Inside the Numbers: Mayoral Campaign Spending

Mayor de Blasio at his reelection headquarters (@BilldeBlasio)

As New York City’s campaign season hurtles toward the September 12 primaries and November 7 general election, bringing new flurries of fundraising and spending from mayoral candidates, attention has largely been focused on the ‘raising,’ with a few recent donations getting headlines.

Less examined has been the spending, and not for a lack of it; according to filings with the city’s Campaign Finance Board (CFB) incumbent Mayor Bill de Blasio alone has parted with over $2.48 million in campaign funds this cycle, far outpacing any rivals still in the race (real estate executive Paul Massey, who abruptly suspended his campaign for the Republican mayoral nomination in June, spent $3.7 million in addition to the $1.1 million he loaned his campaign, and has over $300,000 in outstanding liabilities). All numbers have yet to be audited by the CFB.

The mayor’s not the only big spender: security contractor Bo Dietl, who failed to get on the Republican ballot line but is running for mayor as an independent, has spent over $620,000. Rocky De La Fuente, a wealthy businessman who has said he would suspend his campaign after being knocked off the Republican mayoral primary ballot, though he has yet to officially do so, has spent over $350,000 in addition to $250,000 in loans to his campaign. State Assemblymember Nicole Malliotakis, the presumptive GOP nominee for mayor, has spent over $160,000 and has almost $30,000 in outstanding liabilities.

Other than Massey’s extraordinary spending, the largest storyline on the expenditure front thus far has been Democratic mayoral candidate Sal Albanese, who had to raise and spend somewhat feverishly in recent weeks in order to qualify for an official, televised primary debate against the incumbent mayor, de Blasio.

Albanese, a former City Council member in his third official mayoral run, has spent over $185,000 as of the mid-August filing with the CFB, of which almost $134,000 was spent in the latest filing period encompassing July 12 to August 7. The ramped-up spending was part of his push to qualify for the first Democratic primary debate, to be held Wednesday, August 23. The city’s Campaign Finance Act requires that candidates who participate in the city’s matching funds program raise and spend 2.5 percent of the campaign’s primary expenditure limit ($174,225 for mayor), to participate.

The other contenders looking to unseat de Blasio in the Democratic primary have also been spreading the wealth. Tech entrepreneur Michael Tolkin – whose estimated $5 million in-kind contribution to his campaign Gotham Gazette reported on before he added more in-kinds that he valued at $2.95 million – has directly spent a separate $226,000 on the race, with close to $120,000 in outstanding liabilities.

The full expenditure limit for mayoral races is $6,969,000 each for the primary and general races, though no participating candidate seems to be in any danger of surpassing the cap. Dietl and Tolkin are not participants in the program, which is run out of CFB and provides candidates meeting certain criteria with public funds matching eligible contributions. Malliotakis and Albanese are both trying to hit the threshold to begin receiving matching funds from the CFB.

So where has the money gone? Below is an overview of expenditures by candidates spending at least the CFB debate qualification threshold who are still in the race: de Blasio, Dietl, Malliotakis, Albanese, and Tolkin. All filings are self-reported, some expenses have overlaps, and campaigns employ different reporting guidelines, so figures are approximations:

Bill de Blasio (Democrat)

Total Spending (including liabilities): $2.48 million (mouse over the graph for more detail)

Over 34 percent – more than $860,000 – of de Blasio’s spending has been directed towards consultants.

At least four consultants or consultancies have been paid over $100,000 each by the campaign, with Hilltop Public Solutions taking in the most at over $224,000 total in general consulting and management fees since February of 2016. Close behind is the progressive-focused firm Revolution Messaging, which has been paid about $222,000 since October 2016 in digital consulting and website development fees.

Ross Offinger, a fundraiser and former de Blasio aide who fundraised for the now defunct Campaign For One New York and was ensnared in the ensuing controversy when the nonprofit was investigated for facilitating pay-to-play with the mayor, was paid about $164,000 in finance consulting and fundraising fees. The payments began in November of 2015 and have continued throughout the scandal and investigations, which ultimately did not lead to criminal charges.

BerlinRosen, the communications firm with close links to the mayor, has been paid over $115,000 for consulting work since February 2016.

Wages make up almost 30 percent – about $740,000 – of de Blasio’s campaign spending.

Just over $200,000 of this appears to be payroll taxes processed through ADP Payroll Solutions, which was also paid separately for professional services related to the processing. Elana Leopold, the campaign’s finance director, is the staffer that’s been paid the most overall, more than $140,000 since April 2016. Phil Walzak, who worked on de Blasio’s 2013 campaign, then in City Hall, and is now a communications and overall strategist for the reelection campaign, has been paid about $100,000. Walzak left the de Blasio administration for the campaign in October 2016.

A series of other staffers have been paid $50,000 or less.

The campaign has spent about 13 percent, or some $320,000, in fundraising expenses beyond personnel, the largest of which was $41,100 in fees for the online fundraising platform ActBlue. Other expenditures are largely for catering and venues, like a $30,931 payment to the Sheraton Hotel for a November 2015 event.

About 9 percent, or some $230,000 of spending, has gone toward polling, all to the same firm, Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research, making it the single entity to have received the most money from the campaign. It was paid on six separate dates between October 2015 and the beginning of this month for costs associated with research, travel, and polling.

Just over $150,000 in de Blasio campaign costs, or 6 percent, were dedicated to rent and office expenses, including almost $67,000 to the coworking and office space company WeWork. Until recently opening its Brooklyn campaign headquarters, the campaign used WeWork space.

Another $100,000, or 4 percent, went towards professional services, including close to $79,000 in legal services provided by the law firm Kantor, Davidoff, Mandelker, Twomey, Gallanty & Kesten, P.C., which was also paid almost $51,000 in consulting services. The remaining $89,000, about 3.6 percent, went to other expenses like petition collection and ads.

Nicole Malliotakis (Republican)

Total Spending (including liabilities): $194,395 (mouse over the graph for more detail)

About $61,000, or 31 percent, of Malliotakis’ spending has gone to consultants, though she does not appear to have a dedicated campaign staff and has not paid any wages, meaning even her campaign spokesperson Rob Ryan is listed as a consultant. Ryan is also the most paid consultant, having received $19,641 since the beginning of June, about a month after Malliotakis launched her candidacy. Consulting fees of $15,000 have also gone to the Staten-Island based PR firm The Von Agency – run by political operative and former Republican County Chair Leticia Remauro – which has also provided roughly $29,800 in professional services related to media management and public relations, and $10,000 in advertising, which is included here in the promotion category. Other professional services, which together make up roughly $44,000, or about 22.4% of spending, includes $8,000 to the Staten Island Advance for online impressions of their work.

Promotion, including campaign literature, the cost of website registration and maintenance, and advertisements, accounts for about $41,000, or 21% of spending. Almost $14,000 of it went to Luke’s Copy Shop for campaign mailers and other literature. About $16,000, or 8 percent, was spent on rent and office supplies, including $13,750 to KRE, LLC for an office space, about $14,400 – just over 7 percent – went to fundraising expenses, and $12,000 – 6 percent – went to the firm Barry Zeplowitz & Associates for polling. The rest, some $6,600, went to assorted other expenses.

Sal Albanese (Democrat)

Total Spending (including liabilities): $185,802 (mouse over the graph for more detail)

About $87,000, or almost 47 percent, of Albanese’s spending went to promotional materials for his campaign, most of it to a small Minnesota-based firm called North Woods advertising. The firm is run by Bill Hillsman, a longtime collaborator of the Reform Party, which endorsed Albanese (he’ll appear on the general election ballot on the Reform Party line regardless of the outcome of the Democratic primary).

North Woods was paid a total of $83,000 in a deposit, video production, and digital ad purchasing for advertising related to the campaign. Additionally, the firm was paid $46,903 in consulting costs, including retainers, and travel expenses. A good portion of this spending was likely related to the development and promotion of the “de-Blah meter” that Albanese’s campaign launched August 3, a gimmick that allows users to rate “How Bad is Mayor de Blasio?,” as the campaign put it.

Albanese’s campaign has also paid about $13,600 in consulting costs to LCG Communications, the PR firm belonging to his campaign spokesperson, Linda Cronin-Gross, rounding off the roughly $60,500, or 32.6 percent, that the campaign spent on consultants.

The campaign also spend almost $22,000, or near 12 percent of spending, on expenses associated with gathering petitions to get Albanese on the ballot. Only about $1,250 of this was spent on printing the petitions, while the rest went to other candidates who agreed to jointly pursue petitions with the campaign, probably using their own staffers and volunteers.

Just over $9,000, around five percent, of Albanese’s expenses through the most recent filing went to fundraising expenses, and $5,800, or about 3 percent, was spent on professional services encompassing a law firm and website design.

Bo Dietl (independent)

Total Spending (including liabilities): $641,389.18 (mouse over the graph for more detail)

Dietl spent over $307,000, or about 48 percent, on promotion of his campaign largely through Facebook and other online ads, and TV ads. Most of this went to two companies: Jump 450 media, which was paid over $147,000 for digital and Facebook ads in addition to $81,000 in consulting and services for media consulting and website work, and Political Communications Advertising which was paid $150,000 for the purchase of television ads.

About $195,000 in spending, or over 30 percent, went to consultants.

In addition to the consulting fees paid to Jump 450, Dietl gave the firm Polsinelli Public Affairs $40,000 in consulting fees related to PR and public relations services. Several campaign strategists and operatives similarly appear to have been paid as consultants, including campaign members setting up phone banks. Roughly $36,600, or 5.7 percent of spending, went to professional services costs, including credit card fees, website work, and $10,000 to attorney Martin Connor for legal services.

Some $35,000 or about 5.5 percent, went to costs associated with fundraising, mostly for food and beverage services. Almost $34,000 went towards office expenses including phones, office catering, and office supplies, and a bit over $27,000 went to wages.

Michael Tolkin (Democrat)

Total Spending (excluding in-kinds, including liabilities): $338,912.21 (mouse over the graph for more detail)

The bulk of Tolkin’s direct spending went to petition-gathering, with spending nearing $114,000, or about 33.6 percent. Most went to the firm Ardleigh Group LLC, which received $108,707. About $81,000, or almost 24 percent, was spent on consultants, including $50,000 to marketing firm Brand Knew LLC for marketing consulting services. Brand Knew also received over $71,000 in professional services fees for branding and marketing work, as well as media buying. It was also paid almost $15,000 in unspecified advance fees, which we are categorizing as “other.”

The rest of the consulting fees went to the law firm Falcon Jacobson & Gertler LLP, which also took in in $21,000 in professional services fees for legal compliance work. About $40,000, or nearly 12 percent of spending, went to promotional materials, including over $24,000 to Pasadena Pictures for video production work. As Gotham Gazette previously reported, Tolkin has also declared millions of dollars in in-kind contributions to his campaign.

***

by Felipe De La Hoz, Gotham Gazette

@FelipeDLH @GothamGazette

Five Democrats Will Be On The Mayoral Ballot, But Only Two Will Debate

Mayoral candidate Robert Gangi (photo:@GangiForMayor)

The first official debate in the Democratic mayoral primary is set for Wednesday, August 23, where Mayor Bill de Blasio will face former City Council Member Sal Albanese. But three more Democrats, all of whom will be on the September 12 ballot, failed to qualify for the debate and are crying foul that the Campaign Finance Board’s eligibility criteria are excluding them from participation.

For candidates to qualify for the first of two official CFB primary debates, they must have raised and spent at least $174,225, which is 2.5 percent of the $6,969,000 primary expenditure limit.

For the second “leading contenders” debate, for Democrats on September 6, a candidate must meet the fundraising and expenditure threshold as well as one of three additional criteria. These include an endorsement from a citywide, statewide or federal elected official who represents the area covered by the election; or an endorsement from a organization with 250 members; or “significant media exposure” in the 12 months before the election, defined in this case as 12 appearances in print, television, digital, or other local media.

Only de Blasio and Albanese have met the criteria for both primary debates. As of the latest filing, for mid-August, de Blasio has raised $4.8 million and spent $2.4 million, and recently received a public funds matching payment of $2.5 million, giving him $4.9 million in cash on hand. Albanese has raised just over $191,000 and spent $185,000, leaving just over $5,000 in his campaign account as of the filing. He has not yet qualified for matching funds.

Candidates who participate in the CFB’s public matching funds program must appear in the debates if they qualify. For non-participants, inclusion in the debates is not guaranteed, the debate sponsors can choose to invite them.

The three other Democratic candidates on the ballot -- attorney Richard Bashner, police reform advocate Robert Gangi, and tech entrepreneur Michael Tolkin -- did not meet the threshold for the first primary debate. Both Bashner and Gangi have struggled to raise the necessary funds; Tolkin is the sole candidate of the bunch to not participate in the public funds program and would need to be invited on to the debate stage by sponsors.

Bashner, Gangi, and Tolkin are all protesting the CFB requirements and the fact that they will be on the outside looking in when de Blasio and Albanese face off. Even Albanese has criticized the requirements, which he barely met after a furious spending spree, and made an argument for a different threshold.

In the 2013 Democratic mayoral primary, the debate thresholds were far lower: candidates had to raise and spend $50,000 but they also had to have received 2 percent in either a Quinnipiac University Poll or Marist Poll. Those thresholds were changed late last year through legislation passed by the City Council -- sponsored by Council Member Ben Kallos, chair of the governmental operations committee -- and signed by de Blasio that increased the debate standards to the current 2.5 percent of the expenditure limit, as well as disqualifying loans or outstanding liabilities as counting towards that expenditure.

The bill was based on one of 14 recommendations by the CFB in its 2013 post-election report, which pointed out that debate thresholds had remained unchanged since 2005 while expenditure limits had increased more than 20 percent. “An increased standard, tied to the expenditure limit, is a better objective indicator of viability,” the report stated, recommending the increase.

Bashner has taken particular issue with the bill, insisting that it was a conflict for Mayor de Blasio to sign it into law since it has largely benefited him. The Brooklyn-based attorney and community board member has raised about $118,785 and spent $104,000, but $50,000 in contributions were a personal loan he made to his campaign.

In a letter to the CFB on Monday, Bashner called the bill that changed the debate law the “Incumbent Protection Act” and called on the board to allow all the mayor’s challengers to participate in the debates. At the very least, he argued, those who have met the 2013 threshold of $50,000 should be included. “Voters deserve the opportunity to hear where each of these challengers stands on the critical issues facing our city,” he wrote. “To silence the voices of these candidates is to impede democracy.”

Council Member Kallos defended the legislation, saying the CFB’s recommendation to increase the threshold was a “reasonable” one. “The piece that I found to be important was that candidates had to actually be spending money towards winning an election and that loans and liabilities wouldn’t count,” he said in a phone interview, insisting that the effect was two-fold. “Wealthy people couldn’t just write themselves a loan that they intended to pay back fully,” to get into the debates. “It also just changes it from a situation where people could loan and spend money that was illusory as opposed to raising and spending actual dollars.”

At one point, it did seem that de Blasio would commit to an open debate with his opponents. He initially seemed reluctant, insisting in a July interview on NY1, “We’re going to follow the CFB rules.” None of his opponents had qualified for the debates by then. The mayor then changed his position, saying in an August 3 tweet, “Regardless of CFB requirements, I'll be on a debate stage before the Sept 12th primary.”

Albanese criticized the mayor’s flip-flop, saying de Blasio issued the statement “when he saw that I was gonna blow past the threshold.” “I don’t find that to be a good government position, it was more of a political, expedient position,” he added.

It’s unclear if the mayor will end up debating all the candidates on the ballot. "Under Mayor de Blasio crime is at record lows, jobs are at record highs, and New York City is building affordable housing at a record pace. We are happy for any opportunity to talk about the Mayor’s record and we look forward to debating whoever the CFB and debate sponsors decide to include,” said Dan Levitan, a spokesperson for de Blasio's campaign, in an email.

Gangi and Tolkin have directed their ire more towards the CFB, taking turns to condemn the debate requirements and the board itself.

"The CFB's decision is a disgrace,” Tolkin said in a statement Tuesday. “It is reflective of a system virtually designed to keep non-politicians out of the election process. We are studying this decision closely and considering a range of options; however, it is clear that a comprehensive review of the CFB’s decision-making process is long overdue.”

Tolkin has taken a peculiar approach to his campaign finances, showing almost $8 million in personal in-kind contributions to his campaign, which are also counted as expenditures. But the CFB determined that those did not qualify him for the debate. Nevertheless, Tolkin challenged de Blasio to participate in three additional debates before the primary with all the Democratic candidates. “Mayor de Blasio’s unwillingness to participate in debates with the full slate of candidates is an obstruction to a fair and transparent primary process - one that he was afforded as a candidate in 2013,” he said.

For Gangi, campaign fundraising has been an even bigger challenge. He has raised only about $88,000 and spent just over $75,000. But, like Bashner, he lent his campaign a significant sum, $74,000, which would not count towards the contribution limit for the debates.

In a campaign statement on Tuesday, Gangi said the financial thresholds “are inherently unfair and undemocratic” by favoring wealthy candidates and incumbents with access to deep-pocketed donors. He was particularly incensed that he had been excluded after the CFB had issued public funds to de Blasio’s campaign partly based on a de Blasio campaign “statement of need” that pointed to Gangi as one of the mayor’s main competitors. “On what basis does the CFB then decide that de Blasio does not have to debate me?” he wondered.

“If my campaign is part of the rationale for granting the Mayor an extra [$2.5] million in tax payer [sic] matching funds, then it should have sufficient standing to earn a seat at the debate table,” he added.

CFB spokesperson Matt Sollars said in an email that the new thresholds were adopted in advance so all candidates would be aware of them. “City law sets objective, nonpartisan criteria for eligibility to participate in the citywide debates,” he said. “These criteria ensure that voters get a robust debate among candidates who have demonstrated public support.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Crucial Weeks Ahead for Potential Rezoning of East Harlem

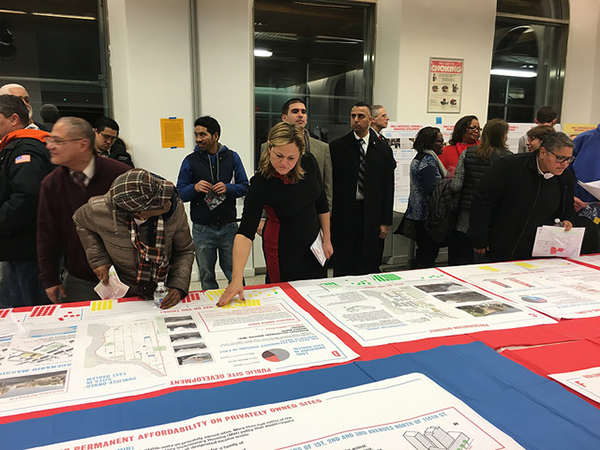

Mark-Viverito at East Harlem planning session (photo: Samar Khurshid)

The de Blasio administration’s plan to significantly alter a large section of East Harlem is in the middle of a contentious process, with its fate unclear. The proposed changes to land use rules and infusion of community development resources -- part of the administration’s larger efforts to build more housing, some of it with affordability requirements, and improve neighborhoods -- have not been to the liking of key elected officials and the window for negotiations will close before the end of the year.

The East Harlem rezoning plan has hit several bumps in the road as it moves through the city’s process for designing and approving changes to the type of development that is permitted and resources the city will bring into a particular area. Namely, the city’s current proposal faces disapproval by City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, who represents East Harlem, and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer.

The City Planning Commission formally began the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process for the East Harlem rezoning plan when the proposal was released April 24, followed by the Borough President’s recommendation earlier this month, in which Brewer put forth her non-binding vote of no confidence.

Next, the City Planning Commission will hold a hearing August 23, followed by a City Planning Commission review due by October 2. Afterwards, the City Council has 50 days to vote on the proposal, which can be tweaked within certain parameters acceptable to the City Planning Commission.

East Harlem is one of 15 neighborhoods that the administration identified early in 2015 as potential areas where the city could build significant amounts of new housing, some of it with affordability requirements, with the goal of boosting local communities through other means as well, including retail and open space, job creation, new school seats, and better transportation infrastructure. The rezonings are a part of de Blasio’s goal of creating and preserving 200,000 units of affordable housing across the city over 10 years. Along with the rezoning of parts of East New York, in Brooklyn, a plan to rezone East Midtown just passed, though it is largely focused on creating new and modern office and commercial spaces.

East Harlem could be the second major neighborhood rezoning of de Blasio’s tenure, but, like in East New York, the administration must negotiate with local stakeholders, especially Mark-Viverito, the local Council rep whose opinion is the most important in the process.

Mark-Viverito will negotiate with the de Blasio administration until there is a plan to her liking, or she will kill the rezoning. The speaker is term-limited out of office at the end of this year (two leading candidates vying to succeed her have also criticized the de Blasio administration’s plan) and has the opportunity to pass the rezoning before she departs.

Mark-Viverito wants to make a deal work. She has seen the rezoning of East Harlem -- especially the affordable housing and community development that would come with it -- as key to her legacy as she prepares to leave the City Council. She helped lead the development of a community-based blueprint, East Harlem Neighborhood Plan, that she and others believe the city has not hewed close enough to in its proposal.

At a recent news conference, Mark-Viverito expressed her displeasure with the city’s process, and criticized the administration for ignoring the East Harlem community voice. “We all took ownership for that process so we stand very strongly behind the recommendations of the steering committee of the neighborhood plan,” she said August 9, when asked by Gotham Gazette about Brewer’s recent opposition and negotiations about the plan.

“What City Planning presented flew in the face of all of that, and it was very disrespectful to all of the thought and workings of the community, and I think Gale [Brewer] strongly spoke to that in her statement,” Mark-Viverito said. “We had thousands of people that participated in that process,” she said. “It was nothing to really sneeze at. And I’m really, really proud of that effort.”

Mark-Viverito made mention of the numerous community representatives were involved in the planning process with the City Planning Department, and that the community has made its needs and wants clear. The Neighborhood Plan, a joint effort involving CB11, Brewer, Mark-Viverito, and advocacy group Community Voices Heard, is a more wide-reaching document than a rezoning proposal, including recommendations on everything spanning NYCHA repairs, public safety reforms, tenant protection and park space. The comprehensive 138-page analysis also includes specific models for ratios of market-rate to affordable housing for newly developed buildings. Undergirding the report and the entire conversation is an estimate of 12,000 East Harlem households that the report classifies as in need of affordable housing.

East Harlem rezoning, whatever form it winds up taking, will create additional housing, both affordable and market-rate, as well as commercial space, by upzoning much of the Upper Manhattan neighborhood, often referred to as El Barrio.

By its current design, the rezoning would allow buildings to stretch up to 30 stories between 104th and 126th Streets in the eastern part of the area and between 126th and 132nd in the western portions. Currently, there is a 120 foot, or ten-to-twelve stories, height restrictions on parts of 125th street and surrounding areas while the rest of East Harlem are not subject to specific height limits. According to the City Planning Department, the upzoning would create approximately 3,500 rental apartment units under the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program, which set asides a quarter of new housing for affordable housing in any new development approved by the city in a rezoned area. The commission estimates the upzoning would spawn 122,000 square feet of commercial space along with 27,500 square feet of office and industrial space.The proposal also includes height restrictions on units built on parts of Lexington Avenue and mandatory apportioning of more affordable housing units in the densest of new developments.

Still, elected officials representing the area, in agreement with Manhattan Community Board 11’s stance, fear the upzoning will not sufficiently benefit low-income residents of the area, which has a high poverty rate, and will adversely affect mom-and-pop stores, accelerate gentrification, increase property prices, without enough affordable housing to meet the area’s needs.

On August 3, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer came out against the administration’s current proposal. While she reaffirmed support for the general idea of rezoning East Harlem, she explained she is not convinced of the merits of what the city put forward. "A rezoning done the right way offers the opportunity to create many new affordable units, including units affordable to low-income East Harlem residents, while actually reducing the effects of gentrification and reinvigorating neighborhood small businesses and retail,” she said in a statement announcing her opposition. "What the administration has put in front of us, however, is rezoning done the wrong way.”

Brewer went on to cite concerns about gentrification, affordability and building heights, all of which she believes are better addressed in recommendations put forward by Community Board 11. Community Board 11 rejected the proposal, though, like Brewer’s, the vote is not binding -- ultimately, the decision is up to the City Council, which almost universally follows the lead of the local Council member, in this case Mark-Viverito.

Mark-Viverito has worked to convene a “Rezoning Task Force” which has met periodically from January to April of this year.

"This proposal concentrates new development in too small an area with too much density, likely worsening the effects of gentrification,” Brewer said, echoing CB11’s criticism. “This proposal lacks a meaningful preservation plan and sufficient up-front commitments to save existing affordable housing units,” the borough president added.

Brewer also issued a list of recommendations for the city to adopt to make the plan more palatable to the community. The list includes reclaiming lost affordable housing units, lowering the density of potential buildings to preserve neighborhood character, and providing more affordable housing units to low-income residents of the area, particularly those making less than 30 percent of the area median income, which amounts to $23,350 for a household of three.

Despite Mark-Viverito’s frustration and Brewer’s disapproval, the effort to rezone East Harlem is far from dead, with negotiations to tweak the plan ongoing.

Mark-Viverito, taking note of the time she has remaining in the Council, said she would continue to advocate for the community’s recommendations. “So that’s what I’m going to be doing in the months that I have to discuss and analyze this rezoning, is to really advocate for the recommendations the community put together,” she said. “We’re in the process of working through that, and I take that plan as a guide in terms of my negotiations with the city. So I’ve been pushing them on a lot of the things that are outlined in that plan.”

But Mark-Viverito’s opposition, should it persist, would effectively serve as a death knell for approving the current plan, or something close to it, any time soon.

At a news conference on August 7, Mayor de Blasio acknowledged that dynamic when asked by Gotham Gazette about the status of rezoning talks and Brewer’s opposition to the East Harlem plan. “This rezoning is unusual compared to all the others because it’s the Speaker’s own district,” de Blasio said. “I think what’s good is when you then hear those concerns and try to work them through and try to find a solution that you both feel pretty good about. And certainly, most importantly, the person who matters the most is the representative of that district in the Council.”

De Blasio said there is still time to iron out the differences in order to craft a plan that meets both the administration’s preferences and the community’s needs. “We’ve had vocal conversations about the rezoning and will continue to…And there’s plenty of time to do that,” de Blasio added. “So we’ll continue having those conversations.”

The process for approving a rezoning is long and multifaceted. Each proposal must go through ULURP, a process that involves a mixture of behind-the-scenes machinations and public hearings with the aim of creating an upzoning blueprint which includes input from city planners, elected officials, and relevant communities. Rezonings typically take several months, if not longer, to make their way through ULURP. The East Midtown rezoning, for instance, was in the pipeline in different iterations for several years before being approved by the City Council on August 9th.

A spokesperson for the City Planning Department said the process has already incorporated additional community input.

On August 7, the CPC issued a technical memorandum, called an “A-Text,” or amended text, which addressed concerns coming from the local community board and elected leaders. This particular iteration of the rezoning plan includes height restrictions on buildings on 3rd Avenue, the Park Avenue Corridor and Lexington Avenue -- provisions not included in the original plan.

“Adding this ‘A-text’ alternative allows for consideration of additional options on shaping the future of East Harlem,” said the CPD spokesperson in an email. “Together with the certified application, the A-text enables deliberation on a wide array of options to protect neighborhood character, increase affordable housing and spur job-generating development in East Harlem. We hope that this provides an environment for a more robust public discussion on the development of the final rezoning plan.”

The East New York rezoning, passed in 2016 and seen as a model for others to follow, like East Harlem, includes infrastructure investment, a new school, and a career center to help those seeking jobs, along with the central goal of paving the way towards creating more housing units.

The rezoning has also become a key issue in the race for Mark-Viverito’s seat. If the proposal is not enacted this year, the issue will be passed along to the next Council member to represent the district.

Two leading District 8 candidates -- State Assemblymember Robert Rodriguez and Diana Ayala, the speaker’s former Constituent Services Director and Deputy Chief of Staff -- also oppose the administration’s plan.

Rodriguez and Ayala, both Democrats, feel the city did not adequately adhere to the community’s input, which Rodriguez insisted was a difficult and crucial component to the process.

“I remember how long those meetings go and how hard it is to get consensus on these things and in this case they spoke very clearly,” Rodriguez said at an August 8 candidate forum in an East Harlem community center. “They’re against it and they provided some reasonable conditions. So I stand with the community board against the plan.”

Rodriguez was not convinced the plan would have much benefit for lower and middle-income residents, a very large combined chunk of the neighborhood, which has seen early waves of gentrification. “[I]t’s an aspirational goal that you’ll be able to get some affordability out of the percentage that is affordable in the new developments,” he said. “So what we’re saying is that we hope that the developers take this incentive after we’ve created wealth for them and then go through the lottery process and hope that our residents get in there? Where’s the mom and pop stores?” Rodriguez wondered.

He voiced concern about what new developments would do to help low-income residents, such as those who earn less than 30 percent of AMI. “What’s in it for them? Nothing!” Rodriguez said. “What is the benefit for residents of East Harlem?” he continued. “Are we just going to hope that we’re going to be able to get affordability?”

Ayala, who has been endorsed by Mark-Viverito, explained her opposition to the city’s plan at a candidate forum. “I think the city’s proposal is very upscale,” she said. “I would like to see deeper affordability as part of the plan. I would like to see more long-term affordability than in the current plan,” she said. “I want to see smaller buildings, I’m not a fan of huge towers,” Ayala said, voicing similar criticism when the topic again came up at the August 8 forum.

In an interview with Gotham Gazette, Ayala said many residents in her community are unhappy with the plan. “Well, they fear that they’re going to be pushed out,” she said. “And they fear that, y’know, we’re going to have all these luxury, tall buildings that are going to change the character of the community and the culture is going to evaporate, [and the neighborhood is] not going to be Harlem anymore,” Ayala said. “I can sympathize because I live in the community, too, and that’s the last thing I want to see.”

***

by Sam Raskin

@samraskinz @GothamGazette

With reporting by Felipe De La Hoz