New York Must Brace for a Recession; Where Things Stand and What Comes Next

Gov. Hochul talks budget (photo: Darren McGee/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul)

The Federal Reserve Board’s aggressive interest rate increases have put the nation and New York on notice that an economic downturn is a serious possibility. The Board is determined to wring inflation out of the economy, and forecasts higher unemployment but no recession. Nonetheless, New York’s leaders need to brace for one.

The nation has suffered through two vastly different recessions in the past 14 years. The COVID-19 pandemic is fresh in our memories; the Great Recession of 2008-2009 was not an economic lockdown brought on by a deadly disease, but a financial and industrial meltdown followed by a slow recovery.

In 2008 I was still in the New York State Assembly and had a bird’s eye view of New York’s escalating financial problems and our struggles to cope with them. This time around it looks like the State is far better prepared than it was then, when the State had virtually no reserves. By contrast, New York City seems less well prepared than in 2008, when it had much higher financial reserves, but its property tax base may give it the stability it needs to ride out a recession.

I wish someone would tell the Federal Reserve to stop raising interest rates and let what it has already done cool the economy rather than risk a recession, but it doesn’t look like the hawks at the Fed would listen. So what should New York do to prepare?

New York State: The First Year of Covid

New York became the nation’s epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. By the beginning of June 2020 about 30,000 New Yorkers had died of the disease. Between February 2020 and April 2020 New York State lost 1.9 million jobs, 20% of its overall employment and 23% of its private-sector employment, compared to 14% and 16% nationally, respectively.

The state government, anticipating a giant recession, adopted a budget plan in April 2020 allowing the Governor to cut up to $10 billion from the state budget and permitted New York to borrow unprecedented sums of money if necessary. A few days before the state adopted its budget, then-President Trump signed the $2 trillion CARES Act intended to preserve the economy primarily through direct relief to individuals and businesses. Then-Governor Cuomo and other leaders pressed the federal government until December 2020 to add more relief for state and local governments.

On December 27, 2020, Trump and Congress enacted a new $900 billion stimulus package, adding relief for individuals and businesses but also adding support for state and local governments, especially for education.

By March 2021, it became clear that predictions about staggering tax revenue losses in New York in 2020 turned out to be wrong. New York’s tax revenues for the 2020-21 fiscal year barely declined at all, from $82.9 billion to $82.4 billion, although the State had recovered only about 1 million of the 1.9 million jobs it lost during the lockdown.

The State’s Tax Base

It turned out New York State could have big job losses but not lose tax revenue because of its tax base. New York State obtains 60% of its revenue from the income tax.

Even as the pandemic wreaked havoc among sectors of the economy like leisure, hospitality, and retail, jobs in the affluent office sector, like finance, technology, and business services, did not suffer large declines. The office sector workforce was for the most part able to work remotely, and some still paid hefty bonuses while the wealthy continued to pay taxes on capital gains income from the stock and real estate markets. Those high incomes sustained high tax revenues even while more than a million people had lost their jobs.

The New York State income tax base is pictured in this year’s budget and shows the concentration of income and tax liability for the years 2007, 2009, and 2019, the bookends of the Great Recession and the year immediately prior to COVID, which is the last information available.

Looking at 2019 makes it clear how 2020 finances took the path they did, as well as the path the state’s finances took in the Great Recession:

The data show the extraordinary concentration of income and income tax liability in New York. In 2019, the top 1% had 29% of New York’s adjusted gross income and 50% of its non-wage income, and paid 42% of its income taxes. The top 10% had 57% of the income and 69% of the non-wage income, and paid 72% of the income taxes.

Low and middle-income residents are surely paying plenty of taxes in comparison to the levels of their incomes; when you add sales, property, social security, and income taxes together on the incomes of the middle and working classes, they are paying plenty. But the data can explain how even as one portion of the workforce is experiencing great pain, the state’s income tax revenue can hold up from another portion without job and income losses. It also shows what can happen from a recession connected to a financial meltdown, such as what occurred in the Great Recession.

The New York Budget and The Great Recession

In the adopted state budget of 2009-2010, New York closed a $20 billion deficit, $2.2 billion from 2008-9, and $17.9 billion for 2009-10.

Governor Paterson’s press release from the time of budget adoption described how the state balanced its budget: $6 billion in spending cuts; $5 billion in tax increases (mostly on the wealthy); and $6 billion in federal aid. The state had little reserves; they were a minimal factor in balancing the budget.

The Concentration of Income and Liability table above shows how a financial meltdown can affect the budget. New York’s adjusted gross income falls 17% over the two-year period (from $631 to $520 billion), non-wage income falls 38% ($270 to $167 billion), while wage income falls less than 3% ($412 to $401 billion). The crash in non-wage income is primarily the drop in capital gains. Tax payments fall, while deficits explode, because governments build budgets based on projections that plan for increased revenues and increased spending.

The Covid Recovery: Tax Revenue Rockets Up

President Biden signed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan into law on March 11, 2021. The plan included stimulus payments, state and local government financial support over several years, including a tranche of 2023 support, additional education funds, vaccine distribution funds, and other health care support.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the nation has gained 8.3 million jobs since March 2021, from 144.4 million to 152.7 million. According to the New York State Labor Department, New York State has gained 596,000 jobs, from 8.919 million to 9.515 million, with New York City accounting for 406,000 jobs, rising from 4.147 million to 4.553 million.

New York’s healthy economic growth, driven by the American Rescue plan, job increases, the boom in the stock market, Wall Street profits and bonuses, and a tax increase on the wealthy and large business enacted by the Legislature in April 2021, resulted in the state’s tax revenue taking off like a rocket.

From April 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022 (NYS Fiscal Year 2022), the state’s tax receipts grew an astonishing $22 billion, or 27%. The Governor and the Legislature responded with largess for the budget year that began in April 2022. There was a 7% school aid increase, $2 billion to backfill unpaid rent and utility bills from the pandemic, more than $1 billion for bonuses for health care workers, major funding for child care expansion, $2.5 billion in property tax relief, and gas tax relief. The State Division of Budget plan projected surpluses this year and for the next several years, and the state made a significant deposit into reserves.

New York Flush with Cash, Didn’t Spend It All

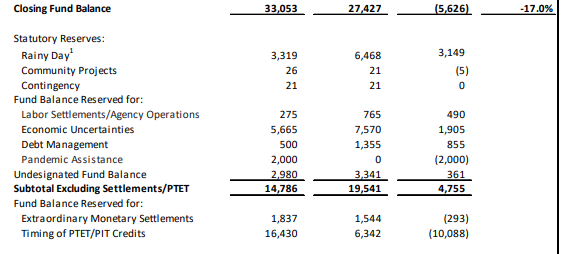

The State Budget Director, Robert Mujica, who worked for Governor Cuomo and was retained by Governor Hochul, must have had the Great Recession in mind when planning for the state FY2023 budget. The Legislature was persuaded to save billions from the surplus cash that flowed into the State Treasury in 2021. As of this July, the state was so flush that it anticipated having a cash balance of $27 billion in the General Fund by March 2023, of which $19.5 billion could be accessible for an emergency, excluding special obligations. See NYSDOB, 1st Qtr. Update, p.25:

FY’22 FY’23

A New Recession in New York May Be Like 2008-09

The Federal Reserve’s hawkish actions to curb inflation upended the Division of the Budget’s rosy projections within just a few months. The State DOB’s First Quarterly Update (April-June 2022) recognized the Federal Reserve’s actions to slow the economy would halt the revenue boom. Surpluses would turn to deficits and next year, FY 2024, would see a $3 billion deficit. Deficits in future years would grow. The update was written in August, before the Federal Reserve’s next big interest rate increase, and the DOB will surely increase the size of the state’s deficits next year and beyond due to the slowing economy.

Big stock market declines, plunging Wall Street bonuses, and a drop in real estate transactions mean big tax revenue losses even if job losses are modest because the wealthy already pay such a large share of New York’s taxes. Even in a recession, they stay wealthy, their incomes just decline temporarily. But that’s why a recession in New York could be similar to 2008-2009. This time New York is fortunate all that cash is sitting in reserve funds.The state will need the reserves to mitigate the economic impact of the downturn and preserve services, especially if there are no new federal funds for another bailout of state and local government.

What To Do

-Substitute Borrowing for Use of Cash in Capital Projects

The state plans to transfer $4 billion in cash in 2023 and $6 billion in 2024 to avoid selling long-term bonds to pay for capital projects, a large increase in the use of cash for capital projects compared to past years. This is prudent but the state doesn’t have to do this. It is discretionary.

The cash could be used to support the operating budget if necessary during a recession. Borrowing several billion is not a bad thing, capital projects are appropriate uses of borrowed funds. The state could also defer certain capital projects to preserve cash.

The state also has the ability to borrow short-term for operating purposes, as long as the money is repaid by the end of the fiscal year. If necessary, the state could borrow several billion next spring to cushion spending as the economy is monitored. It could use its reserves to repay the money at the end of the year.

-Use the Reserves, That’s Why They’re There

The State has enough flexibility to use $5 billion a year, even for more than one year, to protect services. Obviously it would be unwise to use all of the reserves.

-Use Federal Aid from the American Rescue Plan

A third and fourth year of federal support for state and local government provides $2.4 billion in 2024 and $2.3 billion in 2025. The state can use these funds as it wishes, including simply shoring up its existing budget.

-Postpone, Even Modestly, Planned Spending Increases

The state cannot really hide completely from a downturn that results in lower revenues. It has planned a $3 billion (10%) increase in school aid in 2024 to strengthen Foundation Aid. It can stretch that out further. The state’s child care expansion is only $100 million extra in 2024 and that should be sustained; it is not very costly.

New York City and Recession

New York City has now recovered 85% of the jobs lost during the lockdown, not as high as the nation, but it lost 23% of its employment in the lockdown, compared to 14% nationally so it has had much further to go to recover. It would be a shame if Federal Reserve actions thwart the city’s recovery.

The healthy recovery enabled the city to use $6 billion in surpluses to prepay expenses for this fiscal year, which began July 1. However, federal aid this year (FY 2023) has dropped closer to normal, $9 billion. As a result, surplus cash is likely to be unavailable next year and the projection is that the city will have a $4 billion deficit. This was the projection at budget time before the Federal Reserve Board’s aggressive actions.

State Comptroller DiNapoli’s August 2022 report on New York City’s Financial Plan warned that risks to the city’s budget could increase the city’s deficit next year to $6 billion (some of which appears to be an unavoidable pension shortfall of $870 million).

The comptroller’s report indicated that a recession similar to 2009 could result in $4 billion in revenue losses to the city next year. Both the comptroller and the Citizens Budget Commission have been urging the city to build its reserves, which are lower proportionately than what the city had available in 2009. Mayor Adams is implementing a Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG), curtailing spending now across city agencies.

The city’s newest fiscal challenges, from Texas sending refugees to the state mandating class size reductions for the school system, call out for state and federal help, especially given the risk of a recession. The city has one backbone for revenue: the property tax, which historically has held up even in downturns.

The city has $8 billion in reserves and, as a last resort, could enact a highly unpopular property tax increase. The city needs to maintain, even increase, its capital program and invest even more funds in affordable housing and conversion of office space to residential. During the next state budget process, Mayor Adams will need a truly focused effort to get the state to acknowledge the need to help its largest city.

In the Great Recession, the breakdown of the state budget lasted three years, from 2008-2011, in major part because it had no reserves to fall back on. This time, the state may be able to manage a soft landing in New York, even while the rest of the country has more problems than we do.

***

Jim Brennan was a member of the New York State Assembly for 32 years, where he chaired four committees. On Twitter @JimBrennanNY.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York's Opportunity to Purchase: Help Stabilized Renters Buy Their Buildings

Affordable housing (photo: Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office)

Rent increases begin for roughly one million rent-stabilized New York City apartments on October 1, the highest increases since 2013.

Fallout from the pandemic has strained landlords, especially owners of smaller multi-family rental buildings, and it has also dramatically impacted families who were already struggling to pay even below-market-rate rents.

At the “raucous” Rent Guidelines Board meeting about the increases, tenants advocated for rent freezes and rollbacks while landlords argued for higher increases.

Here is a strategy for our city to help both landlords and tenants: create opportunities for rent-stabilized New Yorkers to buy their buildings.

Converting existing rental buildings into shared equity homeownership opportunities will enable renters to experience the generational wealth, health, and educational benefits of home equity. Owners who are already thinking about selling will have an opportunity to do so in a way that delivers dollars and social impact, strengthening our city.

As I gathered with world leaders recently as a delegate to the Clinton Global Initiative, I was honored to introduce the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Program (TOPP) as our “commitment to action.” TOPP will convert 350 rental apartments into permanently affordable homeownership opportunities on a community land trust, providing access to homeownership for future generations of low-income New Yorkers.

Through TOPP, tenants and multifamily building owners will access technical assistance, housing finance, and construction preservation expertise. It’s a win/win/win scenario that is scalable as a model for all like-minded, mission-driven businesses and organizations to transform tenants into owners.

Affordable homeownership is a uniquely powerful tool for creating more equitable communities. It creates community assets that protect families from displacement, immune to the vagaries of speculative investment.

It offers self-determination of where to live and how long to stay.

It fosters more civically-engaged residents, and, through rental-to-ownership conversions, provides opportunities to make energy efficiency improvements to mitigate climate change and reduce energy costs.

Perhaps most importantly, affordable homeownership creates infrastructure for equity, as an urgent response to centuries of racist housing laws and financing mechanisms that prevented communities of color from entering the homeownership market. This legacy continues to shape the geography of the wealth, health, and education inequality we see today in our city where 41% of white people own homes, while only 27% of Black people and 16% of Latino people do.

We estimate that roughly 95% of tenants who will become homeowners through TOPP will be Black or Latino New Yorkers in communities that have lengthy histories of disinvestment and redlining. With well-resourced investors buying potential starter homes as they hit the market and converting them to market-rate rentals—and with affordable housing construction focused almost exclusively on rental housing—now is the vital time to implement new homeownership strategies to close the racial homeownership gap.

By addressing housing affordability and equity through affordable homeownership conversions, we as a city can build a more equitable New York, addressing several of our most pressing social and economic challenges at once.

***

Karen Haycox is CEO of Habitat for Humanity New York City and Westchester County. On Twitter @HabitatNYC_WC.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

The MTA Must Fix Its Defective Assessment of Congestion Pricing

Clearer streets on the way (photo: Marc A. Hermann/MTA New York City Transit)

Damage continues to mount from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s bungled environmental assessment (EA) of congestion pricing.

With its sprawling, 46-volume EA, the MTA took a proven policy idea, so well-suited for New York that it was destined to bestow $10 million worth of travel-time savings to drivers across the region every day, and turned it into a dog: a money grab that will cut traffic only in Manhattan.

While that “finding” is nonsense, it has a whiff of plausibility. Congestion pricing will cause some car and truck trips that now go through Manhattan from New Jersey to Long Island to divert around the island. Some will go west to east via the Bronx, others will divert to the south, across Staten Island. But the MTA has grossly exaggerated this effect.

According to my new analysis, the authority has also understated this offsetting effect: the tolls will result in elimination of 10 to 15% of auto trips from around the region that now go to the Manhattan core, and that habitually congest the boroughs and counties through which they pass en route.

These errors add up to an average five-fold underestimate in the EA of cuts in traffic volumes outside the Manhattan core because of congestion pricing. For the bulk of the region — the four “other” boroughs plus Westchester, most of Long Island, and the closest New Jersey counties (Essex and Hudson) — traffic volumes will fall by an average of 2%, a palpable cut, rather than the EA’s nothingburger forecast of 0.4%.

Put differently, for every vehicle-mile of car traffic that congestion pricing will eliminate within the Manhattan pricing zone, eight vehicle-miles will disappear outside the zone.

Were these findings in the assessment, the storm of criticism of congestion pricing since the EA’s August 10 release would have been far less intense. Instead, as the final push approaches, congestion pricing has seemed at times to be shedding public support. And no wonder. For a wonky, seemingly newfangled scheme like congestion pricing to actually come into being, it must bring big, broad benefits, not perks for a small and relatively wealthy minority.

Making matters still worse, the face of the assessment, and thus of congestion pricing itself, soon became its forecast of more heavy trucks spewing exhaust on and around the poster child of transportation injustice, Robert Moses’ Cross-Bronx Expressway. Yet the fact is that even with such an increase, the Bronx as a whole would still enjoy slightly cleaner air due to lesser atmospheric conversion of regional exhaust into toxic particles. Even better, the shrinkage in traffic volumes promises to cut air pollution across the board as fewer combustion engines spew emissions, fewer vehicle tires are ground into airborne particulates, and trucks’ driving speeds even out somewhat with improved traffic.

The prospect of lower traffic volumes throughout the region puts the lie to the idea that only residents of Manhattan stand to benefit from congestion pricing. True, the proportional fall in traffic volumes will be most pronounced in Manhattan, but traffic volumes region-wide will shrink so much that the reductions outside the zone will far exceed the reductions within it — again, by eight-fold, per my calculations.

This finding also refutes the idea that congestion pricing is “only about the revenue.” Rather, congestion pricing will not only raise revenue to improve subway service — the economic lifeblood and equity linchpin of our city and region — it will materially cut traffic, even without crediting the “carrot” effect of better mass transit luring some trips from automobiles.

How Did the MTA Get Congestion Pricing’s Traffic Benefits Wrong?

Following the August 10 release of the MTA’s environmental assessment, I tried for weeks to ferret out the “price elasticity” in the “best practices model” (BPM) the authority used to estimate how congestion pricing will change traffic and travel.

I theorized that the BPM grossly understates the extent to which making it costlier to drive into or through Manhattan will induce drivers to “mode-switch” to public transit or carpool or give up the trip altogether. I also wondered if MTA staff running the model had mathematically misapplied price-elasticity in a way that would compound the undercount of eliminated car trips.

I came up empty. The MTA modelers ignored my entreaties to share info, and their model, a product of the age of mainframe computers, is impenetrable. However, I learned last week from a source that the BPM does not even employ price-elasticity, which translates percentage increases in trip costs into percentage decreases in trip volumes. It may instead model trip choice through the physics concept known as “impedance,” treating tolls and other trip costs in a manner analogous to increased resistance to electric current flowing through a wire.

Somehow, this got me thinking differently about the MTA’s modeling. If the big flaw in the environmental assessment was that it understated traffic reductions outside of Manhattan, I would try to calculate how congestion pricing would change “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) in those areas.

My Qualifications to Assess Congestion Pricing

Since I am counter-posing the MTA’s congestion pricing findings with my own, I should state my qualifications to quantify congestion pricing’s impacts.

I have spent much of the past 15 years developing and updating an elaborate (“kaleidoscopic,” I like to say) Excel spreadsheet model of New York City traffic and transportation known as the Balanced Transportation Analyzer.

The “BTA,” which I continually update and keep in the public domain via this permalink, has over 80 interlocking worksheet “tabs” that are stocked with baseline travel data and connected by over 100,000 equations and algorithms. These tabs “communicate” with each other and recalculate traffic volumes and other outputs whenever users enter inputs that correspond to congestion tolls and/or dozens of other potential policy changes. Data inputs are made easily in a single tab, allowing them to be processed in minutes or even seconds, and the calculation of results is instantaneous.

The BTA’s rigor and its ability to output the impacts of policy changes such as congestion toll levels led to its being made the primary analytical tool used by New York State’s “Fix NYC” panel to scope congestion pricing in 2017-2018. (The Fix NYC panel report has been scrubbed from New York State government sites but is archived at my website; the report’s Appendix B dedicates two pages (pp 32-33) to describing and lauding the BTA.)

To my surprise, this year the MTA’s environmental assessment team used my spreadsheet to select the toll levels it then evaluated for its various tolling scenarios. (See Central Business District (CBD) Tolling Program, Appendix 4B.1, Transportation: Transportation and Traffic Methodology for NEPA Evaluation, p. 1-2.) The team did not, however, use the BTA to estimate the number of auto trips to or through the congestion zone that would be eliminated under the different toll scenarios.

My VMT Analysis of Congestion Pricing

Conceptually, my analysis was simple: I drew on the estimates in the BTA of two categories of daily auto trips: (i) those that presently “land in” the congestion zone, or central business district (CBD), and (ii) those that drive through the CBD, from west of the Hudson River (New Jersey) to geographic Long Island, i.e., the boroughs and counties east of the East River (Brooklyn, Queens, Nassau, Suffolk), or vice-versa. From the latter figure, through-trips, I was able to estimate the number of auto trips with similar origins and destinations (NJ to east of the East River, or vice versa) that drive around rather than through the Manhattan core.

How did I estimate the number of auto trips that now, without congestion pricing, drive around the zone? I compared the costs of a typical trip through the zone to one around it, accounting for fuel costs and travel time (both of which are calculated from assumed trip distances), as well as any pre-existing tolls, such as the Port Authority tolls to travel eastbound through the Lincoln or Holland Tunnel or over the George Washington Bridge.

By constructing probability distributions around these mean costs, I was able to calculate that, under present conditions, out of every 100 trips with those origins and destinations, the less expensive route is through the zone for 56 trips, and is around the zone for the other 44. I then posited that trips seeking to go from New Jersey to Brooklyn/Queens/Long Island (or vice versa) adhere to those proportions, meaning that, without congestion pricing, 56% of those trips go through the Manhattan congestion zone while the remaining 44% go around.

I then “perturbed” my baseline assumptions of driving speeds (and, thus, travel times) and tolls to reflect prospective changes from congestion pricing. The result was that the share of trips from west of the Hudson to east of the East River (or vice versa) that will find it less expensive to go around the zone increased to 48%.

Translated to trip volumes, this 4 percentage point rise in the share of go-around trips equates to 11,400 additional trips “diverting” around the congestion zone per day, as shown in Table 1 below.

That is only part of the congestion pricing equation, however. The other, and arguably more impactful part, is the outright elimination of auto trips (and not just their rerouting) as the congestion toll pushes some trips “underwater” economically, in that the net value of the auto trip for the trip-taker turns negative. These trips may switch to train, bus, subway, bike, walk, carpool, new destination, or no destination (i.e., the trip is canceled).

For my calculations I assumed that 1/8 of the auto trips that currently land in the congestion zone will be so eliminated, with a somewhat smaller fraction, 1/10, of west-of-zone to east-of-zone (and vice versa) auto trips being eliminated. The 1/8 figure is consistent with my congestion pricing modeling for trips bound for the zone; the lower 1/10 figure takes into account the poorer transit alternatives for trips that pass through or go around the congestion zone, while also reflecting the fact that trips landing outside the Manhattan core tend to create less economic value for motorists, rendering them more vulnerable to the impact of the congestion toll than trips bound for the zone itself.

These assumptions result in the before-and-after volumes of trips that pertain to the congestion zone, either by landing in it or going through or around it, shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Daily Auto trips that relate to the Manhattan Congestion Zone

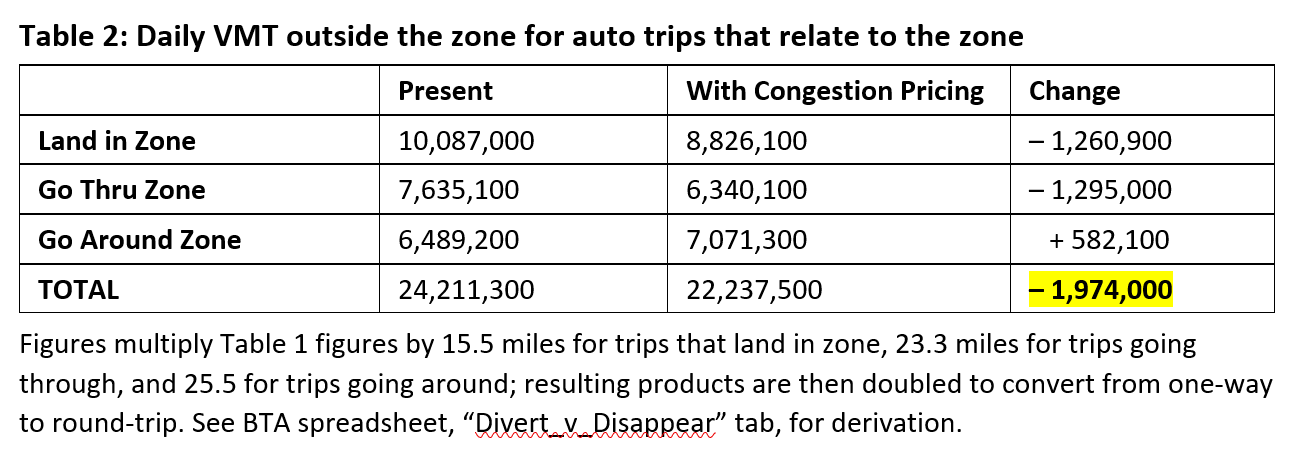

Table 1 is only an intermediate result. The goal is the changes in non-CBD (non-zone) mileage for each category of trip. These are shown in Table 2:

Table 2: Daily VMT outside the zone for auto trips that relate to the zone

The literal bottom line in Table 2 indicates that congestion pricing will result in 1,974,000 fewer daily miles traveled by automobiles outside of the Manhattan congestion zone. The 582,100 daily increase in VMT from the uptick in trip diversions around the zone is swamped by the combined 2,555,900 decrease in VMT stemming from the elimination of trips to and through the congestion zone.

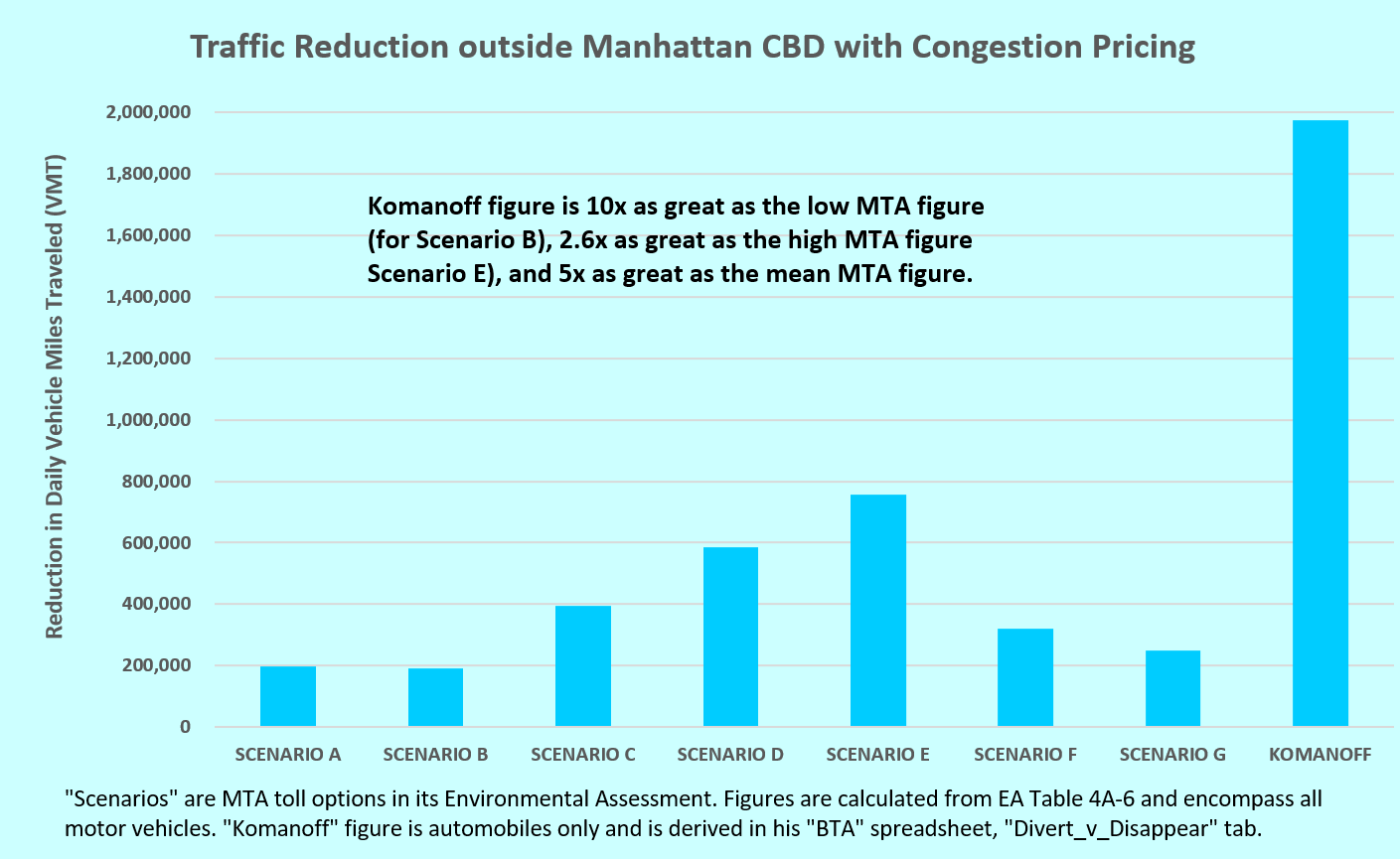

Now consider the projections in the environmental assessment (EA) for reduced VMT outside the zone. These range from a low of roughly 190,000 (Toll Scenario B) to a high of 760,000 (Toll Scenario E) and average 385,000 (Toll Scenarios A-G). I computed those figures directly from the Environmental Assessment’s Table 4A-6: Daily Vehicle-Miles Traveled: No Action Alternative and CBD Tolling Alternative, by Tolling Scenario (2023).

My estimate of the reduction in VMT outside the congestion zone, 1,974,000 miles per day, is 2.6 times as great as the EA’s high figure, 10 times as great as the low figure, and 5 times as great as the mean.

The Meaning of 2 Million Fewer Miles Driven Outside the Zone Each Day

My estimate, nearly 2 million fewer daily auto miles driven outside the congestion zone, is hard to grasp. To put it in perspective, consider that the combined present-day automobile VMT for New York City (outside of the congestion zone) plus most of Long Island, all of Westchester County, and the New Jersey counties closest to the CBD (Hudson and Essex) is around 100 million. (That figure is rough-calculated from Table 4A-6 in the EA.) Since most auto trips into and through the CBD originate from those districts, it’s fair to say that my estimate of just under 2 million miles a day of reduced auto VMT outside the zone equates to nearly 2% of current auto traffic in those areas.

An average 2% reduction in traffic volumes outside the congestion zone is no small thing. It promises cleaner air, quieter and safer streets, and faster, easier travel for motorists and truckers. Indeed, that promise is a key part of the bedrock on which congestion pricing advocacy has been built.

Refuting the Notion that Congestion Pricing is Manhattan-Centric

The same EA Table 4A-6 referenced above gives the MTA’s projected reductions in VMT inside the congestion zone for the seven toll scenarios. These average around 250,000 miles per day. Compared to that figure, my estimate of nearly 2,000,000 fewer vehicle miles traveled outside the zone is around eight times as great.

While there is an element of apples/oranges to this comparison (the 250,000 figure employs the MTA’s methodology whereas the 2,000,000 figure arises from mine), the contrast is so stark that it should dispel the notion that only residents of Manhattan stand to receive congestion pricing’s bounty of lesser traffic.

A Caveat

In analyzing before-and-after cost-preferences for driving through versus around the congestion zone, I chose to add only $5 to the tolls that motorists driving into Manhattan via the Holland or Lincoln Tunnels will face with congestion pricing.

That figure is intended as a rough true-up of the current Port Authority tolls to cross the Hudson River ($13.75 peak, $11.75 off-peak) to the eventual congestion toll that will likely be $15 or somewhat higher. In other words, I have chosen to assume that the congestion toll won’t be applied in its entirety on top of the incumbent Port Authority tolls.

Nevertheless, relaxing that assumption by adding $15 rather than $5 in congestion tolls to the two Hudson River tunnel crossings reduces the calculated reduction in non-CBD VMT from congestion pricing by only 10%: to a little under 1.8 million from a little under 2 million. It thus appears that my finding of substantially less VMT outside Manhattan is not terribly sensitive to my assumption that motorists crossing into Manhattan via the Port Authority tunnels won’t face the entire congestion toll as an increment in the price of their trip.

An Invitation

My key result, that congestion pricing will shrink daily VMT outside the congestion zone by nearly 2 million miles, is of course an artifact of assumptions as to toll rates, the value of motorists’ time, distances covered, highway and street speeds, etc.

I invite readers to input their own assumptions and see how the calculated VMT result changes. Unlike the MTA’s Best Practices Model, my BTA spreadsheet is in the public domain and is easily manipulable for the sake of sensitivity analysis. As noted the BTA is available for downloading (17 MB Excel spreadsheet, go to “Divert_v_Disappear” tab).

In Closing

Congestion pricing was always going to have to be fought for, every step of the way, not only to enact the legal authority, as was accomplished in the New York State Legislature’s March 2019 budget bill, but to actually put it into practice. We advocates were ready to help ensure that the congestion toll program was put into fruition. However, we should not have had to help beat back the tidal wave of opposition that has engulfed the program since the MTA’s environmental assessment was released, which arose largely from the assessment’s faulty modeling and unfounded results.

Those results should be withdrawn. Contrary to the MTA’s assessment, not just the Manhattan core but the entire city and region are poised to enjoy material reductions in traffic volumes and, with them, the panoply of economic and quality of life benefits that congestion pricing proponents have long touted to our fellow New Yorkers: quieter, safer streets; more accommodating environments to walk and bike; cleaner air; speedier bus service; easier goods logistics and delivery; and, above all, improved travel times for users of automobiles, yellow cabs, ride-hail services, buses, and trucks.

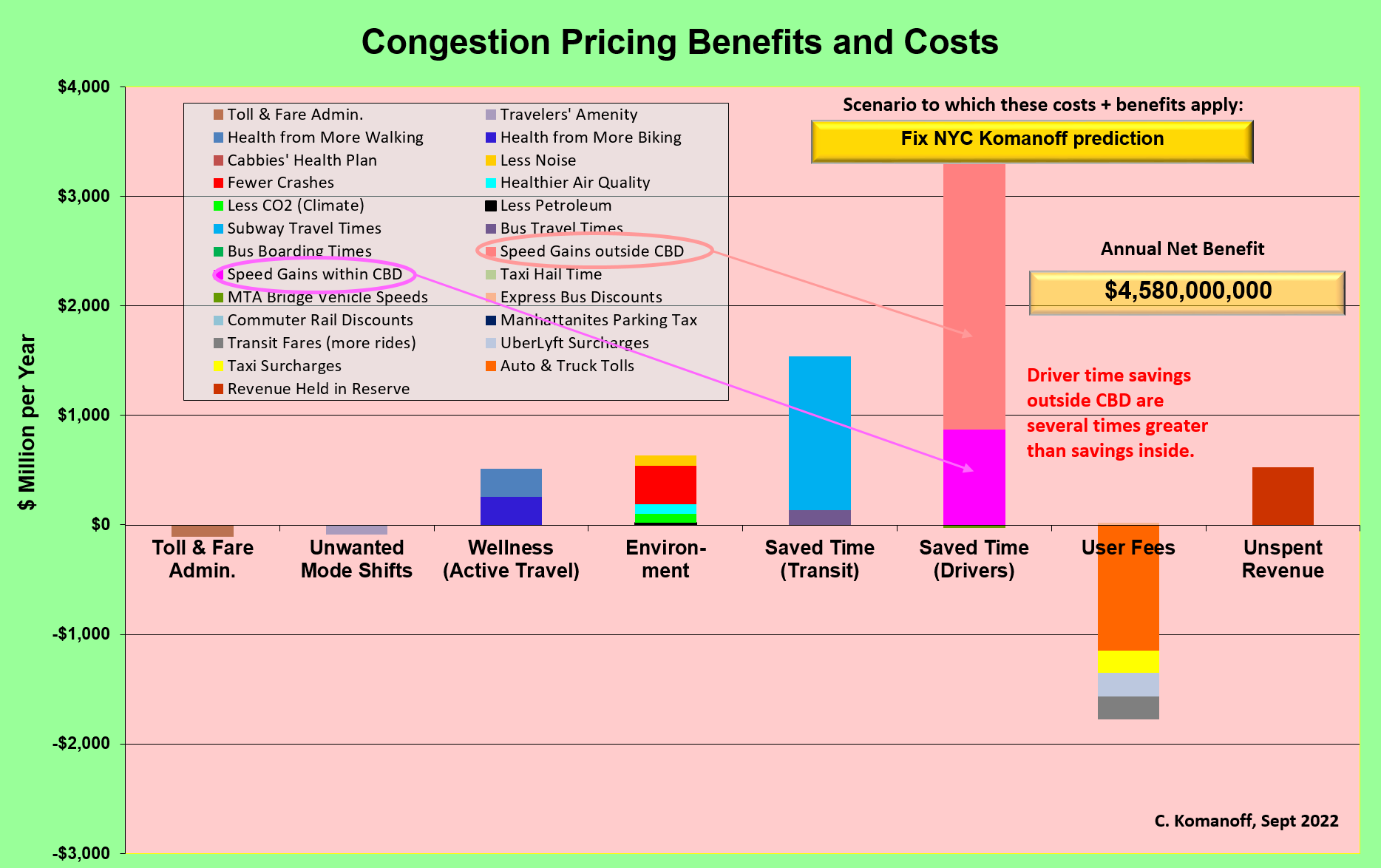

My own modeling puts these “net” benefits (“net” in the sense of deducting the tolls paid by motorists, the cost to install and operate the tolling infrastructure, and the lost value of the trips that the new toll will “price off the road”) at some $4.5 billion a year — around $12.5 million a day. Denying that benefit, as the MTA’s environmental assessment essentially does, by grossly undercounting traffic reductions across the city and region, qualifies as an “own goal” of monstrous proportions. I call on the MTA to reboot its analysis and finish the job of leading congestion pricing through the bureaucratic wilderness and to fruition as soon as possible.

***

Charles Komanoff, long-time New York policy analyst and environmental activist, has been quantifying congestion pricing's costs and benefits for 15 years. On Twitter @Komanoff.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.