Proposals Target Closure of Gender Pay Gap

photo: @PowherNY

During a recent panel conversation at The New School, only two people in a crowd of about 50 raised their hands when the audience was asked if they were confident there is no gender pay gap in their workplace. The panel, called “Getting Even,” was organized by the Center for New York City Affairs to discuss the causes of the pay gap between men and women and the steps New York City can take to close it.

“When men go into traditionally female occupations, they get paid more. So gender is the only differentiator here,” said moderator Teresa Tritch, a member of the New York Times editorial board. “Male nurses get paid more than female nurses, male flight attendants get paid more than female flight attendants. It’s across occupations, it’s across ages, it’s across educational level.”

While many women receive lesser salaries in the same jobs as men, leading to calls for “equal pay for equal work,” the wage gap is also caused by devaluing so-called “women’s work,” the trend that keeps women in traditionally lower-paying jobs. Pay inequity has been a persistent problem in New York City, where women make up almost half of the workforce. Across sectors and jobs, a woman who works full-time in the city earns 87 cents to every dollar a man makes, according to a recently-released study by Public Advocate Letitia James, published in April. This means on average, a man in New York City makes almost $7,000 more than a woman every year.

The study also found that women working for the city government experience a pay gap that is three times larger than women in the private for-profit sector and 2.5 times larger than women in the private nonprofit sector.

Public Advocate James began looking into the gender wage gap after Local 1180 CWA, a labor union representing mostly public sector workers and some employees from private companies or nonprofit organizations, brought a lawsuit against the city under the administration of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, claiming that administrative managers were being underpaid. At the time of the lawsuit, more than 78 percent of administrative managers in the city were women. But as women became that significant majority in these management positions, the minimum salary fell. Even women who worked for the city for 20 to 30 years made about $7,000 less each year than men with the same experience, according to a CWA statement on the case. The lawsuit was settled by the Bloomberg administration, but James continued her research and found more information on the municipal gender pay gap.

One of the driving factors in the municipal pay gap is the jobs that women typically hold in the public sector. In New York City’s municipal workforce, about 93 percent of employees are unionized, so both men and women are often locked into certain pay scales through collective bargaining.

According to the public advocate’s study, the Department of Education and the Administration for Child Services have the highest percentages of female employees. These agencies have average salaries of $69,901 and $49,606, respectively. Women also make up 70 percent of employees in the Human Resources Administration, which has an average salary of $41,401. Men represent the largest percentage of employees in uniformed workforces, like the Fire Department and the Department of Sanitation, which offer average salaries of $76,488 and $69,339, respectively. The data suggests that women are concentrated in city jobs that traditionally have lower incomes than the jobs that men dominate. Policies like work hours, promotion practices, and civil servant exams also contribute to the wage gap, which the study says should be monitored more closely as part of the effort to close the gap.

“In order to correct this, we need to correct it first at home,” James told Gotham Gazette in a phone interview, referring to the gender pay gap generally and among city employees more specifically. “We have the ability, given our oversight and our legislative authority, to correct that which we have control over. We should start in-house first.”

The public advocate’s study includes a list of recommended actions to close the municipal wage gap. An Equitable Pay and Opportunity Task Force - made up of city officials, researchers, and political scientists - will be created by the Public Advocate’s office to provide research-based recommendations to Mayor Bill de Blasio and the City Council. This task force will be separate from the mayor’s Commission on Gender Equity and will examine different data and industries, but James has reached out to the mayor’s office with plans to collaborate and is waiting for a response, she said.

Two essential steps to closing the public sector gap, according to James, are disclosing wage information about the public pay scale and preventing inquiries regarding salary history during hiring processes.

“When you talk about previous wage salary, you establish a floor,” said James. “And as a result of that floor, which is discriminatory in nature, you start off with a discriminatory base. So we really want to prohibit city agencies from asking about previous salary information of job applicants.”

City Council Member Ben Kallos, the only man who serves on the Council’s Committee on Women’s Issues, also believes wage disclosure will be an important tool in working towards pay equity.

“You can look up every public employee’s salary and we know what their gender is,” Kallos told Gotham Gazette in a phone interview. “Why can’t we do an automatic and internal audit comparing folks to their collective bargaining and make sure people are getting paid what they’re supposed to? The entire point of the civil service is supposed to be equity and treating people based on what they know, not who they know or what their gender is.”

While the public advocate’s study notes that wage disclosure and the prevention of job application questions regarding previous salary can be encouraged in the private sector, it cannot be mandated that private industries follow these practices. However, wage disclosure could be just as important for the public sector, according to “Getting Even” panelist Beverly Cooper Neufeld, the founder of advocacy group PowHer New York. At the New School event, Neufeld noted wage transparency is necessary for identifying wage gaps, holding employers accountable, and discouraging them from discrimination.

Other solutions offered by the panelists included strongly enforcing anti-discrimination laws, advocating for the right to collective bargaining and a higher minimum wage, support for government programs like universal preschool, laws for paid sick leave and paid family leave, and changing the culture of workplaces.

Some of these potential solutions have already been enacted, such as New York City’s Pre-K For All program, which helps mothers work at all or stay at work longer by providing free child care (though that is not the sole or even top purpose of pre-K, of course). The state also passed a paid family leave policy as part of the 2016-17 state budget and set a path toward a minimum wage of $15 per hour.

Commission on Gender Equity Director Azadeh Khalili, also on the wage gap panel at The New School, said New York City will look to best practices from other cities. She cited a mentor program in Boston as an example, which provides about 80,000 women training in negotiating for themselves.

On changing workplace culture, Neufeld discussed the perception of motherhood in the workplace as a significant factor in the pay gap. She referred to the unofficial “bonus” men receive when they become fathers: they are more valuable to the workforce because they are now working to provide for a family. Women, on the other hand, are devalued when they become mothers because it’s assumed they will spend less time at work and more time with their children. On average, women lose about 4 percent of their earnings every time they have a child, according to a 2014 study by Michelle J. Budig, a professor at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

However, the gender wage gap affects women regardless of parenthood, education level, or occupation.

Women also face inequity as consumers, according to a study on gender pricing published last year by the city’s Department of Consumer Affairs. The results showed women’s products cost about 7 percent more than men’s, costing women an additional $1,351 every year, on average. The price difference in products marketed to women - ones identical to men’s products aside from packaging or coloring - is most significant in personal care items, children’s toys, and clothing (for both girls and women), according to the DCA study.

“Our study showed that no matter whether you’re a baby or a senior citizen, you’re still being affected,” DCA Deputy Commissioner Alba Pico said in a phone interview. “You’re paying more than what a male would pay for your whole life.”

The gender wage gap and gender pricing are often considered “women’s issues.” But as more women enter the workforce and become the primary providers for their families, they become economic development issues.

“There are a lot of women in the city of New York who are heads of households,” said Public Advocate James. “And when you cheat them out of an equitable and fair wage, you obviously have an adverse effect on their children and on the local economy.”

***

by Carmen Russo, Gotham Gazette

@carmenjrusso @GothamGazette

Several Council Asks Remain as City Budget Negotiations Hit Home Stretch

The Mayor and Council discuss the budget (all photos: William Alatriste)

City budget season entered its home stretch last week when the City Council conducted its final hearing on Mayor Bill de Blasio’s $82.2 billion executive budget for fiscal year 2017. With a deal between the Council and the mayor due by the July 1 start of the new fiscal year, the parties will largely negotiate behind closed doors, with funding levels for a number of major priorities on the table. There are also lingering questions about savings and how much the de Blasio administration is asking its agencies to trim as spending grows.

On the Council side, negotiations will be led by Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and Council Member Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, chair of the finance committee. This past Tuesday, Ferreras-Copeland reiterated concerns she had expressed at the first executive budget hearing that de Blasio’s latest spending plan, his executive budget, largely ignored the Council’s priorities while adding massive appropriations for the administration’s proposals.

“I can say today, after presiding over nearly 65 hours of Executive Budget hearings, that the testimony we heard from the agencies only reinforced this notion,” she said in her opening statement at the final executive budget hearing. “Over the past two weeks, we questioned each commissioner about the items from the Council’s budget response that were not included and were repeatedly told that they were just not a priority.”

Ferreras-Copeland called out agencies for assuming that the Council would fill budget gaps with its discretionary funding - particularly for the Department for the Aging and the Department of Youth and Community Development - and also pointed out that they had given few details about how $2 billion in new funding would be implemented. Throughout the budget process, she said, “the Council’s ability to fulfill its Charter-mandated review and oversight role was hindered by the administration’s delay in providing vital information, despite public assurances that documents and data would be provided promptly.”

Specifically citing the administration’s ambitious plan to overhaul the municipal hospitals system, New York City Health + Hospitals, as problematic, Ferreras-Copeland (pictured) said that the plan was provided to the Council less than a day before the first executive budget hearing.

The issue of savings, which has underscored the entire budget process, was raised again last week. The mayor’s executive budget shows $5.4 billion in savings through the Citywide Savings Program through Fiscal 2020. For 2017, however, Ferreras-Copeland stressed that the city’s reserves are largely flat, and Council Member Helen Rosenthal pointed out later that the CSP depends heavily on debt refinancing, spending re-estimates and accruals (delays in spending from earlier years) rather than programmatic efficiencies.

The issue of savings, which has underscored the entire budget process, was raised again last week. The mayor’s executive budget shows $5.4 billion in savings through the Citywide Savings Program through Fiscal 2020. For 2017, however, Ferreras-Copeland stressed that the city’s reserves are largely flat, and Council Member Helen Rosenthal pointed out later that the CSP depends heavily on debt refinancing, spending re-estimates and accruals (delays in spending from earlier years) rather than programmatic efficiencies.

An analysis by Citizens Budget Commission, the nonpartisan nonprofit budget watchdog, showed that $189 million of the nearly $1 billion in savings proposed just for fiscal 2017 comes from agency efficiencies. “The increased size of the CSP is a step in the right direction,” says the report, “but too little of the savings are from agencies thinking strategically and creatively about how to provide value to taxpayers and do more with less.”

Since coming into office, de Blasio has on one hand been praised for what he is socking away and the general health of the city economy and his fiscal prudence, but on the other hand he’s been criticized for not demanding more in savings from his commissioners and not having the recommended budget “cushion” in savings. Under de Blasio, savings have grown, but as the city economy has boomed, union contracts have been settled, and the mayor has implemented many new programs, spending has grown rapidly and the cushion does not meet the percentage of city spending that watchdogs like city Comptroller Scott Stringer say is wise.

At a press conference on Wednesday, Speaker Mark-Viverito said Council members would start discussions on the negotiations by Thursday. “We’re starting to have the formal process internally to delineate the priorities and engage with the administration,” she said in response to a question from Gotham Gazette. She pointed out that many of the Council’s top priorities had already been identified over the course of budget hearings.

Council members have publicly called on the mayor to increase funding for a variety of initiatives and programs including summer jobs for youth, emergency food assistance, cultural institutions, human services nonprofits, seniors, and the offices of the five district attorneys.

Summer Youth Employment

Council members and community advocates have been pushing for increased baseline funding for the Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP), which provides six weeks of paid work to youth 14 to 24 years old. Last year, the program served 54,000 young people and supporters want to increase that to 60,000 this year, reaching their eventual goal of 100,000 by the 2019 fiscal year. Currently, the city is allocating $36.5 million for SYEP which, along with $15.6 million from the state, would fund about 35,000 jobs.

At last week’s final executive budget hearing, Dean Fuleihan, director of the Office of Management and Budget, stressed that the administration has made huge commitments to DYCD, increasing the agency budget by nearly $250 million over the years, but the SYEP was not a priority. “I understand that the Council wants this to be a priority and that’s going to be a part of our conversation,” Fuleihan (pictured) said.

At last week’s final executive budget hearing, Dean Fuleihan, director of the Office of Management and Budget, stressed that the administration has made huge commitments to DYCD, increasing the agency budget by nearly $250 million over the years, but the SYEP was not a priority. “I understand that the Council wants this to be a priority and that’s going to be a part of our conversation,” Fuleihan (pictured) said.

Emergency Food Assistance

The executive budget includes $8.2 million for the Emergency Food Assistance Program (EFAP), but 48 Council members signed a letter calling on the mayor to increase this to $22 million and baseline it in the budget. “Millions of New Yorkers rely on meals from food banks and soup kitchens, and the need is greater than ever before,” said Council Member Stephen Levin, chair of the general welfare committee, in a statement last week. “No family should have to choose between paying for necessary expenses and being able to eat,” he added.

Fuleihan pointed out that this increased need was due to significant cuts in federal funding for emergency food programs and that the administration was open to discussing the funding with the Council.

Cultural Programs

A number of Council members are pushing to increase the budget for the Department of Cultural Affairs. Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer, chair of the cultural affairs committee, pointed out at last week’s hearing that the City Council’s cultural initiatives have increased over the last two years but the administration is not sharing that commitment. He and many of his colleagues want the city to increase funding for nonprofit cultural institutions by $40 million - it has remained flat for the last three budgets - and to baseline $43 million for six-day service at city libraries. Currently the city has baselined about half of that library funding. Again, Fuleihan promised to work with the Council on the issue.

Department for the Aging

Council Member Margaret Chin said that the previous administration “was all about cuts” to funding for seniors and the Council expects this administration to be “quicker and faster” in funding services for a growing senior population.

In his testimony, Fuleihan emphasized that the administration has committed to senior services and increased Department for the Aging’s budget by $30 million since Mayor de Blasio took office, reversing a trend of at least ten years of reductions in DFTA’s budget. He insisted to Chin that the administration has increased DFTA case manager salaries and that it would eliminate waiting lists for homecare, one of Chin’s priorities.

District Attorney Offices

The executive budget did not include any additional funding that the five District Attorney offices had requested after the preliminary budget was released. The Council, which listed public safety as one of its top priorities in its budget response, called on the mayor to heed these requests, which total about $21 million. Citing the Council’s own commitment to criminal justice reform, including the funding of 1,300 new officers for the NYPD last year, Council Member Vanessa Gibson, chair of the public safety committee, said, “What I fail to understand is, in the executive, is why we have a big whopping zero for the district attorneys.”

Fuleihan said the dialogue with the district attorneys was ongoing, particularly the two new DAs in the Bronx and Staten Island. “We do believe that’s part of the adopted budget,” he said at last Tuesday’s hearing.

Human Services Nonprofits

On Thursday morning, Council members rallied with nonprofit groups at City Hall to push the mayor for $25 million to cover administrative costs at contracted nonprofits that provide social services. These nonprofits, according to a report by the Human Services Council, are facing a budget crisis owing to government underfunding. In a letter, 47 Council members asked the mayor “to offer some critical budget relief” to nonprofits and help them invest in equipment, technology, and staff development.

In a statement on Thursday, mayoral spokesperson Karen Hinton said, “We look forward to working with the Council throughout the budget process.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Push Continues for Budget Boost to City Contracted Nonprofits

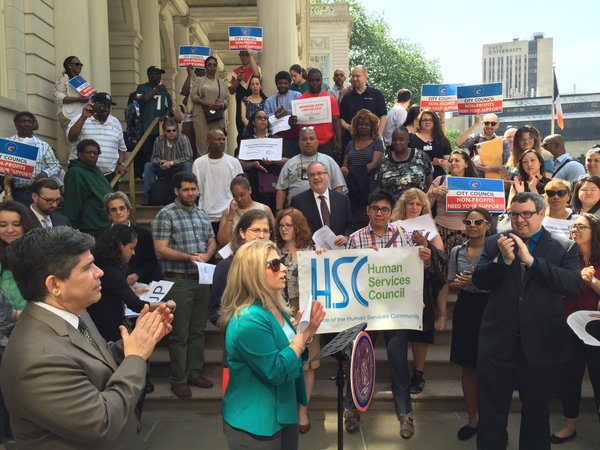

The Human Services Council and City Council Members rally at City Hall

On a hot and sunny day, dozens of nonprofit workers took to the steps of City Hall to call on Mayor Bill de Blasio to fund a 2.5 percent increase for the administrative costs of nonprofits that contract with the city. Forty-seven of 51 City Council members have signed on to a letter to de Blasio asking him to baseline the increase, an additional $25 million annually, into the budget as the city moves toward adopting a new spending plan. A budget deal between de Blasio and the Council is due by the start of the new fiscal year on July 1.

As nonprofits and their employees have strained under increasing costs for space, staff, and programming, sector leaders, workers, and legislators are pointing to what they say are flaws in how the city budgets funding for vital services.

The human services nonprofits requesting more funding from the city provide a wide range of services to the city’s most vulnerable, including foster care, homelessness services, mental health care, immigrant services, early childhood literacy and after-school programs, home-care for the elderly, and more.

The city is required to provide many of these support services, but contracts them out to nonprofits to save money and increase efficiency. However, many of these nonprofits are on the brink of insolvency and are borrowing from banks to meet payroll and provide services due in part to decades of underfunding from federal, state, and city government.

“I’ve had to make some really hard decisions in this past year,” said Marla Simpson, executive director of Brooklyn Community Services. “I can think of two programs that are very well run and much needed in our communities where we have had to choose to not fill vacant positions because we cannot afford to put the staff in that position and also pay the rent or the insurance bill.”

The increase in “other than personnel funding” that nearly the entire City Council and a coalition of human services nonprofits - including the Human Services Council, the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies, the New York Immigration Coalition, Urban Pathways, and the Center Against Domestic Violence - are asking for would help city contracted nonprofits to afford staff development, rent, repairs, equipment, and technology. (City Council Members who did not sign the letter to de Blasio were Finance Chair Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, Dan Garodnick and David Greenfield)

These nonprofits are “consistently paid 80 cents for every dollar of work,” said chair of the Contracts Committee Helen Rosenthal, who spearheaded the letter to the mayor, referring to the fact that although government contracts account for the majority of nonprofits’ budgets, they pay roughly 80 cents or less of each dollar of true program delivery costs. “Human services providers need funding…in order to effectively serve the at least 2.5 million New Yorkers in their care,” Rosenthal added.

The de Blasio administration has taken steps to improve conditions for workers in the human services nonprofit sector, which employs over 200,000 New Yorkers, a majority of whom are women (four out of every five workers). In May of last year, de Blasio included a 2.5 percent cost of living adjustment increase for some of the city’s human services providers, and this January, announced a $15 minimum wage for all workers contracted by the city.

Yet more needs to be done, Council members and advocates say, to meet the demands of a sector whose workers are increasingly in need of the types of safety net programs (like Medicaid and food stamps) that they help to provide for others. The extra $25 million in funding is a relatively small ask in terms of the city’s overall $82.2 billion executive budget, said some present at Thursday’s rally.

“The city relies on nonprofit human services providers to deliver essential services on their behalf, but government contracts continually fail to cover the full cost of programs and payment is often late and unpredictable,” said Allison Sesso, executive director of the Human Services Council. “This chronic underfunding prevents nonprofits from being able to make important investments in things like technology, building maintenance, and employee training, which compromises the quality of important programs and services on which countless individuals and families depend.”

Thursday’s rally and the letter to the mayor come after two oversight hearings on contracts in the past year, one of which was prompted by the release of a report from the Human Services Council that painted the picture of a sector in crisis: underfunded contracts with the city create budget gaps and diminish the quality of services nonprofits can provide, and contract payment is chronically late, forcing providers to turn to costly borrowing to meet their organization’s needs, often accruing interest that is not covered by government contracts.

“If the city wants to build a bridge, if the city wants to build infrastructure, the city puts money in the budget into that. And if costs go over, we put more money in the budget to do that. That’s what we do for infrastructure in this city, and that’s what we have to start doing for our human services contracts,” Rosenthal said at the rally.

“If costs go over, we have to put more money in the budget,” Rosenthal concluded, returning to a comparison she made during the last contracts oversight hearing about the fact that many human services nonprofits are told to seek grants and other funding methods to account for the expenses that their government-funded contracts do not cover. At the time, Rosenthal pointed out that the city would never hire a construction company to build a $40 million bridge, then say to the construction company, “‘We’re going to pay you $35 million. Try to get philanthropy, foundations, or other jobs that you do to pay for the remaining $5 million.’”

***

by Meg O'Connor, Gotham Gazette

@megoconnor13 @GothamGazette