John Liu Defiant After City Board Denies Funds For His Mayoral Campaign

NEW YORK — Even after losing out on millions in public funding for his mayoral campaign, Democratic candidate John Liu is refusing to back out of the race for City Hall.

"For the last couple of years, I've taken body blow after body blow after body blow. But there’s not going to be a knock down here,” Liu said yesterday following the decision by the city’s Campaign Finance Board to deny his campaign matching public funds.

But he admitted that yesterday's decision by the city’s Campaign Finance Board to deny his campaign matching public funds, after citing irregularities, would take a toll.

"There's no question that this weakens my campaign," he said, as 60 or so supporters stood with him in front of the Municipal Building across from City Hall.

The decision by the board was not entirely surprising given that two of the candidate’s campaign aides were convicted in an illegal fundraising scheme earlier this year. Those convictions failed to dispel questions about the collection of donations by Liu’s campaign. Liu has not been charged or accused in the cases.

Without the public funds and barring any money he can raise between now and the Sept. 10 primary, records indicated Liu had little more than $1.5 million left to spend — leaving him at a considerable financial disadvantage in the jam-packed race for the Democratic nomination.

Liu, who is the city’s comptroller, said that his campaign would strongly consider appealing the board's verdict, but couldn't count on it being successful. Liu and his campaign attorney, Martin Connor, said that even with a successful appeal, it would only give them five or six days to spend the more than $3 million he would have received if not for the board's decision.

"We've got five weeks to work really hard," Liu said. "And though we may not have the millions of dollars that the Campaign Finance Board has chosen to withhold from our campaign and from our donors, the strength of this campaign has never been in the money. The strength of this campaign has always been in the people."

Liu, who stood alongside leaders from CWA Local 1180, DC 37 and the Correction Officers' Benevolent Association, was often drowned out by his supporters, who alternated chants of "Mayor Liu" and "Tell us why."

Despite trailing in many of the polls of Democratic mayoral candidates, those alongside Liu were just as eager to answer reporters questions to Liu.

Without any cue or hesitation, Corrections Officers Benevolent Association President Norman Seabrook spoke up for Liu while resting his hand on candidate's shoulder.

Seabrook tried to make the case that the board's political appointments — especially the two made by and Liu mayoral rival and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn — should have recused themselves from the vote.

When a reporter asked Seabrook who he was, the union leader pointed to the cheering and chanting crowd.

"John Liu," he responded. "We're all John Liu today."

Seabrook pressed for responses from Liu’s other rivals too. Only one has publicly acknowledged the hearing: Former Comptroller Bill Thompson told Capital New York that Liu’s candidacy was a question better suited for the voter than for the board.

"You hate to see something happen that way, and you really would much prefer to see the voters decide," Thompson told Capital New York.

But even if the two board members had recused themselves, the vote to deny Liu's matching funds was unanimous. Board Executive Director Amy Loprest told reporters that the decision was based both on the federal cases against the former Liu campaign as well as an independent investigation paid for by the CFB.

That investigation, the board said, uncovered a pattern of behavior similar to the federal cases.

The board's chair, the Rev. Joseph Parkes, said the potential violations were "serious and pervasive," and put the blame squarely on Liu.

"The candidate is ultimately responsible for the campaign’s compliance with the law," said Parkes' statement, citing the 1988 Campaign Finance Act. "The choice to withhold payment does not require a finding that the candidate has personally engaged in misconduct, however. Under the act and board rules, the actions of a campaign’s treasurer or other agents are legally indistinguishable from the campaign."

To that end, board members argued, their conclusion isn’t a slight to the donors whose funds would not be matched. The responsibility to donors to follow the law, Loprest said, isn’t on the board but rather on the campaign.

During yesterday’s public meeting, Connor admitted that the Liu campaign had suffered it’s shares of setbacks, but that the greater number of Liu's 6,259 individual contributions should still be eligible for matching funds.

"It’s no secret that there were problems in the Liu campaign in 2011," he said. "There’s an old saying about where there’s smoke. Sometimes, where there’s smoke, there’s smoke and no fire."

Connor also argued at the meeting that the board had violated its own rules by only giving Liu eight days to respond to complaints about invalid matching claims. Comparatively, Connor said, other campaigns had 32 months to correct information on what he argued were technical mistakes.

He also argued that the independent, 139-page report conducted by Thacher Associates, LLC., incorrectly interpreted finance law and discriminated against donors based on presumed income levels.

The board did not respond to inquiries about the report's timeline.

Regardless of the report's criteria, however, Connor argued that the board's penalization of the campaign and donors because of two individual's misdeeds could be the Liu campaign's final blow.

"A complete denial of matching fund is the equivalence of imposing the death penalty for pickpocketing," Connor wrote in response to the Thacher report last week. He again invoked the death penalty metaphor at the hearing.

Some Liu supporters said they would work to raise more funds outside the public matching system.

Peter Killen, 75, was one of at least seven Staten Island residents and Liu supporters at the public meeting. Having donated $300 to the Liu campaign since late 2012, Killen — a retired police officer — said he was still committed to seeing Liu win the race.

"It was a kangaroo court," he said of the board, adding that he was surprised and disheartened by the ruling. "I'm going to try to get 5,000 more people to donate the maximum to make up for this travesty of justice."

Liu himself seemed equally resigned to the verdict, telling reporters that he wouldn’t “cry over spilled milk.”

"If any other campaign had been put up to this level of scrutiny by the Campaign Finance Board or by anybody else, I have no doubt that we would be head and shoulders above the rest in the amount of documentation," he said. "There's no question that there are some pretty powerful forces in this city who do not want me to be mayor."

Mayoral candidate John Liu (Thacher Report Final FOIL Distribution) by Gotham Gazette

GothamVotes: A Conversation With Mayoral Candidate Christine Quinn

NEW YORK — Christine Quinn could make history as the first woman and openly gay mayor of New York City.

The self-described aggressive City Council speaker has long been a front-runner to replace Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Even so, she will need to overcome powerful headwinds to get Democratic voters to turn out for her in the September primary.

Quinn became speaker of the New York City Council in 2006; her first strike of the gavel in Council chambers came at the cusp of Bloomberg's second term. Despite a long legislative record after 14 year on the Council, Quinn's reputation has been dogged by her largely unpopular decision to support Bloomberg's push to change the law so that he could run for a third term.

Since then, her stewardship of the legislative branch has been marked by her willingness to work with the mayor. As a result, her loudest critics say her cooperation with the current administration would make hers a de facto fourth term for Bloomberg.

That's not to say that Quinn has not stepped outside of Bloomberg's shadow on occasion, even leading on issues that rankle the Bloomberg administration. Especially over the past year, she's been at the helm as the Council asserted a degree of independence by overriding mayoral vetoes of the living wage, paid sick leave and vendor fine bills. The Council is positioned to do the same over Bloomberg's opposition to the police inspector general bill.

Quinn talked about that bill, her relationship to the mayor, how she’d work with her successor and more in an exclusive interview with the Gotham Gazette.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Let's start with one of the big things that the Council did last year: open data.

CHRISTINE QUINN: Yes, we love open data. And I love that the Council was a big part of that, though I want to give (Councilwoman) Gale Brewer credit where credit is due because she certainly was a driving force behind that. But, you know, it's interesting that something like open data can seem like it's wonky, silly or just numbers, but when we had the situation with the ambulance — we now have really good data on response rate. That's not the kind of thing they always had.

That matters, because knowing if what happened in Williamsburg was an outlier — doesn't make it okay — but it's a different situation if it's an outlier versus what was happening everywhere. So open data is really important in helping us figure out what needs to be responded to, how it needs to be responded to, but also hopefully more efficiently involving workers, advocates and others in the process of developing solutions to problems.

GG: Obviously we're still technically in the early days of the law, but so far the city agencies subject to it haven't met their first deadlines.

CQ: Not in total, but I think — I don't know if others would disagree — I don't think we see a lot of lawless response. I don't think we see agencies flipping the bird off to open data. I think we see more of it being a little more complicated, which underscores the need of it.

GG: On the topic of transparency, one of the chief complaints lobbed at your record is transparency in terms of budgets and member items.

CQ: Oh my God, are you crazy — it's the total opposite. No. You're going to want to rewrite the whole question. My office, my office and the entire City Council under my leadership has brought more transparency to the budget process than ever before. If folks want to say more is needed, I'm open to that constructive criticism.

But, look: when I got elected speaker, you had a long, chunky Schedule C. It was largely impossible to figure out what Council members got what amount of money, what groups got what amount of money. You can now go to a database and get all of that information with a few strokes of a key. Grants given from the speaker's office never before had names associated with them. That's all changed.

One of the areas I've struggled with — and maybe data folks can help the next speaker on this — I'd love there to be more information on what the grant is funding. Because these two or three sentence descriptions are accurate but they're not particularly illuminating. I would also love — and this is challenging — but let's say a group is supposed to run after school programs and take care of 30 children a month. I'd love to be able to put online who met their goals, who didn't meet their goals. Who exceeded their goals. I'd like to be able to merge Council data with agency data so you know who got unsatisfactory, you know who got unsatisfactory. And that getting unsatisfactory puts those groups' funding in jeopardy.

GG: But people are starting to throw the words "slush fund" around and pointing to members items being allocated towards former Assemblyman Vito Lopez's nonprofit, or the investigation into Councilman Dan Halloran.

CQ: Well, look, there is a totally different, night-and-day difference from the system I inherited. I inherited an honor system where the assumption was that any group that a Council member requested to fund was a quality group. I found out fairly quickly that was a broken system. I asked for help from law enforcement, the Department of Investigation, and we've changed that system completely.

And what Dan Halloran was allegedly trying to do would not have been doable. So I took the problems we had very seriously. And we've completely changed the system with the Council's verification process, the Mayor's Office of Contracts verification process and a lengthy list of additional rules. It's important because we know there are bad people who are trying to steal money in the budget, and it's outrageous that anyone is trying to misuse that money.

But when you're an elected official you're going to have problems come across your desk. I believe you're judged by if you admit the problem, do you ask for help? Do you fix it and come up with a solution? Those are the things I did and I'm extremely proud of it.

GG: The budget dance — you've said before it's not something that you engage in, that it's something you're forced into.

CQ: It's going to end when I'm mayor. Because I'm going to put out budget that are a reflection of my priorities and a reflection of the actual state of the finances of the city. There have been many years that I've been speaker working with Mike Bloomberg where he had no choice but to propose cutting the budget because we were in deficit. But there were other years where Mayor Bloomberg proposed to cut everything out of the budget that the Council put in. That's not based on the economic reality, because those cuts weren't necessary.

A budget is the most significant statement of your priorities, and we need a budget put out by a mayor that reflects those priorities.

GG: To that end, how would you deal with some of the larger ticket, long-term times like pension and healthcare costs?

CQ: Those are going to be some of the things that are squarely on the table with the union negotiations. They need to be addressed between the mayor and the unions, but that doesn't mean that the larger expenses by city agencies, the larger capital parts of the budget shouldn't be looked at more globally in the budget process.

GG: You've had a couple of dances yourself with the mayor. What qualities do you want in whoever succeeds you as speaker?

CQ: I want for the next speaker to be someone who really believes in and respects the institution. I hope the next speaker shares my belief that you get more done working with the mayor than being constantly in disagreement with the mayor just for the sake of disagreement. But I know whoever the next speaker will be, they'll be someone who when we can't agree, we'll disagree agreeably.

We had days when all the Council did was disagree with the mayor just to get in the papers. I hope we don't go back to that, but I also recognize we're not always going to agree.

GG: One of the issues that you've agreed with the mayor on is your opposition to the expansion of the racial profiling ban. As mayor, is it something that you'd try to fight?

CQ: Obviously as mayor, I'd have to respect the laws that get legally established, even if you disagree with them. I'm very excited, actually, about the inspector general and potential it has to get more good information about how to run the police department better.

GG: The debate over the Upper East Side waste transfer station has really become one of the standout issues in the race.

CQ: Yep.

GG: You've said before that you wouldn't want something in another neighborhood that you wouldn't have in your own district. There's a difference, though between what's going on in the Upper East Side and at the Gansevoort station: the Upper East site would be a waste transfer whereas the other is a recycling station.

CQ: Yes, but in essence it is the same thing. There will be a facility that garbage trucks will come in and out of and tip garbage-related elements onto barges. In the Upper East Side it will be garbage; in the West Village, it'll be recycling. But the issues is the same: a facility, trucks, using the river in a park. They're probably two of the facilities in the entire plan that are the most similar because of their relationship to park spaces — different kinds of park spaces.

GG: If that's the case, though, would you entertain the idea of switching the two stations?

CQ: The plan needs to move forward. The plan needs to move forward as is. And that's what I'm going to do. There's not value in changing the plan. This plan took decades to implement, and people who don't want something in their neighborhoods, throwing in red herrings and lawsuits, switch this for that, or go put another facility on the west side of Manhattan — that would cost another $300 million give or take. They're just throwing out red herrings because they don't want to do their fair share. Period. End of conversation.

This plan is going to be implemented when I'm mayor.

GG: On public transportation, you've come out in support of expanding almost every form of mass transit: buses, bikes, ferries. And you've come out in support of taking mayoral control over the MTA. How exactly can the city under a Quinn administration handle that kind of responsibility?

CQ: Right now, we're taking more than our fair share of the burden because we don't have the right share of our voice on the board. We are the economic engine of the MTA, paying for more than our fair share and we have the voice of a piston. Those days need to end.

Bus rapid transit, select bus service — it doesn't cost anywhere near what it costs to build a subway. Ferries do take a subsidy — there's no way around that. And mass transit takes subsidies. But the effectiveness of those subsidies are done right in a multimodal, inter- and intra-borough way, we're seeing how effective it is. And as usage grows, the subsidies will obviously decrease.

GG: One of the big collaborative projects that's already happening between the state and the city is Sandy reconstruction. What's your take on waterfront development given that the state isn't a fan but Mayor Bloomberg is?

CQ: We're a city of islands. So we need to develop responsibly in a post-climate change environment. But we can't retreat from our waterfront. Now that doesn't mean you develop everywhere and every way. There are neighborhoods in Staten Island that want to be bought out, and we have an obligation to respect that. But we also have an obligation to respect the voices in Breezy Point and other places that say "we want to rebuild."

It's about not doing it where it's irresponsible, and where you do do it, doing it with requirements, materials and standards that make it as safe as possible.

GG: Along the same lines of development, one of Mayor Bloomberg's legacies really is going to be zoning policy. So what's your vision on zoning post-Bloomberg?

CQ: I think that's very true. One of the things that the mayor is known for is big rezoning projects. In some places, those have had great positives. In others, folks would argue some of the promise was not fulfilled. I'm probably going to start with a more neighborhood-based focus.

I really want to seize the potential of our neighborhoods to build 40,000 new middle-income housing units. I want us to seize the potential of our neighborhoods through my Keeping Opportunity Close to Home plan — KOCH, in case you didn't get that — to incentivize neighborhood economic development.

So I think you're going to see a bit more of a neighborhood opp versus big zoning down vision.

GG: Finally, as speaker, your Council's had a significant record on immigration, whether it be dealing with the city's deportation policy or naturalization programs. How would your immigration policy carry over if you're elected mayor?

CQ: Well, this is an immigrant town. My grandparents came here from Ireland 100 years ago, give or take — all four of them. If you had met them, they literally talked about this city as magical, that it had mythical powers. You gotta put yourself back in time — they left Ireland with no belief they would ever go home. But this was not just America — it was New York, a place you went to where you have the potential to be free and get out of poverty.

And that happened for all four of them. And I want to keep New York that place so that other Quinns and Callaghans and Lancers and Shines of the 21st Century and come here and have that same potential. One of my grandparents had an eighth grade education, most had second or third. But all of their children went to college. Now, it's different than it was then, but I want to keep that potential.

Superstorm Sandy Shapes Southern Brooklyn City Council Race

NEW YORK — Like many seaside communities in southern Brooklyn, the neighborhoods of the 48th City Council District were in the path of Superstorm Sandy when it struck nine months ago.

Manhattan Beach was engulfed in waves from the Atlantic Ocean in the south and from Sheepshead Bay in the north. Along Neptune Avenue, which runs through Brighton Beach, the floodwaters rose in some parts to about 10 feet when the hurricane reached its peak.

Nine months later, residents and local leaders are asking what will happen the next time a major storm sweeps through their communities.

That discussion is helping to shape the fiercely contested City Council race for the 48th district, which includes parts of Brighton Beach, Midwood, Sheepshead Bay and Gerritsen Beach, and is home to strong Russian, Arabic and Orthodox Jewish enclaves.

Six contenders are vying to replace term-limited Councilman Michael Nelson: Community Board 15 Chairwoman Theresa Scavo; Nelson aide Chaim Deutsch; district leader and journalist Ari Kagan; attorney Igor Oberman; attorney Natraj Bhushan; and former state Sen. David Storobin. The primary is Sept. 10.

While the five Democratic candidates interviewed for this story say they don’t have exact plans for preparing for future extreme weather, all agree that it is a priority. Storobin, the lone Republican, didn’t respond to requests for interviews.

Scavo said that if she gets elected to the Council her first piece of legislation would call for giving property tax credits to homeowners if they install backwater valves to prevent flooding from the sewer system. She said the valves could cost between $1,500 and $2,000 each.

“A lot of the problems that occurred here was sewer back up because the sewers are so small they couldn’t handle the heavy downpour of rain plus water from the bay and the ocean,” said Scavo, 61, who besides her work for community board 15 volunteers her time to numerous local organizations. She has been endorsed by the Southern Brooklyn Democrats.

Igor Oberman, the board president of the Trump Village West co-op in Brighton Beach and one of three Russian-born candidates in the race, said he had seen proposals for safeguarding the beaches but wasn’t ready to pass judgment on them.

“I have to say I have been trying [to] wrap my head around them,” said the 40-year-old candidate, who records show made a $250 donation to Storobin’s 2012 state Senate campaign but as a Democratic has earned the support of progressive groups including the Working Families Party and 32BJ SEIU. “Several months have gone by where they have talked about should we do it like New Orleans [did] it with levees. I’m not sure … But we need to start having a much more serious discussion.”

Fellow Russian-born candidate Kagan, who is expected to get the support of influential local Russian American media mogul Gregory Davidzon, suggested opening beachside kiosks where the profits would go toward improving infrastructure in the district. Each neighborhood would have its own store, he suggested, that would sell items like sunscreen, goggles and water, and rent equipment like umbrellas, chairs and surf boards.

“Sandy affected our district big time, especially the south part of the district. We are still recovering. We have very old outdated sewer system and surge systems,” said Kagan, 46, who has been endorsed by a handful of liberal organizations, including the United Federation of Teachers.

Kagan and Storobin are seen as archenemies in the race, each fighting to sway the Orthodox Jewish vote.

For Bhushan, the youngest of the candidates at 27, Sandy was his main reason for jumping into the race. He said he was particularly concerned about how money for storm recovery would be distributed. “Do I have a particular plan in place? No, I don’t, but a particular plan is something I would like to craft,” said the long-shot candidate who has little in the way of financial or political backing from the establishment.

A citywide report on the effects of Sandy released by Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration in June detailed how most of southern Brooklyn was prone to flooding because of the area’s bays, creeks and inlets. Homes and buildings in Manhattan Beach and Sea Gate were battered because there was no coastal protection. The beaches lost 272,000 cubic yards of sand.

As part of its plan for building a more resilient city, the Bloomberg administration has proposed replacing about one million cubic yards of sand around the coastal areas and raising barriers in low-lying areas at risk of flooding.

Deutsch, who has worked for the City Council for 17 years and is founder of the Flatbush Shomrin — a neighborhood watchdog group made up of local Jewish residents who are unarmed and serve as “eyes and ears” for the police department — said he wants to make sure any proposals are safe for residents and that there is sufficient funding for the plans.

“There are a lot of answers we still have to look forward to, and how it is going to be paid for,” said Deutsch, 44, who has been endorsed by Nelson. “We have to plan, and not just a plan that is good on paper but a plan that makes sense.”

He said more talks are necessary before he can back any plans.

Scavo said she plans to use the power of her voice to make sure investments in the district help the district to prepare for future extreme weather.

“You get out there in the street and rally the truth,” she said. “Your mouth will get funding here. We need someone to lead the people to ask for help, and right now it’s very quiet.”

Of the candidates, Oberman is leading in fundraising with over $100,000. Scavo is the only candidate who comes close with over $95,000 in her war chest. Deutsch has $77,000, and Kagan has almost $76,000. Storobin, who was endorsed by Republican mayoral frontrunner Joe Lhota, filed his first round of fundraising with $45,000. Bhushan, who has said he is not focused on fundraising, trails with almost $4,000.

All of the candidates, except Bhushan, have received campaign contributions from developers, attorneys and construction companies — not surprising, given the number of homeowners in the district.

The candidates will receive six-to-one matched donations through the public campaign finance system. The next filing deadline is Aug. 9.

48th City Council District Candidates

Natraj Bhushan, a longtime resident of the district and an attorney, graduated from City University of New York School of Law at Queens College. He was born in Oklahoma and moved to New York when he was 6. He interned at Councilman Leroy Comrie's office in 2008, and gave free legal services to Nelson's office during Superstorm Sandy.

Chaim Deutsch, who has lived in Brooklyn all his life, organized a group of Jewish volunteers as the Flatbush Shromin neighborhood watchdog group in 1991. He is currently aide to term-limited 48th district City Councilman Mike Nelson and has worked for the Council for 17 years.

Ari Kagan was born in Russian and moved to the United States over 20 years ago. Since moving to Brooklyn, Kagan has worked as a journalist for a Russian newspaper and hosts a Russian TV show. He was an aide to city comptroller and mayoral hopeful John Liu as well as Congressman Michael McMahon. He graduated from Baruch College.

Igor Oberman fled with his family to the United States in 1981 from the former Soviet Union to avoid religious oppression. He was 8-years-old. Since moving to Brooklyn he became the first of his family to graduate college and went on to obtain a law degree. He has served as a judge at the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings and worked for Borough President Marty Markowitz as a liaison to Russian and Jewish communities. He is also the board president of the board of directors of Trump Village West co-op in Brighton Beach. He graduated cum laude from Brooklyn College and attended New York Law School.

Theresa Scavo, a former public schools teacher, has been a member of Community Board 15 for 13 years and has been chair since 2006. She is also the vice president of the High Way Democratic Club. She owned a retail business for 26 years. A life-long resident of Brooklyn, Scavo graduated from Hunter College and went to Richmond College for her master's degree.

David Storobin is a Russian native who is a real estate broker and an attorney. He ran for state Senator and won only to serve for 11 days because his district was eliminated after the district lines were redrawn. He is vice-chairman of the Kings County Republican Party. He received his law degree from Rutgers University.

GothamVotes: Thompson On Stop-And-Frisk, Racial Profiling And The Next Comptroller

NEW YORK — Bill Thompson nearly stole Michael Bloomberg's third-term dreams away in 2009. This time around, he’s the only black candidate in the race. Unencumbered by any major political scandal or unpopular policy decision, such as extending term limits, he would seem to have frontrunner status all but pinned down.

And yet Thompson has struggled to stand out among this year’s Democratic candidates, often polling in the middle of the pack. That may have begun to change in recent weeks.

Following criticism from some that he had taken a too moderate stance on the New York Police Department's stop-and-frisk tactics, Thompson has become more outspoken on issues of race and policing. The day after a Florida jury acquitted 17-year-old Trayvon Martin’s shooter, George Zimmerman, Thompson’s campaign tweeted, “Trayvon Martin was killed because he was black. There was no justice done today in Florida.”

Yesterday, he delivered a speech on race, again invoking Martin’s death and linking it to issues close to home.

“Here in New York City, we have institutionalized Mr. Zimmerman’s suspicion with a policy that all but requires our police officers to treat young black and Latino men with suspicion, to stop them and frisk them because of the color of their skin,” Thompson said.

We interviewed Thompson exclusively on a recent Friday before he was set to spend the night at public housing in East Harlem with a handful of other Democratic mayoral hopefuls in an event sponsored by the Rev. Al Sharpton's National Action Network. He spoke at length about his position on stop-and-frisk, racial profiling, educational policy including mayoral control, sustainability and how he expects to work with the city's next comptroller (even if his name just happens to be Eliot Spitzer).

GOTHAM GAZETTE: Before we started this interview, we were talking about the various problems plaguing the city's Public Housing Authority, from the failure to install security cameras at developments to making much-needed repairs. Do you want to finish your thoughts?

BILL THOMPSON: The thing that has made it even more outrageous is the fact that they have money — and clearly not the money that's necessary to bring things to the level that it should be — but they sat on a billion dollars. And those are dollars that could have been used for renovation, dollars that could have been used for the upkeep and maintenance, dollars that could have been used to fix elevators, dollars that could have been used to get rid of mold and to fix leaking plumbing and other things.

GG: What do you think of the Bloomberg administration's plan to take care of the backlog of repairs?

BT: The thing about it is that you continue to be told that things are gonna be improved ... If it hasn't been done up to now, why would it be done? At least to the level that it needs to be. I mean, looking at the security cameras where you had $42 million. That wasn't installed. There was a commitment made on that. And it's clear that — I think, if I remember correctly, of dozens of developments that are supposed to have security cameras installed, they have only done eleven. I need to go back and look. I don't remember the exact number. But that's not on target. All of that together, you know, why would we believe that it should get done by now?

GG: What would you do differently than the Bloomberg administration?

BT: I think it's looking at not just the backlog but also what do you do better moving forward? At this point, how are repairs done? I mean, most have been done at a central location. Clearly that hasn't been working. Not being there right now and not exactly knowing how they are going about it, it's clear you have to change that, it's clear you have to start to create more of a list of priorities.

And, another thing, they have been sitting on money. And I think that's the thing that angers people even more. While there's necessary repairs that need to be made, they sat on money. And not just a little. You know, a billion dollars. And just a number of things that have occurred in the Housing Authority that are just incredibly unfair.

When you look at the money that comes off the top every year — take $75 million off the top for police protection — I don't see that happening any other place. People in the Housing Authority pay taxes also. Why this kind of double billing? I would eliminate that. I am not going to take money off the top.

GG: In some articles on your position on stop-and-frisk, you have said there has been an "overreaction" to the policy. Can you explain further your position on police stops?

BT: Here's what I meant. What I've said all along is that stop-and-frisk has been misused and abused by this administration. That when people are being stopped only because of who they are and what they look like, there's something wrong.

If I'm the mayor of the city of New York, people aren't going to be profiled. We aren't going to have stop-and-frisk continue to be misused. My police commissioner isn't going to misuse it the way it's been done. It's not going to be tied to performance goals. It will become a policing tool. That's exactly what it is. You don't want to eliminate it.

GG: What do you think about the Community Safety Act, which includes a bill to strengthen anti-racial profiling by police?

BT: Profiling is illegal. It isn't supposed to occur. Rather than just having legislation that perhaps adds additional bureaucracy, why don't we just have a mayor that won't engage in these practices? That won't allow people to be profiled? That will make sure that doesn't occur? That's the kind of mayor I want to be. I don't need the additional bureaucracy or the additional problems. I understand the legislation is moving forward. Everybody is frustrated. Everybody is tired of what's occurred.

The point I have been trying to make is that I would not need the additional legislation to be able to get rid of the way that stop-and-frisk has been misused. I would not allow people to be, in the city of New York, to be profiled. If you allowed that, you wouldn't be my police commissioner. I would terminate my police commissioner.

GG: Looking at Bloomberg's legacy on education, what policies would you keep? What would you reject?

BT: I would give the mayor credit for seeking mayoral control and for getting it. I've been supportive. I've testified in front of the City Council when it was moving forward. I think he should be given credit for getting mayoral control.

I think for looking to try to reform things and change bureaucracy, I will give [him] credit for that. And for the focus on education, attempting to be the education mayor. I will give him credit for that.

On the other side, I think they have failed in a number of ways when it comes to education. The excessive focus on standardized testing. Robbing the school system of content. In a lot of ways sacrificing it for, in search of, better scores on standardized testing is a mistake. And also underestimating how important it is to afford an educational vision and have an educator at the head of the system. That's one of the things I've said I would do. I want to have a chancellor who is an educator. Who is a classroom teacher. Who understands the structure. Who knows how to put forward a strong educational vision for the City of New York. Who knows how to engage people. We haven't seen that in many years.

GG: Turning to sustainability, would you, as mayor, call for a retreat from the coastline?

BT: There's not a one size fits all. If you look at some places like Sea Gate, where someone has said "Wow, it's flooded before,” they'll talk to you about the need to do more seawalls, or seawalls again. But seawalls got breached. But it's an opportunity to rebuild. Coney Island? We're not going to walk away from Coney Island. At the same point, what can you do differently?

Things I've recommended that I want to do: a deputy mayor for infrastructure and construction. There's an opportunity to coordinate this. We're getting money from the federal government and from FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Administration]. You have city capital dollars. There's money from the state. Private dollars. Dollars from utilities. We need to coordinate this. So that when you look at neighborhoods, when you look at seaside comminutes … making sure that in the next extreme weather pattern, they are prepared. So you're not going to rebuild everything at once. It just doesn't make sense.

GG: As comptroller, what do you think were your top three achievements?

BT: I think that it was an office that was a different office when I left. That was a more aggressive office. That it was an office that involved itself in things other than the bottom line.

Whether it was working in shareholder rights on one side, being an incredibly aggressive office … whether it was a comptroller that got involved in education, public safety, you name it, there wasn't an issue that the office didn’t get involved in. And before I was there? It was … the comptroller was involved in the books and the bottom line and a bunch of other things. After that? It was an activist office.

I was a frequent critic of some of the direction we were going in, and there was a question of fairness and equity across the city. You talk about budget cuts cross the boroughs ... You looked at neighborhoods and crime was going up in neighborhoods, I had no difficulty talking about that.

GG: How would you as mayor relate with the comptroller's office?

BT: It's starting out with a healthy, respectful comptroller's office as an institution, and understanding that we're not always going to be on the same page. There is some … almost built-in tension between the office of the comptroller and the mayor … and there are a lot of things that you can work on together. But you are going to disagree and you are going to bump heads. That's just kind of the nature of the job.

GG: What would you do about a comptroller who seeks to make the office even more of a platform, who is even more aggressive? How do you deal with that as mayor without there being political gridlock?

BT: The one thing about the system? It's designed to prevent gridlock. One of the things I found frustrating, as comptroller is that sometimes, even if you disagreed, the mayor can move forward. It is a very strong structure.

GG: A lot of people say Bill Thompson’s a “really mild guy, he doesn't stand out to me.” What do you think stands out about you?

BT: Perhaps the one thing that's overlooked, on behalf of the people of the City of New York, on issues of principle, I will always stand up. I was at the Board of Education as its president, and took on Rudy Giuliani. People believed he couldn't be beat over who the next chancellor of the education system was. And I stood up in spite of the fact that people thought I was crazy for doing that. It was the right thing to do. It was what made sense for our children.

I've always led, and I've never been scared to lead the city. I wouldn't end up being the mayor who screamed at people, but I would be the mayor who stood for the people of the city.

South Asians See 'Tipping Point' In 2013 NYC Elections

NEW YORK — In the early 1970s, Amol Sinha’s parents moved to the United States from the state of Bihar, India. Sinha’s father came to pursue an education and later work as a statistician. His mother stayed home to raise their three U.S.-born sons.

When Sinha’s parents came to the U.S., the South Asian community was disparate and far-flung. South Asians lived in small, isolated areas, and rarely saw other people who looked liked them in their daily lives. Over the next 40 years, the Sinhas saw their fellow South Asians grow in number, form enclaves and flourish in fields such as science, technology, law and business. At 28, Sinha is a lawyer with the New York Civil Liberties Union. His two older brothers are doctors.

But while South Asians have succeeded in a wide variety of industries in the city, Sinha said he longs to be able to call a city elected official one of his own. There is currently no South Asian on the City Council or in citywide office. That could change this year, with a number of South Asian candidates running for Council and — perhaps most notably — Reshma Saujani in a tough race for the citywide office of public advocate.

“To see somebody take a risk and actually do things to serve communities in public interest, or public service, is certainly inspiring and motivational,” Sinha said. “And the more that becomes the norm, the better it will be.”

But while some South Asian candidates say this year could be a “tipping point,” and the 2010 Census puts the population of South Asians in New York City at a robust 300,000 or more, there is no guarantee of victory at the polls.

Activist groups say that this is in large part due to the way district lines have been redrawn, splitting up South Asian communities of interest. There is also the fact that the South Asian community in itself is not a monolithic mass.

The community encompasses a number of diverse cultures, languages and religions: Someone of South Asian descent could be from a whole host of different countries, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bhutan, as well as countries with large diaspora populations, like Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname and Uganda.

So how can a South Asian candidate win in this election season?

Saujani, an Indian-American who previously launched the nonprofit tech organization Girls Who Code and served as deputy public advocate, said it was critical to campaign for more than just the South Asian community if she is to have a chance at getting elected.

“So it’s not like, ‘You’re Asian so I’ll vote for you, or you’re black so I’ll vote for you,’” Saujani said. “It’s, ‘Will you fight for my issues?’” And Saujani, whose family came to New York from Uganda as refugees, said she inherently understands these issues due to her background.

“I think the powerful thing you’re seeing with this next generation of leadership is many of us are first-generation Americans,” she said. “We’re so tied to the American dream, so tied to creating the American dream.”

Saujani’s opponents include politically influential Councilwoman Letitia James and state Sen. Daniel Squadron. Saujani is very much the outsider candidate, with not as much name recognition as her two opponents. That said, when the deadline came for candidates to file their petition to get on the ballot, Saujani’s campaign said they filed over 45,000 signatures — 12 times the required 3,750. Of course, not to be outdone in the slightest, James’ campaign said they filed around 70,000.

But Saujani’s campaign manager, Michael Blake, a former aide to both Obama campaigns, is not worried. He said she will “absolutely” win.

“She is not just coming at it in a policy perspective, she’s coming at it in a personal way,” Blake said. “And people understand that, they relate to that.” Saujani’s background and immigrant status is key to the way her campaign is engaging with voters. This is perhaps an effort to use her outsider status as an advantage, by saying that this is a candidate not entrenched in the political system.

“This is a citywide grassroots organization in the same way we built the Obama model, which clearly worked,” Blake said. “We’re going to do that here.”

John Albert, an organizer with Taking Our Seat, which seeks to empower South Asian voters, said finding unifying themes in the American political context could mean all the difference for candidates between winning and losing. Forming coalitions of voters has long been considered the road to elected office in such an ethnically diverse city as New York.

“I think the South Asian community poses some unique challenges,” Albert said. “We’re fractured in so many more pieces. There may be different types of Latinos, but Spanish brings them together. We don’t have that particular connection.”

Some South Asian candidates argue, though, that the lines of division within the South Asian community in the city are much more blurred than the borders between those of its home countries.

One prominent South Asian candidate who recently bowed out of the election is Abe George, who was running to be the next Brooklyn district attorney against longtime incumbent Charles Hynes.

“You come to Brooklyn and, on Coney Island Avenue, the Pakistanis and the Hindus are getting along,” George told the Gotham Gazette before deciding to drop out of the race last week and endorsing his opponent, Kenneth Thompson. “But you go to India, and the Pakistanis and the Indians are fighting. I think it’s different here in America because we’re so outnumbered that you come together.”

Regardless, Albert said, overcoming potential differences within the community is hugely important because of the power in numbers.

“Much of our work early on was to go to communities and say, ‘Yes, you can be Bangladeshi, you can be Pakistani, you can be Punjabi,’” he said. “But it’s more politically empowering to say we’re South Asian.”

Candidates are also running on platforms that they hope will attract the minority vote in general. Albert says that, strategically, it is important for them to focus on Hispanic and black communities.

“We have to have an understanding that the South Asian community lives very close to the Latino community,” Albert said. “You’re more likely to have a Latino neighbor than anything.”

George, for example, was running a campaign that was strongly against the aggressive stop-and-frisk tactics of the New York Police Department, which have long been seen as targeted at blacks and Latinos. He had said that marijuana cases were a waste of time, and had he been elected, he wouldn’t have prosecuted anyone carrying only a small amount.

“I’m not going to wait for the state Legislature,” George had said, referring to efforts on the state level to pass a law that would decrease penalties for the possession of small amounts of marijuana. “I’m going to decide right now that I’m not going to prosecute those cases as a crime. Just as a violation. I’ve got bigger fish to fry.”

But Hynes said his office already didn’t prosecute for possession of small amounts of marijuana, during the first debate of the race. George called Hynes “a liar” when he said this. Regardless, not long after the debate, the pro-legalization National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws endorsed George over Hynes.

Helal Sheikh, a Bangladeshi former public school teacher from East New York who is running to represent the 37th City Council District, said he was very keen on capturing Latino and black votes. He said that if he were to just focus on the South Asian vote that the numbers in his district wouldn’t be there to get him elected, despite the large number of Bangladeshis who reside in East New York.

He also emphasized the importance of the South Asian community finally seeing political representation, but added that electing the most qualified candidate was still more important.

“I’m not running as a Muslim,” Sheikh said. “I don’t want anyone’s vote as a Muslim.”

First generation American candidates will also need to target the first-time voter base. South Asian candidates said they need to not simply campaign on the issues, but also spend some of their time and resources on get-out-the-vote strategies.

Adding to the challenges is the language barrier at the ballot box. While the city Board of Elections is mandated under the Voting Rights Act to provide ballots in Bengali to some of Queens, there is no requirement for Hindi or other major South Asian languages. Some candidates are doing voter outreach, alongside campaigning, to try and engage people in an effort to overcome the difficulties the South Asian community might face on Election Day.

“I’m going door-to-door, and asking who’s registered and who’s not,” Sheikh said, adding that he is working hard to get people registered to vote in his neighborhood. Sheikh said he believes his race will be decided in the primary, and that therefore a strategy that focuses on getting as many people registered as possible could tip the scales for him.

Natraj Bhushan, a lawyer with the Community Resource Legal Network who is running for the 48th City Council District, agreed that registering voters was critical for a win on Election Day. But he said that as a younger candidate — he is 28 years old — getting help from older and more experienced candidates had been very helpful when focusing on these types of strategies.

“To pick their brains, to know that anything can be accomplished in numbers is invaluable,” Bhushan said. He went on to add that he had even been discussing potentially sharing election lawyers with others.

Above all, South Asian community members and candidates stressed the significance of the symbolism of electing one of their own to office.

“I just think it’s important for someone to represent me for a change as well, somebody who looks like me,” said Neha Dewan, a lawyer who works at the city’s Department of Education. “I’d also like to see someone who looks like me pave the path for other people.”

Bhushan agreed, and said that this election is a “tipping point” for the South Asian community.

“If you would have spoke to me maybe four years ago I would have said, ‘Yeah, it may be a little raw. We’re testing the waters,’” he said. But he said he feels that the time is ripe now, and that someone from the South Asian community will hold city office by the end of this election cycle.

“Whether it’s myself or whether it’s another individual, I think the word trailblazer comes to mind,” Bhushan said. “We’re talking about opening doors to future generations of candidates.”

Sinha said seeing someone from his community elected to office would also mean a lot for how South Asian voters — or South Asians who have yet to register to vote — would view politics going into the future.

“Being politically engaged or being engaged in the democratic process has in a way been seen as a white thing,” he said. “Over the years it’s been seen as something that isn’t necessarily for us.”

Sinha added, “It’s incumbent upon those candidates to cut away at the apathy that might exist.”

Minty Grover is a freelance broadcast and print journalist living in New York. Her work has appeared in both local and international news outlets.

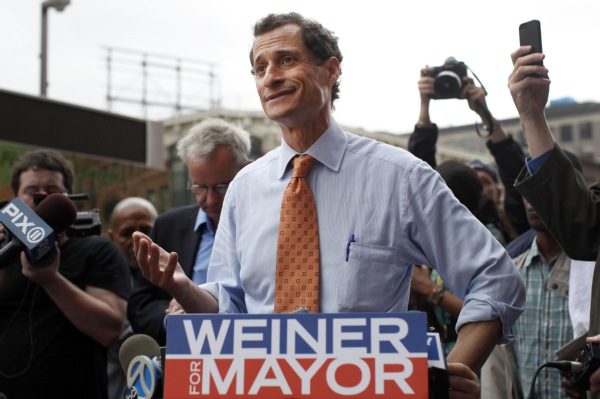

GothamVotes: 30 Minutes With Anthony Weiner

NEW YORK — Anthony Weiner may consider himself the underdog in this year's mayoral race. But his strong poll numbers from the outset of his late entry belie that idea.

Despite the sexting scandal that led him to resign from Congress two years ago, Weiner remains a credible Democratic mayoral candidate. The self-styled policy wonk has said his focus on ideas for making life better for the middle class will take him all the way to Gracie Mansion.

Those ideas were largely outlined in a policy briefing, called “Keys to the City,” which he released even before entering the mayoral race. While the booklet draws from a handful of concepts he floated the last time he considered a run for City Hall back in 2005, there are a number of new ones (e.g., Kindles for every New York City school child). In our recent exclusive interview with the candidate, Weiner elaborated on his policy ideas and answered questions about public safety, the city budget and more.

GOTHAM GAZETTE: The first chapter in your "Keys to the City" is on education. After three terms of a mayor who did a lot to boost the Department of Education by bridging it with the private sector, is that relationship something you'd keep?

ANTHONY WEINER: Well, there have been a lot of instances where the mayor's business background has been an obstacle to him understanding some of the elements of government and education. There have been clearly some example where his relationship with other rich people and the corporate world has been a great benefit to New York City, and one of them is the way he's been able to persuade some of these business and individuals to get involved.

I hope to continue that kind of thing. I need to bring resources — whether they be from Washington, Albany or from individuals who just care about the future of New York City.

Now you can quibble or disagree about where he chose to focus, but I don't think that should diminish the appreciation New Yorkers should have — that he's devoted a lot of energy to trying to get private sector investment in New York City on a lot of levels.

GG: One of the things that your policy book makes a point of is your strong advocacy of school choice and changing how the city might work with teachers going forward — one of the points in the book is reformulating how we do teacher contracts. With the next mayor likely to be the one to deal with contract negotiations, how do you think those ideas will play?

AW: I'm not going to litigate some of the terms you've used. You know, a strong advocate for school choice — that means I'm a strong advocate of charters. That's not really the case. I'm kind of agnostic. I want to figure out whatever works. But I don't think I'm someone who goes out an campaigns on the idea of charters. I'm just not ideologically opposed to them.

And in terms of the ideas that I've talked about — returning a sense of discipline to the classrooms, and trying to give teachers more mobility and trying to give me as the the mayor, hopefully, more flexibility on where I send teachers. I think these are things that most teachers want. I think most teachers by and large want to have raises, they want to have health care that's affordable. They also want to be rewarded for the work that they do.

So I don't think I'm going to have any more difficulty than any other executive has in negotiating contracts with their workers … I'd like to be able to afford to give raises, but I can't do it unless I fix health care. That's not a confrontational concept; those are the facts, and I think most union members and the leadership understand the facts.

GG: One of Mayor Bloomberg's legacies will be reconstruction post-Superstorm Sandy and the resiliency plan, and he's been a strong defender of the city's right to redevelop on its waterfronts.

AW: Retreat really isn't an option. Our waterfront is not only valuable real estate, but it's people's home. Simply saying that we're going to have wholesale rezoning that is going to limit development in places we already have — that doesn't mean we've made smart decisions up to now — but I think the mayor has set us on a good path to at least give this a good deal of thought.

There are things that I think we need to perhaps do differently. In fairness, it's not going to be him doing it. It's going to be the next two or three mayors probably. But he's absolutely right to call attention to the idea that we can't keep doing things the way we did them in the 1930s and 1940s.

GG: You've recently suggested that the state of ethics in Albany makes the case for New York to take back some its control of a realm of issues. But the city's been dealing with its own share corruption investigations. Do you think the city's Department of Investigation has enough teeth to handle the spate of scandals?

AW: Let me just make one thing clear: my declaration of independence from Albany didn't have a lot to do with scandal. It was more about the dysfunctional nature of the government there and the relatively good functioning government that we have here.

All that being said, I think the Department of Investigations — I think the tools are available to a mayor to weed out corruption in his administration. We've had a lot of conversation about challenges facing the police department: the criminal justice coordinator, the CCRB, the Corporation Counsel. There's all kinds of legal remedies if you're serious about weeding out corruption.

I think when you have a city bureaucracy as large as the one we have, you have to assume there will be some bad apples in the bunch, and the real challenge for any mayor is how swiftly those things are dealt with. I hope to run an administration where we never have any investigations by DOI, but I'm going to put someone there who's independent, who's given a broad and clear mandate to weed out trouble wherever they find it. And I'm going to back them up on it. It's not going to be a second-tier appointment for me.

GG: Pending any litigation or an actual mayoral veto, the NYPD inspector general bill leaves it up to the mayor to appoint the IG.

AW: Well, I don't support the legislation, but I believe in following the law. And if this is created by the Legislature, I will fill it. But I also don't believe it will be necessary in my administration.

GG: Would that be one of the second-tier appointments?

AW: There aren't going to be second-tier … I guess you caught me in a rhetorical trap that I have implied that there are. No, it would not be. I'm going to have good people working for the people of the city of New York. But I will make it clear that the policies that the inspector general is intended to address, I will change without the help of any inspector general.

GG: Another issue that you bring up in the policy book is the city budget, namely making it more transparent and open to taxpayers. Some groups ask if the city's Office of Management and Budget has operated in a somewhat unaccountable way.

AW: You know, the Independent Budget Office was created because of this sense that we needed some structural alternative to OMB. Let's face it: in our charter, the single greatest power the mayor may have above all else is his ability to estimate revenues. So when you have that much power in an agency, you need to balance it with some level of transparency or at least some fulcrum on the other side.

Now, we haven't had a strong fulcrum on the other side because the Council has largely gone along with the mayor. I hope that my OMB is on the level, and that the data that they use is transparent. I hope that we have a conversation that's more honest around things like revenue from fines and levies, whether or not it's leading to summons activities just to meet the OMBs targets.

GG: What's your take on member items: keep them, reform them, do away with them?

AW: Again, there's a real transparency problem above all else. I think that member items should be administered as a process through the executive branch, because it's pretty clear the legislative branch is using them for political purposes and not necessarily the best interest of the citizens. Some of them are going towards worthy organizations, some not.

You have some vetting process of the organization as a stage one of the process. Second, something like what was done in Congress where every request that comes to a member of Congress to the speaker has to be public in some way before the budget is done. And, finally, Council members should not be allowed to fundraise from those organization once that conflict has been established. Money should not be able to come back from the people who are involved in the organizations because they got taxpayer dollars.

GG: Housing in New York City has long been one of the markers of inequality in the city. As someone who's trying to help "build the middle class," how do you make an agency like NYCHA more accountable to taxpayers and tenants?

AW: The fact that you have this trifurcated structure of federal, state and city funding coming to NYCHA, you have no true accountably, and you have very few incentives on improving what goes on in public housing.

We have to at some point have a conversation ... with the state and the feds to say that if we're able to make this more efficient, it got to benefit the residents of the project. I was the chairman of the Subcommittee on Safety in Public Housing in the late 90s, and one of the reasons I took that assignment was because no one was fighting for NYCHA residents. There wasn't much accountability. That has to obviously change. But was also have to do other things.

We have to realize that one of the reasons that we've had so much strain on public housing is that we haven't done what we needed to give people ladders of opportunity to leave public housing and to move into other programs like the Nehemiah or Mitchell-Lama program for the 21st century.

GG: So how do you balance the need for help from the other level of government with taking sovereignty on New York City issues?

AW: Well, look: what I have found — Medicaid is a good example — if you say to your partner in government, in this case the federal government, "we want to innovate, we want to come up with a plan that saves people people and gets better healthcare," by and large Washington says, "okay, we'll give you that waiver and let's see how it works."

I think the general footing is usually with governments, whether it be the state or federal government, people want the best outcomes. And it starts with having innovative ideas on how you improve outcomes. That's the first step in persuading our colleagues on other levels of government to let us take more control.

Right now, there's not a lot of innovation going on because there's not much premium for innovation the way things are structured now.

Spitzer's Call For A Bolder Comptroller Sounds Familiar

NEW YORK — Eliot Spitzer has said that if he is elected comptroller he will use the powers of the office aggressively, bringing the same brand of prosecutorial zeal to the job that made him feared on Wall Street.

The comptroller’s office, he has said in interview after interview, does more than just count how many paper clips were bought and delivered. The office has untapped political power to shape urban policy.

New York City voters have heard similar sentiments in the past.

At his 2010 inauguration, current Comptroller John Liu said he would leverage the powers of the office “in the most robust manner for the city” and would “maximize” its potential. Liu’s predecessor was more explicit four years earlier. "I entered office determined to be an activist comptroller," said a victorious Bill Thompson during his second inauguration in 2006, "by aggressively using the powers of my office to find new, creative ways to save the taxpayers money and to put our resources to work for all New Yorkers."

Spitzer’s take on the powers of the city's chief financial officer immediately grabbed headlines. Spectators argued that if anybody could grow the role of the comptroller's office, the steamroller could. But those arguments discounted the fact that the comptroller's office has long enjoyed a strong role in policymaking, and that the degree and intensity with which it drives policy depends on who is at the wheel.

"You can't always separate finances from policy," said Liz Holtzman, a former comptroller and congresswoman. "It's not anything new. The question is the comptroller's priority and vision."

And while past comptrollers have long championed policy causes, they have also couched their successes on their ability to build consensus — a trait that has never been seen as one of Spitzer’s strongest.

One of only three citywide elected seats in New York City, the comptroller is in charge of making sure that the city is in good financial health. He or she looks at the city budget every year, advising both the mayor and the City Council.

Lacking the singular power of the mayor or the ambiguity of the public advocate, a comptroller’s success can actually be quantified: He or she is tasked with overseeing and maximizing $139.2 billion in pension funds for retired teachers, police officers, firefighters and other municipal workers. The office does give comptrollers latitude with investment and divestment power, which can be used to pressure or reward companies on issues relevant to their industries.

In May, Liu, who is running for mayor, announced that at least one of the city’s pension funds had fully divested its stock holdings of publicly traded gun and ammunition manufacturers after the mass shooting at an elementary school in Sandy Hook, Conn. The fund withdrew its money from five companies at a combined value of more than $16 million.

But influence over the pensions is merely one tool that comptrollers wield. They are also responsible for auditing city agencies and for making sure that contracts that the city enters into are fiscally solvent and responsible. While comptrollers can’t be entirely selective about what or who they audit, they are given some leeway.

While Spitzer's campaign did not reply to multiple inquiries from Gotham Gazette, recent interviews with former comptrollers and advocates provided a view into one of the least well known elected offices in the city and how it can be used as a tool.

The most successful comptrollers use their auditing powers to help recoup funds for the city, argued Maria Doulis of the Citizens Budget Committee, as well as how the office issues bonds to refinance the city's debt.

"Comptrollers have a lot of responsibility," Doulis said. "It's just that it's not in the limelight."

That may not be the case if Spitzer wins the Democratic primary. Still, Spitzer has yet to define exactly what policy realms he would weigh in on as comptroller other than his stock in trade on corporate oversight and public education.

During his time as governor-elect, Spitzer celebrated a 2006 court decision that promised billions in required funding for New York City schools.

"As I said at the time, and I believe just as deeply now, spending the money is the easy part," Spitzer said during an interview last week with WNYC’s Brian Lehrer, during which the former governor repeated his promise to look at education spending. "Making sure you're doing wisely is the much more difficult part."

During the same interview, however, Spitzer belied his own headline-making claims and admitted that there's been a long tradition of comptrollers active in social policy. In fact, he said, the power is already enshrined in the city's governing document. "The courts have interpreted the audit power of the comptroller to extend to that type of substantive conversation,” he said.

Whatever Spitzer may have in store for the comptroller’s seat, he's not the only one with a policy record hoping to take the seat.

Previously the leading and lone Democrat in the race, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer said that nothing that Spitzer has proposed is groundbreaking.

"That's an obligation — that's a great tradition — of this job," Stringer told the Gotham Gazette, explaining that the city has helped shape corporate and social justice reform, including in the 1980s when the city used its pension to companies against selling products to South Africa during apartheid.

"I've been doing these proposals and this work for many years," said Stringer, a former assemblyman and a sitting trustee on the New York City Employees' Retirement System. "But I welcome my opponent, who is new to this."

Either Stringer or Spitzer would face Wall Street executive-turned-Republican candidate John Burnett and Kristin Davis, the "Manhattan Madam" currently running on the Libertarian ticket.

At least one former comptroller agrees with Stringer that the office is already a strong platform for advocacy.

"There's a lot of power in the office to begin with," said mayoral candidate Bill Thompson at a press event last week. "There's a lot of power in the office right now that can harnessed on behalf of the people of the city of New York by whoever the next comptroller is."

Some question if Thompson himself exerted his fullest potential as comptroller during his two terms. After Thompson lost his 2009 mayoral bid to Michael Bloomberg, City Limits revealed that the comptroller's office under his watch had filed 626 audits since taking office in 2002.

Most of those, however, took place at the beginning of his term, and average about 80 audits a year between 2005 and 2008. Comparatively, that's still more than his replacement and mayoral rival, John Liu, who has fluctuated between 60 and 80 audits a year since taking office in 2009.

Even so, one of Liu's audits was also one of the city's most damning in recent history. His 2011 audit of the Bloomberg administration’s automated payroll system known as CityTime revealed that what started out as a $70 million contract exploded to more than $700 million. The city eventually managed to recoup $500 million.

Liu also hasn't shied away from being a counterweight to the mayor's office or Wall Street, especially on social policy issues.

In addition to helping pave the way for the divestment from gun manufacturers earlier this year, Liu has sharply criticized American companies that employ labor in unsafe Bangladeshi factories.

And the comptroller helped lead the (so far unsuccessful) charge against JPMorgan Chase — with which the city has $500 million invested — to wrestle away at least one job title from the bank's Chief Executive and Chairman Jamie Dimon in the wake of its $6 billion in losses over the so-called London Whale trading scandal.

He's even managed to turn the financial impact of misconduct complaints against the New York Police Department into a solid platform against the city's controversial stop-and-frisk policy. Liu is the singular mayoral candidate in 2013 promising to eradicate the policy — which has brought him in conflict with Police Commissioner Ray Kelly and Bloomberg.

"The goal is not to be at odds with the mayor's office, although at times it may be," said Deputy Comptroller Ari Hoffnung, who has worked under Liu since he took over the office.

The political reality is that while the city charter doesn't explicitly enumerate policy powers, it's unavoidable that the person heading the city' purse strings would have some say on how that money is spent.

"The office forces you to be a critical player in a number of issues," said Holtzman, who many political observers celebrate as a proactive and independent comptroller.

She was no stranger to the policy debate. Serving between 1990 and 1993, Holtzman came into the office after serving eight years in the House of Representatives and another eight as Brooklyn district attorney.

By 1992, that policy acumen helped her stall plans to build a new garbage incinerator, which would have cost the city a $1 billion contract and countless health issues for New Yorkers.

"We issued those reports — they undergirded those efforts," she told the Gazette, recalling the letter she wrote to then-Mayor David Dinkins and the City Council that listed violations of environmental and corruption laws by the company that was hoping to build to incinerator.

"We did very important policy work on some big-ticket items," Holtzman added. "The office has the capability of doing that."

She also recognized that her office had more power back before her; Holtzman came into office right after the city revised its charter to eliminate the Board of Estimate.

In 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the eight-member panel — on which the comptroller sat in along with the mayor, the Council leader and five borough presidents — violated the Constitution's equal protection clause.

That didn't stop Holtzman from figuring out how to best influence urban policy.

Before she lobbied against the incinerator, she also helped steer the national conversation on environmentalism. Barely three months into her term as comptroller, she used joined other comptrollers from major cities to pressure the Exxon oil company to address concerns after the Exxon-Valdez spill.

She even laid the groundwork for a bill to make gun manufacturers and dealers liable for harm or death caused in the course of a criminal act. Drafting the bill in 1995, Mayor Bloomberg signed the bill 10 years later.

While the comptroller's office still holds considerable power and influence on how the city administers much of its money and, as a result, general urban policy, cooperation and the ability to compromise is also key to the job.

"You're a steward, a custodian, in a lot of key areas," said Gerrard Patrick Bushell, a former director of intergovernmental relations for state Comptroller H. Carl McCall.

Bushell, a board member of Gotham Gazette's sister organization Citizens Union, described how a comptroller needs to bring about consensus amongst a large group of strong-willed individuals.

A comptroller is only one voice of many on the pension boards; has to work with scores of agency heads to properly conduct audits; and submits recommendations to a budget handled by countless City Hall staffers and leaders.

"The comptroller doesn't exist outside of other players in the city," he said, especially in a city with strong mayoral influence.

For Scott Stringer, it means that being the sheriff might be somewhat overrated.

"This is a job where you can't be a lone ranger," Stringer said. "You have to be someone who can be collaborative."

Stringer can already count on that spirit of collaboration with at least three Democratic mayoral hopefuls. Besides Thompson, Public Advocate Bill de Blasio and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn have rallied behind the outgoing borough president.

(Liu, while not publicly endorsing Stringer, recently said that he's "incensed for the sheer disrespect" that Spitzer's bid for comptroller and former Congressman Anthony Weiner's mayoral run show towards New York City women. Quinn has made similar statements of her own.)

It remains to be seen just how well Spitzer can play with others as comptroller. His record certainly shows a streak of independence and willingness to take on the political establishment.

The question is whether he can reconcile that with his appetite for conflict and uncompromising passion for winning — an image that he's tried to shed in recent days with a more humbled tone.

Regardless of who becomes the city's next comptroller, Holtzman suggested that the office requires that delicate balance between independence and cooperation with other agencies and leadership for the city's overall benefit.

"You can't just be out there and spit at the mayor," she said. “It's not going to work."

Questions For Republican Mayoral Candidate Joe Lhota

NEW YORK — Joe Lhota, the Republican mayoral candidate whose leadership of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has been credited with helping to stave off calamity to the city's subway system during Hurricane Sandy last year, is often considered a seasoned manager of large, untidy bureaucracies. It is a well-deserved reputation. He held positions in the Rudy Giuliani administration, including as budget director and deputy mayor of operations. He was MTA chief from 2011 to 2012. During an interview with the Gotham Gazette at his campaign office near Grand Central Terminal, he responded to questions on various public policy issues, from the budget to the Community Safety Act (which he called the "Community Un-Safety Act").

GG: The City Council and mayor recently approved a new city budget, so that seems like a good place to start. Do you think the so-called “budget dance” is a distraction from actual debate about budget priorities?

LHOTA: See, I look at the dance as starting in January. When the public talks about the dance, they are really just talking about what they think is what happens in regards to the executive budget in connection with member items, which is just a minor, minor piece, about $300 to $400 million dollars. And quite honestly, that budget dance starts at the beginning. The city charter, the lowercase “c” constitution of the city, lays out the process for the dance.

GG: So you’re not critical of the budget dance?

LHOTA: I’m not critical of the budget process at all.

GG: What do you think of the way that discretionary funding is distributed to City Council members for their district?

LHOTA: Some members, some people running for mayor have actually called for the end of Council member items. I'm not at that level yet. I think it … needs to be open and transparent.

GG: The city’s open data law is a national model. What would you do to make sure that the city continues to be at the forefront of the open government movement, and how would you get agencies to comply with the law?