To Truly Pursue Equity in Marijuana Rollout, Cannabis NYC Needs a Makeover

Announcing 'Cannabis NYC' (photo: Ed Reed/Mayoral Photography Office)

It’s no secret that the War on Drugs has disproportionately impacted people of color in the United States, leading to the scourge of mass incarceration. In 2010, the ACLU released an analysis on cannabis convictions, showing that Black people in New York state were 4.5 times more likely to get arrested for possession of cannabis than white people even though both groups use it at the same rate. Ten years later, this phenomenon hasn’t changed. In 2020, the NYPD’s crime statistics data reported that people of color in NYC made up 94% of arrests and summonses issued for low level cannabis violations.

It has been over a year and a half since cannabis was legalized in New York. Heralded as the most equitable cannabis legalization effort in the United States, the Marijuana Regulation & Taxation Act (MRTA) focuses on groups that were impacted the most by cannabis prohibition – namely black and brown communities. However, NYC’s program, Cannabis NYC, has not invested nearly enough into communities that have been hurt the most by cannabis prohibition. As New York state implements its recreational cannabis licensing process with the first 36 licenses, and NYC provides a meager $4.8 million investment through its program Cannabis NYC, we must ask ourselves: is this really the best we can do?

In theory, New York state has instituted impressive measures to uplift social equity entrepreneurs, or individuals with prior cannabis-related convictions seeking to open a recreational cannabis business. Some of these initiatives include setting aside 50% of licenses for social equity entrepreneurs to open recreational dispensaries and a $200 million investment fund that will underwrite costs associated with leasing retail spaces and loan assistance. Despite the support on paper, the administration is moving too slowly in practice. The aforementioned retail spaces have not yet been secured and the fund has not raised the promised $150 million in seed funding. With Governor Hochul’s announcement that only 36 legal cannabis dispensaries will be in operation by the end of the year, there is reason to worry about how social equity entrepreneurs will be supported in this disorganized plan.

On the city side, there have been insufficient investments in social equity entrepreneurs. The Adams administration created and tasked Cannabis NYC with providing services including license application assistance, outreach to communities that are eligible to apply for social equity licenses, and workforce development training for the cannabis sector. Even with these minimal responsibilities, Cannabis NYC barely fits the bill. Since Cannabis NYC was only established three months ago, most of the application support was falling on the shoulders of nonprofits and law firms, sometimes costing individuals up to $10,000 in fees.

Additionally, cannabis businesses are a costly endeavor with a $2,000 application fee for a recreational license and high-cost barrier to enter the industry. Start-up costs for retailers can range between $250,000 - $750,000. The Drug Policy Alliance found that in 2019, the city spent almost $100 million alone on policing drug arrests and violations. As reparations for these egregious oppressive measures, Cannabis NYC must expand its supportive services to provide financial assistance to social equity entrepreneurs to cover the recreational cannabis license fee of $2,000

and underwrite a fraction of the start-up fees when the state inevitably moves too slowly to provide assistance. Cannabis NYC must also bolster their application assistance for all New Yorkers seeking their services.

The recent increase in crime may make New Yorkers less sympathetic toward those with prior convictions, leading them to object to additional supportive measures. In a recent poll, 70% of New Yorkers reported concern about feeling less safe since the pandemic due to increased crime rates. However, research has shown that access to employment is the most important factor in reducing recidivism. Even for individuals who do not support cannabis usage, an investment in communities with past convictions will keep them out of the cycle of crime and the prison system, thereby reducing crime rates across the city.

The NYC Comptroller office projected that revenue from cannabis sales in NYC could reach as much as $336 million per year. In a city where the operating budget is $101 billion, this may seem like a drop in the bucket. However, when put into perspective, this amount shows how much NYC will gain from the cannabis industry, while investing just over 1% of projected revenues in social equity entrepreneurs who have been harmed by the city’s criminalization of cannabis. As reparations for the damages that cannabis prohibition ravaged upon Black and Brown communities in NYC, the mayoral administration must ensure social equity entrepreneurs make their mark in this highly profitable industry. One small step is by increasing financial support to social equity entrepreneurs through underwriting their start up business costs and covering the $2,000 retail dispensary license application fee.

***

Arielle Kaye is an MPA student at NYU specializing in International Development Policy & Management.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Reason to be Thankful This Holiday Season: New Law Empowers Sexual Assault Survivors

Gov. Hochul signs the Adult Survivors Act (photo: Mike Groll/Governor's Office)

On Thanksgiving, survivors of sexual abuse in New York had something to be truly thankful for. November 24 marked the opening of a one-year period when, under a new law, survivors can file a civil claim against the person who abused them and any institutions that enabled the abuse, no matter how long ago the abuse happened.

This law, the New York Adult Survivors Act (ASA), presents a watershed moment for survivors; it invites and empowers them to reclaim their narratives, end their silence, and hold those who harmed them accountable.

The ASA was born of the recognition that for too long, survivors of sexual abuse were either disbelieved, shamed, or blamed for the abuse and left with little support to recover from the trauma left in its wake. After all, until 1984 it was legal in New York for a husband to rape his wife. And sexual harassment was not even considered a violation of federal civil rights law until 1986. Even once the laws became more protective of survivors, historically short statute of limitations periods meant that by the time survivors were able to speak their truth, it was often too late to sue the abuser. In reviving expired claims, the ASA also revives survivors’ chances for a measure of justice and acknowledges the reality that processing sexual trauma takes time.

Ending silence, secrecy, and shame around abuse is why laws like the ASA, the Child Victims Act before it, and the anti-SLAPP law New York passed in 2020, are so important. SLAPP lawsuits (or Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) have long been used by abusers to torment and silence survivors. Formally named in the 1980s and in use well before that, a SLAPP suit may look like an ordinary claim for defamation, nuisance, or invasion of privacy but its purpose is to intimidate and muzzle the person on the other side. Abusers leverage SLAPP lawsuits to tie up survivors in lengthy legal proceedings in an attempt to drain them of their financial and emotional resources while fighting these baseless claims.

This tool was famously used by Johnny Depp against Amber Heard to punish her for publicly telling her story of intimate partner violence in the Washington Post, leaving her silenced and impoverished in the end. The publicity surrounding that case has undoubtedly had a chilling effect on survivors considering coming forward to speak out about the abuse they suffered, especially if their abuser is famous, powerful, or rich.

The SLAPP suit is also the tool that was wielded against me (Grace) by my ex-husband, who sued me for defamation after I spoke out on my podcast about abuse in the entertainment industry and the challenges facing victims in the justice system. But thanks to New York’s anti-SLAPP law, my story has a happier ending than Amber’s: earlier this month, a court threw out the lawsuit against me and ordered my ex-husband to pay the attorney fees and costs I incurred while defending myself.

For too long, short statutes of limitations for filing abuse claims and the threat of SLAPP lawsuits conspired to keep survivors quiet. And that silence only benefited abusers, allowing many to suffer no consequences and go on to abuse others. But taken together, New York’s anti-SLAPP statute and the one-year Adult Survivors Act revival period create the opportunity for a full-throated telling of survivors’ stories to fill the courts with accountability as its final chapter. And that is something to be thankful for.

***

Grace Aki is an actor, playwright, and comedian in New York. Laura Edidin is Of Counsel at Wigdor LLP, a former sex crimes prosecutor, and domestic violence victim advocate. On Twitter @itsgraceaki & @WigdorLaw.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

New York Universities, It’s Time to Tear Down That Wall

Fordham University behind the wall (photo: Brian Martindale)

New York universities are walling people out. Major private institutions across the city are surrounded by gates, but not because they are in the most dangerous neighborhoods. Rather, it appears that largely white student bodies are being walled off from their surrounding communities because of unfounded fear of racial others.

Columbia University, in a neighborhood adjacent to Central Harlem, is blockaded on every side with a security force keeping watch on all who enter its narrow gates. St. John’s University, in Queens’ Hillcrest neighborhood, is peppered with turnstiles, gated parking lots, and signs marking it as “Private Property.” Fordham University’s Rose Hill campus in the Bronx is similarly locked-down, separated from the surrounding community by wrought iron and chain link fences, at places with barbed wire and stone walls. The only way in, with few exceptions, is by scanning a school ID past a staffed security booth or full-height turnstiles.

Standing in contrast is New York University, located in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. NYU is a decidedly urban campus, built into the fabric of the city, with the public Washington Square Park serving as its primary quad.

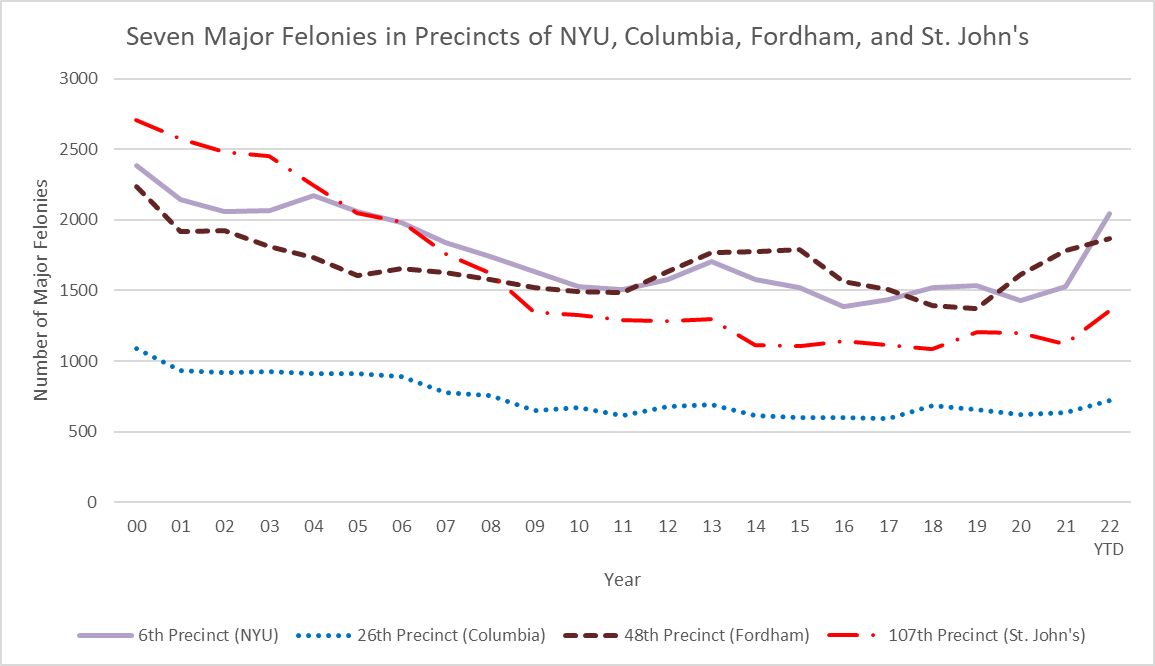

What makes NYU different? Gut instinct might suggest NYU is in a safer neighborhood so it doesn’t need a gate. But it turns out the universities that believe they need to wall out crime are actually in safer communities. A quick look at crime statistics since 2000 shows that among the four universities, NYU’s precinct has had the highest or second highest number of major felonies every year. The area around Columbia has had half as many major crimes as the area near NYU every year for the last 22. This year, NYU is on pace to have the highest crime again, with 2,045 major felonies as of November 13, compared to 1,869; 1,357; and 720 for Fordham Rose Hill, St. John’s, and Columbia, respectively. If NYU can manage without a wall, the others can as well.

There is, however, a key factor that distinguishes NYU from the three other universities: the racial makeup of the neighborhood. In 2019, Greenwich Village/Soho was 14% Black and Hispanic, while Columbia and Fordham are in neighborhoods that are majority Black and Hispanic. St. John’s is in a neighborhood that is 37% Black or Hispanic and also has a significant Asian population, at 31% of residents.

It is no secret that perceptions of safety are often related to race. A 2001 article by researchers at Florida State University suggests the presence of racial “others” lead to greater fear of crime, and another 2018 article suggests such “white fear” leads to continuing racial segregation. The universities in predominately non-white neighborhoods, though they are safer, appear to be using walls to shut out their neighbors because of this fear.

The shutting-out also shows itself in university enrollment. While 96% of Fordham’s Bronx neighborhood is Black or Hispanic, only 18% of its Bronx campus students were Black or Hispanic in 2020. Columbia had a mere 13% Black or Hispanic population at its Morningside Heights campus in 2020 compared with 52% in the neighborhood. St. John’s Queens campus is closer, with 31% Black or Hispanic students compared to 37% in the neighborhood, but Asian representation is only 16% compared with 31% of neighborhood residents.

These disparities are significant. They mean that the walls are working.

But what’s the big deal anyway? Why should anyone care if college campuses bar their neighbors from entering? Isn’t it better to wall off the students and keep adolescent antics from bothering neighborhood residents?

While some imagine benefits, walls correspond to serious setbacks for neighborhood development. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, urbanist Jane Jacobs writes of boundaries in cities as “barriers,” creating “vacuums.” They set in motion “an unbuilding, or running down process.” If people can't walk through an area because of a university wall, they won’t shop at the stores nearby or visit the amenities. Stores close, sidewalks become empty, and safety decreases with fewer eyes on the street. Campus walls aren’t neutral in their neighborhoods. They actively oppose economic development and public safety.

A short walk up Amsterdam Avenue toward Columbia’s campus can show what happens to a university isolated from its neighborhood. Just south of campus, Amsterdam is vibrant, with shops and restaurants and people strolling the sidewalk. Parks and churches dot the avenue. But as you get closer to campus, the stores and restaurants are replaced with imposing walls and the sidewalks become lonely. As you continue past campus, the vitality reemerges. But beware: if you turn down 120th Street, along Columbia’s northern wall, the same loneliness awaits you. The campus barrier smothers development, and if it were removed the neighborhood would have breathing room to improve further.

What’s even more concerning than neighborhood vitality is the educational opportunity these walls prevent. By sending the message that neighborhood residents do not belong on prestigious college campuses, the walls are minimizing the possibility of upward mobility that accompanies such education, continuing the cycle of poverty so often persistent in non-white communities. The United States has always had racial disparities in higher education, with an unfair number of white students able to attend college compared with Black and Hispanic students. While the gap between who starts college is decreasing, there are increasing racial gaps in who achieves a college degree in the U.S.

There are also gaps in the quality of college that people of different races attend. Columbia, Fordham, and St. John’s are among the best-ranked private institutions in New York City. The racial disparities that persist because of their literal and figurative walls are not blocking students from just any college education. Walls prevent under-resourced populations from the education with the most possibility for economic uplift, especially as compared with two-year programs and community colleges.

Even if the walls don’t come down tomorrow, these universities owe it to their neighborhoods to be active and supportive agents to tear down the invisible walls that separate the institutions from their neighborhoods. They should use local vendors for university needs to support the wellbeing of neighbor businesses. They should invite community members to be a part of meetings with politicians or other power players that come to speak on campus.

They should leverage their influence to advocate for the needs of their neighborhoods, and to do so they must really know their neighbors. They need more educational support programs like CSTEP to support non-white and economically disadvantaged students, especially from the nearby community. While these institutions have made strides in this area, more must be done.

Then, it’s time to tear down the physical walls. We ought to be doing everything we can to help students of color envision themselves at our institutions of higher education. Because if they can’t even imagine walking the campus, how could they ever imagine walking the graduation stage?

***

Brian Martindale is a Jesuit seminarian and master’s student in urban studies at Fordham University.

***

Have an op-ed idea or submission for Gotham Gazette? Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.