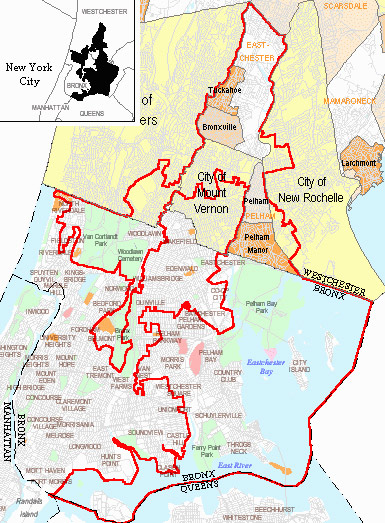

Bronx Senate District 34: Klein Goes for Three

Jeffrey Klein is finishing his second term representing this district that includes part of the Bronx and Westchester. Klein, who was then a member of the State Assembly, won the office in a hotly contested race in 2004 after the longtime incumbent, Guy Velella pled guilty to taking bribes.

In Klein's bid for a third term, he faces Daniel Fasolino, a retired police officer who has also been a real estate broker and homebuilder. In an interview with the Journal News, Klein said his key priorities included property tax relief and cutting spending to reflect the state's straitened economic circumstances. Fasolino cited his key concern as "the tax situation."

According to his 32-Day Pre General filing, Klein raised more than $48,000 in the reporting period and had almost $756,000 on hand. Figures for Fasolino were not available.

Tracking Building Inspectors

The inspectors are now under inspection. As of Oct. 1, the New York City Buildings Department began tracking its inspectors with Global Positioning System technology via their cell phones. Supervisors can see where the inspectors are at any given time, pull up archives of where they were the day before and even watch their minute-by-minute movement -- all they need is Internet access and a password.

The department's move faces opposition from the Allied Building Inspectors Union. The friction stems mostly from what the union claims is a lack of information about how the system will work and how the department will ensure that the technology does not follow inspectors during their time off.

The Department's Many Woes

The program comes amid building department efforts to cope with a year of controversy that, among other reforms, resulted in the resignation of former Commissioner Patricia Lancaster last year. The latest scandal came last week when six inspectors were arrested for bribery, and prosecutors accused the Luchese crime family of infiltrating the department.

Over the past five years, the Buildings Department has seen at least one bribery incident every year. Often inspectors themselves reported the bribe attempt to the Department of Investigations, which then worked with buildings to arrest the briber.

Tracking will certainly not solve all the department's problems. Knowing the location of an inspector does not immediately reveal wrongdoing in cases like bribery, said buildings department's spokesperson Tony Sclafani.

"This is one step to ensure integrity, but it's obviously -- it's not going to be the catch-all," said Sclafani.

Tracking Offenses

The Department of Investigation has worked closely with the Buildings Department on a number of cases in which GPS tracking would have indicated inspectors were not where they were supposed to be.

Following the crane collapse in March 2008 that killed seven people, the city arrested building inspector Edward Marquette. Marquette had allegedly falsified his inspection of the site 11 days earlier. Another inspection was conducted the day before the accident.

A press release on the investigative report published this past March states that the investigators "found that the DOB crane inspection and permitting protocols would not have identified the rigging errors that caused the collapse."

GPS would have sent warning signals about an elevator inspector who was on the payroll of the Buildings Department as an inspector and of the Metropolitan Transit Authority as an elevator maintenance supervisor. On his timesheets, he claimed to have worked for both departments simultaneously.

In a statement on the arrest, then Commissioner-designate Robert LiMandri promised to begin using GPS technology to ensure inspectors arrived at their sites. Even without GPS, though, the department's Office of Internal Audits and Discipline picked up on the discrepancies, which resulted in an investigation and the inspector's arrest.

Of the GPS program, the investigation department emailed this statement on Sept. 25: "DOI is supportive of any measure that improves supervision and strengthens integrity, accountability and safety for city inspectors." Neither of the departments addressed specific inquiries about whether the Department of Investigation will have access to the GPS software or records in the event of an investigation.

A Trend to Track

The department's revamping efforts have resulted in a dozen new laws, more money for oversight programs and reorganization of leadership. So why make the extra effort to monitor inspectors even more closely? Sclafani said the three main goals were "integrity, efficiency and safety."

President of Local 211 of The Allied Building Inspectors Union, Joseph Corso, disagreed. "Public perception. Sounds good," said Corso. "That's what they're doing. They're placating the public."

Other city governments that have instituted similar programs also have faced resistance. In Massachusetts in 2006, the public safety commissioner suspended 20 inspectors who refused to accept phones that had the GPS capability needed for tracking. Here in New York, the GPS technology can be activated on existing phones,

Inspectors in Bridgeport, Conn., were fired after the fire department secretly placed GPS tracking devices in their government vehicles and found inspectors using the cars for personal use. The inspectors went to court to argue that the devices were illegal according to state law. A judge rejected their argument.

New York City has its own experience tracking government employees. The Fire Department has Automatic Vehicle Locators in all of the city's fire trucks and ambulances. Fire department spokesman Steve Ritea said that the system allows the dispatchers to send the closest vehicle to the scene of a fire or other emergency.

The Buildings Department, though, will track people, not vehicles. It has signed up to use Telenav Track, a product of Telenav designed to follow the movement of employees who work outside the office. The product's website advertises that employers "get more from your mobile workers" with minute-to-minute tracking to "keep your finger on the pulse" and alerts on when workers enter or exit a certain location.

Sclafani said that the technology would correspond with the route schedule inspectors receive at the beginning of each shift. A supervisor can sit at any computer with Internet and look up the location of his unit's workers at that moment. The supervisor also can follow them from inspection to inspection or look at past routes to see whether or not they correspond to the schedule they were given. No one can access the information without the correct username and password.

The department publicly announced the plan Aug. 28 and began implementing it two days later.

Corso said the city should have provided the union with more information than it did and might file a lawsuit over the tracking.

Although the union knew the department had been considering the program for a while, the inspectors did not receive word of its implementation until the day before the public announcement -- three days before the city started using the software with its first 10 workers. The union did not know who those 10 workers were.

To date, Corso says he has not received documentation from the department about how the software works and what the actual plans entail. He said he had two face-to-face meetings with city officials, with few results.

Sclafani said that the union was "well-informed as to the particulars of the program."

If Local 211 does not receive adequate documentation "in the very near future," Corso said that the union would take legal action, a process that starts with the federal Labor Relations Board.

The union, Corso said, wants to ensure that the workers are not tracked past designated work hours, especially since a given inspection does not have a specific ending time. There is, for example, no set time for an inspector to go on lunch break. Because workers must keep their phones on 24 hours a day for emergency purposes, Corso is also concerned the software could track the inspectors after working hours. A sales representative from Telenav said turning off cell phones deactivates the tracking device.

Sclafani said that the technology was activated and de-activated according to the inspectors' schedules. "The software is sophisticated enough where we're only tracking them on duty," he said.

Corso dismissed the tracking program as unnecessary since the Buildings Department has people ensuring that workers are on site, including unit supervisors and the Department of Investigations. People who think it is the "norm" for inspectors to avoid certain stops on their scheduled route "just don't know the system," he said.

The tracking system could do more than upset current workers, Corso said. He worries that it will deter people becoming inspectors, a sobering prospect for an agency that already has a hard time recruiting new people

The inspectors' starting salary of $49,000, said Corso, is less than they could receive in the private sector. The idea of being tracked on the job, said Corso, would present "another stumbling block."

A Heartbeat Away -- But What is the Public Advocate?

Do you know what the public advocate does and that he or she is next in line to succeed the mayor? With New Yorkers set to vote in Tuesday's primary for many city offices, including public advocate, NY1 surveyed New Yorkers and found that most respondents not only did not know who the public advocate is or what the public advocate does, but also had no idea who is running for the office. With that in mind, here's a short primer on the origin and role of this official and the continuing discussion about the utility of this position.

When Did New York City Even Get a Public Advocate?

The position of public advocate originated in 1831 way back when the city was still five separate boroughs, according to a 1998 New York Law School Law Review article co-written by Laurel Eisner and former Public Advocate Mark Green, who is seeking the office again. It was not called the public advocate then, but even as president of the Board of Alderman -- a legislative body representing the borough of New York and portions of the Bronx -- the position was next in line to the mayor. This job was converted into that of City Council president in 1936 -- still a heartbeat away from the mayor in the event of vacancy, disability or other absence from office and empowered to preside over the Council.

The council president had a very limited role in government. During the 1975 charter revision debate, according to Green's article, it was noted that, although the office had no real administrative authority over the delivery of city services, was not a member of the executive branch and had a very narrow role in the council, it served an important function as a "critic at large." After debating whether to eliminate the office -- the first of many conversations about its role and utility of the office -- the 1975 commission instead decided to empower the council president through "a new, quasi-ombudsman role." The term ombudsperson derives from the Swedish word for "go between" or someone who would "protect individuals against the excesses of bureaucracy."

Despite these new ombudsperson powers, the council presidency still was pretty limited in its capacity -- lacking the ability to pursue individual complaints and the enforcement tools to ensure it could actually, not just theoretically, oversee or review city agencies. With this as a backdrop, the 1989 charter revision commission again revisited the issue of the role of the council president. Some commission members proposed eliminating the office, some said keep it, and some presented a new option that is still being debated until this day -- creating an appointed ombudsperson position.

Yet again the council president's role was saved from the hatchet -- this time because Commission Chairman Fredrick A.O. Schwarz argued that the role brought balance to city government by "concentrating on the service implications of the programs" implemented by the mayor.

The 1989 charter commission gave the office new responsibilities that created a bit of a several-headed monster -- one part legislator as presiding officer of the council, one part executive as first in line to succeed to the mayoralty, one part "charter cop" through the ombudsperson role and one part pension trustee for the city's Employees' Retirement System. It also gave the office power to appoint a member of the City Planning Commission, among other appointment responsibilities.

Today, the public advocate's legislative role allows him or her to be an ex officio member of all council committees and to introduce legislation, but not to vote. The ombudsperson role, which was substantially bolstered in 1989, empowers the public advocate to address individual grievances, deal with citywide problems, evaluate the performance of city agencies and "monitor public information service complaints of city agencies."

Despite the substantial increase in the council president's authority, only four years later in 1993, legislation was proposed in the city council to abolish the office of council president. This idea was again rejected in favor of simply changing the name of the office to public advocate to "reflect its charter roles and to dispel the impression that the holder exercised a predominant role in the City Council."

Fast forward to 2009, a municipal election year, and the discussion continues about keeping New York's public advocate. While the candidates vying to be the next public advocate give campaign speeches about what they would do to bolster the office's visibility and authority, at the other end of the spectrum Councilmember Simcha Felder from Brooklyn introduced a bill and issued a report in July 2009 -- proposing to get rid of the office altogether. "It is clear to me that given the services provided by the city's 59 community boards, five borough presidents, and numerous city, state, and federal elected officials, the office of the public advocate could easily be eliminated without a loss of service to city residents," Felder said. Felder's bill is currently pending in the Council's Governmental Operations Committee awaiting a hearing.

Other Places Have Ombudspersons Too

While electing a city ombudsperson may be unique to New York City, the tradition of a public official to empower ordinary citizens, especially those who have been marginalized, originated in the United States in Jamestown, New York. Many other cities and states have this function within their government structure. Portland, Ore., describes its ombudsperson, who is appointed by the city auditor and therefore independent from the mayor and the city council, as being able to assist the public with their complaints and concerns and promote higher standards of services and efficiency.

In Detroit the city ombudsperson is appointed by the city council, but is meant to be an independent government official to respond to citizen complaints against city agencies and government departments. Detroit's ombudsperson holds subpoena power so can retrieve documents and records necessary to conduct investigations -- a power that New York City's public advocate lacks. The current office holder, Durene Brown, claims success for being the first city official to change state law in Detroit -- passing a measure to include libraries as drug-free zones.

Other cities have appointed ombudspersons who focus on addressing complaints in specific areas, like police and law enforcement or senior citizen services, as is the case in Boise and Minneapolis, respectively. Finally, Los Angeles has an ombudsperson office that boasts ombudspersons to seven different city agencies, ranging from the Sheriff's Department to the Department of Social Services.

A Public Advocate's Perspective on the Matter

New York's current public advocate, Betsy Gotbaum, who has been in the office since 2001, said that although people are unfamiliar with the office and it has few resources -- it has a budget that is only "one two hundredth of 1 percent of the total city budget" -- she believes it helps thousands of everyday New Yorkers with their problems. In particular, she said, her office has focused on "improving services for often ignored populations."

Gotbaum disagreed that the services her office provides duplicates other services, citing the many calls the office receives as referrals from the city's 311 non-emergency hotline. She would like to se the 311 include a "direct link" to her office.

Moreover, her office has been able to help many citywide constituents by using a sophisticated computer-based tracking system that allows her and her staff to troubleshoot individual problems while tracking trends that may indicate citywide issues.

In addition, Gotbaum's policy staff, alone or in partnership with relevant advocacy groups, conducts research and issues reports spotlighting problems. These may or may not be accompanied by a press conference depending on whether the issue is something that her office believes the local media will cover. Because of "institutional limitations" and a difficult-to-engage press, Gotbaum said it has been difficult to get attention for the issues she believes are important. Like Gotbaum and the council presidents/public advocates before her, the next public advocate will have to learn to navigate these obstacles in order to be successful.

On Tuesday, many New York City voters may go to their poll sites and wonder who they should select as Public Advocate, why does it matter and whether they believe this office serves an important function. These are all important issues to consider on Primary Day and when the next charter revision commission or local legislation raises these questions again.

DeNora Getachew is the director of public policy and legislative counsel and Andrea Senteno is the program associate for Citizens Union Foundation, which publishes Gotham Gazette.