‘Voters of Manhattan Responded to the Message of Marrying Fairness and Safety’: Alvin Bragg Discusses His Lead in the District Attorney Primary

Alvin Bragg on the campaign trail (photo: @AlvinBraggNYC)

Alvin Bragg, the current frontrunner in the Manhattan District Attorney Democratic primary election, said during an appearance this past week on the Max Politics podcast that he is pleased with how voters responded to his campaign and expressed cautious optimism that his lead will hold when tens of thousands of absentee ballots are counted in the coming weeks.

“I feel good,” Bragg told host Ben Max of Gotham Gazette. “I feel that the voters of Manhattan responded to the message of marrying fairness and safety that I’ve been living for almost 50 years, I’ve been working on for more than 20, and I’ve been talking about on the campaign trail for quite some time now.”

Bragg emerged on top of the eight candidates vying to be the Democratic nominee for Manhattan DA in the fall general election after a tally of in-person votes late Tuesday night. If elected, Bragg, who most recently served as the Chief Deputy Attorney General for New York State, will be the first Black person ever elected to the office, which is Manhattan’s chief prosecutor and state law enforcement official.

The race, still too close to call, has Bragg ahead of Tali Farhadian Weinstein by 7,265 votes, or 3.42%, with almost all of the in-person vote tallied from the early voting period and primary day. About 212,600 in-person votes were tallied, and Bragg received just under 72,000, while Farhadian Weinstein received almost 64,700.

Despite Bragg’s sizable lead, the outcome of the race may hinge on the absentee ballot count -- as of Sunday night, the Board of Elections had received more than 39,000 absentee ballots back from Manhattan Democrats (more than 59,000 were sent out by the BOE upon request from eligible voters).

"We all knew going into today that this race was not going to be decided tonight and it has not been," Farhadian Weinstein said, in part, on primary night. "We are down about 3.9 percent with tens of thousands of ballots from today and about 50,000 absentee ballots left to be counted. And so we have to be patient."

Unlike all of the city government primaries on the ballot this year, the Manhattan District Attorney race is a state office, so ranked-choice voting was not at play. There are no runoffs, either, so whichever candidate gets the most votes wins the primary. The winner of the Democratic primary is all but certain to win the general election given Manhattan’s overwhelming Democratic tilt, but there will be competition from Republican nominee Thomas Kenniff.

While on the campaign trail, Bragg found himself comfortably between multiple leftist, de-carceral candidates—such as current third-place candidate Tahanie Aboushi, who trails Bragg by nearly 50,000 votes—and those further to his right, who took more of a hard-line stance on crime and safety, including Farhadian Weinstein.

After Bragg, Farhadian Weinstein, and Aboushi, the order among the other Democratic candidates in terms of in-person vote totals is Lucy Lang, Diana Florence, Liz Crotty, Eliza Orlins, Dan Quart. Final results will be determined by how the absentee votes break.

While Bragg was circumspect during the Wednesday podcast appearance, his campaign has since used more stark language, with an email to supporters on Sunday signed by Bragg himself with the subject line "Protecting our victory," and seeking to raise funds to help pay for legal battles that may ensue. "Thanks to you, we did something historic on Tuesday," the message says, in part. "While the math overwhelmingly shows we were victorious, our billionaire opponent has not conceded and there are rumblings of coming court challenges." Farhadian Weinstein's wealth became a focal point of the race, especially after she put more than $8 million of her own money into her campaign.

Bragg credits his lead to his campaign’s ability to balance safety and reform, as many voters have encountered both public safety issues and unfairness in the law enforcement and criminal justice system.

“The key language we tried to drill down on during the campaign is how we respond to those public safety issues, right,” he said. “I’ve seen this failure of this, you know, ‘law and order,’ ‘war on drugs’ approach, which locks up whole communities. That’s not true public safety. That’s just bad public policy."

In light of the recent increase in gun violence in the city, Bragg said he plans to enhance gun intervention programs, as well as follow money and contraband to find the most culpable criminals. Overall, he said, the DA’s office needs to pair a community-based public safety model, which can range from community violence interruption programs to hospital visits with victims of gun violence, with smart and effective prosecution.

Additionally, reforming the larger law enforcement system, Bragg said, would free up the DA’s office to focus on the pressing and significant threats to public safety.

“I think there’s a yearning in Manhattan to fundamentally reform our system...,” Bragg said. “We have gone throughout the borough and heard, in all corners of the borough, not just up here in Harlem or on the Lower East side, deep concern about police accountability. Deep concern about the types of offenses that we arrest people for that have little to no public safety benefits.”

One example of enforcement for these types of offenses is the NYPD prioritization of arrests for untaxed cigarette sales, he said. Tracing the sales back to shipments of untaxed cigarettes and prosecuting those in charge of shipments, according to Bragg, would help the DA’s office to truly hold the funders of criminal activity accountable and reduce any problems that occur at the community level.

He also spoke about his father’s struggles with substance abuse and how New York City is indisputably in the midst of a mental health crisis. Bragg said the DA’s office needs to put resources to good use to address the crisis and lean into substance abuse diversion programs.

Bragg criticized law enforcement criminalization of poverty, and asserted that the government should turn to other methods to address issues like homelessness.

“Whether it’s the homeless person that’s taking up two seats on the subway—a real case from this past summer that was prosecuted—or the homeless person who the DA’s office recommended a sentence of internment of five to 10 years for, you know, buying food or toothpaste with a counterfeit bill,” he said. “Those are not criminal matters for me, and we need to use other tools in the government toolkit to address those and save our criminal resources for things that are really what New Yorkers are up thinking about, talking about. True public safety issues.”

When asked about any parallels with mayoral primary frontrunner Eric Adams, a former NYPD captain, Bragg noted they appear to have some policy differences around the role of police, though he did not get into specifics, but acknowledged similarities around how they both highlighted personal experiences in pitching voters on their visions for justice and safety. Bragg, who grew up in central Harlem, said that those in the public square must continue to share their personal narratives as these stories hold power and resonate with voters.

“When we do that, we encourage others to tell their story and we develop public policy around real life experiences...,” he said. “ That power of narrative, and really meeting people where they are and talking about everyday experiences, I think is potent and I really respect Eric for bringing those forward.”

[LISTEN: Max Politics Podcast: Alvin Bragg on His Lead in the Manhattan DA Primary]

[WATCH: Decision NYC: Alvin Bragg Discusses His Campaign for Manhattan District Attorney (from March)]

***

by Megan Kelly

@GothamGazette

Ben Max contributed to this story.

State Allows Psychiatric Facilities to Forcibly Vaccinate Patients Against COVID-19

(photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The New York State Office of Mental Health quietly issued guidance in April allowing psychiatric centers to vaccinate patients for COVID-19 over patient objections and without a court order in a unusual break from treatment protocols. The policy makes psychiatric patients in state custody one of the only adult populations in New York subject to forcible vaccination.

The guidance, issued April 22, is a "clarification" giving hospital staff discretion to administer the vaccine without consent, an intrusive action clinical staff and lawyers working with patients say is unnecessary and alarming. It came more than four months after people living in state-run inpatient facilities became eligible for the vaccine and despite uptake being roughly equivalent to the statewide adult vaccination rate.

A spokesperson for the Office of Mental Health (OMH) told Gotham Gazette the agency has not followed through with any forced vaccination though at least one facility had initiated the process before patient representatives objected. OMH would not say how often facilities have attempted to force vaccinations or why the guidance was needed.

The news comes over a year after the coronavirus pandemic swept through OMH psychiatric facilities and disproportionately killed patients living there in close quarters with limited covid safeguards. While OMH said the policy has not led to any vaccination over objection, multiple attempts have been made by staff and it remains on the books. The state psychiatric system, where patients are held involuntarily, has been plagued for decades with due process concerns.

There has been virtually no public oversight of conditions in OMH psychiatric centers by either mental health committee in the State Legislature since the pandemic began.

Under the guidance sent to facility leadership from OMH headquarters, psychiatric centers "may pursue the usual treatment over objection process for routine medical procedures which do not require informed consent."

That means, unlike with psychotropic medications and medical procedures that are typically deemed by the hospital to require "informed consent" (itself a grey area) and a judge's sign-off, hospitals can pursue an internal administrative procedure and possibly avoid a court order to vaccinate a patient against their wishes. If it does get to court (only after multiple internal appeals), the burden of proof is on the patient to show the administration is incorrect or abusing its discretion, a playing field deferential to OMH, lawyers said.

Any medical treatment over objection is rare. In general, hospitals pursue treatment over objection for patients refusing to take antipsychotics and other psychiatric medication and almost never for something as mundane as a vaccine, according to people with knowledge of the facilities. If they do, they normally need a court order before administering any treatment thanks to a 1986 Court of Appeals ruling, Rivers v. Katz, that included treatment choice among an individual's due process rights.

According to one clinical staff member at an upstate OMH facility, employees sometimes discuss the possibility of seeking treatment over objection for medical purposes like kidney treatment or insulin for diabetes, but it usually comes to nothing.

“I’ve never heard of that actually going forward,” they said over the phone, speaking anonymously because they weren't authorized to talk with press. No lawyer or the clinician Gotham Gazette spoke with had ever heard of vaccines being given over objection to psychiatric patients in state institutions.

“Even if you are mentally ill, you are still able to make basic decisions about your medical treatment…To some extent everybody is allowed to make a bad decision for themselves. They might not be able to represent themselves in court, or may not be culpable of a crime but they’re still able to say, ‘I want a treatment’ or ‘don’t want a treatment,’” the staff member said.

But the April guidance says hospitals can unilaterally seek treatment over objection without a Rivers hearing under a more limited protocol used for "routine" and ostensibly non-invasive regimens. In these cases, appeals by the patient must go through multiple levels of hospital leadership all the way up to the OMH Commissioner before they can go before an external court. That is a matter of attrition and the objection may never reach a judge, lawyers say.

The agency has denied any vaccinations over objection have taken place under the guidance. "OMH has not vaccinated anyone over objection and we would not do so without a court order. The April 22 clarification is for patients without capacity who are NOT objecting," wrote OMH spokesperson James Plastiras in an email. He later clarified, after an inquiry, that the guidance did include instructions on vaccination over patients' objections: "The last line of the guidance points out that this does not pertain to patients with impaired decisional capacity who object. In those instances, facilities were directed to follow normal procedures for treatment over objection. In any case, OMH has not vaccinated anyone over objection."

OMH has not said why the guidance was needed or how many patients may have been targeted for the procedure. One facility did try to vaccinate patients over their objections, according to Plastiras, but voluntarily ended the process. People with knowledge of the situation said several patients were in line to be injected before the facility pulled the plug after lawyers and clinical staff objected.

"While an OMH facility did seek treatment over objection for patients with impaired decisional capacity as permitted under 14 NYCRR § 27.8, those notices were subsequently withdrawn. No OMH patients or clients have been vaccinated over their objection," Plastiras wrote. He did not say which facility or how many patients were targeted.

About two thirds, 68%, of the 3,390 people living in in-patient state psychiatric facilities have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, according to OMH as of June 15, compared to 70% of adult New Yorkers statewide. The rate among the roughly 12,500 OMH facility staff is 72%.

"As far as the patients are concerned, a lot of them saw their friends die. They were ready for the vaccine the day it was available," the clinician said.

Treatments over objection orders can be traumatic and in some cases dangerous. Often patients acquiesce to the treatment, which must be in the form of an injection. But when they refuse, they are either held down in their beds by hospital staff or put into a restraint bed and moved to a seclusion room.

“The preferable way is to have staff physically restrain because it’s much faster…it almost always happens in their bedroom, on the bed. But if a patient is fighting…then they do use a restraint bed,” the clinician said. From their own experience working with patients, they estimated about one in five cases of refusal require restraint and only a fraction of those are seriously violent.

The only similar situation is the state Office for People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD), a branch of OMH separate from psychiatric centers. OPWDD expanded the mandate of so-called Informed Consent Committees -- administrative bodies established at each provider to oversee consent for certain procedures -- to include COVID-19 vaccines in cases where clients could not consent because of a developmental disability and lacked a designated surrogate.

"For those who do not have another authorized surrogate decision-maker to assist them, Informed Consent Committees have been authorized to provide informed consent for the COVID-19 vaccine pursuant to regulation and based on each person’s wants and needs,” wrote OPWDD spokesperson Jennifer O’Sullivan in an email. She did not confirm whether ICCs have been used in cases where clients actively refused a covid inoculation.

The vaccination rate of people living in OPWDD residential facilities was 86.5%, according to O'Sullivan, well above the state average and dwarfing the 38.2% of OPWDD clients living at home or in their community. The office did not have data on the number of clients vaccinated through an ICC.

***

by Ethan Geringer-Sameth, reporter, Gotham Gazette

@GeringerSameth @GothamGazette

Max Politics Podcast: Alvin Bragg on His Lead in the Manhattan DA Race

Alvin Bragg (photo: @alvinbraggynyc)

June 23, 2021 - Max Politics Podcast: Alvin Bragg on His Lead in the Manhattan DA Race

Alvin Bragg, leading the Manhattan District Attorney Democratic primary election after the initial tally of in-person votes, joined the show to discuss his campaign and platform.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think -- on Twitter @TweetBenMax . You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org.

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Candidates for Manhattan District Attorney on Ending the 'Trial Penalty'

Courtroom (photo: @nakrnsm)

Earlier this year, a report on use of the “trial penalty” -- the increased likelihood that a defendant, if proven guilty at trial, will face a harsher sentence than if they had opted into a plea deal -- in New York showed that its practice by district attorneys threatens the constitutional rights of defendants, limits law enforcement transparency, and weakens the overall integrity of the justice system.

The report, from the New York State Association for Criminal Defense Lawyers, in cooperation with the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, then prompted the organizations to ask related questions of this year’s candidates in the wide open and highly-competitive and -consequential race to be the next Manhattan District Attorney. An eight-candidate Democratic primary for the seat being vacated by District Attorney Cyrus Vance, a Democrat, is being voted on this month by eligible Manhattanites.

The trial penalty is widely considered to be a driving force behind mass incarceration and wrongful conviction, serving as a loophole through which law enforcement can escape a vital check on its overreach. Its use can be driven by a number of factors including mandatory minimums and overcharging by lawyers who, faced with burdensome caseloads, want to save time by avoiding trials while also racking up as many convictions as possible.

Released in late March, the report indicated that 94% of surveyed criminal justice practitioners across New York State acknowledged the presence of the trial penalty as a component of criminal proceedings in their county. Those responses were supported by data showing that in 66% of cases sampled, defendants had experienced a trial penalty.

The two organizations reached out to candidates in the race for Manhattan District Attorney for specific answers on how they planned to approach the issue if elected to the office, the top prosecutor and law enforcement official in Manhattan, and a position of national prominence.

Responses were provided by Democratic candidates Tali Farhadian Weinstein, Alvin Bragg, Tahanie Aboushi, Eliza Orlins, Dan Quart, and Lucy Lang, as well as Repuplican candidate Thomas Kenniff, who is awaiting the results of the primary before going head to head in the November general election. Democrats Diana Florence and Liz Crotty did not respond.

In their responses, nearly all of the candidates signaled opposition to mandatory minimums, but only Aboushi, Orlins, Quart and Farhadian Weinstein explicitly indicated that they would advocate for their repeal once in office. A universal refrain throughout the questionnaire was a need to establish a “Conviction Integrity Unit” or a taskforce of that kind by another name to specifically review wrongful convictions and instances of excessive sentencing. Candidates also reached consensus on the need to eliminate the use of bail as a means to coerce defendants into taking pleas as well as support for limited judicial oversight of plea bargaining and “second looks,” or the right to petition for a lesser sentence after a period of time.

Tahanie Aboushi, a civil rights attorney, outlined a plan to guarantee defendants their Sixth Amendment right by disclosing all discovery promptly, ensuring attorneys are fully compliant with the letter of Brady and open file, enacting a no-call list so witnesses, especially those in law enforcement, remain credible, and dismissing cases where law enforcement has violated constitutional rights.

Taboushi drew on personal experience in her response, revealing that her mother was charged to coerce her father into taking a plea deal. “She was nothing more than leverage,” Aboushi wrote, “the prosecutors did not care about what would happen to me or my siblings.”

When prompted about the underlying issues that perpetuate the trial penalty -- specifically unrestricted prosecutorial charging discretion, mandatory minimum sentencing statutes, and discretionary use of enhancements for prior convictions, Aboushi promised her tenure as district attorney would be marked by an “aggressive declination policy.”

She aims to charge the least serious offense possible and when enhancement in sentencing is discretionary, promised to never advocate for its application. She also presented plans to end the Early Case Assessment Bureau where overcharging is said to often take place, instead supervising each case and requiring approval for prosecutors wanting to deviate from her policies.

Regarding previous cases in which the trial penalty was employed, Aboushi supports use of a Conviction Integrity Unit to review wrongful convictions, cases involving police or prosecutorial misconduct, extreme sentencing, or sentencing that “has long since ceased having any arguable public safety component.” The unit would then focus on remedies by requesting new trials, reducing sentences, and authoring reports that explore the major drivers of wrongful conviction -- sentence length, gender, race, and criminal history.

With respect to the disproportionate likelihood of Black defendants under the age of 25 to receive the trial penalty, Aboushi indicated that her declination policy would extend to charges involving young adults, and that her office will focus on expanding access to family court and Youthful Offender status for any young person who does wind up exposed to the adult judicial system.

“A guiding principle of our office will be that we must do all we can to stop the patterns of racism and bias that have been ignored for far too long,” Aboushi wrote, promising to stop prosecution on certain types of offenses if bias is proven in the application of the law.

Alvin Bragg, a former federal prosecutor and top deputy to the New York State Attorney General, explicitly stated in his response that he would not allow sentence recommendations after a hearing or trial to be longer than those offered prior. The district attorney office under his control would not, he said, rely on traditional metrics and would instead shift focus to a more holistic equation involving a review of the cost and racially-disparate impacts of incarceration as well as the effects on recidivism, public safety, and reentry.

On the underlying factors contributing to use of the trial penalty Bragg proposes minimizing pretrial detention, which can lead to more coercive plea bargaining practices and using incarceratory sentences in only the most extreme cases. He stopped short of promising an abolition to mandatory minimums, outlining the restrictions of the office, which bar him from doing so, but advocated using misdemeanor charges to avoid them and voiced opposition to sentence enhancement.

Bragg also shared that his plan to avoid violation of Brady -- a legal statute ensuring open disclosure of all exculpatory evidence -- involves a culture shift in the office away from “winning” and towards true justice.

Bragg plans to deal with previously-tried cases by abolishing the current Conviction Integrity Unit and replacing it with his own Free The Wrongfully Convicted Unit which will start from scratch. In response to the racially-disparate use of the penalty he reiterated his status as the only Black candidate in the race, laying out plans to track disparities in real time and publish comprehensive data throughout the criminal process, and engaging “all the diverse communities within Manhattan.”

Lucy Lang, a former assistant district attorney in Manhattan and more recently head of a criminal justice institute, stressed in her response the importance of dealing with the “extensive backlog” of cases as a means of securing the Sixth Amendment rights of New Yorkers. On the driving factors of the trial penalty Lang promised to take mandatory minimums into consideration before indictment and to have a default policy against using conviction enhancements. Her response to any potential violations of Brady involves establishment of a new position -- the Prosecutorial Ombudsman. This would be an independent attorney acting as an oversight officer, reviewing allegations of misconduct and either submitting ethics complaints to the New York State Bar Association or identifying individual lawyers to the District Attorney for discipline or dismissal accordingly.

Regarding previous convictions, Lang plans to create a new unit -- the Retroactive Review Unit -- which would review cases with hopes to reduce “extreme” sentences, account for growth while incarcerated, and improve reintegration. In response to racism in sentencing and the trial penalty, Lang proposed a number of in-office changes, requiring staff to be trained in the history of harm between the district attorney and communities of color as well as implicit bias. She promised to regularly visit incarcerated New Yorkers and to require all employed attorneys to participate in the Inside Criminal Justice course that places district attorney staff members alongside incarcerated students to study criminal justice and write policy together.

Eliza Orlins, a former public defender until jumping into the Democratic primary for district attorney on a decarceral platform, also advocates for plea deals to be made on the record and promised that sentences offered in bargaining would match those recommended after trial. She leaned into the political powers of the office as well, vowing to use the “bully pulpit” to abolish court fees. On the underlying causes of the trial penalty, Orlins proposed eliminating “unrestricted prosecutorial charging discretion” and is in favor of working with legislators in Albany to abolish mandatory minimums. She says the issue of discretionary use of enhancements for prior convictions is more nuanced but needs to be reformed in the way it is applied to defendants of different races.

On violations of Brady, Orlins’ was straightforward: evidence will be offered immediately to defense, the right to prosecutorial review should be waived. She wants to establish a Conviction Review Unit with a broader approach, and promises to develop a notification system once in office that will identify when cases veer from policy. Those policies would warn against overly long sentences, sentences that deviate from the pretrial offer, and criminal charges not “preceded by an attempt at diversion.” Orlins indicated she would also use the CRU to address racial disparities and produce data analysis on how to identify them within the system. She also promised not to prosecute drug possession cases, which she says are often levied inequitably in communities of color.

Dan Quart, a New York State Assembly member, is proposing to fight the trial penalty by providing defense with a full, complete, and relevant discovery so all parties have the same information. He also promises greater flexibility and transparency during the plea bargaining process as well a commitment to decline prosecuting multiple misdemeanor charges and downgrade certain penal law offenses from felonies to misdemeanors. On the underlying causes of the trial penalty, Quart assured he would not as DA rely on unrestricted prosecutorial charging discretion or request cash bail. He also cited his experience in the legislature as uniquely qualifying for a working relationship aimed at eliminating mandatory minimums.

In reference to violations of Brady, Quart argued that by declining to prosecute low-level offenses, he could free up resources to support assistant district attorneys in complying with discovery rules and securing thorough and effective work. On retroactive review of convictions, Quart doubled down on criticism of current Manhattan DA Vance and promised to work with the Legislature to reform penal law Section 440, which he argues would give greater flexibility to defendants claiming to be innocent or that their convictions were secured improperly.

The racial disparities evident in use of the trial penalty need to be public knowledge, Quart argues, joining other candidates in the promise to share data on charging decisions and plea offers. He also set himself apart by vowing not to use the “enterprise statute” for drug sweeps or to use surveillance-based technology, citing both as tools that disproportionately target young men and boys of color.

Tali Farhadian Weinstein, a former federal prosecutor and general counsel to Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez, stressed the need for robust investigation to secure a fair trial and dependence on the discovery changes New York enacted in 2019 to ensure defendants have the vital information needed to exercise their Sixth Amendment rights. To address the underlying causes of the penalty, Farhadian Weinstein says she will staff the office’s Early Case Assessment Bureau with only senior prosecutors whose judgement is more easily trusted in the charging of offenses that have been disparately applied. She also promised to support legislation eliminating mandatory minimums and sentencing enhancements, favoring instead a system that “allows for more discretion for prosecutors and judges, and avoids the imposition of severe penalties in cases in which public safety does not require such sentences.”

Farhadian Weinstein’s responses were generally shorter than her peers, making succinct points about “early and open discovery” regarding Brady violations and advocating “vigorously” for the creation of a “second look mechanism” meant to review and correct excessive sentences. To combat racial disparities, she committed to partnering with outside organizations who could review data on the differences in charging and sentencing. On sentencing generally, Weinstein promised to require the assistant district attorney to seek the minimum sentences, with supervisory approval necessary in order to seek a higher sentence.

Thomas Kenniff, a former prosecutor and military veteran is the sole Republican candidate in the race. In response to the survey, Kenniff promised to address the trial penalty by “charging crimes proportionately as opposed to tactically.” His solution relies on an increased budget for the DA’s office and institutional defense providers, calling it “naive” to think a burdensome caseload doesn’t add pressure to keep cases out of trial, and arguing that appointing additional judges and creating additional trial parts will also aid the process.

On the issue of underlying factors, Kenniff states that both sentencing enhancements based on prior convictions and mandatory minimums have a place in crime deterrence but need to be sufficiently reviewed by supervisors and should not be used for upcharging. On Brady violations and transparency, Kenniff says his philosophy has always been “when in doubt, turn it over” and that the digital resources put out by the DA’s office could be made more user friendly for defense attorneys.

Kenniff is a proponent of the use of the Conviction Review Unit to look at previously tried cases but says he will “be respectful of a court’s autonomy in matters of sentencing,” while reviewing instances where defendants were sentenced disproportionately, seeking redress “where appropriate.” In response to the data proving racial disparities in application of the trial penalty, he promised to evaluate each individual case and take into account all factors in mitigation at sentencing, ensuring there is supervisory approval in place before a sentencing recommendation is made to a court.

The final section of the questionnaire prompted candidates to answer a series of yes or no questions. All seven -- six Democrats and one Republican -- answered in the affirmative when asked whether they would instruct their ADAs to provide full access to discovery and not just the potentially exculpatory evidence as well as whether they support proportionality between pre-and post-trial sentencing. Nearly the same consensus held true for a question on support for the repeal of NYCPL § 220.10(5), which limits the ability to resolve a case by pleading guilty to a lesser charge, with the exception of Farhadian Weinstein, who said she needed to study the proposal further.

All candidates also signaled support for an increase in public defense funding, and an express prohibition within The Code of Judicial Conduct of retaliatory or vindictive sentencing for a defendant who rejected a plea deal and went to trial. When prompted about whether prosecutors should be prohibited from conditioning plea offers on a waiver of statutory or constitutional rights necessary for a defendant to make an informed decision on whether to plead guilty all candidates replied in the affirmative except for Farhadian Weinstein, who again said she needed more information.

A slightly more split reaction came on a question about whether it should be deemed unethical for a prosecutor to seek a higher sentence compared to a pretrial offer based on if the defendant litigates their statutory or constitutional rights, including the right to trial. Aboushi, Bragg, Lang, Orlins, and Quart all responded yes. Keniff said not in all cases, and Farhadian Weinstein said it also might be appropriate in some cases.

***

by Anna Kaufman

@GothamGazette

After Cuomo Veto and Pledge to Revisit, No New York Movement on Wage Theft Bill

Gov. Cuomo with workers (photo: Kevin P. Coughlin/Governor's Office)

*This story was published in partnership with New York Focus.*

Since 2014, Jin Gou Ke, an immigrant from China's Fujian Province, has worked as a delivery worker for Tasty Hand-Pulled Noodles in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Paid a pre-tip salary of just $3 per order, far short of the city’s minimum direct cash wage of $12.50 an hour for delivery workers, he worked long hours to earn enough to pay for the room he rented in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Typically, Ke said, he worked 11 hour days, 7 days a week, with just one day off each month.

Work conditions were unfriendly: during the height of the pandemic, he said, he was illegally barred from using the restaurant’s bathroom, forcing him to relieve himself in a nearby public park. He knew he was being paid and treated unfairly, he said, but was still happy to have work.

“I’m just working, so I can earn a living and so I can eat,” he told New York Focus. “As long as I keep working, I’m fine.”

After the pandemic hit, the restaurant closed and Ke found himself temporarily out of a job. When it reopened in July, he was grateful to be back to work. But the relief was short-lived: by December, Tasty Hand-Pulled Noodles was increasingly relying on food delivery apps, and told Ke they no longer needed his services. Ke was fired—and never received the total wages owed to him, he said.

“I worked so hard for so many years and they treated me so bad,” Ke said. “ I exposed myself to the virus so many times going out every day and I did so much for them. It’s not right.”

Rampant wage theft was already supposed to have been dealt with. Last year, a coalition of workers’ centers, elected officials, and activists rallied around the Securing Wages Earned Against Theft Bill (SWEAT), which proponents say would give workers more power to fight back against exploitative employers.

Governor Andrew Cuomo vetoed that legislation in 2020, citing “technical aspects” that made it constitutionally fraught. In his veto message, the governor pledged to enact provisions achieving the same goals in this year’s budget. “I am constrained to veto this bill but I look forward to enacting the necessary protections for workers very soon,” he wrote.

Yet, flouting that commitment, the governor omitted wage theft entirely from his 2021 executive budget. Freeman Klopott, the governor’s budget spokesperson, declined to comment for this story. Klopott directed New York Focus to the state Department of Labor. A spokesperson there did not respond to questions about Cuomo’s inaction on wage theft, but said in a statement, “the DOL continues to aggressively crack down on bad actors who have wage and unemployment insurance violations.”

“It's been almost a year and a half, and he has done nothing,”said Sarah Ahn, an organizer with the Flushing Workers Center, which serves predominantly Chinese and Korean workers. “Meanwhile, workers are suffering more than ever.”

Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal, a Manhattan Democrat who co-introduced the bill along with State Senator Jessica Ramos, a Queens Democrat, agreed. “Without action to address wage theft, hardworking New Yorkers have become even more vulnerable to wage theft during this pandemic,” she said. “That's why it's vital that we pass the SWEAT bill again this session.”

Wage theft was not included in the adopted state budget, either—despite many prominent wins for progressives.

“Stuck waiting to be paid”

Even before the pandemic, as much as $1 billion in wages were stolen from New Yorkers annually, according to a 2014 study by the U.S. Department of Labor. A disproportionate number of the victims are undocumented workers, whose precarious legal status can make them especially vulnerable to wage theft and other workplace abuses.

Four workers centers across the state told New York Focus that they have seen a significant increase in wage theft cases since the start of the pandemic last March, corroborating recent research finding that low-wage workers face an elevated risk of wage theft during periods of high unemployment.

“Employers were using the pandemic as an excuse to not pay workers,” said Glendy Tsitouras, an organizer with the Workers Justice Project, a Brooklyn-based worker center that serves day laborers and domestic workers. “They would tell workers that something happened and that they will pay next week—but that never happened.”

In April of 2020 alone, Tsitouras said, her organization was flooded with between 30 and 35 cases. Pre-pandemic, they typically received around 15 cases a month.

Sarah Ahn described wage theft as a systematic way to maintain a permanent and insecure low-wage labor force.

“When we talk about minimum wage increases, a lot of workers think, ‘it doesn’t matter, my bosses don’t care what it is, they won’t pay me,’” she said. “Undocumented workers don’t have a right to work. They are literally an underclass that is criminalized for working. If workers speak out, they are threatened with ICE.”

Osmar Figueroa, a client of Tsitouras, said he was fired from his construction job with Cassway Contracting in December after he demanded nearly $4,000 in unpaid wages.

A day laborer from Guatemala, he and 14 other construction workers labored nine hours a day, six days a week at a construction site in Manhattan, Tsitouras said. They were paid the first and third week, he said, but Cassway, a construction company, claimed there was no more money to pay them at the end of December, she said. When they refused to continue working without being paid, Figueroa said, all 15 men were fired and replaced with a new batch of workers.

Out of a job and without cash, Figueroa struggled to make rent, buy food, or send money back to Guatemala.

“It was harder because it was the holidays and we didn’t have money,” he said. “My co-workers have kids, they have families and they weren’t able to buy gifts for them. They couldn’t celebrate Christmas because they didn’t have money.”

Guillermo Cruz, a Nicaraguan day laborer with KML Restoration Corp, a construction company, described a similar experience. After one of the owners of the company died of Covid-19 in May, the company claimed it was unable to pay its 10 employees, he said.

Collectively, KML Restoration owed the workers $20,000 in wages, Cruz said. Although Cruz worked through the pandemic, risking his health, he was left with little to show for it.

“It was terrible because we were exposed to the virus, but we did the work for the company and they used us to finish the work and not pay us,” he said. “I feel frustrated because I need to feed my family and pay my rent. I’m just stuck waiting to be paid.”

In Buffalo, Mary Lister, an organizer with the Queen City Workers Center, is working with the former staff of the Hotel Henry Urban Resort and Conference Center, who are suing to reclaim nearly $800,000 in unpaid wages. In February, the hotel abruptly closed without settling up with its staff.

“We have definitely seen a huge increase in the number of workers who are contacting us during the pandemic,” said Lister. “Many of them, like the workers at Hotel Henry, had first contacted a lawyer before contacting the workers center, but after seeing the limitations of the messed up legal system where even if they win, employers will be able to hide their assets, [initially decided not to file lawsuits].”

Cassway Contracting did not respond to New York Focus’ repeated inquiries. KML Restoration Corp could not be reached for comment. Hotel Henry declined New York’s Focus request for comment.

Amy Liu, manager and daughter of the owners of Tasty Hand-Pulled Noodles, denied the allegations and said that the establishment has never employed Ke or any independent delivery worker.

“I never know this guy. I don’t know who you are talking about,” she said over the phone. “I never hired a delivery guy.”

Told that New York Focus reviewed checks made out to Ke from Tasty Hand-Pulled Noodles, Ke declined to comment. When reached again and offered another opportunity to comment on Ke’s allegations, Liu said, “I just know that he is a liar. That’s it.”

“Don’t have a shot at winning”

Even when workers file and win lawsuits against employers and are awarded stolen wages, they are often left unable to collect the money they are owed. As cases make their way through the courts, employers can take complicated measures to hide assets, for example closing their business and then reopening under a different name, to avoid having to pay up.

SWEAT, which was reintroduced by Assemblymember Rosenthal in January after Cuomo vetoed the original bill, would make it harder to evade court judgements by allowing a lien to be placed on an employer’s business or assets while a case is being heard, preventing fraudulent transfers and closures. To file for a lien, workers would have to show evidence in court that they are likely to win a wage-theft case.

The strategy is modeled on New York’s existing mechanic’s lien law, which allows contractors and suppliers who have gone unpaid on a construction project to file a lien to secure payment. Laws similar to SWEAT have been passed in states including Washington, New Jersey, and Virginia.

The difficulty of collecting owed wages leads many workers not to challenge wage theft, proponents of the bill said.

“Working-class people don’t have a lot of extra time or money to be throwing lawsuits around,” Lister said. “People really don’t want to come together if they don’t have a shot at winning. Without the SWEAT bill, it will be really hard for the workers to get the justice they deserve [even] if they do every single step they are supposed to do.”

When workers do file lawsuits, the difficulty of collecting owed wages often leads them to settle rather than taking their cases to court. A 2015 report on wage collection in New York found that “the majority of cases are resolved for far less than is actually owed due to the fear that a judgment for the full amount owed will never be paid.”

SWEAT has met forceful opposition from the business community. Many New York trade groups representing industries in which wage theft is rampant, such as the Business Council of New York State, the Manufacturers Association of New York, and the New York City Hospitality Alliance, say the bill would have a detrimental effect on small businesses and employment in New York State. Instead, they advocate for judicial review on all lien requests.

Ken Pokalsky, vice president of the Business Council of New York State, told New York Focus the bill would deprive business owners of due process. “It allows this lien on the personal property based on allegations before any actual facts are found,” he said.

He also took issue with the multiple definitions of employer in the bill that would force liens on employers who aren't actually paying the workers and therefore are not responsible for the theft. The bill would extend personal liability to the 10 largest shareholders of non-public companies by making them liable for wages as well as for interest, penalties, damages, attorneys’ fees, and costs incurred by the employee.

“They don’t approve payroll, they don’t withhold payroll, but they happen to be in supervisory positions relative to the employee, and to us that makes absolutely no sense,” Pokalsky said.

Andrew Rigie, Executive Director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, expressed a similar view. “We understand the positive intent of this legislation, but it removes due process for small business owners, mid-level managers and the investors in these businesses, by allowing a lien to be placed on their personal assets based on accusations, not legal findings,” he told New York Focus.

In his veto last year, the governor echoed these arguments, suggesting that the bill would provide “inadequate due process” for employers and that the bill “creates a broad definition of ‘employer’ that includes business entities, owners, and lower-level managers and subordinates.”

The Associated General Contractors of New York State, a leading opponent of SWEAT, has been a contributor to the governor, donating $137,675 to Cuomo campaigns. The governor's office has repeatedly stated over the years that campaign donations do not influence his government actions.

Refuting industry opposition, Sarah Ahn argued that the only party that is being denied due process is the worker.

“What we have been fighting for is that there are no due processes for workers. What we do know is that it’s near impossible to collect on [wage theft] judgments.”

Rosenthal, the primary sponsor of the bill in the Assembly, agrees. “It [SWEAT] doesn’t increase the cost of doing business. The only employers who would be affected by this act are those who have committed wage theft.”

In the meantime, workers like Osmar Figueroa are hoping the law will eventually change in his favor. “I would like to see more support from the government and see laws passed like SWEAT that gives us real rights,” he said.

As for Jin Gou Ke, he has reached out to the Chinese Staff and Workers Center, a workers center in Chinatown, hoping he can launch a lawsuit against his former employer.

“As long as I have the energy, I will fight.”

*This story was published in partnership with New York Focus.*

***

Amir Khafagy is a New York City–based journalist. He has written for publications including The New Republic, Vice, The Appeal, The Guardian, Curbed, The American Prospect, Bloomberg, and In These Times. Follow him on Twitter at @AmirKhafagy91.

Note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Building Contractors Association (BCA) opposes SWEAT. BCA opposed somewhat related legislation specific to the construction industry, but did not take a position on SWEAT.

Max Politics Podcast: Breaking Down the Race for Manhattan District Attorney

(l-r) Top: Tahanie Aboushi, Alvin Bragg, Eliza Orlins, Tali Farhadian Weinstein; Bottom Liz Crotty, Dan Quart, Diana Florence, Lucy Lang

June 9, 2021 - Max Politics Podcast: Breaking Down the Race for Manhattan District Attorney

The Democratic primary for Manhattan District Attorney is one of the most important and competitive races happening this month. Two reporters who have been covering the race -- Jonah Bromwich of The New York Times and Deanna Paul of The Wall Street Journal -- joined the show to give an overview of the eight candidates and key dynamics of the race as voting nears.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think, on Twitter @TweetBenMax. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org.

Read more: Max Politics Podcast: Breaking Down the Race for Manhattan District Attorney

Max Politics Podcast: Why The Manhattan District Attorney Election Is So Important

Manhattan DA Cy Vance (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

June 9, 2021 - Max Politics Podcast: Why The Race For Manhattan District Attorney Is So Important

Host Ben Max was joined by an expert panel for a discussion of the role of Manhattan District Attorney, calls for reforming the way the office functions and the larger criminal justice system, and the ongoing race to replace outgoing DA Cy Vance, which has a key Democratic primary happening this month among eight candidates. The guests include Rebecca Roiphe, a professor at New York Law School and former Manhattan prosecutor; Daniel Alonso, a litigation partner at Buckley LLP, former federal prosecutor, and chief assistant district attorney in Manhattan during Cy Vance’s first term; and Keli Young, the Civil Rights Campaign Coordinator at VOCAL-NY.

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think, via Twitter @TweetBenMax. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to the show live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org.

Read more: Max Politics Podcast: Why The Manhattan District Attorney Election Is So Important

Latino Vote '21 Podcast: Queens, with Assemblymember Jessica González-Rojas

Assemblymember Jessica González-Rojas (photo: @votejgr)

For the third episode of the Latino Vote '21 pop-up podcast, Assemblymember Jessica González-Rojas joined host Eli Valentin to discuss the Latino vote in Queens. Listen through the audio below or find this and other episodes under the "Max & Murphy" podcast stream wherever you get podcasts:

***

Eli Valentin is a political analyst and author of the forthcoming book, Reinhold Niebuhr: A Political Life. On Twitter @EliValentinNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NYCHA’s Latest Rescue Plan Needs State Approval But That Won't Be Coming Anytime Soon

NYCHA Chair Greg Russ (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

*This story was published in partnership with New York Focus.*

With a week left in the legislative session, New York lawmakers shelved a city-backed plan that aimed to revamp 25,000 NYCHA apartments.

On May 21, with just ten working days to go in this year’s session, New York lawmakers added a major item to their docket: a bill that would overhaul how the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) operates tens of thousands of its public housing units, aimed at securing federal funds and private capital to tackle the authority’s $40 billion backlog of repairs.

Then, just weeks later, they shelved it. On Wednesday, State Senator Brian Kavanagh and Assemblymember Steven Cymbrowitz, chairs of the Senate and Assembly Housing Committees, said in a joint statement that they would not be advancing the plan this session.

“We have decided that further conversation, outreach, and negotiation are necessary before advancing legislation on this topic,” Kavanagh and Cymbrowitz said. “For this reason, we will hold the bill in committee for the remainder of the current legislative session…we look forward to continuing to discuss how best to meet the needs of public housing residents in the months ahead.”

The announcement puts in jeopardy NYCHA’s biggest revamp plan in years.

Dubbed the Blueprint for Change, the plan seeks to reform how NYCHA manages repairs and construction, and, crucially, how it funds them. The plan’s main appeal, NYCHA says, is that it would allow the agency to raise more money — up to six times its current federal allocation — to pay for long overdue repairs. It would also put a new entity, the Public Housing Preservation Trust, in charge of those repairs: remediating lead and mold, fixing boilers, elevators, and stoves, and generally bringing apartments up to standard.

In the lead-up to the bill’s introduction, NYCHA sought to convince lawmakers of its urgency.

“Waiting is not an option for us,” NYCHA Chair and CEO Greg Russ told New York Focus in late May. “We’ve spent 25 years waiting on Congress…We have to act now.”

In the wake of the housing chairs’ announcement, a NYCHA spokesperson told New York Focus that the authority would work with legislators to pass the Blueprint in next year’s session. “We remain committed to Blueprint for Change, which we will further refine as we continue to engage with residents and other stakeholders,” the spokesperson said.

Many lawmakers, however, have been wary of Russ’ approach since the beginning, as it relies on transferring NYCHA apartments from Section 9 — traditional public housing — to the voucher program known as Section 8.

“I think, in essence, it would end public housing as we know it,” said Assemblymember Yuh-Line Niou, whose district covers more than a dozen NYCHA developments in the Lower East Side and Chinatown. “It’s a huge risk.”

Her concerns echo those of a vocal group of NYCHA tenant organizers, who see the Blueprint as too close to a scheme that has transferred thousands of units to private management, and fear the plan could further erode a rare bastion of truly affordable rents.

In recent weeks, NYCHA sought to accommodate some of their concerns, negotiating with lawmakers to strengthen tenant protections and significantly reduce the plan’s scope from the initial version introduced last year — scaling it down from 110,000 to 25,000 units.

Nearly half of New York City’s State Senate delegation, including progressives such as Gustavo Rivera and Julia Salazar, co-sponsored the revised bill. Longtime advocacy groups, including the Community Service Society and Legal Aid Society, have also embraced the plan.

As recently as May 25, Kavanagh, lead sponsor of the Blueprint bill, told New York Focus the legislation offered a “promising approach” to redressing NYCHA’s woes but indicated it was a work in progres.

An Alternative to Privatization?

With the legislature’s about-face, the Blueprint joins a string of faltering plans to raise much-needed cash for NYCHA under Mayor Bill de Blasio.

As New York City’s public housing crisis has deepened over the last decade, de Blasio has placed much of the blame for the agency’s decline on long-term federal disinvestment, and turned to the private sector to fill in the gaps. In 2015, de Blasio introduced NextGeneration NYCHA, which included a wide variety of changes including plans to raise money for repairs by building private developments on “underutilized” NYCHA land and shift a few thousand units to private management. In 2018, as the authority faced a federal lawsuit over its failure to clean up lead and mold, came NYCHA 2.0, which aggressively ramped up the NextGen approach, scheduling 62,000 units to be transferred to private management under the federal program known as Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD). Both of these plans, which include different versions of privatization, have faced stiff opposition from tenants.

The Blueprint would not reverse those earlier programs, but seeks to address NYCHA’s more than 100,000 remaining units. It is the brainchild of Russ, who took the agency’s helm in 2019 after leading the public housing authorities in Cambridge, Massachusetts and Minneapolis, where he oversaw thousands of RAD conversions. NYCHA announced the Blueprint in late July 2020, as New York was emerging from the brutal first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

At its core, the plan seeks to do what every other NYCHA plan has sought, and so far failed, to do: raise enough money to close the agency’s enormous repair backlog. NYCHA estimates that this would cost between $18 and $25 billion for all 110,000 non-RAD units, out of a total backlog of around $40 billion and growing.

What’s new about the Blueprint is how it seeks to raise that money: by declaring the tens of thousands of units “obsolete” in order to obtain a special kind of HUD funding, known as Tenant Protection Vouchers (TPVs), then “pooling” the vouchers and issuing bonds against them, effectively taking out loans to finance construction. NYCHA says this would allow it to fund $6 worth of repairs with every dollar it gets from the federal government.

“It’s an ingenious use of an existing HUD program,” said Victor Bach, a senior housing policy analyst at the Community Service Society (CSS).

Bach, who joined CSS in 1983 and leads an annual survey of NYCHA residents, said the Blueprint is the first NYCHA plan in recent memory “that really addresses the full capital deficit that the authority faces.” It would allow NYCHA to upgrade its dilapidated housing stock, he argued, even in the absence of major new federal funding sought by Congressional Democrats as part of President Biden’s infrastructure package.

Bach said he was disappointed that lawmakers had postponed the plan, and that NYCHA should keep the Blueprint up its sleeve given the uncertainties about federal funding.

“So far we haven't heard any other good, alternative ideas, other than Washington coming to the rescue,” he said.

The plan’s opponents, meanwhile, are celebrating.

“I’m glad they have recognized that we will not accept any plan that transfers us out of Section 9,” NYCHA tenant organizer Ramona Ferreyra told New York Focus. She and many other organizers see the Blueprint model as a Faustian bargain that would open NYCHA to backdoor privatization.

“Legally, Section 9 is the only bracket of housing that is public,” Ferreyra said. “According to Congressional statutes and HUD law…in order for housing to be determined public, it has to be within Section 9.”

“So anytime NYCHA says the Blueprint is public, they are lying,” Ferreyra said.

Ferreyra, who lives in NYCHA’s Mitchel Houses in the South Bronx, has spent so much of the last year organizing against the plan that her day job, running the clothing company Ojala Threads, has become “officially a hobby.” She first heard about the Blueprint last summer, when NYCHA “dumped this information” on tenant leaders in the leadup to the plan’s public announcement. She felt it raised more questions than answers, and joined a newly formed group called Residents to Preserve Public Housing, which had just started hosting weekly Zoom meetings to discuss the plan.

As the group’s network extended citywide, its opposition to the Blueprint grew. Its members, who now number about 40 according to Ferreyra, voted not to negotiate with NYCHA over the plan’s terms but to kill it. In December, seated next to her 89-year-old grandmother, Ferreyra was one of a dozen NYCHA residents who spoke at a state legislative hearing about the plan, all of them in opposition.

The Citywide Council of Presidents (CCOP), the elected group representing NYCHA tenant leaders across the five boroughs, is also fighting the Blueprint.

“We are vehemently opposed to it,” said CCOP senior member Reginald H. Bowman, who serves as the group’s legislative liaison as well as president of the Seth Low Houses in Brownsville.

“They’re trying to ram this through, because they have the resources behind them and the support of some of the political establishment,” he told New York Focus in late May. “They’re not listening to the legitimate resident government.”

Some tenant association leaders, meanwhile, lent the plan their support — with caveats.

“We’re living day to day not knowing if we’re going to have hot water, or any water at all,” Claudia Coger, Resident Association President at Astoria Houses, told New York Focus. “We don’t deserve that. We still pay 30 percent of our income on rent.”

“I’m not saying that it’s the best plan, but with the conditions we are sitting in now...we need some immediate action,” said Coger, who has lived in Astoria Houses for 68 years and also serves on the CCOP board, representing Queens.

“What happens if the buildings go into default?”

Advocates like Bach reject the idea that the Blueprint would privatize the units. Rather, he sees it as a “public alternative to RAD,” and says he would prefer to see the units currently in the RAD pipeline go through the Trust model. While he doesn’t support the idea of transferring the units from Section 9 to Section 8 in principle, he thinks that the difference in practice would be “nominal.”

Cea Weaver, campaign coordinator at Housing Justice for All, an advocacy coalition, largely shares this interpretation, if not Bach’s enthusiasm for the plan as a whole.

“I don’t believe that it’s privatization. I do believe that it’s financialization,” Weaver told New York Focus. Taken in context of the authority’s embrace of RAD under de Blasio, “the plan is a clear response to residents’ concerns.”

The revised bill includes a long list of tenant protections to make them “consistent with those afforded to a public housing resident,” according to the text. They include keeping rents at 30 percent of income; ensuring that any tenant required to move out for repairs has a right to return; guaranteeing tenants a right to organize; and maintaining succession rights for family members.

“It’s hugely, hugely improved from some earlier attempts to bring some money into the much-beleaguered agency,” Weaver said. “That being said, there are still some key things about it that are really concerning.”

Above all, Weaver highlights the plan’s reliance on debt and what she describes as inadequate protections in the event that the Trust were to default on a loan.

“The bonds are backed by rents, and the rents don’t cover the costs of operating the building,” she said. “What happens if the buildings go into default?”

Even if the buildings stay solvent, some lawmakers worry that NYCHA could wind up spending a large share of its funding to service debts. Assemblymember Harvey Epstein compares the proposed Preservation Trust to the MTA, which according to the state comptroller has spent 16 cents on every dollar over the past decade servicing its debts — a share that could reach 23 cents by 2023.

“You know who gets a lot of money off people who borrow money? It’s these large private equity companies and large venture capitalists,” said Epstein, who represents fifteen NYCHA developments in Alphabet City and the Lower East Side.

NYCHA chair Russ is confident that the agency has planned its borrowing to match its income.

“We’ve been very careful in estimating our leverage, and also how much money we think we can access if we move to the Tenant Protection Voucher model,” Russ told New York Focus.

The revised Blueprint bill includes provisions that would allow the state or city to intervene if there is a debt issue, and Russ sees little risk that lenders would seek to take over NYCHA property in the event of a default, citing a “tiered set” of legal protections.

“Investors are more likely to want us to give them a financing plan as opposed to taking the property, because they still want to make their return,” Russ said.

For Weaver, such financing plans are precisely where the danger comes in. NYCHA owns a huge amount of valuable land, she said, and even if bondholders aren’t interested in taking over the buildings, the debt could give them inordinate power over how to manage them.

“When a bond goes into default, the bondholder can renegotiate all the terms of everything related to the asset, which is what’s happening in Puerto Rico,” Weaver said. “If bondholders are in a position to take all of those tenant protections that are written into the land lease and just completely renegotiate them… I’d be worried that those protections are not going to last.”

Kavanagh stressed that “there’s nothing about this law that can be changed by a bondholder,” but said he was open to further strengthening the bill text.

One legislator, who asked not to be named, said that the bill’s proponents were considering a revision to ensure that in the event of default, New York City would be responsible for repaying NYCHA’s debt — removing any possibility of private bondholders rewriting terms.

Federal Funds

With the Blueprint shelved, all eyes turn to Congress, where Democrats are seeking a major cash infusion for public housing as part of President Joe Biden’s infrastructure package.

In its original outline, Biden’s American Jobs Plan proposes a $40 billion infusion in capital funding for public housing. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer is proposing to double that sum, with the backing of Nydia Velázquez and other New York Congressmembers. Under Schumer’s proposal, about half of the funds would go to NYCHA.

Progressives, led by Senator Bernie Sanders and Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are aiming still higher with the Green New Deal for Public Housing, which seeks to fully retrofit and decarbonize the country’s decades-old, highly polluting public housing stock. First introduced in 2019, the bill was reintroduced in April with a funding goal of at least $100 billion.

Many residents opposing the Blueprint say NYCHA should have focused on seeking this kind of direct federal funding all along.

“Why is it that public housing leadership is not next to Chuck Schumer saying ‘Thank god, you’ve found a way to deliver the money within Section 9…How can we work on getting this done as quickly as possible?’” Ferreyra asks.

Russ says NYCHA has been “very supportive” of prospects for additional federal capital.

“It’s the first time in maybe forty years that anybody has really talked about funding, and we’re not going be looking away from that at all,” Russ said. “The model we’re proposing works on its own, and it also either complements or supplements anything we could get from the federal government.”

Among the revisions to this year’s Blueprint bill was language requiring the Trust to “adopt rules or regulations establishing sustainable design guidelines,” including criteria for converting appliances to electric and generating renewable energy, which Russ said made it compatible with a Green New Deal.

NYCHA emphasizes that the renovations would create hundreds of long-term green jobs, along with thousands of shorter-term construction jobs, and that the Trust would be mandated to hire NYCHA residents whenever possible, consistent with federal regulations.

“So Many Promises”

If these promises failed to win over many tenants and lawmakers, it boils down to one fundamental reason: trust.

“At this point, they’ve heard so many promises that were made, most people just don’t believe one way or the other in what is being said,” Assemblymember Latrice Walker told New York Focus. Walker represents Brooklyn’s Brownsville and Ocean Hill neighborhoods, home to a higher concentration of NYCHA residents than almost any other legislative district, and has experienced firsthand the effects of an earlier effort to convert public housing to Section 8.

Walker was a teenager in the late 1990s when NYCHA announced its first-ever demolition plan, targeting Brownsville’s Prospect Plaza Houses, where she lived. The development’s 12- and 15-story buildings were to be torn down and replaced with rowhouses under the Clinton-era HOPE VI program. NYCHA moved tenants out in 2000, with $21 million in HUD funding to begin the demolition.

More than a decade later, the hollowed-out buildings were still standing, while more than 1,000 residents were scattered across the city and beyond. It wasn’t until 2017 that new buildings were completed in their place — with just 80 apartments still in NYCHA’s hands.

“Ultimately I was displaced because of it,” said Walker. “A lot of folks, even though they had a right to return, the right to return was never realized.”

The saga inspired Walker to enter politics, with the goal of defending the rights of tenants like her family and neighbors. Prospect Plaza has remained an exception in NYCHA’s history, as New York, unlike many other cities, has left virtually all of its public housing standing. But it left its scars, and as NYCHA has cycled through a series of private-sector-oriented reform schemes to allay its chronic lack of funding, trust has continued to erode.

“So when I heard about the Blueprint, my spidey senses became awoken,” Walker told New York Focus. She was pleased with some of the changes introduced in the revised bill, but still “not totally sold on the initiative.”

“Until my community is on board with it, then it’s definitely not something that I can support,” she said. “They have to do a lot more groundwork, a lot more outreach to the residents to get buy-in.”

Barbara Brancaccio, NYCHA’s communications director, says the agency has already done extensive outreach for the plan.

“We’ve literally touched every household on multiple occasions through endless mailings,” as well as posters, social media, and email blasts, she said. The authority has also hired a consulting firm, NYC Action Lab, to canvas for the plan, at a cost of $250,000.

For Bowman, of CCOP, such outreach is no substitute for long-term collaboration with residents.

“That’s a campaign, that’s not consensus,” he said. “That’s like telling me, ‘Well, I ran $1 million worth of commercials on selling a product, but nobody bought the product.’”

“When The Dust Settles”

Many lawmakers said that with such fierce tenant opposition and so few days left in the legislative calendar, it wasn’t the moment to push the plan through.

“Everyone is in agreement with the fact that to keep doing the same thing and expecting a different outcome is insanity,” Walker said. But she wanted to see more dialogue before moving ahead.

Epstein, too, felt there had been insufficient resident input and that it would be inappropriate to “rush” the plan through the legislature.

“I guess neither Washington nor the legislature may have the same sense of urgency that we do,” lamented Bach, of CSS. Nevertheless, he hopes that Congressional Democrats will find a way to deliver the $80 billion they’ve promised. If so, “then there may be no need for a Preservation Trust, or it could be a modified program.”

“But if Washington comes short of that, then NYCHA will still have to go the route of conversion through the Trust or through RAD to meet its capital needs,” he continued. “So a lot depends on what happens when the dust settles in Washington.”

Perhaps just as decisive will be this month’s mayoral primary, which both Bach and Weaver worry could tip the scales back towards privatization.

“The outcome could put NYCHA and its residents even more at risk,” Bach said. “Having the Preservation Trust in hand would have made it possible for the Authority to address its entire capital needs regardless of who is elected.”

“I’m scared of the next mayor pursuing RAD at a much more aggressive pace,” Weaver said. The Trust model “is just so much better than that.”

Still, a spirited group of residents is as committed as ever to defeating the plan once and for all — and, in Ferreyra’s words, “end[ing] the political career of anyone supporting the Blueprint.” Residents to Preserve Public Housing is planning a “Day of Rage” against the Blueprint on June 10, and members are circulating a petition to remove Russ as NYCHA chair.

“He came in with this plan, and he thought we weren’t going to notice,” Ferreyra said of Russ. “I don’t think he was expecting this pushback.”

*This story was published in partnership with New York Focus.*

***

by Colin Kinniburgh for New York Focus

@nysfocus

@GothamGazette

As Latest Reforms Head to Voters for Approval, Advocates Celebrate Passage of Extensive Election Package

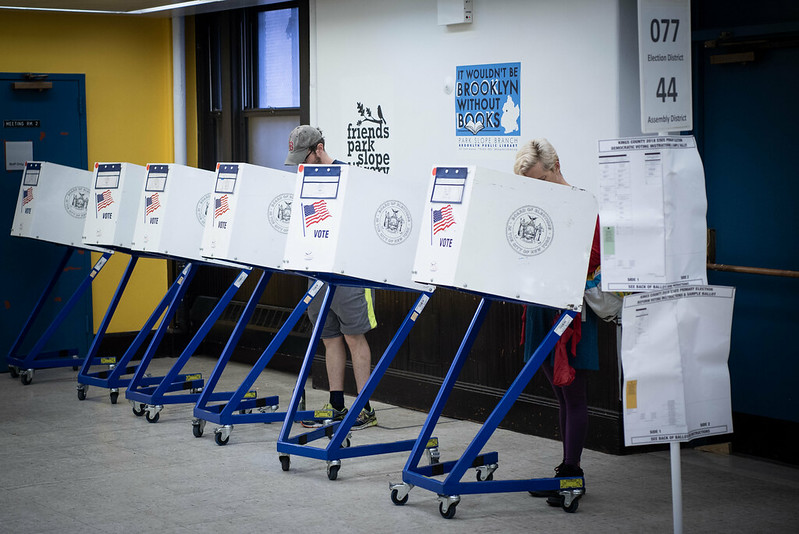

Voting (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

The New York State Assembly on Tuesday approved two bills that would amend the state constitution to make significant changes to voting laws, and the proposals will now go to voters on this fall’s ballot.

One would allow voters to request “no excuse” absentee ballots, opening up voting by mail to all. The other would allow voters to register to vote and cast a ballot on the same day. The bills had been previously approved by the Senate, and passed by both houses of the State Legislature in the last session, and will now head to voters across the state for their approval or disapproval as questions on the 2021 general election ballot.

The two bills marked the successful passage of the last remaining items on an agenda first put forward by the Let NY Vote coalition in 2017. The coalition, made up of more than 175 organizations from across the state, had already succeeded in advocating for the legislative passage of early voting, more flexibility in changing political party affiliation, pre-registering 16- and 17-year olds to vote, consolidating primary dates, automatic voter registration, and for the restoration of voting rights to formerly incarcerated New Yorkers.

The passage of most of these many significant changes to New York voting and elections was made possible by the fact that Democrats took control of the State Senate, and thus both houses of the Legislature and governor’s office, through the 2018 elections and have made these reforms, many of them opposed by Republicans, among their top priorities.

“The Assembly Majority is committed to making it easier for voters to exercise their constitutional right to vote,” Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, a Bronx Democrat, said in a statement on Tuesday. “These bills will increase accessibility to the polls and continue some of the safety precautions we began taking during the pandemic. As we see states roll back access to voting, New York will fight to make sure every eligible voter is able to have their voice heard.”

“Voting is an integral part of ensuring a functioning democracy, and part of our civic duty as Americans,” said Assemblymember Latrice Walker, a Brooklyn Democrat who chairs the election law committee, in a statement. “The Assembly Majority will continue working to ensure every eligible voter has access to the ballot – whether in person or by absentee ballot – and is able to have their voice heard.”

Activists from the non-partisan Let NY Vote coalition celebrated the passage of the bills. “Our work is not done, but right now, it is a little bit easier to vote in New York," said Sarah Goff, deputy director of Common Cause New York, in part, in a statement. Amanda Blair and Amanda Richie, co-founders of Brooklyn Voters Alliance, said in a statement that New York is “one step closer to becoming a beacon for democracy." Murad Awadeh, executive director of the New York Immigration Coalition, noted, “Newly naturalized voters, in particular, can finally navigate what was once an outdated and opaque voter registration process.”

Despite its reputation as something of a progressive state, New York had, until recent years, among the nation’s most archaic election and voting laws. In the 2016 presidential election, the state ranked 41 out of 50 states for voter turnout. Voting rights activists had long pointed out that though New York did not undertake any overt attempts to discourage voter participation like some Republican-led states, its laws effectively led to passive voter suppression. Roadblocks included the split Legislature as well as the fact that many entrenched Democratic incumbents have been more than happy to leave the suppressive system in place.

After years of languishing before the Legislature, election and voting reforms were quickly ushered through when the Democrats grabbed control of the state Senate amid a “blue wave” in 2018. At the forefront of the reforms were newly elected progressive Democrats in the state Senate, who had replaced more moderate members of their party who had caucused with Republicans under the banner of the breakaway Independent Democratic Conference.

For instance, the state had the earliest deadline in the country for switching party affiliation to vote in an election – it was roughly six months prior to primary election day before it was shortened in 2019 to just about ten weeks. Early voting had been in place in 37 other states before New York approved it earlier that same year, while also consolidating state and congressional primaries that had been held on separate dates, discouraging turnout. Sixteen other states and Washington D.C. had already approved automatic voter registration before New York passed it into law in December 2020. And just last week, Governor Andrew Cuomo signed into law a bill that restored voting rights to people released from prison.

There are still voting and election reforms some would like to see out of Albany, including reforms to how state and local boards of elections are structured and operate.

The coronavirus pandemic lent added urgency to expand access to voting. Through executive and legislative action, voters saw expanded early voting hours and easier access to absentee ballots. If the ballot referenda should pass in November, New York will join 38 other states that now allow no-excuse absentee voting, and 18 states and D.C. that already have same-day registration.