When the Metropolitan Transportation Authority released its budget proposals this summer, the newspaper headlines focused on the proposed fare and toll increases. But more general funding and service issues loom just as large.

The MTA proposed a $6 increase in the $70 monthly unlimited ride MetroCards and a $3 increase in the $21 weekly passes. It also proposed a 50-cent increase in tunnel tolls (currently $3.50) and a $2 increase in the $4 fare for express buses. Metro-North and Long Island Rail Road fares would rise by about five percent. The fare and toll increases and cutbacks in some transit services will be voted on by the MTA Board in December and take effect sometime in 2005. The base subway fare of $2 would be unchanged, as would the discounts for buying at least $10 in fare value at a time.

Fare and toll increases, combined with service cuts, would eliminate the $436 million MTA budget gap in 2005. There remains a $695 million deficit in 2006 and larger deficits in later years. MTA executives say that another fare increase might be necessary in 2007.

The MTA also released a $27.8 billion five-year capital program for 2005 to 2009. While most of this vast sum goes toward maintaining the existing transit system, funding is also included for much-needed system expansion projects including the Second Avenue Subway, a link to Grand Central Terminal for LIRR riders and a rail link between JFK Airport and lower Manhattan.

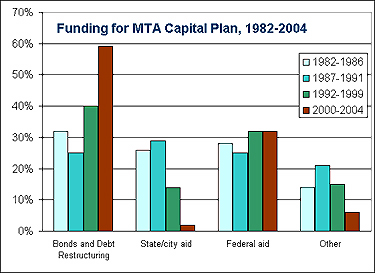

The need for another fare increase, coming on the heels of across-the-board fare and toll hikes in May 2003, shows how capital spending is related to fares. In a departure from past practice, capital spending over the past five years was funded largely by borrowing. A recent Regional Plan Association study reported that 59 percent of the 2000-04 capital program was funded by bonds and debt restructuring, up sharply from 40 percent for the 1992-99 period and 25 percent from 1987 to 1991. Payments on the increased debt load are putting pressure on the MTA budget and leading to the need for fare and toll hikes every couple of years.

The MTA's reliance on borrowing for the 2000-04 capital program was forced by cutbacks in state and city aid. The figure below shows that state and city aid covered only two percent of the 2000-04 capital program, down from about 30 percent a decade ago.

Source: Regional Plan Association

No one questions the importance of finding the money for maintaining and even expanding the current subway, bus and commuter rail system. And, despite the appeal of the expansion projects, no one doubts the critical necessity of maintaining the existing system. As former MTA Chairman Richard Ravitch, who put together the MTA's first capital program in the early 1980s that brought the transit system back from the brink of collapse, said to the New York Times, "The highest priority must be the capital maintenance of the existing system. Otherwise, the subway system and commuter rail system are going to start down the slippery slope again."

Transit advocates have long called on the state and city to resume their support of MTA capital spending. Elliot Sander, director of the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University, told the Daily News, "When the system was rescued in the 1980s, the state and city provided key financial support. They have now walked away." Gene Russianoff of the NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign, put the responsibility squarely on the governor. "If there is a fare increase," he said, "it has a name: It will be the George E. Pataki fare increase."

So where will the money come from? The experience with previous proposals for various funding sources, from a voter-rejected bond act to tolls on the East River bridges, is not encouraging. Neither the governor nor mayor want to increase taxes. The MTA was heavily criticized during last year's fare increase proceedings.

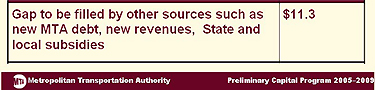

Given this backdrop, no one is talking about specific funding sources. The MTA's Powerpoint presentation on the capital program notes dryly:

The RPA report calls for "dedicated revenues" from the state, city and suburban counties and long-term subsidies from the state without providing specific recommendations. Others are even less specific. Katherine Lapp, MTA executive director, said, "The great debate will be how this need is met." Mayor Michael Bloomberg said, "We think that there are other alternatives that haven't been explored, and we wanted the staffs to do more work." A spokesman for State Comptroller Alan Hevesi told the Times, "You can see that there are some fundamental issues, particularly in terms of growing debt service. It's clear [the MTA] can't really count on something to magically come along and solve the problem."

The capital plan goes to Albany for approval and consideration of funding issues. It is anyone's guess how the governor and legislative leaders, who just now approved a state budget that was due in last spring, will address the funding challenge.

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â

Bruce Schaller is head of Schaller Consulting, which provides research and analysis about transportation, and is also a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Transportation Policy and Management at New York University.Â