Letter to the Editor: Getting the Facts Right on the Governor's Budget

Director of State Operations Jim Malatras, the author (photo: Governor's Office)

To the Editor:

Re: "Proposed CUNY Cuts Threaten the University's Timeless Mission" that ran on March 16.

It's important we separate fact from fiction for your readers. As we always have, the Governor's budget fully funds CUNY at a total of $1.6 billion. Any statement to the contrary is simply false or a direct attempt to play politics and mislead the public.

Governor Cuomo recognizes the importance of public higher education which is why we continue to make significant investments in CUNY. We want to ensure academic success and equality of opportunity for not just some, but all students. Yet the out of control administrative costs at CUNY continue to threaten this very mission. Consider this: The cost of administrative expenses today at CUNY is $4,634 per student or two times the average cost of what others pay in states like California, Massachusetts and Florida. These ballooning administrative costs come at the expense of students and faculty – and that is plain wrong.

CUNY must find ways to share services, reduce overhead costs and streamline back office functions. To guide this process, the state will appoint a management organization expert to restructure administrative office functions. This expert will be tasked with conducting a comprehensive review of CUNY and presenting a plan ahead of next year's budget.

Through improved fiscal management and smart restructuring, CUNY will be able to find cost savings, look for shared services with SUNY, and ultimately direct more money to the students, classrooms and faculty who need it most. This is a plan we can all get behind.

Sincerely,

Jim Malatras

Director of State Operations for Governor Andrew M. Cuomo

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

CUNY Faculty’s Lost Decade & The Risk Ahead

PSC CUNY rally in Albany (photo: Emma Powell)

The faculty at the City University of New York has lost a decade. Salaries at CUNY have been frozen since the October 2010 expiration of our contract and even before that they failed to keep pace with inflation. In 2015, assistant and associate professors at the top salary step earned 92% in real terms of what they earned in 2006. Full professors at the top step did slightly better, taking home just under 96% of their 2006 salaries.

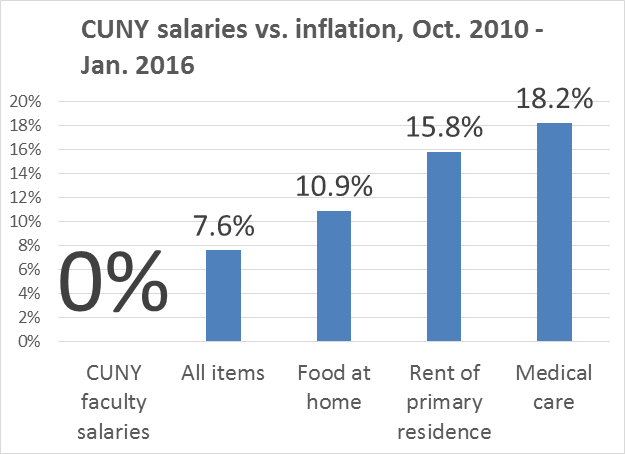

Since the contract expired, living costs in New York have risen 7.6%. Food is up 10.9%, rent 15.8%, and medical care 18.2%. Tenured full professors like me feel this on a daily basis as we struggle to balance our families’ budgets. But we’re the lucky ones.

Adjunct faculty do much of the heavy lifting at CUNY, teaching more than half of all classes, and for salaries that can be less than $3,000 per course, with little job security. In return for this paltry wage, they run classes, grade papers, and hold office hours for students. The adjuncts are the sorriest victims of the salary freeze, with many commuting frantically from one campus to another — from the Bronx to Staten Island — in an exhausting struggle to survive and to preserve a toehold in the academy and a professional identity. No wonder CUNY campuses are plastered with posters decrying “adjunct poverty.”

Students too suffer from budget cuts. Fewer courses are offered in their majors, lengthening time-to-degree. Adjuncts may not have a base at any campus and are often unavailable to meet with students or to write recommendations needed for graduate school applications. Regular faculty have to perform tasks that elsewhere are assigned to support staff, such as shopping for food for student receptions or entering course registrations in the unwieldy CUNYFirst computer. This means they have less time to advise students or to write grants that bring CUNY much-needed overhead.

CUNY has been the great equalizer, fueling upward mobility for generations of New Yorkers. Today its 24 campuses enroll 275,000 degree students and another 247,000 continuing students — some 6% of the city’s population. CUNY rightfully boasts that 40% of undergraduates were born abroad, 44% are first-generation Americans, and 42% are the first generation college students. More than half come from households earning less than $30,000 a year. Eight out of ten Latino and African-American undergraduates in the city go to CUNY schools.

CUNY remains a pillar of New York’s economy. It grants more than one-third of business degrees awarded by New York City institutions and trains one-third of the city’s teachers and many of the nurses and technicians in local hospitals. In a city where luxury condos and billionaire towers sprout like mushrooms, CUNY’s $2.7 billion capital program accounts for 20% of total construction, generating 14,000 jobs. Students at 300 high schools take courses through CUNY’s College Now program.

Why does a university that makes such an immense contribution to the city freeze its faculty pay? After five years of negotiations, management made its first salary proposal, offering three years of retroactive zero percent increases, subsequent hikes totaling 6%, and an expiration date of October 2016, a mere eight months from now. The union rejected this below-inflation “raise.”

CUNY Chancellor James Milliken and several CUNY college presidents have made tepid declarations in favor of resolving the standoff. The real obstacle is in Albany, where Governor Andrew Cuomo’s unremitting hostility to teachers’ unions extends to CUNY faculty and workers.

In 2011, Cuomo launched SUNY 2020, a program of challenge grants for capital projects and policies he argued would lead to instructional innovation and hiring at all the state’s public universities, including CUNY. The plan required that students pay $300 more each year for five years and pledged that the state wouldn’t reduce support for CUNY. Legislators voted for the hikes believing they would generate revenue to improve academic and student-support services at CUNY. Since 2012, however, the state — the source of most of CUNY’s budget — has failed to cover cost increases for rent, utilities, equipment, fringe benefits and contractual salary steps.

State revenues rose 5.6% in 2015, but in December Cuomo vetoed a bill that would have required the state to fund such increases. In January, he signed an executive action raising the minimum wage for SUNY workers to $15 an hour, but excluded state workers at CUNY. Also in January, the governor tried to shift $485 million of CUNY’s budget from the state to the city. Currently, the city funds about 30% of CUNY community colleges and the state funds CUNY senior colleges, an arrangement in place since the mid-1970s.

To Cuomo’s credit, his 2017 proposed budget includes $240 million for agreements with CUNY unions. But the $240 million is contingent on the $485 million cut in state funding. Even if the money for retroactive pay survives in the Legislature, the amount is insufficient to restore adequate salaries for faculty and other CUNY workers.

CUNY is used to crisis and austerity, with a $51 million shortfall last year and across-the-board cuts now of 3% at senior colleges. Per pupil funding is 17.4% below 2008 in inflation-adjusted terms. Top administrators’ salaries continue to climb, so the budget is balanced on the backs of faculty, workers, and students, who pay rising tuition for an education that is ever harder to deliver.

This is penny-wise and pound-foolish. CUNY’s 6,700 full-time faculty members include world-renowned experts in every field. Each year they win millions of dollars in grants, author thousands of scientific papers, and mentor new generations of informed citizens. Many depart for better jobs elsewhere. Those who remain work more years at top salary steps than they otherwise would simply to accumulate enough retirement savings. It is increasingly difficult to recruit scholars to the lowest-paid faculty in one of the country’s highest cost-of-living regions, and it is usually impossible to replace professors who leave or retire.

The neglect of CUNY exacerbates inequality, deprives hundreds of thousands of students the education they deserve, and lessens New York’s competitiveness in the global economy. New Yorkers need to decide if they want to invest in the future of their city and, if so, make sure that our elected leaders know.

***

Marc Edelman is professor of anthropology at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Proposed CUNY Cuts Threaten the University's Timeless Mission

At the CUNY Grad Center (photo via @GC_CUNY)

Roused from the self-imposed seclusion of doctoral dissertation data entry, I was awakened by attention to the recently-proposed drastic budget reduction to our nation's largest urban university system – the City University of New York (CUNY). These are cuts that simply cannot be allowed to go through and this is an issue that affects all of New York, not just the faculty, students, and staff of CUNY.

Public funding for higher education in New York City is the lifeline for many, offering a college education that is accessible, affordable, and high quality. The pending state budget, proposed by Governor Cuomo, includes a $485 million cut from the CUNY operating budget. Such a cut is a direct threat to CUNY, where so many who would not otherwise have access public higher education can actually afford to attend.

We must ensure that CUNY stays affordable.

CUNY's mission since 1847 has been "to provide education to the children of the whole people of New York City." Given financial facts and persistent economic inequality, not everyone can afford one of the highly-ranked private institutions located throughout our city. CUNY provides a high-quality education for a fraction of the cost.

I've been a nurse for 27 years and have two bachelor's and two master's degrees, all from private institutions. A doctoral degree was the next logical step. I chose to come to the Nursing Science Program at The CUNY Graduate Center to pursue my PhD after exploring my options in the tristate area. The Graduate Center is the hub for PhD and Masters programs at CUNY. The very reasonable price of tuition was attractive, but after looking at the options available in the city, what appealed to me most was the expertise and experience of the nursing faculty in the program.

While my story is not indicative of the large majority of CUNY students, it is not unique for the reasons that I chose CUNY and the positives of my experience there.

Composed of scholars and researchers from the three senior CUNY colleges with nursing programs (Hunter, Lehman, and the College of Staten Island), I was enticed, then offered the opportunity to matriculate and to be able to learn, develop, and grow with them. Now in my fourth and hopefully final year with my dissertation nearly done, I regularly reflect on the quality of the program. Never more so than when I see that CUNY funding is in jeopardy.

I have gained so much, not just in perspective, but in the opportunities to have independent thought and pursue deeper expertise. This ability to explore and develop independent scholarly thought is so important, and a unique attribute of the CUNY experience - one different from other local doctoral nursing programs.

The past four years have been a wonderful experience here at the Graduate Center in the PhD in Nursing Science Program, a personal evolution into the world of nursing scholarship, research, and academia.

Cutting funding to the CUNY system and the Graduate Center would be a tragedy of epic proportions for the educational possibilities of future nurses and those who would become nursing faculty so desperately needed, especially in the 12 CUNY nursing programs in our five boroughs.

We can't allow Governor Cuomo and state legislators to eviscerate quality, affordable educational programs throughout CUNY, especially at the Graduate Center I call home. All New Yorkers must let them know that New York City needs the CUNY higher education programs; a $485 million cut in the budget is a direct threat to affordable and accessible higher education for the "children of the whole people."

***

by Randy E. Gross MS, RN, NP, CNS, WHNP-BC, ACNS-BC, AOCNP®, AOCNS®

Nurse Practitioner & Clinical Nurse Specialist

Doctoral Candidate – PhD in Nursing Science Program, CUNY Graduate Center

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Right Model to Follow for Diversity at Specialized High Schools

Student debaters (photo: @NYCschools)

Last week, 5,000 eighth graders got the exciting news that they were offered admission to one of the city's eight test-in Specialized High Schools, which offer a quality public school education unmatched in the country. But while the vast majority come from poor, working class and immigrant families, as has always been the case, once again far too few come from the black and Latino communities.

Black and Latino students comprise a large majority in the city's public school system and should be better represented among those offered admission to its top high schools. Unfortunately, this year about 500 fewer black and Latino students sat for the test compared to last year, and the percentage of these students offered admission declined as well.

The school system, like the city it serves, is heavily segregated, but this lack of racial and ethnic diversity in our test-in schools is unacceptable for many reasons. Still, doing away with the test as the sole criteria for deciding admission and switching to inherently subjective multiple criteria would do little to ameliorate the imbalance and could make it worse according to last year's study by NYU's Institute for Education and Social Policy.

The city must instead invest the resources – both financial and intellectual – and take proactive steps on both a long-term and an immediate basis in order to diversify admissions to our best schools.

A program of enriched educational opportunity must be instituted in every neighborhood to permit all children to have a fair chance of success on the test and in life. Gifted and Talented Programs must exist in every district. Enriched education, especially in math and English language courses, must be available in every middle school in the city. When 53 percent of the students at test-in schools come from only 15 percent of middle schools, the fundamental answer to the problem of underrepresentation is clear.

Immediate actions must be taken to increase the numbers of students from underrepresented communities sitting for the test. And, increased attention must be paid to better preparing underrepresented students to do well enough on the test to gain admission. There is no fixed passing grade on the test. "Passing" is simply a function of scoring high enough to rank among the 5,000 highest scoring students to qualify for admission to one of the schools.

The Brooklyn Tech Alumni Foundation, which I head, with the support of National Grid, has worked with Brooklyn Tech to run an innovative pilot STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) Pipeline program for the past three years that reaches out to underrepresented middle schools, identifies children of promise and provides them with accelerated coursework and test prep. The program starts with rising seventh graders and offers them an intensive two year experience with classes during the summers and on Saturdays during the school year.

We have had good success during the first two years that students in the program have sat for the test. This year, students received offers from Brooklyn Tech, Stuyvesant, and Brooklyn Latin, all specialized schools. Half of last year's students in the program – and nearly two-thirds this year – offered admission to Tech are black or Latino.

We are encouraged by the support for diversity at specialized high schools shown by Albany legislators in both chambers who are proposing dedicating funds to create similar pipeline programs in every test-in school. This would cost less than $1.3 million a year, or $2.5 million over two years, and enable all eight specialized high schools to run outreach and test preparation programs in underrepresented middle schools throughout the city.

While Mayor de Blasio is committed to combatting educational and economic inequality, it is still the case that a child's chances of educational success are closely correlated to where he or she grows up. Because test-in schools should serve students from every neighborhood, there is a special obligation to give all promising students tools to succeed.

The answer is not to do away with an admissions test, but to make that promise of social equality real by committing resources and intellectual firepower so that every academically promising child, regardless of their neighborhood, has a fair chance of succeeding on the test, and beyond.

***

Larry Cary is president of the Brooklyn Tech Alumni Foundation.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

A Good Investment: Supporting New York's Immigrant Communities

Steven Choi, the author (photo via NYC DOE)

New York prides itself on being a gateway of opportunity, a place where people from across the world come to build their businesses, send their children to school, and provide for their families. With more than four million immigrants in New York, these newcomers make tremendous, vital economic, social, and cultural contributions to the Empire State.

And yet there is an enormous amount that our state - led by our elected officials - can do to support our newest New Yorkers move up the economic ladder. That’s why on Thursday, March 10, the New York Immigration Coalition is holding a statewide advocacy day, all the way from Buffalo to Brentwood, to commit to NYIC’s 2016 “Immigrant Blueprint for New York” – the framework for a comprehensive, long-term plan for the state to improve outcomes for immigrant communities and help be a national leader in immigration.

On Thursday, we'll meet with 38 legislators across New York - in Buffalo, Rochester, the Hudson Valley, New York City, and Long Island - to emphasize the needs of their communities.

Our “Blueprint” includes five major pillars for how to achieve immigrant prosperity:

Strengthen integration efforts for New Americans by providing adult education programming for immigrants that need them, and ensuring that limited-English-proficient speakers are able to access government services;

Address the persistent achievement gap for immigrant students and English Language Learners by ensuring tuition equity on the college level, creating multiple pathways to a high school diploma, reducing the required number of Regents exams, and investing in career and technical education;

Provide access to healthcare for immigrants who are excluded from coverage by federal law, and improving access, coverage, and care for immigrants who are eligible to participate in New York’s health exchange;

Advance immigrant justice and uphold due process through ensuring access to affordable and reliable legal services, as well as limiting intrusive and unlawful collaboration between local and state law enforcement and immigration officials to improve trust between communities and law enforcement;

Protect workers’ rights for New York’s most vulnerable, including farmworkers and other low-wage workers exploited by unscrupulous employers, and by meeting basic needs such as including access to driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants who play critical roles in our economy yet lack tremendous barriers around transportation access.

These strategic steps are not pie-in-the-sky. They are concrete and achievable, and will do wonders for New York’s economic growth - catapulting New York even further as a leader in successful immigrant integration. This March 10, our message is simple: By supporting immigrant communities, we are investing in New York - and we call on our elected officials to use this blueprint to make sure we secure New York’s present and future as the greatest state in the union.

***

Steven Choi is the executive director of the New York Immigration Coalition. On Twitter @SteveChoiNYIC & @thenyic.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Addressing NYC's School Overcrowding Crisis

Protesting school overcrowding in Queens

All parents in New York City deserve the peace of mind that their children will be able to attend a school where they can thrive and grow. Unfortunately, following years of neglect from the Bloomberg administration, our city's school system is plagued by school overcrowding and excessive class sizes, where hundreds of thousands of our children simply don't have adequate space to learn.

With education a top priority for the city, it's critical that our leaders take strong action to address the chronic underfunding of our city's school infrastructure. Key to addressing this issue is investing sufficient capital resources in the city budget, as well as improving the current school planning process, which is broken.

Recently, we've had some good news. When the city Department of Education (DOE) released its school capital plan, it included a commitment from Mayor de Blasio to invest nearly $900 million in additional resources to build more school seats. In the same plan, the DOE raised its needs assessment to 83,000 additional seats, given enrollment projections and existing overcrowding. This is closer to the 100,000-seat figure that Class Size Matters estimated in its recent report, "Space Crunch." Together, these two adjustments are a welcome acknowledgement of the crisis in school overcrowding, and we applaud them.

But more should be done. The number of new seats in the capital plan is 49,000—only about 59 percent of the DOE's own admitted need—and New York City's population is growing faster than any other large city in the nation. The mayor is now urging the City Council to adopt rezoning plans to accelerate the construction of thousands of new affordable and market-rate housing units, which will increase pressure on our school system. At this critical moment, the city has a real opportunity to address housing and education together.

Right now, more than half a million students are crammed into over-utilized schools, according to DOE data. In many cases, this means excessive class sizes of 30 or more, a loss of art, music, or science rooms, and a lack of dedicated spaces for students to receive counseling or mandated special education services – no less the wraparound services inherent in the community school model.

According to the analysis in a recent report by Make the Road New York—"Where's My Seat?"—immigrant communities have especially egregious overcrowding problems and even greater unmet needs in the DOE capital plan. In many of the schools in these neighborhoods, children are forced to eat their lunch as early as 10 a.m. or are bused to schools far away from their homes. Many do not have adequate opportunity for physical education because there is not enough space in their gyms.

We need to build, lease, and expand more schools. At least the 83,000 seats that the DOE projects are necessary. In addition, the process of school planning and siting must be made more efficient. There are many communities, like Sunset Park, which have suffered from extreme overcrowding for a decade or more, even though funding to build more schools in the neighborhood has existed in the capital plan, because the School Construction Agency has not been able to site a single one.

According to the DOE, only 15 percent of the school seats needed by 2019 have sites identified and are in the process of being designed. In seven districts, that percentage is zero. The city will fall even further behind in creating seats if the mayor's rezoning proposals are adopted, unless much more is done to build and site schools. A recent Environmental Impact Statement for the East New York rezoning proposal found it would exacerbate school overcrowding, and, along with other changes, drive high school overcrowding in the borough to 109 percent of capacity. Yet the DOE capital plan does not include a single Brooklyn high school to be built.

That is why we are urging the City Council, along with the mayor, to create a commission or task force of experts and stakeholder groups, to propose reforms to the school planning process, so that schools must be built along with housing, instead of decades afterwards. Among the issues to be considered would be reforms to the zoning process, including whether the threshold to consider the need for a new school should be lowered – especially when the schools are already overcrowded; whether the formula used by City Planning to estimate the impact of new housing on schools needs to be updated; whether the city should require impact fees from developers and/or use eminent domain more frequently; and how the trends in lost seats, utilization rates, and enrollment could be made more transparent and more accurate through regular reporting by the DOE.

As Mayor de Blasio repeated in his recent State of the City speech, the goal across our city must be to ensure that neighborhoods thrive. There cannot be successful neighborhoods unless there are schools with enough space for the children in every community across the city to learn and prosper. It's time to invest all the necessary resources and improve the school planning process to ensure the bright future that all of our children deserve.

***

Leonie Haimson is the Executive Director of Class Size Matters. Javier H. Valdés is the Co-Executive Director of Make the Road New York. On Twitter: @leoniehaimson @javierhvaldes.

As Teddy Roosevelt Did, 2016 Candidates Drag the Supreme Court Into Presidential Politics

The Supreme Court (Carol Highsmith, via Library of Congress)

The Supreme Court is being drawn against its will into the chaotic 2016 presidential campaign.

Republicans Donald Trump and Ted Cruz dislike the court's decisions affirming Obamacare and gay marriage. Democrats Hillary Clinton and Bernard Sanders object to its Citizens United campaign finance decision. Senate Republicans are threatening to block President Obama's nomination to replace recently deceased justice Antonin Scalia, alleging the appointment would be better left to the next president (a Republican, they hope). Donald Trump was (probably) kidding when he said his sister, Federal Court of Appeals Judge Marianne Trump Barry, would make a credible Supreme Court nominee.

In a recent speech, Chief Justice John Roberts lamented that partisan extremism is damaging the public's perception of the court as an unbiased interpreter of the law that is above politics. People too often accuse the court of taking sides in an issue but all it is doing is objectively judging constitutional merits, he said. "We have no policy views on the matter at all," Roberts insisted.

But dragging the court into presidential politics has a long history.

Theodore Roosevelt was the first presidential candidate to assail the court, during the 1912 contest. TR, president 1901-1909, was attempting to gain the Republican presidential nomination and oust the man who had succeeded him, William H. Taft.

On a speech-making tour in the West in the fall of 1910, he attacked big business. The nation was in the midst of a struggle "between the men who possess more than they have earned and the men who have earned more than they possess."

He lambasted the federal courts for lagging behind the times and criticized them for "a series of negative decisions to create a sphere in which neither nation nor state has effective control."

He cited the 1905 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lochner vs. New York as a prime example. By a vote of 5 to 4, the court had overturned a New York law regulating the hours and working conditions of bakeshop employees on the basis that it violated the provision of the 14th amendment to the Constitution that no state shall "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." That amendment, passed in 1868, had been intended to protect the civil rights of newly-liberated African-Americans. But the courts had stretched it so that that "liberty of contract" included the right of employers and employees to work for whatever wages and hours both parties agreed to.

The courts had used this broad interpretation of the amendment to strike down a number of state regulatory statutes. TR knew the Lochner case well. As governor of New York, 1899-1901, he had enforced the bakeshop regulations. As president, he had watched the case come up through the New York State court system. In 1904, the State Court of Appeals validated the law in a decision written by its Chief Judge, Alton B. Parker, who later that same year secured the Democratic presidential nomination and ran unsuccessfully against TR. He followed the case in the U.S. Supreme Court the next year and read the decision, which was written by still another New Yorker, Justice Rufus Peckham. But the president made no public comment on it.

Roosevelt, in 1910, however, declared that the Lochner decision had been particularly egregious because it had ignored the problems that the bakeshop law was intended to address and exercised "the negative power of not permitting the abuse to be remedied." The court had demonstrated that it was "against popular rights" by asserting that "men must not be deprived of their 'liberty' to work under unhealthy conditions....Such decisions, arbitrarily and irresponsibly limiting the power of the people are of course fundamentally hostile to every species of real popular government."

Newspaper editorials and political leaders in both parties expressed outrage at the attack on the court.

Roosevelt, undeterred, went on to suggest something even more extreme, allowing voters to recall judges. He advanced a campaign platform filled with liberal proposals, including federal regulation of corporations, a national health service, and insurance for the elderly (similar to Social Security two decades later). His attack on the judiciary seemed menacing and his other proposals were ahead of their time. TR "startled all thoughtful men and women and impressed them with the frightful danger which lies in his political ascendancy," said the New York Times. Roosevelt failed to get the Republican nomination and went on to found a new party, the Progressive Party, but was decisively beaten in the 1912 presidential contest.

The Lochner decision was influential and was often cited by the courts in striking down state and federal regulatory statutes until 1937, when it was in effect repudiated in the decision of West Coast Hotel vs. Parrish.

Supreme Court Justice Rufus Peckham, in his opinion in the 1905 Lochner case, insisted, a little defensively, that "this is not a question of substituting the judgment of the court for that of the legislature." But TR lambasted the court in 1910 for doing just that. John Roberts, at his confirmation hearing to be Chief Justice in 2005, pointedly disagreed with Peckham's assertion a century earlier. Roberts said that the majority in the Lochner decision was "not interpreting the law, they're making the law...substituting their judgment on a policy matter for what the legislature had said."

Roberts was probably right. Theodore Roosevelt would certainly agree.

But Roberts probably shouldn't be surprised, then, that 2016 presidential candidates are criticizing his court, following the precedent set by TR back in 1910.

They believe the court's objectivity has been tarnished.

And, also like TR, they think they see an easy opportunity to score political points.

***

Dr. Bruce W. Dearstyne's latest book is The Spirit of New York: Defining Events in the Empire State's History, published in 2015 by SUNY Press.

Will the Democrats' Fresh Entitlements Lift Poor Families?

De Blasio on a school visit (photo: Ed Reed, Mayoral Photography Office)

Circle time at preschool teaches much about civility and unity, how best to contribute to a pint-size society.

So when little Lela whispered from the corner, "I'm ready to come back," teacher Katie Wassel in Washington Heights figured lesson learned, the 4-year-old rejoined a tight crescent of fidgeting peers seated on a colorful rug. You can't elbow your neighbor at circle time.

Hillary Clinton draws a wide and inclusive circle all her own, pitching fresh entitlements to ease the financial angst of families – parental leave, universal pre-kindergarten, tuition-free community college – and nudged leftward by young voters, many women, Senator Bernie Sanders, and diehards who continue to 'Feel the Bern.'

Fiscal conservatives warn of ballooning costs for existing social guarantees. But a thornier question confronts Democrats: Might they inadvertently worsen inequality, rather than close disparities between poor and well-heeled families?

Take Mayor Bill de Blasio – poster boy for novel entitlements – and his well-meaning spread of free pre-K for all families, no matter how rich or poor.

His original yarn was a tale of two disparate cities. "The best and the brightest are born in every neighborhood," he declared after winning election, seeking to narrow early gaps in children's learning. A half-century of research findings does show that quality preschool can lift impoverished children.

But Mr. de Blasio pushed for a universal benefit, crawling out on a thin policy limb, ignoring three national studies, including my own with Stanford economist Susanna Loeb, that discern just minuscule and fading effects of pre-K for children from better-off families.

Why? Because most middle-class parents – two-thirds of whom nationwide already enjoy access to pre-K – offer important nurturance at home as well. And if the mayor's pre-K proves to elevate all kids, how would this narrow gaps in children's early growth?

The mayor's fuzzy logic reveals a deeper dilemma for Mrs. Clinton and Democratic candidates: How to rekindle opportunity for the middle class, while delivering on their perennial promise to lift the poor.

White Americans have seen their earnings slip by 3 percent since the late 1990s, falling to $60,300 in mean wages last year. But total income ticked upward, thanks to middle-class tax cuts and rising aid for health care, says the Congressional Budget Office. In stark contrast, nearly 24 million children under age six live below or near the poverty line. Affordable pre-K remains out of reach for half these families.

More than 103,000 four-year-olds populate New York City and are eligible for preschool. Mr. de Blasio has added more than 38,000 full-day pre-K seats citywide, totaling more than 68,500, many in depressed parts of the city. But over 30,000 potential preschoolers remain outside any public program, two-fifths being raised in the city's poorest neighborhoods.

Entitlement hawks also teach us that one size can't fit all, especially when serving the nation's kaleidoscopic variety of families. At first Mr. de Blasio aimed to mainly enlarge the count of preschool seats in city schools, pleasing the teachers union but stirring protests from the city's 1,900 private, mostly nonprofit pre-K's, which have resisted cookie-cutter programs for over a century.

Take parents who prefer half-day pre-K, allowing quality time at home for parent and child, but who now lose their subsidy, given the mayor's insistence on full days inside classrooms. Jewish educators seek more instructional time to advance religious teaching. Charter schools last month appealed Albany's siding with the mayor that he, not charter authorizers, can regulate independent pre-K programs.

New York's experiment also reveals the risk of obsessing on what's new and shiny when regimented entitlements arrive. The mayor largely ignored existing supply, incenting middle-class parents to migrate into tuition-free preschools. This emptied up to 14,900 children from older programs, rather than widening access - what economists dub a substitution effect. "We lost two full classrooms of 4-year-olds," said Don Williams, manager of a Midtown pre-K.

President Obama and Republican governors, like Michigan's Rick Snyder, dodge the risks of unbridled entitlements, opting to expand pre-K access for poor youngsters, while easing middle-class costs via tax credits. A rising count of companies, from Netflix to Goldman Sachs, help shoulder the burden of essential human supports: from paid leave for parents nurturing a newborn to insuring security in old age.

Instead, untethered entitlements go awry when benefits tilt toward better-heeled players, say how price supports for farmers became welfare for the well-off, or when taxpayers underwrite pre-K or high-priced universities for parents who can afford to pay.

The campaign season may prompt serious debate over the future of entitlements, along with how to bolster working families. But as Mrs. Clinton and leading Democrats embrace new social guarantees, pursuing middle-class voters, they should be honest about who they aim to buoy and who they would leave behind.

***

Bruce Fuller, professor of education and public policy at Berkeley, is author of Organizing Locally (University of Chicago Press).

A Budget for Immigrant New York

photo via Make The Road New York

Growing up in Puebla, Mexico, I was raised to believe that all families, and all communities, deserve their fair share.

Since immigrating to New York, however, I've seen clearly that immigrant communities here often get far from their fair share. Immigrant communities like Woodside, Queens, where I live, too often lack the basic infrastructure and opportunities that residents need—good schools, safe and affordable housing, access to good-paying jobs, and more. We just get the short end of the stick relative to better-off neighborhoods.

As I've followed recent political debates in our state, I've learned that a lot of that has to do with the state budget. The budget, more than anything else that happens in our state each year, has an enormous bearing on shaping the priorities of our state government and determining which programs and regions will get the funding that they need. The budget determines funding for everything from education to housing to health care. And, with more and more policy decisions getting inserted into the budget in recent years as a way of getting around Albany's dysfunction, the budget is actually now the biggest policy-making vehicle in our state.

That's why, this year, my fellow members of Make the Road New York and I are calling for immigrant communities across the state to get our fair share of the state budget. In a new report that we released this week, "A Budget for Immigrant New York," we call for greater equity across the budget, so that immigrant communities can thrive as they deserve.

The report highlights 25 items, but my own story shows why three are so important.

First, we call for the state to include in its budget an increase in the minimum wage to $15 per hour as soon as possible, with indexing to inflation. As a minimum wage earner, my dream has been to improve the lives of my four children, but the wages I earn are too low for me to do that. The truth is, on my wages it is impossible to get ahead in this expensive state. Raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour for me is an issue of survival. A $15 minimum wage would mean enough food in my house at night for my family, and peace of mind that I could begin to meet all of our other needs.

Second, we call for an increase of $2.9 billion in new school aid. As a parent of four, I worry every day about my children's education, and it pains me to see them attending schools that don't have all the resources they need. Under-resourced schools like theirs are not the exception—they are the rule. We need billions of dollars in additional school aid, and it must prioritize high-needs school districts.

Third, immigrant adults need the opportunity to fully integrate themselves in their communities through adult literacy programs. I'm currently enrolled in an English class that I know will help me engage better with my children's teachers and find a better job, but too many other immigrants can't access classes because there is not enough state funding. We need $17 million in adult literacy funding in this year's budget.

On these issues and so many more, this year's budget offers an opportunity to do more for immigrant communities in desperate need. We need leaders in Albany to step up to make sure that we get our fair share.

***

Cristina Molina is a member of Make the Road New York, the largest grassroots community organization in New York offering services and organizing the immigrant community. On Twitter: @maketheroadny

Ten Days in the Life of a Police Reform Advocate

PROP volunteers, including the author (photo: @PROPNYC)

In a recent ten-day period I had experiences that taught me new things about bad NYPD practices, reinforced my cynicism about the lame way that mainstream politicians, including officials who self-identify as progressives, posture on policing issues, and strengthened my determination to press aggressively for fundamental and meaningful changes in NYPD policies. My organization, PROP - the Police Reform Organizing Project - continues to monitor NYPD practices and advocate for real change.

*On a monitoring visit to the Brooklyn criminal court -- PROP representatives and volunteers regularly observe proceedings in the arraignment parts of the city's criminal courts as a way of tracking NYPD 'broken windows' arrest practices -- I stood on a line of about 45 people waiting to pass through the metal detector. I was the only white person -- everyone else was African-American or Latino, the vast majority of whom dressed in clothes suggesting that they were members not of the well-to-do professional class, but of the low-income or working classes.

*On that morning, the Brooklyn misdemeanor arraignment part heard 34 cases, all men of color whom the police had arrested and locked up. Each of these men walked out of the courtroom, meaning essentially that no court official, including in most cases the prosecutors, considered the defendants dangerous or predatory. The charges included suspended license, theft of services (usually fare-beating), marijuana possession, disorderly conduct, and open alcohol container.

*At a meeting later that day, a fellow police reformer reported that he had recently attended a police/community meeting where neighborhood residents had a discussion with officials from the local precinct. The community members expressed concern about a recent armed robbery and asked what the police were doing about it. The officials responded by saying that they were "summonsing like crazy," meaning that police officers were issuing many criminal summonses to people in the neighborhood for representative 'broken windows' infractions/activities like being in the park after dark, littering, carrying an open alcohol container, or riding a bike on the sidewalk. Community members raised the pointed question: But what are you doing to actually investigate the crime and catch the perpetrators?

*At a meeting with a journalist and me, a police officer who is considering coming forward to publicize the ill effects of the NYPD's quota system on officers and New Yorkers alike, reported on the following matters: under the pressure to "make their numbers" each month, some officers working in a precinct with a cemetery within its borders will issue what are known as "cemetery summonses," meaning that they will enter the graveyard and write up tickets with the names of dead people that that they find on the tombstones. Some precincts - those that serve white well-to-do areas, for example - have no quotas. One of the first questions that an officer new to an inner-city precinct asks is: "What is the number?" And, again under the pressure of the quota system, some officers will for most of the month ignore a neighborhood "hot spot," a place where crime such as drug dealing or prostitution takes place in the open, and if they have not met their quotas, will round up the people at those sites at month's end.

*A PROP volunteer, a teacher who instructs students at night classes in the City College system, reported the following stories that he heard during a class discussion about discriminatory NYPD practices: two students of color, both women - one African-American and the other Latina - recounted unsettling encounters with officers on select buses in the Bronx. In one case the woman couldn't at first find the receipt when the officer approached her, so the officer began writing up the summons; she did eventually find it, but when she displayed it, the officer said that it was too late, that he had already filled out the ticket; she has refused to pay the fine and plans to fight the ticket. In the other case, the woman made a mistake in pressing the buttons of the ticket machine at the bus stop and ended up with 2 tickets for handicapped people which totaled the same amount, $2.50, as a regular ticket; the officer still issued a summons and, in this case, rather than take the time that she couldn't afford to oppose the summons, the woman paid the fine.

*PROP released an analysis of the NYPD's misdemeanor arrest practices for 2015, revealing that 87 percent of those arrests involved people of color compared to 85.8 percent in 2013 and 86.5 percent in 2014. To demonstrate the blatant racism associated with these practices, we focused on some specific kinds of arrests including theft of services, or fare-beating, which at 29,198 was the NYPD's most numerous arrest category for last year. Fully 92 percent involved people of color - in fact, in our year-and-a-half of court-monitoring work, we have observed only a handful of white defendants charged with theft of services. Spokespeople for City Hall and the Police Department made statements in response focused on safety on the subways, but that did not address the extraordinary racial imbalance reflected in the numbers that PROP had spotlighted.

Despite these numbers and accounts that demonstrate the undeniable racial bias and deep injustices involved in the NYPD's current application of quota-driven 'broken windows' policing, our city's leading politicians, including Mayor Bill de Blasio and City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, announce and occasionally enact the softest kind of modifications that do nothing to fundamentally change or end the NYPD's abusive and discriminatory practices.

Out of political considerations - it would be too risky to promote the fundamental police reforms needed - they have effectively abandoned one of their main constituencies: low-income New Yorkers of color, leaving them to the harsh treatment and societal marginalization that result from the practices and policies of the NYPD and the city's criminal justice system.

It is up to us police reformers and other concerned New Yorkers to keep hammering away at these issues. Despite our frustration and disappointment of the moment, we know that silence will kill all hope of achieving our shared goal of a fair, safe, and inclusive city for all New Yorkers.

***

Bob Gangi is Director of the Police Reform Organizing Project. On Twitter @PROPNYC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Peter Liang’s Conviction Shouldn't Be Dividing the Asian American Community

(Diana Robinson/Mayoral Photography Office)

Rookie New York Police Department Officer Peter Liang was on patrol in an East New York housing project in November 2014 when a bullet from his gun ricocheted off a wall and killed 28-year-old Akai Gurley, a black man. The uproar over Gurley’s death culminated in Liang’s conviction of second-degree manslaughter this month, provoking an unusually strong but misguided reaction from the Asian American community.

The anger boils down to the notion that Liang was the subject of selective prosecution. In other words, he did not go through the same judicial process as the white officers who have gotten away with killing young black men. Framing Liang’s conviction in this context is not only insincere but misleading. If we were to follow this trend of unaccountability, we would essentially call for Liang’s freedom—something that would run counter to the concept of justice and, more importantly, devalue Gurley’s life.

We need to consider whether this incident actually illustrates discrimination against Asian Americans or reinforces the reality that white police officers are not being held responsible for the loss of black lives. If the goal of the recent rallies across the nation is to indeed raise awareness of the latter problem, then opponents of Liang’s conviction should have organized long before his trial. Demonstrating now, as New York Times Magazine contributor Jay Caspian Kang succinctly puts it, “deforms the stated intentions.” It also comes across as self-serving rather than a righteous stand against injustice.

I say this in light of the more evident challenges that Asian Americans face. We are unfairly pitted against our black and Latino peers as the “model minority” and perceived as perpetual foreigners. The list of such bigoted behavior against Asian Americans is well-documented. Sadly, however, it has also prompted an unnecessary victim mentality—one that now suggests that Liang is an example of how Asian Americans, like black people, suffer from a miscarriage of justice.

Our status as a minority does not automatically give us the right to share in the experience of others who are more heavily affected, as Asia Times contributor George Koo would have us believe. The truth is that Asian Americans, as a whole, are far less likely than blacks to be targeted by law enforcement or incarcerated. We cannot liken the severity of Liang’s conviction to the death of Eric Garner or Michael Brown, whose passings sparked serious conversations on our country’s execution of criminal justice. We cannot say that Liang and Gurley are both victims. Liang killed a black male; Gurley was a black male who was killed.

When I think of incidents in which our system has actually betrayed Asians and Asian Americans, I am immediately reminded of Vincent Chin, whose deadly beating in 1982 by white auto worker Ronald Ebens and his stepson resulted in just a penalty of three years of probation and a fine.

I think of Cau Bich Tran, whose shooting by Officer Chad Marshall in 2003 failed to lead to an indictment. I remember the death of Fong Lee, whose family burst into tears after Officer Jason Andersen was acquitted of using excessive force back in 2006. These are explicit instances in which I question whether Asian lives matter too.

To somehow portray Liang as the unfair target of what was ultimately a standard legal procedure is a disservice to Gurley, Garner, Brown, Chin, Tran, and Lee. We cannot choose to suddenly designate ourselves as a marginalized minority when the merit of the facts in Liang’s case clearly outweigh the connection we have to him as Asian Americans. Liang and I are of the same community, but his particular crusade is not mine.

***

Justin Chan is an editorial production associate at The New Yorker. He most recently served as a columnist at Mic, where he explored the media's emasculation of Asian American men and the rise in spending among Asian American youth. You can follow him on Twitter @jchan1109.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.