Max & Murphy Podcast: Republican Attorney General Nominee Keith Wofford

Ben Max, left, of Gotham Gazette, and Jarrett Murphy, right, of City Limits

October 10, 2018 - Max & Murphy Podcast: Republican Attorney General Nominee Keith Wofford

Keith Wofford, the Republican nominee for Attorney General, joined the show to discuss his platform for assuming the role of the state's chief legal officer, outlining a vision very different from his main rival, Democratic nominee Letitia James. A first-time candidate for office, Wofford explained his resume and his top priorities for the job of Attorney General.

Keith Wofford, the Republican nominee for Attorney General, joined the show to discuss his platform for assuming the role of the state's chief legal officer, outlining a vision very different from his main rival, Democratic nominee Letitia James. A first-time candidate for office, Wofford explained his resume and his top priorities for the job of Attorney General.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think -- we're on Twitter @TweetBenMax and @JarrettMurphy. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Max & Murphy Podcast: Larry Sharpe, Libertarian nominee for Governor

Ben Max, left, of Gotham Gazette, and Jarrett Murphy, right, of City Limits

October 10, 2018 - Max & Murphy Podcast: Larry Sharpe, Libertarian nominee for Governor

Larry Sharpe, the Libertarian nominee for Governor, joined the show do discuss his platform, which includes decentralizing government, slashing the state budget, and overhauling the state's education system. He discussed his views on gun control, funding the MTA, and more.

Larry Sharpe, the Libertarian nominee for Governor, joined the show do discuss his platform, which includes decentralizing government, slashing the state budget, and overhauling the state's education system. He discussed his views on gun control, funding the MTA, and more.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think -- we're on Twitter @TweetBenMax and @JarrettMurphy. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Comptroller Candidates Debate Powers and Responsibilities of State's Top Fiscal Officer

Candidates DiNapoli, Dunlea, Gallaudet, Trichter (l-r) during their first debate

New York State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, a Democrat running for reelection as the state’s top fiscal officer, faced his three challengers on Tuesday in the first debate of the general election, hosted by Manhattan Neighborhood Network.

The four candidates offered their views on the powers and role of the state comptroller, charged with managing the state’s $207 billion public pension fund, overseeing state and local spending, auditing state contracts and the finances of hundreds of state agencies and authorities, and ensuring that New York’s debt obligations and funding needs are carefully calibrated to current and future revenue.

DiNapoli, who first took office in 2007 following the resignation of his predecessor, Alan Hevesi, amid scandal, was elected by voters in 2010 and 2014. He went unopposed in this year’s primary and is running with nominations from the Democratic Party, Working Families Party, Reform Party, Women’s Equality Party, and Independence Party -- his name will appear on all five lines on the November 6 ballot. His opponents include the Republican nominee Jonathan Trichter, who also has the Conservative Party ballot line; the Green Party’s Mark Dunlea; and Cruger Gallaudet, a Libertarian.

The debate, just over an hour long and moderated by Gotham Gazette Executive Editor Ben Max, will air on MNN and be posted to its YouTube channel on Sunday night.

It mostly saw DiNapoli defend his record against criticism from Trichter, a previously registered Democrat who switched his party registration to Republican and received the necessary Wilson-Pakula certificate to run on the party’s line this fall. The back-and-forth arguments between the two largely centered in wonky fiscal issues, some of which it would take an unaffiliated expert on state finances and constitutional powers to wade through (Gotham Gazette is working on a detailed fact check).

DiNapoli stressed that he has been a prudent steward of the pension fund and a strong, independent voice for sound fiscal practices, promoting reform and providing a steady hand both for an office previously mired in scandal and a state going through the Great Recession and its aftermath. Trichter alleged that DiNapoli has been a subpar investment manager and not a forceful enough voice for change in state budget and other fiscal practices where the comptroller has oversight.

Dunlea spent his time reliably offering up suggestions to divest the state pension from the fossil fuel industry and pushing for more accountability and transparency in the fiscal management of state authorities. Gallaudet had little to offer in terms of specific ideas, and instead repeatedly pleaded to viewers to reject the “duopoly” of the Democratic and Republican parties and to cast a ballot for the Libertarian statewide ticket. He said the comptroller race would be a good place for voters to use a “split-ticket,” presumably where they would select a Democrat (Governor Andrew Cuomo) or Republican (Marc Molinaro) in the governor’s race, in order to send a message, but also repeatedly said voters should examine Libertarian gubernatorial candidate Larry Sharpe.

DiNapoli States His Case and Defends His Record

“It’s really the office that promotes accountability and transparency in state government and local government as well,” said DiNapoli, explaining the role in his opening remarks. He also took a dig at Trichter for switching to the Republican Party, the party of President Donald Trump, and for claiming to be a financial professional though he has worked as a political operative in the past. Some of DiNapoli’s responses to Trichter, who attacked the incumbent in nearly every answer he gave, were as aggressive as most who’ve followed the typically mild-mannered comptroller’s career have heard from him.

“Unlike Jon, I have my values as a Democrat and have stuck with them all my life...If you have to sell yourself to get the nomination, I don’t think that’s the best standard to be running for office,” DiNapoli said early on.

DiNapoli touted his history of public service, as a local school board member for a decade and then 11 terms as a member of the State Assembly, where he served on the Ways and Means committee, he said. He defended being appointed to the position of comptroller by the Legislature in 2007, a move that was opposed by many newspaper editorial boards, Trichter had noted, arguing DiNapoli was unqualified for the job.

In his time as comptroller, DiNapoli said he has restored the integrity of the office, helped guide state finances through the Great Recession, and grown the pension fund to an all-time high. “That is an enviable record,” he said.

Trichter pitched himself as a candidate who would take a “fiscally pragmatic” approach to the comptroller’s office, banking on his credentials as a public finance expert with years of experience in the private sector as he critiqued DiNapoli’s management of state finances over the last decade-plus. He said DiNapoli had only created an average 6 percent growth over 11 years for the state pension fund, though his target was 7.5 percent, a gulf of $65 billion that he accused DiNapoli of extracting through taxation from municipalities. “The state comptroller has siphoned off local tax dollars ten times more than localities around the country have for their own public pension problems and underperformance,” he said.

Trichter said he would invest the pension fund in passive index funds such as the S&P 500 -- which mirror the rise and fall of the larger market -- and move away from investing in hedge funds and private equity, managers of which he said have received more than $6 billion in fees from DiNapoli’s office since 2007. “He’s paid $6 billion to hedge funds for underperformance,” Trichter alleged.

DiNapoli, in his defense, repeatedly accused Trichter of issuing misleading arguments and outright falsehoods, noting that the state pension fund grew by $100 billion under his tenure, that state pensions are funded up to 98 percent, with a diversified portfolio mitigating risk, and that the state weathered the storm of the recession. He also said New York’s outlook has been more conservative, with a new target of 7 percent growth for the pension system.

“To put all of our money in index funds would be totally irresponsible, to put all your eggs in one basket,” DiNapoli said, noting that hedge funds performed better when markets crashed during the recession, balancing out the poorer performance of public equity funds. “If we did learn anything from the global financial crisis, you have to be diversified.”

Dunlea, who co-founded the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), a good government group, and the Fiscal Policy Institute, a nonprofit think tank, said the pension fund would be $22 billion richer if the comptroller had divested it from fossil fuels ten years ago, even as he praised DiNapoli for divesting from the private prison industry and taking some steps in the direction of fossil fuel divestment.

“When the world is saying an industry has to end, that’s not a wise financial investment to continue somewhere between $6 to $11 billion,” Dunlea said of fossil fuel companies and the state pension fund.

DiNapoli insisted that simple divestment would not solve a problem as large and daunting as climate change and that the comptroller could more effectively push for environmental friendly corporate policies from within the room, as an activist shareholder in major fossil fuel companies.

He touted a $7 billion investment allocation in sustainability initiatives through the state pension fund and insisted that short of broad societal transition away from reliance on fossil fuels, the industry continues to provide a safe return on investment. “Climate’s a big issue and just selling stock in fossil fuel companies is not gonna solve it,” he said. When asked by the moderator if his argument was that fossil fuel companies continued to be a good investment, DiNapoli said “[W]e have to go through a societal change and for now, in the short run, we still are making money from the oil and gas stocks.”

“I don’t like the concept of being the sole trustee,” of the pension fund, said Gallaudet. He said he would urge the state Legislature to create a board to oversee the pension fund rather than have it in the hands of the comptroller alone. DiNapoli sought to demystify the comptroller’s role by noting he is not there making all the investment decisions by himself, far from it, he pointed to his bevvy of internal employees and “advisory committees.”

Audit Power

On the audit powers of the comptroller that allow the office to conduct oversight of state agencies and contracts and public authority spending, the candidates showed some disagreement.

“I think we need to be more aggressive about examining pay-to-play contracts,” said Dunlea, insisting that the comptroller needs to pay extra attention to individuals and entities that make large campaign contributions to elected officials and have business before the state. In particular, he pledged to closely examine local social services departments to ensure that needy people get the benefits they are entitled to receive.

Gallaudet simply said he would use the comptroller’s audit power to “reduce the scope of government,” though he did not elaborate how.

Trichter said the audit power is “one of the more powerful roles of the office,” as he critiqued DiNapoli for failing to use it appropriately. For instance, he alleged DiNapoli had repeatedly audited the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) but failed to unearth its many fiscal troubles even as the subway system has slid into disrepair and its capital funding needs ballooned to nearly $40 billion. “He’s the one Albany politician responsible for finding out what’s wrong with our infrastructure at the MTA before things start to break,” Trichter said, pointing to dozens of comptroller audits of the MTA that he said were outpaced by one New York Times reporter, though he also cited think tanks Citizens Budget Commission and The Manhattan Institute.

DiNapoli, however, insisted he has been a responsible and effective watchdog, including on the MTA. Dismissing Trichter’s criticisms as “crazy notions,” he said he had repeatedly raised the alarm about the MTA, including on its antiquated and failing signal system, and that his office has conducted robust audits of state agencies. “The strength of our audits is the credibility of the work that we do, and in many cases, we’ve effectuated change…We’ve saved taxpayers money through our audit work,” DiNapoli said.

State Budget Oversight

On state budget oversight responsibility, DiNapoli sought to portray the comptroller’s powers as limited, though he acknowledged he has a bully pulpit to advocate for more transparency and accountability. New York State’s budget process is notoriously opaque, and the annual spending document is invariably hashed out in the dead of night, with little public review, by the so-called “three men in a room” -- the governor, the Assembly speaker and Senate majority leader -- with a variety of gimmicks, hidden aspects, and unspecified, lump sum appropriations.

“Our role is one of lending a voice,” DiNapoli said. “And what we’ve tried to do with our budget reports, and what we’ll continue to do, is not only focus on the short term but on the long term.” He issued a note of caution about growing budget gaps in the years ahead, insufficient rainy day funds, and the heavy reliance on lump sums that hide the true purpose of spending. “Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the Legislature and the governor to make sure that these issues are addressed.”

Dunlea promised to more aggressively pursue budget oversight, pushing for reforms also backed by DiNapoli that give the comptroller more power over state contracting. He also said the comptroller should push harder on tax fairness and crack down on “out of control” debt incurred by public authorities.

“It is within the comptroller’s authority to refuse certifying the budget every year,” Trichter insisted, arguing that under the state constitution, the comptroller can leverage that certification power over the state budget to push for reforms. Though what Trichter is suggesting has never been tested, he believes it would hold up under the precedent set by the 1971 case of Posner v. Levitt in which the New York State Supreme Court’s appellate division ruled that the Comptroller “may have standing to test the validity of the budget, but he is not obliged to do so,” and could not be compelled.

DiNapoli has denied that interpretation. “[H]e’s making things up as he goes along,” he said of Trichter. “The comptroller has no authority to certify the budget. There is no statutory constitutional authority to do that. You can’t make up law.”

“If you’re gonna try to assert an authority that you don’t have, well all you’re gonna do is gum up the works and create more gridlock than you have already,” he added. “You’re gonna end up in court.”

Cross-Examination

The candidates were also given a chance to ask a question of one other candidate, which Trichter and Dunlea unsurprisingly used to question Dinapoli, who is seen as a prohibitive favorite to win reelection.

Trichter accused DiNapoli of participating in secretive payments to silence the women who were victims of sexual harassment by former Assembly Member Vito Lopez and asked if he would apologize. Dunlea pushed him on how he would avoid conflicts of interest in the future, pointing to a recent news report that showed the former Chief Investment Officer of the state pension fund, Vicki Fuller, joining the board of a company in which the state pension fund was invested.

In both cases, DiNapoli denied the accusation. He insisted that the comptroller’s office put in more accountability measures following the Lopez scandal, and that he had no say in negotiating the payments made to Lopez’s victims, nor were the submissions for those payments made to his office for approval clearly identified as related to sexual harassment. He said that his office certifies thousands of payment requests from the Legislature and indicated the settlements hadn’t appeared abnormal. “Women were victimized. They were entitled to some justice and entitled to compensation,” DiNapoli said. “That was the agreement. We made sure that they were paid. There was no secret payment...and in the aftermath of what happened with the Lopez situation, we did institute changes, more transparency, more accountability...and of course we’ve all evolved governmentally on this issue.”

And DiNapoli pushed back against the alleged conflict of interest, noting that the pension fund is invested broadly in hundreds of companies, that investments were made on the merit and that the former CIO is barred under state law from doing any business with the pension fund for two years. He said that the bulk of the company’s debt that the pension fund purchased three years ago was quite unlikely to have influenced where Fuller landed after retiring from the comptroller’s office this summer.

DiNapoli used his own question to give Gallaudet more time to say anything he wanted, and Gallaudet asked Trichter to explain how he could justify voters backing him given DiNapoli’s strong chances of winning, which gave Trichter another minute to reiterate his case.

Managing State Debt and Federal Tax Reforms

DiNapoli has repeatedly flagged that there is too much governmental debt in New York, for the state government as well as local governments and authorities. On managing such debt, there seemed to be at least some area of agreement among the comptroller candidates on the ends if not the means. Dunlea said again that he would rein in public authorities and make their workings more transparent. Gallaudet conceded, “I have no silver bullet, no easy answers on how to tackle this issue.”

Trichter, however, insisted, “I do have a silver bullet or a magic solution to all of this.” He said the state should end so-called “backdoor borrowing” or incurring debt without getting approval from voters, which is otherwise required by the state constitution and often happens through the public authorities.

“The comptroller has signed off on $32 billion in backdoor debt since he’s been in office in 2007,” Trichter said. “If he refused to sign off on backdoor debt, he could unilaterally end the practice once and for all and institute his own debt policy. This is something he absolutely has the authority to do.” He also noted that DiNapoli himself has supported a constitutional amendment to end backdoor debt.

Yet again, DiNapoli said Trichter was being misleading. “You can’t create authority or powers that you don’t have...It is not our authority, nor should it be our role, to just stop the debt that happens in the state,” he said, while also insisting that his office had reduced negotiated debt where it could do so.

There was little clarity on what the comptroller candidates would recommend or do about the federal tax overhaul passed by the Republican-led Congress and signed by President Trump at the end of 2017 -- reforms that Governor Cuomo and some in both major parties have decried as harmful to New Yorkers. Trichter said the office could not do anything about it and DiNapoli seemed to feel the same even as he praised Cuomo and the state Legislature for attempting to create a workaround for state taxpayers suffering from the reduction in the deductibility of state and local taxes (SALT), though those attempts may not pan out, he noted.

Lightning Round of Questions

In a brief lightning round, there was no unanimity among the candidates. All of them except Trichter supported extending the state’s soon-to-expire “millionaires tax” on income as well as a $15 minimum wage (Dunlea said it should be $20); Trichter was the only one opposed to the state passing a single-payer health care law, though DiNapoli said it should be federally funded.

Trichter had no answer on whether congestion pricing should be enacted to raise funds for mass transit while Dunlea and DiNapoli supported it (Gallaudet just said he wasn’t opposed). Dunlea and DiNapoli said they want the state’s fracking ban to continue, while Gallaudet and Trichter said fracking should be allowed.

All of the candidates favored holding state government hearings on sexual harassment in the public and private sectors, though Gallaudet said he wasn’t sure about the issue. He also had no opinion on scrapping the much-critiqued Joint Commission on Public Ethics, the state ethics entity often seen as too close to state power brokers, while the other three said they would like to see it replaced with a more independent body.

They all agreed on one lightning round question: closing the loophole in state campaign finance law that allows limited liability companies, which often have opaque ownership, to circumvent individual contribution limits, though Trichter added that it should apply to labor unions as well.

DiNapoli has committed to one other debate, being hosted by NY1 at the end of the month.

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Cuomo Challengers Level Critiques; Will Anything Stick?

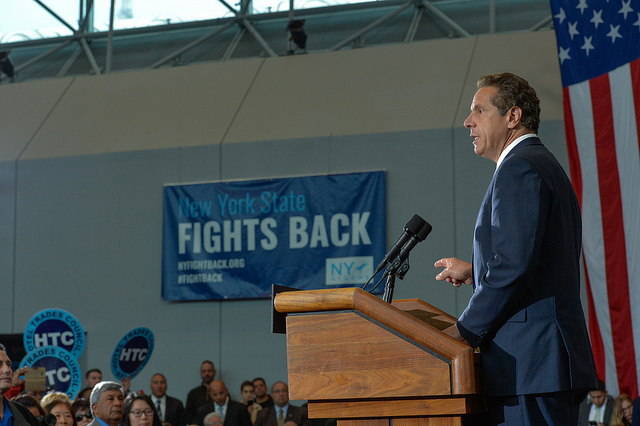

Gov. Cuomo (photo: Mike Groll/Govenor's Office)

With less than a month till voters go to the polls on November 6, it appears Governor Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, has little cause for worry as he seeks a third term. His favorability among voters may have dropped but public polling has shown him holding consistently wide leads over his opponents. His campaign war chest, though massively depleted by a bruising primary battle, still remains formidable at $9 million-plus, dwarfing his four general election competitors. And he is instantly recognizable to most voters, unlike his challengers.

Though Cuomo saw some of his weaknesses -- including a crumbling subway system and an epidemic of corruption in state government -- exposed and prodded in the primary by actor and activist Cynthia Nixon, a first-time candidate who managed to get more than half a million votes, he nonetheless came through it in relatively good shape, albeit with some egg on his face, defeating Nixon by 30 points with nearly a million votes of his own as primary turnout surged.

Despite several gaffes and scandals, questionable use of his government powers for apparent campaign purposes, and an egregious mailer that falsely smeared Nixon as anti-semitic, Cuomo emerged after primary day with an emboldened sense of his accomplishments, support, and chances at a third term. He also turned the corner in a campaign already geared largely toward opposing President Donald Trump, now with the opportunity to directly tie his main competitor to the president who remains unpopular in his home state.

With few signs that voters, at least Democratic ones, will punish him for a litany of troubles associated with his administration and his failure to have passed progressive legislation urgently demanded by an energized base, he is surging ahead in a race that is his to lose. While Cuomo has said little directly to make amends with those 500,000-plus Democrats who voted for Nixon, one major step he has taken is to begin following through on a pledge to help flip the New York State Senate to Democratic control, and help flip New York seats in the House of Representatives as part of a national effort to give the chamber a Democratic majority.

As Cuomo woos the state’s 6.2 million Democratic voters and its 2.6 million independents, among others -- including some of the 2.8 million Republicans who may like aspects of his moderate record -- the governor’s opponents have been leveling attacks against the incumbent with the hopes of taking him down a notch while building their own stature. Polling indicates those efforts have not yet borne fruit, and as the election rapidly approaches, a governor with significant achievements and vulnerabilities appears to be deflecting, dodging, and defusing criticisms of his record on corruption, jobs, taxes, the MTA, and more.

In the latest Siena College poll, the first of the general election, released October 1, Cuomo held a 22-point lead among likely voters over his main rival, Republican nominee Marc Molinaro, the Dutchess county executive. Cuomo received 50 percent of the vote to Molinaro’s 28 percent. Ten percent said they would vote for Nixon if she stayed on the Working Families Party line, which has since gone to Cuomo, paving the way for him to capture a higher percentage, while 4 percent said they would vote for other “third party” candidates, who include Green Party nominee Howie Hawkins, Libertarian nominee Larry Sharpe, and independent Stephanie Miner; and 8 percent were undecided.

“Electorally, barring something unexpected, a month out now, it’s hard to imagine that he’s going to do anything except walk away with this thing,” said Dr. Jeanne Zaino, professor of political science at Iona College, in a phone interview. “I’m not sure that that speaks as much to the governor as it does to the fact that Republicans in the state are in a very, very difficult position.”

As Molinaro runs uphill against an anti-Trump wind, Miner, the former Democratic mayor of Syracuse now with the new Serve America Movement, has struggled to gain traction with her message of experience and bipartisanship. Hawkins, who received 5 percent of the vote in the 2014 gubernatorial race, says he hopes to beat that this year, but is severely underfunded, and Sharpe, who has kept an especially active campaign schedule, does not appear to have broken through.

Some of the major criticisms levelled by the challengers are similar to Nixon’s own volleys against Cuomo, that he has allowed corruption to fester in government, catered to wealthy donors at the expense of everyday New Yorkers, largely mismanaged a multi-billion-dollar economic development program, and let New York City’s subway system slide into chaos.

There are of course more specific critiques. Molinaro and Miner, for instance, have both stressed that taxes are far too high and living in the state has become increasingly unaffordable, blaming Cuomo for the resulting exodus of New York residents, especially from distressed upstate areas. Hawkins has condemned Cuomo’s environmental policies for not going far enough, laments that the governor does not support state-funded single-payer health care (Cuomo believes the federal government should pass it and pay for it) and argues that the state has yet to fund the foundation aid formula for fair student funding across the state as required by the Campaign for Fiscal Equity court decision. Sharpe wants to repeal the SAFE Act, Cuomo’s signature gun control measure passed in the wake of the Sandy Hook massacre, and significantly reduce the size and scope of state government in other ways, returning more power to localities.

Besides the seemingly insurmountable advantages of incumbency, Cuomo has largely chosen to ignore his opponents and focus on Trump, in a year where Democrats are seeing the signs of a “blue wave” across the country. He has sought to paint Molinaro and nearly every New York Republican as a “Trump mini-me” who supports what he says are harmful policies of a Republican-led federal government and the retrogressive outlook of a platform based on the president’s pledge to “Make America Great Again,” which, to Cuomo and many others, includes racial and ethnic prejudice.

“Molinaro is vastly, in almost every way, he is on the losing end of this,” said Zaino. “From name recognition, to funding, to party registration, I mean up and down this is a very tough year for Republicans.”

Besides taxes, Molinaro’s campaign is largely built on highlighting the corruption scandals that have marred Cuomo’s two terms in office, and on painting Cuomo as an incompetent leader who relies on intimidation tactics.

“Andrew Cuomo has no credibility,” said Katy Delgado, a Molinaro campaign spokesperson, in a statement. “The people of New York are suffering from high taxation and corruption has stained the Governor’s office. It’s time for New Yorkers to have the leadership we deserve. A Governor who will cut taxes by 30% and show this corrupt administration the door on January 1, 2019.”

In fact, in the Siena Poll, likely voters said that by a 41-36 percent margin, Molinaro would do a better job of tackling corruption (a majority said Cuomo is better on infrastructure, public education and job creation). Cuomo came into office in 2011 promising to clean up state government, and has failed to do so, with recent federal convictions resulting in members of his inner circle headed to prison, along with a long list of state legislators who have been removed from office for abusing the public trust. But those results appear to have done little to sour voters on Cuomo.

Zaino said the trifecta of corruption, the MTA, and taxes are areas where Cuomo could see some disaffection among voters. “He is very vulnerable on corruption,” she said. “He’s made the case obviously that it’s not him, but it has been people very, very close to him. And he hasn’t done enough to put a stop to it, as he promised eight years ago.”

Government corruption has not proved to be a major voter motivator, however.

The issue of the MTA also “strikes very close to home for some voters,” Zaino said. “The MTA is something that people deal with on a daily basis, and that is his, and he owns it.”

On taxes, she said Cuomo is between a rock and a hard place -- a progressive left movement that wants to see higher taxes on the wealthy and Cuomo’s own predilection for fiscal moderation. “I think he’s going to be caught in between this progressive left, and obviously Republicans, but also more importantly, the moderate Democrats, and I think it’s really going to highlight some of the upstate-downstate tensions as well,” she said.

Dr. Christina Greer, political science professor at Fordham University, also pointed to the governor’s strengths in the general, chiefly the campaign cash at his disposal. “Money in many ways can elevate his narrative and drown out his opponents’ narrative,” she said in a phone interview. “I think he’ll use it strategically. I think Molinaro has an uphill battle because he doesn’t have name recognition and he doesn’t seem to be inspiring voters as of yet.”

New York City is the most expensive media market in the country and Cuomo’s millions in campaign cash can buy him ample air time, in the city and beyond. “Cuomo certainly has vulnerabilities,” said Siena College pollster Steven Greenberg. “He can have a vulnerability but if the voters don’t know about it, it’s sort of the tree in the forest.” On corruption, for instance, he said Molinaro would have to work hard to make it a “salient” campaign issue among undecided voters who aren’t already pledged to either of the two major party candidates.

“[Molinaro] has to worry about the folks in the middle,” Greenberg said. “Independent voters, those soft Democrats, those moderate Democrats, those moderate Republicans, the folks in the middle, the folks who decide elections. But that costs money.” Molinaro’s latest campaign finance disclosure from this week showed he had only about $210,000 in cash on hand.

Greenberg also noted that a Republican has not prevailed in any statewide race since George Pataki won a third term as governor in 2002.

“For a Republican to win statewide is a very difficult proposition…How do they do it? They win upstate. They either win or hold their own in the downstate suburbs and they find a way to cut the deficit in New York City...Marc Molinaro can put out statements every day, he can do events every day, but the vast majority of voters don’t see those statements or know about those events. You gotta get on TV, you gotta be on radio, you gotta do mailings, you gotta do phone calls, you gotta have the volunteers to go door-to-door and talk to voters. All of that is expensive.”

Greer, however, doesn’t believe Molinaro has made an effective argument against Cuomo. “I don’t know if Molinaro has the message to sway voters. Cuomo has an advantage because all he has to say is ‘Molinaro is a Republican’ and that will turn off many Democrats,” she said. “That’s a strong card to have in this moment.”

But, she noted, there is likely to be some voter fatigue with Cuomo having been in office for nearly eight years. “He’s asking people for a third term and I think some folks just don’t feel like he deserves it,” Greer said. “Based on temperament, based on lack of productivity in particular areas that they’re interested in.”

The challengers themselves are confident of breaking through to voters, noting what they see as Cuomo’s weaknesses, his lack of a coherent vision for a third term, and the fact that more than 500,000 voters cast a ballot for Nixon in the primary.

“Governor Cuomo’s entire campaign is based on his fear of Donald Trump alone,” said Sharpe, the Libertarian candidate, in a statement. “There is no plan to actually help any New Yorker in any way, shape or form. It is only a fear-based platform.”

Sharpe said Cuomo has focused on “the crown jewel” of $22,000 in per-pupil education funding, which the governor repeatedly cites as the highest in the nation. But Sharpe says the state ranks below 30th in education outcomes. “This crown jewel is actually a cubic zirconia. The current educational system is an expensive and bloated embarrassment for which he should be ashamed. Everything else of value he has abandoned, including economic development, the family courts, the MTA and infrastructure overall. His 8 years can be summed up in one statement, ‘One million New Yorkers have voted with their feet by leaving the state since his majesty took the throne.’”

Hawkins of the Green Party is banking on progressives being dissatisfied with the governor, and thinks he is the logical choice for Nixon voters in the general. “He talks progressive but he governs to the right,” Hawkins said of Cuomo in a brief phone interview. He pointed out, for example, that the governor’s much-vaunted $15 minimum wage isn’t in effect upstate, where the minimum wage is set to increase to $12.50 by the end of 2020. He criticized Cuomo for hesitating on extending the state’s millionaires tax, his handling of issues at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), and lead poisoning issues in upstate communities in Syracuse, Buffalo, and Ithaca.

“I think it resonates but the question is, do we have the reach to reach all the progressives who I think on these issues are the majority of people in New York State,” Hawkins said.

He recognized Cuomo’s many advantages. “The only way we can overcome it is if the media narrative changes,” he said, noting for instance that though the Green Party received more than twice the votes the Working Families Party did in 2014 (with Cuomo on its line), the WFP’s political moves tend to get more attention. “That would make a big difference...It’s not just what Cuomo’s got, it’s the way he’s being treated by the media, which is frustrating for us.”

One way Cuomo's challengers could earn a boost and the governor could potentially fall in favorability is through a debate, but Cuomo has yet to agree to one, and while he may, the odds of such an event having a drastic impact on the race are small. Cuomo survived a contentious, high-stakes one-on-one debate with Nixon in the primary; if he agrees to a general election debate, he's likely to insist all five candidates are present, diluting his exposure.

In a phone interview, Miner reiterated her three-part criticism. “The state government is mired in corruption, money is being wasted, and problems are not being solved,” she said. Miner believes that though Cuomo had a decisive primary victory, the general electorate is likely to more accurately reflect and vote on statewide issues. “I think you’re gonna have a much broader and more representative population across the state that’s gonna vote,” she said. She believes Cuomo will continue to spend massively in the general because “he has to try to distract people from the fundamental problems that are happening in New York state under his administration and his tenure.”

It’s unclear what the general electorate will look like, though trends including Democratic enthusiasm appear to be to Cuomo’s advantage. Nixon’s move from the WFP line to make way for Cuomo and eliminate any chance of her being a spoiler also works toward his securing a third term. But, a Cuomo win is not necessarily a complete given.

“Anything can happen in the real world,” said Greenberg of Siena. “So is it a foregone conclusion? No. Is he the prohibitive favorite? Would you go to Vegas and place a bet on it? Absolutely.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

A Lifelong Democrat and Famed Civil Rights Attorney, Michael Sussman Runs for Attorney General as a Green

photo via Sussman campaign on Twitter

A 19-year-old from Flatbush, Brooklyn sat in the Iron Forge, a middle-eastern restaurant on Q Street in Washington, D.C., and looked around. He had started his internship with the Democratic National Committee, and was given the opportunity to choose from a group of candidates whose campaign he wanted to work on. He saw the men around him, who he would work with in the coming months, the fall of 1973: Georgians Hamilton Jordan, Jodi Powell, Bert Lance, and Griffin Bell, along with the governor, Jimmy Carter.

The young Brooklynite took that fall semester off from college as he transferred from the University of Chicago to Amherst College, immersing himself in politics, and went on to work on Carter’s campaign for president, meeting Ralph Nader, a well-known political activist and attorney credited with pushing consumer protection legislation such as the Clean Water Act, Freedom of Information Act, Whistleblower Protection Act, and more. He learned from Nader, and worked with him and Mark Green, later the New York City Public Advocate, on environmental issues, and went on to do his own public-interest work as a civil rights lawyer, including in the Department of Justice and for the NAACP. His most famous work came in Yonkers, New York, where he won a landmark case aimed at tearing down the city’s racial segregation, among other cases, and where he organized his fellow Democrats, holding rallies, and speaking at many public events on a variety of causes over decades.

Now 64 years old, Michael Sussman is running for Attorney General of New York as the Green Party candidate, his first run for statewide elected office after decades of political and legal work advancing progressive causes. He’s abandoned the Democrats for the Greens, he says, because “leading Democrats in the state have failed to advocate strongly enough for the interests that I care about, and I think that in some cases they’ve failed to do that because of personal interests and corruption.”

He’s running for attorney general because “from corruption to public health to the environment...these areas are all of huge and critical importance and I think you need someone as attorney general who has life experience as a litigator.”

He’s promising if elected to investigate Governor Andrew Cuomo, who is favored to win a third term this fall, and he’s pulling few punches when it comes to the frontrunner in his race, Democratic nominee Letitia James, currently the New York City Public Advocate, who has Cuomo’s full backing.

“I was a Democrat for 45 years,” Sussman said at a recent candidates event in Yonkers, addressing the crowd just after James spoke. “I ran for county executive of my county, I’ve done some of the most significant civil rights and environmental cases of my generation, but I refused in 2017 to run as a Democrat in New York State for Attorney General, for one good reason: the duopoly of corrupt practices.”

“We cannot have someone running on the slate with Mr. Cuomo expected to vigorously prosecute Mr. Cuomo and political corruption in our state -- it’s an inherent conflict,” Sussman said, “and until and unless we recognize it frontally and say we need an independent attorney general, someone like me who has 40 years of experience litigating, in every court -- Supreme Court of the United States, 400 arguments in the Court of Appeals in New York, a thousand cases in federal court...I don’t want to depend on the Trump Justice Department to clean up political corruption in New York. I want an attorney general in New York who is independent enough to clean up corruption, it’s very simple.”

If he can somehow get enough New Yorkers to hear his message and consider voting Green, Sussman believes he would be the clear choice for attorney general among voters who are overwhelmingly Democratic. He’s traveling the state, walking local communities from Brooklyn to Buffalo, he says, posting short videos to his Twitter feed, and proposing things like strengthening the public integrity unit of the attorney general’s office and imposing “a sweeping public finance law to disconnect big money from state politics.”

Lou Young, Sussman's communications director, tweeted, “If he could meet every voter in person he would win in a landslide. Michael Sussman just needs to he heard to be believed. It's that simple.”

He won’t meet every voter and it may not be that simple even if he did, of course, given the strength of James’ candidacy, which includes the powerful backing of Cuomo and the state party he controls, not to mention challenges raising money and name recognition.

While the odds of him pulling off a victory that would shock New York, and beyond, are quite long, Sussman is the type of “third party” candidate who may garner significant attention in a political atmosphere where voters on the left are frustrated with what many perceive as a corrupt and disconnected gubernatorial administration and state Legislature. But how many of the hundreds of thousands of voters who backed Cynthia Nixon for governor or Zephyr Teachout for attorney general in their respective Democratic primaries are willing to consider Sussman is an open question, especially given James’ progressive bona fides (she would also be the first woman of color to win a statewide position).

But with the question of independence from Cuomo still hanging over the attorney general race, which also includes Republican nominee Keith Wofford, among others, and given his decades of relevant experience, Sussman believes more voters should take a look at his campaign.

Roots

Sussman, born in 1954 the son of an accountant father and music teacher mother, is unsure exactly where his interest in civil rights first began. Perhaps from his father, who had done work with African-Americans in the discriminatory south but emphasized to his son that the north was no different, or from his grandmother, a radical socialist. But Sussman points to something simpler.

“I always had a feeling in the playground for the underdog,” Sussman said in an hour-long interview. “When we chose teams to play ball and I was 6, 7, 8 years old, I was a fairly good athlete then and would always take the kids on my team that the good athletes didn’t want on their team. It’s something that I can remember back a long way, feeling an affinity for people who are viewed as either nonconforming or not functional at the same level — whatever that level was — of others, and otherwise being excluded from the game so to speak. So I guess my life’s work has been about that subject in a general sense and consistent for a very long time.”

“For whatever reason and however it happened,” Sussman says, his upbringing “imprinted on me a sense of obligation that even though we were not a wealthy family, we were a middle-income family, that our job was essentially to give back.”

Sussman says he decided at age 12 he would do this by becoming a civil rights lawyer. Although he would go on to represent people of color in countless cases, Sussman says he grew up in a monoracial Flatbush. The only black person he knew was his mother’s maid, he said, adding that having a maid was “somewhat usual for even middle-income people in those days.”

“I remember trying to understand the experience of, Esse was her name, as even though she lived in New York City, in the same borough we were in, it seemed like miles away, centuries away,” Sussman said.

Later, while attending the University of Chicago as an undergraduate, Sussman had his internship with the DNC, meeting Jimmy Carter. Yet Carter’s early presidential campaign was not the most historic event he was being exposed to — his uncle, Barry Sussman, was then an editor at the Washington Post, Michael Sussman recounts, and it was in Barry’s home that the now famous Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein began their investigation.

“So I was able to see the origins of the Watergate case as it was developed in their basement in Barry’s house in Potomac, Maryland, and then during the days I worked with Jimmy Carter,” Sussman said about his 1973 experience.

Sussman says he’s sought to surround himself with people doing great things.

“I’ve always told my children, I have seven children, ‘Try to find yourself amongst the people who are doing what you think is important,’” Sussman said. “I think that you have to see what your capabilities are, you have to see who is doing work that you emulate and that you admire, and I think you have to try and put yourself in a position to learn from greatness, really.”

While Sussman is not a household name himself, he became a prominent civil rights lawyer with an acclaimed show on HBO, “Show Me a Hero,” about his most famous case.

Resume

Sussman graduated in 1978 with honors from Harvard Law School, where he was in the same class as now-CEO of Goldman Sachs, Lloyd Blankfein, who Sussman says “was not a stellar student.” After graduating, Sussman took his most well-known case, the aforementioned, representing a local chapter of the NAACP in Yonkers that sued the city for its segregated school districts. After 26 years of legal proceedings that went all the way to the Supreme Court, the 2007 result was $300 million in funding to desegregate schools and build affordable housing.

Out of law school, Sussman had been working at the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division in October of 1978, during Carter’s presidency. He worked on efforts to stop school segregation and housing discrimination. However, Sussman says this changed in 1981 when Ronald Reagan became president. According to Sussman, William French Smith, Reagan’s attorney general, said that the Civil Rights Division needed to focus on elevating the rights of white people. Sussman says he “made a fuss internally,” speaking to a former debate partner of his from University of Chicago and the man he was working under, Deputy Attorney General Edward Schmults. After getting no response, Sussman left the Justice Department, and was offered a job with the NAACP.

“I met the major forces in American Civil Rights Law at that time: Joseph Rowl, William Taylor, Thomas Atkins, Nathaniel Jones, lawyers from generations older than mine who were doing the major work as I thought,” Sussman said, “and I became friends with them and they viewed me as someone that could carry on the work. So, I was blessed to be offered a job as assistant general counsel at the NAACP national office in New York City.”

It was then that Sussman began work on the case, which had been filed by a local chapter of the NAACP in 1980. The case accused the city of Yonkers — including city officials, lawyers and judges — of being discriminatory and engaging in housing segregation, which caused school segregation. To diminish said segregation, the city and school board would have to work together to reorganize the school system and create housing opportunities for low-income people that were not in “ghettoized areas,” as Sussman put it.

Believing the Reagan administration’s stance on civil rights made it unreliable in defense, the national office of the NAACP saw an opportunity to become involved and secure a victory. Still, it was 2007 before a ruling in the case, with Judge Leonard B. Sand ruling in favor of the NAACP and ordering Yonkers to build 200 public housing units and allow 600 houses to go to low-income families in the majority middle-class and white east side of town.

Sussman’s civil rights career unfolded alongside that case, with some cases taken on behalf of friends but most dedicated to advancing certain causes, he says. He has represented a Pace University student who was shot by police in 2010 — although the Justice Department decided not to charges against the officer involved — and won $6 million for the family, and won a $45 million settlement against the state for black and Hispanic workers in a discrimination case, for example.

Sussman now lives in Orange County, where his law firm, Sussman and Associates, is based in the town of Goshen. While he’s mainly worked in Washington, Yonkers, and Orange County, Sussman has also opened “empowerment centers” designed to help underprivileged people in Liberty, Monticello, and Port Jervis.

Sussman has also worked defending students suspended by their schools, including Elzie Coleman, then a potential Olympic sprinter who was suspended for getting in a fight. Sussman argued that suspending Coleman violated his due process and would cause “immediate and irreparable harm” as it would impact Coleman’s ability to qualify for scholarships necessary for him to go to college. Sussman used this same argument in a variety of cases against school districts. He also represented Putnam County District Attorney Adam Levy in a case of defamation, after the sheriff of the county accused him of harboring an undocumented immigrant, among other things — Sussman won the case, reaching a $150,000 settlement.

In a case of sexual harassment, Sussman represented an Orange County Health Department worker who accused her boss of making sexual advances, and firing her after she refused them. Sussman says his work was mainly centered around certain causes, while he occasionally took work due to relationships with clients.

“There are situations where people will come to and out of personal loyalty or out of the feeling that there is some important issue that is being raised in their case, I will defend them, if you will,” Sussman said. “Most of the work I’ve done is not based on that. Most of the work I’ve done is based on what I might call cause-driven lawyering. That is, I’m known to do cases of employment discrimination, sexual harassment, education law.”

In some cases Sussman found him defending those accused of sexual harassment, rather than the other way around. In 2002, when a coworker accused forensic scientist for the New York State Police John Graziano of sexual harassment, her complaint did not lead to any punishment, as despite human resources finding probable cause, it did not go to trial. After this, women working with Graziano started treating him poorly, and so he filed a lawsuit alleging they harassed him due to his gender, suing under Title IX. Sussman defended him in this case, which was dismissed.

One of the students Sussman represented was suspended for allegedly having sex with two girls on school property, but separately accused of forcing another student to touch him sexually. Sussman focused on the cases of sexual activity, and claimed that the school punishing him much more severely than the girls involved was a Title IX violation. He won the case.

“It posed an issue of gender stereotyping that I think is interesting and important,” Sussman said. “[The student] was engaged in what the school district defined as consensual sexual activity with two girls in school, separately, and the two girls were slapped on the wrist and he was suspended for a school year basically and I thought that was absurd.”

According to a press release announcing his 2018 run for attorney general, the Green Party highlighted that from 2006 to 2010, Sussman represented “a class of 4,700 African American and Hispanic state workers [against the Attorney General’s office] in a lawsuit challenging the promotional test used by the State of New York for civil service promotions” and that the “cae ended in a settlement of $45,000,000 for the class.”

One apparent blemish on Sussman’s record came in 2002. In 2014, the New York Post reported that in 2002 Sussman had had his law license suspended for a year for “commingling personal and client funds.”

Running for Attorney General

It is in the areas he’s focused his legal career that Sussman believes the state should be enforcing laws more strictly. He argues his experience makes him uniquely suited to do so if elected as attorney general, and should cause voters to take notice of his candidacy to become the state’s top legal officer, charged with upholding laws, defending the state in legal action, and other responsibilities.

“I feel that there needs to be vigorous enforcement of our state’s laws in those regards and I’m aware that laws are not self-enforcing,” Sussman said. “I’m also aware that there are not many civil-rights lawyers in our region that have expertise like I have in the courts.”

“It’s shameful that both in regards to civil rights laws and environmental laws and laws protecting health and safety in our state, the AG office has made, from my perspective, minimal contributions over the last 30 or 40 years, despite so-called progressive people running the office,” he continued. “Either they don’t understand the laws or they’re not really interested in enforcing them to the extent necessary in our state.”

Sussman, who had previously been on his town board as a Democrat, and ran for county executive of Orange County as one, says his shift to the Green Party in November came due to frustration over issues of corruption and failure to act by Democrats in New York.

“First of all, I feel that Mr. Cuomo is corrupt, I feel that Mr. Schumer is in the pocket of Wall Street,” Sussman said of Gov. Andrew Cuomo and U.S. Senator from New York Charles Schumer, the minority leader. “I feel that leading Democrats in the state have failed to advocate strongly enough for the interests that I care about, and I think that in some cases they’ve failed to do that because of personal interests and corruption. So I don’t see the Democratic Party right now as being the answer.”

Sussman gave an example of a Competitive Power Ventures gas-fired power plant being approved in his county despite residents being outspoken concerning the potential environmental and human health risks from large emissions of carbon dioxide, carcinogens, neurotoxins, and other dangerous chemicals. In this case, Sussman says neither Democrats nor Republicans would talk to protestors when trying to prevent the plant from getting approved. Yet, now that it has started operating, both Democrats and Republicans are against the plant. Both Democrats and Republicans, he believes, are seen by many as representing a politics-first mentality.

“Part of that increasing alienation is that people think both parties represent the same thing, and I think that’s true,” Sussman said. “Particularly for the attorney general race, I see a perpetuation of the same patterns of clubishness and I don’t think that’s going to solve anything.”

Sussman has been critical of James, the Democratic nominee, as seeking the attorney general position only to increase her chances of becoming governor in the future, of which there is little evidence, in part given James’ own background as a public defender and assistant attorney general. Recently, he has said that Republican nominee Keith Wofford also sees the position as a way to reach higher office, an assertion there’s also little support for as Wofford, a corporate attorney, runs for office for the first time.

“I genuinely believe that the Democratic Party candidate wants to be governor, which she has every right, but I don’t see this position as a stepping stone,” Sussman said. “With that sort of ambition, what ends up happening, is that people don’t do what they need to do in this office because of looking over their shoulder.”

At the Yonkers candidates’ event, Sussman both praised James’ work as public advocate and said that her use of the office as a litigator has been wanting, given that she has been kicked off of a number of suits for lack of standing. He said the two agree on almost every social issue, from taking on the NRA to protecting immigrants, but said that the deciding factors for voters must be his resume as an attorney and the contrast between his and James’ relationships with Governor Cuomo.

“I am ready from day one to litigate -- whether it’s Donald Trump or whether it’s Andrew Cuomo,” Sussman said. “And guess what, it’s going to be Andrew Cuomo.”

Cuomo’s shuttering of the Moreland Commission to Investigate Public Corruption was “insulting to every citizen in New York State,” Sussman said, speaking just after James. “I didn’t hear my opponent say one thing about him, nor would I expect to, she’s running on the same ticket. You can proclaim independence, but you can’t be independent if that’s your running mate, it’s simply impossible.”

On Wofford, Sussman said in the interview, “The Republican candidate is not someone who has experience with public law, he’s chosen other career paths, and I don’t think that you start in public law as attorney general of New York.”

“This is it for me, and if I get the position, against all odds, then I would use the office and the lawyers in that office, 672 of them, to the fullest extent I could do enforce the laws I see in New York that deal with discrimination and environmental degradation, health threats,” Sussman said, pointing to the powers of the attorney general to uphold certain laws in New York, along with the office’s responsibilities to defend state government. But on the latter, Sussman says, “I would do much less knee-jerk defense of state agencies, which engage, unfortunately, in ongoing patterns of segregated behavior, discriminatory behavior.”

Sussman has litigated against the state on multiple occasions, and believes that a 45-day review period should be put in place for every case filed against the state, allowing the attorney general’s office to decide if the state had committed whatever alleged infraction the suit claims. Sussman says if he were to find that the behavior is as it’s alleged and if it is lawless, he would not defend it — instead, he would “settle the case, resolve the issue, take action against the individuals and agencies responsible and clean up the state.”

“I would not just knee-jerk defend them in state or federal court. I would force those agencies to comply with the law,” Sussman said. “Again, no attorney general has ever said that or done that. Certainly my opponents in this race are not saying that or doing that. Tish James was with the state attorney general’s office and was involved in the defense of many discrimination cases, which is quite the contrary to my feelings and philosophy.”

Sussman continually asserted his advantage in experience over his competition, which also includes Libertarian Christopher Garvey and Nancy Sliwa of the Reform Party, and said that if elected he would begin to clean the state of the stains of corruption by pushing public campaign financing and prosecuting those who use their positions for their own gain.

“I feel that they don’t have the depth of my experience in public law, they don’t have the depth of my experience as an advocate,’ Sussman concluded about his opponents, “they don’t have the depth of my life experience, that’s just how I feel about it.”

***

by Victor Porcelli, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette

Ben Max contributed to this story.

Note: this article has been updated to clarify Lou Young's relationship to Sussman and Sussman's graduation status from Harvard Law School, which had been misrepresented to do a Gotham Gazette error.

Max & Murphy Podcast: Jonathan Trichter, Republican nominee for Comptroller

Ben Max, left, of Gotham Gazette, and Jarrett Murphy, right, of City Limits

October 03, 2018 - Jonathan Trichter, Republican nominee for Comptroller

Jonathan Trichter, the Republican candidate for state comptroller, joined the show to discuss his candidacy, including his critiques of incumbent Comptroller Tom DiNapoli and his plans for doing things differently if elected.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think -- we're on Twitter @TweetBenMax and @JarrettMurphy. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Max & Murphy Podcast: Comptroller Tom DiNapoli

Ben Max, left, of Gotham Gazette, and Jarrett Murphy, right, of City Limits

October 03, 2018 - Max & Murphy Podcast: Comptroller Tom DiNapoli

Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, a Democrat who has held the office for roughly ten years, joined the show to discuss his case for reelection.

Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, a Democrat who has held the office for roughly ten years, joined the show to discuss his case for reelection.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think -- we're on Twitter @TweetBenMax and @JarrettMurphy. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Klein, Filing Late Post-Primary, Shows Over $3 Million in Senate Campaign Spending

Sen. Jeff Klein meets voters (Photo: jeffkleinny.com)

Already spending at what is likely a record pace, with two weeks until the September 13 primary, New York State Senator Jeff Klein kept spending his campaign cash at a rapid clip to try to beat back a Democratic primary challenge from Alessandra Biaggi, a lawyer and first-time candidate, Klein’s late post-primary campaign finance filing shows. In sum, Klein spent nearly ten times more than Biaggi, but was still unsuccessful as Biaggi claimed the nomination, likely unseating one of the state’s major powerbrokers of the past decade, in the district that covers parts of the Bronx and Westchester.

Klein spent nearly $700,000 in September, out of more than $3 million -- an astronomical sum for a state legislative race -- that he depleted in trying to retain his seat in this two-year election cycle. He also raised another $246,000 in those final weeks of the primary -- he has brought in $1.8 million since January 2017 -- including $103,000 from the Senate Independence Campaign Committee, which he and partners originally set up jointly between the Independence Party and the erstwhile Independent Democratic Conference, a breakaway group of eight senators led by Klein that formed a power-sharing agreement with Republicans in the Senate. The SICC was ruled by a state supreme court judge to be illegal, though it apparently moved into compliance thereafter, and the state BOE had ordered that IDC members refund its contributions, but they refused. In total, the SICC directed $403,000 to Klein’s reelection coffers.

The SICC also moved hundreds of thousands of dollars, largely from major donors in real estate and education reform, to other members of the IDC, with Klein and five other former IDC members losing their primaries.

In the days leading up to September 13, Klein received $90,500 in donations from limited liability companies and from political action committees, including some associated with law enforcement unions and the nursing and beverage industries. Klein has benefited greatly from the largesse of corporations, PACs and LLCs, the last of which are not required to name their owners and can therefore circumvent contribution limits. In total, those types of contributors gave him about $1.16 million for his reelection.

There were a few notable individual donations in the most recent filing as well. On primary day itself, Carl Icahn, the billionaire investor with close ties to President Donald Trump, gave Klein $11,000; two days before that, hedge fund billionaire Paul Tudor Jones gave him $15,000; and in the week before, Larry Robbins, also a billionaire and of the KIPP charter school network, donated $10,000.

Of the latest spending spree, about $390,000 went to the Hamilton Campaign Network, a Democratic campaign consulting firm, which organized campaign mailers, phone and text banking efforts, and produced videos for Klein’s campaign.

After all his spending, Klein still had $510,000 sitting in his campaign account as of this filing, which was sent to the Board of Elections a week late. He could retain that cash or potentially transfer it to another campaign account, should he decide to run in any upcoming elections, or he can donate to other candidates running in the general. He may decide to use it for his own continued campaign, given that he has the Independence Party ballot line to run on in November after losing the Democratic nomination, and Klein has not formally conceded his race or endorsed Biaggi.

In the Democratic primary, Klein received 14,754 votes, about 44.5 percent, losing to Biaggi’s 17,618 votes, or 53.1 percent. All told, Klein spent roughly $207 for each vote while Biaggi only disbursed $18.90 per vote.

Independent expenditure groups also showed their support for Klein. Those include Laborers Building a Better New York, a group associated with the Construction and General Building Laborers Local 79 union, which spent $109,360 to favor several candidates, including Klein. New Yorkers for Quality Healthcare, affiliated with the Greater New York Hospital Association, spent a whopping $447,450 on digital ads, direct mailers, web design, and tv production to support Klein and State Senator David Valesky, another former IDC member who lost to his own primary challenger, Rachel May. The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association’s independent expenditure committee also spent $65,338 on direct mailers boosting Klein.

In total, Biaggi spent $332,000 on her campaign and raised about $534,000. While Klein was attempting a well-funded last ditch effort to sway voters, Biaggi only dropped about $160,000 in that final three week period, raising only $62,500 in the same time. She has another $133,000 as she heads into the general election, where she would be unopposed unless Klein continues to run.

A spokesperson for Klein’s campaign did not return a request for comment for this article. He has not appeared in public since primary day, and did not address supporters on primary night.

Biaggi also received outside help in the primary. The Empire State 32BJ SEIU PAC spent $97,285 to support her election, through mailers, canvassing efforts and social media ads. They also spent $11,540 on a mailer opposing Klein. The union, 32BJ, dedicated significant resources, including financial and human, to Biaggi’s successful bid.

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Cuomo Begins Push to Flip State Senate and House of Representatives

Cuomo & Long Island candidates (photo: @andrewcuomo)

Having resoundingly won the Democratic Party nomination for a third term last month, Governor Andrew Cuomo is now directing the enormous campaign and party machinery that propelled his victory to focus its efforts on the New York State Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives. In a break from past cycles when he has been criticized for doing too little for his party and its candidates, Cuomo has pledged to leverage the significant resources, financial and human, at his fingertips to help Democrats flip control of the two legislative chambers, one each at the state and federal levels, to better counter what he says are harmful policies of the Trump administration and Republican-led Congress.

On Monday, Cuomo stood alongside several state Senate candidates at LIU Post on Long Island, unveiling a nine-point Long Island-focused pledge to regain Democratic control of the legislative chamber -- Democrats need to pick up a net of one seat in the Senate, while in the Assembly they enjoy an overwhelming majority. Alongside a slate of Democratic Senate candidates, Cuomo signed the pledge, which includes measures he’s already put into place and others he has said he supports but hasn’t been able to get through the Republican-led Senate.

Cuomo and the battleground candidates promised to continue the state’s 2 percent property tax cap, which he says will protect Long Island residents from the federal government’s reduction of state and local tax (SALT) deductibility; he called for more funding for the MTA from New York City; he touted his $150 billion infrastructure plan, which includes modernizing the Long Island Rail Road; pledged to codify the protections of Roe v. Wade into state law; backed ethics and voting reforms; promised to continue investing in combating the MS-13 gang; and pushed his proposal for a red flag gun protection bill. He also spoke of providing more funding to public schools and protecting access to clean water.

“We need the New York State Senate, because the only security we’re going to have are the laws of the State of New York as they are tearing down our rights and values in Washington,” Cuomo said.

On Tuesday, the governor made a brief stop at the Stars & Stripes Democratic Club in southern Brooklyn to publicly endorse Andrew Gounardes, the Democrat challenging State Senator Marty Golden in one of the few New York City districts represented by a Republican. Cuomo repeated many of the same talking points from his Monday speech, which he has honed for his own campaign, warning of the ills of Republican control of government at the state and federal level and painting himself and New York State as the bulwark against Trump and the many threats his administration has levelled -- against women, immigrants, the LGBTQ community, Puerto Ricans, for instance.

“Elections matter. This one really, really matters,” Cuomo said, speaking of a broad disaffection among the electorate, on both sides of the aisle. The governor and Gounardes also signed a pledge, mostly similar to the one from Monday but including a focus on New York City issues such as a promise to pass speed camera legislation for school zones and expanding rent stabilization, and not including Long Island-focused planks like the LIRR and demanding more MTA funding from the city.

The September 13 primary saw a massive increase in turnout among Democratic voters, which many have cited as evidence of an ongoing and growing “blue wave” that is similarly boosting Democratic candidates across the country and expected by some to come crashing down upon Republicans on Election Day, November 6. But Cuomo’s own interpretation has differed somewhat, including when he dismissed the notion of a progressive wave the day after he won his primary, despite the fact that his under-funded opponent received more than 500,000 votes (to Cuomo’s nearly 1 million).

“I don’t like the expression the ‘blue wave’, because the ‘blue wave’ suggests its partisan,” Cuomo said at Tuesday’s rally in Bensonhurst, “that it’s Democrats who are offended. It’s not just Democrats who are offended...What this president is doing is not anti-Democratic, it’s anti-American...This is not a blue wave, my friends. This is a red, white, and blue wave.”

Last month, in the immediate aftermath of his primary win, just as he had done a few months after Donald Trump assumed office, Cuomo rallied the troops, but to his tune. “[T]he truth is this president and his extreme conservative colleagues have declared war on the State of New York. They are attacking our rights, our values, and our economy,” Cuomo said at a September 18 Democratic rally billed as an effort to relaunch the general election campaign to swing the state Senate and help flip the U.S. House. For nearly 20 minutes, Cuomo, newly invigorated from his primary win, inveighed against the “extreme conservative freight train” from Washington running roughshod over New Yorkers, and promised “more organizing, more mobilizing” to capture the energy of the Democratic base.

“[W]e’re gonna take this energy that we now have and we’re going to build on this energy,” he said. “It’s not going away...There’s a whole new Democratic movement. They’re responding to what we did and they’re responding to what they want to do by stopping this threat in Washington. And we have to build on that energy.”

A spokesperson for Cuomo’s campaign said he plans to personally raise funds and campaign for ten Democratic candidates running against sitting Republican congressional representatives -- he’s already sent each of them a maximum donation of $2,700 through a federal political action committee, Cuomo NY Take Back the House. The candidates include Perry Gershon, Liuba Grechen Shirley, Max Rose, Antonio Delgado, Tedra Cobb, Anthony Brindisi, Tracy Mitrano, Dana Balter, Joe Morelle and Nate McMurray. Politico New York reported last month that the broader effort Cuomo had promised had yet to materialize as he seemed more preoccupied with his own primary challenger, actor and education activist Cynthia Nixon. He has so far only held a fundraiser for Brindisi.

Among the Democratic state Senate candidates who have Cuomo’s support are some who are challenging incumbents and others running for open seats. He is also bolstering two Democratic Senators facing Republican challengers. They include Monica Martinez who is challenging Dean Murray in District 3; Lou D’Amaro, who is challenging Sen. Phil Boyle in District 4; Jim Gaughran, who is challenging Sen. Carl Marcellino in District 5; Anna Kaplan, who is challenging Sen. Elaine Phillips in District 7; Peter Harkham, who is challenging Sen. Terrence Murphy in District 40; Karyn Smythe who is challenging Sen. Sue Serino in District 41; Gounardes challenging Golden in District 22; and Democratic Senators John Brooks, who is being challenged by Massapequa Park Mayor Jeff Pravato in District 8, and Todd Kaminsky, who is being challenged by former Nassau lawmaker Francis Becker Jr. Cuomo’s campaign has donated the maximum primary limit of $7,000 to all those candidates, save for Gounardes and Kaminsky. If he decides to do so, Cuomo could direct another $11,000 to each candidate’s campaign for the general election.

The campaign is currently in the process of scheduling fundraisers for the congressional candidates and has already set up eight events to support the state Senate contenders, starting on Wednesday, October 3, with a fundraiser for Smythe. Fundraisers are scheduled to support Gounardes and D’Amaro on October 9; for Martinez on October 12; for Brooks and Kaminsky on October 15; for Harckham on October 21; and for Kaplan on October 22.

But it’s not only campaign cash that Cuomo will corral for the candidates. His campaign infrastructure and the State Democratic Party’s assets are being put to use to raise name recognition for the candidates and to get voters to the polls. Some of the congressional seats also overlap with the competitive Senate districts, giving Cuomo the ability to kill three birds with one stone as he also campaigns for his own reelection, perhaps without making it too obvious. The governor is facing a handful of challengers led by Republican nominee Marc Molinaro.

According to the Cuomo campaign spokesperson, there are more than 25 state party staffers in the field, training and engaging Democrats on the ground and leading Get Out The Vote efforts across the state. In congressional districts 1, 11, 19, 22 and 24 -- the five identified by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee under their ‘Red to Blue’ campaign effort -- the state party has sent campus organizers to rally young people, and in major metropolitan regions, organizers are recruiting volunteers to aid in those battleground districts. The party is also using digital and social media and data analytics to bolster outreach.

There’s also the tried-and-tested method of campaign mailers, in which the State Democratic Party has invested hundreds of thousands of dollars, the campaign spokesperson said, urging voters to support candidates including Rose, Brindisi, Gershon, and Delgado. (At this point there have been no other controversies with such mailers beyond the one that has dogged Cuomo and the party that sought to falsely tie Cynthia Nixon to anti-semitism in the final weeks of the primary.)

The party and campaign together spent millions on its statewide primary ticket -- to set up field offices and organizers -- and the campaign spokesperson said they would expand on that infrastructure for the general election.

Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul, who prevailed in last month’s primary over challenger Jumaane Williams, a Brooklyn City Council member, is also leading her own parallel effort to support female candidates for Congress and State Senate. “Republican control of Congress and the New York State Senate has been a disastrous disappointment for all New Yorkers, especially women and middle class families,” Hochul said in a September 28 statement, launching the general election effort. She announced her support for four Congressional candidates -- Grechen Shirley, Cobb, Mitrano and Balter -- and five State Senate candidates -- Martinez, Kaplan, Smythe, Jen Metzger and Jen Lunsford.