An Alternative to Suicide By Budget

With Mayor Michael Bloomberg preparing to release his worst-case scenario executive budget this week, possibly containing as much as $1 billion in additional service cuts and thousands of layoffs to close the city's budget gap, the Budget for a Livable NYC Coalition -- a new, growing citywide coalition of dozens of community, civic, labor and religious organizations -- is instead urging a far-reaching revenue proposal.

"Follow the money," they are telling the mayor, just as Deep Throat advised cub reporters Woodward and Bernstein to do in the beginning of their investigation into Watergate. And that money is mostly right here in New York City, not in the closed pockets of Albany or Washington, DC.

The city's continued reliance on additional aid from New York State to close its $3.5 billion gaping budget hole is beginning to feel like suicide by budget. The New York State Financial Control Board recently warned against it, and the New York City Council estimated that $1.9 billion of the city's budget gap -- just under 60 percent -- is the result of harmful actions that the governor has proposed in his state budget! Even though the city sends Albany at least $3.5 billion more in revenue each year than we receive in state aid, this year we will get even less such aid - at least hundreds of millions of dollars less.

Unlike the governor, who sailed through his re-election campaign vigorously denying any coming state fiscal distress, Mayor Bloomberg spent his first year in office seriously addressing the city's economic downturn and the budget crisis he inherited. He and the City Council have already made over $2.6 billion in cuts; enacted the highest property tax rate increase in city history; imposed a staggering number of "user fees" for various public services as well as higher fines for various infractions. Unfortunately, most of these revenue increases and service cuts were regressive, hitting hardest the New Yorkers with the least resources and greatest needs.

But the city is still confronted with at least a $3.5 billion hole in the Fiscal 2004 budget, which begins July 1. And although the mayor has stated his commitment to raising broad-based, recurring revenues to protect essential public services and revitalize the economy, his current gap-closing strategy falls far short of this. He continues to rely on significant additional aid from the state and federal governments that, other than increased homeland security funding, is highly unlikely to materialize. He is also now calling for $1.2 billion in municipal labor givebacks and "productivity savings," which are both unfair and unrealistic; they entail negotiations with multiple unions in a very short period of time, as well as deep cuts in individual workers' benefits. Where is the comparable demand for business assistance and givebacks?

Mayor Bloomberg's only significant proposal for new revenue -- a "reform" of the city's personal income tax that combines a new commuter tax six times higher than the repealed version, with a tax cut of 38 percent for city residents -- has been declared "dead on arrival" by the governor and the majority leader of the State Senate leader, who must approve it. It is, moreover, a thoroughly perplexing proposal, since in just three years, the added revenue from commuters would be canceled out by the tax cuts for residents.

Despite the starkly compelling post-9/11 case for additional state and federal aid, the sad truth is that while we continue to seek it, New York City must prepare to rely primarily on itself, as usual, to balance its budget and begin our economic recovery. Almost two-thirds of the city's annual revenues are raised from city taxes, fees and fines, and we will have to reform these to find additional ongoing revenues to grow, not cut, our way out of our fiscal crisis.

And this is exactly the recipe for survival being pressed by the Budget for a Livable NYC Coalition, which was convened and is being staffed by City Project. It is proposing a progressive revenue package which, if enacted, would generate $3.5 billion in additional recurring revenues for the city, avoid the need for further painful and destructive service cuts, and spread the pain and burdens of the fiscal crisis more evenly and fairly.

The coalition's revenue recommendations "follow the money" to wealthy city residents and profitable businesses, which have so far been insulated from contributing to the city's recovery.

We propose to capture a small portion of the federal income tax windfall, by enacting a one percent income tax increase for residents with incomes above $250,000, which would raise $595 million in new revenue. Our recommended commuter tax is a simple one percent tax, which would, by itself, generate $950 million, almost as much as the mayor's complicated personal income tax reform proposal, but in ongoing revenues.

Of equal importance, the coalition calls on the city's business community to shoulder a fairer portion of the fiscal burden, through revising and restructuring business taxes.

New York City's three major business taxes, enacted in 1966, have undergone only minor changes since then, despite sea changes in corporate ownership structures and business practices. They are outmoded, deeply inequitable, and filled with irrationalities. Unlike the city's personal income tax, whose revenues rise and fall with people's incomes during boom and bust times, revenues from the business taxes together contribute only about 12 percent of city revenues, a share that has remained essentially flat over the past twenty-five years, regardless of whether the local economy was sizzling hot or ice cold.

To remedy this situation, the coalition has made three business tax reform proposals that together would generate $1.19 billion in additional revenue for the city, and ensure that the most profitable businesses contribute a larger share of revenues.

Our most lucrative proposed change affects businesses that form as limited liability partnerships and companies, so-called "LPs" and "LCs." Since the mid-1990s, these businesses have been subject to the city's unincorporated business tax. Originally enacted to apply to small partnerships and sole proprietorships, which were not incorporated and exposed their owners to full personal liability if anything went wrong in their businesses, this tax was set at a very low rate - four percent -- which has never been increased. By contrast, the city's general corporate tax, which applies to over 240,000 regularly incorporated businesses, has an 8.85 percent tax rate.

The coalition is proposing that the city's 6,800 large limited liability partnerships and limited liability companies, which include Bloomberg, LP, and the largest and wealthiest law firms and financial service companies in the city, and which are structured to shield their owners from personal legal liability, have their tax rate equalized to 8.85 percent, the same as the general corporate tax. Doing this would raise $881 million in new city revenues and level the business playing field, where these companies now pay 55 percent lower taxes than comparable businesses because of the fluke of their ownership structure, rather than the level of their profitability.

The coalition also proposes that New York City-based insurance businesses, which were exempted from paying corporate income taxes in 1974, be restored to the tax rolls, and shoulder their fair share of business tax, which would generate at least $200 million in city revenues. Putting them back into the tax pool would also remove the unfair competitive edge their exemption gives them in their non-insurance business ventures, including real estate and financial services, which have become an ever-larger portion of their businesses.

Then there is the matter of the $300 minimum general corporate tax, charged to corporations that, because of tax deductions, exemptions, loopholes or lack of income, do not qualify to pay the 8.85 percent tax rate. This fee, which is paid by over half the city's 240,000 plus corporations, was established in 1966 and never increased; can you think of any of your expenses that haven't gone up since the 1960's? The coalition proposes to increase this minimum fee to $1,000, an increase of just over $58 a month, and still substantially lower than if it merely had been adjusted for inflation since its enactment. (By comparison, a family of four struggling to survive in New York City on $30,000 now pays the city nearly twice the current minimum corporate tax in personal income taxes.) This rate change would net the city $107 million in new revenue.

Finally, the coalition is calling for a reinstated stock transfer tax, which was in effect for decades until the state effectively repealed it. This is a tax on individual and institutional stock transactions, not on the stock market or stockbrokers, and it exists in virtually every major stock market throughout the world. The proposal is to reinstate it at a mere penny-a-share, or 80 percent lower than the original tax. If passed, and if the revenues were split with the state, as the coalition proposes, each jurisdiction would be enriched by approximately $760 million a year.

Some would argue that the coalition's proposals could lead to the wholesale exodus of businesses from the city. This is the standard claim of the no-taxes/no-government crowd. It is an unsupported assertion. Not only are the changes fair and reasonable, but more important, they will help guarantee continued funding for public services, resulting in streets that are free of crime and filth, an educated workforce, and good public transportation - all of which recent studies show businesses consider far more crucial factors than the level of taxes in their decision where to locate. Or, as our businessman-mayor put it, "Any company that makes a decision as to where they are going to be based on the tax rate won't be around very long." In addition, since the mid-1990s, New York State has slashed business taxes so many times and so deeply, that the state dropped from ninth to 25th place among all states in terms of corporate income tax rates, with city businesses receiving the full benefit of these enormous tax savings. It is time for them to give a little back.

All the coalition's measures must also, unfortunately, be approved by the state legislature, because the city has direct control only over its property tax rate. But all except the commuter tax and stock transfer tax apply exclusively to city residents and businesses, which should significantly increase their likelihood of passage. If passed, these proposals would not only close the city's budget gap, but broaden its tax base, increase long-term, recurring revenues to maintain vital public services, and make our tax policies fairer and more progressive by spreading tax burdens to those best able to shoulder them. Not a bad way to turn a huge fiscal crisis into an unparalleled opportunity to create a more solidly funded, livable and compassionate city.

Bonnie Brower is the executive director of City Project, a "progressive, nonpartisan public policy organization."

City Of Dissent

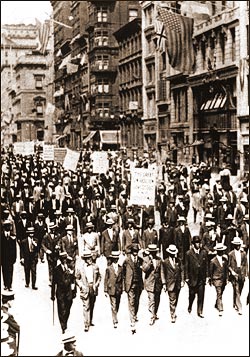

Protest march down Fifth Avenue, 1917.

|

Brian Knowlton joined tens of thousands of other New Yorkers on the East Side of Manhattan on February 25 to protest the U.S. preparation for war in Iraq. And like many others that day, he was arrested -- in his case for not moving when a police officer asked him to.

Rather than simply being given a ticket, Knowlton was held at One Police Plaza and questioned -- not just for his name and address but about his political affiliations and who had accompanied him to the rally. "The detective asked, 'So do you come to these things often?' - something like that," Knowlton recalled.

Confronted with evidence of such interrogations, the police department admitted last week that they had asked similar questions of many people arrested at protests beginning in mid February and had compiled the answers on special "demonstration debriefing forms." Under fire from civil liberties groups, who called the practice "chilling" and "intimidating," Commissioner Raymond Kelly said the department would end the practice.

The police department also has backtracked from its denial of a permit to march for the February 15th mass anti-war demonstration, granting such a permit to a later demonstration. But at the same time the department has not backed down from reviving a practice that was banned almost 20 years ago, the surveillance of political activity. And the federal government, which has already cracked down on the rights of non-citizens, is considering measures that would allow the government to take citizenship away from Americans who support groups the government considers terrorist.

New York, long a center of protest, has in the last several months been what one reporter called "the spiritual center of the anti-war movement." In a city edgy with fears of terrorism, New Yorkers marched, rallied, staged "die ins" and practiced civil disobedience. As activists mounted the first mass protests in New York since the terrorist attacks of September 11, they confronted heightened security concerns head on.

"A national conversation is starting about what kind of country we want to live in and what balance we will tolerate between public safety and private freedom," Matthew Brzezinski wrote in the New York Times magazine. Depending on whether there are further terrorists attacks, he continued, "we may come to think nothing of American citizens who act suspiciously being held without bail or denied legal representation for indeterminate periods or tried in courts where proceedings are under seal."

A HISTORY OF PROTEST, AND SUPPRESSION

The history of dissent in New York goes back a long way -- as have the efforts to suppress that dissent.

One reason for New York's prominent role is because it has long served as the center of U.S. publishing, and the many writers and editors of dissenting publications added to the range of voices heard in the city. New York also has always had the highest concentration of immigrants, who bring their varied viewpoints and, often, an antipathy toward authority learned in the old country. Jewish immigration in the late 19th and early 20th century, for example, spurred the development of an American socialism that was particularly strong in New York. Italian immigrants also played a major role in the early days of the labor movement in New York, demanding rights for workers.

"The matrix of ideas is richer here, and in part it's richer because it reflects debate and discussion overseas as well as at home," says Joshua Brown, director of the American Social History Project at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, who says that for much of its history New York has been "the exception to the rule" of the American mainstream.

But just as dissent has flourished here, so have efforts to suppress it, particularly when Americans feel threatened. "In time of war or national emergency, we respond too harshly in our restriction of civil liberties, and then, later, when it is too late, we regret our behavior," Geoffrey R. Stone, a professor of law at the University of Chicago has written.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln several times suspended the writ of habeas corpus which requires that a court show why someone is being charged. The nationwide crackdown had a disproportionate effect in New York where many people, particularly Irish immigrants, opposed the war. By the early 1860s, writes Kevin Baker, as many as 10 percent of New York City men were arrested, most for dodging the draft or otherwise resisting the war effort.

During World War I, President Woodrow Wilson warned that disloyalty "must be crushed out of existence." Opposition to the war was particularly strong in New York, where settlement house workers, groups championing women's rights, and many immigrants had been against U.S. involvement in the conflict. Some 2,000 people were arrested for opposing the war – including, for example, Mollie Steiner, a Russian Jewish émigré who had handed out anti-war leaflets in the city.

The suppression continued with the Red Scare of 1919 and 1920, when New York State's Lusk Committee tracked down and arrested communists, focusing on immigrants in New York City.

In the 1960's, with much of the country caught up in protest movements, New York did not stand out as much as it has in more politically sleepy times. But dissent thrived here as well, spreading beyond the anti-war movement to such protest movements as the demand for community control of local schools, and the gay rights movement, which got its start in Greenwich Village in 1969 when police raided a gay bar and patrons fought back. Campus protest, which began in Berkeley, moved east most famously in 1968, when students at Columbia University occupied some of the school's buildings to demand that Columbia not build a gym in Morningside Park, a protest to which the administration responded by calling in the police.

While much of the rest of the nation seemed to settle down for a while, protests continued in New York, from the giant 1982 demonstration in Central Park calling for a freeze on nuclear weapons to the acts of civil disobedience in front of police headquarters, after the killing of unarmed Amadou Diallo by undercover New York City police in February, 1999, to the local protests against the U.S. Navy's shelling of the Puerto Rican island of Vieques.

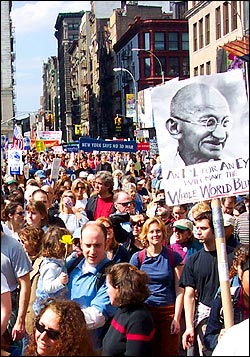

Protest march on 17th Street, 2003.

|

THE ANTI WAR MOVEMENT

The war in Iraq has highlighted once again how New York often stands apart. In much of the rest of the country, business and private citizens have been staging their own crackdown on those who oppose the war.

A security guard employed by a shopping center had an Albany lawyer arrested when he refused to take off a t-shirt reading "Peace on Earth." People at a Houston rodeo spat upon and assaulted a 16-year-old who refused to stand when a flag-waving song blared over the loudspeakers. A boycott resulted in reduced air play on radio stations for The Dixie Chicks after one of the group said she was ashamed that President George W. Bush is from Texas. Last week, the president of the Baseball Hall of Fame canceled the museum's 15th anniversary celebration of the movie "Bull Durham" because Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon (both New Yorkers), who starred in the film, vocally oppose the U.S. war in Iraq. Dale Petroskey, president of the hall, said the actors' comments "ultimately could put our troops in even more danger."

"'Rally 'round the flag,' is the resounding cry heard throughout the nation," said Maurice Carroll, director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute. But, he added, "In New York City, that cry is muted."

A Quinnipiac University poll taken soon after the U.S. attack began found 49 percent of New York City residents opposed to the war, contrasting with a national poll taken in which only 26 percent of Americans opposed the war.

An anti-war activist, Reverend Earl Kooperkamp of St. Mary's Episcopal Church in West Harlem, told a reporter, "This is an unprecedented mass movement and New York is setting the tone."

While supporters of the war, including officials in the Bush administration, see it as a response to the events of September 11th, and say it could help stop terrorist attacks on the United States, some New Yorkers say the exact opposite. The fact that they live in the city that experienced the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history has made them skeptical; they question how war will make them safer.

Activists have urged that the trade center attacks not be used as a justification to wage war. Shortly after the attacks, artists stood silently in Union Square bearing signs reading, "Our grief is not a cry for war." Not in Our Name has called upon the government not to use the September 11 attacks as a justification for roundups of Arabs and Muslims or restrictions on civil liberties.

"New York was the city that suffered the greatest losses in the September 11 attacks, and New Yorkers who are against the war feel a special moral urgency in standing against the wanton attacks on other cities," said Kimberly Dillon, a New Yorker active with the M27 Coalition, which advocates direct action against the war.

As it has for more than a century, the presence of so many immigrants in New York also helps shape the debate here. Andrew Beveridge, a sociology professor at Queens College, said immigrants get information from different sources than other Americans, such as the Arab cable network Al-Jazeera (whose footage is shown on various ethnic television stations), and so come away with a different perspective. The immigrants on his campus – wherever they are from -- "see the U.S. as a big bully."

THE POLICE RESPOND

"In any civilized society the most important task is achieving a proper balance between freedom and order," Chief Justice William Rehnquist has written. "In wartime, reason and history both suggest that this balance shifts in favor of order – in favor of the government's ability to deal with conditions that threaten the national well-being."

With the nation involved in a war on terror as well as a war in Iraq, law enforcement in New York has reacted warily to protests and activism.

Last September, before the anti war movement really got going, the Bloomberg administration asked a federal judge to remove most provisions of the 1985 agreement that limited police monitoring of political activity. The restrictions were instituted after activists filed a class action suit to stop undercover police from watching demonstration and meetings and compiling dossiers on participants.

But police now say the rules, called the Handschu agreement, make it hard to find terrorists before they launch an attack. "It is difficult to imagine a state of affairs more outdated by the events of September 11," police Intelligence Commissioner David Cohen said.

Judge Charles Haight, who had signed the original agreement, apparently concurred and lifted most of the restrictions on the condition that the police agree to guidelines for monitoring their own behavior.

The judge's move could mean a "return to the bad old days of police dossiers on law-abiding critics of government, infiltration and disruption of lawful political activity and organizations, and intimidation and punishment of dissent," Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union told the Village Voice.

The police department also cited security concerns when it denied United for Peace and Justice a permit for a February 15 march past the United Nations to protest the war. The courts upheld the decision.

Instead, the city let demonstrators hold a stationary rally on First Avenue. But that created its own problems. Police directed demonstrators to block-long pens, created with barricades. More than 250 people were arrested, many for trying to get to the rally. Rather than being released with warrants to appear in court at a later date, they were taken into police custody, denied access to lawyers, according to Risa Gerson of the National Lawyers Guild, and, as has now become evident, questioned about their political activities.

At another demonstration, on April 7, police arrested about 95 people, some of whom attempted to block entrances to the Carlyle Group, a private investment group.

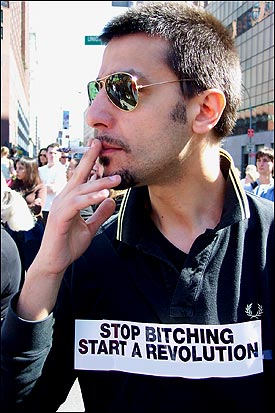

Near Union Square Park, 2003.

|

The demonstrators practicing civil disobedience expected to be arrested. But Beth Andrews, a spokesperson for the M27 Coalition, said she was across the street performing street theater when she was picked up. She and the others remained in custody for about 10 hours. According to Joel Kupferman of the National Lawyers Guild, police asked many of those arrested about their views on Israel, Palestinian rights and terrorism. This is, he said, "an attempt by the New York City Police Department to break the right of dissent."

Commissioner Raymond Kelly said the questioning began as "a good-faith effort on the part of some people in the department to help us determine what resources are needed to police certain demonstrations in the future." It is being stopped, he said because, "we determined that was not that necessary."

While applauding Kelly's decision, the Civil Liberties Union still has concerns about who called for the interrogations and what has become of the information collected. "People have every reason to worry about what the government is doing with information it has no business having," says Lieberman.

A NATIONAL CRACKDOWN

The actions by the New York City police reflect moves at the national level since September 11. The federal government has generally targeted people for their ethnic background, rather than their politics. It has also taken action against mosques and Muslim organizations it believes are linked to terror, such as a Brooklyn mosque that prosecutors charge funneled money to Osama bin-Laden.

But the U.S.A. Patriot Act has allowed wider use of wiretaps on U.S. citizens. The FBI has received increased power to monitor meetings, oversee internet use and send undercover agents into houses of worship. The draft proposal for so-called Patriot II, with its provision for stripping people of citizenship, has sparked alarm among a wide array of organizations.

Attorney General John Ashcroft has said law enforcement needs increased authority to fight terrorism but that, even in these difficult times, he will show "scrupulous respect for civil rights and personal freedom."

Others are skeptical. "Viewed separately, some of the changes may not seem extreme," Michael Posner, executive director of the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, said. "But when you connect the dots, a different picture emerges...Too often the U.S. government's mode of operation since September 11 has been at odds with core American and international human rights principles."

Even some progressives say the government, while making some questionable moves, has been restrained in light of the enormity of the September 11 attacks. "There has been no repression of dissent comparable to the measures adopted by [John] Adams, Lincoln or Wilson," Paul Starr wrote in the American Prospect. "We have neither mass hysteria nor mass internment, and public officials have been quick to condemn discrimination against Muslims and Arab Americans."

And New York, despite the often raucous nature of the debate, has remained relatively tolerant of dissent. In fact, says civil liberties lawyer Norman Siegel, the war has boosted discussion and protest. "I always thought of New York as the town of the big mouths," Siegel said recently . "Post 9/11, pre the war, I wondered, 'where have all the big mouths gone?'...With the war in Iraq, there has been more coverage of dissent and demonstrations."

In general, says Joshua Brown, a certain tolerance usually, though not always, characterizes New York's approach to protest. Like it or not, Brown says, New Yorkers cannot help but be exposed to a wide range of opinions. "The fact of being exposed to a range of different perspectives doesn't mean you accept these opinions but you are aware they exist."

And so, even in an era of orange alerts and Patriot II, that willingness to listen, and the steady infusion of new ideas, may well keep New York one of the world capitals of dissent.

For more information

Defend America

(U.S. Department of Defense newsletter about the war on terrorism)

M27 Coalition

(supports direct action, including civil disobedience, against the war)

Not in Our Name

(opposes war and crackdown on civil liberties)

Students United for American at Columbia University

(supports the war)

United for Peace and Justice

(against the war)

New York City Council STATED MEETING - APRIL 9, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - APRIL 9, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"If the people in the gallery were at work or at school, you wouldn't be here booing us." – Councilmember Madeline Provenzano, who voted against a bill to allow education to count toward welfare to work requirements.

Meeting Summary:

On April 9, the New York City Council overrode four mayoral vetoes, passing laws that Mayor Michael Bloomberg opposed.

The first veto override was on legislation (Intro 93-A) that would allow welfare recipients to count GED and English language classes toward welfare to work requirements. The council argues that under the current requirements people are forced to quit school for low-paying, dead-end jobs.

Mayor Bloomberg criticized the council, calling the bill "a giant step backwards in welfare reform" and promising to fight the measure in court.

"The council has chosen to turn back the clock on welfare reform, reviving a dated, discredited policy that we long ago learned was a failure," the mayor said in a statement. "Worst of all, what the council did today is a tremendous disservice to the very people it claims to be helping."

The council passed the bill into law by a vote of 46 to 5, with substantially more than the 34 votes need to override a veto.

Three Republican council members – James Oddo, Andrew Lanza, and Dennis Gallagher – and two Democrats – Peter Vallone, Jr. and Madeline Provenzano – sided with the mayor and were booed by members of the audience who came in support of the bill.

When voting against the measure, Bronx Councilmember Madeline Provenzano turned to the balcony full of advocates and made a remark. The microphone on her podium was turned off at the time and her statement was inaudible to most of the council. According to several people and reporters sitting near Provenzano at the time, she said, "You people need to go get jobs, not school."

After the meeting, Provenzano denied using the phrases "you people" or saying that they "needed to go get jobs," only that she said, "If the people in the gallery were at work or at school, you wouldn't be here booing us."

"I never had the luxury of going anywhere for three or four hours," said Provenzano, who raised three children by herself after her husband died. "I was full time mother, full time working, full time school. I think that's the way it should be."

The three other veto overrides also passed by a wide margin.

A measure the council calls the School Accountability Act (Intro 215-A) would require the Department of Education to submit quarterly reports on the status of all capital projects. All 51 councilmembers - even the three Republicans - voted to override Mayor Bloomberg's veto.

Mayor Bloomberg said the reports would cost the city $500,000 a year. "Since so much of this information is already available to the City Council and is not even read...it is hard to imagine why, during a fiscal crisis, we need to use scarce resources to pay for more bureaucracy," the mayor said in a statement.

The two other mayoral veto overrides related to the issue of emergency contraception.

One bill (Intro 278-A) requires pharmacies that do not carry the drugs Preven or Plan B, which were both approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1997, to post signs indicating that they are not sold at that location. The council overrode the mayor's veto of Intro 278-A by a vote of 43 to 8. (Council members Avella, Felder, Gallagher, Jennings, Lanza, McMahon, Vallone, and Oddo voted with the mayor.)

The other bill (Intro 281-A) requires hospitals that contract with the city to inform rape victims that emergency contraception is available and to offer it if requested. The council overrode the mayor's veto on Intro 281-A by a vote of 47 to 4, with council members Felder, Gallagher, Lanza and Oddo supporting the mayor.

"These bills will significantly reduce the number of unintended pregnancies in the city and are especially important for victims of sexual assault or rape," said Councilmember Christine Quinn, one of the authors of the legislation.

The council also passed a new piece of legislation in preparation for tax season. The bill (Intro 383-A) requires tax-preparers to let New Yorkers know the interest they will be charged if they take their rebate as an immediate loan. These loans, often billed as "Rapid Refunds," can charge between 200 to 500 percent interest.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for April 30, 2003.

Â