Now's the Time to Boost Social-Emotional Learning, Not Undercut It

Students (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

It is budget season in New York City, a time when we all try to calculate the relative value of the things that are important to us. At a time when young people are struggling to cast off the psychic weight of the pandemic and great social unease, it is common to hear talk of the value of mental health, particularly for adolescents.

If that talk is sincere (and as the Head of School at Children’s Aid College Prep Charter School in the Bronx, I hope it is), then I would expect the relative value of social-emotional learning (SEL) and a reliable, easy-to-use assessment tool to be high. I would expect our city and schools to want to continue making an investment that has paid dividends in better behavior, stronger mental health, and more citizenship. I would be shocked if a city that says it values the social, emotional, and mental health of its young people lets the use of a valuable tool slip away.

Yet that could happen. The city recently told school superintendents in a letter that they could lose access to an important SEL tool on June 29, a year earlier than expected. This would interrupt the city's delivery of SEL to students who need it now more than ever, and would also deprive parents of information about their children's social and emotional wellbeing.

This tool is the Devereux Student Strengths Assessment, but everyone refers to it as the DESSA. It is a rating scale that teachers use to assess students’ SEL-related strengths, such as how well a child works in groups, how often a student offers to help someone, how well a student gets things done on time, and how persistent a child is. Educators more recently have come to understand and accept that we all learn through our feelings and that young people especially are most successful in learning environments that elicit strong, positive feelings.

The DESSA takes minutes for a teacher to complete, but gives the teacher and the school valuable guidance on how well children are using and developing SEL skills and allows schools to make adjustments or spot issues.

It is no secret that young people now are facing plenty of issues not of their own making, yet city kids historically have scored well on the DESSA. My feeling is that to live in this city, all of us – children included – must have a baseline competence in social-emotional skills. It has helped that organizations like Children’s Aid and the Urban Assembly (which organizes support based on the DESSA throughout New York City Public Schools) have made plain the value of SEL and how to measure it.

In this time of anxiety and sparse mental health services, one particular value of the DESSA is to help schools discern the difference between a young person with a mental health problem and one who is enduring the stress of living during challenging times. These things are not the same.

One trend we’ve seen with the help of the DESSA, for example, is that older young people are challenged to maintain optimistic thinking and goal-directed behavior. Right now it can be hard for them to see a clear future when they’ve witnessed or experienced three years of uncertainty, loss, and socio-political turmoil. Understandably, this can create feelings of loss or pessimism, but it’s not a mental illness. Arguably, it’s a rational reaction to the times.

While the DESSA is not perfect (no assessment tool is), it does give educators the language and the ability to see the difference between pessimism and clinical depression. And the DESSA gives teachers a map on how to use SEL instruction to address the social and emotional skills that children as well as adults need to thrive.

We have all collectively lived through a traumatic experience. The way to heal trauma is through positive experiences and connections with others. The use of SEL in school puts a premium on that, and it recognizes that emotionally competent children are better academic performers.

We all want children to learn well. We want them to behave well. And of course we want them to manage themselves well and relate well to others. Let’s not stop investing in a tool that helps make all of that happen.

***

Drema Brown is Head of School at Children’s Aid College Prep Charter School in the Bronx, the educational home of 600 K-8 students. She has been a leader in city schools for 20 years.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

What New York City and State Should Be Doing About the BQE

The BQE (photo: NYC Department of Transportation)

The key question about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) right now isn’t two versus three lanes for the Brooklyn Heights cantilever. It is whether New York City should proceed with its piecemeal Brooklyn Heights project prior to development of a wider corridor plan.

If Mayor Adams and the city’s Department of Transportation (NYC DOT) have their way, downtown Brooklyn and adjacent areas will be forever stuck with a moderately updated version of the BQE as we know it. And their plan comes with an absurd, blighting set of elevated highway ramps NYC DOT has proposed building in DUMBO to make driving through Brooklyn’s densest district even easier than it is today.

The city’s rush to rebuild the cantilever is bizarre and unnecessary when there is strong public and elected appetite for re-thinking urban highways generally, and the BQE in particular. It should be suspended while city and state leaders sort out a framework for taking a longer, harder, and more fundamental look at the BQE and the future of transportation in Brooklyn and Queens.

I was frequently at odds with transportation decision-making during the de Blasio administration, but our past mayor was right when it came to the triple cantilever. Late in his term he called for shoring up the cantilever structures and reducing the rate of deterioration with traffic and weight restrictions, all in order to create breathing room to create a strong, future-oriented plan: “We’re now talking about having the time to do the really big, creative stuff”, he said.

Today the challenge is finding a way to get to the big, creative stuff while preventing Mayor Adams from unalterably locking us in to a transportation infrastructure that promotes urban car use.

Rhetoric about the BQE this winter and spring began building in this direction. Elected leaders across the borough demanded that the city’s limited project be transformed into a city-state plan encompassing the entire length of the BQE. But now that demand needs to be sharpened.

Just “getting the state involved” won’t get us what we need. The state Department of Transportation (NYS DOT) is little better equipped to undertake a thoughtful and creative BQE plan than the Adams Administration. Consider NYS DOT’s track record with highway removal. After decades of pressure from local groups and elected officials, in late last decade NYS DOT changed the little-used Sheridan Expressway from an interstate-style highway to a boulevard. But while pedestrians can now cross the roadway at three signalized intersections, the Sheridan right of way remains a 9- to 11-lane scar across the Bronx cityscape and retains suburban-style ramp connections to both the Bruckner and Cross-Bronx Expressways, all in a corridor with negligible traffic levels. Nothing creative and nothing that could be labeled urban design was applied at all to the Sheridan rebuild. The city played no role at all, even though it has ways to involve itself in state road projects within the five boroughs.

Getting past the state and city agencies committed to keeping cars happy requires a new institution capable of weighing the problems, data, and potential of rethinking the BQE with ideas and applications more beneficial and appropriate than an interstate highway. This has in fact been a key recommendation in thoughtful looks at BQE issues over the past five years, but recently it has been buried under Mayor Adams’ charge at the triple cantilever and in fevered rhetoric about the legacy of Robert Moses.

The Arup/City Council study explicitly called for creation of “a new I-278 corridor governing body,” while the de Blasio expert panel and Regional Plan Association both urged a federal/state/city/stakeholder working group. It’s also the intent behind Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon’s bill to create a BQE public authority.

All that may sound process-y, but we do in fact need to establish one conversation and one decision-making body capable of sorting out everything from today’s tunneling technology and the impact of congestion pricing to an analytic framework for assessing future travel demand broadly and without bias. We sorely lack that today.

Successful highway transformation projects around the world have all framed key goals outside the realms of counting cars and trucks. Tear-down of the Cheonggyecheon Highway was framed as restoration of the cultural and natural heritage of downtown Seoul. Lane reduction on the Peripherique is being cast as an air quality project and opportunity to dramatically expand green space in the outer Paris region. Let’s learn from these and similar efforts, and engage their expertise.

New York has done this successfully before. We have Hudson River Park and a pedestrian-permeable West Street today instead of a superhighway thanks to a multi-disciplinary task force established by Mayor Koch and Governor Mario Cuomo, and decisively including representatives of Borough President David Dinkins. We need something similar for the BQE, encompassing not only transportation agencies, but also city planners, urban design experts, elected officials, and civic stakeholders.

One of their charges should be to examine other cases of urban highway transformations, and they should be empowered to engage consultants with experience in modeling and estimating not just traffic growth, which is all American DOTs seem able to imagine, but how demand in the BQE travel market could be accommodated or managed differently, with better outcomes for the city and its neighborhoods. For example, perhaps the anticipated Interborough Express doesn’t need to sit at the back of a very long MTA project queue, but could instead be folded into a Brooklyn-Queens corridor program, and built with highway funds as a way to ease demand for BQE car trips.

Once they’ve read this, I certainly don’t expect Mayor Adams and Governor Hochul to decide they agree and begin to act. Perhaps one way to elevate the issue and provoke action is for engaged elected officials to assemble their own expert group to further develop the framework for a corridor-wide approach, directly challenging the city’s piecemeal effort. Such an undertaking needs to be clear that Mayor Adams’ drive to impose a “solution” for the Brooklyn Heights cantilever will almost certainly foreclose other options and predispose any look at the corridor toward the status quo.

Unfortunately, piecemeal is how New York does most things. Public interest in the BQE is a chance to change that for transportation in the city’s most populous borough and beyond, if we seize the opportunity.

***

Jon Orcutt is a transportation policy consultant, long-time transportation reform advocate, and was NYC DOT Policy Director from 2007 to 2014. On Twitter @jonorcutt.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Mayor Adams: Uphold the Working People's Agenda and Invest in Job Training as a Public Safety Solution

Mayor Adams speaks at a "hiring hall" (photo: Ed Reed/Mayor's Office)

Mayor Adams’ 2023 State of the City address had a theme. He called it the Working People’s Agenda. Adams asserted that job development, especially for the Black community, would be a top priority.

At Exodus Transitional Community, we’ve been putting the mayor’s agenda themes to work for years. Exodus is a preventative, reentry, and advocacy organization led and staffed by formerly incarcerated New Yorkers. We provide workforce development offerings, specifically job readiness programming and placement services. Our Employment Specialists support people in maintaining employment as well as in advancing their careers.

In 2022, we served over 900 justice-impacted people with career readiness services, placing 450 people in employment positions. As a result, families are now supported because their loved ones were able to secure jobs and become responsible tax-paying citizens. The payoff for the wider community in New York City also includes greater public safety.

In addition to providing direct services, Exodus advocates for a society in which all can achieve social, economic, and spiritual well-being. We co-chair the Employment and Entrepreneurial Subcommittee on the Commission for Community Investment and the Closure of Rikers Island. We have worked alongside activists for years in the fight to close the Rikers Island jail complex.

The Commission has called for significant investments in employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for formerly and currently incarcerated New Yorkers. We know that ensuring people have stable housing and employment are the two greatest factors in reducing recidivism.

Roughly 95% of the people who are detained or incarcerated will be released back to our communities. To ensure community safety, we must invest in people and communities – job training and placement opportunities are key. What we see daily in our programs is backed up by extensive research that shows increased income and decreased unemployment have direct effects on reducing crime.

Unfortunately New York City has been behind many other large cities in bouncing back from the high rates of job loss and unemployment caused by covid. This calls for targeted action and scaling up the programs that work.

Our Employment Services Program is filled with inspiring success stories of people returning from incarceration. Vernon, for example, was unemployed with no marketable skills. By chance, he met the Office Manager at Exodus near his neighborhood park where they discussed potential employment opportunities. Vernon became involved with Exodus, attending and completing Walking through the Wilderness, our job readiness program. His job search reached a breakthrough with a national, full-service security firm based in New York, where he works as a licensed security guard and is regarded as a highly motivated individual. Vernon personifies what works.

Vanessa’s story is another example of Exodus’ workforce development program in action. She came to Exodus striving to work in the healthcare field. However, she struggled during interviews in communicating that she had the transferable skills needed to be an ideal job candidate. Our Employment Specialists stepped in and coached Vanessa through extensive mock interviewing sessions. Vanessa’s breakthrough came when she was hired as an Office Administrator in a medical facility. Her resilience has become an inspiration to others.

Vanessa, Vernon, and the many other people Exodus serves have at least one thing in common: a burning desire to put their talents and abilities to work and provide for themselves and their families.

“You need good jobs and pathways to get those jobs,” Mayor Adams said — and we agree. The work Exodus and the Commission for Community Investment and the Closure of Rikers Island do is aligned with these goals, and it also serves another valuable function — investing in the lives of our most vulnerable New Yorkers. We don’t need a ‘Plan B’ for closing Rikers, we just need Mayor Adams’ budget priorities to line up with his professed intentions. Then we will see a reduction in incarceration alongside a more robust workforce.

Unfortunately, the Commission’s recommendations have not been taken seriously by Mayor Adams, and contracts for nonprofits that provide workforce development have been cut citywide. Yet Rikers continues to get paid for what doesn’t work – to the tune of over $550,000 per incarcerated person per year. Instead of investing in solutions to scale, such as workforce development programming and training, our City is languishing in debt from a mismanaged Department of Correction and our community members are literally dying on Rikers Island. We can and must do better as a city.

***

Brittany Smith is Associate Vice President of Workforce Development and Kandra Clark is Vice President of Policy & Strategy at Exodus Transitional Community. On Twitter @etcnyorg.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ensuring Our City’s Landmarks Reflect Our City’s Diversity

The New York Eye and Ear Infirmary

New York is perhaps the most diverse city in the world. Few places on Earth can claim to be home to so many sites of important contributions to the history of groups as varied as African Americans, Latinos, women, LGBTQ+ people, and the disabled community, to name just a few.

But too few of our city’s officially designated landmarks reflect that wonderfully rich and diverse history, though preservationists and communities across the city have been laboring hard to change that. The City, however, has been slow to act — particularly when sites are endangered.

One need look no further than 14th Street, one of New York’s defining thoroughfares, for evidence. On and just off what was once called “the poor man’s Fifth Avenue” are an incredible array of sites connected to these multifaceted histories New York embodies. Several are imminently endangered, and all are awaiting action by the City to recognize and preserve that precious history.

Starting from the west, the former Our Lady of Guadalupe Church at 229 West 14th Street was the very first New York church established for a Spanish-speaking congregation. Originally serving Spaniards, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and other Latin Americans, the church’s congregation grew over the years as did New York’s Hispanic population — now encompassing about 30% of all New Yorkers. But less than a handful of New York City’s thousands of designated landmarks reflect the history of our rich and varied Latino community. The church has been closed, and may soon be sold for development.

Just east at 50 West 13th Street sits the Jacob Day house, once the home and place of business of one of 19th century New York’s most prominent and successful Black businessmen. Day was also a leading crusader for reform of New York’s racist voting laws (which placed unequal property requirements upon Black New Yorkers), and a prominent abolitionist whom evidence indicates helped the Underground Railroad. The recent death of a longtime owner who had pledged to preserve the house leaves its fate very much in doubt.

Footsteps away at 80 Fifth Avenue and 14th Street sits the former headquarters of the very first national LGBTQ+ rights organization in the country, then known as the National Gay Task Force. From there, between 1973 and 1986 the Task Force got the first national gay rights legislation introduced, homosexuality removed from the list of mental disorders, the ban on gay people working for the federal government lifted, and the first White House meeting for an LGBTQ+ group, all while combating HIV/AIDS, anti-LGBTQ+ violence, and workplace discrimination.

Across Fifth Avenue at 10 West 14th Street stands the former headquarters of the NYC Woman Suffrage League. Beginning 130 years ago, multiple campaigns were led here to extend the franchise to New York’s women. That decades-long struggle finally succeeded in 1917, just three years before the 19th Amendment made it the law of the land nationwide.

And just a bit further east at 218 Second Avenue/301 East 13th Street sits the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary (NYEEI), founded in 1820 as the first specialized hospital in the Western Hemisphere, and New York’s second oldest hospital. Over two centuries, NYEEI offered groundbreaking care and services for people with visual and hearing disabilities. The existing building, the oldest part of which dates to 1856, is where Helen Keller spoke at the 1903 ribbon cutting for its final section. The historic structure is now endangered by a reorganization plan that staff and patients oppose, arguing it will destroy both the services and the building.

For years now, we have been urging the City to consider these sites for landmark designation, even as the clock has been urgently ticking on several of them. They are just a few examples of the underrepresented histories that are awaiting action by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC). Women, African Americans, Latino New Yorkers, the LGBTQ+ community, and disabled New Yorkers collectively make up the vast majority of our city’s residents. But only a tiny fraction of our city’s recognized and protected landmarks speak to their histories.

Progress has been slow, especially on endangered sites. Many sites representing diverse histories the LPC has designated, like the Stonewall Inn or the James Baldwin House, were previously landmarked for other reasons, and thus already protected and in no danger.

Others, like the former Colored School No. 4 in Chelsea, took years of relentless campaigning by the public, led by African American historians, to get the City to act, even though it was an empty, City-owned property with no other planned use.

Change in our city is inevitable. But too often the price for such change is the erasure of the histories of New Yorkers with the least power and privilege. The city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission has the ability and the obligation to change that. These sites, on and just off 14th Street, along with others elsewhere across the five boroughs, present a critical opportunity for them to do so. Now is the time for the City to act, before it’s too late.

***

Andrew Berman is Executive Director of Village Preservation. On Twitter @GVSHP.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York’s Compassionate Release Laws were Designed to Keep People from Dying Behind Bars; They’re Failing

On the inside (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Even if he were younger than his age of 80, Diego’s health condition would be dire. A heart attack has left him with a weakened heartbeat. He cannot walk very far, and a physician has recommended that he not climb stairs and should only perform sedentary activities. He was recently rushed to the hospital because his ailing heart could not pump properly, and his lungs filled with fluid. It will likely happen again – if his heart does not completely give out in the meantime.

People with heart failure, like Diego, have poor odds of living for very long.

Diego is also a New York State prisoner. He has been incarcerated for 40 years. He will likely perish in prison despite a law allowing him to die at home, as his request for medical parole, like that of countless others, was summarily denied. This despite the existence in many jurisdictions of what is often referred to as compassionate release mechanisms ostensibly enacted to allow people to die surrounded by family and with some small measure of comfort and dignity. (We changed Diego’s real name to protect his privacy.)

In 1992, New York State adopted a medical parole statute in recognition that incarcerated individuals suffering from terminal disease spent their final days far from their families and at a significant cost to the state. In 2009, the law was expanded to grant incarcerated individuals release if they suffer from a non-terminal condition that renders them so debilitated, mentally or physically, as to be severely restricted in their ability to self-ambulate or to perform significant normal activities of daily living. As stated in the New York Board of Parole’s 2020 legislative report, the medical parole law represents a “compassionate and practical response to dying incarcerated individuals.”

The implementation has been neither compassionate nor practical.

In our experience, the application of the law is rarely compassionate. Despite the humane and moral impetus for the laws, from 2016 to 2020, only 60 people were released pursuant to medical parole. Meanwhile, a study from Columbia University’s Center for Justice found that nearly 1,300 people died inside New York State prisons from 2010 to 2020. Thus, a person dies behind the walls every three days. Surely, many of the 1,300 met the statutory requirements for medical parole. After all, numerous New York prisons have their own hospice units, and there are several Regional Medical Units (RMU) for the severely ill.

When someone submits a request for medical parole, the opaque process of eligibility often leads to unsubstantiated denials. Not long ago, we began working with Frank (not his real name), a middle-aged man with stage four pancreatic cancer. His cancer was incurable, and death was imminent.

Despite his grave illness, he received a three-sentence denial stating that he was not an “appropriate candidate” for medical parole. The bureaucratic official rejection letter he received was originally for someone else, had that person’s name crossed out, with Frank’s name scrawled in its place. Frank died in a New York prison several weeks later.

In the case of Diego, an independent physician provided a detailed report outlining how his conditions qualified him for medical parole. The physician was a volunteer with the Medical Justice Alliance (MJA), a network of over 200 medical professionals in 24 states who volunteer their time and medical expertise to protect the constitutional rights of those in carceral facilities. The New York Department of Corrections’ chief medical officer denied the request for medical parole without any written explanation of the reasons. The MJA volunteer reached out to better understand the medical basis for their decision. Two months later, he has yet to receive any response.

Neither has the implementation of the medical parole law been practical. Even if a person is deemed eligible for medical parole, the length of the process means that they often die in prison before they are released. People must complete a parole interview, which can take weeks to schedule. Furthermore, the process of testifying before the New York parole board significantly taxes people who are near death. One person we know was interviewed despite being unable to speak more than a few words before having to stop and gather his breath with the aid of an oxygen tank.

We agree with the parole board in seeking a “compassionate and practical response to dying incarcerated individuals.” However, the current failed implementation has allowed over a thousand people to perish in New York prisons despite many who should qualify for release under the law.

We advocate for simple reforms to improve implementation of the New York law – regularly referring people who qualify for hospice or RMUs; utilizing independent physicians to evaluate whether persons qualify for medical parole; increasing transparency by providing detailed explanations when a request for medical parole is denied; abandoning the parole board interview in favor of a brief review of the medical facts, release plan, and any public safety concerns; and studying every case where a person perishes in prison to determine why they were not granted release pursuant to medical parole. Such reforms would reduce the heavy emotional and financial burdens of keeping incarcerated those people near death.

***

By William Weber, MD, MPH, Medical Justice Alliance; Brooks Walsh, MD, Yale-New Haven Health System; and Steven Zeidman, Professor, CUNY School of Law.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

For Long-Term MTA funding, Look to a State Carbon Tax

Subway ridership in view (photo: Marc A. Hermann/MTA)

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and an announcement from Gov. Kathy Hochul, the agreed-to 75% rise in the tax rate on employee salaries paid by businesses in the five boroughs will add $1.1 billion to the PMT’s ongoing annual $1.8 billion take.

(The numbers prorate imperfectly because the rise in the tax rate, to 60/100 of one percent, applies only in the city; the rate in the seven suburban MTA counties remains 34/100 of one percent.)

The upward bump in the PMT is part of the package to avert a fare hike and service cuts that would have jolted the entire metro region. Raising the same $1.1 billion via the subway farebox, for example, would have required a whopping 35% jump in fares, a calamity that would have triggered enough new car, cab, and Uber trips to slow vehicles in Manhattan by 5% and boosted city and regional carbon emissions by nearly 400,000 tons of CO2 a year — enough to negate the climate benefit of 90 new large wind turbines, according to my modeling. And these figures don’t include lost jobs and commerce from worsened transportation. Reducing service to save the same amount would have produced similar bad outcomes.

Score a big win, then, for transit and New York. But the new revenue comes with a downside: taxes on payrolls discourage hiring and compound our area’s anti-business aura. Moreover, this revenue infusion will almost certainly be not the last but the first in a series the MTA will require throughout the decade to limit future fare hikes and improve service even as ridership continues to lag pre-pandemic volumes. Counting on raising the PMT next time, and the time after that, will be a fool’s errand. There has to be a better way.

I believe there is: enact a modest statewide carbon tax and dedicate a third to a half of the revenue to shoring up public transportation budgets around the state, though principally in New York City.

Reappraising Carbon Taxes

On January 1, Washington state launched its carbon-pricing program, the nation’s second all-sectors carbon charge, with a starting price around $20 per ton of CO2, though most of the emission allowances fetched even higher prices in the first carbon auction, in March. I estimate that the same $20 price applied to all fossil fuels burned in New York State could generate revenues of $3 billion a year (see table).

Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state.

Even with these allocations, roughly half of the new $3 billion in annual carbon revenues would remain available for a range of purposes from home weatherization to rebates offsetting higher fuel costs for lower-income rural New Yorkers.

Of course, no new tax is ever welcomed with open arms. In recent years, moreover, carbon taxing has lost political standing with left and right alike.

|

|

|

Right-wingers, in thrall to fossil fuels, denigrate the very idea of climate concern. Opinions on carbon pricing on the left, while far more nuanced, tend toward an “eat your peas” quality, seeing the promised revenues but not the powerful tides unleashed by the increased fuel prices.

Could a state carbon tax have a chance in New York this time around? I believe so, if only because MTA deficits are untenable and a statewide carbon tax looks like the least-bad long-term antidote.

Consider:

- New York wouldn’t be the first state to price all carbon emissions. California has done so for a decade, and, as noted, Washington just followed suit.

- Two-thirds of the $3 billion in carbon tax revenue could go to other, non-MTA uses across the state.

- Nearly half of the revenues would come from charges on fossil (natural) gas, the very fuel that climate activists are targeting in order to electrify heating and cooking while also shrinking climate-damaging methane leaks from pipelines, wells, and buildings.

- Carbon taxing’s regressive bias (it takes more dollars from the rich but more proportionally from the poor) would be blunted by its helping keep a lid on transit fares.

- The affluent suburban counties that will be on the hook for the carbon tax caught a big break by their exemption from the increase in the Payroll Mobility Tax. Moreover, some pro-climate suburbanites might even support a climate-helping carbon tax.

- Upstate households will be cushioned from the tax by the region’s preponderance of low-carbon electricity from nuclear, hydro, and wind power.

- Aid to transit could be packaged as an urban corrective to suburban- and rural-facing Inflation Reduction Act federal subsidies for solar panels, electric vehicles, and heat pumps. (Notably, the IRA does not fund urban-friendly mass transit and e-bikes.)

- Left-leaning climate-justice advocates who shy away from carbon pricing might warm to a policy that cuts emissions by attracting car trips to buses, trains, and subways.

This panoply of advantages points to diverse potential sources of support for a transit-benefitting state carbon tax:

- NYC transit and “livable streets” advocates;

- Economic-justice advocates who recognize affordable transit’s value in combating poverty;

- Climate campaigners who see carbon pricing as a complement to other carbon-cutting policies;

- Suburbanites concerned that future hikes in the Payroll Mobility Tax will come for them;

- “Electrify-everything” proponents working to eliminate fossil gas from residences and other buildings;

- Developers of low-carbon electricity — not just solar and wind providers but proponents of retaining the state’s four upstate reactors and building new ones;

- Energy-efficiency engineers, contractors, and workforces;

- Labor unions whose members fabricate, erect, and maintain the spectrum of green energy projects that a carbon tax will help make more abundant by making fossil sources costlier.

Competing Claimants?

Electricity producers in New York already pay a carbon fee under the multi-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) cap-and-trade program. In addition, Governor Hochul and the statewide climate coalition New York Renews have advanced competing carbon pricing concepts, both of them, somewhat confusingly, dubbed cap-and-invest. Hence, an MTA-focused carbon tax, which would employ a carbon-based charge on fossil fuels extracted or imported into New York State rather than a carbon cap enforced through sales of emission permits, wouldn’t arrive on a blank slate.

RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating $365 million of statewide revenues a year, paid as surcharges on power bills, which goes to support investments in energy-efficiency and renewable electricity. While in theory the RGGI charge could be netted against the new carbon tax, the relative ease and importance of decarbonizing electricity production make it preferable to retain it and add the carbon price on top.

Cap-and-invest presents a trickier set of issues, partly because neither the governor’s prospective program included in the new budget nor NY Renews’ more elaborate plan has been fully fleshed out. In addition, the latter is the fruit of years of deliberation and consensus-building among the coalition’s hundreds of participant grassroots groups, who now constitute a formidable host.

At this writing, NY Renews envisions applying $10 billion in carbon revenues over several years in no less than 73 individual spending buckets grouped in four uber-categories: Climate Jobs and Infrastructure includes elements like aiding electric bus manufacture ($100 million) and offshore wind power supply chains ($300 million). Energy Affordability earmarks $1 billion to wipe out utility customer debt and $2 billion to support building electrification. Community & Worker Transition Assistance devotes $600 million to the “just transition” from jobs in carbon fuels to positions in renewable energy. And Community Directed Climate Solutions sets aside $2 billion to unspecified projects in historically underserved and overburdened urban neighborhoods and rural areas.

The NY Renews plan should be seen, then, as a holistic roadmap to make over not just how energy is supplied in the state but how it is consumed and governed. Billion-dollar-a-year allocations to the MTA aren’t the kind of investment its members have envisioned. Nevertheless, exploratory calculations suggest that the carbon payoff from service improvements paid for by a state carbon tax would be impressive.

As an illustration, I have calculated that an average 20% speed-up in subway trips achieved by running more trains at higher speeds would save straphangers and drivers each around 100 million hours a year (the latter from car trips switching to trains) while reducing car and truck emissions by 900,000 tons a year. Even more CO2 would be eliminated because of New York City’s improved competitive advantages vis-a-vis less “inherently green” suburbs and exurbs.

To be sure, so striking a gain in subway performance would almost certainly carry a price tag well over a billion dollars a year. Still, the prospective benefits underscore both the carbon-cutting potential of infusing new funds into subway service and the need to score competing claims for their climate value.

Broader Considerations and Next Steps

Over time, the carbon tax’s revenue base will shrink as its price incentives kick in and other carbon-cutting policies also gather steam. The resulting loss in tax revenues could be counteracted by periodically raising the per-ton tax rate. New York City could supplement the tax through revenue-generating street-management measures such as curbside pricing and other forms of road pricing.

Earlier this year, Community Services Society CEO (and MTA board member) David R. Jones and Riders Alliance executive director Betsy Plum proposed expanding New York City’s Fair Fares program to allow an additional 772,000 lower-income New Yorkers to qualify for half-fare transit passes. The cost, which they put at $142 million a year, should be a candidate for the carbon spending package.

This discussion has centered on the carbon tax’s creation of a new funding pot to maintain and improve transit affordability and performance. But taxing carbon emissions stands to benefit society in two other major ways. It will diminish financial incentives propping up carbon fuels and also support societal paradigms promoting care over harm.

A carbon tax is more than just a pay-for, in other words. Simply making it more expensive to buy and burn carbon fuels discourages fossil fuel use in a multiplicity of ways. Moreover, the very act of pricing carbon emissions can spur “externality taxing” in other realms, from congestion pricing to taxing the sugar content of soft drinks. Making New York the third U.S. state with broad-based carbon pricing will also add momentum to long-sought federal carbon emissions pricing.

Shoring up MTA finances, while reason enough to enact a state carbon tax, isn’t the lone consideration. The crisis of transit funding should be seen as a catalyst to pricing fossil fuels more closely to their true societal costs — a vital goal in its own right.

The next MTA funding crisis-as-opportunity will be upon us soon. The Legislature should move swiftly to study the benefits of taxing carbon emissions as a way to hold the line — and more — on transit fares and service, well in time for next winter’s budget negotiations. Transit and climate advocates and their counterparts in the Hochul administration should consider integrating a transit-focused carbon tax into their agendas.

Taking $3 billion a year for any public purpose, no matter how noble, is no small matter. The time to start selling a transit-supporting state carbon tax is now.

***

Charles Komanoff is a long-time policy analyst and environmental activist who directs the Carbon Tax Center. On Twitter @Komanoff.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Importance of the New York Court of Appeals

The Court of Appeals (photo: Mike Groll/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul)

Courts are much in the news these days. The Supreme Court’s recent rulings on abortion, gun control, and other issues have stirred controversy. Here in New York, the lengthy process of the governor nominating and the Senate approving a new Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals has raised public interest in the Court’s role. People are reminded that the courts, particularly the state’s and nation’s highest courts, are the final arbiters of crucial public policy issues. Their decisions have far-reaching consequences for our lives.

That highlights the importance of the New York Court of Appeals. The state’s highest court is the forum of last resort in deciding social, economic, political, and constitutional issues that are essential to New Yorkers. Even more, since its creation in 1846, the Court of Appeals has arguably been the most important state court in the nation, the one that the highest courts in other states, and sometimes the U.S. Supreme Court, look to for insight. The high court’s status and prestige was so high that one of its Chief Judges, Alton B. Parker, was nominated for president of the United States by the Democratic Party in 1904 (he lost to Theodore Roosevelt).

The Court of Appeals’ role is further underlined by the fact that, during most of our history, the key social, economic, political, and constitutional issues were settled at the state level. Litigation in the federal court system, commonplace today, was in the past more limited. Appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court were more rare than today.

Why does the New York Court of Appeals matter so much?

The Court of Appeals is sometimes seen as something of a buffer and a bulwark of liberties.

“It is vital that we restore the court to its position of national pre-eminence and ensure that the public is confident in the court’s integrity,” said Associate Judge Rowan Wilson in his Senate confirmation hearing to be Chief Judge (he was soon confirmed). “The court’s role and legitimacy is particularly important now, in the face of the U.S. Supreme Court’s retreat from several of its seminal decisions.”

“State courts are where the issues that are most important to the day-to-day lives of New Yorkers get addressed,” said Caitlin J. Halligan in her Senate hearing to be confirmed as a new Associate Judge of the court, succeeding Rowan Wilson (she was soon confirmed). “It is where the scope of the New York constitution gets hammered out, a task that is especially important at a moment when federal courts appear to be pulling back on some key constitutional protections.”

Judith Kaye, Chief Judge from 1993 to 2008, wrote that “state court dockets comprise the battlefields of first resort in social revolutions.” They must exercise judicial discernment and judgment. “State courts have openly and explicitly balanced considerations of social welfare and have fashioned new causes and action where common sense justice required.”

The Court of Appeals is a model of judicial deliberation.

The high court considers cases that have already made their way up through the state court system, including the supreme court and appellate division. Extensive evidence is presented and considered in those courts. The Court of Appeals reviews the procedures and decisions in the lower courts to make sure that the proceedings were fair and that the law was applied correctly and in line with provisions of the state and U.S. constitutions.

The court has seven members, the Chief Judge and six Associate Judges. Court decisions are collective ones, reached after careful discussion among the judges where conflicting perspectives are aired and alternative outcomes proposed. The Chief Judge presides and may try to persuade his colleagues one way or the other, but the associate judges are independent-minded and the Chief Judge’s influence is limited. Individual judges try out proposed opinions, listen to each other to gain insights, and hold extensive discussions.

Courts are well aware of the importance and consequences of their roles. They expect scrutiny of their decisions. They weigh and balance lots of factors. They recognize the need to explain the basis for the decisions. Sometimes, this results in arbitrary, biased decisions. But usually it results in decisions that are reasonably balanced and carefully explained even if that does not align with various groups’ views of what they think the court should have done.

The Court exercises a high degree of judicial statesmanship.

The Court of Appeals often strikes a judicious balance between two positions. The first is the conservative philosophy of interpreting the constitutions narrowly, focusing on the original meaning of their provisions, and clinging to the precedent of past court decisions – the legal doctrine of “Stare Decisis,” a Latin term that means “let the decision stand.”

The second position is to be more expansive, construing the constitutions more broadly, looking for ways to interpret them in light of contemporary life, thereby keeping them fresh and relevant.

This may sometimes involve articulating “common law,” sometimes called “judge-made law,” defined by the Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute as “law that is derived from judicial decisions instead of from statutes.” Courts do this cautiously, basing their decisions on the implications of the constitutions and precedent or analogy to other decisions. Their decisions, in effect, become law.

State legislatures may nullify a decision by passing new legislation to do so. More often, the legislatures take heed of the court’s reasoning and often codify common law rules from the courts of their state, “either to give the rule the permanence afforded by a statute, to modify it somehow (by either expanding or restricting the scope of the common law rule, for example) or to replace the outcome entirely with legislation,” as the Cornell Legal Information Institute explains.

The “judge-made law” role may sometimes put the high court in a somewhat uncomfortable, high-visibility position. As Chief Judge Kaye wrote, “given the enormous volume of state court litigation, the unending array of novel fact patterns pushing the law to progress, and the inability of state legislatures to react immediately to the many changes in society…courts interpreting statutes and filling the gaps have no choice but to ‘make law’ in circumstances where neither the statutory text nor the ‘legislative will’ provides a single, clear answer.”

The Court of Appeals can be expected to continue deciding tough, high-consequence cases. Its new Chief Judge and new Associate Judge may change the Court’s take on constitutional issues somewhat. But it seems likely that the court will continue, and may even expand on, its history as a judicious but proactive court.

Judges in writing their opinions, and courts in issuing their decisions, have as one audience other judges, attorneys, others involved in the cases, legislators, and others. But they also intend their opinions for the media and for the general public. The media of necessity summarize decisions and editorial writers, pundits, and partisans may pick out particular points and put their own interpretation on the decision. But interested members of the public can and should read the decisions for themselves. They are posted on the courts’ websites. Sometimes the decisions may seem laden with legal jargon. But the best ones are clear, distinct, and direct.

***

Bruce W. Dearstyne is a historian specializing in New York history. In 2022, SUNY Press published the second edition of his book The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History and his newest book The Crucible of Public Policy: New York Courts in the Progressive Era.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

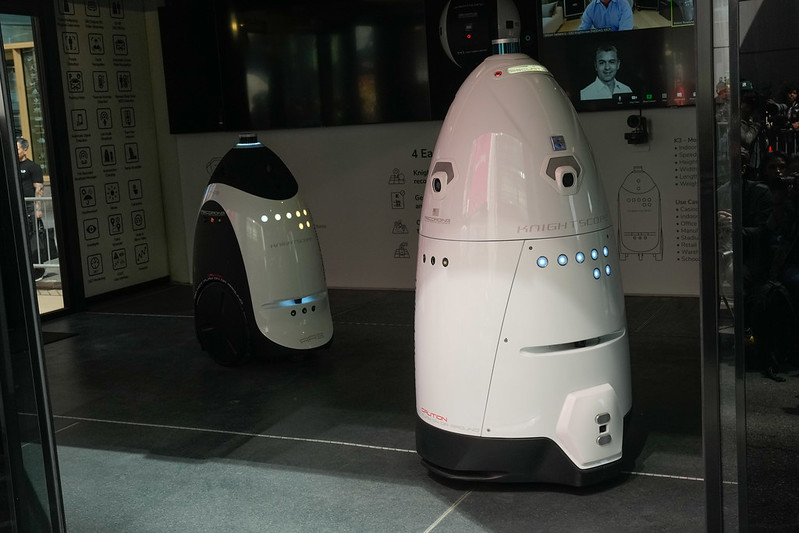

New York City Finally Faces Down Facial Recognition

New NYPD technology (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Many of you have heard some of the horror stories already, how facial recognition technology can track our movements in truly creepy ways. For some people, the moment of realization came last winter, when a mother was ejected from the Rockettes and threatened with separation from her daughter through use of facial recognition.

Proponents of the creepy tracking tech claim it keeps us safe, but what was this mother’s crime? She worked for a law firm that had sued the owners of Radio City, where the iconic Christmas show is performed.

The case showed so many that the threat from facial recognition simply can’t be ignored any longer, but we have been doing just that, ignoring the growing threat for years. Facial recognition already tracks New Yorkers at work and at home. It tracks where we shop and where we seek out entertainment. It’s seemingly everywhere, but oftentimes we have no idea.

That may soon change. This week the New York City Council is considering legislation that would begin to ban facial recognition and other biometric technology. If landlords or store owners want to use your body to track your movements, that abuse may soon be a thing of the past. And the legislation couldn’t come a moment too soon.

My colleagues and I first began calling for a ban on facial recognition more than two years ago as part of the Ban The Scan coalition. Since then, the technology has only become cheaper and more easily abused. Surveillance vendors not only scan our faces, but often take images from social media, using our personal photos to track us against our will.

Some of you may use your face to unlock your phone or computer. Don’t worry, that won’t change. Using your face to unlock a device is night and day compared to using millions of New Yorkers’ faces as a tracking tool. If you choose to use facial recognition for convenience, that’s your choice. But the technologies being used in housing, stores, and elsewhere today are used against us, not for us.

These systems log our movements and make our location accessible to landlords and the companies that own stores and venues like Radio City. For tenants, this can mean being watched in your own building, having a constant log of your movements and visitors.

This is particularly alarming for rent-stabilized tenants. Landlords can use these logs to claim a tenant isn’t using an apartment as their primary residence, when really they’re absent for another reason, such as being in the hospital.

Cheap, ubiquitous tracking isn’t a feature, it’s a threat. How can you tell? Landlords and store owners never allow their own movements to be tracked in the same way.

James Dolan, the owner of Madison Square Garden and Radio City, whose facial recognition barred that mother from the Rockettes, shows publicly what can often go unseen. When facial recognition and other forms of biometric tracking go unchecked, the rich and powerful can use it however they see fit. They can settle grudges, target rivals, and silence critics.

What’s unusual about Mr. Dolan isn’t that he abused the technology at his fingertips, but that he was so open about it. Imagine a city where anytime you post something negative on social media about a company you risk being barred from their premises for life. That sort of corporate tyranny isn’t possible without the cheap, ubiquitous tracking enabled by facial recognition.

But as important as the pending City Council legislation may be, as crucial as it is to safeguard New Yorkers from this tracking at home and in public accommodations, there still is a vital piece missing: The NYPD.

Police use of facial recognition grew rapidly in recent years, with tens of thousands of New Yorkers scanned by the technology. Even as the tech is proven to be biased against Black, Latino, and Asian New Yorkers, and after a string of high-profile facial-recognition-fueled false arrests across the country, the NYPD has made no effort to address its dangerous use of this error-prone technology.

Just as with stores and landlords’ facial recognition, we’ve called for years for a ban on police use of the technology, only to be stalled by City Council bureaucracy. As we finally take these crucial, belated steps to address the technological tracking trauma inflicted on New Yorkers every day, we must also finally bring forward legislation to ban New York City’s own abuse of the technology. Only then will we truly be able to safeguard our city from the dystopian future these technologies threaten.

***

Albert Fox Cahn is the founder and executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (S.T.O.P.), a New York-based civil rights and privacy group, a TED fellow, a Technology and Human Rights Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Carr Center, and a visiting fellow at Yale Law School’s Information Society Project. On Twitter @FoxCahn & @StopSpyingNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Why We Should Abolish the NYPD's Gang Database, Not Reform It

Mayor Adams and NYPD officials (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayor's Office)

This week's report from the Office of the Inspector General of the NYPD (OIG), pointed out numerous irregularities in how the NYPD manages their Criminal Group or “gang” Database (CGD). While these irregularities in procedure confirm our concerns that the database is overly broad, racially discriminatory, and arbitrary, the procedural reforms proposed by the OIG fail to address the larger unexamined issues of whether the existence of such a database is good policy. We think it isn’t and instead support City Council bill 360 that calls for the abolition of the gang database.

In 2018 and 2019 the Grassroots Advocates for Neighborhood Groups & Solutions Coalition (GANGS) testified before the City Council about our concerns that the database uses overly vague criteria for including people in the database, lacks oversight, includes juveniles without notifying their parents, refuses to tell people if they were on the database, and offers no mechanisms for disputing inclusion. The new OIG report confirms all of these concerns.

The fact is that secret databases like this inevitably give rise to shortcuts, arbitrariness, and discrimination. For instance, the OIG found numerous instances in which people were added based on a singular social media report or based on the undocumented allegations or without the required sign off by a supervisor. In addition, entire public housing developments have in essence been labeled a “known gang location” making anyone living there subject to inclusion on the list.

The OIG report also confirmed earlier reports that 99% of those on the list are non-white. In essence, they have defined “gangs” in such a way that they only include people from non white communities, despite the fact that violence, drug dealing, and other collective criminal behavior occurs in a wide variety of neighborhoods. In addition, there are many juveniles in the database including some who are 11 years old. No effort is made to communicate with their parents or provide these young people with much-needed support.

While the OIG report documents a variety of procedural failures it starts off with a claim that it couldn’t find any harms related to inclusion on the database, but later admits that it didn’t really look for them because they would be difficult to find methodologically. But this flies in the face of other reports by similar offices that were able to identify concrete harms. The OIG for the Chicago Police Department found misidentifications, harassment, obstacles to immigration, and racial profiling, all of which they argued furthered the historical divide between the community and the police and contributed to inequities, especially in communities of color.

The GANGS Coalition members have already documented concrete harms including the use of gang designations to deny people bail, enhance sentences, deny someone employment with the city, and contribute to differential treatment by police on the street. While the NYPD OIG found that the database plays a role in how street level policing is conducted, it made no effort to assess whether that treatment might involve unwarranted harassment and abuse, which has been found in other cities and which our members report.

All of this and more has led many to contemplate reforming the database by putting in place more transparency and oversight, but such efforts are both ineffective at getting at the real problem and doomed to failure.

The NYPD has made it clear that it opposes any meaningful reforms and has a history of obstructing them.The OIG report calls for the notification of parents whose children are on the database as long as it doesn’t compromise an existing investigation. But, when the City Council floated this idea, the NYPD said that it would oppose this because of its belief that everyone on the list meets the definition of being part of an active investigation.

We must also ask what the ultimate purpose of reform would be. Small procedural changes to the database generally serve to reinforce the use of police to manage the problems of youth violence.

There are alternatives. The Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice supports several Cure Violence sites that employ community outreach workers known as “credible messengers” to work in high violence communities to identify and respond to potentially violent situations and work with young people to try to break the cycle of retributive violence as well as help young people develop positive paths forward through educational and vocational supports. In addition, they are ramping up an Advance Peace program based on the successful ones in California that enroll high-risk young people in a variety of services and provide them with income support and financial bonuses for sticking with the program. Research shows that these initiatives work.

But we need to do more.

Newark’s new Office of Violence Prevention and Trauma Recovery is a possible model. Newark Mayor Ras Baraka diverted police funding to create the office, which is using the money to create a holistic community-based response to violence that includes youth programs, outreach teams, intensive trauma counseling, summer jobs, and employment and education support. Violence in Newark is at a 60-year low with significant reductions in homicides and shootings last year. While New York City has some of these programs, they fail to cover many parts of the city and aren’t run cohesively to provide an integrated holistic approach the way that Newark does.

Abolishing the Gang Database will establish the illegitimacy of the tactic of placing large numbers of young men and boys of color in databases based on the suspicions of police. It will be a step towards shifting our emphasis away from “building cases” to repairing harms. The database is a crude and flawed tool that implicates the innocent and fails to adequately address the needs of those young people who are at risk of violence as either victims or perpetrators. Young people involved in violence have all been victims of violence themselves in ways that were never adequately addressed, leaving them scarred, angry, and often alone. If we want to end the violence we need to lift these young people up before the violence, not lock them up and throw away the key after the violence has already happened.

***

Victor Dempsey is community organizer for the Legal Defense Fund. Alex S. Vitale is Professor of Sociology at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Both are members of the GANGS Coalition. On Twitter @avitale.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

What Behavioral Scientists Tell Us About Pay-to-Play in Government

Gov. Hochul delivers a check (photo: Darren McGee/Governor's Office)

Here’s a story you’ve probably heard: A CEO donates $50,000 to a state governor’s political campaign. Not long after, the CEO’s company gets a $50,000,000 contract from the state. A reporter asks the politician if it was pay-to-play, and the governor’s office says: “No donation of any size has any influence on the governor’s decisions – period.”

The politician may truly believe this, but a substantial body of research suggests the opposite: When people receive a gift, they want to return the favor. Reinvent Albany’s new report, “Buying Influence Works,” details at least 13 studies showing that corporate gifts for politicians are usually followed by political gifts for corporations. For a state like New York where business executives are free to donate up to $18,000 to the Governor while bidding on state contracts, the implications of this research are dire.

While there is plenty of evidence that gifts influence politicians, there is even more showing that drug companies influence doctors. Researchers have spent three decades thoroughly documenting the pharmaceutical industry’s efforts to influence physicians. Thanks to their research, it is now well known that gifts and payments from drug companies cause doctors to prescribe more of those companies’ drugs and use more of their equipment. Studies funded by drug companies also tend to produce findings those companies like.

Drug manufacturers market their products to doctors through a process known as “detailing.” Drug company representatives go to the doctor’s office and bring some sandwiches for the doctor and her entire staff. As the doctor eats her sandwich, the representative explains the medication (or artificial knee, hearing aid, etc.) to the doctor and addresses any concerns. Now the doctor is more familiar with the product, and she has a full stomach to boot. (Though the practice is not as common as before, ‘detailers’ also sometimes give away branded swag – pens, totes, baseball hats, coffee cups – to keep their product fresh in the doctor’s mind.)

Does detailing work? Without a doubt. One study found that even a single meal from a drug company made doctors more likely to prescribe that company’s drug, and another that doctors receiving meals from drug companies prescribed that company’s drugs at rates up to 5.4 times higher than before. Reviewing the literature, Reinvent Albany could not find a single study showing no correlation between free meals for doctors and an increase in prescriptions (though still prevalent, detailing is less pervasive than it used to be).

In the research field, one of the worst actors has been Big Tobacco, which produced mountains of pro-smoking studies after concerns about cigarettes’ health impact emerged in the 1950s. Unsurprisingly, 94% of reviews by researchers affiliated with Big Tobacco produced positive findings for the industry, compared with 13% of independent reviews. When controlling for factors such as article quality or peer review, the odds that an industry-affiliated author’s study would favor Big Tobacco were 88 times higher than for non-affiliated authors. Soft drink producers and gas companies must have been taking notes.

Like politicians, many doctors and researchers deny that they’re influenced by gifts. One survey had only 8% of doctors saying small branded gifts could affect their habits. When a pharmaceutical company paid for physicians’ trip to a symposium at a luxury resort, nine of out of ten doctors said the trip would have no effect on their prescription habits (the study, of course, found otherwise). And like politicians, physicians will acknowledge the problem of pay-to-play while claiming they themselves are immune: One survey had only 39% of medical residents acknowledging that gifts could influence their prescriptions, while 84% believed other physicians are susceptible.

What does this research say about New York State? We know that the 2022 gubernatorial election was one of the most expensive in state history, and many of the largest donors had business before the state. Elected officials claim that large contributions have no bearing on state decisions, but even if that’s true, the appearance of corruption – not to mention the state’s countless pay-to-play scandals – continues to undermine the public’s faith that the government is working for the people, not wealthy donors.

New York City understands the obvious risk of pay-to-play and limits campaign contributions from people doing business with the city to $400 for mayoral candidates and $250 for City Council candidates. Embarrassingly, New York State has not passed a single law to control this kind of behavior. As of 2023, CEOs seeking contracts from the state are free to donate up to $18,000 to Governor Kathy Hochul, $10,000 to State Senators, and $6,000 to Assembly Members.

State leaders need to do much better. They can start by passing Senator Zellnor Myrie’s common-sense bill, S6247, which prohibits business executives from contributing to the Governor while seeking contracts from the state. It’s a strong first step to win back the public’s trust.

***

Tom Speaker is a policy analyst at Reinvent Albany. On Twitter @RealTomSpeaker & @ReinventAlbany.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

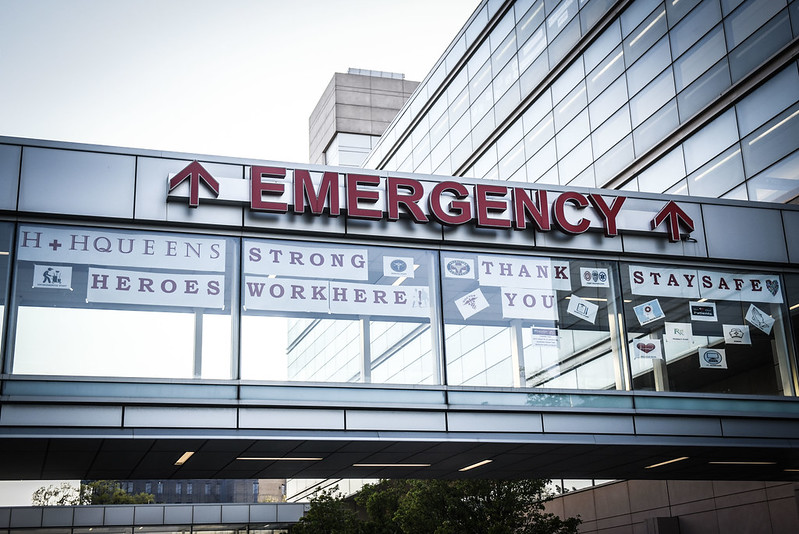

Everyone Deserves the Chance for a Life-Saving Organ Transplant If They Need It

Emergency (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Imagine that one day you wake up with a slight cough. Thinking it is a cold or allergies, you take over-the-counter cough medicine, cough drops, and even at-home remedies. Five months later, nothing seems to be working and, at your wife’s urging, you finally go to the doctor. He runs several tests and a few weeks later you get a call to come back to the office. The doctor has devastating news: “Miguel, you have Stage 4 lung cancer and you need a lung transplant.”

But there’s hope - a transplant could save your life. You are only 36 and otherwise healthy; you have a son who just turned 7, a loving and happy marriage, and so much to live for.

But you are also undocumented, so unless you can come up with nearly a million dollars, you do not qualify to be on an organ donation list and you will not get this life-saving transplant.

We’d like to think of New York as an inclusive beacon of hope and humanity, but we are failing one of our most vulnerable populations — our undocumented immigrants. We do not have a healthcare policy that covers every New Yorker.

The emergency Medicaid program covers urgent situations for undocumented immigrants, like a tracheotomy procedure or an emergency C-section, but does not cover organ transplants. Notably, however, undocumented people can donate organs. This means that although they can donate an organ to save someone else’s life, if their own life depends on a heart, lung, or kidney transplant, they are left to die.

Undocumented people should not be handed a death sentence when an organ fails simply because they lack a piece of paper and a social security number.

Miguel’s story, while heartbreaking, happens more often than it should. According to LiveOn NY, about 6,000-9,000 undocumented people in the U.S. have kidney failure requiring a life-saving transplant. Yet, only 1% of all kidney transplant recipients are

undocumented. This jarring statistic reflects only the plight of undocumented Americans in need of a kidney transplant. Thousands more need a lung, heart, liver, or other critical organ in order to survive, but are shut out because of their immigration status.

We believe that a policy dictating who lives and who dies based on immigration status is inhumane and unethical. This is why we are introducing the Humanitarian Emergency Access for Required Transplants Act, or HEART Act, which will require the State to expand healthcare coverage to include medically necessary organ transplants, regardless of immigration status. This would ensure that someone like Miguel can be placed on the transplant list and be covered for surgery, post-medical care, and prescription drugs.

Our legislation is not without precedent. In 2014, Illinois passed a similar bill into law that expanded public health coverage for emergency kidney transplants for undocumented immigrants. Although this is a step in the right direction, we must go further in New York and cover the care needed for the transplant of any organ where a person’s life is at risk, regardless of immigration status. Our undocumented neighbors must be recognized and treated like New Yorkers, and their survival should not depend on their immigration status.

***

Assemblymember Catalina Cruz represents parts of Queens. State Senator Nathalia Fernandez represents parts of the Bronx. On Twitter @CatalinaCruzNY & @Fernandez4NY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.