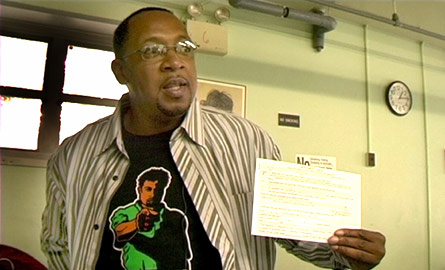

In a scene from the documentary Election Day, Leon Batts, who has a felony conviction holds up his ballot as he votes for the first time in his life. Batts' vote in 2004 was ruled invalid because of a problem with his registration, but he has vowed to try again.

Last month, the New York State Assembly unanimously passed a bill expressing regret for New York’s role in the slave trade. The move was a recognition of the state’s history as much as it was an apology. “A lot of people don’t even think slavery happened here,” said its prime sponsor, Assemblymember Keith Wright of Manhattan.

But it did. Slavery was not simply a Southern affair. Neither were the laws used to keep former slaves and their descendants from the polls. Today, New York’s laws depriving some people with felony convictions of their right to vote serve as an ongoing, painful reminder of that legacy.

Currently, under New York law, people with felony convictions lose the right to vote while they are incarcerated and on parole. They can vote while on probation. (People on parole and probation both live in the community under supervision. In some cases, after a person is convicted, the judge can sentence him or her to probation. While this can include jail time, it does not have to. Parole is granted by the parole board to a person who has served some of his or her sentences in prison and is awarded for “good behavior.’) These felon disenfranchisement laws currently bar 122,000 New Yorkers from the polls. Nearly 87 percent of those disenfranchised are black and Latino.

Origins of Injustice

New York began disenfranchising its black citizens even before the end of slavery. At the 1821 Constitutional Convention, the racial motivations behind felon disenfranchisement were clear. One delegate urged his colleagues, “Survey you[r] prisons…and what a darkening host meets the eye! More than one-third of the convicts and felons which those walls enclose are of your sable population.”

In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution guaranteed blacks the right to vote. That is, on paper. But for nearly a century, states across the nation — New York among them — continued to pass laws to prevent blacks from voting. Poll taxes and literacy tests are some of the more infamous examples of such efforts, but they are by no means the full story.

American history gives us many moments to be proud of. One was the civil rights movement, whose brave efforts led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. But while that legislation swept away most legal obstacles suppressing the black vote—for example, the poll tax—felon disenfranchisement laws remained on the books.

The Effects of Disenfranchisement

Nationwide, 13 percent of all black men cannot vote due to such laws: a rate seven times that of any other group in America. The story is nearly universal—except for Maine and Vermont, all states deprive individuals with felony convictions of the right to vote for varying periods of time. In New York City, where the criminal justice system remains particularly rife with racial disparities, the situation is especially stark. According to the Federal Household Survey, 72 percent of current illicit drug users and dealers are white, yet over 92 percent of those serving drug-related sentences in New York are black and Latino. And among defendants convicted of felonies, blacks are significantly more likely than whites to be sent to prison and denied probation.

In some areas in the South Bronx, where the Voter Enfranchisement Project is based, nearly one in five men—family members, friends, neighbors, and co-workers—will end up in prison over the course of their lives. As a result, felon disenfranchisement laws strip these communities of their most basic democratic right: a political voice.

Today, few, if any, Americans cite the need to keep blacks from the polls as an argument for felon disenfranchisement. The modern case for barring people with felony convictions from voting takes a different tact: that these people do not deserve—or cannot be trusted—to help make public policy. But if an individual has returned to our communities and is paying taxes, why should they be denied the right to participate in the democratic process?

Apart from their pockmarked origins, such laws fly in the face of the belief that our criminal justice system is grounded in rehabilitation. The right to vote is a cornerstone of democracy, one affirmed in other nations for all citizens, regardless of their criminal backgrounds. Among all Western democracies, the United States has the harshest felon disenfranchisement laws.

Ending Felon Disenfranchisement

A broad movement has emerged to restore the right to vote to formerly incarcerated people. In recent years, several states—Nebraska, Iowa, Rhode Island, and Florida among them—have elected to reduce barriers to voting for people with felony convictions. While attempts in the recent case Hayden v. Pataki brought before U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit to reverse New York’s laws on the grounds of discrimination were unsuccessful, similar suits are pending in Arizona and Washington state.

During his campaign last year, Governor Eliot Spitzer told the Better Ballots Voter Guide that he supported giving people with felony convictions who had been released on parole the right to vote. They have “been deemed fit to return to society, and deserve the right to participate in the electoral process,” candidate Spitzer said. That’s a step forward, but felon disenfranchisement didn’t change with “Day One.” In fact, the governor has not commented on the issue since.

Meanwhile, partisan deadlock in Albany continues to frustrate attempts to address even the most basic issues with New York’s voting laws. In 2006, a joint study (in pdf) released by Demos and the Brennan Center found that over one third of all election boards in New York disenfranchised even people with felony convictions who are eligible to vote by providing inaccurate information. Many of the boards, for example, erroneously tell people on probation that they cannot vote. During this past legislative session, the Democratic-controlled Assembly passed a bill to bring elections boards into compliance with the current law. Yet the majority-Republican Senate refused to introduce a companion bill.

As partisan politics continue to roadblock reform, the governor’s support for ending felon disenfranchisement is more vital than ever. Recognizing the injustices of the past is important but, given the persistence of discriminatory laws, it is not enough. As New York begins accounting for its role in the slave trade, we must continue to dismantle the legacy of racial discrimination at the polls. As an important step, the governor should issue an executive order restoring the vote to people on parole.

Te-Ping Chen is an intern and Maggie Williams is the Project Director of the Voter Enfranchisement Project at The Bronx Defenders

Â