Op-Ed: A Tale of Two New Yorks

It is the best of times; it is the worst of times. New York has always been a city of both wealth and poverty, but never more so than now. It’s easy to spot the wealth – getting a clear view of the poverty is a bit more complicated.

A recent WealthInsight study sets the number of millionaires in Manhattan at 389,100, defining millionaire as someone with net assets over $1 million excluding their primary residence. America's second city for millionaires is Los Angeles, with a mere 126,000. More breathtaking, Manhattan boast 70 billionaires — more than any other city in the world (Moscow is second with 64; L.A. has just 19). Why not in a city led by the world's wealthiest mayor, reportedly worth $27 billion?

The Center for Economic Opportunity, a city project initiated by Mayor Michael Bloomberg, recently issued its "Poverty Measures Annual Report" for the city with statistics through 2011. It's an interesting read because the CEO uses a poverty measure different than the official federal poverty rate.

The official rate produces a national poverty level without regional adjustment. The CEO measure adjusts for variations in area housing costs and it's based on National Academy of Science criteria reflecting what families actually spend on necessities, but also includes the value of noncash benefits like SNAP payments (food stamps), free or reduced rate school meals, Home Energy Assistance, housing assistance and so on, as income.

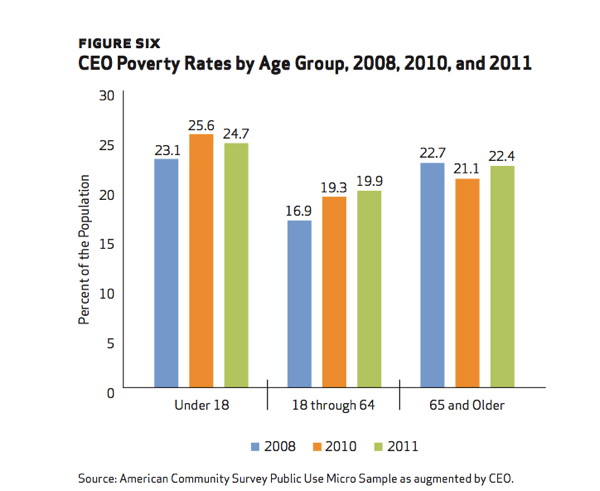

The official 2011 federal poverty rate in New York City was 19.3 percent , though it's now 21 percent . The 2011 CEO figure was 21.3 percent , a full 2 points higher. It was worse for hard-hit subcategories like non-citizens (28.9 percent ), kids under 18(24.7 percent ), single parent homes (30.9 percent ) and the Bronx (26 percent ). The poverty rate for kids in single parent homes was 34.7 percent . Asians CEO poverty rate was 26.5 percent and the rate for Hispanics was 25.3 percent .

Now in the throes of sequestration and a public policy of austerity, assistance resources for poor people have generally gone from few to really meager. There is Temporary Aid for Needy Families, but only for families with children and limited to an aggregate five years over a person's lifetime with the requirement that family adults work for the benefit. New York has a Safety Net Assistance program for those who have exhausted their lifetime federal benefits, but that generally has a two year limit for regular cash benefits.

New York City's safety net for homeless families in shelters used to include a priority for public housing or Section 8 vouchers, but that generally stopped after 2004, replaced by a transitional rent subsidy program which was also eliminated in April of 2012. Now the only generally available program for moving most homeless families to permanent housing is a job. That's if you can find one and if it pays a living wage.

New York's Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness estimates unemployment among homeless families at 57 percent. In fact, ICPH's 2011 survey of homeless parents found 68.5 percent unemployed.

Sequestration has foreclosed on some of New York City's tools. It visited Section 8 housing cuts on the three agencies issuing vouchers in New York City, meaning 5,000 planned housing vouchers won't be issued. New York City's Housing Preservation and Development Department lost $36 million and plans to cut 1,000 vouchers. "The real problem is," HPD Commissioner Matthew Wambua says, "these are our neediest tenants, the ones who cannot even afford the units in our developments."

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

He notes 32 percent of HPD's vouchers go to elderly renters and 44 percent to disabled people. Still, to avoid eliminating even more vouchers Wambua plans to reduce subsidies for many current Section 8 recipients, with reductions to subsidies as high as $400 a month.

New York City's Housing Authority and the state Department of Homes and Community Renewal both issue Section 8 vouchers in the city and have suffered sequestration cuts. They too won't issue a large number of planned vouchers.

The recently passed city budget does add some NYCHA resources, but not enough to overcome the public housing repair backlog, and certainly not resources to make up for sequestration cuts.

Even having a job isn't necessarily a get-out-of homelessness free card.

Most homeless people who find employment work in low wage jobs in fast food, child care and personal services, security work or retail sales. Fast food and security jobs often start near minimum wage. Even work in the healthcare-childcare and personal services fields pay an annual median income of $22,980 for homeless heads of household in New York City, according to the ICPH survey.

The federal poverty level for a family of four is $22,811, though the CEO sets New York City's poverty level at $30,945. Among the 22 percent of homeless families with a fulltime worker, most remain in poverty. Even among all New York families with two fulltime workers, 4.9 percent are in poverty.

A better way to understand poverty in New York City is to consider income inequality. Since 1967, the U.S. Census Bureau has used a measure, the Gini coefficient, sometimes referred to as the index of income correlation, as a measure of income inequality. It's a ratio of income dispersion comparing the median income of the highest quartile (20 percent ) to the lowest quartile median income. The higher the coefficient is, the greater the income inequality. If all families had the same income, the coefficient would be 0. If one family had all the income and the rest had none, it would be 1.0. In 1967, the first year the Census Bureau used it, the national Gini coefficient was .34. But in 1969, 1970 and again in 1974 it was as low as .326

The Census Bureau's 2011 national Gini coefficient was .477. But for Manhattan it was an extraordinary .601, the second highest number for any county in America. If Manhattan were a country, its Gini coefficient would be among the highest in the world — meaning the greatest income inequality — including most sub-Saharan nations, Middle Eastern emirates and third world countries. Manhattan's median income for the top 20 percent of earners was $391,022, compared to a $9,681 median for the lowest 20 percent. Top earners made better than 40 times what the bottom fifth did.

New York really is a tale of two cities: a rich gloriously city and a desperately poor one. The two cities cover the same geography but offer very different views. The ICPH study has a dire warning: "If changes are not made to the current system, family homelessness will only continue to grow" from its already historic highs.

All of the 21 percent living in poverty in America's richest city — nearly 1.75 million people — are at risk of homelessness if something isn't done about it.

Jeff Foreman is policy director at Care for the Homeless. Follow him on twitter @JeffForeman2.

Op-Ed: Stop-And-Frisk From A Mother's Perspective

I often wonder if I have what it takes to raise my black son in New York City.

While concerns about navigating public school application processes and scheduling play dates are common topics among parents, what often goes unspoken is something far more important: the unique challenges that come with parenting a young boy of color in New York City.

With nothing promised for young blacks and Latinos other than low expectations, street violence, negative peer influences and persistent police suspicion, how do we make sure that that our sons grow up safe and thriving? One step is putting an end to stop-and-frisk.

The New York City Police Department’s stop-and-frisk policy and all of its implications on crime and race are now at the forefront of political and social conversation.

With a decision pending in Floyd v. New York City, a high profile federal case challenging these practices, along with relentless community activism and a hotly contested mayoral campaign, now is the time to push for leadership that acknowledges the crisis in policing and proposes criminal justice policies and social reforms that will actually keep our young people safe without criminalizing them.

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

In a recent mayoral debate, Bill Thompson, the only candidate to address this issue from the perspective of parenting a black son, said “I’m the one who has to worry about my son getting shot on the streets of New York … And at the same point, I don't have to sacrifice his constitutional rights to make sure he is safe … I can have them both."

As a parent, I worry about my son’s safety. As a lawyer, I worry about his rights. Stop-and-frisk promotes neither.

In this climate of heated discussion, the mayoral candidates must acknowledge that stop-and-frisk has proven so damaging and polarizing a practice that it has become New York City’s civil rights issue of the day. Those vying for New York City’s top office must articulate proposals for credible alternatives to stop-and-frisk policing that go beyond weak promises to train police in cultural sensitivity and professionalism.

New York’s next mayor can learn from the successes of other cities that have developed anti-gang initiatives, gun control programs and community collaborations.

Ironically, proponents of stop-and-frisk often cite parental desire for increased youth safety as one of the most compelling reasons for continuing this policy. Like all mothers and fathers, parents of young men of color want their children safe from drugs, violence, and many of the other harmful influences of New York City’s streets.

Yet, draping stop-and-frisk in emotional appeals to safety overshadows its damaging reality. Moreover, those arguments overlook evidence showing that the decline in serious crime in New York City cannot be directly attributed to stop-and-frisk.

While violent crimes fell 29 percent in New York City from 2001 to 2010, other large cities that do not rely on an aggressive stop-and-frisk policy — such as Los Angeles, Baltimore and New Orleans — experienced larger declines in violent crime. In terms of illegal gun recovery, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union, from 2003 to 2012, the NYPD increased stops by 372,060, but recovered only 96 more guns, amounting to an additional recovery rate of 0.02 percent.

In fact, in 2011, the NYPD recovered illegal guns four times more often through methods not involving street stops.

Young black and Latino men are indisputably the targets of stop-and-frisk. Male youth of color between the ages of 14 and 24 comprise less than 5 percent of this city’s population, yet they accounted for 41 percent of stops in 2012.

Appallingly, more than 90 percent of black and Latino youth stopped by the police were innocent of any wrongdoing.

These unwarranted stops are not without consequence.

Most critiques of stop-and-frisk focus on damaged police-community relationships and the fraying of youths’ willingness to assist police investigations. While these are significant costs, parents should also consider the emerging evidence of the emotional and psychological harm caused by these often disrespectful, humiliating, and threatening interactions.

Nicholas Peart, a young black man named as one of the plaintiffs in the Floyd suit, gave a first person account of the toll of being stopped and frisked: “Essentially, I incorporated into my daily life the sense that I might find myself up against a wall or on the ground with an officer’s gun at my head. For a black man in his 20s like me, it’s just a fact of life in New York.”

There are many facts of life that I am prepared to teach my young son. This should not be one of them.

Nicole Smith Futrell is a clinical law professor in the Criminal Defense Clinic of Main Street Legal Services at the City University of New York School of Law.

Shining A Bright Light On Government Spending

Some say the West Coast has the best beaches, the Midwest has the friendliest people, and that you can't beat the cheesesteaks in Philly.

But financial transparency? Fugghedaboudit. New York City’s got everyone beaten by a mile.

That’s not just our opinion. That’s the view of the United States Public Interest Research Group, which in January named New York City the most transparent municipal government in the nation on the strength of Checkbook NYC, a website created by my office that allows users to view City spending.

Recently, however, we took steps to share the honor: we made the source code for CheckbookNYC.com freely available to every government that wants it.

This “open source” release means that cities and states across the country can leverage our investment in Checkbook NYC to create similar websites of their own.

We hope other places will like New York-style transparency, and we think they will.

On CheckbookNYC.com, you can find comprehensive, up-to-date information about the money that flows into or out of the City’s accounts. Details about spending, contracts, payroll, budget, revenue — it’s all there.

And the site is accessible to techies and luddites alike. Search functionality, graphic visualizations, and an intuitive interface make it easy for anyone to become a fiscal watchdog.

We built it for a simple reason: shining a bright light on government spending helps root out waste and ensure that tax dollars are spent wisely.

When governments know that their spending decisions can be easily scrutinized, they are more likely to use their resources prudently.

The site has the potential to save taxpayers big bucks. Imagine: If Checkbook NYC encourages the City’s decision-makers to rethink just one-tenth of one percent of our annual $70 billion budget, that’s a $70 million savings.

{sidebar id=14 align=right}

And that’s just for starters. The site can further drive costs down by encouraging competition among vendors and serving as an early warning system for projects that start to go over budget.

We aren’t giving the code away just out of the goodness of our hearts — we’re nice, but not that nice. We also want to mobilize the collective talents of local governments and technology engineers to improve upon what we’ve created so far.

It’s a civic experiment that we can all benefit from. Say Los Angeles starts using Checkbook, and then develops a new way to map where tax dollars are spent; every government that uses the platform will be able to benefit from Los Angeles’ innovation.

Following this theory, the more rapidly and widely Checkbook is adopted by other states and cities, the better it will become.

To encourage widespread adoption, two of the leading providers of government accounting systems, Oracle and CGI, are building Checkbook “adapters.” Their clients — hundreds of governments across the country — will be able to feed their financial data into the Checkbook system with the flip of a switch. And the company we worked with to build the site, REI Systems, is lending their technical expertise to help get open-sourcing off the ground as well.

The code for Checkbook NYC is available on GitHub.com. Local governments and techies should take a look, and get involved.

No one’s ever going to stop debating about where to find the nicest places, friendliest people, or tastiest grub. But when it comes to financial transparency, we can work together and all become the best.

John C. Liu is the New York City Comptroller.