Musical Chairs: Shuffling Seats in City Government

March 31, 2008 -- This story was updated to reflect the latest campaign finance information.

Pink slips are on the horizon for more than 40 of the city's elected officials, and many are scrambling to keep them at a distance.

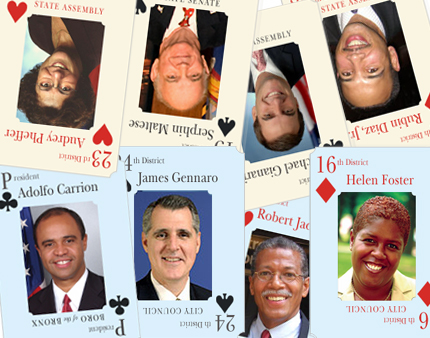

To do so, some officials are playing musical chairs, hoping to land seats -- possibly with larger constituencies -- when the music stops in November 2009. Others are shuffling their political decks a little sooner, fishing for possible employment in Albany, where the entire Senate and Assembly will be up for reelection this November (To find out what politicians wants what office, go to Gotham Gazette's "Who's Running for What," our new feature that allows you to check what candidates have already emerged for the 2009 races and where all those term-limited New York City officials may be heading).

All of this is possibly an unexpected consequence of the city's term-limit law -- passed twice by referendum in 1993 and 1996 -- which caps political positions in the city at two full terms. No such limit exists in Albany, where officials can -- and some do -- serve virtually for life.

Aimed at opening up the political process and weeding out career politicians, the city's term-limit law is forcing out about three quarters of the City Council next year, four out of the five borough presidents, the comptroller, public advocate and, of course, Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

While the public clearly passed term limits twice, some question whether the eight-year restrictions breed good policy and if it has bolstered the democratic process and public participation. Others wonder whether term limits perpetuate a system of backroom politics where a stagnant staff controls the reins in City Hall and politicians shuffle between the city and Albany or vice versa.

The Mass Exodus

Following the second referendum on term limits, City Hall saw a complete turnover. Officials who had been serving since the 1970s were kicked out of their offices and a barrage of new blood stormed city government in 2001. Outgoing officials predicted disastrous consequences. Incoming leaders said novel ideas would flourish.

Seven years later and some say a little wiser, there were no catastrophes or revolutions, leaving some advocates to question whether a push to extend term limits is merely the work of politicians who want to protect their jobs.

With another upheaval on the horizon, ask one of the 36 council members who are term limited how they feel about the policy, and you might be able to guess their answer.

"I feel like it should be 12 years," says Councilmember Gale Brewer, who is term limited in 2009. "I think eight years is not good for public service, not good for government, particularly not good for the nonprofit community," which needs to get to know their councilmember to provide quality service.

Question some of the members who still have another term, and some of them have a similar answer.

"I've always opposed term limits and believe that we really should go back and rethink term limits," said Councilmember Letitia James, who is not term limited until 2013. "What we are doing is creating a permanent government that consists of lobbyists and staff members."

Before her election as City Council speaker, Christine Quinn expressed support for expanding the term limit cap from two terms to three -- or eight years to 12 -- a position popular among the council members whose support she needed to become speaker in 2005. At the end of 2007, however, she retracted that position. According to a prepared statement, the speaker said: "I believe that overruling the will of New Yorkers -- who have voted twice in favor of term limits -- would be anti-democratic and anti-reform."

Quinn, by the way, is term limited and eyeing a run for mayor.

Any hope for a term-limit extension is lost, at least for now. And for some advocates, that's good.

"It's worse and disingenuous for the City Council to anoint themselves that they are more important than the voters," said Kenneth Moltner, founder of People to Stop a Self Serving Council -- a group that opposes the council's pursuit of an extension of term limits. "The voters may give them 12, if people want to give them 12. If the voters want to give them 16, give them 16."

The Expected Consequences

So far, 120 candidates have filed with the Campaign Finance Board for a 2009 candidacy. Many of those names are new to city politics. Even more officials are mulling a switch, looking at a New York City position from their perch in Albany (more of that later).

According to an analysis by Gotham Gazette, nearly 80 candidates, both declared and undeclared, do not currently hold public office and are looking toward a City Council run in 2009. Some of those candidates said they were more likely to run because they would not be challenged by an incumbent -- who would most likely have the backing of the city's powerful political machinery and the benefits of name recognition among his or her constituency.

"If there weren't term limits, I would have a much, much harder time getting my voice out," said City Council candidate Constantine Kavadas, who is running to replace John Liu in Queens. "Most of the attention always goes to the incumbent."

Bringing in new faces is one goal of the city's term-limit law. But so is eradicating government paralysis and so-called sedentary politics. If officials are constantly changing on eight or four-year cycles and the city is in a perpetual state of campaigning, the reasoning goes, officials will work that much harder to satisfy their constituents.

"The truth of the matter is there is a disconnect after a certain amount of time," said Terry Hinds, a declared candidate for 45th district, a seat currently held by term-limited Kendall Stewart. "You know you're going to win and you stop taking the concerns of the community as seriously as you should."

Another consequence of term limits is many races already have multiple candidates, forcing some to start their campaigns and their fundraising years before the actual election.

In district 19 in Queens, currently held by term limited councilmember turned mayoral candidate Tony Avella, four individuals have already declared their candidacy. One -- Paul Vallone, whose family has a history in Queens politics -- has already raised nearly $50,000 for the race, which is still almost 18 months away.

For citywide office, candidates, many of whom already hold public office, are chasing campaign cash at a far faster rate. Rep. Anthony Weiner, a mayoral candidate, has raised nearly $3.6 million for his 2009 bid, while Comptroller William Thompson has snagged $4.23 million for the same race.

According to a report by the city's Campaign Finance Board, net campaign contributions have surged, far surpassing what they were during a similar election cycle in 2001. Comparing the most recent campaign contribution filing period to a similar period in 2001, contributions have increased by 30 percent.

And the Not So Expected

Meanwhile some term-limited city officials are turning toward the State Legislature to continue their political careers, while some state officials look to snag a spot closer to home.

Already, nearly a dozen state officials have expressed or are rumored to have an interest in swapping out their state seat for one within New York City -- be it a spot in the City Council, a borough president position or city comptroller. For example, both Assembly members Michael Gianaris and Annette Robinson, who had left the council in 2001, are considering seats on the City Council, while Councilmembers James Gennaro and Charles Barron consider runs for state office.

Those attempting to make the switch from Albany to New York City argue that new blood and fresh ideas will come to both bodies, because the two places work very differently.

"The only same thing is that you're elected and that you have a constituency that you have to answer to," said Assemblywoman Audrey Pheffer, a candidate for Queens borough president.

This shuffle is certainly not unprecedented. Several members of the City Council, including Al Vann and Vincent Ignizio, served upstate before their current positions and vice versa. The trend is on the rise, though, as officials see the effects of term limits settling into City Hall.

"If that’s the case and all you're doing is musical chairs, that begs the question for the proponents of term limits: Have you really met your goal in terms of new leadership and new faces?" asked Assemblyman Ruben Diaz, Jr., a candidate for Bronx borough president.

Under the city's term-limit law, officials are forced out of office when they have served two full consecutive terms. But they are not barred from coming back. So, some former council members, officials who have already been the "victim" of term limits, are hoping for an encore in city government.

Tom Ognibene, a member of the City Council from 1992 to 2001, has declared his candidacy for a special election for Dennis Gallagher's seat in Queens. Gallagher recently resigned as part of plea deal on rape charges. Ognibene said his experience would help him deal with the daunting task of running in back-to-back elections, which is what occurs when an official resigns and special elections are called.

"If you don’t think people should come back and run again, then you don’t vote for them," said Ognibene, who questions the efficacy of term limits.

Swapping Seats and Switching Cities

Voters will have a full house come November 2009, with pairs from Albany or City Hall or even an ace newcomer making their way through the city's political hands. They will see some familiar faces -- and maybe some not so familiar ones.

So turn up the music and watch politicians attempt to swipe seats quickly before their time runs out and their song stops.

Â

One Person's Vandalism Is Another One's Art

Some call it a menace and an eyesore; others consider it an expression of their first amendment rights. Some of it has deep political meaning, while some is a word or two scribbled in permanent marker. And it can be found all over the city: on rooftops, bridges, the walls of dilapidated buildings.

Graffiti and street art have been highly controversial forms of expression in New York for decades, disdained by art snobs and building superintendents alike. The people who disparage it the most, however, are the city officials who clash with artists and taggers over their creations. Interestingly, this battle has done nothing to diminish street art's popularity. And now, some experts say, that popularity could do what city official couldn't: threaten the very essence of this ephemeral work.

The Eye of the Beholder

What exactly are street art and graffiti? For the graffiti artist, the goal is to "tag" the most places. Extra respect goes to those who manage to emblazon their trademarks on hard-to-reach spots, like billboards and the tops of high buildings. "If there are two graffiti artists, they will compete for fame. They might never meet, but they compete because they see each others names so much," said graffiti artist BG 183 of Tats Cru, a group of Bronx-based professional muralists.

Street art, on the other hand, usually has a political or social message and aims to encourage the viewer to think. Although like graffiti, street art is usually illegal, many consider it an alternative art form, valuable to the community at large.

"Street art will only hit certain areas - rich areas-- next to museums or galleries where people with money will see and notice it. They don't go to tunnels, or the side of a highway. They won't risk getting caught," said BG 183.

"Graffiti is used in the broader sense, and street art is sometimes classified as a subset of graffiti," said Dave Combs, co-creator of the street art "Peel Magazine." But, he continued, "some people who do graffiti have an element of their motive being destruction or vandalism. For the most part, people who do street art do it to create something new and meaningful and beautiful for the person viewing it."

The Official View

City Council, though, does not share that view or distinguish much between street art and graffiti. Some members claim both are a "public nuisance that degrades the quality of life in neighborhoods and communities across the city." To fight it, the council passed legislation in July, 2007, forbidding anyone under 21 years old to carry materials that might be construed as graffiti instruments. These include aerosol spray paint and broad-tipped indelible markers.

Some saw this as blatant age discrimination. The council rejected that claim, citing studies that show most people believes those aged 18 to 21 are disproportionately responsible for graffiti. Further, council members noted, there are other restrictions placed on those under 21, including not allowing them to purchase and consume alcohol.

The legislation is not the only movement toward a crackdown on graffiti. In October, Ellis Gallagher, a Brooklyn-based chalk artist, was arrested for drawing on the sidewalk in chalk, something he had been doing for years. Gallagher's arrest came only days after a summons was sent to a family in Park Slope, demanding that they remove the graffiti from their sidewalk or pay a fine of $300. The graffiti in question was also a chalk drawing, and the culprit was their six year-old daughter.

According to New York State penal law, graffiti is the "etching, painting, covering, drawing or otherwise placing of a mark upon public or private property with intent to damage such property," a police department spokesman told a Brooklyn Paper reporter. Given the impermanence of chalk drawings, they are a gray area in graffiti law but can still qualify as criminal mischief.

Into the Mainstream

While the city's effort to combat street continue, its acceptance seems to be growing in the cultural world -- perhaps to the detriment of "real street art. As its acceptance has grown, so has its proliferation.

There are books about the topic, and it is the main focus of magazines like "Overspray" and "Peel Magazine." Blogs, like The Wooster Collective and Streetsy display daily photos of street art from places all over the world.

Some artists have stopped limiting themselves using the streets as a canvas and begun using actual canvases, which then sell in galleries for thousands of dollars. Artists, such as Swoon, have been featured in world-renowned museums like the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum.

Certain major companies even commission graffiti artists to do advertisements for them. Tats Cru has been commissioned by several name-brand companies, including Snapple and Nike, to create advertisements. One of the artists, BG 183, stated "For us, the way I look at it, we're getting our name where regular artists can't go. We've been [featured] in museums, given lectures in college and traveled the world because of what we do. I can teach other graffiti artists, but I don't have to get caught and arrested. How many people can say that they're graffiti artists and make money from it?"

James Cade (professionally known as James Top), a former graffiti artist, currently teaches a 19 -week seminar at Hostos Community College in the Bronx entitled "Graffiti: The Art of Hip Hop." While many students were excited at the prospect of learning more about the taboo art form, Councilmember Peter Vallone claimed such a class would encourage vandalism. Vallone, a leading opponent of graffiti, has introduced various bills concerning street crime and vandalism, including one to double the penalties for anyone convicted of graffiti. Nonetheless, the class proceeded.

Artists vs. Street Art

As street art move more into the mainstream, some critics fear it will lose its essential edginess. "The Splasher," an unidentified person or group of people, splashed paint on a number of works by famous street artists from late 2006 to 2007. Next to the obliterated art they posted a wheat-pasted manifesto, whose awkward wording proclaimed street art to be a "fetishized action of banality" and that "representation is the most elemental form of alienation. Art by representation is no exception." Believing that street art had become too commercial and mainstream, the Splasher felt the only way to counter it was through destruction.

Although no one is certain of the Splasher's identity, 24-year-old James Cooper was arrested for lighting a stink bomb at the gallery opening of well-known street artist Shepard Fairey on June 27, 2007. The police and many street art enthusiasts suspect Cooper of taking part in the Splasher's doings. Two days after his arrest, a group gathered at another gallery opening and handed out 16-page booklets, entitled "If we did it, this is how it would've happened," which indirectly claimed responsibility for the stink bomb. The booklet's wording was similar to that of the Splasher and included the various manifestos that the Splasher had posted. There has been no sign of the group since.

"Street Art Blows" chooses pieces of street art it deems unworthy and places a sticker over them. It states in bold red letters "Keep Your Art to Yourself Next Time." The group's Web site elaborates on this idea, claiming that street art and graffiti have great potential that is being squandered by the masses. The site states: "Street art should be outside because it is necessary. Street art shouldn't be important because it is outside."

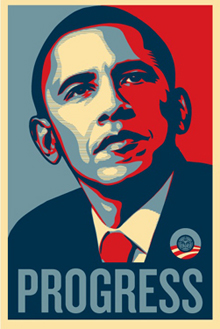

commissioned by the Obama Campaign

But Street Art's movement toward the mainstream shows no sign of abating. Consider the following: Shepard Fairey, one of the world's most influential street artists, was recently commissioned by presidential candidate Barack Obama to design campaign posters. The posters were sold at Barack Obama's online store and quickly sold out. In a letter to Fairey, Obama wrote: "I would like to thank you for the use of your talent in my campaign. The political messages involved in your work and encouraged Americans to believe that they can help change the status-quo."

As Combs stated, in reference to the poster: "There's a kind of validation in that."

Â

The Council and Congestion Pricing: Part II

If legislation has the support of Mayor Michael Bloomberg and City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, some City Hall observers say it is guaranteed to pass.

That is, unless that bill is a proposal to implement congestion pricing in Manhattan, charging drivers $8 to enter the borough below 60th Street during the workday.

In the next two weeks city and state officials might have to come down on either side of the congestion pricing cliff, and the City Council will be the first to step up to the ledge. Given the vast number of term limited officials eyeing the 2009 race and those looking to swap seats with state legislators later this year, some say officials might hesitate to take any politically risky position.

More than six months ago, Gotham Gazette polled all of the City Council's 51 members on the congestion pricing plan -- which then included a zone cordoned off at 86th Street. A vast majority declined to take a stand -- nearly half would not say whether they were declaratively for or against the transportation proposal.

Since then, other media organizations, including the New York Times, which conducted a survey earlier this month, have taken polls. And it seems the political tide is turning against the mayor.

What's Next

Both the State Legislature and the City Council must approve the recommendations of the Congestion Mitigation Commission , which came down with a congestion pricing proposal (See related story here ) in January.

Once a bill has been introduced in Albany and is assigned a bill number, the City Council must draft a state legislative request, otherwise known as a home rule message, urging the State Legislature to approve the measure. It is not required to hold a hearing on the message nor let the procedural legislation age -- meaning the council can introduce, approve in committee and OK the bill on the chamber floor all in one day, according to city officials.

Once Albany has the message in its hands, said city officials, then it can vote on the legislation.

All of this -- after multiple deadline revisions -- must be done by April 7 in order for the city to receive $354 million in federal funding that is slated to go toward mass transportation improvements.

With the clock ticking and renewed support from Albany with the endorsement of Gov. David Paterson, the City Council is likely to vote on congestion pricing within the next two weeks. The body has a meeting scheduled for this week, though officials said it's unlikely they would consider the matter then.

A Shifting Stance

Our August poll found that 13 members of the City Council, including Quinn, were in favor of the mayor's congestion pricing proposal and seven members leaned toward supporting it.

On the other hand, 10 members were against the proposal and one was leaning against. We found that 16 members were undecided.

Earlier this month, the New York Times found some members had made up or changed their minds: 12 were in favor, 20 opposed, 11 were undecided and 8 did not respond.

Comparing the two surveys, we found seven members who were undecided or leaning toward the proposal have now come out against it. That includes the entire Staten Island delegation and the chair of the Environmental Protection Committee James Gennaro.

And one member says the media still hasn't gotten his position right. Councilmember Alan Gerson, whose district is one of three that is entirely within the congestion pricing zone, says he is actually undecided, not against the measure, as both the Times and Gotham Gazette described him.

"I am undecided as it now stands," said Gerson. "I have had several very productive meetings with the Department of Transportation, the mayor's office and the speaker's office. We have raised several very legitimate concerns, relating to the Canal Street-Holland Tunnel corridor to bus management and issues of equity."

With officials coming out for or against the new proposal every day -- even its most stringent supporters have raised questions on fairness and equity -- congestion pricing seems to be a difficult issue to see in only two colors.

While it isn't black and white, members of the City Council could soon be faced with an up or down vote, which obviously does not come in shades of gray.

A Reason to Change or A Position Renewed

Much has changed since the summer. The congestion pricing zone has shrunk from 86th Street to 60th. The new proposal also eradicates a congestion pricing toll exemption for vehicles on the FDR Drive.

And more and more members have questioned whether it is fair for drivers from New Jersey to pay no more than the $8 toll already doled out to get through the Lincoln or Holland tunnels, while those in the outer boroughs are faced with a brand new fee.

Councilmember Simcha Felder, who told us he was for the plan in the summer, is now against it, said his Director of Communication Eric Kuo. The devil's in the details, said Kuo. Until Felder knows exactly where transportation funding would be directed, he is going to withhold support.

"At this point he's definitely against it, and there hasn’t been a plan to vote for," said Kuo.

Others credit the looming election with positions that have ebbed and flowed. (Though Felder is considering a run for city comptroller, his communications director said the upcoming election is not a factor in his decision.)

Councilmember Lewis Fidler, who is a staunch opponent of the plan, said some of his colleagues are watching what side potential political opponents may come down on. If a member knows his or her opponent in an upcoming State Senate race opposes congestion pricing, he or she is unlikely to vote in contrast to that position to avoid political vulnerability, he said.

"The fact that we are voting first, you can't avoid it," said Fidler. "You can't take the politics out of this unfortunately."

A Compromise Here and There

Given the authority and power behind the Bloomberg administration, some city officials have confirmed that council members might wait to see what they could get for their districts before they take a firm position on congestion pricing.

The congestion pricing funding will be geared toward mass transportation improvements, which could primarily be outlined in the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's capital plan. But because the authority's capital plan is grossly underfunded and projects are revised every year, some officials say promises on certain projects, from increased ferry service to increased service on the G, are not set in stone. A member could be basing their vote on an empty pledge, officials said.

But whether the vote is for politics or premise, city officials say congestion pricing will likely go down as the most divided vote in the history of the City Council -- which is usually characterized as a rubber stamp of the mayor.

"I think the mayor, up until recently, has taken passing in the council for granted," said Fidler. "I would say if everyone walked in today, for those of us that are committed, it's going to go down by a 2 to 1 margin."

Â