A New Executive Order: Don't Ask, Don't Tell

While walking back home from work, Chris Un was harassed by two men who shouted, threw soft drinks and threatened to hurt him. Un thought about calling the police, but remembered that a friend from the consulate had warned him about a new crackdown on undocumented immigrants.

"I was afraid that the police were going to arrest me instead," said Un, a former student who had overstayed his visa.

These kinds of fears were why the city had not allowed the police and city workers to question anyone's immigration status. But that changed in May when Mayor Michael Bloomberg issued Executive Order 34 allowing the city's agencies, including police, to report illegal immigrants to the federal government.

Un is among many of the 400,000 illegal aliens in New York who came to believe that the order was an anti-immigrant measure.

After months of intense pressure from immigrant advocacy groups and the City Council, Bloomberg finally issued a new executive order in September.

Executive Order 41, dubbed as "don't ask, don’t tell," replaces Executive Order 34 and prohibits city agencies from inquiring or disclosing immigration status of New Yorkers who come into contact with city government.

"This gives assurances to all law-abiding New Yorkers… that the confidentiality of information you give to the city will stay with the city," Bloomberg said.

Some argue that the mayor simply failed to clarify what Executive Order 34 was supposed to do, since similar policies have been successfully implemented with support from immigrants in other cities.

Designed to comply with the 1996 federal law, the language of Order 34 was vague enough that a literal reading of the order would allow police to make "sweeps of immigrants who are not suspected of any crime," attorney Scott Rosenberg told the Village Voice.

Until Order 34, every mayor since Ed Koch had followed a "don't tell" policy and didn't cooperate with the federal immigration agency. In 1996, Congress passed a law that said the city cannot forbid city workers from voluntarily reporting illegal aliens. Mayor Rudy Giuliani resisted but lost when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the federal law and ruled in 1999 that Koch's policy was illegal.

Though similar to Koch's order, city officials said, Order 41 does not violate federal law since it follows guidelines from the 1999 ruling by making confidential a larger class of information -- for example income tax records, sexual orientation, status as a victim of domestic violence -- not just immigration status.

Critics added that the mayor's change of heart comes at a time when he needs immigrant support, especially from the Hispanic community, to help boost his sinking job approval rating.

"Given the general erosion of his position in the opinion polls, Bloomberg really needs to have a strategy for rebuilding support in these constituencies," John Mollenkopf of the Center of Urban Research told the New York Times.

However, others are pleased with the new initiative and don't think that it matters whether the mayor has a political agenda. "What is really important is not the mayor's reasons … but the end result of his decision to amend the order," wrote columnist Albor Ruiz in the Daily News. "Bloomberg actually made [Executive Order 41] the strongest local confidentiality policy in the nation."

But as Bloomberg took steps to protect New York City's illegal alien population, Congress was taking another to toughen federal immigration law. This past July, Representative Charles Norwood of Georgia introduced the Clear Law Enforcement for Criminal Alien Removal (CLEAR) Act, which would allow local police to enforce federal civil immigration law. At the moment, local police can only enforce criminal immigration law. No one is quite sure how the CLEAR Act would affect Bloomberg's executive order.

An immigrant from Bangkok, Thailand, Chaleampon Ritthichai is the editor of The Citizen.

New York City Council STATED MEETING - September 30, 2003

New York City Council Stated Meeting Report

Every two weeks the New York City Council meets for its Stated Meeting to introduce and pass legislation. As a regular feature, Searchlight covers these meetings and posts a summary of the bills passed.

STATED MEETING - September 30, 2003

Quote of the Day:

"Does anyone know the score?" - City Council Speaker Gifford Miller inquiring about the afternoon playoff game between the New York Yankees and the Minnesota Twins. The meeting was brief so that the speaker could attend the game.

Meeting Summary:

The New York City Council marked the beginning of the Major League Baseball playoffs and the first game of the American League Division Series for the New York Yankees by passing a bill (Intro 482-A) that makes trespassing on the playing field of a professional sporting event a "Class A" misdemeanor.

The legislation stems from a series of incidents in which fans have run onto the field and assaulted coaches and umpires in Chicago. It only applies to professional sporting events, and college, high school, and recreational sports are exempt from the law. Those who violate the law could receive up to a year in prison and up to $1,000 in fines.

"This legislation protects not only participants on the field, but also those watching a sporting event, from lawlessness and disorder," said Speaker Gifford Miller. The bill passed by a vote of 42 to 1 (8 members were absent), with only Brooklyn Councilmember Charles Barron voting against it.

The council also unanimously passed a bill (Intro 195-A) to create a 15-member advisory board for the Taxi and Limousine Commission, consisting of drivers, members of the public, owners, organizations advocating for drivers, and agencies enforcing commission rules. The mayor and the council speaker will appoint the members and supporters hope that the board will be a constructive way to address taxi issues in the city.

"This is something that will bring a voice to many drivers who don't have a voice... and it improves the safety of the industry," said Washington Heights Councilmember Miguel Martinez, who once worked as a cab driver.

The City Council also passed a measure renaming 77 streets in the city, most for police officers and firefighters who died on September 11, 2001. Streets were also named for New Yorkers who died in combat in Iraq and for Celia Cruz, the salsa star.

The next Stated Meeting is scheduled for October 15.

For an archive of past meetings and council votes, visit Gotham Gazette's Searchlight.

Leaving New York

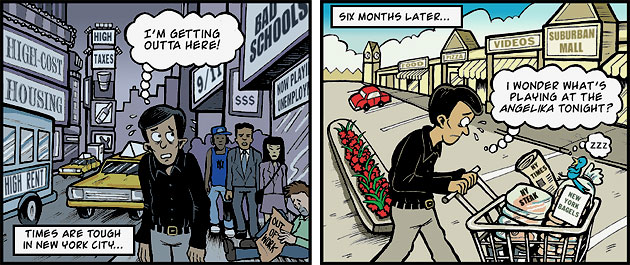

![]()

Why New Yorkers Are Leaving: The City Is Too Expensive by E.J. McMahon City Schools and Housing Are Inadequate by David Kallick New Yorkers Who Left: Rondrae Hunter A Frustrating Apartment Search Allison Woods Struggling with Strollers and Schools David Bassine Fear of Terrorism Stefan Kochi Bad for Business |

He had not planned to do this. But, after suffering through a season of tax increases, a subway fare hike, a stagnant economy and sundry other outrages, "what finally took me over the edge," he said, "was the act of going out and looking for an apartment." The best place he could find within his price range was on Fresh Pond Road in Queens. The floor slanted, and although the apartment had as a selling point the fact that it was close to the subway station, it turned out to be too close; he was afraid the noise would keep his baby awake.

To the Hunters, then, a main reason for leaving New York was the lack of affordable housing. For Allison Woods, another native New Yorker, it was the school system. Stefan Kochi, a businessman originally from Albania, blames the economy. David Bassine convinced his wife and two sons to leave because, he says, "I got scared after 9/11."

There is no question that individual New Yorkers are leaving the city. What is unclear is whether their exodus is anything unusual or alarming. It certainly seemed that way from a recent spate of articles and reports based on newly released data from the United States Census Bureau. For example, according to an analysis of this data for a report by the Center for an Urban Future on the economic challenges facing the city, some 150,000 Americans moved out of the five boroughs of New York City in the year after September 11th, 2001 - a 15 percent rise from the year before and 28 percent more than 1999.

But a closer look at these statistics reveals that, for some reason, the census bureau was counting only Americans, and not including any statistics about foreigners. Yet New York is now, and long has been, a magnet for immigration, and the influx of immigrants is likely to have more than made up for the outflow of residents. Indeed, there is some evidence that the population of the city is actually at an all-time high.

"People have always left New York in large numbers, and people have always arrived in New York in large numbers to replace them," said David Kallick, of the Fiscal Policy Institute. "I don't see anything significantly different about what's happening now."

Others believe, though, that the departure of long-time New Yorkers is both a problem in itself and a symptom of a city in trouble. Advocates and analysts have seized upon individual stories of fleeing New Yorkers to add new fuel to their ideological fires. On one side are those who say more government action - to build affordable housing, to improve the schools and to develop the economy - is needed to keep people here. (See essay by David Kallick.) On the other are those who argue that, in effect, less government action - especially lower taxes - will bring down the cost of living and keep the middle class within the five boroughs. (See essay by E.J. McMahon .)

GAINS AND LOSSES

For much of its history, the story of New York was one of ever-increasing population. This changed after World War II with the rise of the suburbs. The 1970s, when the fiscal crisis and a crime wave caused many people to lose faith in the city, saw the sharpest population decline in the city's history. That decade ended with 824,000 fewer New Yorkers than when it started. After relatively small gains in the 1980s, the population went through a period of sharp expansion during the 1990s boom, increasing by 685,000 between 1990 and 2000 to a record 8,008,278.

Even as the population grew, says Joseph Salvo, director of the Population Division of the New York City Department of City Planning, the city lost individuals to other parts of the region and elsewhere in the United States. But, unlike the situation in many other cities, these people were replaced by newcomers (largely foreign immigrants) and by newborns.

That continues, says Salvo, who says there is no evidence of an increase in people leaving the city. "In fact," he says, "we have evidence to the contrary" including a rise in the number of permits for new housing issued by the city in the past few years.

But the Center for an Urban Future disagrees. Jonathan Bowles, co-author of its recent report, has concluded that, since September 11th, 2001 in particular, people have been leaving in increasing numbers again and fewer newcomers are coming to replace them. Although that trend may be short-lived, Bowles said, "there's certainly a more negative attitude toward New York these days...The combination of service cuts, the economic crisis, the fiscal crisis, 9/11. It just doesn't seem as optimistic a place as it was a few years ago."

Bowles thinks there is reason to be concerned about the long run. As he writes in the report, if New York "retains only a short-run, narrowly based appeal for young people, who then leave later in life, it may find itself without a stable base of workers and entrepreneurs."

E.J. McMahon of the Manhattan Institute believes that the overall statistics, whether there has been a net loss or a net gain of population, are not as much the issue as the specifics of who is moving in and who is moving out. "The people who leave tend to have higher incomes than those who move in," he said. While McMahon does believe that the "vitality and dynamism of immigrants are very important to the city," he said that such immigrants usually demand more in the way of social services than those who move out. Their education, he said, also tends to be more expensive.

REASONS FOR LEAVING

9/11

David Bassine was one long-time New Yorker whose attitudes changed after the terror attacks. He moved to Connecticut in July 2002 after 12 years in the city. "With two kids, I just didn't want to be there. We were in the middle of the anthrax scare, and I was opening my mail with gloves and a mask on. I was nervous about taking my kids on the subway, and I just got frightened about the whole thing. I didn't want to put my children at risk."

Housing And The Schools

But in examining the reasons people left after September 11, most policy analysts describe the terrorist attack as a shock that simply exposed the city's existing problems. Bassine himself talks of the high cost of housing, and of the fact that his two sons were approaching the end of their elementary school years. They had attended a neighborhood public school that he and his wife were very happy with, but they worried about finding a nearby middle school of similar quality. School was also looming for Allison Woods when she moved from New York, pregnant with her second child. Woods, knowing that she could not afford New York private school tuition for two children and lacking faith in the public school system, moved to High Falls in upstate New York. There, she said, "we could use the public schools, or private schools that cost half...what they do in the city."

The Economy

Economically, New York had started to cool off even before the World Trade Center attacks. City Comptroller William Thompson released a report (in pdf format) last month stating that the city has been in recession for 10 consecutive quarters, dating back to the beginning of 2001.

Stefan Kochi, an Albanian immigrant living in Boston, moved to New York just in time to feel the effects of the economic slump. After opening a New York office for a Boston-based company that built websites for start-up firms in 1999, Kochi was forced to close the New York office in the summer of 2001. He planned to stay in the city but business associates changed his mind.

"Everybody was lukewarm about the economy in general," he said. "I thought if these people who I had planned to rely on...were not comfortable, the recession must be pretty bad."

Reluctantly, Kochi moved back to Boston, where he started a new company, which will now hire Bostonians of course instead of New Yorkers.

While the economy in much of the rest of the country shows some signs of recovery, New York's remains slow. Production gains have stayed below national levels, and the city continues to lose a larger percentage of its jobs than the country as a whole. In the second quarter of this year the city lost 10,600 jobs. Since January, 2001, the city has lost 241,500 jobs.

KEEPING PEOPLE HERE

Almost everyone agrees that the city's problems in housing, schools and the economy spur people to leave. What they disagree over is how to solve these problems.

Conservative policy analysts think high taxes worsen the economic situation. Most people do not specifically cite higher taxes as the reason for leaving, McMahon concedes, but the taxes create the conditions they do name, such as a lack of jobs and affordable housing. "There's no way to underestimate what the tax burden does to the cost of living here," he said. The solution, he believes, is cutting taxes and then making government more productive. He also calls for doing away with rent control, which he sees as a major barrier to the building of new housing in the city.

But those on the other side of the political spectrum see a need to maintain services and take a more active role in economic development. Bowles believes that recent hikes in the property and city income taxes were a reasonable way for the city to deal with its economic problems. "I think if the city was going to be drastically cutting funds for police or education, or other basic services, it probably would have made things even worse than they are right now," he said

The city's plan for economic development has suffered because of tunnel vision, focusing only on a few sectors, namely finance, insurance, and real estate, according to Bowles. He writes in the center's report that "the city should adopt a broader economic strategy to facilitate the creation of a better climate for growing small businesses, tap the potential of the boroughs outside Manhattan and put New York's human assets to better use."

New York is in a better position to do this now than in the past, largely because of gains through the 1990s that make more of New York a better place for people to live and businesses to develop. While housing and schooling remain problems that convince people to leave, said David Kallick of the Fiscal Policy Institute, "there have been periods when crime and safety and 'quality of life' issues were also big problems."

The declining crime rate and the virtual elimination of the most obvious quality of life violations (such as graffiti), as well as the overall development of many neighborhoods in the outer boroughs, have enabled many to stay in the city who might otherwise have left. So while almost twice as many people left Manhattan from July 2001 to July 2002 as did in 1999, many fled not to New Jersey or Long Island but to Brooklyn or Queens. They are no longer Manhattanites, but they remain New Yorkers.

To some extent, the ebbing and flowing of the city population is inevitable. "People come to the city looking for opportunity," said Salvo. When they achieve what they came here for, he said, they then leave to buy homes, pursue other opportunities or to retire - and are replaced by new people looking for opportunity. "It makes New York one of the most interesting places on earth." The key thing, said Salvo, is that those who leave are replaced.

For now, he maintains, that is still the case. Despite the bad schools, expensive apartments and high taxes, New York still exerts an irresistible draw. "I started to love this city from the first moment," said Jennifer Chert, a 23-year old Italian who spent several months living in New York earlier this year. In an effort to stay longer, Chert worked cleaning dog cages at a pet shop in Queens. "Obviously it was not a great job," she said. "But to stay I think I would have cleaned all the windows in the Empire State Building."

Meanwhile, after three months, Ron Hunter, while not exactly having second thoughts, is not entirely exulting in his new home. "Maryland is different, and I am having issues trying to get used to it. The slower pace of everything is hard to adjust to. Compared to New York, anything is slow, but this is really slow."