Campaign Finance Board Considers Rules Changes, Including Controversial 'Coordination' Proposal

City Hall (photo via @NYCtransition)

Ahead of next year’s elections, the New York City Campaign Finance Board is considering a number of rules changes that would make the city campaign finance system more efficient and clear, and less onerous. One proposal on the list, however, has raised the hackles of unions, nonprofits, and campaign finance experts.

After every four-year city election cycle, the Campaign Finance Board is busy at work analyzing potential deficiencies in the campaign finance system and taking steps to plug any holes. Part of this is a routine update of campaign finance rules concerning a number of areas including, but not limited to, candidate registration and certification requirements, campaign recordkeeping, disclosure rules, contributions, and expenditures. The CFB tightens the nuts and bolts of the system, issuing clarifications for existing rules and scrapping those that have been rendered obsolete.

Ahead of the 2017 elections, the CFB is undertaking another round of rules updates. The board held a public hearing on Thursday to solicit feedback on a fairly long list of changes, some extremely technical, which were proposed last month.

Some proposals aim at reducing coordination between campaigns and independent expenditure groups (Super PACs), others make it easier for candidates to run campaigns and simplify documentations requirements while also tightening restrictions on how public matching funds may be used. These proposals also have the additional benefit of making the CFB’s post-election audit and enforcement procedures more effective.

Some of the more significant changes on the table deal with independent expenditures, which are anathema to the CFB’s mission of minimizing the effect of money on elections. In that vein, the CFB put forward three proposals, the first of which is perhaps the most important one in the entire package.

It would add two new factors to determine whether a campaign is coordinating with independent expenditure entities. The board would monitor whether a candidate raised funds for an independent spender or if the candidate and the entity had the same employees. If any of these factors, along with six others that the board already considers, are met in an election cycle, “the Board will assume an expenditure was coordinated unless there is evidence to the contrary,” reads a post on the CFB website.

Two other rule proposals would require increased disclosure from independent spenders, including providing information about who owns or contributes to a group’s contributors and making that information available on public communications.

Renowned campaign finance attorney Laurence Laufer, who served as general counsel to the CFB and helped formulate many of its policies, testified on Thursday and disagreed with a number of the CFB’s proposals. Chiefly, though, he expressed opposition to the one that would lead to a “rebuttable presumption against independence” of an expenditure and a campaign.

Laufer has also worked for the Campaign for One New York, a nonprofit set up by Mayor Bill de Blasio’s allies to promote his agenda. The Campaign for One New York and the de Blasio administration are being investigated by federal authorities over whether donors to the former got favorable treatment from the latter. The CFB also recently ruled that spending by the Campaign for One New York would not count toward de Blasio’s re-election campaign spending, though the board is aiming the new rule and seeking other changes to alter how elected officials and political nonprofits operate.

Speaking at the hearing, Laufer said the presumption that an expenditure is coordinated based on multiple factors is contrary to the existing law. He stressed that the burden of proof was on the CFB to show coordination rather than on a campaign to refute it. “In addition,” he argued, “this proposed presumption against independence is in derogation of First Amendment rights and it will chill the making of independent expenditures. That’s subject to strict scrutiny under First Amendment review because it’s treated essentially as a spending limit.”

Laufer also questioned the basis for the proposal, stating that it contradicts one of the CFB’s own past advisory opinions. Laufer submitted about a dozen pages of written testimony to the board as well, pointing out issues with other proposals in the package.

Brent Garin, deputy general counsel for SEIU Local 32BJ, a labor union, said at the hearing, “We fear that these proposed changes, particularly the imposition of the presumption of coordinated expenses, will inhibit our members’ participation in the political process.” He said the CFB should withdraw its proposal and submit an amended one to allow for an extended period of public comment. “Approving the current proposal would deprive the public of input for changes that drastically and negatively affect how community groups, advocacy organizations and unions can seek to effect social change,” he said.

Of the nine pieces of written testimony submitted to the CFB by those present at the hearing and other representatives of unions and nonprofit groups, seven questioned the rule change on presumption of coordination. Alexander Rabb, an attorney, on behalf of five nonprofit organizations, wrote that “issue advocacy activities will be burdened or effectively restrained,” by the rule. The New York City District Council of Carpenters and Joiners of America stated, “The new regulations create significant uncertainty regarding the use of independent expenditures and may even lack constitutionality.”

Among the other CFB proposals were ones that simplify and clarify rules that candidates in the past have found either onerous or vague. The CFB aims to clarify the rules for hiring volunteers, allowing campaigns to employ former volunteers as paid workers but prohibiting former paid workers to become volunteers. This would prevent campaigns from skirting spending limits.

One rule would eliminate a requirement that campaigns maintain a unique merchant account for credit card contributions, which was outdated and burdensome for campaigns in the 2013 election. Another reduces filing requirements for small campaigns and aligns the definition of a small campaign with state election law.

The board also put forward changes to how public funds provided to candidates can be used. One rule would require campaign communications to explicitly state that they are “paid for by” or “authorized by” a candidate or campaign committee. The board also clarified that claims for matching funds must be reported contemporaneously with contributions or they would be ineligible, and proposed new restrictions on candidates refunding contributions if they participate in the public matching funds program.

One rule, albeit a seemingly insignificant one, would allow candidates to wear pins or buttons in photos and videos that they provide to the CFB for its voter guide. (The prohibition on the accessories was a point of conflict between the CFB and Joseph Concannon, a candidate for a Queens City Council seat last year. Even U.S. Senator Charles Schumer weighed in, saying of the rule, “This is pointy headed bureaucracy at its worst.")

The CFB will now review the feedback it received and will consider adopting the final rules, with any amendments, at its next public hearing, possibly in October. Adopted rules would then be published in the City Record and go into effect 30 days later.

***

by Samar Khurshid, senior reporter, Gotham Gazette

@samarkhurshid @GothamGazette

New York State Legislative Primary Results

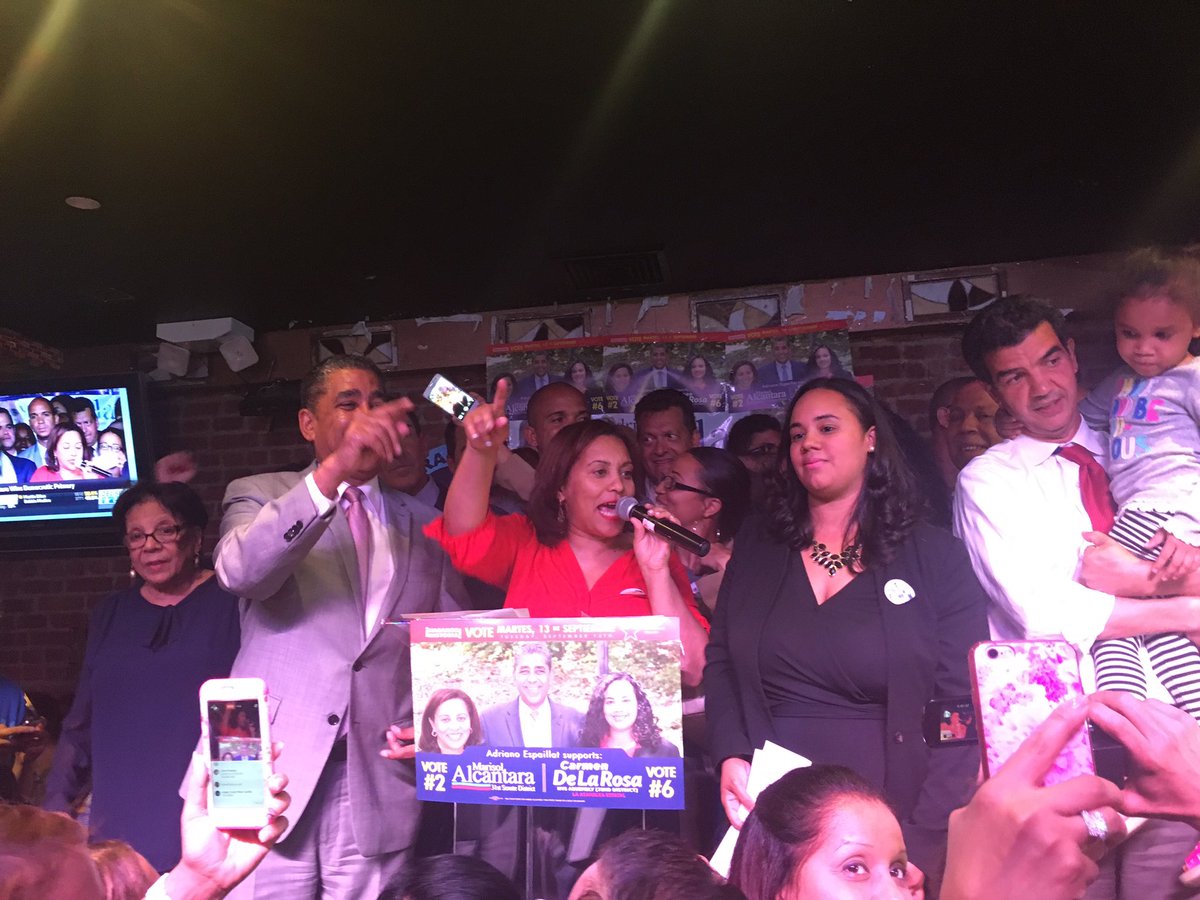

Marisol Alcantara and company celebrate (photo by Lis Smith on Twitter)

On New York’s third primary night of this election year, state legislative races in New York City were almost all Democratic and many incumbents did not face intra-party challenges.

In several state Senate and Assembly races across the city, Democratic primary winners were selected in fairly low voter turnout affairs and most will easily cruise to election in November - some won’t even have a Republican opponent.

Tuesday’s primaries saw multiple vacant seats being all-but-filled, while several seats being vacated by sitting legislators also saw the election of the next officeholder.

In what is a fairly rare occurrence, three New York City-based incumbents were defeated on Tuesday: Assemblymembers Alice Cancel in District 65, Sheldon Silver’s former district; Guillermo Linares in District 72; and Margaret Markey in District 30. They were defeated by Yuh-Line Niou; Carmen De La Rosa; and Brian Barnwell, respectively.

For open seats or seats being vacated, winners include Marisol Alcantara in Senate District 31; Jamaal Bailey in Senate District 36; Clyde Vanel in Assembly District 33; Robert Carroll in Assembly District 44; and Tremaine Wright in Assembly District 56.

Niou’s victory in the seat formerly held by Silver and briefly occupied by Cancel, who defeated Niou in a relatively close April special election, is a boost to the Working Families Party, who backed Niou, and a blow to Silver’s old downtown machine. It is a boost to the district’s large Chinese population and provides an opportunity for the district to in some ways step out of Silver’s long shadow. Niou will replace Cancel the already large Democratic Assembly majority. Cancel tweeted on Tuesday evening that she’ll “continue to work hard for my neighbors” and that she’ll be seen “again in two years,” seeming to allude to a rematch in 2018.

De La Rosa’s defeat of Linares and Alcantara’s win in the “open” seat currently held by Sen. Adriano Espaillat, who is heading to Congress, represent a consolidation of power for the three, City Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez, their allies, including Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, and other Uptown politicians and activists, especially those of Dominican descent, but also the larger Hispanic community.

Alcantara and Niou won in two crowded Democratic fields with a variety of political dynamics at play. Alcantara will join the Senate as Democrats hope to take control of the chamber and all of state government. Several key races in November will have significant impact on whether Democrats can seize that control from Republicans, who have had a governing coalition with the five-member Independent Democratic Conference, which Alcantara was supported by and is planning to join. Alcantara's win looks like the closest of the night in the city -- with 99% of precincts in the district reporting returns, she earned 8,309 votes (33.3%), compared to Micah Lasher's 7,737 (31.1%), Robert Jackson's 7,616 (30.6%), and Luis Tejada's 1,253 (5%). There are still absentee ballots to be counted, though. While Lasher initially held out conceding to analyze the potential impact of those ballots, he acknowledged by Wednesday evening that he did not see a path to victory.

Other winners on state legislative primary night include incumbents facing challenges. One was Sen. Gustavo Rivera, who again fended off a challenge from City Council Member Fernando Cabrera, who also ran in 2014.

The only New York City Republican in the state Legislature facing a primary was short-term incumbent Ron Castorina, who won his Staten Island primary by a wide margin. Democratic incumbents prevailing over their challengers included:

Senators James Sanders (SD10); Toby Ann Stavisky (AD16); Martin Dilan (SD18); Roxanne Persaud (SD19); Velmanette Montgomery (SD25); Ruben Diaz Sr. (SD32); and Rivera (SD33).

Assemblymembers Alicia Hyndman (AD29); Vivian Cooke (AD32); Rodneyse Bichotte (AD42); Pamela Harris (AD46); Latrice Walker (AD55); Deborah Glick (AD66); Linda Rosenthal (AD67); Daniel O’Donnell (AD69); Jose Rivera (AD78); Carmen Arroyo (AD84); Marcos Crespo (AD85); Victor Pichardo (AD86); and Luis Sepulveda (AD87).

For a full accounting of the votes and maps of the districts, both inside and outside of the city, see the WNYC election results page here.

***

by Ben Max, Gotham Gazette

@tweetBenMax @GothamGazette

Update: this article has been updated to reflect that Micah Lasher conceded in SD31.

Inside 311, the City’s ‘Front Door’ to Government

311 in 2013 (photo via the Mayor's Office on Flickr)

The vast LED board updated in real-time: 36,529 calls since midnight, it said for a late-afternoon moment one August day. Perched in a high-ceilinged room in Lower Manhattan, the board tallied work done and signified work to be done, with numbers jumping every few seconds as the New York City 311 call center buzzed with the steady hum of staff members speaking into headsets.

“Hello, and thank you for calling NYC 311.”

“Did you have a question about bus schedules today?”

“One moment.”

It was a relatively slow day for the nation’s largest municipal contact center, Call Center Director Joe Morrisroe explained. And, at about 4 p.m. it was not “peak hours,” which are generally around 11 a.m., Morrisroe said. At NYC 311, which serves as a “front door” to city government for New Yorkers, an average of 58,000 calls come in daily, comprised of anything from noise complaints to inquiries about city agencies to requests for new trees to be planted.

“In 2015 we handled over 20 million phone calls,” Morrisroe said. “If you take all the other municipal contact centers in the U.S., they didn’t total 20 million phone calls. And every major city has one.”

In addition to being a national outlier by volume, NYC 311 is currently fulfilling unprecedented functions even within the city. While Mayor Michael Bloomberg frequently referred to 311 as a resource for New Yorkers to suggest improvements for their city, Mayor Bill de Blasio has added to that purpose, indicating that callers can - and should - seek information about new initiatives like the city’s municipal identification program, IDNYC, minimum wage requirements, and more.

Since it was founded by the Bloomberg administration in 2003, 311’s operation has expanded steadily with the addition of 311 Online in 2009; text message and social media support in 2011; and a mobile app that launched in 2013. In 2015, 311 fielded 13 million online requests and over one million requests through its app, a figure Morrisroe says is growing rapidly.

The agency, funded through the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, was allocated over $41 million in the new Fiscal Year 2017 adopted budget, which took effect July 1. NYC 311 staffs approximately 400 employees annually, which has remained constant for the past few years, according to the 2016 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report.

“Historically, New York City wasn’t the first 311. When they first started in New York, they took cues from other cities,” said Morrisroe, who has been the call center director since 2008. “But right now we’re the benchmark, and as a matter of fact, other cities come to us.”

According to Morrisroe, 311 fits into de Blasio’s agenda of equity and financial mobility. In recent months, de Blasio has used press conferences to urge New Yorkers to call 311 for food stamps support, tenant concerns, and immigration services. De Blasio has repeatedly said New Yorkers should use 311 to find the nearest IDNYC center, reiterating this recommendation during an August 18 appearance on WNYC’s The Brian Lehrer Show. So far, 311 has already received over 500,000 total requests for information about IDNYC, a relatively new initiative, according to Morrisroe.

The three most common causes that lead New Yorkers to call 311 are noise complaints, complaints about inadequate heating in buildings, and requests for bus and subway information. But call center employees must be knowledgeable about each of the city’s agencies, and go through a 10-week training process at the start of employment.

“The customer doesn’t need to know how to ask their question or who to ask about,” Morrisroe said. “They just get to say, ‘Here’s what I need, can you help me?’”

When a customer first calls 311, they hear an automated message reminding them to hang up and dial 911 for emergencies. The automated message also lists whether alternate-side parking is in effect that day or the following day, which filters out a large share of callers, according to Morrisroe.

The average wait time to speak to a 311 responder is 14 seconds. In the call center, employees taking calls navigate two desktop computer monitors on which they record complaints, search for information on city agencies, and read results back to customers in real time. That afternoon, close to 100 employees monitored phones at the call center.

If callers have a complaint rather than a request for information, 311 operators will file it with the pertinent city agency and provide the customer with a tracking number. From there, the city agency is responsible for fixing the issue, and customers have the option of checking back with 311 on the progress of their complaint via phone, the 311 app, or the 311 website.

The agency also has a Twitter account, which responds to a constant flow of questions but does not file complaints. On one recent evening alone, the account directed a user to free city-funded sewing classes, listed steps to register a nonprofit, and fielded a complaint from a disgruntled library patron, who wrote, “just saw 3yr old boy pee n street cause rosedale library told him bathroom was broken then said it's 4staff only #smh.”

“Sorry to hear this. You can file a complaint about a NYC branch library/employee online,” 311 replied, along with a link to the appropriate complaint form.

This process is essentially non-stop. Complaints and requests flow into 311 24-hours-a-day, and the agency acts as a communication network between and among city agencies. Traffic is the heaviest on weekday mornings during the winter, when customers ask about travel conditions and government office closings, and on afternoons in the summer, when storm damage and heat concerns drive requests.

The number of employees in the call center reaches 400 during these peak hours and dwindles to about 20 late at night. The call center office also has a glassed-in manager’s office, which can act as a center of communications for the city during a crisis—two white phones are affixed to the wall; one a direct line to the city’s emergency management system, the other a direct line to the NYPD.

Although city crises are rare, Morrisroe said NYC 311 has played a crucial role during them. Throughout the duration of Hurricane Sandy, 311 employees slept in the call center on cots to provide overnight service. On the call center’s busiest day, during a 2011 blizzard, employees from other city agencies came in as backup to help field nearly 300,000 calls that came into the center in one 24-hour period.

“If there’s bad weather conditions and everything’s closed, that does not apply to 311 employees,” Morrisroe said. “We’re always here, we’re always open, and our employees are legendary for trudging through the snow if they need to in order to work.”

Despite this streamlined system, miscommunications still occur. While 311 is well-equipped to handle day-to-day complaints, there appears to be a lack of clarity for New Yorkers about when an issue should be directed to 311 or directly to another agency. It has also become clear that city agencies don’t take complaints or red flags and enter them into the 311 system.

Notably, City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito exemplified these issues in August when she tweeted a picture of a broken crosswalk sign to the NYC Department of Transportation and asked them to “take care of it.” A few hours later, the DOT account responded that crews had been notified, and added, “For fastest response, pedestrian or traffic signal issues should always be reported immediately by calling 311.”

Mark-Viverito responded with a tweet of incredulity, starting with “I'm sorry...whaaaat???” and told Gotham Gazette in a recent interview that the incident has made her consider a Council oversight hearing on how the city takes complaints. It is indeed a common refrain from city agencies on social media: call 311 with your issue.

While most agencies outside of NYC 311 do not have a mechanism for filing complaints or connecting customers to 311 directly, Morrisroe said 311 has an Agency Relations department that works to exchange information about trends and public awareness with other city agencies. Other departments do not, however, directly transfer complaints to 311—instead, those with complaints are usually instructed to call 311 directly.

This is an imperfect model, according to Noel Hidalgo, the executive director of BetaNYC, a civic technology movement. Following the Twitter exchange between Mark-Viverito and DOT, Hidalgo expressed frustration that Council members, community boards, and other agencies—like DOT—must refer customers to 311 to file complaints, rather than being able to quickly file the complaints themselves.

“How can we have a 21st century government when #govtech uses 20th century workflow?” Hidalgo tweeted, adding, “Let us not pave a cow path. Let us use service design & open source tech to build better.”

Mark-Viverito, the City Council speaker, had a similar thought after her experience. “I think the other issue here was, and that’s where we’ll probably do a hearing, is: how are complaints being logged from different city agencies,” Mark-Viverito told Gotham Gazette. “People use social media very aggressively these days. Other cities have been able to really incorporate that as a way of logging complaints. It seems like we may have some deficiencies in that.”

Despite an occasional run-in and perhaps the need for a rethinking of the overall system, the city’s ability to provide information and address complaints has been met with consistently high approval from customers - something likely to be touted at a Council hearing, if there is one. A 2015 customer satisfaction survey conducted by CFI Group, Inc., a private consultant, found that 85 percent of callers were satisfied with NYC 311, according to the Mayor’s Management Report. Morrisroe lauds his staff as the reason for such high ratings.

“It’s the dedication of the women and men who work here are,” Morrisroe said. “They live in New York City and they know the person on the other end of the phone is their neighbor, their fellow New Yorker. And I think that does something, I think that allows them to give better quality service than if you’re in the for-profit world.”

***

by Aaron Holmes, Gotham Gazette

@GothamGazette