New York City Council STATED MEETING - July 23, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - July 23, 2003

Meeting Summary:

Shooting at City Hall

New York City Councilmember James E. Davis was shot and killed at 2:08 p.m. on July 23, the victim of a gunman who opened fire inside the City Council chambers during the council's regularly scheduled meeting. Davis was shot by a political rival, Othniel Askew, who accompanied the council member to City Hall. Askew was shot by a plainclothes police officer and died later.

Askew, 31, reportedly entered City Hall as a guest with Davis and was able to bypass the metal detectors because he was with the council member. Askew and Davis met earlier in the day in Brooklyn then proceeded to City Hall, where Davis introduced Askew as a former rival turned friend. The two men went to the balcony before the beginning of the council meeting, where, according to police officials, Askew fired a 40-caliber handgun multiple times, killing Davis. A police officer on the floor of the council chambers then fired six shots at Askew, hitting him several times. Davis, a retired police officer, carries a handgun, but did not draw or fire his gun.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who was in his office at the time of the shooting, was unharmed.

Askew was planning on running for City Council against Davis this fall, had filed with the city's Campaign Finance Board, and had reportedly circulated petitions, but did not file them in time to get on the ballot. According to reports, Askew phoned the New York City Federal Bureau of Investigation office yesterday morning to report that Davis had been harassing him in connection with the upcoming primary election.

James Davis, 41, who was elected to Brooklyn's 35th district council seat in 2001, was a former police officer, and the chair of Stop the Violence, a non-profit organization, which he founded in 1990. Davis also fought against youth violence, child abuse, domestic violence and police brutality, winning widespread media attention for his efforts. In 1994, he helped stop the sale of "look-alike" toy guns following the shooting of two children by police officers who mistook their toys for real weapons. He also campaigned successfully to have MTV change its broadcasting policies, arguing that the network's former policies resulted in the broadcasting of excessively violent images and lyrics during the daytime. A graduate of Pace University, he also served as a Democratic district leader, working to register voters in neglected communities.

In an essay Davis wrote for Gotham Gazette, he recounted how he became politically involved: "One morning in 1983, I was in front of my house sitting in my mother's car. Suddenly, I was approached by two white police officers who accused me of stealing the car. The officers dragged me from the car at gunpoint, slammed my head and body repeatedly against the car and pointed their guns inches away from my head. I was handcuffed and taken to the police station. No charges were ever filed, but that day, I suffered not only bruises, but also the humiliation of false arrest. Since that day, I have tried to turn that experience into something positive."

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

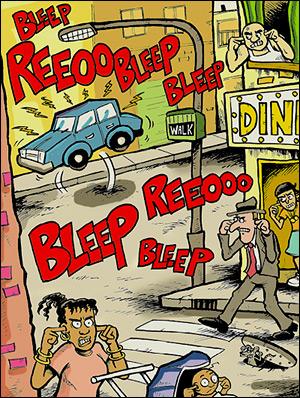

The Case Against Car Alarms

"A burglar alarm combines in its person all that is objectionable about a fire,

a riot, and a harem, and at the same time has none of the compensating advantages." So wrote Mark Twain in 1882.

"A burglar alarm combines in its person all that is objectionable about a fire,

a riot, and a harem, and at the same time has none of the compensating advantages." So wrote Mark Twain in 1882.

More than a century later, alarms have grown louder and migrated to cars parked in every New York neighborhood, and no one is any fonder of them. Councilmember Eva Moskowitz (D-Manhattan) says "the most frequent noise complaint" from her constituents is about car alarms. Now she and Councilmember John Liu (D-Queens) are each sponsoring a bill that promises to solve New York's car alarm problem.

Liu's bill, introduced in 2002 with nine co-sponsors, would ban the sale and installation of audible car alarms in New York City. Moskowitz's bill, introduced in April with fifteen co-sponsors, would go further, banning the sale, installation, and use of the alarms. Moskowitz also proposes a mechanism for citizens to report annoying alarms to the police, prompting a warning letter to the car owner.

It is clear that these bills have the full support of New Yorkers. In a survey conducted earlier this year by Transportation Alternatives (whose results are published as part of a report I co-wrote, Alarmingly Useless: The Case For Banning Car Alarms In New York City ), three-quarters of the 800 New Yorkers who responded said that car alarms interfered with their sleep; 90 percent said that alarms diminished their quality of life. Many spoke passionately: "This is one of the annoyances that rises to the attention even of life-long New Yorkers like me," one said, typically. "I don't hear fire engines, but I do, painfully, hear these car alarms -- while I'm sleeping, when I'm trying to read or think or just live. They're all useless, loud, and extremely disruptive."

And useless they are. The only unbiased study ever done on the subject -- one conducted by the insurance industry -- shows that car alarms do nothing to stop car theft.

But when a version of Liu's bill was introduced in the City Council in 1997, lobbyists for the car alarm manufacturers derailed it.

Not surprisingly, these manufacturers are once again trying to convince the City Council not to ban their product. At a recent council hearing on car alarms, Directed Electronics spokesman K. C. Bean said, "The proof that our systems work is exhibited in the fact that since 1993, annualized vehicle theft in New York City has fallen by 76 percent." Of course, crime is down across the board; during the same period, New York City's murder rate dropped by 70 percent, and robberies by 68 percent. Car theft rates would probably have dropped dramatically too, with or without alarms. But this statistic was the only "proof" any of the manufacturers were able to cite.

At that same hearing, the New York Police Department also decided to oppose the car alarm ban. Its reasoning was hardly better than Bean's. Assistant Commissioner Susan Petito said New York should permit car alarms because "we can't know for sure whether audible alarms deter car thefts." Apparently, the NYPD has never seen the insurance data. When pressed, Petito admitted that the department has no evidence that alarms work, keeps no statistics on the arrests (if any) that car alarms have led to, and knows that police officers themselves usually ignore the alarms.

In fact, the department put out a booklet in 1994, "Police Strategy No. 5," of which the assistant commissioner seemed to be unaware. The police pamphlet called car alarms an "annoying and sometimes unbearable disturbance for residents in their homes." They "frequently go off for no apparent reason." And as one of the "signs that no one cares," they "invite both further disorder and serious crime."

The truth is, there is no reason to allow car alarms to continue in New York City -- and many reasons to ban them.

CAR ALARMS ARE HARMFUL TO OUR HEALTH

A recent Cornell University study finds that traffic noise raises blood pressure, increases stress hormones, and leads to "learned helplessness" in schoolchildren. Many traffic sounds contribute to the problem, but car alarms, unpredictable and often exceeding 125 decibels, can be especially harmful. The World Health Organization warns that even for those who think they can "tune out" or ignore the noise, physical tests show otherwise. "There [are] increased levels of stress hormone and elevation of resting blood pressure."

Children bombarded with car alarm noise suffer even more. A noisy environment makes sleep and concentration difficult, and can interfere with language acquisition. Noise analyst Arline Bronzaft's famous study in a Manhattan elementary school found that children in classrooms facing noisy, elevated subway tracks read as much as one grade-level below their counterparts in quiet classrooms. Another study by psychologist Sheldon Cohen examined an apartment building overlooking the George Washington Bridge, and found that children living on lower, noisy floors did not read as well as those on the quieter, upper floors. The experts believe that children exposed to loud traffic noise learn to ignore sound cues, which makes it harder for them to pay attention in class.

Car alarms also contribute to a break-down in civility among neighbors. In a series of psychological studies beginning in the 1970s, researchers "accidentally" dropped books on the sidewalk and measured how often passersby offered to help pick them up. In normal conditions, 80 percent of the pedestrians offered help. With an 87 decibel lawnmower blaring nearby (about half the volume of an average car alarm), only 15 percent of passersby offered their assistance. Loud noise, as later research confirmed, makes people less attentive to the needs of their neighbors.

Perversely, then, alarms alienate the very neighbors that car owners depend upon to call the police when their alarms go off.

CAR ALARMS DON'T STOP THEFT

In 1997, the insurance industry's Highway Loss Data Institute looked at insurance claims data from 73 million vehicles, to see which devices could prevent theft. While new vehicle immobilizers cut theft rates in half, the study concludes that cars with alarms "show no overall reduction in theft losses" compared to cars without alarms. The alarms just don't work.

"An audible system is really just a noisemaker," explains General Motors spokesman Andrew Schreck, who notes that only eight percent of GM's light duty vehicles now have an alarm as standard equipment. "Most people, when they hear an alarm, they just walk the other way."

There are two main reasons that car alarms don't work. First, people know that the vast majority of blaring car alarms are false alarms, set off by passing trucks, electrical malfunctions, or nothing at all. So no one responds to them -- often, not even the car owners themselves. A recent survey by the Progressive Insurance Company found that fewer than one percent of respondents would call the cops upon hearing a car alarm. In 1992, Darrell Issa, the multimillionaire founder of car alarm manufacturer Directed Electronics (who now leads the recall drive against California Governor Gray Davis), told the New York City Council that an alarm is effective "only in areas where the sound causes the dispatch of the police or attracts the owner's attention." In New York City, this just doesn't happen.

Second, alarms are very easy to disable. About 80 percent of stolen cars are taken by professional car thieves, and they know how to deactivate an alarm in just a few seconds, according to police and criminologists. "No one has demonstrated that alarms are effective," says Rutgers criminology professor Michael Maxfield, now studying car theft for the state of New Jersey. "No one seriously recommends them as a serious protection against theft. They might help a small bit, but there's a good reason why actuarial data show no benefit [to having an alarm]."

How to get New York car owners to switch over to effective -- and quiet -- anti-theft devices like vehicle immobilizers, tracking systems, and silent pagers, which do not cost any more than noisy car alarms? The Council can pass a ban on the old, ineffective, and unbearably noisy ones. The two bills under consideration would, in fact, help everyone here: local installers, who will be hired to change cars over to silent security devices; car owners, who will benefit from better security and bigger insurance discounts; and the millions of New Yorkers who wish, once in a while, to get some sleep.

Aaron Friedman is founder of Silent Majority: Citizens Against Car Alarms, and is a consultant to Transportation Alternatives.

New York City Council STATED MEETING - June 25, 2003

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - June 25, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"It was like a hit team came down and shot up small businesses without a warning." - Councilmember Michael Nelson on a rash of tickets to business owners who put illegal information on their awnings.

Meeting Summary:

Responding to complaints that the city is issuing too many tickets, the New York City Council approved a six-month moratorium on citations to store and restaurant owners who violate the law with illegal awnings.

Under a law passed in 1961, store awnings can only include the name and address - no phone number, logos, or descriptions allowed - and the letters cannot be more than 12 inches tall.

The council estimates that 90 percent of the city's storeowners are in violation and wants time to update the law.

Business owners who violate the law can be fined up to $2,500 and complain they are being targeted in a ticket blitz to help balance the city's budget. (For more read the Summer of Summonses.) In the first three months of the year, 1,211 violations were filed, according to the city's Department of Buildings. In 2002, 1,736 violations were issued during the entire year.

The council passed the moratorium (Intro 305-A) by a vote of 47 to 1. Only Queens Councilmember Helen Sears voted against it.

On June 24, the council approved an increase in the personal income tax for the wealthiest New Yorkers. Individuals earning more than $100,000 a year and couples making more than $150,000 a year will see their income tax increase to 3.65 to 4.25 percent. Those making more than $500,000 a year will pay 4.45 percent.

The tax hike is part of a budget negotiated by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the State Legislature in May. As part of a $2.7 billion aid package from Albany, the city agreed to raise sales taxes, personal income taxes, and institute a surcharge on absentee landlords.

The vote was 46 to 3, with the council's three Republicans - James Oddo, Andrew Lanza, and Dennis Gallagher - voting "no."

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for June 27 when the council is expected to approve a new city budget. For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.