The Suburbs Need to Finally Step Up in New York Housing Crisis

Housing in view (photo: Governor's Office)

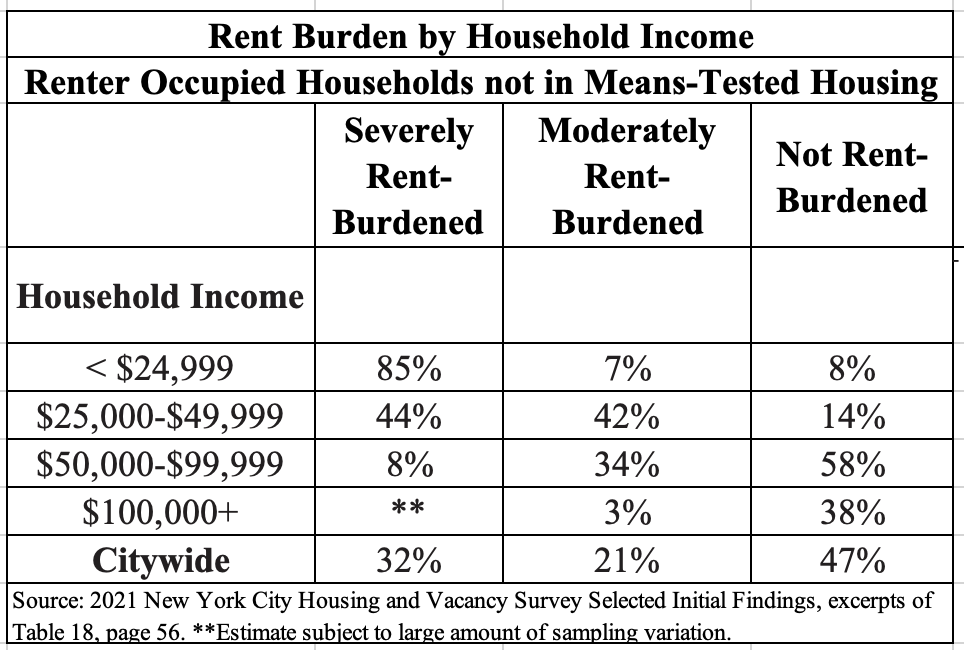

It is easy to focus on New York City proper when thinking about the affordable housing crisis. Initial findings from the city’s triennial Housing and Vacancy Survey, for example, show that 32% of all city renters not living in means-tested housing are severely rent-burdened, meaning paying more than 50% of household income for rent. It’s 85% for households with income of less than $25,000.

But, as New York City Mayor Eric Adams prepares to release his housing plan – building on an outline of proposed citywide zoning amendments he recently presented and other elements his appointees have offered – we cannot continue to ignore the regional dimension to that crisis.

More than 50 years ago, the Regional Plan Association issued a report on housing opportunities in the New York City region, noting in 1969 that there was “growing apartheid” and a “severe limitation” in the suburbs on housing available to members of minority groups. The report further referenced the fact that there was disproportionately little affordable housing in the suburbs and that the growing apartheid system “placed a severe and unfair burden on local governments [most notably New York City] which are left with inordinate costs resulting from poverty.”

Fast-forward to the present. According to 2020 Census data, there are still in Westchester at least 16 towns and villages that have Black populations of less than 3%. Along with the racial segregation, the disproportionate costs borne by New York City as compared with its neighbors in respect to providing both affordable housing and social services remains as well.

Using 2020 five-year American Community Survey data compiled by Social Explorer, I found that only 13.1% of the combined households in Westchester, Nassau, and Suffolk had household income of less than $30,000; by comparison, the percent of New York City households with household income of less than $30,000 was 26.1%.

In other words, the percentage of New York City households defined as “extremely low income” is double that of its suburban counterparts. (At the other end of the spectrum, the percentage of suburban households with household income greater than $150,000 was 34.7%, significantly higher than the 20.1% of New York City households that met that criterion.)

So for all the ideas about what to do about affordability within New York City – including some recent ones of my own – it is important not to forget the critical role that New York’s suburbs are supposed to be playing in providing a fair share of regional affordable housing need.

Despite their acting otherwise, New York City’s suburbs are not beyond the reach of state law (which has long required that each municipality plan for its share of regional housing need). They are not supposed to be beyond the reach of federal law, either. The Fair Housing Act makes exclusionary zoning – like those suburban zoning codes that preclude the building of multiple-family, mixed-income housing – illegal.

Yet these suburbs have, for decades, defied state and federal law and failed to build much housing. From 2010 to 2020, for example, the Regional Plan Association calculates that Nassau and Suffolk Counties had fewer than 10 building permits issued per 1,000 residents, and that Westchester clocked in at only 13.5. Manhattan housing starts per 1,000 residents – inadequate still – were a much higher 30.1.

One notable recent example of the active suburban resistance to building affordable housing is found in the fate of the landmark housing desegregation consent decree that the Anti-Discrimination Center won against Westchester in a case brought under the federal False Claims Act.

The consent decree entered in the case had, according to a brief filed by several fair housing organizations, “provided more opportunity to effect significant structural change in hyper-segregated residential housing patterns than any other legal proceeding in the last 25 years.” Ultimately, though, the decree had to be enforced by the federal government and its monitors, who were unprepared to do so. They snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by failing to have the political will to overcome the county’s resistance.

Even more recently, New York Governor Kathy Hochul proposed early this year what she described as “sweeping plans” to address the housing affordability crisis, including zoning changes to allow accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods and to override local limits on multi-family, transit-oriented development. These zoning initiatives quickly ran into intense suburban opposition, and were dropped from Hochul’s budget proposal.

New York’s Department of City Planning would appear to understand at least on some levels that the city’s housing needs exist within a regional context, but the city’s leadership has never done more than engage in a “pretty, please” approach to seeking regional equity (to be honest, it is not even clear whether city leadership has gone as far as “pretty, please”). The failure of New York City’s suburban neighbors to build their fair share of affordable housing not only hurts their own residents, that failure contributes significantly to New York City’s affordable housing crisis as well. And the failure of the city to press its neighbors to do more has been a grave error.

The city should open its eyes, exert real political will, and be prepared to use all the tools it has available – including state and federal legal tools that I am confident would be successful – to bring affordable-housing “fair share” to the metropolitan region.

***

Craig Gurian is executive director of the Anti-Discrimination Center, based in New York City. On Twitter @antibiaslaw.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Public Health, Public Safety, and the New York City Budget

Mayor Adams at an announcement (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

Typically, the scorching hot summer months bring a rise in violence, but there’s much more than temperature at play. Last fall, a Violence Interrupter in Brooklyn shared with us his greatest concerns as we moved to the colder months. He noted that the sunset of extended unemployment benefits would cause more families to be under stress, leading more kids to leave their turbulent home environment in search of solace and kinship in the streets.

It’s not complicated from his perspective.

But this simple and poignant analysis of how poverty leads to violence is rarely reflected in conversations around the city budget.

If we allow public safety to be defined in the context of policing, prosecution, and incarceration, we should not be surprised when we see our jails and courts overwhelmed. Court delays have skyrocketed since the covid pandemic and Rikers Island remains under federal monitoring. Just last month the monitor released another report detailing the mismanagement and violence faced by those detained at Rikers and by the correction officers themselves. We now spend more than half a million dollars annually per client in the Department of Correction – about five times more than in Chicago and Los Angeles – clearly more money for police and jails will not fix this problem.

No Health, No Justice

The Commission on Community Reinvestment and the Closure of Rikers Island released a report last December detailing the root causes of incarceration and the various city agencies empowered to pursue prevention and community-oriented public safety initiatives. From street lights to school nutrition, from youth employment to sanitation, the city’s investments in our residents and our communities pay dividends for decades to come.

Notably, the Mayor is obligated by local law to respond to the recommendations set forth in the report, with oversight from the City Council. The Commission’s Subcommittee on Health laid out a few core principles to frame this conversation. As with our violence interrupter’s story above, the first idea is a simple one: Ensure quality health care is available in the community so the carceral system becomes the last resort for accessing health-care services.

Who could argue with that? Why isn’t this already the case? Regrettably, our reality is far from this ideal.

The Commission report describes health-care deserts, akin to the food deserts we learned about over the past decade. The same communities that are overburdened by the criminal justice system also suffer from worse physical health, mental health, substance use, and social outcomes, mainly due to a lack of access to quality care. Despite the best efforts of the city health department to highlight these disparities, and marshal appropriate resources to respond, this generational inequity persists.

The next section of the report highlights key opportunities to pursue health equity through reforms to the State Medicaid system. The state’s current plan prioritizes individuals and families impacted by the criminal legal system. Most notably, it seeks to activate 30 days of Medicaid coverage prior to release from incarceration, to allow community-based providers to engage clients before they transition back to the community. This will improve the health and stability of some of our most vulnerable residents, and will save taxpayer dollars by preventing emergency room visits and unnecessary hospitalizations.

The state is also planning to roll out hundreds of millions of dollars in opioid settlement funds in the next decade, offering us the chance to build the community substance use treatment and mental health service infrastructure that was promised in the 1970s but never fully materialized. This would mean the ability to access care, same-day, in your own community. No two-month wait list, no travel across the city or county, no wrong door – just quality accessible services including peer supports, safe stabilization spaces, and affordable medications.

These changes will arrive too late for a client we’ll call Stephanie, whose plight is all too common. Stephanie suffers from serious mental illness and when she left prison in 2016 she went to the emergency room for a psychiatric evaluation. Her parole officer threatened to send her back to prison if she did not start taking the $2,000/month prescription medications listed in her release documents. But those documents also listed an incorrect address for Stephanie, preventing her insurance coverage from activating upon her release. With proper insurance coverage, Stephanie could have returned to the same out-patient psychiatric provider she used prior to her incarceration, but she was left without access to this care. The stress of these events further complicated Stephanie’s mental illness, and she was soon admitted to the inpatient psych unit following an incident of self-harm. All because someone listed the wrong address on her paperwork.

We can help future Stephanies and the city can lead the way.

The New York City Council recently held hearings to examine Mayor Adams’ latest budget proposal, hearing from his appointed agency leaders on how they plan to serve the residents of New York City in the year ahead. City budget negotiations are now ongoing before an adopted budget is due by the end of the month.

Let’s take the lead from our sage Violence Interrupter and keep it simple. Protect, support and build up the weakest and most vulnerable among us, and we can all thrive together. That’s the New York Stephanie and the rest of us deserve.

***

Tracie Gardner serves as the Senior Vice President of Policy Advocacy at Legal Action Center. Jeffrey Coots, JD, MPH, directs the From Punishment to Public Health (P2PH) initiative at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The Rise in Asian Hate is Taking a Mental Toll on New York’s Asian and Pacific Islander Community

Stop Asian Hate rally (photo: Gerardo Romo/City Council)

As doctors, we have seen the horrific impact of COVID-19, including the adverse effects of our society's socioeconomic divides, social injustices, and widespread racism during this same period. These social ills coupled with the profound health impact the pandemic has had on our nation have intensified the mental health crisis facing Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI). Xenophobia in the United States exploded in the early months of the pandemic and has shown us that what followed the onset of the pandemic was a plague of racial prejudice.

Racism, which results in mental and physical trauma, is a primary cause in the rise of mental health issues across AAPI communities.

In a recent national survey by AAPI Data and Momentive, anti-Asian hate crimes have increased during the pandemic: 1 in 6 Asian American adults reported experiencing a hate crime in 2021, up from 1 in 8 in 2020. Cities across the country are experiencing sprees of hate crimes targeting the AAPI population and other communities of color. According to preliminary analysis, reports of hate crimes skyrocketed in 2021 in more than a dozen of America's largest cities, with a record number of Asian Americans saying they were targets. In New York City, the NYPD reported a 361% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes. And in a recent national poll, 71% of Asian Americans said they felt discriminated against in the U.S. today.

This disturbing increase in hate is taking a significant toll on an already troubled mental and behavioral health care approach in demographics that identify as Asian American and Pacific Islander.

We know that approximately 77% of the AAPI population speaks a language other than English at home. From a medical perspective, telephonic interpreter services are available to patients; however, many Asian patients feel uncomfortable using these services when discussing sensitive issues regarding mental health. Discussing mental health may also be considered culturally taboo within this demographic, making it even more difficult to identify symptoms and treat depression or anxiety. Additionally, roughly two-thirds of U.S. psychologists say their waitlists have gotten longer since the pandemic started. The trouble of finding a therapist or psychiatrist who understands specific AAPI cultural backgrounds adds further barriers to care.

With the rise of Asian hate and the lasting physical and emotional scars of COVID-19, we as medical professionals are charged to help care for the AAPI community in its greatest time of need.

Beyond legal and policy changes, we have the intel, tools, access, and obligation to act now to best serve our patients and communities where they are. Listening to and understanding the community's needs are at the core of what is required to deal with trauma. Physicians need more educational training that highlights overlooked medical issues in the AAPI community, including mental health, early hepatitis screenings, addictions, food insecurities, and foods unique to specific ethnic groups and their relationship to chronic diseases.

For instance, at AdvantageCare Physicians (ACPNY), we are tackling the psychosocial aspects of delivering healthcare services to the AAPI community head-on with cultural competency courses for our healthcare providers. We also formed an AAPI-based employee resource group for our staff to offer in-house insight and support.

Many of our offices are strategically located in neighborhoods with strong cultural identities and diverse needs, including sites in Flushing and Elmhurst, Queens, Crown Heights and East New York, Brooklyn, and Manhattan’s Chinatown. Co-located with centers of our partner, EmblemHealth Neighborhood Care, these locations treat community-specific health care needs, offer translations for written materials, and employ staff who mirror the local communities' language, cultural competency, and backgrounds.

We also work with local elected and public health officials and community leaders to increase awareness of the mental and physical health needs and challenges among AAPI populations.

As New York assesses measures to improve and deploy mental health initiatives, our medical community needs to ensure there is an open dialogue in the process that includes diverse voices. We also need to implement comprehensive plans to enhance clinical practices’ ability to care for all communities' unique behavioral health needs, especially during these difficult times. It is our time and responsibility to unite against racism, and the toll bigotry leaves on our communities.

***

Qian Gu, DO, is ACPNY Flushing North Medical Office Director. Raymond Xu, MD, is ACPNY Astoria Medical Office Director. Seth Resnick is ACPNY Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Department Chair. On Twitter @ACPNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.