An Emergency Correction to City Voter Disenfranchisement

Voting issues (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Jim Crow remains alive and all too well in Georgia, Florida, and, yes, New York City, where the most diverse field to seek the mayor’s office is preparing for June’s primary.

You know about news from Georgia, where Republicans -- citing false claims about fraud in the 2020 election -- have pushed through a law that, among other things, transfers some of the power to run Georgia elections from the secretary of state and local counties to a state board that conservatives will dominate. The law includes a ban on providing food and water to people waiting in line to vote.

You also likely know the challenges placed on Florida voters. In the run up to the 2020 elections, state Republicans stunted the state’s amendment granting voting rights to people with felony records. Republicans inserted a poll tax requirement that made those with felony records pay all fines and fees from their sentence before they could vote.

However, you likely don’t know the challenges New York City voters have. In New York, a decidedly liberal city, people in pre-trial detention are free to vote. However, as the June 22 primary nears, featuring hundreds of candidates representing the city’s diversity for dozens of local offices, the New York Department of Correction is not meeting its obligations to voting access. The majority of people have not received voter registration information, there are no posters or signs with voter information, and people have not received voter registration education. The failure to take these steps increases the barriers to voting among this population.

The New York City Charter requires DOC to implement a program to assist individuals with voting. Because eligible people in New York City jails are required to vote by absentee ballot, they must rely on DOC staff to exercise their rights. More importantly, a loophole further disenfranchises some in city jails. The last day to postmark an application for a ballot this year is June 15 and the last day to postmark a ballot is June 22. This means eligible voters admitted into custody after June 15 and held through June 22 won't be able to vote.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, Deputy Mayor Phillip Thompson, Board of Correction Executive Director Margaret Egan, new Department of Correction Commissioner Vincent Schiraldi, and the Board of Elections must listen to the Legal Aid Society and ensure voters in New York City jails have prompt and secure ballot access without hindrance. To accomplish this, they must do the following:

Provide a report on what steps have been taken to implement the voting policy in New York City jails announced last year at the September Board of Correction meeting.

Show that the BOC works with the DOC and the Board of Elections to get "emergency" poll sites set up in every jail, and allow every eligible incarcerated person to register and vote by affidavit during early voting (June 12-20) or on primary election day (June 22).

Prove the BOC requests from the DOC and the Board of Elections to report the number of eligible voters in DOC custody, the number of registration forms received, the number of registration forms they considered valid, the number of absentee ballot applications received and accepted as valid, and the number of absentee ballots received and accepted as valid.

There is a lot of confusion and misinformation surrounding access to voting. Ensuring appropriate accommodations for all voters — south and north of the Mason-Dixon Line, in jail or free — is the crucial first step in protecting a fundamental right to our democracy.

***

Ashish Prashar is the Global CMO at R/GA and a justice reform activist. He sits on the board of Exodus Transitional Community, Getting Out and Staying Out, Just Leadership, Leap Confronting Conflict and the Responsible Business Initiative for Justice. On Twitter @Ash_Prashar.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Moving Toward a Full Reopening of New York City Schools — The Time is Now

Kids back at school (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

On Tuesday, April 27, my kids returned to full-time in-person school for the first time since Friday the 13th of March, 2020. But approximately 600,000 kids in New York City are still learning from home. We must do better.

One surprising outcome of this pandemic: My three elementary school daughters -- Sadie, Juno and Ruby -- were thrilled at the promise of more time in the classroom. Their first morning back had the first-day-of-school energy as they giggled at reuniting friends they hadn't seen for a year and rushed in to see their enthusiastic and prepared teachers. In their words, they were "excited and scared at the same time." And the crowd of parents matched their emotions. As the kids literally skipped into schools, parents effusively thanked teachers and administrators. It felt normal...in the most joyful way possible.

We've been more fortunate than most during this period of at-home schooling -- mostly healthy, mostly employed, with flexibility in our professional schedules that have allowed us to create alternatives to Zoom School. But the chance to go back into a classroom -- where a trained professional can invest deeply in their education and where they can interact with their peers -- are academic and social-emotional opportunities we just can't give them at home.

This return was made possible by a few changes: The reduction of social-distancing guidelines from six feet to three feet for elementary schools; the discarding of the ‘two-case rule’ that had led to countless closures and disruptions across the city based on a dubious public health basis; and the additional opt-in period (something we’ve advocated for since the fall) means more of their classmates can rejoin them. Add in the increasing evidence that schools have not been a cause of significant community covid spread and the accelerating pace of vaccinations, and it feels like a safe opportunity to end the school year with nine or so weeks closer to normalcy.

But here's the real issue: What's good for my kids isn't actually solving the problem for most kids around the city. After the latest opt-in period families decided to return roughly 51,000 students back into school buildings. With a school system that serves more than 965,000 traditional public school students that means that 62% of New York City students will not enter a classroom this year, the vast majority of which are students of color. It's clear that the city must do more to hear and meet the concerns of their families if we're to have a successful, equitable full-time reopening in the fall.

So we must continue to raise the alarm: without a clear vision for the fall that's prioritized and resourced now -- something I and others have been calling on the city to provide for many months -- we won't actually have full-time, in-person school for many New York City students, and that will hurt all of us.

There are many reasons families aren't yet returning -- and I’ve been talking to parents and administrators across School District 15 as well as around the city about these reasons. Some are waiting until their families or communities are fully vaccinated. Some want to see how the covid variants play out. Many chose not to opt in to this final period because they have a house-of-cards schedule of childcare that could fall at any moment and it cannot be altered. And for some students remote school removes social anxiety and distractions and is better for their learning.

But it's also become clear that many parents just aren't willing to place a bet on the Department of Education. Years of underfunding have left schools in disrepair, classrooms crowded, and many kids behind. If your school didn't have soap in the bathrooms pre-pandemic, you may not believe the school would have the resources to ensure regular hand-washing. If your classroom was overcrowded to begin with or if you experienced high teacher turnover, you might not think your child's best interests will be served during these uncertain times by heading into uncertain classrooms.

I was frustrated that the city wasn’t collecting or sharing the concerns of remote families in a transparent way, making it impossible to address those concerns. So I decided to ask remote families directly, and working with City Council Member Brad Lander, we had a team of volunteers survey a geographically and racially representative set of parents and caregivers around the city about their plans for the fall. Some news was encouraging: A significant majority plan to return to in-person school in the fall. Other news less so: Most families said they hadn’t been asked about their fall plans yet. Many families brought up specific health questions the city needs to address, and 8-15% said they are unlikely to return to in-person school, which can give administrators and city leaders some guidance for their planning. And one other important note: Principals are the most trusted voices on returning to school for these remote-only families, more than teachers, and far more than the Schools Chancellor or Mayor.

To get more students back in the classroom, we need to ensure schools are truly open five days a week, limit unnecessary closures that create disruptions for families, make sure teachers and staff have had adequate access to vaccinations, and ensure vaccination requirements align with other requirements across our system. Parents need schools to resume early drop-off and afterschool programs -- both for the enrichment of the students and the consistency of schedule. Our high school students must be taught by in-person teachers instead of reporting to classrooms to learn via video. And all of this needs to be communicated proactively and repeatedly, ideally by principals and teachers, who also use this as an opportunity to listen to remote families, ask about their concerns, and help address them.

Furthermore, parents need to understand the alternative: There has been talk of a remote option being offered for the fall, though there are no details or plans. Will that be provided by each school -- overburdening principals to create dual programs for another year -- or run district-wide? Will it be a citywide one-size-fits-all remote curriculum, or a series of remote academies, conducted in different languages and focusing on different learning styles? Until families understand these details, many may not commit to coming back, leaving principals uncertain about enrollment numbers and unable to make clear staffing plans, ensuring a late summer of confusion and frustration for administrators, teachers, and families.

We are seeing an unprecedented infusion of funds into our schools and how that money is spent will speak to our priorities as a community. We could decrease class sizes, expand enrichment opportunities, ensure multilingual communications, add individual and small-group tutoring capacity, invest in community-wide digital literacy, and so much more. And we can try to hold onto some of what schools have experimented with this year: smaller cohorts, more outdoor time, individual learning, a move away from standardized tests. But until we hear that vision -- and help shape it -- many families might imagine a return to in-person school will be reverting to the models that weren't working pre-covid and continuing some that haven’t worked during covid.

Every day that there isn't a clear vision for the fall -- one that truly dives deep into listening to parents, beyond surveys, including through the many community-based non-profits outside the Department of Education that are serving our families and kids on a regular basis; one that draws a clear, consistent picture of what schools will look like, as best as we can know; one that gives us confidence that the "plan" won't change every few weeks, that it will keep our students and teachers safe and, just as critically, be engaging, enriching, and joyful -- is a barrier to a healthier, more equitable, more successful reopening. Our surveying is just a start to understanding these concerns and providing a roadmap for the city -- but we can build on this with more engagement citywide, including empowering principals to reach out to parents to hear their concerns, answer their questions, and give them confidence to come back in-person.

My kids have the privilege of attending a public school where the administration communicates with us through multiple channels and where the Parents Association can fund additional recess coaches to make outdoor time part of every day (including, now, lunchtime), and where, as English speakers with digital literacy, we're able to absorb the range of updates from our teachers, administrators, and city officials. And they’ve had the benefits both of our employer-based health care and of accessible covid testing locations, plus parents, grandparents, and aunts who have all had the opportunity to get fully vaccinated. All of that just isn't true for large numbers of our city's families.

As a result, my kids are back in a classroom, with professional teachers and many of their friends, while many are not. And if that continues in the fall, it'll exacerbate the inequities and segregation in our educational system even further. The promise of a safe and equitable full school reopening needs to work for all students and families, not just mine.

****

Justin Krebs is a parent of three elementary school students in Brooklyn, New York, a parent leader at his own school and in the community school district Presidents Council, and a candidate for City Council in District 39. These perspectives are his own and do not represent the Parents Association or Presidents Council. On Twitter @justinmkrebs.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

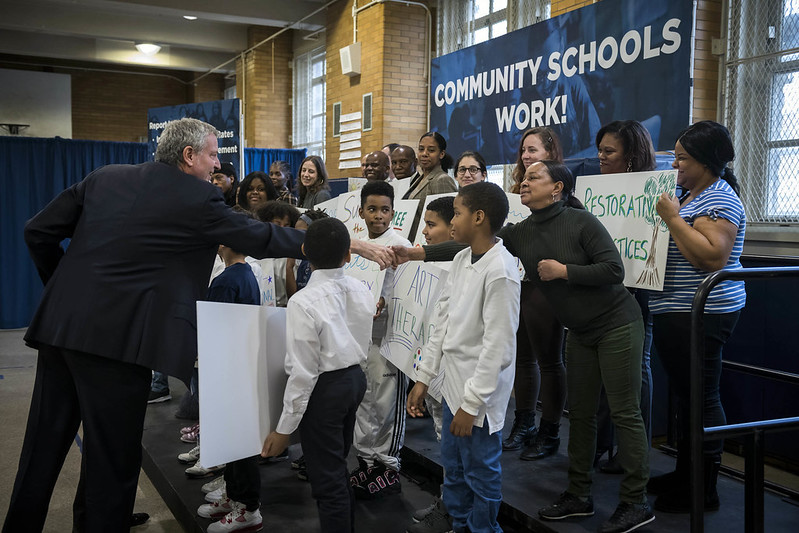

Community Schools are the Answer: An Open Letter to the New York City Mayoral Candidates

A community school celebration (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Dear Candidates for Mayor:

Among the myriad issues you are discussing during public forums and interviews, none is more important than the education of New York City’s children and adolescents. You have responded to, and raised, several aspects of our educational landscape in these venues but we have heard precious little about whether you support expansion of the city’s community schools initiative, an effort that began in response to a de Blasio campaign promise in 2013—a promise on which he and his administration more than delivered.

Especially now, as New York City recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, voters want to know what you propose as viable strategies to promote health, healing, and learning. In my view, the best answer is community schools.

Community schools organize school and community resources around student success. In 2013, candidate de Blasio said he would increase by 100 the number of community schools in New York City. By the end of his first term, the actual number had increased to more than 250. City Hall and the Department of Education worked together to leverage leadership and funding that allowed these schools—chosen according to the level of unmet need among their students and families—to marshal additional human and financial resources. In alignment with national best practice, each school conducted a thorough assets and needs assessment and then engaged community partners that brought the requisite skills, services, and supports into their schools on a consistent basis.

Even more important than the number of community schools are the results they have achieved. A multi-year impact study of the initiative conducted by the RAND Corporation reported a reduction in student chronic absence as an early outcome and, later, found an increase in academics and graduation rates for all students—particularly for students living in temporary housing and for Black and brown students.

These results were achieved through the mobilization of community resources and their integration into the core instructional work of these community schools—resources like vision screenings coupled with free eyeglasses provided by Warby Parker; mental health screenings and services offered by a combination of public and private clinicians; afterschool and summer enrichment programs that provided child care for working families and extra learning opportunities for students; and a cadre of specially trained social work interns, sponsored by New York City’s six schools of social work, who assist public school students living in temporary housing.

A lesser-known part of the New York City community school story is the role of the Coalition for Educational Justice, a parent advocacy organization that identified community schools as a preferred reform strategy after surveying and consulting with families across the city. As CEJ’s Natasha Capers has written, CEJ implemented a campaign in early 2013 to make improving public education a key issue in that upcoming mayoral race; this campaign included extensive family outreach and consultation over several months. Capers noted that, with the help of a design team of policy experts, CEJ then issued a roadmap for the next mayor that highlighted all the top ideas, including community schools. Parent demand as an instigator for this reform makes its continuation and expansion even more urgent because COVID-19 has demonstrated that the supports and services offered by community schools are needed by New York City’s families now more than ever.

Taken together, these factors—family demand, documented success, new post-COVID realities—make expansion of the community school strategy a no-brainer. Recent action by Mayor de Blasio and the City Council will ensure continuation and growth of community schools through 2022, but advocates are rightly concerned about the future that lies beyond the current administration. The city can use its experience over the past eight years in leveraging and making better use of existing resources while also tapping into new federal dollars, including those allocated for high-need schools in the American Rescue Plan Act.

In addition, the Biden administration has proposed expanding the Federal Full-Service Community Schools Program in the U. S. Department of Education from its current annual budget of $30 million to $442 million in 2022. New York City should be first in line to capitalize on this national momentum. But, to do so, we need a Mayor who believes in the idea of every school a community school.

***

Jane Quinn is currently a doctoral student in Urban Education at the City University of New York. From 2000 through 2018, she served as Director of the Children’s Aid National Center for Community Schools.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.