Back-Stage Blood-Sport: Robert Carroll's The Believers

The campaign manager (both photos: Michael Abrams)

The hoary axiom that "politics ain't beanbag" is most often used these days when a candidate hits an opponent's character hard. But beanbag refers not just to a soft object that won't hurt; it's also a game with agreed-upon rules. And whether to play by, bend, or break the rules makes for good drama, whether on the campaign trail or stage. Working in the tradition of Gore Vidal's 1960 classic The Best Man, playwright Robert Carroll applies these questions to the rough-and-tumble world of New York City politics.

Set in Bill de Blasio's former city council district in and around Park Slope, Carroll's The Believers explores the world where most decisions get made: campaign headquarters. It's here where lead staffers hash out battle plans, often without the candidate's direct input. Carroll's play uniquely captures the adrenaline-rush felt inside campaign HQ as the day of reckoning approaches. And the Storm Theatre serves up a strong, fast-paced production, one that anyone interested in politics will likely appreciate.

Carroll, nearing 28, has grown up in city politics (and is currently the president of Central Brooklyn Independent Democrats). I asked to him to explain some background of the piece.

Your play is addressing a key ethical dilemma that arises in campaigns regarding 'how low will one side go?' in order to win. But most campaign decisions are really based on cold practical calculations. So are the "believers" here the starry-eyed idealists?

Practicality and idealism are often times thought of at opposite ends of the intellectual spectrum, but I think the play actually shows how idealism can lead to extremism and how those convictions can make people do terrible things under the guise of practicality. The main character betrays his idealism at the beginning of the play because he is so sure of the righteousness of his own beliefs. The conflict of the play revolves around whether the campaign will engage in defaming its leading opponent with a salacious piece of campaign literature on the morning of Election Day in hopes of suppressing Hasidic turnout in Borough Park. The main character—Chris, the campaign manager—justifies to himself that his decision to do the underhanded is morally valid because he believes the other side is so bad that no matter what he does the other side would be worse if they were to win. Of course, that underhanded and possibly practical choice made by Chris causes his downfall.

Your bio in the program says that you've worked on "countless campaigns" but the other night I sat next to Josh Skaller (currently a district leader in Brooklyn). He said that the storyline is an amalgam of a few specific races. Can you explain which ones?

I would say the play is part amalgamation of multiple campaigns, some of which I rely on more than others for reference points. However, many parts of the play are completely made up. I use my own experience to give authenticity, as well as build on, the larger metaphor about what people are willing to do for their beliefs. A political campaign is part marketing and part debate. Josh Skaller's 2009 city council campaign (against Brad Lander) was used as a foundation for the composites of some the characters and action in the play. I used some of the individuals who worked on that campaign because I personally respect them intellectually and fortuitously their sensibilities and conflict happen to be somewhat divergent from one another, which helps create dramatic conflict.

One of the characters was drawn from a 2010 congressional campaign I consulted on. And I also learned from my father, Jack Carroll, and his campaign work as both a candidate and an election lawyer. The play takes place in a very specific time, which I would rather not divulge since it is not readily apparent and is key to the conflict of the play. But I think it is important to note that I have had many politically astute people come see the show and many have thought certain references were in reference to different people or campaigns. I think this shows the universality of the themes and actions.

In the play, Chris (played convincingly by Taylor Anthony Miller) wrestles with the fact that his dad is a highly principled person. Are there any lessons he conveyed to you about the importance of staying clean in a dirty game?

I think the central question of the play and the central reason I am interested in politics is answering the question of "how" decisions are made, or the "process." I think if you are going to be involved in politics you should ask yourself 'how do we get where we want to go?' and 'how do we have a more fair system?' The play asks whether process/how we get somewhere is more important than holding the same beliefs as someone. So yes, my father instilled in me and my brothers a sense of fair play and honesty, and that process is very important. And that's what Chris is wrestling with.

As de Blasio's campaign illustrated, so much of politics is about stagecraft--e.g. the LICH arrest, Dante's hair, etc. But your play is about what goes on backstage. What made you decide to give the actual candidate such a minor role?

I wanted to allow the audience to imagine what the candidate was like, in order to create in their mind why these characters would do so much for this mysterious person. Furthermore, I didn't want the themes of the play to become muddled by making it about the personality of the candidates. You mentioned the de Blasio campaign's Dante ad as an example of political stagecraft, and while I agree, that ad also focused on Dante, not the candidate. I think lots of campaign theatrics do not revolve around the candidate but the message or themes they convey. I think often times people project their own feelings or hopes onto a candidate in the belief that it will fulfill something they desire.

***

The Storm Theatre's production of Robert Carroll's The Believers (directed by Stephen Logan Day) runs through November 1 at the Theatre of the Church of Notre Dame in Morningside Heights.

***

Theodore Hamm is chair of journalism and new media studies at St. Joseph's College in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn.

@HammerDaily

De Blasio's New Progressive Criminal Justice Initiatives Overshadowed by Prospect of More Police

New school safety agents (photo: @CommissBratton)

In the last week the de Blasio administration has announced three new initiatives designed to reduce some of the negative consequences of over-relying on criminal justice solutions to solve community problems. If his administration is serious about moving in this new direction, they need to come out against hiring additional police in next year's budget.

Last week it was announced that New York was planning to adopt aspects of Seattle's Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program, designed to divert low level offenders from the criminal justice system and into treatment and training programs. Seattle's program relies on officers to refer those they come into frequent contact with in relationship to drugs and prostitution. These are typically repeat offenders who regularly cycle in and out of jails, emergency rooms, and courts at great expense to the city and with only limited and temporary public benefit. Unfortunately, the new plan as conceptualized here is limited to non-arrestable violation offenses, undermining a key source of savings and possibly subjecting people to additional criminal justice involvement over minor offenses.

Hopefully this is just the warm up to a more comprehensive effort to deal directly with the myriad of social problems facing this difficult population.

Next, the mayor announced that he was ordering a major overhaul of school disciplinary procedures. This is great news for anyone who has been following the failed national trend of criminalizing young people through a growing number of zero tolerance policies. Since the NYPD took over school security, the number of young people arrested, cited, and suspended has increased dramatically. While this policy change does not directly affect NYPD school safety officers, it sends a message to school officials that they need to take greater responsibility for managing school safety without relying on ever more punitive measures. A recent report by a task force put together by former New York State top Judge, Judith Kaye, showed that well-trained principals in even the most difficult to manage schools have been able to dramatically reduce suspensions and arrests without undermining student safety.

Finally, the Department of Corrections announced a new policy this week that would end the use of solitary confinement for juveniles on Rikers Island. During a recent visit I made to Rikers I saw that almost 20% of juveniles were held in solitary conditions and in the process denied access to educational programs. A growing body of research has shown that solitary conditions are especially traumatic for juveniles and may serve to make them more violent and socially withdrawn upon release. This is a major positive development, leading some, like Council Member Elizabeth Crowley, to call for removing juveniles from Rikers altogether given its entrenched culture of violence.

All of this stands in stark contrast to last month's announcement by Police Commissioner Bill Bratton that in next year's budget cycle he intends to ask for at least 1,000 additional police officers. This would be a major step in the wrong direction and if included in the mayor's budget, would substantially undermine his claims of progressive criminal justice reform.

While the NYPD has an important part to play in creating social stability, its role has been dramatically over-extended in the last two decades. With the expansion of the War on Drugs and the adoption of Broken Windows-based policing, the NYPD has taken on a wide variety of tasks that it is not particularly well-suited for.

Despite decades of intensive anti-drug policing, which has given hundreds of thousands of mostly brown and black people criminal records, the NYPD has few victories to point to. While it's true that open air drug markets have been reduced through intensive criminalization, drugs are just as easily obtained as ever. Any high school student in New York can easily obtain any drug they choose. Overdose rates and other health problems associated with drug use have shown no signs of improvement either. It's time to take police out of the drug business and turn it over to public health officials. Decriminalization of drugs in parts of Europe has been a huge success leading to lower crime and better health outcomes. The full legalization of marijuana as in Colorado and Washington would be a start.

Despite the claims of its supporters, there is little to no academic evidence that Broken Windows policing has made us safer or is worth the high cost of criminalizing hundreds of thousands of mostly non-white New Yorkers every year. Yes, it can be used to drive out a homeless encampment or get rid of squeegee men, but it is not the reason for a multi-decade international crime drop that has occurred in hundreds of cities that never practiced it. It's time that we stopped criminalizing poverty and disorder and found more effective and less costly ways of improving the quality of life of all New Yorkers. Major investments in affordable housing, adequate mental health services, and meaningful employment opportunities are the humane, just, and cost effective ways of moving forward.

Some will dismiss this advice as a soft-hearted liberal appeal for more social spending. The evidence, however, is clear that we cannot police or incarcerate our way out of the social problems facing the city. And, even if we could, we can no longer afford the implications for racial and economic inequality that undergird such an approach. This administration understands this reality and needs to quit trying to have it both ways. It's time to double down on alternatives to criminalization.

***

Alex S. Vitale is associate professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and author of City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics. He is senior policy adviser to the Police Reform Organizing Project and serves on the New York State Advisory Committee to the US Civil Rights Commission. You can follow him on Twitter at @avitale.

Bill Bratton, Robert Peel, and Today's Police

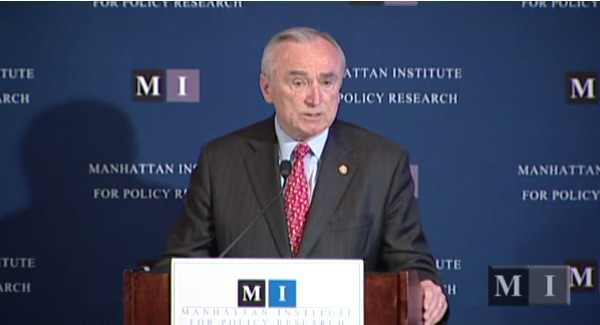

NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton speaking at a Manhattan Institute event

New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton often refers in public to his hero, Sir Robert Peel, a 19th century Englishman who espoused a community-oriented policing philosophy. The nine Peelian principles include such views as:

- The ability of the police to perform their duties is dependent upon public approval of police actions.

- Police must secure the willing cooperation of the public in voluntary observation of the law to be able to secure and maintain the respect of the public.

- Police seek and preserve public favor...by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to the law.

Peel's principles make no reference to a law enforcement approach resembling the "broken windows" theory promoted by Mr. Bratton, that a focus on low-level infractions like jaywalking, spitting on the sidewalk, or holding an open alcohol container will lead to a reduction in serious violent offenses. Nor does Mr. Peel mention the kind of numbers-driven policing that characterizes so much of the activity of NYPD officers.

I wonder what Mr. Peel and, in fact, Mr. Bratton would think about my recent conversation with a current New York City cop. While making a deposit at a bank near my office, I overheard the police officer posted there explaining to two tellers what the cops responsible for Eric Garner's death did wrong.

Interested in hearing more of his specific thoughts, I asked what he would have done differently. "First," he said, "you take your time and talk, your initial steps to persuade the guy to think better of sticking with his first impulse which is to object to the arrest. 'We can do this the easy way,' you say, 'or we can do it your way.' Then you explain that you have backup and that 'it won't be a fair fight, it's never a fair fight.'"

In addition, the officer explained, "you always take it very seriously when the person says something like 'I can't breathe', even if you think he's faking it. It's too dangerous not to."

I commented that it was especially troubling that the infraction involved, selling loose cigarettes, was so minor. "You know," the officer responded, "I'll be honest with you" -- a phrase that he repeated twice during our conversation -- "there are quotas. Each precinct has a conditions squad and they're under pressure to make their numbers. Arrests or tickets for quality of life things."

At this point in our back and forth, he was talking freely. Some of his other revealing thoughts and comments included:

-Quotas for evaluating police performance are 'unwritten', but each precinct has them and they are different for each neighborhood. So the numbers that the 'higher ups' expect you to meet are higher say, in Harlem, where he used to work than in Midtown Manhattan where the bank is located.

-"It is easier to arrest a black or brown kid" in Harlem. He stated that he would not under any circumstances arrest an Orthodox Jewish person from Brooklyn, where he also used to work. "They will make a cop's life miserable," he said, because they're well organized and can draw on their political connections.

-Once, due to an urgent family situation, he asked for an unplanned day off. "Like to help you out," his supervisor said, "but I have to check on your activity." 'Activity' is a code word for arrests, summonses, and stops; in other words, the officer would qualify for the day off only if he had met his quota.

-When I asked whether the quota system within the Department credited officers for positive activities like breaking up fights, settling disputes, or directing people in need of services like the homeless or mentally ill to places that offer appropriate services, he said no, only for sanctions like 'collars' or tickets.

-He said that sometimes you can see the trail for "quality of life" directives, pressure from headquarters to borough commanders, precinct captains to lieutenants, and sergeants to cops on the street.

-"I became a police officer because I wanted to help people," he said, "but the job doesn't support it." He shook his head. "I want to do the right thing but I'll get hanged for it."

I do not know exactly what "I'll get hanged for it" means here. I am fairly certain, though, that the officer referred to an on the ground culture within today's NYPD that is antagonistic to activities aimed at helping or befriending members of the community. I am also fairly certain that Mr. Peel and, for that matter, Mr. Bratton would not approve of such a police department. The key challenge for Mr. Bratton and for his boss, Mayor Bill de Blasio, and for all New Yorkers is how to create an NYPD that actually adheres to the "Peelian" principles and that fosters an institutional environment that rewards rather than intimidates officers who seek a constructive relationship with the people whom they are sworn to serve and protect.

***

Robert Gangi is the director of the Police Reform Organizing Project (PROP). Find PROP online at its website and on Facebook and Twitter.