A Citywide Office for Sexual Harassment Prevention? It Almost Happened 25 Years Ago

Former Mayor David Dinkins, left, with Chirlane McCray (photo: Edwin J. Torres/City Council)

In October 1992, amid sexual harassment scandals that rocked his administration, former Mayor David Dinkins created a task force to examine the issue of sexual harassment in city government. The task force, chaired by late Congressional Rep. Bella Abzug, who led the larger Commission on the Status of Women, submitted its report to the mayor the next year in November, recommending that the city create a Citywide Office for Sexual Harassment Prevention.

The following month, in December 1993 and just two weeks before his mayoralty ended, Dinkins heeded the recommendation and signed an executive order to establish that citywide office as a pilot for two years.

The office was to advise and counsel city employees on sexual harassment issues, as well as mediate when allegations were made. It would be mandated to investigate formal complaints of harassment and discrimination, and recommend disciplinary measures. It was to monitor how city agencies dealt with harassment, evaluate the effectiveness of harassment trainings for employees, and be required to submit quarterly reports on its work to the mayor. And it was to maintain a central repository of formal and informal sexual harassment complaints.

But as administrations switched, Dinkins’ eleventh-hour executive order was lost to the pages of the municipal archives -- the Citywide Office for Sexual Harassment Prevention was never established. The Rudolph Giuliani administration does not seem to have paid any attention to the executive order, which lapsed after its two-year lifespan without being specifically rescinded.

Twenty-five years later, the #MeToo movement’s focus on addressing sexual harassment triggered a cultural paradigm shift across the country and beyond. The New York City Council took stock and passed the Stop Sexual Harassment in NYC Act, a package of 11 new laws to prevent sexual harassment in the public and private sector, through a push led by Council Speaker Corey Johnson and Council Member Helen Rosenthal, chair of the Committee on Women and Gender Equity.

New York State also passed similar legislation last year to address sexual harassment, and more recently held its first public hearing on workplace harassment in nearly three decades, with additional change to the law being pushed by advocates and victims this year and another hearing scheduled for May 24.

A spokesperson for former Mayor Dinkins, who currently teaches at Columbia University, said there was insufficient time to implement the order before his term ended.

“I’ve never heard of it and I’ve been around in almost every administration since,” said Dr. Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, who served as former Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s director of the Department of Personnel, under whom the citywide sexual harassment prevention office would have been established under the order. “In retrospect, it would’ve been a wonderful thing. It’s a horrible thing for any human being to go through those kinds of things.”

When Giuliani came to power, Barrios-Paoli said the administration’s immediate focus was civil service reform and drastically cutting down the city’s workforce. “I don’t recall [the sexual harassment office] ever coming up with me,” she said, lamenting the lost time on addressing the issue. In city leadership, she said, “There was so little awareness of that those days. The consciousness was just not there.”

“I don’t think there was a woman that was exempt. We didn’t think there was any recourse,” she said of harassment in the workplace. “What happens in the change of administration is a lot of things fall by the wayside unless they have a champion.”

The creation of Dinkins’ task force led by Abzug owed largely to the efforts of former Congressional Rep. Elizabeth Holtzman, who was City Comptroller during Dinkins’ term and attempted to examine sexual harassment policies in city agencies only to find a dearth of information.

Only two agencies responded to Holtzman’s requests for information, the Department of Transportation and the Fire Department, and they woefully misunderstood and mishandled the issue of sexual harassment, Holtzman said in a phone interview. “Both responses showed that neither agency understood what the legal requirements were, how to enforce the law and...the people who were victimized by sexual harassment were revictimized by reporting and the people who were perpetrators were allowed to get away with, at worst, a slap on the wrist,” she said.

The glaring lack of a standard across agencies should have invited “a major citywide response,” she said, and Dinkins’ executive order came much too late. “I’m not surprised about Mr. Giuliani’s indifference to sexual harassment. We can see that from his present employment. But I am surprised that both Mayor Bloomberg and Mayor de Blasio have turned a deaf ear to it as well. It’s not a good sign,” Holtzman added, with reference to Giuliani’s work for President Trump, who has a history of misogyny and was caught on tape bragging about sexual assault.

“It just shows how important the MeToo movement is and it shows that nobody’s exempt, including the City of New York,” Holtzman continued, “and even though it wants to tell the country how liberal and progressive it is, the fact of the matter is that when it comes to sexual harassment, they’ve got a lot to account for.”

That accounting is meant to happen under the package of bills the Council passed, which include requirements for reporting on sexual harassment within city government, mandated anti-harassment trainings at city agencies and private employers, and required climate surveys and action plans from city agencies, besides strengthening existing anti-harassment protections.

Merrick Rossein, professor at CUNY School of Law, served on Dinkins’ sexual harassment task force and was also a commissioner on the Equal Employment Practices Commission under both Dinkins and Giuliani. “I do not recall if the Office was functioning by the time Giuliani took office in January 1994. He was hostile to all [Equal Employment Opportunity] enforcement,” Rossein said in an email.

“The City was an early leader in addressing sexual harassment, including mandating training,” he added, noting that he conducted interactive sexual harassment trainings for Dinkins, his deputy mayors and the corporation counsel to show that the city was taking the issue seriously.

“The City should have followed through by establishing the recommended Citywide office. There have been too many cases of sexual harassment from that period until the #MeToo movement and the recent City Council legislation. Too many victims were harmed and tax payers were on the hook for the millions of dollars in settlements, court awards, and lost productivity caused by the disruption of failing to prevent or stop the harassment effectively. The recent legislation is helpful but still insufficient.”

As Rossein noted, the citywide office would have tackled many of the issues that became apparent in city government once the #MeToo movement pushed the New York City Council and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration to look inward at their own approach to a systemic problem.

After the passage of the Stop Sexual Harassment Act last year, the mayor released what data was available on the number of harassment complaints across city government, showing glaring discrepancies in how different agencies approached the issue. The mayor himself conceded that “what’s abundantly clear is there was not a single standard for ‘mayoral’ and ‘non-mayoral’ agencies.” Though de Blasio also downplayed complaints that had come through the Department of Education, remarks he later walked back, and has more recently faced intense scrutiny over his administration’s handling of harassment by his former acting chief of staff.

"Mayor Dinkins was a visionary leader who understood the importance of taking a stand against sexual harassment decades before the Me Too movement, and his executive order was a prime example. The spirit of this order lives on under the de Blasio Administration," said mayoral spokesperson Marcy Miranda in a statement. "Last year, the Mayor signed the Stop Sexual Harassment Act to address and prevent sexual harassment, and we continue looking at ways the City can improve its processes to reduce sexual harassment and all forms of EEO discrimination at work."

Council Member Rosenthal, a Manhattan Democrat and chair of the Committee on Women and Gender Equity, led the way on the Stop Sexual Harassment in NYC Act and was shocked to learn that the city could have acted aggressively so long ago through Dinkins’ order. “What we’ve learned from the MeToo movement is that with focused attention on sexual harassment and experiences of sexual harassment, we are in the midst of changing the cultural tide that allows sexual harassment to continue,” she said. “I can only imagine how much farther along we would be if the...Giuliani administration would have implemented this executive order.”

Dinkins created his task force soon after his own office came under scrutiny for appointing a new deputy mayor who faced allegations of sexual harassment. Dinkins later defended the deputy mayor who would then resign from his post.

Now, the City Council is preparing to hold another hearing on sexual harassment policies next month, where it will examine the implementation of the laws passed last year. Rosenthal said she is waiting to hear if the mayoral administration is “resisting or embracing” the new policies. The Council is currently dealing with sexual harassment allegations against two of its members, and held a mandatory training on Wednesday at City Hall, which was, according to the Daily News, marred by outbursts from another member, Ruben Diaz Sr., who later told the Daily News that sometimes "sexual harassment is a compliment."

Asked if a citywide office would be worth creating, she said the Council would likely receive pushback from the administration. The Equal Employment Practices Commission and the city Commission on Human Rights both currently handle enforcement of laws against sexual harassment, and it’s possible a new agency would be duplicative, Rosenthal noted. But, she said, “I think we have to learn more from our reporting bills to see whether or not the administration is following through on our set of bills that we passed.”

Holtzman praised Rosenthal’s legislation and the overall package the Council approved, but she nonetheless believes the city needs a dedicated office to tackle sexual harassment. “It’s one thing to have reports and it’s another thing to have a commission that has its responsibility rooting out this problem,” she said. “Unless they can show it’s not a problem, why not?”

She continued, “You need to have a proper administrative structure. I remember when I was trying to deal with the problem of Nazi war criminals in America, the government had done nothing about them for more than 25 years and they were finding sanctuary in the United States. I did create an administrative structure in the Department of Justice, which had that as its mission. You have to give an agency a mission and monitor that agency to make sure it carries out that mission, and instead the message was to all city agencies, it’s not a serious problem.”

At the April 25, 2018 news conference when Mayor de Blasio, who worked in City Hall under Dinkins, addressed reporters’ questions about sexual harassment complaints, he noted that the #MeToo movement was leading to a sea change in city government. “So one thing that has come out of this very important movement, this emerged from a social movement in this country that demanded clearer answers from every segment of this society, is we’re aligning all standards on sexual harassment across all agencies,” he said. “And I think that’s going to make a big difference.”

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

Note - This article has been updated with comment from a spokesperson for Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Max & Murphy Podcast: Pressing Immigration Issues, with City Council Member Carlos Menchaca

City Council Member Carlos Menchaca (photo: Jeff Reed/City Council)

May 8, 2019 - Max & Murphy Podcast: Pressing Immigration Issues, with City Council Member Carlos Menchaca

City Council Member Carlos Menchaca, chair of the Council's immigration committee and co-chair of its 2020 Census Task Force, joined the show to discuss a wide range of issues related to immigrant communities and public policy, including whether New York City is really a "sanctuary city."

City Council Member Carlos Menchaca, chair of the Council's immigration committee and co-chair of its 2020 Census Task Force, joined the show to discuss a wide range of issues related to immigrant communities and public policy, including whether New York City is really a "sanctuary city."

Listen to the conversation and let us know what you think -- we're on Twitter @TweetBenMax and @JarrettMurphy. You can listen to the show through the embedded audio below or download the episode wherever you get your podcasts, under "Max & Murphy," and listen to Max & Murphy live on Wednesdays at 5 p.m. on WBAI radio, 99.5FM or wbai.org

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Contentious Bronx Charter Commission Hearing Centers on Voting, Police Accountability Reforms

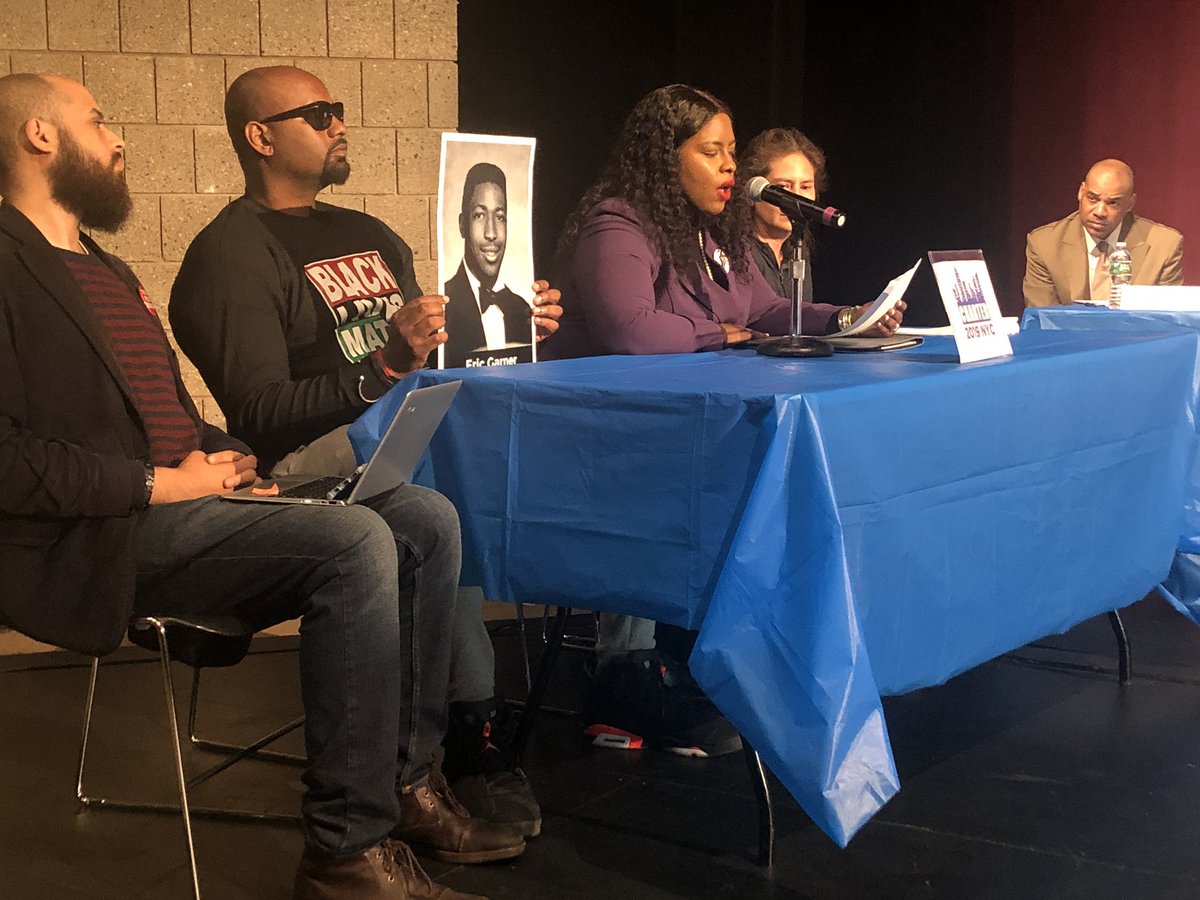

(photo: @Charter2019NYC)

The 2019 Charter Revision Commission held a lively public hearing on its preliminary staff report in the Bronx on Tuesday evening. Public testimony largely focused on boosting support for ranked choice voting, which the commission is pursuing as a likely inclusion of what it will propose to voters on the November ballot, and advocating for an elected rather than appointed Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB), which the commission does not appear to be considering.

After Bronxites offered their opinions, the commission publicly deliberated on the testimonies, where they occasionally butted heads, but largely reinforced their vision of a revamped city charter better guided by community empowerment.

As the commission’s process moves to its final stages, the recently-released staff report outlined a variety of areas for the commissioners to give further consideration and hear public input -- with one hearing in each borough -- as they move toward announcing which changes to city governance they will recommend to voters.

The preliminary staff report moved forward several possible provisions aimed at increasing community participation in governmental processes. The Bronx hearing was the third of the commission’s latest wave of borough meetings, after those in Queens and Brooklyn and just ahead of Manhattan and Staten Island. After taking in the latest round of public feedback and holding private conversations, the commission will his summer decide what to put before voters in November.

In between that decision and the yes or no vote, the commission will attempt significant voter education on its proposals, in part to drum up participation in what is expected to be a very low turnout Election Day. The commissioners will also have to decide whether to present their recommended charter changes to voters as one package or to separate it into multiple parts.

Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. did not submit testimony, despite saying in late March on the Max & Murphy podcast that his office was the in process of brainstorming, but “when the time comes, we’ll come out with our proposals and of course we’ll make them public.”

Diaz Jr. is not alone among the borough presidents; only Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and Staten Island Borough President James Oddo have submitted testimony throughout the charter commission process. Queens Borough President Melinda Katz and Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams have kept their distance. Each borough president has one appointee to the 15-member commission.

While only a few dozen Bronxites attended the meeting at Lehman College, those who did gave passionate testimony, predominantly about election reform, police accountability, and land use. Some current and hopeful politicians also appeared and gave sweeping testimony about the commission’s preliminary report as a whole.

Supporters of an elected CCRB comprised a significant portion of the audience and public speakers. Advocates argued that a democratization of the CCRB, whose members are currently appointed by various government officials, is the best path to holding police officers accountable for wrongdoing. New Yorkers will “elect people like them,” Chivona Newsome from Black Lives Matter Greater New York argued, “community members, mothers, fathers, people living above and below the poverty line.”

The Bronx, she said, is well-equipped to speak to problems with the CCRB. “My beloved borough ranks number two for the most complaints filed in the city,” despite having the fourth-highest population, she said. “The only way bad cops will ever be held accountable is with an elected civilian review board,” she said.

Currently, the City Council, police commissioner, and the mayor each appoint CCRB members. The charter commission’s report put forth the notion of strengthening City Council’s role in designating CCRB members and potentially allowing the public advocate to make appointments. The commission staff further advocated exploring bolstering the legal authority given to the CCRB.

Several Bronxites, however, argued that the commission’s report was inadequate. Hawk Newsome, president of Black Lives Matter of Greater New York, railed against their suggestions and called the report an insult to African-Americans. It was, he said, “a waste of paper and a waste of oxygen for those of you who debated it.”

Hawk Newsome asked commissioner Jimmy Vacca, former City Council Member from the Bronx and appointed to the commission by Diaz Jr., to look up from his phone twice during his testimony. He concluded his impassioned appearance by telling the commission that the NYPD “has all the protection in the world, and we have none. And the reason we have none is because of people like you.” While others on his panel spoke, Newsome held up a photo of Eric Garner, who was killed by an NYPD officer in 2014.

Betty Maloney, a feminist activist, also advocated for an elected CCRB based on the NYPD’s “abysmal failure” in properly addressing sex crimes. She told the commission that after she reported her rapist, a police officer asked her if she was “a prostitute.”

“If you fail to act for justice, whether you’re a woman or a man,” she told the commission, “you will be known by the ever-expanding #MeToo movement for your failure to act.”

Frank Morano, a radio host and political activist, focused on a different theme, but also chided the commission as “beneficiaries of the system,” though he complimented the group for a report that incorporated “hundreds of ideas.”

Morano delivered an animated testimony against the city’s current campaign finance laws. “We still have legalized bribery, we have a system that’s more costly than ever,” he said of the 8-to-1 public matching system the city uses for smaller contributions. “Who are we helping?” Morano espoused the use of democracy vouchers, a campaign finance system used in Seattle that largely eliminates private donations to candidates and engages more people in the process by providing them with money that must be donated to the candidates of their choice. It’s a program favored by charter commissioner Sal Albanese, a former City Council member appointed to the commission by Adams.

Morano closed his testimony by warning against blindly following the commission report. “Please, don’t go along with what the staff recommends,” he said. He implored the commission to put democracy vouchers “on the ballot and let the people vote.”

Several Bronxites attended the meeting to voice their opinion about ranked-choice voting, a reform that would allow voters to rank candidates and avoid costly runoffs. The commission staff suggested studying it further, including around which offices would benefit from the system. Some form of ranked-choice voting appears destined for the final recommendations.

Many testifiers spoke in favor of ranked-choice voting citywide and argued that it would reduce voter disillusionment.

“People should not be afraid to step outside the box and express their true preference on the ballot,” said Debra Rosario from the Bronx Green Party. “It’s hard to get excited about an election when the hope is the lesser of two evils,” said Paul Gillman, Bronx resident from the Green Party New York and 2014 state senate candidate in Queens.

“I don’t think this is an ideological issue,” echoed John Reynolds, a resident of the Bronx for 68 years, “I think it’s an issue of faulty democracy.”

Contrarily, Roxanne Delgado, an activist from the Bronx who frequently testifies at hearings on public policy, spoke out against ranked-choice. She argued that the system disadvantages low-income communities where less effort may be put into voter education. She also worried that a complicated ballot would delay the city’s process of counting votes. “I see no benefits to ranked-choice voting,” she said.

City Council Member Andrew Cohen, who represents the northern Bronx, gave broad testimony supporting provisions like easing the ULURP process, increased police accountability, and strengthening the Conflicts of Interest Board. But much of his testimony focused on his concerns about ranked-choice voting, leading to a lengthy discussion between Cohen and several commissioners.

While he sees the merits of ranked-choice on a citywide level, he said, he fears it “could lead to mischief in a way that might not achieve the goals we want to achieve.” Commissioner Carl Weisbrod, a former official at the city Planning Department and appointee of Mayor de Blasio, asked why Cohen felt ranked-choice wouldn’t lead to elections where the “winning candidate was more fully embraced by the district as a whole.” Cohen answered that he appreciated the idea in the abstract, but feared that if implemented, ranked-choice would empower “people who feel passionately to come up with bad ideas to scheme and get people to vote the way they want.” Both Commission Chair Gail Benjamin and Commissioner Albanese disagreed with Cohen’s assessment.

The topic of land use also appeared to have struck a chord with Bronxites.

Maggie Clarke, founder of Inwood Preservation, argued that rezonings are “straining the very limited air and water resources we have,” and said that the city should curb its rapid development pace. She encouraged the commission to include a measure requiring the city government to fully consider alternative plans during the the land use review process (ULURP) and environmental impact study (CEQR) process.

Commissioner Vacca asked Clarke if a provision allowing for a city official to mandate a 30-day stall in the ULURP process if the community feels they haven’t been engaged would satisfy her critiques. She answered that the problem stretches beyond community input and is endangering the environment.

“This is the only opportunity that we’re going to have to fix the system in a way that allows environmental law not to be broken,” Clarke said.

Adam Weinstein, president of Fipps Houses, urged the commission to “encourage transparency” for the community. “Most folks appearing before community boards should be encouraged to show up long before the certification process,” he said of developers. “Only good things can happen.” He also voiced support for simplifying the complex documentation required of ULURP applicants.

Two GIS, or geographic information system, experts from Lehman College also gave testimony urging the commission to support an amendment to Chapter 48, which deals with information technology and telecommunications. They said that GIS technology helps the city with everything from 311 to superstorm preparation.

Michael Beltzer, a two-time candidate for City Council in the Bronx, gave broad testimony touching on many issues in the commission’s preliminary report. He voiced support for democracy vouchers, an elected CCRB, ranked-choice voting (but suggested limiting the ballot to six candidates), and increased budgetary power for the public advocate and potentially borough president offices.

George Diaz, who’s challenging Assembly Member Jeffrey Dinowitz in next year’s primary, called for more pronounced and earlier involvement of community boards in land use decisions, an “empowered” CCRB, and a reformed and “less punitive” campaign finance system. He also voiced his support for ranked-choice voting, which could potentially benefit him in his 2020 race against the incumbent who has never faced a primary challenger.

“Do me a favor,” commissioner Albanese said, “look into democracy vouchers.”

After hearing 16 people testify, the commission moved into a public discussion, where they reinforced their overarching goals of empowering communities in local governing decisions and expanding democracy.

Commissioner James Caras, a land use expert appointed by Manhattan Borough President Brewer, kicked off the discussion by asking his colleagues how they envisioned consolidating land use and planning documents. Commission Chair Benjamin suggested, “one would rely on the work of the other,” ridding the process of redundancies. Commissioner Weisbrod added that documents should maintain a level of flexibility to “respond to conditions as they arrive.”

Commissioner Paula Gavin, former Chief Service Officer in the Mayor’s Office, said planning documents should be set up in a way to manifest a “unified vision of the city” set by the mayor in conjunction with City Council, the public advocate, and the comptroller.

Commissioner Vacca reinforced his call for stronger borough-based power during ULURP, citing the shuttering of Rikers Island jails and installation of four new jails in each borough but Staten Island as an example of how the process shortchanges the Bronx. The four jails are part of one ULURP bid, Vacca explained, calling them a “package deal.” Commission Chair Benjamin pushed back, saying that ideas within ULURP can be separated and accordingly struck down or approved, but Vacca maintained the need for a stronger borough-specific voice throughout the process.

Benjamin and Vacca butted heads again when discussing the powers of the commission itself: “Jimmy, we’re not a budgeting agency,” Benjamin said in response to Vacca’s suggestion of creating ULURP surveys.

Vacca disagreed, arguing that many of the proposals within the commission’s preliminary report are inherently budgetary––ranked-choice voting, for insistence, will require the city to spend money on voter education.

Some commissioners addressed the occasionally combative tone of the public hearing. “I don’t agree with how everything was phrased today because I don’t think we’re responsible for everything as a commission,” noted Rev. Commissioner Clinton Miller, a pastor from Brooklyn.

Commissioner Sateesh Nori, a Queens-based attorney, quipped on Hawk Newsome’s decision to wear his sunglasses as a pointed sign of disrespect for the commission, in return for what Newsome called their lack of respect for the people of New York City. “I’ve taken off my sunglasses as a sign of respect to you all,” Nori said.

Nori also reminded the public that the commission does not have legislative power, but that voting reform would help in creating legislative changes.

“Our overall goal,” Commissioner Gavin said, “is to strengthen our city and strengthen our democracy.”

***

by Savannah Jacobson

@srjacobson1

@GothamGazette