Stated Meeting -- Protecting

The City Council last week passed a bill that would protect "educational whistleblowers", setting up another conflict with Mayor Michael Bloomberg just two weeks after he rejected its plan to regulate pedicabs.

At its stated meeting, the council also passed laws that would extend benefits for family members of city workers who die in the line of duty, toughen prohibitions on video piracy, and protect the privacy of lobbyists' families.

EDUCATIONAL WHISTLEBLOWERS

The council whistleblower bill would extend protections to teachers, social workers, and others who report conduct that negatively affects a child's welfare.

Speaker Christine Quinn argued that there are holes in the current whistleblowers law that could leave some teachers unprotected from retaliation. She said that she was not aware of any case where a teacher had been punished for speaking out, but argued, "There is certainly evidence of teachers who have indicated that they have not come forward, because they feared what would happen."

Some outside the council charged that the bill as intentionally providing vague protections it as a way for critics – namely the teachers union – to snipe at the mayor's changes to the educational system.

The Daily News argued that state legislation already protects teachers who report mismanagement or abuse of authority, and said the law is "designed to sabotage, at the behest of the teachers union, Schools Chancellor Joel Klein's driver to bring accountability to the city's classrooms."

The United Federation of Teachers tried unsuccessfully to get a similar provision written into its contract last fall, said Bloomberg. He says he will veto the bill.

The bill passed by a vote of 43 to one, with Peter Vallone Jr. voting no, giving the council enough votes to override the veto.

FILM PIRACY

To protect the film industry, the council passed legislation (Intro 383) intended to cut down on film piracy. Over the last several years, city officials have taken steps to encourage the city's film industry, such as the creation of a film industry tax credit. As a result the industry is thriving, according to the council report that claims that the tax credit alone has generated 6,000 jobs and increased spending on film production by $450 million.

The illegal film industry also flourishes in the city, however. Between June 2004 and June 2005, 800,000 counterfeit DVDs and 700 DVD burners were seized in New York City.

Almost all bootleg movies are made by simply taping the screen in a movie theater, according to NBC-Universal, and half of these recordings are made in the New York area. This bill would make it illegal to operate film recording equipment in a movie theater, and violators would face six months in jail and fines of up to $5,000. It passed unanimously.

INCREASED BENEFITS FOR FAMILIES OF CITY WORKERS

Families of corrections and sanitation employees killed in the line of duty would continue to receive health benefits under another bill (499-a) passed by a unanimous vote, a benefit already extended to the families of police officers and firefighters.

The families of corrections and sanitation employees who are killed generally receive these benefits already, but the council has to amend the administrative code for each individual case. This bill would make that step unnecessary.

The families of two sanitation workers would benefit immediately, according to Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, the bill's primary sponsor.

Addabbo has previously introduced similar legislation that would apply to all city workers, but the idea languished due to concerns about the cost. He says he hopes to reach that goal "piece by piece," by protecting classes of city workers who are at the highest risk first.

LOBBYING AND PRIVACY

The council amended its recent changes to the lobbying laws, responding to concerns that the requirement that the addresses of lobbyists' children be published could endanger their safety. Watchdog groups consider information about donations from lobbyists' families essential, because these donation can serve as a way around contribution caps.

The change would not ease disclosure requirements, said Quinn; it would simply keep certain information private.

"You and the public will know that their child gave," she said in response to a reporter's question. "You won't know their child's address."

RESOLUTIONS: AMICUS BRIEFS AND LIBRARY WEEK

The council also passed two resolutions.

One (Res 803) would allow Quinn to file an amicus brief in the council's name in a lawsuit regarding a dispute over whether a landlord is allowed to receive city tax abatements while refusing to accept section-8 vouchers. Quinn believes that the landlord must accept the vouchers given to low-income residents to use for housing costs, and the Bloomberg administration agrees.

The three Republicans – Dennis Gallagher, Vincent Ignizio, and James Oddo – voted against the resolution.

The second resolution (Res 746), designated the week of April 15 to April 21 as "Library Week." It passed unanimously.

Â

A "Customer" Survey for the City

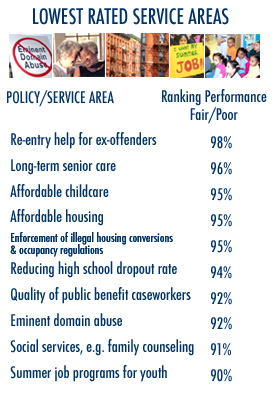

Is access to public transportation New York’s most important municipal service? Is the city’s poorest performance in the area of re-entry programs for former convicts? Is the public school system still faltering?

Yes, yes, and yes, a group of community leaders from the five boroughs told Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum at a forum on citizen satisfaction with municipal services. While these respondents are hardly a cross section of all New Yorkers, their comments on city services indicate what public officials might learn if they were to ask city residents Mayor Ed Koch’s signature question, “How’m I doin’?”

Who is the best judge of how well city government performs -- the bureaucracy responsible for providing service or the citizens who are supposed to benefit from municipal programs? Many experts agree that citizens are as qualified to evaluate city services than government itself, if not more. “The best way to encourage government performance is to measure it, and the best indicator of government performance is citizen satisfaction,” says the International City and County Management Association.

Still, in New York, most standard measures focus on government’s own definitions of success. The city measures how much money and staff time are put to use addressing problems, as well as the number and scope of new programs launched in response. It looks far less frequently at the actual results of programs or residents’ experiences with and attitudes toward those programs. While the Bloomberg administration has made great strides in performance assessment and reporting, New York City still does not regularly and systematically survey its residents’ perceptions and assessments of the services they receive.

Still, in New York, most standard measures focus on government’s own definitions of success. The city measures how much money and staff time are put to use addressing problems, as well as the number and scope of new programs launched in response. It looks far less frequently at the actual results of programs or residents’ experiences with and attitudes toward those programs. While the Bloomberg administration has made great strides in performance assessment and reporting, New York City still does not regularly and systematically survey its residents’ perceptions and assessments of the services they receive.

For example, the city knows that the number of calls to the 311 emergency hotline continues to rise. It also knows how quickly the calls were answered. But the government does not have information on how many of the 40 million callers to 311 have been satisfied with the city’s response to their problem, nor does it have information on how New Yorkers who do not call 311 feel about government services.

SURVEYING THE CITIZENS

Hundreds of U.S. municipalities, among them Phoenix, Miami-Dade County, Detroit, San Diego, San Jose, Austin, and Portland, Oregon use resident surveys. Gregg Van Ryzin, a scholar who follows municipal measurement trends closely, notes that the Government Accounting Standards Board, the International County Management Association and the National Academy of Public Administration have all championed customer surveys as an index of local government performance. Locally, a February 2002 “Policy Brief” by the New York City Independent Budget Office recommended that the city “identify and report on results that matter to the public and reflect the way the public sees and uses city services.” The office observed that “public accountability requires, in part, viewing an agency from the citizens’ perspective, understanding their expectations and collecting information that helps the public assess how well government is meeting those expectations.”

But effective, accurate and policy-relevant surveys are not easy to conduct. The challenge in New York is particularly daunting because of the sheer size of the city and the difficulty of distinguishing borough and neighborhood problems from those affecting the entire city. Surveys are expensive to design and write. Those drafting the survey must work to frame questions that reflect the public concerns – and not the thinking of whoever is writing the questions. A good survey must be tested before the final version is released into the field, and a statistically representative sample of respondents must be selected.

DESIGNING A SURVEY FOR NEW YORKERS

Despite such obstacles, New Yorkers may soon have a chance to grade their government. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum has begun an ambitious new program to gauge resident satisfaction. Working with experts from the Baruch College's School of Public Affairs, (including the two of us), she has assembled a Civic Leader Board to develop a questionnaire that will ultimately be circulated among a broadly representative sample of New Yorkers. Dubbed the Public Advocacy Project, the program will provide both an ongoing forum for community leaders and a regular gauge of residents’ satisfaction with key government services.

Despite such obstacles, New Yorkers may soon have a chance to grade their government. Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum has begun an ambitious new program to gauge resident satisfaction. Working with experts from the Baruch College's School of Public Affairs, (including the two of us), she has assembled a Civic Leader Board to develop a questionnaire that will ultimately be circulated among a broadly representative sample of New Yorkers. Dubbed the Public Advocacy Project, the program will provide both an ongoing forum for community leaders and a regular gauge of residents’ satisfaction with key government services.

Late last year, more than 60 civic leaders came to Baruch College to rate city services and to help provide topics for a future survey. Drawn from community organizations throughout the five boroughs, each leader brought a different perspective to the conversation. The structure was similar to the one employed in the summer of 2002 in the Civic Alliance’s “Listening to the City” program, in which thousands of New Yorkers gathered to express their views on the rebuilding of lower Manhattan after the 9/11 attacks.

At the forum, community leaders rated 100 city services as “extremely” “very” “somewhat” or “not that” important and on whether the service provided is “excellent,” “good,” “only fair” or “poor.” Each participant was provided with a handheld voting device. While voting was anonymous, the results of every vote were immediately visible on screen, providing immediate feedback for the participants. Within two hours, we had one roster of the services participants deemed most important, and another rating the city’s performance in each area (see tables).

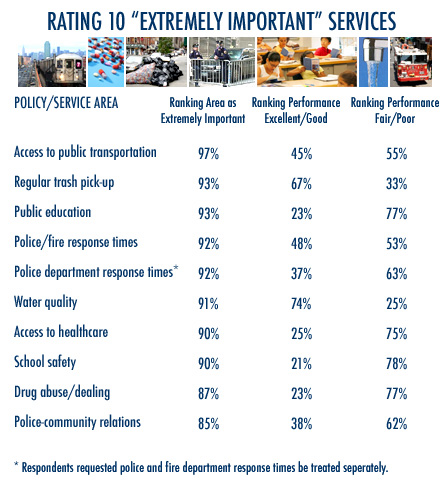

There was remarkable agreement on the top 10 service areas, with each being cited by at least 85 percent of the respondents. Access to public transportation ranked first, closely followed by regular trash pick up and public education.

Five focus groups then discussed the 10 areas in which city services were perceived to be most in need of repair. Along with helping former prisoners re-enter society, the groups cited long-term senior care, affordable childcare and affordable housing as needing improvement. For each topic, the groups provided a detailed breakdown of the problem; a sense of the city responses to those problems; positive elements of the city’s response; references to other responders, such as nonprofit organizations that have a good reputation for service/response in the area; and illustrations of the problem in specific neighborhoods.

Participants then came back into plenary session to hear what happened in the groups and to talk about next steps. They also had an opportunity to hear from the public advocate and to provide her with their reactions to the process.

LEARNING FROM COMMUNITY LEADERS

While the session provided valuable information about what some of New York’s most active citizens think of city services, the discussion’s core purpose was to generate and focus questions for a telephone survey of the general population. Telephone surveys cannot cover the full range of issues facing residents because they simply take too long to administer. It took a very dedicated, knowledgeable group of respondents two hours to move very quickly through our 100 topics; most surveys have to be completed within less than 25 minutes to maintain participation. By soliciting input from community leaders, we were able to identify issues that we had not thought about ourselves and frame follow-up questions around problems identified by the leaders, not by scholars or government officials.

We found several things that we had not expected. For example, the initial list of 100 topics had an item on “police/fire department response times.” The community leaders insisted that those two categories be separated on the public survey given their strong sense that police response times were inadequate, “particularly on weekends.” That concern emerged as one of the 10 most important issues facing the city.

Large categories, like “crime” need to be broken into smaller pieces to get a clearer idea of how to improve city services. For example, “safety from violent crime” was only 24th on the “extremely important” list, but three crime-related categories ranked in the top 10: police response times (fifth), drug abuse and drug dealing (ninth) and police-community relations (tenth). The discussion with community leaders will prompt an expanded treatment of crime in the broader survey.

We found several benefits to involving community leaders in the design of the survey. First, it creates a forum for civic leaders to express their opinions to public officials. Second, it enhances those leaders’ roles as advocates, strengthening community organizations and improving their ability to speak on behalf of the residents they serve. Third, the rich detail and extensive examples elicited in the focus groups provided a wealth of material for inclusion on surveys and illustrative stories about the way that residents live with problems and the city’s efforts to solve them. For example, one discussant said of police response times, “They’re fine Monday through Friday, but terrible on the weekends.” Many people talked about a lack of information -- on school bus schedules, on sanitation schedules, on street repair, and other vital services. These specific cases will help sharpen questions for the survey.

The final version of the survey will be fielded via telephone to a representative sample of New Yorkers in the fall of 2007. The findings will be circulated widely, discussed in depth with the community leaders, and repeated, with emphases on different issues, as the survey evolves in subsequent years.

These citizen surveys will provide a robust set of data with which to approach elected officials and the leaders of city agencies. It will offer an important corrective to the “complaints-only” data available from 311 and move New York closer to a genuine measure of service outcomes. City officials will finally know – from New Yorkers themselves – how they’re doin’.

Â

Broadband Haves and Have Nots

The last week of March saw two seemingly unrelated events that could affect the lives of poor people in New York City.

In one Mayor Michael Bloomberg outlined his plans for "Opportunity NYC,"which will provide cash incentives to low-income parents who make sure their children go to school, take their children to the doctor regularly and seek opportunities for employment and job training. The mayor hopes that such incentives will break the “cycle of poverty” that still traps many city families.

The second took place in the Bronx, where an advisory committee on expanding access to high-speed Internet access in New York City held its first hearing.

Bloomberg has stated repeatedly that tackling entrenched poverty is a core priority of his second and final term. His new opportunity program is a way to do that. And the mayor wants to increase Internet penetration throughout the city and the availability of “broadband” (high speed, wired or wireless access) connections. In this area, though, Bloomberg’s focus is on improving broadband access for the city’s businesses, especially those outside Manhattan. There is no doubt that this is critical; a recent report by the United States Department of Commerce documents economic benefits for communities that expand the level of broadband access

But the mayor has been less aggressive in trying to increase Internet access in disadvantaged communities. And many experts see changing that as one way to help reduce poverty on the harsh side of the digital divide. With improved access to high-speed Internet capabilities, children would enjoy enhanced educational opportunities and their parents could learn the skills necessary to thrive in an increasingly computer-based economy

THE NEW DIGITAL DIVIDE

Although broadband has become increasingly available for people of modest incomes, it has not reached those living at the lower end of the income scale. According to the most recent report by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, only 21 percent of households with an annual income of $30,000 or less had a broadband connection at home in 2006. On the other hand, 68 percent of households that earn over $75,000 had a home broadband connection.

While most businesses in Manhattan have a variety of options for high sped Internet options, businesses in the other four boroughs and residents all around the city are not so favored, according to a briefing paper prepared for the Bronx hearing. “Many of the businesses around the five boroughs have limited options for obtaining broadband and often find it impossible to access a reliable high-speed connection at all,” the paper said. And it continued, “Most residents have only one or two service providers from which to choose, and many are unable to afford the service.”

“Here in New York City, many underserved communities won't survive in this new information age without the technical knowledge many of us take for granted,” Council Speaker Christine Quinn said in a written statement before the hearing. “The bottom line is we need to use out-of-the box-thinking to ensure that today's technology is used to improve the future of New Yorkers.”

Improving access to broadband – and developing new ways to use it – could create jobs, improve schools and make the city safer, Gale Brewer, chair of the City Council technology committee, has said.

EXPANDING ACCESS

Many other American cities — from Philadelphia to Chicago to Houston to Los Angeles — have launched initiatives to increase broadband access for residents and visitors, as well as businesses. Meanwhile, New York has made modest enhancements to providing wireless (not necessarily broadband access) in city parks.

In an effort to expand broadband access for New Yorkers, City Council in 2005 passed Local Law 126, sponsored by Brewer, which established a “temporary advisory committee” to offer guidance to the mayor and City Council Speaker on “issues pertaining to access to broadband technologies within the city of New York” PDF). The City Council speaker would appoint seven members of the committee; the mayor would appoint eight. It was this committee that sponsored the Bronx hearing.

Four more such sessions, one in each borough, will be held this year. The goal for each hearing is to ascertain what New Yorkers believe is an “affordable” price for broadband access; how New Yorkers who already enjoy broadband use it; and how those without broadband access would use it if it were available to them.

The members of the Broadband Advisory Committee selected by the Council Speaker reflect Brewer’s belief in public investment to increase broadband access. They include Andrew Rasiej, who ran for public advocate in 2005 on a platform of radically increasing wireless access throughout New York City, and Neil Pariser, senior vice president of the South Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation, which has worked to close the digital divide in its corner of the City.

The mayoral appointees reflect a more business-centric approach to the issue. They include Howard Szarfarc, president of Time Warner Cable of New York and New Jersey, and Thomas Dunne, a vice president of Verizon New York. Szarfarc and Dunne also serve on the Mayor’s Telecommunications Policy Advisory Group and were among the people who in 2005 developed the mayor’s current telecommunications policy agenda, “Telecommunications and Economic Policy in New City: A Plan for Action.” With its clear focus on the business sector, this agenda does not address how to increase broadband access in disadvantaged communities.

Of course it makes sense to have business representation on the Broadband Advisory Committee. Unfortunately, this committee contains two groups that are working at cross-purposes. One side seeks government action to bridge the digital divide, while the other believes in an entrepreneurial approach.

It remains to be seen how much impact the Broadband Advisory Committee will have on public policy. Whatever happens, there is a strong case to be made for government investment to expand broadband access in poor communities. Even if “Opportunity NYC” succeeds beyond all expectations, a cash transfer program can only be so effective in a labor market that requires everyone to be comfortable with computer technology

Â