Understanding the Labyrinth: New York's Ballot Access Laws

Just how hard is it to get on New York's ballot? Go here to Play Bump the Birds, Gotham Gazette's new ballot access game and find out. Are you smart enough to get on the ballot - and tough enough to stay there?

If you have attended a street fair, shopped at a green market or even walked along a city street, you have undoubtedly seen them smiling, holding clipboards, asking for a moment of your time to please sign their petition. All three citywide offices, including mayor, the five borough presidencies and all 51 City Council seats are officially up for grabs this year, and candidates have been busy collecting signatures for petitions needed to get on the ballot.

Only 10 months ago, New Yorkers expected a far more frenzied political landscape, since all the citywide officials, four of the borough presidents and 32 City Council members were about to be forced from their office by term limits. Then, in October, the City Council and the mayor decided to give themselves more time in office, extending the number of consecutive terms they could serve from two to three. Many candidates were waiting, hoping to run for the open seats of council members who would have been term limited, but now only eight council districts will see completely open races with the incumbent not running for re-election. Most incumbent council members will be running to represent their districts for one more term, as will all the borough presidents -- shrinking the pool of choices for voters. Although most of the current office holders face challengers, the incumbents will go into those contests with a clear advantage.

To learn about getting on the ballot read "Getting on the Ballot in Other Cities."

Another factor has historically narrowed the pool of competition even further: New York's cumbersome ballot requirements. New York is one of a handful of states that still requires all candidates -- incumbents and challengers -- to file petitions with voter signatures to secure a place on the ballot. Those petitions have to comply with a complicated list of requirements for the signatures to be considered valid.

This has turned the whole petition process into a political blood sport. Candidates with experienced election lawyers can bump many of their rivals off the ballot by challenging the validity of their opponents' petition signatures, disqualifying the signatures from the candidates' total signature count. These errors can include unclear handwriting, or the absence of a zip code or borough.

The lengthy and complicated rules have created a system that hinders healthy competition, according to candidates, voters, good government groups and even some election lawyers, who make their living by knowing these intricate ballot access laws. They use them to help candidates stay on the ballot and even kick off the competition.

A Guide to New York's Ballot Access Laws

New York's notoriously cumbersome election laws were created in the late 1800s to democratize the election process. Up until then, party leaders controlled which candidates were placed on the ballot. However, today's petitioning requirements ensure that only those candidates with huge campaign war chests or party backing have the wherewithal to get on the ballot -- and stay there.

Here's a nuts and bolts synopsis of New York's ballot access process from the New York City perspective:

In order to get on the New York City primary election ballot this year, candidates could begin collecting signatures for their designating petitions on June 9 -- 37 days before the last day to turn in designating petitions for the primary election

The law is very specific about how many signatures candidates must collect. They have to get 5 percent of the enrolled voters of the political party in the political unit covered by the office -- council district, borough or the entire city -- or the specific numbers enumerated in the state's Election Law, whichever is less. For a candidate for City Council, that number is 900 signatures, but as a cushion against petition challenges, the rule of thumb is to obtain at least three times the legal minimum.

The candidates also must figure out is who is eligible to sign the petitions and who can collect the signatures. While only registered voters who are members of the candidate's political party and reside in the district in question can sign the petition, any registered voter who is a member of the candidate's political party and lives in New York City can collect signatures. Voters are allowed to sign just one petition per office.

The candidate has approximately five weeks to collect all of the requisite signatures and file his or her designating petitions with the main city Board of Elections office between July 13 and 16, which complies with the state law requirement that designating petitions be filed between the tenth Monday and the ninth Thursday preceding the primary election.

That done, the challenge portion of the petitioning process begins. According to the board's rules, it conducts a prima facie "review [of] each cover sheet and petition to ensure compliance with the New York State Election Law." This marks the first round of challenges to the candidate's petition -- but definitely not the last. The law allows any voter registered who can vote for the candidate to file written objections with the Board of Elections challenging that candidate's designating petitions. Those challenges must be made within three days of the filing of the petitions.

Once challenges are filed, the board holds hearings to assess the validity of the challenges and issues a determination. In order to appeal the board's decision a person must commence an action in state Supreme Court, the lowest level court in New York's court system, "within 14 days after the last day to file a petition or within three business days after the board makes a determination regarding the invalidity of such petitions, whichever is later."

If the appeal involves a determination about whether a candidate's name will appear on the ballot or a voting machine, the Supreme Court, if possible, is supposed to issue a final order at least five weeks before the day of the election. Candidates can appeal such decisions.

A Ballot Access Case Study

The Feb. 24 nonpartisan special elections for City Council held earlier this year offer a classic example of how the state's ballot access laws can cause major headaches for voters and election officials. Running for the Staten Island seat vacated by now U.S. Rep. Michael McMahon, candidate John Tabacco was a target of aggressive challenges by the current council member, then opponent, Kenneth Mitchell.

Tabacco faced two separate challenges. Like all candidates running in nonpartisan elections, Tabacco had to select a symbol for his "party." He made the mistake of selecting a five-pointed star, the official ballot sign of the New York State Democratic Party, which contributed to his unstable ballot status.

The other challenge involved the board assessing the validity of his signatures. The board re-examined some of Tabacco's petition signatures and decided that many of the signatures he collected were invalid; therefore his total collection failed to meet the number needed to appear on the ballot. After much legal wrangling, the day before the election, the Appellate Division restored his name to the ballot.

In preparation for the election, the board had already sent the voting machines to the poll sites, without Tabacco's name listed. With the legal decision coming less than 24 hours before the polls were set to open, the board had to swiftly shift to conducting the election on paper.

These last minute changes can be costly to candidates and taxpayers alike. In Tabacco's case, he said the petition challenges claimed 75 percent of his time during the special election in February, leaving him little to no opportunity to fundraise and campaign. He eventually lost to Mitchell, coming in fourth.

Of the total $179,983 he spent on the campaign, Tabacco said, approximately 28 percent went for election lawyers, political consultants and campaign volunteers related to meeting the petition requirement and defending the signatures in the legal process. "It's a completely outrageous, disgusting process," Tabacco said

The lengthy back and forth that can sometimes happen with ballot disputes, does not just cost the candidates. In District 49, the expense of all the paper ballots with the last-minute changes was eventually passed on to taxpayers. After including the cost of transporting the unused machines to and from the poll sites, staff to coordinate the move, and the printing of paper ballots for all the voters, the Board of Elections spent $132,564 on this election. Over $50,000 of that went for paper ballots.

Insiders' Perspectives on Ballot Access

Another candidate who ran in a Feb. 24 special election, George Dixon, a long-time resident of East Elmhurst and a former member of Community Board 3, has a slightly different take than Tabacco about the petitioning process -- probably because he had an election lawyer and didn't spend as much time in court as Tabacco.

"The upside is that you get someone out there and recognized in the community. The downside is that there are various reasons why a signature may not be considered valid," he said, noting that signatures can be removed if a piece of required information is missing, like the date or the county of the voter. "When you challenge a community of signatures, you're not challenging the candidate, you're challenging the voter," Dixon said.

Jerry Goldfeder, an election lawyer at Stroock, Stroock and Lavan LLP who worked on Julissa Ferreras' campaign against Dixon and other candidates in the Queens special election, said that there are better systems than petitioning for getting a candidate on the ballot. "I've been a long-time advocate of abolishing the requirement that one needs petitions to get on the ballot," Goldfeder says. "There are other ways to show community support to become a candidate, such as the number of donations, or perhaps a filing fee."

Election lawyer Henry Berger, agreed. "The petitions' challenges in New York are one of the tactics used to discourage people from running for office," he said.

Some claim the city's nonpartisan special elections present even more burdensome signature requirements than regular elections because candidates have to rush to get the required number of signatures in a much shorter time period. If challenged, the time period to appeal and stay on the ballot is much shorter as well.

Reforming New York's Ballot Access Law

Proponents for changing the ballot access laws argue that, under the current system, candidates are required to collect too many signatures with too little time, a task that can be difficult if you do not have the support and resources of a political party behind you. They say that, in effect, these laws diminish voter choice by only leaving one or two names on a ballot and excluding community members who might be credible candidates, but are unable to raise the funds necessary to withstand aggressive ballot-bumping. Candidates whose signatures are challenged, have to spend time in hearings with the Board of Elections and in the courts, taking precious time away from increasing their name recognition and campaigning. Perhaps more importantly, it drains financial resources.

One recommendation for reforming the state's labyrinth ballot access laws calls for reducing the number of signature candidates needed to appear on the ballot. Good government advocates also argue that other broad changes to elections can create a more level playing field for new candidates. Proposals include nonpartisan elections, ranked voting, independent redistricting and public campaign financing. Getting the access laws changed, though, poses a real challenge. Whatever they may cost voters and the public, these laws also benefit incumbents who want to remain in office and stymie competitive elections. Given that, it's no wonder that these laws have not been reformed.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel and Andrea Senteno is the program associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Additional reporting for this article was provided by Alex Kane, an intern for Gotham Gazette.

Where Is New York's Lieutenant Governor?

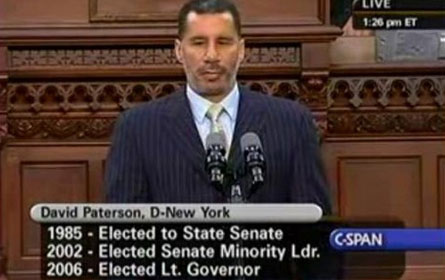

On March 17, 2008 when New Yorkers and the news media were focused on the resignation of Gov. Eliot Spitzer, few, and probably only hard-core political wonks, considered the effect Spitzer's resignation would have on the office of lieutenant governor since the then lieutenant governor, David Paterson, was about to become governor.

Now, over a year later, the lieutenant governor position remains vacant. Questions about the lieutenant governor's post have gained far more prominence given the very slim Democratic majority in the Senate. New York law allows the temporary president of the Senate, who is also the majority leader, to perform all of the duties of the lieutenant governor during the vacancy or inability, and Temporary President of the Senate and Majority Leader Malcolm Smith no doubt wishes that there were a Democratic lieutenant governor to give his Democratic caucus a much-needed tie-breaking vote. So does the temporary president of the senate get to vote twice if needed to break a tie vote? For obvious reasons Smith would love for the answer to that question to be a resounding YES.

The Conundrum of the Lieutenant Governor Vacancy

Unfortunately for Smith, however, while the New York State constitution empowers the lieutenant governor to act as the president of the Senate and also cast votes in that body, he will not be getting that extra Senate vote any time soon. That is because, the law does not specifically allow for the office to be permanently filled. Even worse, the law is about as confusing as can be with respect to how long the temporary president of the Senate fills this new dual role and how having two posts affects the temporary president's role as leader of the Senate chamber.

One would think that the current situation is only confusing because the situation is so unusual. Quite the contrary is the case, however, because lieutenant governor vacancies and their political consequence are old hat. At this point in the state's history, on nine separate occasions, a governor vacated that office and the lieutenant governor moved in to fill the vacancy.

This begs the question then: Why doesn't New York have a clearer and more concrete process for filling a vacancy in the office of lieutenant governor? Political realities of Albany politics aside, this convoluted process must be due at least in part to the state's complex and lengthy constitutional amendment process.

Passing a constitutional amendment in New York is a multi-step and multi-year process. In layman's terms, first the legislature has to introduce a bill proposing a constitutional amendment. Then that bill has to be reviewed by the state's attorney general to determine its effect on other sections of the constitution. After the attorney general approves the bill, then the Assembly and Senate have to pass the bill by majority vote before the end of the two-year legislative session. At the start of the new two-year legislative session after the succeeding general election, the bill passed during the previous session must age for three months before the legislature can vote on the constitutional amendment again. Assuming passage at this stage, the constitutional amendment must finally be approved by the voters.

In practice, this timeline means that even if legislators could decide on which process for filling the lieutenant governor vacancy they wanted to adopt for New York at this time, they would have to vote on the bill before the end of June 2010 and then again in 2010 or 2011 after the general election before putting it to the voters.

What Other States Do

If the Legislature takes the timing constraints seriously and gets down to the details, there are a few procedural options for how to fill this vacancy. According to a new report Filling Vacancies in the Office of Lieutenant Governor, published by Citizens Union, the nonprofit advocacy arm of Citizens Union Foundation, Gotham Gazette's publisher, 30 states specifically delineate a process for filling lieutenant governor vacancies.

Among those that have a process, the most common procedure - used by 14 states - is for the governor to appoint someone to the post who may or not be subject to some form of legislative confirmation. Ten of these 14 states, including California, Florida and Maryland, allow the governor to fill the appointment with a confirmation by a majority of both houses of the legislature. But some states like New Mexico, which amended its law in 2008, require that only the Senate confirm the governor's appointment.

Another seven states, such as Connecticut, Hawaii, Pennsylvania and South Carolina, either allow the temporary president of the Senate to automatically fill the vacancy, or make the temporary president serve in specifically limited capacities - like New York's process. At the other end of this spectrum, New York could adopt Alabama and New Jersey's practice of holding a special election to select the next lieutenant governor. The final option, which is used by two states - Rhode Island and Texas -- may be more in line with New York's tradition of appointing commissions or task forces to study issues. These states create a special senate committee that elects a replacement.

Currently pending in the New York's Legislature are at least six bills that adopt various forms of the processes for filling lieutenant governor vacancies used nationwide. The diversity of the proposals presents the Legislature with a variety of options, but in order to institute any change the governor and Legislature are going to have to act soon.

What Should New York Do and How to Get There

As any casual follower of Albany politics knows, change is slow, or at worst unlikely. So does that mean that New Yorkers are likely to be without full representation in the state capital in the form of a lieutenant governor? Unfortunately, the answer is yes. This is not only due to the potential for Albany inaction on this issue, but also because the timetable for passing a constitutional amendment means the legislature does not have enough time to act before New Yorkers elect a governor and lieutenant governor in 2010.

Even though it may be too late to change the current process for filling lieutenant governor vacancies before 2010, it does not mean the elected officials in Albany get a pass this time or that the fire is out and therefore Albany should do nothing. New Yorkers deserve full representation in Albany at all times, especially since the lieutenant governor is one of only four statewide elective offices, so elected officials have a responsibility to change the law to avoid this problem in the future - when, given New York's history, this ultimately will happen again.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette. Additional reporting for this article was provided by Jessica Lee, an intern for Citizens Union Foundation.

The Legislature Takes on Election Reform

The new Democratic hold on the State Legislature has made headlines for many things these past few months other than an increase in legislative activity or at least the appearance of one. Last year, good government advocates speculated that if Democrats won the State Senate and broke the decades long party split between the two houses, it would either be a new day in Albany or a test of the party's true commitment to reform.

While the Democrats have yet to receive a glowing review on the way they have handled some state matters, there is some indication that election reform is receiving increased attention. Even though the issue is widely seen as off radar during this economic crisis, there are currently over 50 bills in the Senate to amend election law. The Assembly has over 170 bills. A number of these measures -- some of them small -- could improve elections for New Yorkers.

Changes Big and Small

While it still seems unlikely that New York voters will be able to vote the weekend before an election, register and vote on the same day, or even sign up for an absentee ballot online anytime soon, some election legislation has jumpstarted the discussion. There are at least five different bills in the Senate and Assembly on early voting alone, and more on the implementation of Election Day registration, universal registration (where the government is responsible for keeping a list of eligible voters) and rules to amend the special election process.

Voting advocates have been pushing for changes like these for years. They argue that by making voting more convenient and by increasing opportunity and access to the polls, New York can increase its dismal voter participation record, which remains one of the lowest in the nation. Other states, such as Wisconsin and Minnesota who have programs like Election Day registration and early voting, are among those that boast some of the highest voter participation rates in the country. To remove some of the barriers to voting in New York's primary elections, a bill was introduced to shorten the lead time period for voters to change their party enrollment from the current requirement, which requires voters change party enrollment the previous year.

However, election reform is more than big changes, say voting advocates. It is also about the minor details that can make elections more transparent, accountable and secure. Recently, the Senate passed legislation that would count absentee ballots which were filled out in the correct poll site but at the wrong poll table. A long-held practice in many places, it is rooted in a court decision from 2005 (Panio v. Sunderland) that states being in the "right church, wrong pew" should not disqualify a citizen's ballot. The bill's sponsors also hope this measure would ensure that voters who receive an incorrect affidavit ballot, perhaps due to pollworker error, would still be able to cast a valid vote. It is now in the Assembly election law committee.

This proposed legislation seems to cover every aspect of elections. The bills target a wide range of problems, attempting to address long-standing issues with the state's administration of elections and even party politics.

One bill, for example, aims to require primaries for any special election to fill a vacancy in the State Legislature. Currently party leaders convene to select the official party backed candidate in a special election.

To address problems that have plagued poll site location, one bill would require all poll sites be handicap accessible according to the Americans with Disabilities Act. Another bill attempts to establish that no school serve as a polling place. In contrast, several voting advocates have argued that schools should be closed on Election Day so they can be used without compromising students' safety. And yes, there is legislation for that too.

Making Bills Law

Many have suggested that the good government platform -- including some election issues -- could make some real progress now that Democrats control both the Assembly and Senate. Other advocates, though, are quick to caution that the Democrats' true priorities will take shape as they settle into their fragile and newfound leadership role, and that pushing good government issues could still be an uphill battle.

Once bills pass through the appropriate committees in each house, they have to be voted on by the Assembly and Senate. It is widely speculated that the Assembly approved a number of reform bills in previous years knowing their passage in the State Senate would never come. With one-party control, both houses are likely to reevaluate their agendas, and issues that once sailed through the Assembly could encounter more opposition there. In addition, bills that pass the Election Committee in the Senate could meet a different fate on the Senate floor, especially since Democrats hold such a delicate majority.

A State Senate announcement this month that it would begin hearings across the state on election reform, though, gave advocates some cause for optimism. Sen. Joseph Addabbo, in the prepared statement, said, "We will address election issues with a deliberate approach, with hearings on voter registration, absentee ballots, election day and voting issues, Board of Elections oversight, new voting machines and other related matters."

Voting advocates hope these hearings will offer an opportunity to move the ball forward on many of the issues they have been pushing for. Aimee Allaud, elections specialist for the state League of Women Voters, said the hearings will "bring new opportunities for voters to speak to these issues which affect us every time we vote. New York needs to make additional progress in assisting all eligible voters to exercise the franchise."

Andrea Senteno is Program Associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.