In Flatbush, Running with Baggage

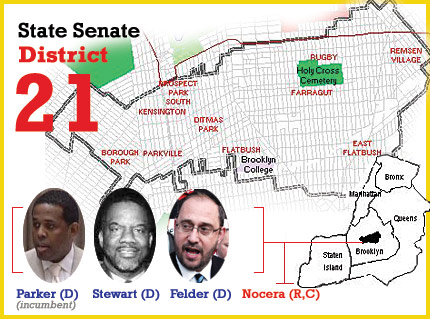

Update: After a three-way Democratic primary, Kevin Parker, the incumbent, clinched just over 10,000 votes to beat out council members Kendall Stewart, who had 2,651 votes, and Simcha Felder with 6,686 votes.

Now that is over, Parker, 41, faces a challenge from Republican Glenn Nocera. Nocera, 33, is a campus police officer at Brooklyn College and was born and raised in Brooklyn.

Parker, according to his latest campaign finance filings, has $15,803 left in his account. Nocera has $1,911.

Listening to the funk trio play at the Newkirk Avenue Block Party on a recent Saturday, Mannix Gordon fondly described Flatbush. "We're a very diverse area, and we're open to all views, all walks of life, and we're all about supporting people who have come from all over the world. We're about supporting diversity," said the Flatbush Development Corp.'s director of economic development as a group of giggling elementary-school girls -- two black, one white and one Hispanic -- scampered past him.

This fall, residents of Flatbush and the surrounding Brooklyn neighborhoods will choose from a diverse array of Democratic candidates to represent them in the State Senate. Each of the three contestants carries a distinct heritage -- and worrisome baggage.

Three-term incumbent Kevin Parker, an African American who serves as minority whip in the State Senate, once was considered a promising young star among Democrats in Albany. Then Parker's anger management issues became tabloid fodder when he punched a traffic agent who was ticketing his car in 2005. An old political rival and a former aide have also alleged that Parker assaulted them, although the senator denies these claims.

Kendall Stewart, the Caribbean-American City Council member who represents parts of Flatbush and East Flatbush in the 45th Council District, decided to challenge Parker last year, then watched as two of his own staffers became the poster children for the City Council's slush-fund scandal. Chief of Staff Asquith Reid and aide Joycinth Anderson face federal charges for allegedly taking $145,000 in city funds, some of which they purportedly used to pay for Stewart's campaign expenses. Both have pleaded not guilty. Stewart denies any knowledge of the deeds, but the initial momentum that, according to the Daily News, had earned him support from Brooklyn's Democratic establishment seems to have faded.

Then there is Simcha Felder, an Orthodox Jewish City Council member representing Borough Park and Kensington, who surprised almost everyone when he opted to enter the race for Parker's seat rather than run for city comptroller in 2009. An array of donors who had assumed Felder would run for the high city post helped him collect approximately $1.5 million in campaign funds before he announced his Senate candidacy . (Stewart's and Parker's campaigns in January reported balances of $52,817.25 and $14,097.83, respectively.) While Felder has a huge edge in funds, questions persist over whether a relatively conservative white Democrat can win in a district with so many black and Hispanic voters.

Felder and Stewart are among the many City Council members who will be forced out of office by term limits in 2009 and are seeking seeking other political jobs.

A Race on Race

The candidates agree on some issues but they differ over which of them would best serve the district and what a state senator should focus on. Many observers believe ethnicity could turn out being key.

The black majority -- 57 percent of residents, according to the latest available statistics -- is split between African Americans, who Parker says largely support him, and Caribbean Americans, who, based on interviews, appear to continue to back Stewart. Most of the white residents, approximately 22 percent of the district's population, are Jewish. A Hispanic minority of roughly 11 percent and a smaller Pakistani population help to round out the rest.

"At the local level, it takes too long" to learn about the candidates' positions on the issues, Flatbush resident Adrian Roberts said. "Whoever votes probably doesn't know anything about the candidates." What most people vote on, Roberts thinks, is race. "That's the first thing people pay attention to," said Roberts, an African American who has not been following the State Senate campaign.

Millisent Myers, a Jamaican American, says that Stewart will have a fighting chance thanks to the 21st district's Caribbean population. "I'm from Jamaica -- we vote. Black Americans don't vote" as consistently as Caribbean Americans, she said.

Drawing a significant number of votes from a different demographic could be difficult, according to Matt Ides, a Flatbush resident who serves as community liaison and legislative assistant to Manhattan State Senator Liz Krueger. Ides doubts Felder's ability to "reach out" to blacks from Flatbush. "When I saw he was running, I was like, no. He'll sweep his part of the district and that's it," Ides said as he relaxed at the Newkirk Avenue Block Party.

Felder disagrees. "It doesn't matter what [an] elected official looks like or who he prays to. The issue is accountability to the people he represents," he said.

Stewart and Parker could split the black vote, helping Felder. Parker says he's already seen this movie, though, and likes how it ends. "I have run this race before, in 2004, with a Caribbean candidate and a Jewish candidate. In three straight elections people have chosen my leadership," Parker said. He defeated Caribbean-American Wellington Sharpe and Noach Dear, an Orthodox Jew, in 2004.

A District of Immigrants

Ask Flatbush residents to name the political issue that most concerns them, and there is no telling what you'll hear. Leon Garrido said he most wanted to see the government find "jobs for the kids -- the kids need something to do." Gordon, the Flatbush Development Corp. staffer, pointed to "assistance for small businesses."

But the issue of immigration is near the top of many people's lists in a district that, according to Kevin Parker's Web site, includes the country's largest concentration of native Jamaicans, Trinidadians and Guyanese. Parker leads the Immigration Committee in the Senate, and Stewart chairs the Immigration Committee in the City Council.

Stewart, born on the island of St. Vincent, has sponsored successful bills on immigration, such as Intro 223, intended to prevent immigration consultants from exploiting customers, and Intro 38, which mandated that city agencies providing healthcare, food stamps and other services offer translations in six languages, including Spanish and Haitian Creole.

Stewart was not available for comment, but spokesperson Michael Roberts cited immigration as one of the candidate's strong points. In 2002, when Stewart took office, the city allocated $4 million for community groups and programs dealing with immigration, according to Roberts. "By the year 2003 he was getting $9 million," Roberts said.

Calling Stewart "a champion of immigrants' rights across the city," Roberts said Parker had not shown the same commitment to this issue. "What has he done in respect to immigration? What legislation has he passed on the state level?" Roberts said.

Indeed, Parker has yet to pass a bill he has written on any issue. But he blames this on being a Democrat in a State Senate controlled by Republicans. "That is a function of the fact that we are in the minority," Parker said, adding that he is "one of [Senate Republicans'] prime opponents." Parker last year introduced an immigration bill similar to Stewart's, requiring that the state issue licenses to consultants who provide assistance to immigrants, and has proposed legislation to grant immigrants who attend high school in New York the state-resident tuition rate at public colleges and universities.

Stewart has angered some Caribbean Americans. In 2003, it became known that an apartment building he owned has 144 violations, ranging from peeling lead paint to a lack of heat and hot water. Stewart blamed some of his tenants. "It's a cultural thing," Stewart said, according to the Daily News. "The Haitian folks, because of their poverty, will have five to eight people living in an apartment, and they will break the locks if one doesn't have a key."

Parker is ready to remind voters of the controversy. "Kendall has a problem because Kendall is a slumlord," Parker said. "People will look at his record, and part of his record is how he has behaved and the things he's said in this community."

Felder has not been a leader on immigration issues, but has sided with the City Council's Democratic majority on all votes relating to the issue. Felder said his own résumé extends beyond district-centric legislation. As a council member, he has chaired the Government Operation Committee. He is a primary sponsor of Intro 777, which would streamline the operations of the environmental control board; the bill recently passed the Governmental Operations Committee, but the Council has yet to vote on it. Felder was one of two primary sponsors of Intro 651-A, which tightens restriction on campaign donations from businesses that deal with the city. This bill, which Felder introduced at the mayor's request, became law last year.

State Senator, or Constituent Servant?

Parker paints himself as a reformer in Albany, noting "the things we've been able to change in the state government because of my presence. When I came, the state government had gone 21 years without a budget on time, and after one year we got a budget in on time."

He added, "We have made universal pre-K really universal for every child in the state. We've insured every child in the state. And this year we put more money into public education than ever was done before."

For their part, Felder and Stewart charge that Parker has neglected the more mundane concerns of his district. Parker has "a dismal record of delivering services to the community," said Felder, "and issues of transparency and accountability are certainly lacking." Felder said district residents needed a senator who is "going to pass laws that are going to help them in their everyday lives, not deal with the flooding in China."

Stewart takes a similar tack. A recent campaign flyer that earned online infamy promised Stewart would focus on "Bringing Home The Recourses" [sic] if elected -- language that, besides the misspelling, conjured uncomfortable memories of the slush-fund scandal.

Putting that aside, Roberts said Stewart played a key role in spurring construction of a mall at Nostrand and Flatbush avenues that created "250 jobs for young people."

Gordon thinks Parker could do more to help economic development in the district. "I would say [Parker's level of involvement] is okay ... not outstanding," Gordon said.

Parker, though, said he has served the district. "I'm not a city councilman so it is not my responsibility constitutionally to fill potholes," he said. "But my office does a lot of those things. My office is responsible to address the needs of the district and the city and the state.... You tell me what's more important than education for our children."

Mayor Mike and Questions of Conservatism

The Working Families Party, which frequently endorses Democratic candidates, has thrown its weight behind Parker. Spokesperson Dan Levitan said the senator has proved himself. The United Food and Commercial Workers, Local 1500 labor union agrees; it cites Parker's "strong history of support for working families." Stewart has not nabbed any major endorsements.

Meanwhile, Felder's moderate and conservative leanings on some issues, such as regulating businesses, have helped him win backing -- and money -- from Bloomberg. Felder voted against a bill -- one of a number on which he has been the only Democrat to vote no -- to force grocery stores and large outlets like Wal-Mart to contribute $2.50 an hour toward employees' health insurance. Bloomberg vetoed the legislation, but the Council overrode him. Felder also said that his religion prevents him from supporting gay marriage or voting for the openly lesbian City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, whom he supports.

Felder brushes aside the suggestion that such occasional conservative leanings could hinder him in the upcoming election. "As Ed Koch once said, pick 12 issues," Felder said in an e-mail. "If you agree with me on nine out of 12 issues, vote for me. If you agree with me on 12 out of 12 issues, see a psychiatrist. I believe with my record on quality of life legislation, campaign finance legislation and sanitation legislation, most of the district would agree with me on nine out of 12 issues."

Felder touts Bloomberg's backing as an asset. "I think that the mayor's support is invaluable. In fact, he won every [voting] district in this Senate district" in 2005, Felder said. "That's a testament to the fact that whether it's African Americans, Jamaicans, Italians, Jews, people see in the mayor a no-nonsense individual who's determined to do the right thing."

Felder hopes he can connect across racial lines as well. "When I got into office, somebody asked me, 'What is the most critical issue facing the city?' and I said race relations," Felder said. "And that's because [former Mayor Rudolph] Giuliani created an atmosphere where racial tensions were about to explode. The mayor, however, has done the opposite."

Pointing to Felder's opposition to abortion rights and support for parochial school vouchers, Parker calls Felder "out of step with this district.... Look at how much money he's gotten from the mayor on special projects," Parker said. "Simcha is a ... subsidiary of Bloomberg."

Parker has gone so far as to claim that Felder's candidacy is part of a Republican scheme, suggesting that, if elected, Felder would switch parties and sit with Senate Republicans. This is an especially volatile accusation in a year when New York Democrats hope to reestablish a senatorial majority. Felder flatly denies the charges.

Flatbush resident Pieranna Pieroni says she could care less about the conspiracy theories and ethnic politics. "Here's the question: are they talking to each other, or are they talking at each other?" said Pieroni, the coordinator of College Now Program at Brooklyn College. "We need somebody who can make everybody feel listened to and not somebody who's going to emphasize the differences among us. They should be starting that conversation."

For More Information

New York State Board of Elections

Relevant Articles:

Musical Chairs: Shuffling Seats in City Government

State Races and Incumbency -- How New York Is not Connecticut

Â

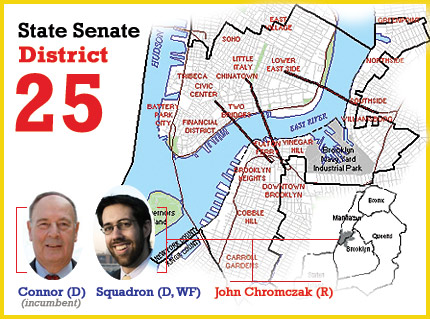

A Battle Over Reform in Manhattan and Brooklyn

Update: As originally written, this article incorrectly described Daniel Squadron's views on Brooklyn Bridge Park. Squadron has said he supports construction of a park but opposes any private housing development in it. The article below has been corrected.

In 2006, developer Ken Diamondstone came within 2,000 votes of defeating State Sen. Martin Connor in the Democratic primary, delivering one of the biggest scares of the 30-year incumbent's political career. The result seemed to signify that reform-minded voters held senior Democrats partly responsible for Albany's lamented political gridlock.

This year, Daniel Squadron, a 28-year-old political consultant and former aide to Sen. Charles Schumer, is trying to build on Diamondstone's near-success by unseating this elder of the New York Senate in a district that spans a swath of lower Manhattan and Brooklyn. In his effort to topple an incumbent -- always a long shot in New York -- Squadron has lined up support from his former boss, as well as some labor unions, and raised significant amounts of money.

Connor, though, has no plans to leave and talks about what he would do next year in Albany when, he hopes, Democrats will take control of the State Senate. "The overriding issue is that the Dems are going to win the State Senate," says Connor. "The kind of progressive changes I've been pushing for are finally going to get to the floor of the Senate."

Running Against Albany

Squadron's campaign needs to convince Democratic activists that the system in Albany is broken enough to justify the removal of a Connor, the former Senate minority leader. The challenger's quest has taken on the narrative of a young progressive taking on an older entrenched leader.

"I look at the way business is done in Albany and the effect it has on our neighborhoods, and it is broken," said Squadron. His plan for fixing the system involves striving for "increased accountability." He has offered such specifics as changing arcane Senate rules that prevent bills from getting out of committee. Squadron supports term limits because he feels the Senate has turned into an "ossified body" without them.

In Connor's view, Albany is "broken" only because a Republican Senate has blocked crucial Democratic legislative measures, and he dismisses implications he is part of the problem in the Capitol. He said he has sponsored measures on such issues as environmental regulation and tenants' rights, only to see them stalled in the Republican-controlled Senate. "It amuses me that people think anyone over 40 is not a progressive" he said. "I've been fighting those battles for years."

The Key Issues

Both candidates cite the need for affordable housing and legalizing same-sex marriage as top priorities.

The 25th District includes parts of the Lower East Side, Alphabet City, the Financial District, Tribeca, Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn. It is home to two of the largest and most controversial development projects in the city: the World Trade Center site and Atlantic Yards. These and other developments, along with gentrification in the district's Brooklyn neighborhoods, have spurred concern about the diminishing supply of reasonably priced housing.

Under state housing law, if a landlord spends over $2,000 upgrading an empty apartment it can be considered a "luxury" unit and so become exempt from rent regulation. Squadron and Connor believe this rule plays a key role in the housing crunch.

"If we don't repeal [luxury decontrol]," Squadron said, "we are going to wake up in a city that doesn't have living, breathing neighborhoods."

Connor is currently co-sponsoring a bill that would repeal the decontrol loophole. It faces little chance of success in the Republican-controlled Senate, but housing advocates hope their prospects will improve if Democrats take the Senate.

Looking at the Records

Other development issues, along with transportation, also have figured in the campaign. Squadron was the communications director in the successful effort to win voter approval for a bond issue to fund transportation improvements, including the Second Avenue Subway. He sees a need for longer-term changes to transportation infrastructure and supports the development of bus rapid transit lines in Manhattan. "All you need are cameras on the front of buses [to catch people who enter bus lanes] and more sequestered bus lanes," he said.

The two men endorse congestion pricing. Squadron has faulted Connor for not being enthusiastic enough about charging drivers to enter parts of Manhattan during peak hours. Connor said he endorses the concept, but was not enthusiastic about the mayor's proposed plan, which, he said, would have included exemptions on corporate limousines driving within the congestion pricing zone.

Squadron agrees that the original plan was flawed, but says that the mayor's push for congestion pricing represented a "historic opportunity." Both believe that it should be a priority if the Democrats retake the Senate.

Garnering Support

Many downtown and Brooklyn Democrats believe that the Democratic conference in the Senate has not stuck to its commitments. Squadron, though, also must convince power brokers and ordinary voters that his politics signal a real departure from Albany's status quo and that he can deliver on his reform agenda.

He has hailed some successes on the campaign trail. The Working Families Party views Squadron as part of a potential wave of young, reform-minded State Senate candidates, according to party spokesperson Dan Levitan. The Communication Workers of America, Hotel and Motel Trades Council and the Metropolitan Area Joint Board, Local 23-25, a garment workers union, have also backed him, while some large unions have yet to weigh in.

The influential Downtown Independent Democrats -- a reform-minded club with a membership of several hundred-endorsed Squadron on May 29. "Squadron came to us very early," club president Sean Sweeney said. "He had the free time to call people, ring doorbells, meet people, and come to club meetings." According to Sweeney, Squadron, who has been campaigning full-time since February, knocked on almost every door in the massive Independence Plaza apartment complex, at a time when Connor said his legislative obligations kept him off the campaign trail.

Every Democratic club in the district, though, has endorsed Connor, including the Lambda Independent Democrats of Brooklyn, of which Diamondstone is a member.

Progressive or Not?

Neither candidate reached the 60 percent threshold needed for an endorsement from the progressive advocacy group Democracy for New York City. Club financial director Louis Cohen cited Connor's handling of congestion pricing as one reason. "Some thought Connor hadn't been outspoken enough on congestion pricing," he said. Cohen added that the group would "rather not endorse if there isn't someone who's an 8 or a 9 on the progressive end of the agenda."

Progressives have criticized Connor on other issues as well. They cite his 1999 vote to kill the city's commuter tax. Connor said that the tax was going to expire within four months of the vote anyway and that suburban constituencies resented the tax, which had been in effect for almost 30 years.

Connor's support of the construction of condos and a hotel in Brooklyn Bridge Park has also been an issue. Advocates of the project say the private property in the park would provide needed funds for recreational facilities and open space. But Squadron claims that it represents a veiled attempt to hand parkland over to developers and said he opposes any housing development in the park. He charges that Connor "has failed to muster the funds and focused political will to get a real park built."

Progressive allied with Democracy for America have qualms about Squadron as well -- notably his ties to Schumer. Citing the senator's support for the Iraq war and the death penalty and his opposition to same-sex marriage, Cohen said, "Schumer wouldn't necessarily be voted progressive poster boy of the year." Squadron co-authored a book with Schumer and received his endorsement this past April.

For more information

Â

Let the Challenges Begin

By the stroke of midnight on July 10, candidates for office in New York City had to submit literally hundreds of carefully documented signatures to get a place on this year's September primary or November general election ballot. The filing at the Board of Election on lower Broadway ends one chapter of Campaign 2008 and starts another: the challenge phase, a part of campaigning in New York that one prominent election lawyer has likened to "a blood sport."

For the next week, election lawyers and campaign organizations will pour over rivals' petitions in the hopes of finding fatal flaws that could knock an opponent off the ballot. The Board of Elections will review challenges starting July 29 and going until Aug. 1 if necessary. If past experience can serve as a guide, some candidates will then take their cases to the courts, which will have to review them -- both charges and countercharges -- in advance of the Sept. 9 election.

It is all part of a system designed to benefit party organizations and incumbents and leave it so the "voter has little or no choice," said Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause New York. "There is a persistent pattern that results in no competition" in many districts.

Looking for Signatures

To get on the ballot, a Democrat in a typical city Assembly district must collect 500 signatures; a Democratic State Senate contender 1,000. People hoping to be the candidate of other parties generally need fewer names. A Republican in the overwhelmingly Democratic 58th Assembly District (Brownsville) would have to garner only 112 signatures, and a candidate hoping to land on the ballot as the Conservative Party's pick there needs merely seven names.

The people signing must live in the district and be members of the party in question. They can only sign one petition for each office.

Then there are rules about the format of petitions. If the petition has more than 10 pages, for example, it must also include a cover sheet with information about the candidate, the office and a statement that the petition includes the required number of signatures.

To make the game more interesting, the state also demands the players beat the clock. This year, candidates could not begin circulating petitions until June 3 and had to hand them in by July 10.

New York's laws are particularly strict. In 2001, the state attorney general's office observed, "No other state imposes such hurdles on ballot access."

Unlike many states, New York does not allow candidates to pay a filing fee in lieu of getting the signatures. And it requires more names: California has demanded only 65 signatures of gubernatorial candidates, about half the number a Republican candidate would need to run for State Assembly from a part of Harlem.

Navigating the Process

Facing this process, some candidates give up before they even get started. Candidates who want to try to beat the odds pay people to go out and try to collect an excess of signatures and then hire lawyers to defend them, adding to the expense of campaigns.

Daniel Squadron, who hopes to defeat incumbent State Sen. Martin Connor in the Democratic primary has announced that his campaign collected 8,000 signatures, or more than eight times the needed number. In a release Squadron said he did this because Connor is "an election lawyer who has knocked countless candidates off the ballot and has pursued legal challenges against every serious opponent he has faced since 1980." (For the record, Connor denies he plans a challenge.)

Those who do manage to make it through then face the challenges. The political parties and their lawyers "lie in wait " to contest signatures and knock any challenges off the ballot, Lerner said.

In 2005, it was reported that six of the 11 candidates running for a City Council seat on Manhattan's Lower East Side faced challenges from the Coalition for a District Alternative, a political club that actively supported outgoing Councilmember Margarita Lopez and Rosie Mendez, her protégé who was seeking the seat (and won).

In 2006 Juan Pagan, a Democratic candidate for Assembly District 74, submitted 1,000 signatures -- twice the number required. He was challenged anyway, and the Board of Elections discarded hundreds of names on the grounds that some of his petitions spelled out his middle name, while others used only his initial. The courts eventually sided with Pagan, but he complained at the time that the challenge cost him time and resources. He lost.

Not all challenges revolve around signatures. Under state law, candidates for the State Senate or Assembly must live in the district they seek to represent for at least 12 months immediately prior to the election (interestingly no such requirement exists for members of Congress).

Connor, for example, alleged that his 2006 opponent, Ken Diamondstone, did not meet that requirement. The Board of Elections sided with Connor. Diamondstone prevailed in court but lost the primary.

In Queens in 2006, the Democratic Party organization's candidate for an open Assembly seat, Ellen Young, charged that rival Grace Meng did not meet the residency rules. Meng left the race, even though she said she did live in the district. "Although I believe I have the required proof, i.e., tax forms, driver's license, etc., I do not want my family, friends, neighbors and supporters to go through a lengthy trial. I also do not want my contributions to be used toward a legal battle," she said in a prepared statement.

This year, Meng has filed again to run against Young. No word, yet, on whether she will provoke another challenge.

Obstacles to Change

New York's ballot requirements have long had their critics. In 2001, then Attorney General Eliot Spitzer's office issued a report calling for cutting the number of signatures required by half, lengthening the amount of time it would take to collect them and letting citizens sign more than one petition per office. Such changes, the report theorized, could help provoke greater voter interest in elections by giving people more choices at the polls.

The system though, has resisted change. A proposal offered by Gov. George Pataki in 1996 to make it easier to get on the ballot faltered in the legislature.

"When you have as dysfunctional a system as we have [where] the whole process is controlled by the legislature and the legislature is controlled by the parties, how likely is it that we can change that," Lerner said. "The people who we are looking to make this change are the people" who benefit from the existing system.

Take Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

In 2004, he assailed the rules and the challenges. "You don't have to beat the other guy based on positions or your ability to serve, all you gotta do is beat him because you got a better lawyer who can get him thrown off the ballot," Bloomberg said. "It's time to end this 'gotcha' kind of technique, where lawyers comb petitions to find some technical violation.

A year later, Bloomberg's campaign workers combed through signatures filed by Thomas Ognibene, a Queens politician who was seeking to challenge the mayor in the Republican primary. They got Ognibene thrown off the ballot.

The mayor's staff denied any contradiction. "I don't think it's a game of 'gotcha' to make sure the minimum number of signatures is valid," Bloomberg aide William Cunningham told the Times.

One person has managed to get a modicum of change to New York's election rules: Sen. John McCain. In 2000, this year's Republican candidate was challenging George W. Bush for the GOP nomination. A technical error threatened to keep the Arizona senator off New York's ballot, casting a temporary spotlight on New York's arcane election procedures. Eventually a judge ordered that McCain's name appear -- and Bush won the primary anyway.

The furor prompted adjustments in rules that make it far easier for Republican presidential aspirants to qualify for the state's primary. The rules for lowlier office, though, remain unchanged.

Â