Behind the Hate Crimes on Staten Island

Let’s start with this inescapable fact: If you are a Mexican immigrant living in Port Richmond on Staten Island you are being targeted by some black young people.

There have been 11 such attacks since April and another on a white gay married couple. The violence has attracted citywide and national attention in what is being called an epidemic of bias-related crime. Such assaults are proliferating on Staten Island’s North Shore.

These incidents have revived debates over what constitutes a hate crime, whether these attacks are borne out of bias, whether enhanced penalties are just and effective, the roots of the tensions, and what the response should be.

I write as a Manhattanite who has done work and played on Staten Island but who must relay mostly on the testimony of native islanders to get this story.

It turns out that the tensions are by no means a new story, even the black-on-Mexican attacks in Port Richmond. Debbie Nathan documented similar neighborhood conflicts for City Limits in an article called "Race Wars" in 2004, questioning the “hate crime” paradigm.

But never has more attention been paid to it.

The Tensions Beneath

Staten Island has changed over the years from a bastion of insular white conservatism to a multiracial borough with an increasingly progressive bent. You only have to ride the Staten Island Ferry -- as I did on a recent Saturday night -- to see African Americans, Latinos and Asian residents.

The boat I rode was named for former Staten Island Borough President Guy Molinari. In 1994, he infamously declared Karen Burstein, the Democratic nominee for state attorney general, “unfit for public office” because she was a lesbian. Today one of Staten Island’s Assembly members, Matthew Titone, is an out gay man and one of its City Council members, Debi Rose, is African American.

And Staten Islanders embrace this.

A white woman on the ferry named Israela called the current crisis “crazy.” She said of the perpetrators, “Their parents should talk to them.”

Daphne Burton, an African American woman from Queens going to the island for a visit with her grown children, said of the situation, “We all have a right to be free, but a lot of people don’t look at it like that.”

Staten Islanders and public officials have turned out in force to denounce the attacks. A broad and diverse coalition of elected officials and groups has started the “I Am Staten Island” campaign to “take responsibility for ensuring the Island is a safe and welcoming borough for people of all backgrounds.” Their 10-point plan to address the crisis includes public and school education programs on tolerance, installing more security cameras, aiding attack victims, increasing recreational opportunities in the affected neighborhoods, and expanding intergroup relations efforts by religious groups and other community-based organizations.

As laudable as these efforts may be, they may not get to the heart of the problem or reach the young people behind the violence, some longtime residents and advocates say. Ana Maria Archila, co-executive director of Make the Road by Walking, an advocacy group with a presence on Staten Island, says Port Richmond’s is afflicted with a “total abandonment by government,” “disaffected African American youth” who have no employment or hope, “the fastest growing Mexican community in the city,” and a lot of “confusion and resentment.” She sees the current wave of violence as an outgrowth of anti-immigrant campaigns across the country.

“Every community has bad apples,” said Assemblymember Titone. But, he added, “Thugs probably don’t go to church and school and can’t be reached. They need to be apprehended.”

Council Speaker Christine Quinn, a former director of the Gay and Lesbian Anti-Violence Project, said that it is difficult to determine the source of this wave of violence. It could be economic factors, although theft did not occur in four of the 11 attacks. Nonetheless, she said, “No one should think we only have a problem on Staten Island.”

"A large response from all parts of society is a good thing because it sends a message to everyone who might want to act out against immigrants that the City of New York absolutely will not tolerate it,” Quinn said. She noted the I Am Staten Island group includes everyone from gay and lesbian groups to the Sons of Italy.

A Full Swing Response

The City and the FBI have responded with an increased police presence in Port Richmond.

But the most recent attack on a Mexican, Christian VĂ zquez, 18, occurred on July 31 while the show of force was in full swing. Police later arrested a suspect in that case, Derrian Williams a.k.a Romeo Stevens-- a 17-year-old Liberian immigrant. He faces 25 years in prison if convicted of all robbery and assault charges -- each charge could include additional prison time because his assault is classified as a hate crime. Police believe five men were involved in the attack.

The police response has not pleased everyone.

Archila of Make the Road said the constant police presence has hurt Mexican businesses whose customers, some of whom are here illegally, shy away from law enforcement. “There’s less crime,” she said, “but it doesn’t feel sustainable.”

Others question whether singling out these crimes is the best strategy.

Bill Dobbs, a longtime gay and civil liberties activist, said, “Criminal law cannot fix social problems. The cry for hate crime prosecutions is raised once again in Port Richmond but it cannot reckon with race relations or intergroup tensions. That requires hard work and community intervention Using the New York hate crimes statute also contains the seeds for backlash, creating resentment that some criminal acts are punished more severely because certain words were spoken during the crime.”

In the Other Boroughs

Crime is up in most categories across the city, but hate crimes have increased disproportionately citywide. According to the Daily News, hate crimes jumped from “111 to 200 through July 11 -- an 80 percent surge from the same time period in 2009.”

The police department did not respond to several requests for a breakdown of hate crimes statistics by borough. A representative from the Hate Crimes Bureau itself said it does not give those statistics out. According to the Wall Street Journal, there were 21 bias-related crimes so far this year on Staten Island versus nine over the same time period last year.

Crime overall is climbing on Staten Island. From mid-July to early August, the number of murders was up 150 percent and robbery is up 100 percent compared to the same time period in 2009. The increase is almost all within the 120th Precinct on the North Shore. Citywide the murder rate is up 3.4 percent and robberies 6.4 percent over the same time period.

Some of the spike in reported hate crimes may have to do with the public attention and official encouragement to report them. Maria Morales, who runs a taqueria in Port Richmond, told the Journal that she believes it is the reporting that is up, not the number of incidents.

Behind the Crimes

Some speculate the attacks are part of a gang initiation. Others call some of them “crimes of opportunity” -- when youthful offenders prey on Mexican day laborers coming home late at night with cash in their pockets. The explanations have not warmed the chilling effect of the crimes on the Mexican and gay communities on Staten Island.

Alejandro Galindo, 52, was attacked by four black men on June 24 while riding his bike home from his job as a dishwasher. He told the News that he could not explain the attack. His daughter, Blanca Galindo, told the paper, “He still lives in fear. They did not take anything. He was attacked just for being who he is.”

There is no doubt that the attack on Richard and Luis Viera, 13-year residents of Staten Island, at the Stapleton White Castle in July was unequivocally an anti-gay hate crime. As they ate very late one night, a group of teens came in and said to Luis: “What the fuck are you looking at, faggot?” and then hit him on the back of the head.

When the couple followed the attacker out to the parking lot, more than a dozen teens surrounded them. Luis was able to run back into the restaurant, but Richard was beaten, leaving him with multiple bruises and ongoing dizziness. (White Castle, whose employees did nothing to aid the men on the night of the attack, sent them a corporate letter offering them a free meal!)

Luis wrote in an e-mail that, other than the Hate Crimes Task Force, “no other police outreach ever made an attempt to assist us. On Staten Island the local police are very close-knit unit, and dealing with these issues and other ethnic issues is of the least importance to their daily work assignments. The mentality here on Staten Island is one of ignorance, which I was quite familiar with having grown up in a small town in Alabama during the '70s and 80s.”

A Night Out Against Hate

Staten Islanders are trying to fight back. Richard Veira was among those who participated in a march against hate crimes in early August. The march ended at the now-infamous White Castle.

While there, he said, “It’s not a gay cause. It’s a human issue. If I give in to fear, fear will win. I’ve got too much life to live.” He acknowledges that hate crimes don’t happen in a vacuum, citing the terrible economy and the lack of constructive outlets for these young people.

At 2 a.m. the night before this march, community members held a vigil at the White Castle to counter the idea that gay people would be cowed into not going out at night.

Jim Smith, who was the grand marshal of the first Staten Island gay pride parade in 2005 and grew up in West Brighton, said the gathering “was amazing. There were packs of young people in groups of 20 to 30 -- probably looking for trouble and most of them not old enough to drive.” He said that three young girls came over to offer support, but other youths reportedly taunted those keeping the vigil.

“Some people only feel powerful by putting other people down,” Smith said. “You can’t preach to them. It is hard to preach against hate.”

Ed Josey, 70, the president of the Staten Island chapter of the NAACP and an African American, said that the kids committing these crimes “are falling through the cracks.” He said when the crime in Port Richmond was just black-on-black, “there was not the police presence that you see now.” Still, this current wave of violence on Staten Island “is the worst that I can recall, but by and large people get along pretty well here. It’s a small element doing this.”

Josey was raised on the South Shore, had maybe three black classmates in high school “and never had a black teacher.” He said that the Staten Island Expressway was essentially a “Mason-Dixon line” on the island with few black people only allowed to the south of it. Today he says that the racial climate is far different. “There are far more interracial couples. The lines have fallen today. Progress has made things better.”

For more on civil rights related actions this summer, check out Action Taken on Bullying in Schools and No-Fault Divorce.

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 p.m.

The City's New Dollar Menu for Bus Riders

Photo (cc) 2010 Andrew Silverstein. Dollar van riders reach their destination in Jamaica

Eric Simit, a Jamaican immigrant, has been driving private commuter vans, most commonly known as "dollar vans," for 15 years in western Queens. He works six days a week -- from morning rush hour to the end of the evening commute, charging $2 a ride.

It's harder to make a profit lately, Simit says, as more vans hit the pavement. With little enforcement, many have found driving a “dollar van” an easy alternative to unemployment.

"It is the fastest way to make money fast," he said.

But Simit, other van drivers and their fast-cash business are becoming a more formal means of transport. In what Baruch College Professor E.S. Savas calls "privatization by default," Mayor Michael Bloomberg with the Taxi and Limousine Commission announced a yearlong pilot program in June, which allows vans to run on the discontinued B23, B71, B39, Q74 and Q79 routes. The target start date is Monday.

Faced with an $800 million deficit, Metropolitan Transportation Authority cut these five Brooklyn and Queens routes, along with several others, earlier this summer, because they were money pits. While the MTA could not break even on the routes despite large tax subsidies, immigrant entrepreneurs like Simit hope to operate vans along them and make a profit.

All five routes cost the authority over $4 per rider -- the Q79 was the highest at $8.08. The vans will charge $2 a ride. Vans save on expenses by escaping the high labor costs, American Disability Act requirements and environmental standards that face the transportation authority.

Supporters of the program, including Transportation Alternatives, see the private vans as the best, if not the only way, to serve city neighborhoods in a time of decreased resources and rising costs. But critics see a creeping privatization of transportation that means less service, lower wages and more pollution.

Privatizing Public Transportation

Dollar vans have a proven record of operating at the fraction of the cost of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. While less than 300 vans are licensed, thousands operate unauthorized across the city. Most vans illegally shadow city routes and undercut the authority's fare of $2.25, charging only $2.

The Taxi and Limousine Commission plans to have clearly marked vans that seat up to 20 passengers on the road by Monday. Currently, they are evaluating over 20 bids. For each route, prospective companies have outlined the frequency and hours of service, plus a list of stops. The commission will choose the companies which best serve the community, but riders should not expect the same service as the MTA.

“This is not a replacement of the MTA,” says an agency spokesperson.

If the program is successful, the administration plans to expand it.

Transit Workers United Local 100, the union representing many laid off bus workers, seeks to block the program. They have filed a lawsuit, claiming the commission has illegally created a “substitute transportation system” in “essence replicating the bus service” of the five routes. The union says they expect a ruling by the end of this week.

The TWU calls the pilot plan “a backdoor way to cut bus service.” (Ironically, the vans first emerged during the 1980 transit strike when West Indian immigrants began picking up stranded commuters in Brooklyn and Queens. After the strike, dollar vans remained, and again played roles in the MTA Strike and Green Bus strikes of 2005.)

A Taxi and Limousine Commission spokesperson claims the vans differ from the discontinued buses in that "drivers have specific stops but not a set route." Drivers can negotiate stops with passengers and change routes to avoid traffic. Taxi Commissioner David Yassky insists that the program is not a form of privatization. He says the agency’s “commitment to the MTA as the provider of public transportation is absolute.”

But suspicion by critics -- like the TWU -- that the plan is a form of deliberate privatization isn’t easily dismissed. The program was announced as Deputy Mayor Stephen Goldsmith takes his post at City Hall. Goldsmith, the former mayor of Indianapolis, briefly privatized public buses during his tenure. He is also chairman emeritus of the Manhattan Institute, a group that has promoted the competitive contracting of New York City transportation.

Despite the Taxi and Limousine Commission's claim that turning over bus routes to livery vans is just “to fill in the service gaps,” the idea far predates the recent cuts. A 1992 MTA report floated the idea of abandoning bus routes in favor of vans in some areas. Later Mayor Rudolph Giuliani pushed the City Council to loosen van restrictions. For Giuliani the vans were "American success stories" of immigrant entrepreneurs adding needed competition to the MTA.

But already the MTA had estimated vans reduced revenue on some routes by 15 percent. In response to so-called union pressure, the City Council limited the number of commuter van permits and placed heavy restrictions on pick ups -- citing the vans' reputation for aggressive driving and the vulnerability of MTA funding and jobs.

But where the City Council once saw a threat, they now see opportunity. Several council members including Speaker Christine Quinn support the pilot program.

Reductions in labor costs enable the dollar vans to keep running when city buses cannot. A 1995 report commissioned by the US Department of Transportation found that economic benefits are sacrificed if “labor costs are effectively locked in from one provider to the next.” This means the key for dollar vans to operate at a lower cost than the MTA is to pay workers less.

Despite that, many people are eager to drive the vans.

Getting Paid

At Jamaica Center, a large sign advertises the “Q5 van” and dollar van drivers load a steady stream of mostly Caribbean riders.

Gregory McDowell was one of them. He is the owner and sole driver for the one van company, Guymack. As he waited for his van to load on a 90-degree day, McDowell, his flowered patterned shirt half unbuttoned, explained the economics of running a dollar van: "$550 every two years for the permit from the TLC. … $9,000 to $10,000 a year for insurance," he said. (A customer interrupted him complaining of the heat. "I’ll open the back door,” he responded, not offering to turn on the AC.)

“Sometimes over a $100 a day for gas,” the 12-year driver continued.

McDowell works five days a week, driving about ten round trips a day mimicking the Q4 bus route. Sometimes the van is full. Sometimes it's less than half occupied. On his better days McDowell says he takes 160 passengers.

Drivers can make up to $40,000 a year, said another driver, Milton Brown. But those earnings are never guaranteed.

Alternatively, wages and ballooning pensions have often been a subject of criticism at the MTA (Former parks Commissioner Henry Stern opined recently that the MTA suffers fiscal problems because they are “incapable of containing their labor costs.").While MTA drivers earn more than $60,000 a year with generous benefits, little is known about van drivers' wages even amongst their biggest advocates.

Brown, a Q111 van driver, owns, maintains and fuels his van but works under a company. He paid his boss an initial fee of $2,000 plus $50 a week to use a van permit. If he didn’t have a van, he could rent one from the company for $550 a week. Brown says his earnings vary. During the school year he pockets over $500 a week without any benefits; during the summer he makes less.

At a Cost?

Sure the vans are cheaper -- both Brown and McDowell drive Ford Econolines, which cost them about $30,000, a fraction of the MTA’s hybrid-electric buses that go for over a half a million dollars.

But some say they come with an environmental and quality of life cost. For instance, MTA buses are environmentally and disability friendly.

While New York reverts back to the dollar vans, cities like Bogota to Jakarta have won praise for replacing fleets of informal private mini-buses with a system of eco-friendly public buses.

Now riders accustomed to hybrid buses will be picked up by less green, older vans. Mary Barber, a managing director at the Environmental Defense Fund, says they would prefer that the MTA buses remain fully funded, since “the more people you can carry on a vehicle with cleaner fuel, the better.” The TLC has not required vans to meet any special green standards or be handicap accessible.

In addition to reducing labor and capital costs, the dollar vans will also offer less service than the MTA. While city buses may run empty during off peak hours, few dollar vans operate late at night and in the middle of the day. “I prefer the rush hour in the morning and the evening. Midday is break time,” McDowell said.

Also dollar vans do not take unlimited metro cards, reduced fare cards or accept or give transfers. The MTA says only 14 percent of fares are the full $2.25. So while savings will be had by the city, many riders’ pockets will be hit harder.

Bloomberg dismissed such concerns at a press conference saying, “The issue here is not whether it’s more expensive or less expensive; it’s whether the service exists or not.”

UPDATE: The Wall Street Journal reports the TWU has won a bid to run vans on the B71 bus route. Still a judge is set to rule on the union's suit against the pilot program. Also the TLC has delayed the program's start date until September.

Andrew Silverstein is a freelance writer based in Queens.

The Price of Increased Surveillance

Photos by Andy Humm

One of the dozens of cameras -- government and private -- that keep watch on Times Square.

There are 82 police cameras and others cameras from stores trained on the streets in and around Times Square -- not to mention thousands in the hands of tourists -- but none of them seems to have picked up an image of Faisal Shahzad who is in custody for trying to set off a big homemade car bomb at the height of the theater rush May 1. The video most circulated by police of a suspect showed a white man changing his shirt on the sidewalk near the SUV packed with explosives. Lucky for him, a mob didn't find him and tear him limb from limb.

The bombing was averted that night due to conscientious community-minded vendors who contacted police as they often do when they spot something suspicious -- especially difficult in a district full of eccentricity. Shahzad was apprehended through good, old-fashioned police work -- tracking this bumbling would-be terrorist through identifiers on the vehicle that he had recently purchased.

Nevertheless, the early response of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, police and at least one editorial board to this incident was to call for more high-tech security. While most public officials seem to support that idea, a few critics have questioned the efficacy of such a system and the effects it would have on privacy and on our basic civil liberties.

Expanding the 'Ring'

New York is already in the process of blanketing the financial district with a "ring of steel" surveillance system modeled on London's. Now it wants to extend that to Times Square.

The system includes "cameras, sensors and analytical software," AFP reported, that, according to Police Commissioner Ray Kelly would trigger alarms when it "noticed an unattended bag or car circling a block too many times to be considered normal."

"Every public nook and cranny of midtown Manhattan should be covered by an integrated network of supersharp digital cameras that are monitored in real time,” the Daily News wrote in an editorial. "The only obstacle is money -- which actually should be no object given that lives are at stake." It will cost an estimated $110 million to expand the downtown system into Times Square.

Security vs. Freedom

Public officials are not oblivious to the concern about civil liberties. Speaking at a joint press conference in London with Mayor Boris Johnson shortly after the Times Square incident, Bloomberg said expanded surveillance "is controversial, but we have to make a balance between civil liberties and protection. We live in a very dangerous world."

Johnson, whose Underground system alone has 12,000 closed circuit TV cameras (to New York's 4,300, only half of which work), said, "Of course everybody understands the civil liberties arguments and the concerns, and they're very, very strong in this city and country, just as they are in New York."

Civil libertarian Bill Dobbs worries that the cameras are another sign that we are slowly giving up our basic rights. "All searching people does is get people used to the idea of being stopped and searched. We're getting to the point where when someone resists this, the public will wonder what they're hiding," he said.

Dobbs added, "Now, everything and everybody is under suspicion; some simply because of their race or religion suffer even more police and public scrutiny. ... We are continually pushed to give up cherished freedoms to fight an unseen enemy."

Sahid Buttar, executive director of the Bill of Rights Defense Committee, raised similar issues. "While surveillance is in some ways the antithesis of profiling (surveillance is broad and limitless, whereas profiling seems focused and targeted), both government practices offend the same constitutional principle of individualized suspicion inherent in the First and Fourth Amendments," he wrote.

Do They Work?

Dobbs also questions the effectiveness of the plan. "The [Metropolitan Transportation Authority] put up cameras in the 1980s but gave up on them because they couldn’t monitor them," he said. "Technology provides false hope."

In light of the various concerns, the expansion of the ring of steel needs more discussion and review, said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

"National security and warding off terrorism are enormously vital jobs and we all hope the police department is doing it well -- fantastically, in fact. To do it right, we have to not simply accept at face value every proposal put forward because it ought to work. The City Council and the mayor have to use the same high standards they put on other areas of government on the police department and its security effort," she said.

Philadelphia resident Ann Marie Carter, with her grandchildren, Nicole and Peter Godleski, said the police presence relieved her anxiety about being in Times Square.

While she acknowledges "cameras can be helpful," she said New Yorkers need to "demand more than just assertions that they will do the job," particularly in the current economic climate.

The proliferation of cameras and images is “creating a big haystack of information and we're looking for needles," Lieberman said. "We need to be strategic in our surveillance."

And she noted that, in the case of the attempted bombing in Times Square "it was the alertness and civic mindedness of ordinary people and police" that led to a resolution of the incident.

Fate of the Footage

So far, the administration has not said what it will do with the information and images it collects with its surveillance cameras. This bothers Lieberman.

She believes adequate safeguards do not currently exist to protect people against the improper use of their images. And she said that the "potential for abuse is more than imagined," starting with the potential for identity theft if the information is compromised.

Example of possible abuses abound. CBS News recently did an expose on how photocopy machines memory cards store tens of thousands of images of documents that are not wiped clean when the machine is sold secondhand. One of the machines in CBS's investigation had police records from Buffalo, another medical records from a hospital.

In an example closer to home, Kelly has said the police department plans to createthe city police maintain a searchable database of the hundreds of thousands of innocent New Yorkers -- mostly African American and Latino young men -- who are stopped and frisked every year. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn and Councilmember Peter Vallone, Jr., chair of the Public Safety Committee have written to Kelly expressing concern that such a retention of records would violate the spirit of the law mandating that criminal records be sealed. Quinn told me on May 17 that the council and police department staffs were in the process of setting up meetings about the matter.

The civil liberties union filed a class action lawsuit on May 19 to stop the police from keeping this database of innocent people. The police department has stopped and frisked 3 million people since 2004 and 575,000 just last year, a record. About 80 percent were African American and Latino.

Two of the plaintiffs tell their stories in a short film. Clive Lino, 30, an African American Harlem resident who works with special needs kids, was stopped "at least 13 times by NYPD officers between February 2008 and August 2009," but never was guilty of anything, the NYCLU said in a release. "They make me feel like a criminal or suspect when I haven’t done anything wrong," Lino said in the release.

"Innocent New Yorkers who are the victims of unjustified police stops should not suffer the further injustice of having their personal information shared indefinitely in a sprawling NYPD database” that may contain the names of more than 100,000 innocent New Yorkers, Lieberman said.

In general, Lieberman wants to require government to do "a privacy impact statement" when it seeks to expand surveillance. But trying to get information out of the government agencies that do this work -- from the New York Police Department to the FBI -- is "like trying to take blood from a stone," she said.

The police department did not respond to an e-mail request for comment on any of these issues. In the past, its spokespeople have deflected questions about security measures by citing security concerns. For this story, they would not answer questions about how many personnel will be needed to staff the expanded surveillance system, how long images will be kept, who will have access to them, and what evidence they have that these expensive methods are more effective than traditional police work.

Trusting the Police

Public officials I spoke with said they had few worries about the increased surveillance. Quinn said she was "confident" Kelly was conducting surveillance "in an appropriate way," despite her concerns about his retention of data on innocent people who have been stopped and frisked.

State Sen. Tom Duane said, "I'm 100 percent civil libertarian" and the trend to a surveillance society "makes me uncomfortable," but it "is important that we do everything we can to stay safer." While he said he did not oppose investing in reasonable security measures, he added, " People should also invest in groups like the NYCLU."

Gov. David Paterson, for one, does not think current efforts go far enough. "The cameras in use now don't emit strong enough images for identification," he told me, adding he wants a better system that can.

At the Crossroads of the World

Neither privacy concerns -- nor the attempted bombing that prompted the discussion -- seemed to be of much concern to the people filling Times Square on the beautiful Saturday evening of May 15. Two weeks after the failed bombing, Ann Marie Carter was sitting outside there with her two grandchildren, Nicole and Peter Godleski. She acknowledged being "a little leery" of visiting Times Square, "but I talked with my daughter who told me it would be covered more by cops. We feel safe."

Indeed, police and police cars were everywhere in Times Square that night, including many from the counterterrorism unit.

Many in Times Square wondered whether people on the streets might be more effective at finding problems than costly surveillance equipment.

"We spend all this money on anti-terrorism and it was a vet [one of the vendors] that saved the day," said Jason Esponiza, 19, of the Bronx.

Police security cameras don't bother actor Ryan Cavanaugh "I don't do anything that I'm ashamed of a camera seeing me do," he said.

Amadou Doye, who has been selling art in Times Square for 20 years, said he always watches out for suspicious things as do his fellow vendors who, he said, constitute a community.

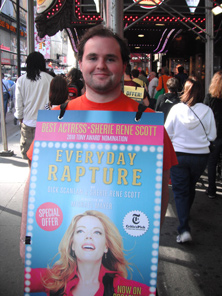

Vendors and people leafleting for shows and restaurants are a constant presence. Actor Ryan Cavanaugh, wearing a sandwich board for "Everyday Rapture," has been out there since winter. While he hasn't had to report anything to the police, he is more aware of the people selling illegal CDs on the street since an incident where one of them got involved in a gunfight some months ago.

But even those who question the cameras' effectiveness are not bothered by having them there. "I don't do anything that I'm ashamed of a camera seeing me do," Cavanaugh said.

"Certain things are necessary," Esponiza said, though he said this kind of surveillance might bother him more if it were taking place in his neighborhood.

Doye doesn't care how long the police hold on to the images they get . "If it is only for safety, they can keep them forever," he said.

Jason Faust, who leaflets for the long-running "Naked Boys Singing," said he was there the night of May 1. He saw the crowd gathering around the SUV and "didn't think much about it -- it's New York!" When the "pops" were heard coming from the vehicle, "the crowd started running, but I'm a New Yorker. I stopped."

He said that surveillance "has been around for years" and doesn't feel in infringes on his rights. While the cops were being a lot more watchful on this night, prior to the incident "half the time they were taking pictures of tourists" for them.

I tried to see if it would bother people to have a stranger they could see take their picture. It didn't. In Times Square where almost every tourist has a camera and police camera keep almost constant watch, no one seems to notice yet another camera -- or care.

The people who feel they just barely dodged mass death in Times Square are not thinking much about infringements of their civil liberties, but by not drawing a bright line somewhere, they may be forgoing rights they will never get back.

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 PM.

Council Approves Business Bill of Rights

Photo (cc) 2009 Light Snaffler

The City Council offered small businesses their own version of the first amendment yesterday by requiring every city inspector give shop owners a business bill of rights during city inspections.

The bill, approved unanimously by the council, is one part of Council Speaker Christine Quinn's agenda this year to snip away at red tape for the city's small businesses.

Bill of Rights

The (Intro 118) bill of rights will notify business owners of their right to consistent enforcement of agency rules and to appeal violations. It also will notify owners that inspectors must behave in a professional and courteous manner, be able to answer reasonable questions relating to the inspection and be knowledgeable on the city laws and regulations.

"By passing this legislation we will cut away at red tape that can often strangle small business in our city and will make the process of complying with city regulations more business and user friendly and much more accessible," said Quinn.

The city already has established a bill of rights for passengers of livery and yellow cabs. Council officials say putting a similar document in business owners' hands will assure they are protected from any unscrupulous city inspectors.

It may be no freedom of speech or religion, but the city's business leaders say the measure is a step in the right direction.

"It’s a great first step," said Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce President and Chief Executive Carl Hum. "Business owners are going to realize, 'I can contest this bill [from the city] and I can contest this violation, or I have the right to actually complain about an inspector.' It is a very empowering initiative."

Toxic Parks

After the parks department installed crumb rubber turf in an East Harlem park, leading to elevated lead levels, council officials said it was time to monitor what went into city playgrounds and fields.

So the council approved legislation (Intro 123) Wednesday to establish an advisory panel that will examine materials used in city parks and playgrounds. The panel will not have veto power over what materials the Department of Parks and Recreation can actually use, but will provide the agency with recommendations.

The eight-member panel, half appointed by the mayor and half from the speaker, will report to the department every six months. No new material can be installed without a review from the panel.

Saving a Church?

The council also voted to give landmark status to the West Park Presbyterian Church on the Upper West Side. The status was approved by a vote of 47 to 2, with council members Vincent Ignizio and Peter Koo voting no.

Leaders of the church, which is 116 years old and is an example of Romanesque Revival architecture, opposed the status, and had wanted to tear down part of the structure for development.

Ignizio said the city should defer to the property owner during landmarking disputes.

Affordable Housing Revision

The council unanimously approved a small revision (Intro 66) to its 421-a affordable housing program to allow developers to receive benefits faster.

Currently, a developer must file several different permits to prove construction has started and to trigger the receipt of tax exemptions. The revision would no longer force developers to show plumbing permits, which they argue are issued later in construction. The revision will affect projects as far back as January 2008.

Disabled Fear Cuts to Van Service Will Force Them to Stay Home

After work, Milagros Franco wheels home in her motorized chair across the 2½-mile pedestrian walkway of the Brooklyn Bridge and then waits for a bus to her Manhattan apartment. "It saves time," Franco said. But she depends on an Access-A-Ridevan to get to work every morning, again, because that too saves time.

Now, though Franco worries that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's proposed cuts to Access-A-Ride could triple the time it takes her to commute to her job at the Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled.

Access-A-Ride, the New York City Transit's service for people whose disabilities prevent them from using regular mass transit, now carries vans full of passengers door to door. Everyone is picked up at their home or office and then taken to their individual destinations. Under the service changes prepared by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, some passengers, instead of being taken directly to their destination, would be driven by the van to a bus, subway station or to another Access-A-Ride van.

The MTA also proposes to make access to Access-A-Ride dependent on weather conditions, so that service would change day-to-day and has proposed a number of other changes.

Spokespeople from disability groups charge that the cuts would add hours to a client's commute, making Access-A-Ride almost worthless. They say a trip that would take 15 minutes by a bus or subway now can last two hours on Access-A-Ride. The proposed service changes, they say, would add another two or three hours to the round trip, leaving many people with disabilities stuck in isolation in their homes.

The City Council will holding a public hearing on Access-A-Ride cuts on Tuesday at 1 p.m. at City Hall.

While some people with disabilities can and do use mass transit, approximately 20,000 people use Access-A-Ride every week. The program costs more than $451 million a year, and the MTA sees its proposed $40 million in cuts to Access-A -Ride as necessary to help alleviate the system-wide budget deficit of more than $750 million, according to Aaron Donovan, a spokesperson for the authority. The MTA has proposed an array of cuts including eliminating the free and reduced subway rides for students.

Metropolitan Transportation Authority chief Jay Walder has conceded that many of the reductions will be painful. "It's tearing my heart out right now," Walder said at a hearing earlier this month, "Last night at 1 o'clock in the morning I'm turning over in bed trying to figure out how to make the choices."

Longer Rides and Less Reliable Service

The MTA also has recommended applying more rigorous eligibility criteria for using Access-A-Ride, transferring more overnight service to taxis and other car services, making it more efficient and reducing personnel. The reduction in direct service, though, most alarms advocates.

Being driven to a bus or subway stop for part of the trip "would really discourage people with disabilities from going anywhere,” says Linda Ostreicher, director of public policy for the Center for the Independence of the Disabled, New York, a non-profit advocacy and support group. "Access-A-Ride is not able to keep a schedule, is not reliable now. Imagine waiting at home for an Access A Ride vehicle, getting dropped off at a bus stop, waiting for the bus, getting off the bus, and waiting for another Access-A Ride to get to your doctor's office on a day that you feel sick. Then imagine doing the whole thing again on the way home," Ostreicher said.

Evaluating every trip by weather conditions would be "time consuming and complicated," Ostreicher said. "It would require increased staffing, additional training and upgrading the current scheduling systems," and that, she believes, would wipe out any cost savings.

Advocates remain unclear how the transit authority would determine how weather conditions affect an individual's ability to travel on a given day. Many disabilities cause symptoms that vary from day to day, sometimes hour to hour. For example, some people with multiple sclerosis can experience heat intolerance that can cause decreased cognitive function, numbness, fatigue, blurred vision, tremor and weakness. For some people with cerebral palsy, cold can cause a tightening of extremities that makes it difficult to walk. Weather conditions like snow, ice and slush and rain create obvious problems for people in wheelchairs. Bad weather also makes it more difficult for people with low vision and blindness to navigate their path.

Franco said the cuts could affect her dramatically. Now, she takes a 7:45 a.m. Access-A-Ride van to her Brooklyn office, a 10 to 15 minute trip that gets her to her office one hour early.

The commute home is a completely different story. "Either Access-A-Ride doesn't show up, or they show up three hours later … or they may take a joy ride through the boroughs." Because the two wheelchair-accessible seats on the regular bus usually are already occupied by the time Franco would get on, she generally opts to wheel herself across the bridge.

"You gotta do what you gotta do to live," said Franco. She has had cerebral palsy since birth and has been wheeling across the bridge since attending Long Island University where she earned a bachelor's degree in social work.

On a bad weather day, though, she can't wheel. So she takes Access-A-Ride home on those days. "I can see that if I was subject to the service changes it would take so much time to get to and from work that I would not be able to keep my job. Both my clients and I would be stuck at home. I want to be an active participant in society. I want to help other disabled people," Franco said.

Fighting the Cuts

A numbers of local officials, including City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, council Transportation Committee chair James Vacca and other council members oppose many of the MTA's planned cuts. They say the reductions can be averted or reduced by reallocating federal stimulus funds and using capital money for operating costs.

"If these changes go into effect, the mass transit system would not be in compliance with the mandates of the Americans with Disabilities Act," Vacca said. The act makes it a violation of civil rights law for public transportation agencies, such as the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, to discriminate against people with disabilities in providing service. As part of that, the agency must make good faith efforts to operate accessible buses, subways and trains and, in cases where that would result in an "undue burden" to provide paratransit, such as Access-a-Ride.

Obstacles in the System

New York's transit system presents a number of barriers to people with disabilities. While the bus system is 100 percent wheelchair accessible, riders say there are not enough buses to meet demand. And subway and taxi service are not accessible for the majority of New York's disabled.

Service changes could also strand clients with other physical disabilities, infirmities due to age, those with cognitive disabilities that make it difficult for them to remember bus routes and directions, some people with certain psychiatric disabilities, and some people who are hearing-impaired.

Only 70 of some 470 subways station are accessible, according to James Weisman, counsel to the United Spinal Association, a disability rights and veterans service organization.

The others pose various obstacles. Some feature a six to eight-inch gap between the platform and the train. "For people with physical disabilities and the blind, the fear of being dragged by the train is an anxiety that deters its use," Ostreicher said.

Elevators frequently do not work. And for some trips, elevators exist on the downtown trip but not the uptown trip or vice versa. A broken elevator can present a disabled person with a major problem. Weisman explains, "If a passenger arrives at a station where the elevator is out of service, they have to travel to the next accessible station in the direction they don't want to go, go back and re-board a train in the opposite direction and come out on the other side of their original station."

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority says that its 110 accessible subway and commuter rail stations have, among other features, elevators or ramps, large-print and tactile-Braille signs, audio visual information systems, telephones at an accessible height with volume control, and text telephones.

With all city buses accessible to wheelchair users, the buses provide 100,000 trips to wheelchair bound people a month, according to Weisman. On the other hand, with only 300 New York City taxis at least partially accessible to wheelchair users, it is "a happy coincidence if one … happens to be accessible when you hail it," Weisman said. "And it is impossible to tell which ones are accessible."

Cabs and Buses for All

Access-A-Ride costs the MTA $66 a trip. The rider pays $2.25 each way. In light of that, some advocates believe the transportation authority and the city government should look for less expensive alternatives that would still give people with disabilities the mobility they need.< For example, Weisman notes, if buses were not accessible, the additional Access-A-Ride van trips would cost the authority an additional $79 million a year.

More accessible taxicabs could also reduce Access-A-Ride trips. The spinal association supports MV-1, billed as the world’s first mobility vehicle. With production slated to begin in October, the taxi meets the guidelines of the Americans with Disabilities Act, without requiring conversions or retrofits. It can accommodate even power wheelchairs and scooters and up to five other adults. Power wheelchairs will board the taxi by driving up the ramp. Manual chairs will be pushed in by the driver. The wheelchair using passenger sits next to the driver in the front seat which is empty space where a wheel chair can be secured.' It would operate by both dispatch and flagging and would be accessible to everyone. They will begin to be manufactured.

If a sufficient number of MV-1 taxis roamed city streets, paratransit riders could get a debit or credit swipe-card and pay $2.25 for a cab ride with the Access-A-Ride system making up the difference. The MTA would still come out ahead.

"Even the longest taxi rides are less than half the cost of paratransit rides," Weisman said.

State Assemblymember Micah Z. Kellner, Assembly member, proposed the swipe-card system back in 2009. He estimated then that it could save taxpayers $50 million a year in paratransit services – $10 million more than the Metropolitan Transportation Authority Says it must cut from the Access-A –Ride budget.

Data on Bullying Remains Scant, as City Touts Its Efforts

div> Mister Wiki at en.wikipedia

March 8 to 12 is Respect for All Week in the New York City public schools, a chance to intensify efforts around increasing respect for diversity in this incredibly diverse student population. The city, after a concerted effort by advocates, instituted the Respect for All program to combat bullying and has hailed it as a success. But critics say the system has not collected enough data to show whether the campaign has really managed to reduce what almost everyone agrees is a prevalent problem in the city schools.

In September 2008, the chancellor issued anti-bullying regulation A-832, which set up a procedure for filing, investigating and resolving "complaints of student-to-student bias-based harassment, intimidation, and/or bullying." The announcement, made with much fanfare, came after years of delays and the administration's adamant refusal to implement the Dignity in All Schools Act enacted by the City Council over the mayor's veto.

The administration continued to trumpet its achievements a year later. On the eve of the mayoral election in October, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, schools Chancellor Joel Klein and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn held a press conference hailing the "added mandated reporting and investigating guidelines" for the program. In a release, Bloomberg said, "We have set an example nationally in our efforts to combat intolerance and reduce bullying in our schools."

Dearth of Data

Critics, though, charge that the program was slow to get off the ground and that data simply does not exist to back up the administration's claims of success. Bloomberg likes to say that everything he does -- particularly when it comes to the schools -- is data-driven. However, when the anti-harassment program launched, the department did not collect any baseline data on the extent to which bullying was a problem. Since then qualitative data is not being collected on the impact of the regulation, and the numbers that do exist has been called into question.

The department did not issue a report on the results of the first year of the program, and even the second year of the regulation began in September 2009 without an analysis of the data on it.

Finally, in January 2010, the department released a brief "audit of bias-related harassment incidents" that reporting a total of 6,207 "bias-related incidents" in the 2008-09 school year among a total of 130,827 infractions of the Discipline Code. Of the bias-related incidents, gender accounted for 55 percent; race/color for 21 percent; gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation for 13 percent; ethnicity/national origin for 6 percent; religion/creed for 3 percent; and disability for 2 percent. The audit did not find out the extent to which students knew about and understood their rights under the new regulation.

In releasing the audit findings, Klein said in a statement that the "new data provides unprecedented information in helping us track and respond to bias-related incidents, and to prevent similar incidents from recurring." The release said the department this year charged principals with "creating rigorous anti-bullying plans" and that they will be held accountable for them in a school’s quarterly review.

Assuming the audit's figures are accurate, in a system of 1.1 million students and 1,600 schools, there were a little more than 6,000 bias-related infractions reported by about one half of 1 percent of students or an average of less than four per school.

This could be cause for great celebration. But the small number of students reporting bias harassment under the chancellor's regulation does not remotely approach the number of students who say in surveys that they are being victimized. As my colleague Ann Northrop, who spent four years in the schools in the late 1980s and early 1990s conducting trainings on gay and AIDS issues, said, "There are more like 6,000 incidents a minute."

The Department of Education's own Learning Environment Survey for 2006-07 found that 76 percent of city students in grades 6 through 12 reported seeing other students "threaten or bully other students at school" with 50 percent observing it "some of the time" and 29 percent more "all of the time."

Prevention and Detection

The program and the regulations include a number of measures aimed both at reducing bullying and ensuring that what bullying does exist is reported and addressed.

All students are supposed to have received a brochure about the program, many staff are supposed to have been trained on it, and a sign is supposed to be posted in every school on how to make a report.

Last June, the Department of Education reported that "two full days of training have been provided to approximately 1,800 teachers, counselors, and parent coordinators in schools serving students in grades six and above." Officials told Gotham Gazette they hope to have at least one staff member trained in every school by the next school year.

The data being collected around the Respect for All program does not try to determine how, or if, it has affected the level of harassment. In addition, critics charge the administration has not met all the requirements. In June 2009, at the end of the school year, advocates for the regulation complained that the department had fallen woefully short in terms of educating students about their rights to file a complain and that children still experienced high levels of bias-based harassment.

A coalition of groups, led by the Sikh Coalition, the Coalition for Asian American Children and Families, and the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, issued its own study and devastating report, "Bias-Based Harassment in the New York City Public Schools: A Report Card on the Department of Education’s Implementation of Chancellor's Regulation A-832." It gave grades ranging from C to F to the department on implementation of eight aspects of the regulation. The groups found that 54 percent of students were not aware of the regulation and 80 percent received no training on it. More than three quarters -- 76 percent -- were unaware that they could report harassment to an e-mail address. (They can, and here it is: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .)

Of students who did report harassment, 41 percent signed a statement that they were supposed to write and sign under the regulation, and 66 percent did not have their parents notified as required. What's more, 84 percent who of them did not get a written report from school officials on the results of the investigation as required.

Only 10 percent of cases involving bias-related harassment get "appropriate follow-up investigation and action," according to Sonny Singh, community organizer with the Sikh Coalition and a leader in the campaign to stop bullying in the schools, particularly of Sikh students who are often taunted for wearing their distinctive Patka head covering. "That means 90 percent of the time a student told a school official they have been harassed or bullied because of their race, sexual orientation, religion, etc. the school did not follow up the way it was supposed to," he said.

The coalition has criticized the data release in January as lacking "geographic specificity" at least by district. (The department has said it would consider this.) In addition, the coalition wants regular reporting mandated and is calling for "specific information about the discipline and intervention methods used in each case of harassment." It also wants a specific prohibition on bullying by teachers and other school staff, something school officials say is covered under other regulations.

Pauline Park, leader of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy, told the Gay City News that she faulted the program "for a lack of quality control."

The Department's Efforts

Elayna Konstan, chief executive officer of the department's Office of School and Youth Development, and Connie Cuttle, director of professional development, sat down with me to explain and defend the anti-bullying program. Konstan said "reporting is getting better" and that "amazing work" is going on in the schools around Respect for All.

Cuttle said that with the additional training and outreach, "kids are going to be more forthcoming we hope." She notes that middle school students in particular "are often embarrassed to say that they have a problem" with being bullied.

Since the majority of the incidents are based on gender, the department is testing a program, "Shifting Boundaries," in 50 schools. It aims to help young people understand what kind of language is appropriate in a boyfriend-girlfriend relationship and, school officials insisted, in a same-sex relationship though they would not share the curriculum, with me to show me how. The department also conducts a Relationship Abuse Prevention Program in 61 schools and a Safe Date program in 150 schools.

The Department of Education's partners in implementing Respect for All remain enthusiastic. Mark Weiss, education director of Operation Respect, said, "We are seeing deeper work being done in the schools as a result of the trainings." Eliza Bayard, executive director of the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network praised the department for "recognizing the importance of data to the on-going project of providing safe and effective learning environments."

In addition to the anti-bullying initiative, the Department of Education encourages students who are aware of imminent violence -- particularly but not limited to gun violence -- to anonymously call a national hotline, 1-866-SPEAKUP, to report it. Speak Up is run by a violence prevention program called PAX. Jamie McShane of Quinn’s office said that PAX will pilot a training program in 15 schools where principals have requested it to help young people understand that "snitching" in these situations is the right thing to do and can be done without fear of reprisal.

A Stubborn Problem

No one knows how many students bear the brunt of repetitive bullying. At an April 2008 lobby day for a state anti-bullying initiative, a high school student named Anthony talked about the ubiquity of bullying. He said bullying lead to drop out "every day" for fear of bullying. A student he knew took his life due to bullying. (You can see the video here.)

The regulation of September 2008 and Respect for All surely have some impact, but the Department of Education has not provided any data on what effect they have on school atmosphere, other than raw statistics on reports of incidents. And it can be difficult to assess even those figures. If those numbers go up this school year, it might not mean that bias-related harassment is worse, but perhaps that students are more willing to make complaints. That would represent a kind of success in that it might indicate that more students are aware of their rights. But all that will remain speculation unless the department begins to track the kinds of issues that advocates have.

Meanwhile the city's main tool in fighting bullying might well be that the public school system is so vast that those with the worst problems can be moved elsewhere in it. That is not the case in the upstate Mohawk Central School District where the http://www.nyclu.org New York Civil Liberties Union is settling a suit on behalf of a 14-year old student named Jacob. Over two years, according to a release from the group, Jacob "endured escalating harassment for his sexual orientation and for not conforming to masculine stereotypes. He suffered near-constant verbal assault, his personal property has been defaced and broken, and he was regularly pushed and had things thrown at him." He was also thrown down school stairs by another student and threatened with a knife by another. The boy's affidavit in the case is a harrowing read.

Because the district failed to investigate the incidents or discipline the perpetrators, the Civil Liberties Union sued in federal court and were joined by no less than the United States Department of Justice citing Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Department of Education has a Harvey Milk High School with a special mission toward gay and transgendered youth where it can place a student such as Jacob. That school, though, only has about 100 students. Most students facing harassment for reasons relating to sexual orientation attend mainstream schools where it is far from safe to be out or known as gay or transgender.

Thomas Krever, executive director of the Hetrick-Martin Institute for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth, which is home to the Harvey Milk School, said a year and half after the institution of the chancellor’s regulation in the schools, his agency's clients in mainstream schools "aren't feeling the effect yet." But he added, "Anything systemic is not going to be fixed overnight."

Krever hopes that Respect for All Week will heighten attention to the regulation and the problem of bullying, calling it a "good attempt" by the Department of Education for "creating safer environments."

Marisa Ragonese, director of Generation Q for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender young people in Queens, believes more needs to be done. She wrote in an e-mail, "While I always applaud any effort to make our schools a bit safer, the chancellor’s new regs, like the old ones, seem to be responding to this desire to appease a (gay, immigrant) special interest portion of the general population, and then continue with the real business of schooling." But, she went on, "homophobia and lack of respect for humanity is a big problem and needs to be approached as a public health issue." Addressing it, is "an integral component to our educational system, not an add-on or after thought."

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 PM.Brooklyn Community Splits Sharply Over Proposed Mosque

"Allah Akbar, Allah Akbar, Allah Akbar," yelled Mayor Ed Koch in Arabic on an exciting day for New York’s Muslim community in 1987. With his shout (which means "God is great") Koch was present to celebrate the construction of the first mosque in New York City built from the ground up -- the Islamic Cultural Center of New York on Riverside Drive.

Back then, the only significant obstacle to the mosque's creation were funding problems, changing plans and internal feuding, all of which were eventually resolved.

Much, though, has changed in the past two decades. Now challenges to new mosques in New York City have grown to include some fresh problems, as the proponents of a new mosque in Sheepshead Bay have learned.

The proposed mosque, which does not yet have a name, has received the criticism that faces any establishment that tries to plant itself in a residential neighborhood: worries about parking problems, noise and the effect on property values. In the diverse waterfront Brooklyn community, the proposal to build a mosque also has become ensnared in allegations of bigotry on both sides, concerns about terrorism and debates about the Middle East. While the dispute there is the most heated in the city so far, it comes at a time when some other mosques in the metropolitan area have received increased scrutiny.

Creating Mosques

There are over 140 mosques in New York City alone, and since Sept. 2001, attitudes toward mosque building in New York City and Long Island have been mixed. In 2008, Temple Israel of Jamaica, then located in Holliswood, Queens, peacefully became the Bait-Uz-Zafar mosque. Due to a decrease in the number of conservative and reform Jewish congregations, the synagogue shifted hands with local Muslims of the Ahmadiyya sect to accommodate their growing numbers. Clergy members from several religious groups along with local politicians held a ceremony to mark the transformation from Jewish temple to Muslim mosque.

The Long Island Muslim Society, located in the quiet, suburban town of East Meadow, was at the center of attention in 2002 when it wanted to convert two homes that it used as its headquarters into a traditional mosque and school. The construction plans drew protests from some residents who complained about increased traffic and parking problems. The mosque received a permit to build the structure in 2007 after a long struggle.

The Parkchester Jame Masjidin 2009 became the first mosque in the Bronx to ask permission to use electronic amplification to perform the Muslim call to prayer, the "adhan." The adhan, which lasts for less than two minutes, is supposed to sound five times a day to call worshippers to pray, but mosque officials agreed to request permission to air the adhan only four times a day, skipping the early morning call. The mosque rescinded its request for the permit back in November when mosque leaders flew to Mecca to make the hajj pilgrimage but are once again seeking permission for its use.

The Cordoba Institute has purchased an abandoned building two blocks away from Ground Zero and plans to turn it into an Islamic center. Formerly leased to the Burlington Coat Factory, the building now used to accommodate the overflow of worshippers from Al-Farah mosque in Tribeca,. According to an articlein the New York Times, Mayor Bloomberg’s spokesperson Andrew Brent has said, "If it's legal, the building owners have a right to do what they want."

Not everyone agrees. Some opponents of the mosque have started a website called No Mosques at Ground Zero. It demands that Bloomberg "honor those murdered on Sept. 11, 2001 by not permitting a mosque to be built on Ground Zero." The creators of the website did not answer requests to be interviewed for this story.

Some elected officials are not shy about expressing their own negative views of Muslims and mosques. In 2007, Republican Rep. Peter King of Long Island said in an interview with Politico.com, "We have, unfortunately, too many mosques in this country. I'm aware of ones in New York. To me, they certainly raise suspicion, they should be looked at carefully." On another occasion, he referred to Muslims as "an enemy living amongst us."

And Koch, who appeared to have given his blessings for the construction of the Islamic Cultural Center 23 years ago, recently said on Neil Cavuto's show on Fox News that "hundreds of millions of Muslims are terrorists."

A Divided Community

New York City is home to over 600,000 Muslims, according to a study by Columbia University. The Association of Religion Data Archives found, that, as of the year 2000, there were nearly 58,000 Muslims living in Brooklyn, many of whom live in Bay Ridge, Coney Island and near the western part of Atlantic Avenue. There are over 28 mosques in Brooklyn alone.

The vacant lot on 2812 Voorhies Ave, has been purchased by Allowey Ahmed, a Yemeni-American who has lived in Brooklyn for over 40 years, in partnership, with the Muslim American Society. The new mosque will be four stories high and will house a community center as well as classrooms.

When Ahmed submitted plans for the mosque’s construction to the Department of Buildings in July 2009, it called for a minaret. His proposal was rejected but he submitted a second plan, and is now proceeding with construction of the mosque without the minaret. In an article on Sheepsheadbites.com, Ken Lazar, the Department of Building's community affairs liaison, said that religious institutions may build "as of right" so long as they fit in with zoning regulations.

The Muslim American Society has accused some residents of bigotry against Muslims.

A group called The Bay People has distributed leaflets urging people to "Say NO to mosque at 2812 Voorhies Avenue." A petition against the mosque's construction has made its way onto the Internet. The petition charges that the Muslim American Society has associations with organizations and individuals that espouse anti-Semitic views, and that it supports terrorist groups, encourages suicide bombings and rejects Israel’s right to exist. So far, 293 people have signed the petition.

In particular, critics have targeted Mahdi Bray, executive director of the Muslim American Society's Freedom Foundation and an outspoken critic of Israeli policies.

The Muslim American Society denies it has ties to terrorists or anti-Semites. Theresa Scavo, chair of Community Board 15, has called the creators of the flier ignorant people who understand neither the spirit nor the letter of American law guaranteeing freedom of religion.

At a January civic association meeting, Scavo reportedly saidthat those opposed to the mosque might have a better chance if they stuck to issues such as parking and traffic. "If you want to succeed, do not use the word mosque. Do not use the word Muslim. Request the traffic reports. Go take photos of the double parking at the other mosques during calls to prayer. Have [the opponent] done that? No. Because they’re lazy. You can’t just go with your mouth. You need paper,” she said.

The City Councilmember from the area , Lewis Fidler, has defended the mosque, saying "To make a decision that because this is a mosque and for no other reason that this will be a haven for hate or terror is over the top."

Neighbor vs. Neighbor

At a recent Community Board meeting, Sheepshead Bay residents -- including some who support the mosque and others who oppose it -- packed a large room at Kingsborough Community College. Though discussion of the mosque was not on the meeting’s agenda, the board allowed concerned residents to speak.

One Muslim man said at the community board meeting that the Muslims of Sheepshead Bay do not have a place of worship within walking distance and thus have to travel to worship. "I am sorry to hear what our neighbors are saying, it really hurt. We would like to worship God the same way like everyone else does, according to their own concept of God. This should not be too much to ask in these United States of America."

A resident named Stephanie who called herself a “Sweda-Rican” spoke against the mosque, eliciting several rounds of applause from the audience. "What troubled me most about this was portraying people who don’t think this mosque is a good idea as racist. I am not a racist."

"We have a good reason for our concern. It is simply rational fear. We must be honest," the woman said.

Mohammed Razvi, a Pakistani who founded of the Council of Peoples Organization and is co-founder of the We Are All Brooklyn coalition, urged all residents of the neighborhood to unite. "We should all come together to address those concerns. It's everyone's community," he said to the crowd calmly. "Brooklyn is an example of how peace can be achieved throughout the state, throughout the world. Please uphold that"

Fear Factor?

"My neighborhood will die," complains Greg Kalman in a thick Russian accent.

Kalman represents The Bay People. He said he is concerned about a decrease in parking in the area and thinks that property values will drop because if the mosque opens and result in an exodus of homeowners out of Sheepshead Bay.

In a telephone interview, Kalman said that he was frightened that tenets of radical Islam will be taught in the mosque. Kalman, who is Jewish, immigrated to the United States from Azerbaijan, a Muslim country in Central Asia carved out of the Soviet Union. Though he says he never had any problems with his Muslim neighbors in his home country or in Sheepshead Bay, he is still wary. "I put a menorah on my window during Hanukkah," he said. "I don't know if someone will come in and break my window."

"I am not a racist," he insisted. "I don’t think that the majority of Muslims are radicalized, but there is the possibility that a small percentage can become radicalized. People are afraid."

He also accused the Muslim community of Sheepshead Bay of being too insular. "I talk to the Italians, the Russians, but the Muslims don’t talk to anybody," he said.

To bolster his charge that the mosque backs the Palestinian group Hamas, Kalman cites a 2000 video of Mahdi Bray attending a demonstration in Lafayette Park in Washington D.C. In the clip, Bray nods and raises his hand as the speaker asks the audience whether anyone is a supporter of Hamas, which governs Gaza. The U.S. government classifies Hamas as a terrorist organization, but some nations, including the United Kingdom and Australia, only consider Hamas' military wing as a terrorist organization.

An outspoken critic of American foreign policy in the Middle East, Bray denies that he harbors any prejudice against Jews and said his work with interfaith organizations is testament to this, "I reject the idea that criticism of Israel makes you an anti-Semite," he said.

Bray also disputes a statement on the online petition saying that the Muslim American Society "has a troubling history of associations with radical organizations and individuals that promote terrorism." He said that the society has developed youth programs to steer youngsters away from the path of religious radicalism.

While Bray urged mosque officials to try to address all the concerns of the community and accommodate their needs, he thinks that complaints about parking, noise and property values are "pretexts" for simply not wanting a mosque. "Those are not the major issues," he said.

An online petition in favor of the proposed mosque has made its appearance on the Internet as well. That petition has so far gathered 583 signatures of support.

"We are the new kids on the block," Bray said of Muslim Americans. "We are going to build this mosque and we don't have to apologize for anything. Let the bigots scream."

Haitian's Case Focuses Attention on Deportations

The campaign to free community activist Jean Montrevil, a native of Haiti, began on Dec. 30, 2009, the day he was taken into Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody during a routine check in and placed in the York County Prison in Pennsylvania. His detention sparked outrage among his supporters, resulting in the arrest of 19 people at a rally held to show solidarity with Montrevil and to protest what they deem are unfair immigration practices.

"These immigration laws destroy families and contradict the values we should uphold as a society," said Reverend Donna Schaper of Judson Memorial Church where Montrevil’s family worships. Schaper was among the 19 arrested. Montrevil's plight also caught the attention of several local politicians including U.S. Reps. Jerrold Nadler and Nydia Velasquez.

For now, though, Montrevil is free. On Jan. 23, after the government decided to halt all deportations to Haiti because of the earthquake there, he was released from the detention center.

His reprieve may be only temporary. And meanwhile, thousands of other immigrants still face deportation. As a result of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act signed in 1996 by President Bill Clinton, many immigrants have either been deported or face the threat of deportation. The act, which was retroactive, added a number of new crimes to the list of deportable offenses, which originally included only serious crimes such as murder and drug trafficking.

A Rise in Deportations

From Oct. 1, 2008 through June 30, 2009, ICE deported or returned more than 271,200 aliens, a more than 18 percent increase than that of the same time period in the previous year. In 2008, ICE issued 168,800 charging documents to formally begin proceedings to remove criminal aliens from the United States.

Immigration advocates have protested these actions, arguing that deporting someone who has already been punished with imprisonment is unfair, particularly when the person has turned his or her life around. Angad Bhalla, an organizer with the New Sanctuary Coalition, which opposes deportations, echoed the sentiments expressed by many supporting Montrevil and others facing deportation: "He served his time. He has reformed himself. Our priorities are out of whack if we feel that those are the people to deport."

"Jean put a face on this issue," said Bhalla, who has known Montrevil for three years. He praised Montrevil for sharing his story with the public. "For some, the only chance for people to stay with their families is to hide," he said. "It’s rare that people will talk about what they’re going through."

Bhalla is particularly critical of the effect immigration laws have on children. "What gain is there in making orphans out of children and breaking up families?" he asked.

In a letter written before his release, Montrevil said that he saw his children's future as "bleak and very fragile." "We make promises to be there for them, to protect them and cherish them, I may not be able to do that for my babies," he said.

Supporters of the laws, though, say the country needs to control who can stay here. " There are more people that want to come here than there are openings," said Bob Dane of the Federation for American Immigration Reform. "You got to keep your nose clean if you want to stay here."

As for Montrevil, Dane said, "He tossed his chance away. … He used a slot that someone else could have used and what did he do? He spent his time in jail."

John Vinson of the American Immigration Control Foundation said that, while Montrevil might have deserved his reprieve, the deportation procedures are necessary. "We can show compassion in some cases, but if we don't enforce the law for the most part, we're courting chaos," Vinson said.

A Costly Mistake

Montrevil's problems date back to a fateful decision made over 20 years ago. Montrevil, who legally arrived in Brooklyn as a teenager in 1986, was arrested for selling cocaine, an aggravated felony, in Virginia in 1989 and served 11 years in. While Montrevil was incarcerated, the Immigration and Naturalization Service initiated deportation proceedings against him, and in 1994, he was ordered deported.