tenant leaders, and others must play a central role in identifying areas of need, and the most direct means to assist New York families in crisis.

As the former Finance Chair of the New York City Council, I know that there is no substitute for expertise. Elected officials and government experts on budget and finance, including our current and former city Comptrollers, should also be important and necessary parts of this commission.

An inclusive recovery must include new sources of revenue so that we don’t have to balance our budget on cuts alone. I strongly support the full legalization of marijuana, with the revenue generated from new taxes split between New York State and the local municipalities where the sales originate. I also believe it is time to legalize the multibillion-dollar industry of sports wagering in New York in a manner that is competitive with our neighboring states. These simple policy changes will create important sustainable jobs for the 21st century.

An inclusive commission would be instrumental in ensuring that these are union jobs wherever possible, and that jobs and new tax revenue directly benefit individuals from our most vulnerable communities.

While the specific structure and role of a commission could be up for debate, there is no denying that our city will come back stronger if we include more voices in an open, honest decision-making process.

***

David Weprin is a member of the New York State Assembly and candidate for New York City Comptroller. On Twitter @DavidWeprin.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.