Mayoral Candidates Flunk First Budget Test

Budget work (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography)

Of the endless forums that are being held in the mayoral primary race, the only one that has specifically focused on the City’s fiscal situation and budget was the one last week held by the Citizens Budget Commission, my former organization. (You can watch it here, or read Gotham Gazette’s detailed summary here.)

The event, with candidates appearing one by one, revealed a range of reactions to the fiscal challenge one of them will likely find him/herself tasked with solving when they take office in January. Some candidates seem not to understand the problem, others don’t take it seriously, and still others may understand it but don’t want to really talk about it.

One can only hope that the main question CBC President Andrew Rein posed to each of the eight candidates will cause them to think in greater detail about how they will deal with the budget if elected. He asked:

If you take office next January, you will have about three weeks to submit a preliminary budget for fiscal year 2022-23 to the City Council. With a deficit now projected at $5 billion that could well grow, how will you balance the budget? What combination of spending cuts and revenue increases will you propose?

Maya Wiley made what turned out to be a standard, generic claim that there is lots of waste to be eliminated and said that she would ask agencies for cuts of 3% and work with labor to achieve personnel cost savings. But instead of balancing the budget she chose to talk about her plan to invest an additional $2 billion in capital spending to create 100,000 jobs, as if that would make the rest of the $5 billion deficit go away.

Kathryn Garcia also cited agency savings as a major way to reduce the deficit and said she would ask for agency reductions of 3-5% but could see cutting as much as 10% from some agencies, for example, by combining redundant IT services. But she decried the cuts Mayor de Blasio imposed on the Department of Sanitation, which she led until resigning last year to run to replace him, such as the termination of curbside residential compost collection. This was in fact a wise decision by the mayor, since the program has been little used and extremely expensive. If programs that are not cost effective cannot be closed (or at least postponed) what will Garcia do as mayor when her agency heads protest cuts of programs they care about? Every program has a constituency.

Andrew Yang seemed to understand the magnitude and urgency of the deficit challenge but he offered more of a mélange of various long-shot ideas than an organized plan. He spoke about the need to reduce headcount through attrition. He also offered some long-time CBC recommendations such as requiring employee contributions to health care benefits, and getting nonprofits to pay real estate taxes on some of the property they own. Does he really have plans to implement these or will he back track on them when they are met with opposition? Can he show how they total $5 billion?

Meanwhile, Yang also acknowledged that his plan to provide families with cash payments will be expensive; he said philanthropy would partner with the city to finance half the initially $1 billion program (unlikely; the last time private philanthropy gave as much as $500 million to one initiative in New York City was just after September 11, 2001) and indicated that somehow calling the payments “borough bucks” and getting recipients to spend in local small businesses would offset some of the cost.

Yang said that reform of the property tax system is sorely needed and that while it would not help with city finances short-term, it would unlock value in the billions over the long-term. If the system were truly reformed to reduce the misallocation of value between and within property classes, it would surely be more fair and rational, which might, over the long-term have a positive effect on overall development, but the damage to real estate value due to covid could take years to overcome.

Dianne Morales made it clear that balancing the budget is not a topic that influences her thinking. She didn’t address Rein’s question but instead decried the concept of austerity (though neither Rein nor anyone else used that word), said she would cut the budgets of the police, correction, and perhaps children’s services departments but would re-invest the savings in other city jobs and community investment. Like several candidates, she generally criticized the number and size of city consulting contracts. She supports several state tax increases and a land value tax, but gave no numbers for any of her proposals, on the spending or revenue side.

Eric Adams had some concrete proposals and figures. He called for personnel attrition, which he estimates would save $1.5 billion a year after a two-year hiring freeze, and would also require agency savings of 3-5%. Once again, contract spending was cited as an opportunity for savings; he would appoint a contract efficiency czar. Neither Adams, nor any of the others who called for savings in the contracting process, gave an estimate of how much money this would save. He also wants to control police overtime, which is a perennial in mayoral budget proposals but never achieved.

There is no way Adams’ savings plans would add up to $5 billion so he has tax proposals, i.e. a two-year temporary surcharge on incomes of $5 million or more and a tax on social media data collection. If the $1-2 billion these would raise a year is used to fund operating costs including his plan to open public schools year-round, there is clearly the possibility that the surcharge would not be temporary.

Ray McGuire had a theme that sidestepped the deficit-closing question from the opposite end of the spectrum from Morales. He said we cannot cut and/or tax our way out of the financial predicament. He says we must grow our way out by incentivizing and helping economic growth through spending proposals, i.e. wage subsidies for small businesses and suspension of sales taxes as well as free license renewals. He did, at least, have an estimate for the cost of the subsidies, which, at $900 million over two years, might be on the low side. He also referred to the need for personnel attrition, pension reforms, 5% agency savings, and collaboration on savings with labor. There is no question that the city needs to grow its way to fiscal health over the long run, but that will depend on the extent to which the economy bounces back after the pandemic and on many factors outside the control of municipal government. And no matter how robust the recovery it won’t enable the mayor to present a balanced budget in January 2022.

For a public official who has been directly involved with city finances for years, Scott Stringer was vague about how he would balance the budget – no doubt purposely so. He asserted that his experience as comptroller makes him the best positioned to take the needed actions, but was short on specifics, repeating calls for contract savings and curbing waste in city agencies, citing the Department of Education in particular. But he didn’t estimate how much his proposals would save. Unlike others who called for reducing personnel through attrition, he said he thinks the current city headcount (20,000 more than when de Blasio took office) is appropriate but he is also in favor of early retirement incentives that would drive up pension costs and, if the retirees are replaced to keep up headcount, would not save much in the short-term.

Finally Shaun Donovan had many specific fiscal ideas, but most had no concrete dollar values attached. Moreover, he seems to misunderstand or miscalculate some of the topics he discussed. He made a point of strongly opposing layoffs or borrowing for operating expenses but the mayor has dropped these from his budget plans. Like Andrew Yang and Eric Adams, he called for property tax reform but did not claim it would generate revenue; he is in favor of a pied-a-terre tax and a high-income surcharge. And like all the candidates he is for agency savings, contract efficiency, and working with labor to achieve productivity savings. He also suggested a CBC favorite: consolidating public employee union benefit funds.

Donovan presented value capture as a key revenue-raiser. He spoke of congestion pricing, not seeming to realize that the money from this, once implemented, is already built into the MTA’s capital budget and is not controlled by the mayor. He cited the financing of Hudson Yards as an example of a way to generate more revenue, seemingly not recognizing that it took six years for the area to generate enough revenue to pay its own debt service. More projects that ‘capture value’ to finance development will divert, not generate, revenue for the city. If he has specific value capture projects in mind to add to the city’s coffers he did not offer them.

He was perhaps most misguided in his firm belief that there will be multi-year federal aid to cover city deficits. It is a hard-fought battle for the president and Congress to get immediate state and local aid in the pending covid relief bill; further support certainly cannot and should not be relied upon as a way to sustainably balance the city’s budget.

All of the candidates have been participating in forums covering an array of topics, from homelessness and housing to criminal justice and climate change, promising all kinds of new, expansive and expensive programs. Voters should be concerned about how realistic these campaign promises really are and which of the candidates understand the difference between aspiration and governing. More probing questions about fiscal management, by the media and the public, are needed.

***

Carol Kellermann was president of Citizens Budget Commission from 2008 through 2018.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Latinos and the 2021 New York City Council Elections

Dominican Day Parade (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

In the coming months, leading up to the all-important June New York City primary elections, I will be writing a series of columns for Gotham Gazette exploring how the Latino vote can impact City Council races across the city. The series — Latino Vote ‘21 — will also highlight some opportunities that may increase Latino political representation and will at times touch on citywide or boroughwide races.

This series is, I believe, the first of its kind in a publication like Gotham Gazette. Past analytical pieces that have explored the Latino vote and Latino political representation, like those by the late Angelo Falcón, were published primarily in academic journals or for think tank-like entities like Falcon’s own National Institute for Latino Policy. I’m grateful for the opportunity to shed light on a pivotal ethnic group that could further shift the dynamics of our city’s politics.

The rise in the Latino voting population in New York City has long been explored, including by me at Gotham Gazette. Yet it is worth repeating here that Latinos are now the largest ethnic voting group in the city among all active registered voters, and among Democratic voters, they represent the second largest ethnic voting group in the city, ahead of white voters and just 80,000 behind African-Americans.

The one difference between Latinos and these two other largest racial groups is that Latinos have so far not been avid voters. But they could be. If they were, they could affect the course of New York City electoral politics quite significantly. And in fact, we have seen glimpses of hope for Latinos in the last two primary election cycles. According to voter data company L2, the 2018 and 2020 primary elections in New York each drew over 100,000 Latinos to the polls.

If these Latino voting patterns continue, Latinos could finally represent a quarter of the entire Democratic electorate in June. In turn this will determine who occupies the West Wing of City Hall, and the East Wing, where City Council Members do their business.

In the weeks to come, this series will take a borough-by-borough approach. It will look at specific City Council races in Latino-majority districts, and districts with a sizable enough number of Latino voters to affect the outcome of such races. The articles will be filled with demographic analysis, and information on candidates and stakeholders in the districts. That analysis and information will, I hope, help readers make informed voting decisions, and draw attention to important matters that may affect your life and those of your neighbors.

The implications of the 2021 New York City elections -- which will for the first time include ranked-choice voting in party primaries and special elections -- could have pivotal implications for our future as Latinos in the city. Anyone running for city office will need to listen to increasingly vocal and informed Latinos if they wish to pass by the store-front taquerias, cuchifritos, and barberias of our streets on their way to City Hall.

***

Eli Valentin is an adjunct lecturer at Union Theological Seminary, a frequent guest political analyst at Univision NY, and author of the forthcoming, Reinhold Niebuhr: A Political Life. On Twitter @elivalentinNYPA.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Needs a City Plan! ‘Planning Together’ Misses the Mark

New Yorkers participating (photo: Benjamin Kanter/Mayoral Photo Office)

On February 23, public hearings began for City Council Speaker Corey Johnson’s “Planning Together” legislation, which would institute a process for creating a comprehensive plan for New York City. I fully support city planning, but believe Planning Together’s top-down approach needs fundamental change.

New York City is virtually the only major city in this country that does not have a comprehensive city plan. Instead, we rely on a piecemeal approach to zoning that has resulted in an explosion of luxury towers without anywhere near adequate gains in real affordable housing.

Our siloed zoning approach has allowed inequity to flourish. Black and brown neighborhoods have shouldered the lion's share of new real estate development, which has led to rampant gentrification and displacement.

Arguably, the most urgent reason to adopt a city plan is the climate crisis. Considering that by the year 2100 daily high tides will flood many coastal neighborhoods, it’s hard to imagine that we can combat the climate crisis without a comprehensive plan.

For these reasons and more, it’s clear we need a city plan, yet Planning Together has several fundamental flaws. The most urgent flaw of this legislation is its top-down approach — it misses the opportunity to give the people more power in determining a just and equitable future.

In the first year of each 10-year planning cycle, every community board submits a district needs statement. In the second year, the city creates a “conditions of the city” report based on 13 categories. The categories of assessment will please many planners and organizers, as it includes a “displacement risk index” and a “segregation assessment.”

City leaders who point to these first two years as evidence of community buy-in are missing one crucial point — there is no formal requirement in the legislation to act on the information gathered from the first two years. We don’t just need more information, we need action. Without requiring interventions, it’s easy to see how real estate interests could corrupt the process.

In the third year of the planning cycle, the Office of Long Term Planning and Sustainability (OLTPS) would create three plans per district and present them to community boards and borough presidents. Let that sink in: Planning Together places the responsibility of community planning with an unelected mayoral agency instead of with the communities themselves. Community members are closest to both the unique problems and the most viable solutions in any given neighborhood. Any comprehensive planning legislation should recognize this and take a true bottom-up approach.

There are several changes to the legislation and related issues that should be made to ensure communities can fully engage in planning:

First, fully fund community boards. Currently, the combined budget of all community boards is a meager .02% of the total city budget. This lack of funding poses a major impediment to boards that may otherwise consider engaging in community planning.

Second, adequately staff community boards. Volunteer board members with full-time jobs and/or household duties cannot be expected to create a community plan. All boards should be appropriately staffed and include full-time urban planners.

Third, ensure community plans that are created have teeth and get implemented. Section 197a of the city charter allows community boards to create plans to guide development in their district. Yet, under our current system, community planning is often an exercise in futility; boards sometimes take years to compose a plan only for the city to ignore or reject it. Even when a plan is approved, implementation is not guaranteed. We cannot allow a mayoral agency to override community plans when they are created.

In Planning Together, after the OLTPS creates land use scenarios, community boards and borough presidents vote on which plan they like best. Unfortunately, these votes are in an advisory capacity. The city can move forward with whichever plan it chooses, regardless of the community decision. This (im)balance of power needs to be radically shifted to give communities the central voice in the process.

After the community board and borough president response, the City Council deliberates. Yet the balance of power between the legislative and executive branches is skewed as well. The legislation states: “if the Council failed to adopt a preferred scenario, OLTPS would choose a scenario and describe how such selection was made.” City Council members are much closer to communities than the OLTPS, so transferring power from the legislative branch to an executive agency takes away essential accountability.

Throughout the 10-year cycle, Planning Together lacks a comprehensive framework around public engagement. Our current system is entirely insufficient in ensuring community voices are heard. Case in point: the public hearing for Planning Together itself.

The meeting started at 10 a.m. on a Tuesday, when many New Yorkers were working. City officials were placed at the top of the agenda, and it took nearly five hours before testimony from other New Yorkers began. By the time public testimony began, many government officials had left the meeting. To make a comment, you had to sign up in advance, creating another barrier to entry for many citizens. Testimony was kept to a strict two-minute time frame. These factors prevented the opportunity for real dialogue

City planning is essential, and it is clear we cannot continue our current approach. Yet if we are truly to build the just and equitable city that works for all, New Yorkers need the central voice. Involving New Yorkers without becoming paralyzed by not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) forces is not an easy balance to strike. Yet, we cannot allow our fear of NIMBYism to justify a top-down approach. I urge the City Council to radically amend this plan to ensure greater community control.

***

Aleda Gagarin is a City Council candidate for District 29 in Queens, which covers Forest Hills, Kew Gardens, Rego Park and Richmond Hill, with a Master’s in Urban Planning from CUNY-Hunter College. On Twitter @AledaGagarin.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Safely Getting Signatures in a Pandemic?

Volunteers petitioning (photo: @INDBrooklyn)

Today — Tuesday, March 2, 2021 — thousands of people are taking to the streets across the five boroughs. Armed with facemasks, gloves, hand sanitizer, more pens than you can imagine, and stacks of inconveniently-long papers, these determined New Yorkers have made the decision to participate in our democratic system by collecting petition signatures to help get candidates on the ballot.

Many of them, however, did not make this decision of their own volition. Instead, they were given an ultimatum by our governor, our legislature, and our judicial system: have unnecessary, person-to-person interactions during a pandemic, or you/your candidate can’t run for office.

Disappointed does not begin to capture how the three of us and over 350 New York candidates are feeling. We are scared, and deeply concerned. After a year of failing to plan, months of public consternation, and a dismissal by a state judge, candidates, their staffs and volunteers are now forced to put their health, and the health of prospective constituents, at risk all in the name of an archaic, outdated process.

Even amidst the state’s vaccination effort — which does not currently make candidates and their campaign staff and volunteers eligible — New York continues to report nearly 10,000 new cases a day statewide, and there have been more than 47,000 deaths from this disease in our state. Still, even vaccination is not a cure-all; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cautions that vaccinated individuals can contribute to the spread of COVID-19.

New York has been in a state of emergency since January of 2020, which means our state elected officials and party leaders had over a year to figure out a safe way to petition and determine which candidates make the ballot. Instead our government failed us with their inaction and people are going to be forced into tens of thousands of unnecessary interpersonal interactions.

Governor Cuomo, who has repeatedly put politics before the health and safety of New Yorkers, has state-of-emergency authority that would allow him to waive the 2021 designating petition signature requirements. No one questioned his executive order last year that immediately suspended petitioning and lowered the thresholds, and yet with ample time to better prepare this year, the bare minimum was done.

The Legislature also failed to adequately step in, and instead let proposals languish for months, only to end up passing legislation that does absolutely nothing to protect petitioners. The bill signed by the Governor lowering the total signature requirements is not enough. Exposure is exposure, and we now have several new, highly-contagious variants of COVID-19. Reducing the amount of time New Yorkers have to petition does not help either, we are now cramming together during that shorter time period to collect signatures. While the state of our economy is a valid concern and may warrant the opening of certain businesses, petitioning has zero economic purpose. We are talking about a some-risk, no-reward endeavor.

Another bill that passed extends County Committee terms for one year, but does not address other volunteer, largely uncontested political party seats, like District Leader or Judicial Delegate. Most importantly, the bill's main flaw is that it essentially creates a county-by-county “opt-in” solution that must be voted on by each county committee.

Other bills were introduced (and even passed) in the Legislature, but either fall far short of truly protecting petitioners, or were left to languish: A bill that prevents anyone from the opportunity to ballot petition is helpful, but extremely limited in who will benefit from it. More so, under this bill, the uncontested candidate would still have to go out and petition.

A bill that would allow for electronic petitioning, which is the strongest proposal in the Legislature, is still sitting in the Senate and Assembly elections committees, even though it was introduced on January 6. Had this bill been passed immediately, the Board of Elections may have stood a chance of implementing an online petitioning infrastructure. We know it’s possible — both New Jersey and Rhode Island recently announced the implementation of online designating petitions to reduce the likelihood of campaigns becoming superspreader events.

Right here in New York, we successfully implemented online solutions for legal processes, including remote witnessing and electronic signing by notaries, and remote Board of Elections hearings due to the dangers posed by COVID-19. But even if this bill allowing for electronic petitioning was passed within days of its introduction, two months notice may not have been enough for a body that is marred by inadequate funding, bureaucracy, and politics.

That’s why, when it became crystal clear our leaders would not go beyond a careless “we’re working on it” approach to prioritizing public health, we filed suit. But even during the hearing, we knew that the dangers of creating a superspreader event were not truly considered.

Some of the “alternatives” proposed by the judge, like setting up plastic tents along the city sidewalk to protect petitioners, are simply outrageous and not feasible. Anyone who’s petitioned knows that it is an intimate, one-on-one interaction. The petitioner must first engage someone, most often a stranger, and ask them to stop and speak, explain why they stopped them (because many people are unaware of this process), convince the person to sign for all the candidates on the petition, and witness the person sign. In large cities where you can’t canvass door-to-door to target voters, the most effective way to do this to collect the appropriate number of signatures is to stand on crowded and busy pedestrian areas.

Our electeds may have reduced the number of required signatures, but let’s look at a quick example, one that City Council Member and comptroller candidate Brad Lander shared: if a New York City Comptroller candidate needs 2,250 signatures under the new law, they’ll most likely collect three times that amount (which is standard practice for all candidates), amounting to 6,660 signatures per candidate. With seven candidates running for comptroller, that’s at least 50,000 mandated interactions. And let’s not forget: this doesn’t include candidates running for Mayor, City Council, Borough President, Manhattan District Attorney, District leader, or Judicial Delegate. Council Member Lander’s example was for only New York City, but we will have candidates throughout the entire state engaging in these dangerous interactions. How can we collect signatures while maintaining social distance?

The truth is we can’t. New Yorkers deserve better, and we hope the state Legislature will reflect on the danger they put hundreds of thousands of people in, while most of them do not have to lift a finger and petition until 2022. To all of our fellow candidates, campaign staffers, and volunteers: please take care of yourselves, your neighbors, and your communities. Double-up on masks, rotate and clean pens, and commit to not challenging each others’ signatures.

Despite the failures of many, let’s get through this safely.

***

Erica Vladimer, Lauren Trapanotto, and Corey Ortega are candidates for office. On Twitter @EricaForNY, @l_traps, & @mrortegany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Expanding Educational Opportunities for Our Youngest Learners

Kids at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Economic and racial inequities have been a plague in New York City’s education system for decades, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the situation for our most vulnerable students. Faced with the reckoning of remote learning, we’ve been bombarded with stories of how our public schools lack the resources to adequately equip students with the technology they need to stay afloat, while something as simple as providing wi-fi to every child has only been met with excuses. Yet often lost in these stories is how the discrepancies in access to quality early education has created this game of “catch up” the city, parents, and students now face.

In Ridgewood, Maspeth, Glendale, Middle Village, Woodhaven and Woodside -- which make up Queens’ 30th City Council District -- we see these stories playing out along geographical and racial lines every day. It’s no coincidence that the success rates on the specialized high school admission test (SHSAT) for students at schools in predominantly whiter areas of our district are 400-500% higher than at those with a higher foreign-born population. And while much attention is paid to test prep or teaching at the middle-school level, not nearly enough attention is paid to how disparities begin for our students as early as day-care.

Financially, the cost of day-care and early child education averages between $10,000-$15,000 per year. This is before you take into account that parents who cannot afford to pay exorbitant costs for day-care and education must sacrifice their own jobs and economic well-being to look after their children before they are old enough to receive a free public education. Moreover, when you consider many of these same parents may not speak English as their primary language, it’s easy to understand how we’re failing our students at their most pivotal age.

This is why it is imperative that our local legislators continue to fund and expand early childhood educational programs and raise awareness of the resources already available to our families.

Studies have shown that an investment in early childhood education is an investment in our society and public safety at large. A comprehensive review of economic analyses of pre-K concluded that for every $1 invested in early childhood programs, there is a $17 return to society, and a dramatic decrease in the incarceration rate.

Throughout the country we’re seeing more states reap the benefits of investing in early childhood education. Programs like Universal Pre-K provide a free, high-quality education for children starting at four years old, and cities like New York City and Washington D.C. have implemented programs that expand universal free education for children as young as three. Expanding these programs allows families to get an early start on their child’s educational needs, while simultaneously alleviating the financial burden of child care for every parent and opening up opportunity to earn additional income.

Additionally, Pre-K and 3-K For All in New York City offer dual language classes and special education for students who are learning English as a second language and for students with special needs, respectively. I am especially proud of these programs as I helped consult the Department of Education during their implementation.

It has not been lost on me that throughout District 30 it’s been the Polish- and Spanish-speaking populations that have been hardest hit by the pandemic. Parents have had to take on the role of educator, provider, and caregiver while being forced to navigate the educational space at a disadvantage. According to the Department of Education’s MySchools directory, there are over 80 universal pre-K school locations in District 30, but none that offer dual-language programs or secondary language support. This despite a demographic that is nearly 40% Hispanic and 50% foreign born. And while there are paid, dual-language 3-K programs that offer discounted rates for families who qualify, there are no public, city-funded 3-K programs in all of District 30.

Yet these problems offer us a way to provide incentives for not just families, but the teachers and educators who we would rely on. By expanding and reforming the bilingual certifications needed to teach younger children, we can offer scholarships and financial aid to student-teachers who can teach languages like Spanish, Chinese, and Polish at an introductory level, helping provide educational support for both our children and their instructors.

From every perspective, investing in early child-care and education is not only the right thing to do, it is the financial and morally prudent thing to do. Given the evidence, the question is not if early childhood intervention will benefit communities in the long run, but how quickly can we utilize our resources to best support the programs that equip families and children for school readiness and success. Our children deserve the opportunity to thrive and investing in early childhood education is how we ensure they can do so.

I will continue fighting to ensure that every family has access to early childhood education, expand educational programs in every neighborhood so no child falls behind, and offer resources tailored to the needs of our students.

***

Juan Ardila is a Democratic candidate in the 30th City Council District, a resident of Maspeth, and the first Latino to ever run for the seat. On Twitter @JuanArdilaNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

With More Than 1 Million Uninsured, New York Needs Immediate Comprehensive Health-Care for All

Health care push (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

The pandemic has been raging throughout New York for nearly a year, killing tens of thousands of our neighbors and dramatically altering every New Yorker’s life. None of us have been untouched by this deadly virus.

Throughout this year, the critical need for access to health care has become more clear than ever. So too have the gaping inequities across our state. And, while Governor Cuomo has claimed to make confronting the pandemic his number one priority, he has cut Medicaid and other vital health services. This includes reducing or eliminating certain public health programs, specifically, reducing the reimbursement rate for general public health work to 10% in the fiscal year 2022 budget. In the current year’s budget (fiscal 2021), this matching funding for New York City was cut from 36% to 20%, which resulted in a cut of $65 million to vital public programs and services in the city. These services include family health, communicable disease control, chronic disease prevention, community health assessment, emergency preparedness, and environmental health.

Furthermore, there continues to be a Medicaid global cap that imposes automatic cuts when Medicaid spending hits a predetermined threshold. Last year, Medicaid had across-the-board cuts of 1.5%, and this year New York plans to again implement cuts of 1%.

Under Cuomo’s leadership, the state has not taken the needed measures to make affordable, high-quality health care coverage available to every New Yorker, regardless of immigration status. It’s time the State Legislature takes action to change that.

Lourdes Narvaez is a 24-year-old immigrant from Ecuador. Early in the pandemic, like many other thousands of community members in Jackson Heights, Queens, Lourdes contracted COVID-19. At the time, she did not dare go to a hospital or a clinic to receive medical attention for fear of a more severe contagion. Even if she had wanted to, the hospitals were overcapacity. And, as someone who doesn’t qualify for health insurance because of her immigration status, she didn’t have a doctor to call to discuss her health or how to treat the coronavirus. She was very afraid of the virus, but she was also afraid of seeking care and later being burdened with medical debt.

Lourdes is one of 1.1 million New Yorkers who do not have health insurance, and one of 240,000 low-income people with income below 200% of the federal poverty level who specifically lack insurance because of their immigration status. New York can and must take action to ensure that every New Yorker, regardless of immigration status or anything else, has access to health insurance and the coverage we need.

Members of both the New York State Assembly and Senate have gathered for a health-focused hearing and the solutions are clear.

First, the New York Health Act (NYHA) would ensure comprehensive coverage for every New Yorker. All New Yorkers, regardless of immigration status, would be covered for primary, preventive, and specialty care; hospitalizations; mental health; reproductive health; dental, vision; and more. They would also be able to choose their medical providers, instead of being restricted by insurance companies. The NYHA would pay for all covered services, ensuring individuals can access care without unaffordable copays, deductibles, or premiums.

As we proceed toward passing the New York Health Act, New York should also take immediate action to ensure that immigrants like Lourdes have access to health care. We must in the upcoming budget due by April 1 allocate $13 million to create a temporary state-funded Essential Plan for all New Yorkers with income up to 200% of the federal poverty level, who have had COVID-19, and who are excluded from coverage because of their immigration status. New York should also dedicate a portion of new revenue to make all low-income undocumented New Yorkers eligible for a state-funded Essential Plan.

Unfortunately, instead of exploring the big, bold solutions that we need to meet the scale of this crisis, Governor Cuomo has time and again resorted to budget cuts that tear at the safety net — by cutting Medicaid, withholding payments from municipalities and community-based providers, and more. At this point, the administration has also confirmed that it knowingly withheld information on nursing home deaths, while several health department officials have left.

And in the face of loud calls across the state to tax the wealthiest New Yorkers to prevent cuts to care and instead of focusing on meeting the scale of communities’ needs, the governor has spread lies: low-balling the amount that could be raised through progressive taxation, and fear-mongering that billionaires will leave.

It’s time to stop trying to protect the rich and powerful, and instead orient New York to meet the needs of low-income and working-class New Yorkers, particularly those of color. Passing the New York Health Act — and, in the interim, creating a state-funded Essential Plan for all New Yorkers earning up to 200% of the federal poverty level — is the best way to demonstrate that commitment.

***

Jessica González-Rojas is the State Assembly Member representing New York’s 34th District in Queens. Theo Oshiro is the Deputy Director, and incoming Co-Executive Director, of Make the Road New York. On Twitter: @votejgr & @TheoOshiro.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Unable to Move De Blasio, Carranza Leaves a Still Deeply Divided School System

Mayor de Blasio and Chancellor Carranza (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

In July 2018, a few months after New York City welcomed a new schools chancellor, The Atlantic asked, “Can Richard Carranza Integrate the Most Segregated School System in the Country?”

Now we have our answer. On Friday, Carranza announced his resignation, attributing it to the emotional toll the pandemic had taken on him. But many observers believe — and The New York Times reported — that Carranza decided to leave at least partly because it had become clear that Mayor de Blasio did not share his commitment to ending segregation in the nation’s largest school system.

So with 10 months left in office, de Blasio, who ran for mayor decrying New York’s “tale of two cities,” leaves New York public schools with two systems, divided by race, class, and resources. The question is whether the battles of the last seven years — and Carranza’s tenure — will lay the groundwork for the next mayor to end that split.

Integration advocates say Carranza’s three years have not been devoid of accomplishment. They cite his overseeing integration plans in Manhattan’’s District 3 and Brooklyn’s District 15, laying the groundwork for similar efforts in other districts, instituting an at least temporary end to screened admission to middle schools, and launching an ambitious program of anti-bias training for teachers.

Above all they commend the outgoing chancellor’s unabashed advocacy for integration.

Zakiyah Ansari, advocacy director of the Alliance for Quality Education, praised Carranza as a strong leader “who’s very clear on what his agenda is and…who didn’t have any problem speaking out when white parents came after him” and when the New York Post went after him. “He has never backed down,” she said.

“Carranza used the bully pulpit to elevate the issue in a way no previous chancellor had,” Richard Kahlenberg, director of K–12 equity at the Century Foundation and a member of the executive committee for the mayor’s School Diversity Advisory Group, said by email.

But the last three years brought resistance from a supposedly progressive mayor who lacked either the conviction or the backbone to fight for true equity. “No chancellor has ever highlighted racial justice the way that Chancellor Carranza did. The big disappointment was he was dealing with an obstructionist mayor,” said Matt Gonzales, director of the Integration and Innovation Initiative at NYU Metro Center.

The angry town hall meetings and the attacks on Carranza in The Post and elsewhere also highlighted once again how strong the resistance to equity can be and made clear that many white and Asian parents believe the system, unfair though it may be, is good for their children and should remain.

“Those citizens with the most political power in the city are often defenders of the status quo, because they perceive the status quo to directly benefit their children. For many people, the practical considerations outweigh the philosophical agreement with school diversity,” Stefan Lallinger, a fellow at the Century Foundation, wrote by email last year.

School integration never appeared at the top of de Blasio’s agenda. He boasts of being a public-school parent but both his children went to academically selective elite public schools for middle school and high school (as did mine). In an early stint on a local school board in Brooklyn, de Blasio helped devise a choice system for middle schools that hardened racial and economic divisions in the area’s middle schools — a program that, owing to community action, has since been dismantled.

Tellingly his campaign rhetoric on divides in the city did not focus on K-12 education. But school integration became a kind of elephant in the room when, a few months after de Blasio’s inauguration, the Civil Rights Project at UCLA released a report finding that New York State had the most segregated schools in the country, owing largely to educational segregation in New York City, and that the system was becoming increasingly divided.

Students began speaking out loudly and eloquently about the effect segregated schools had on their education and organizing around the issue. Some politicians echoed their calls, and the City Council passed a few measures aimed at the problem while a few members made the issue a priority.

There was “a hope, if not an expectation” that de Blasio and his first schools chancellor, Carmen Fariña, would take on segregation, recalls David Bloomfield, a professor of education law at City University. But he says, “The best Carmen could come up with” was a suggestion that students have pen pals of different backgrounds and de Blasio would not even say “segregation.” Instead the mayor focused on universal pre-K and 3K, along with expanding access to advanced placement and computer sciences courses — all of which, de Blasio said, would expand opportunity for all children.

Then, in 2018, after his first choice for next schools chancellor suddenly bailed out, de Blasio appointed Carranza, the Houston school superintendent and a grandchild of Mexican immigrants. Carranza was quick to call out city schools for being deeply divided and zeroed in on schools that use grades, test scores, and other measures to admit some children — and not others — as a key driver of that segregation. “Why are we screening kids in a public-school system? That is, to me, antithetical to what I think we all want for our kids,” he said.

The move to get rid of screens was a constant of the next three years but repeatedly fell far short of Carranza’s goal.

The first round involved the test that serves as the sole basis for admission to the city’s eight academically elite Specialized High Schools. By the time Carranza arrived, de Blasio was already planning to call for junking the test in favor of a system where top students from every city middle school would be chosen. Because of a state law passed in 1971, the change required state approval — at least for the three largest and most prestigious of the schools.

It immediately ran into a buzz saw, particularly in the Asian community where many families see a high score on the admissions test as a ticket to success. De Blasio had not consulted with Asian leaders and parents beforehand, fueling sentiment that his policy was targeting Asians. Carranza reinforced that when he said, “I just don’t buy into the narrative that any one ethnic group owns admission to these schools.”

Few if any prominent politicians backed the mayor’s specialized high school admissions plan. By September 2019, de Blasio was acknowledging he had failed and that he might be open to keeping the test after all.

Lallinger of the Century Foundation said the problem with the proposal was not its substance. “The failure to enact it was entirely a political failure. There was no meaningful stakeholder engagement before it was announced, and no opportunities to tweak it to address the concerns of some constituencies before it was presented as an alternative to the status quo,” he wrote in an email last summer. The retreat on specialized schools was the first of many.

In 2019, the School Diversity Advisory Group, which the mayor named in 2017 in response to significant pressure to desegregate the city’s schools, released two sets of integration proposals. The first report, issued in February, had 67 recommendations, such as setting goals for diversity and devising a more culturally responsive curriculum. The administration embraced 62 of them.

The group’s far more sweeping report landed that summer. It looked at the system of choosing students for coveted schools and essentially called for blowing it up. Middle schools, it said, should no longer use admissions criteria such as grades, attendance, and standardized test scores. High schools should abandon lateness, attendance, and geography as criteria for admitting students and instead adopt admissions policies that would create diversity.

Perhaps most controversially the report called for a complete rethinking of the elementary school gifted and talented program, including elimination of the test that determines which children will gain the coveted seats.

The reaction was harsh and immediate. Critics charged that the proposals, if accepted, would spark middle class flight from the city. National figures weighed in with Fox television host Tucker Carlson accusing Carranza of “leading the charge” to sow “racial division in America’s largest city.”

Few New Yorkers who have seen de Blasio’s handling of tough issues, such as police reform, were surprised at what happened next. The mayor — who was running for president at the time — barely acknowledged the recommendations, didn’t meet with the group that he had appointed, and downplayed the importance of integrating schools. “All the theory about how we create a utopian world, you know how we get everything to be perfectly balanced at all, that’s not what parents are talking to me about,” he said at a press conference that September. He pledged a review of the group’s recommendations, but there’s no evidence that happened. De Blasio’s February 2020 State of the City speech did not mention school integration.

The genie, though, would not go back in the bottle.

Angry over calls to eliminate tests as an admissions criteria, a proposed integration plan in Queens, and a community school board member in Brooklyn who referred to Asians as “yellow,” activists, many of them Asian, vented their ire at Carranza. They demonstrated at his town halls, holding signs demanding he be fired, and charged that they had been barred from a March meeting at Brooklyn’s James Madison High School. De Blasio defended Carranza against charges of racism but remained largely silent on the issues.

“De Blasio allowed the equity agenda to be demonized” and be tied to Carranza, said Gonzales, who served on the School Diversity Advisory Group. “He was a brown man who spoke about racial justice and that’s what happens.”

For his part, Carranza, in announcing his resignation, seemed to acknowledge he could have done better at reaching out to various groups in the city.

On the other side, frustrated that sweeping change seemed stalled, students staged walkouts at individual schools during the first half of the school year and planned to up the ante with a citywide school walkout.

Then the pandemic hit. The shift to remote learning threw the screening metrics into disarray, as state standardized tests used for high school and middle school admissions were canceled, and the city scrapped traditional grades for grades K-8. The specialized high school test and elementary school gifted test seemed in jeopardy as some educators and politicians questioned the validity of tests when so many students’ lives were disrupted. They expressed concern about the safety of in-person testing and grumbled about spending money on them at a time when the city faced massive budget cuts.

Carranza clearly hoped to seize the moment. In April, he told the Association of Latino Superintendents and Supervisors he was “not allowing” people to talk about returning to normal because that normal was rife with inequities. “We see this as an opportunity to finally push and move and be very strategic in a very aggressive way what we know is the equity agenda for our kids,” Carranza said. “Never waste a crisis.”

Soon after came another crisis: George Floyd’s killing by police in Minneapolis. The ensuing focus on racial injustice in America reinforced arguments that screened schools were inherently unfair and even racist. Teens Take Charge stepped up its assault on screens and released city data showing that some selective high schools with large numbers of Black and Latino applicants tended to admit more of their White and Asian applicants than their Black and Latino ones.

To the frustration of many parents, the administration repeatedly delayed deciding how it would handle admissions for next school year. But when it finally began announcing its admission policies in December, some screens, including controversial ones, remained.

At least for this year, middle schools cannot use criteria such as grades and attendance to select students but will choose them by lottery. High schools can no longer give preference to students from their Community School District, ending the policy that made schools in Manhattan’s affluent District 2 disproportionately white and privileged. High schools can, however, continue to choose students using test scores, interviews, and portfolios, and many of them are doing that.

Some critics worry the confusion about new criteria and some of the changes could make the system even more unfair.

“We are frustrated that the DOE has missed an opportunity for truly transformative change by failing to remove all academic screening for high schools, even as a temporary measure. The lack of valid metrics during the pandemic, when already-existing inequities were magnified, highlights the baselessness of screening policies in general,” Parents for Responsible, Equitable, Safe Schools said in a statement.

The city also decided to keep the Specialized High School test, citing the state law.

The biggest furor came over the gifted and talented test, which had been given one-on-one by proctors to children who would enter kindergarten through third grade the following September. Many consider this the most egregious of New York’s screens, a belief bolstered by the fact that no other school system selects children for gifted programs this way. Experts argue that testing children as young as four — before most have had many influences beyond their family — tells you more about the child’s home than the child. In New York, it tells you about race: three quarters of kindergarteners in the city’s gifted programs in 2017-18 were white or Asian, even though white and Asian students accounted for only about a third of city kindergarten students.

Success on the test puts students on track for future academic success. Children in the gifted program are likely to land in a selective middle school, which is then a path to passing the Specialized High School test.

The normally toothless Panel for Educational Policy barred the city from issuing a contract for the gifted and talented test this year, but de Blasio remained adamant about finding a way to screen children. The administration decreed that, to qualify for the program, little children would have to get recommendations from their preschool programs or be interviewed.

Even supporters of screened programs balked, the absurdity of the plan seemingly evident to everyone but the mayor, who also said he would be offering a longer-term reform plan for gifted and talented later this calendar year.

“They’ve chosen the system that has been proven to be the least effective for identifying gifted students who are of color, or low-income, or English learners…Subjective evaluations have always benefited the wealthy and middle class,” Alina Adams, an education writer and school choice advocate, told the Post.

M. Rene Islas, former executive director of the National Association for Gifted Children, which advocates for gifted programs, said he was unaware of any evidence that young children could be identified as gifted in a remote interview and that allowing evaluators to Zoom into children’s homes could introduce a whole new set of biases. “I’m really worried about that,” he said, according to Chalkbeat. “I don’t think that’s going to help with equity.”

Although Carranza and de Blasio have downplayed policy differences, the mayor’s stubborn endorsement of the gifted and talented admissions was probably too much for the chancellor. The Times reported that Carranza had drafted a resignation letter after a heated conversation with de Blasio over the future of gifted and talented classes.

There are many possible reasons as to why Carranza resigned. “Maybe we should just take him at his word that he was simply exhausted and vulnerable,” Bloomfield said. With the de Blasio administration going into its final months many officials are leaving — in fact a number at the education department already have. Others look to the atmosphere in the mayor’s office and what many see as his propensity for micro-managing.

With Carranza out the door, de Blasio’s legacy on school integration will remain one of weakness, at best, and opposition at worst. He will be seen as someone who either did not believe in equity or was too timid to take on the powerful forces supporting the status quo.

When de Blasio was elected, advocates had “thought we had someone who would be a champion,” Ansari said. Instead the mayor did not back Carranza up when he was under attack and flouted the wishes of the Panel for Educational Policy when it blocked the gifted and talented test. “The mayor’s not all in on democracy, let alone equity,” she said.

Nyah Berg of New York Appleseed, which advocates for school integration, also blames de Blasio for stalling the drive for a more equitable school system. “So much could have been done and done sooner if it were not for the lame duck de Blasio administration obstructing progress for integration at every turn. It will be hard to judge Carranza’s leadership as he was never allowed to truly lead and was micromanaged by a mayor who has shown no moral courage, leadership or intent to uphold his promise in addressing his ‘Tale of Two Cities,’” she said by email.

In resigning Carranza said that, while “it’s never been my style to look at the coulda shoulda woulda,” he would have done more to engage with communities. Gonzales hopes that incoming chancellor Meisha Ross Porter’s long experience in New York City schools and status as a lifelong New Yorker will help her do that and “move things forward” during the next ten months — or beyond if the next mayor lets her stay on.

As Porter works to fully reopen the city’s schools, integration advocates will be looking to shape the debate about education in the mayoral campaign and elect someone who will take on what de Blasio didn’t.

They will also be examining the structure of mayoral control of city schools. Ansari said that issue has been “simmering” for a while but that the chancellor's resignation was “an aha moment for me”: “We could have had big change,” she said, but the mayor blocked it.

While mayoral candidates have been asked to give a thumbs up or thumbs down on mayoral control, Gonzales said the discussion must go beyond that to creating “a vision for actual democratic governance of schools in New York City.”

Whoever becomes mayor in January, the debate about how — and maybe even whether — to achieve equity in city schools will continue. Along with coming back from the pandemic, “the number one education issue” for whoever takes office in January 2022 will be “to fulfil the promise that de Blasio broke and that’s mainly increasing diversity and desegregating schools,” Bloomfield said.

Kahlenberg agrees: “The next mayor will not be able to ignore segregation, as so many had in the past. Richard Carranza is a big reason for that.”

The question though is what, if anything, will the next mayor want to do about it? And will he or she — and their schools chancellor — succeed?

As the last years have shown, it will not be easy.

***

Gail Robinson is a former editor of Gotham Gazette who writes on education and other policy issues and teaches at Baruch College. On Twitter @GailNRobinson.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

How New York City Can Truly Turn the Tide on Homelessness

Housing underway (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

We as a city spend $3 billion annually on shelters -- including renting hotel rooms -- that fail to provide the services New Yorkers experiencing homelessness need.

These band-aid solutions don’t work. They’ve never worked. Before COVID-19, more than half of New Yorkers were paying more than 30% of their income on rent, and more than 140 New York City schools had a homeless student population of over 20%. Almost 1 in every 100 New Yorkers experienced homelessness in 2019. Despite big promises, Mayor Bill de Blasio has overseen a 23% increase in homelessness during his tenure, even as homelessness declined nationally. While the mayor’s approach expanded access to dormitory-style shelters, it didn’t come close to adequately addressing the root causes of homelessness: a citywide lack of stable, affordable housing and access to “wraparound” social services and healthcare.

The homelessness crisis has only become more potentially dire due to pandemic-related job losses, particularly among lower-income households, causing more families to fall behind on rent and putting nearly 150,000 New York City households at risk of eviction. While the state eviction moratorium and federal stimulus checks have so far prevented the worst, many of the most vulnerable New Yorkers still fall through the cracks.

With so many of our neighbors at risk of losing their homes, we need a mayor who will treat homelessness like the crisis it is. It’s time for bold, transformative solutions on housing and homelessness — it’s time to move from a shelter strategy to a housing strategy. It’s time for housing that heals.

I’m a dedicated public servant who knows how to manage a crisis. But unlike this mayor, I’m not content to just manage homelessness – I pledge to end it.

It starts with smarter leadership. Right now, 19 city agencies are “responsible” for tackling homelessness, which means nobody is in charge. When I’m mayor, for the first time homeless services, housing, and economic development will all report to the same deputy mayor, who will be held accountable for treating housing issues with one comprehensive approach.

We’ll also put more resources towards prevention, focusing on the top risk factors: job loss and health crisis. New York’s CityFHEPS rental assistance program provides temporary vouchers to at-risk households, but the voucher amounts are often too low to rent an apartment. Fully funding CityFHEPS means less homelessness in the first place.

Shift from a shelter strategy to a housing strategy also means instead of paying to rent hotel rooms we purchase suitable empty commercial spaces and convert them into 10,000 permanent supportive housing units. California’s Project Homekey used federal coronavirus relief funds to acquire 6,000 vacant hotel rooms in a matter of months, and New York City should act with similar urgency.

You get what you measure. Rather than fixating on units, we will focus on reducing the number of people who are sleeping on the street, who are rent burdened, and who are in shelters. We’ll open new drop-in centers with bathrooms and critical services, creating more opportunity for social workers to build trust and a pathway to permanent housing, and proactively engage with individuals leaving the correctional system.

Finally, we’ll address homelessness at its roots by fixing our broken housing market. Despite red-hot demand, New York builds less housing per-capita than almost any major city in America. We’ve only added housing in a few neighborhoods where zoning has encouraged it, and we’ve even lost housing stock in areas including the Upper East Side, Sunset Park, and Bayside. It’s no wonder that only 4% of New York’s essential workers can afford an apartment that fits their budget. Our housing market has become a sick game of musical chairs, leaving more and more New Yorkers without a place to call home.

My administration will fund 50,000 new affordable homes for New Yorkers making under 50% of the Area Median Income (AMI), finally targeting the city’s affordable housing plan to the greatest need. We’ll plan for citywide affordable housing growth, especially in high-resource neighborhoods with good access to jobs, transit, schools, and parks. We’ll update the zoning code and streamline the byzantine permitting process, which makes it all too easy for housing opponents to block affordable housing. And we’ll implement common-sense reforms like legalizing basement units, backyard units, and small apartment buildings citywide.

We won’t be the first city to use this approach to deliver results. In 2011, Houston, suffering from record-high homelessness, adopted The Way Home, which identified homeless residents and matched them to housing within 30 days. Houston redirected funding into building permanent supportive housing and improved coordination among service providers, nonprofits, and government. Houston’s housing supply also grew quickly, holding rents flat. Six years later, homelessness had fallen 60%, and military veteran homelessness was effectively ended. This playbook works — we just have to follow it.

It’s one thing to say that housing is a human right. It’s another thing to execute on it. With COVID-19 still putting too many New Yorkers’ housing in jeopardy, our next mayor needs to embrace proven solutions and prioritize ending homelessness. New Yorkers have had enough of excuses — it’s time for experience.

***

Kathryn Garcia is a Democratic candidate for mayor of New York. On Twitter @KGforNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

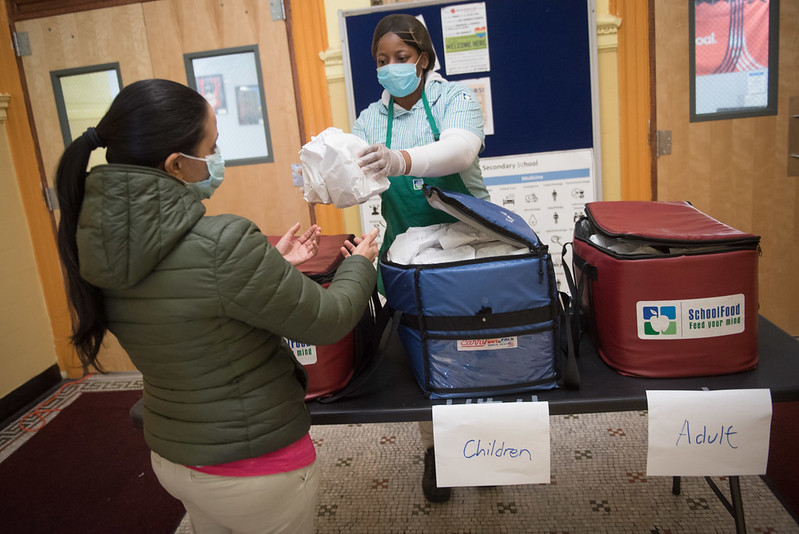

Hunger is Still Here: Nourish New York Can Help

Free meals (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

We are fast approaching the one-year mark of an incredibly tumultuous time, a year filled with hardship and uncertainty. There is neither a geographic corner of New York nor area of industry in our state that has escaped unscathed. As our economy has gone into a tailspin, food insecurity has skyrocketed. Food banks and pantries have emptied their shelves, and farms have been unable to sell their goods as supply lines have been disrupted. One of the most effective ways we have been able to address food insecurity statewide is through the immensely successful Nourish New York program.

The Nourish New York program was launched by Governor Cuomo in 2020 in order to address two separate, yet connected, issues. Due to decreased demand, disrupted and broken supply lines, and processing plant workers contracting the virus, upstate farmers were struggling to sell their products. Because wholesale consumers such as school districts and restaurants were closed, they no longer needed fresh produce, dairy and other items. At the same time, many people, some for the first time ever, were turning to food banks and pantries for assistance.

Social service providers, governmental agencies, houses of worship and non-profits, became completely overwhelmed. Food banks, which generally rely on donations, had to quickly shift funds towards purchasing food to meet demand, as the pandemic caused a decrease in institutional donors such as catering halls and restaurants, now shuttered due to pandemic.

The Nourish New York program connects regional agricultural producers with emergency food providers. New York farmers, many of whom were struggling before the pandemic hit, have been given a lifeline, as food banks receive state funds to purchase fresh produce, dairy and meat from participating farmers at market rates, and then distribute that food to those in need.

Just as Nourish New York was a timely response to immediate need, the incredible work undertaken by organizations like Met Council, City Harvest, and the Farm Bureau cannot be understated. The coordination among hundreds of organizations and their volunteers to safely and efficiently implement the Nourish program was instrumental in its success.

The program has sustained over 4,000 farms and distributed over 17 million pounds of fresh food. With nearly 1 million New Yorkers out of work, supporting the agencies and providers that help ensure vulnerable families are fed is crucial. We not only need to continue funding this program, but we must dramatically expand its reach.

Currently funded at $25 million for the next year, this number must be doubled. Nourish New York is a win for both our farmers, who have been ravaged by the pandemic, and for New Yorkers who face daily food insecurity.

In our state, food insecurity is most prevalent in households with children. According to City Harvest, the number of children going hungry in New York City alone is 466,000 -- a nearly 50% increase over the past year. Childhood food insecurity is linked to increased risk of developmental issues, lower psychosocial function, school absence, aggression, anxiety, behavior disorders, depression, substance abuse, and difficulty concentrating. As an estimated one in four children is going hungry, parents are selflessly skipping meals so they can attempt to feed them. Adult family members are forced to make perilous choices among rent, utilities, medical care, and nourishment. The broader implications of food insecurity on adults also extends beyond nutritional deficiencies, with studies showing compounding detriments to overall mental health.

The Nourish New York program is also focused on improving food access to communities of color, which have taken the economic and physical brunt of this pandemic, by greatly increasing access to healthy foods. In the past year, we have seen local farmers’ market utilization increase by over 50% in historically underserved communities. Communities with dietary restrictions have also had a particularly difficult time finding resources, and the Nourish program has been able to secure food that meets their needs. Kosher, Halal, organic, and vegetarian options have all been added to this initiative.

Rebuilding a post-pandemic economy in New York State will require bipartisan creativity and fortitude. Nourish New York has proven to be a fiscally-responsible success in addressing food insecurity, assisting our farmers and connecting upstate and downstate economies. Many federal and state programs failed our community over the last year, preventing excluded and undocumented workers from accessing life saving services, but Nourish New York made no distinction and ensured that thousands of New Yorkers had food on the table. While we have taken steps towards addressing food insecurity during these unsettling times, the economic devastation caused by this pandemic is far from over. The Nourish New York program must be a part of the long-term planning of New York State.

***

Assemblymembers Daniel Rosenthal, chair of the Assembly Task Force on Food, Farm & Nutrition Policy, and Catalina Cruz, chair of the Assembly Task Force on New Americans, represent parts of Queens. On Twitter @DanRosenthalNYC & @CatalinaCruzNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York’s Colleges and Universities are Key to Its Revival

Pace University (photo: Pace University)

We knew our city never was or would be dead. Vaccines are here, restaurants have re-opened for indoor dining, and commercial life is returning. Apartment sales, rental volumes, and prices are back on the upswing. And throughout the downturn, major, forward-thinking employers like Facebook and TikTok signed giant new office leases in Manhattan.

But we still need to do everything we can to bring in the next generations of New Yorkers. And that means recognizing what an economic engine New York’s colleges and universities are for our city and state. We attract the young, ambitious, and diverse talent our city needs to restart and rebuild.

There were nearly 1 million undergraduates enrolled in New York’s colleges and universities in the last academic year, according to statistics from the state Education Department. More students travel to New York for college than to any other state, according to data from the Commission on Independent Colleges and Universities in New York. And these students are the people who will help rebuild New York and drive our future.

At Pace University, with campuses in Lower Manhattan and Westchester, we have a proud 115-year history of helping hard-working, ambitious young people to transform their lives through the power of a college education. Our student body of 13,600 undergraduate and graduate students—many of them the first in their families to attend college—come to Pace from 47 states and 99 countries.

New York’s private colleges and universities, Pace among them, generate $89 billion in economic impact annually, and support 415,600 jobs in the state, according to CICU. The sprawling SUNY system drives another $28.6 billion, according to a study by the Rockefeller Institute for Government. In total, that’s more than $117 billion in economic activity in our state attributable to higher education—more than one-and-a-half times the $74.6 billion output of the state’s manufacturing sector (per the National Association of Manufacturers).

In Washington, the new Biden administration is committed to supporting colleges and universities. President Biden has promised to expand the Pell grant program that provides government aid for low-income Americans. That’s an important and overdue change, as the size of those grants have not kept up with inflation. He wants to make federal loans easier for students and their families to navigate and less costly, both very welcome measures. And he has said he’ll expand student loan forgiveness for students who go into public service, which will help both students and our important public sector.

The relief package passed at the end of last year included some aid for higher education, and President Biden’s American Rescue Plan, currently being debated in Congress, promises more.

But colleges and universities are in a deep financial bind right now. Tuition revenue has fallen because of the pandemic, in some cases precipitously, and expenses for student, faculty and staff health and safety, including extensive testing protocols, have increased. Strapped state budgets aren’t able to fill the gap, and tuition increases are out of the question. We need more support from our government along with corporate partners to do our work effectively.

We’re doing our part by trimming budgets and looking for creative ways to help our dollars go further. We’re finding additional ways to reach our students and serve our communities, even through challenging times.

We play a crucial role in our regional economies. We bring in the next generation of workers, and we give them the skills they’ll need for the jobs of tomorrow. We incubate new ideas and develop new talent. We provide jobs and invest in our communities.

And now we’re turning to federal, state, and local partners for help. College and universities are key to maintaining the vibrant and ambitious economic landscape of New York. With the help of our partners, we’ll be an integral part of rebuilding it.

***

Marvin Krislov is the President of Pace University. On Twitter @PaceUniversity.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

6 Steps to End Taxpayer-Funded Corporate Welfare in New York

Gov. Cuomo at an economic development event (photo: governor's office)

New York State gives an estimated $4.4 billion a year to corporations to create jobs. Local governments give approximately $5.6 billion more, according to the Citizens Budget Commission. We do not know how much assistance each business gets, nor do we know how many jobs are created or retained. But we do know – as hundreds of studies have shown – that subsidizing corporations is fundamentally a waste of money that could be spent on core government services like transit or schools.

In 2018, Tim Bartik, an internationally prominent labor economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute collated 30 studies that collectively show business subsidies sway business decisions at best 25% of the time. In his recent book “Incentives to Pander,” University of Texas political scientist Nathan Jensen spells out how politicians use corporate welfare for political gain, including soliciting campaign contributions. Jensen carefully shows that fiscal incentives are useless for the public, yet benefit pandering politicians.

In testimony this week to the State Legislature, my organization, Reinvent Albany, listed six steps the state can take to end wasteful corporate welfare in New York:

1. Hold an oversight hearing on business subsidies featuring independent experts.

The Legislature should hold an oversight hearing specifically about the effectiveness of business subsidies in New York state and invite independent experts from across the country. This would help cast light on the amount being spent on the subsidies, the lack of transparency, and the poor return on public investment. There is robust independent scholarship about tax abatements, subsidies for convention centers and stadiums, and other so-called “economic development” expenditures. New York should draw on that expertise instead of hearing mainly from hired guns who are paid by industries getting billions in taxpayer funds.

2. Establish a Database of Deals.

Stunningly, how much each business gets and how many jobs they create and retain is not disclosed to the public and may not be known by the state.

Since 2015, watchdog groups have called for a Database of Deals that reveals exactly how much each business is getting and what the people of New York are getting in return. The public started asking for the Database of Deals following huge scandals that led to the conviction of high-level state economic development officials.

Two years after Governor Cuomo directed Empire State Development to create a database, there is still no database. This is basic transparency. It is 2021 – enough waiting and excuses. The Legislature should reintroduce the legislation (S2815, Comrie/A2334, Schimminger) and require the database in law.

3. Pass the Opportunity Zone Tax Break Elimination Act in the budget.

Subsidies that start small often balloon into incredible costs, and this is why the Legislature must move to repeal New York’s Opportunity Zone tax break by passing the legislation (S1195, Gianaris/Dinowitz) to do so in the budget that’s due April 1. The bill has support from 19 organizations and six unions, including 1199SEIU, Communications Workers of America District 1, and the New York State Teachers Union. Citizens Budget Commission estimated that the Opportunity Zone tax break is costing New York City and State up to $31 million and $63 million respectively each year, with these numbers expected to rise to $140 million and $284 million in 2029.

Under the program, investors receive a tax break by investing their capital gains in so-called “Opportunity Zones,” which are high-poverty or low-income areas designated by states. Investors can defer paying taxes on their capital gains for up to seven years and are excluded from paying taxes on gains from their investments if investing for ten years.