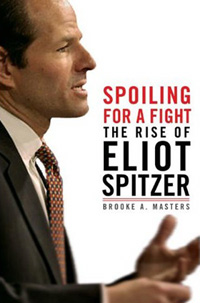

Gotham Gazette’s Reading NYC Book Club recently met with Brooke Masters, a reporter for the Financial Times whose book, Spoiling for a Fight: The Rise of Eliot Spitzer, details Eliot Spitzer’s career as New York State Attorney General. Masters talked about Spitzer’s new job as governor of the state; he was inaugurated on January 1, 1007. Below is an edited transcript.

Gotham Gazette: In the time covering Spitzer and in your time writing the book, what did you learn that you think it's important for people to know about Eliot Spitzer?

Gotham Gazette: In the time covering Spitzer and in your time writing the book, what did you learn that you think it's important for people to know about Eliot Spitzer?

Brooke Masters: This is a guy who is extraordinarily ambitious...[but] unlike other politicians I've run into who are ambitious because they want to be somebody, he's ambitious because he wants to do something. That's going to make him an interesting governor. He's going to put himself on the line and risk losing... That's what made him such a controversial and successful attorney general – he would take on cases that were not obvious winners, and that might be on the edge and controversial, because he truly thought that what he was doing would accomplish a goal that he had set for his office, or were a way he saw of improving society.

SPITZER, ISSUE BY ISSUE

Gotham Gazette: Tell us how Spitzer's experience with issues as attorney general might indicate what his priorities or approach might be as governor.

White Collar Crime

Gotham Gazette: A good place to start is his fight against white-collar crime on Wall Street. Is there any obvious way Spitzer would continue this campaign as governor? Does the office have duties of oversight on Wall Street?

Brooke Masters: Well, that's what made him famous. There are very few attorneys general that people can name, even their own, and Spitzer is famous pretty much around the country because of the white collar crime cases.

Spitzer knows that simply screaming at people isn't going to work. Whether he can avoid screaming at people, I don't know.

As governor he would appoint the folks who are in charge of the banking department, and the folks who are in charge of the insurance department, and have an overall policy role. He wouldn't be doing enforcement cases, but he would have some role in setting up rules on how banks and insurance companies treat their customers, and what the disclosure rules are. So sort of on the margins he would have an effect on that.

The Wall Street cases were a part of Spitzer's view – which he is happy to go on at length about, and does at the drop of a hat – about economic opportunity. His family went from nothing to fabulously wealthy in one generation. He believes in capitalism, he believes in the markets, and believes that government's role is making sure those opportunities are there for everybody. You're more likely to see him as governor emphasizing ways of encouraging economic opportunity in a less statist role. I think he's going to try to get away from the traditional Democratic style. Although he's probably in favor of raising the minimum wage and things like that, he will probably focus on trying to find ways to foster economic opportunity and make the markets fair.

Public Education

Gotham Gazette: What else is on Spitzer's list?

Brooke Masters: Obviously, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity solution in relation to the funding of New York City schools is a big issue. He's been given a gift, because the Court of Appeals says he only has to spend $2 billion. But he himself said it would take $4 to $6 billion. I think he'll try to come up with some compromise numbers, and try to use that in a motivating way –- there will be a caveat that a lot of the money will have to go to unusual programs like the small schools that Bloomberg has been doing.

He's not a voucher guy, but he is in favor of charter schools – that there should be competition between regulators, there should be competition between schools, and that ultimately choice is what leads to improvement, and that people should be allowed to vote with their feet. That is part of his whole marketplace idea of the world.

Medicaid

Another priority is Medicaid. Anybody who follows the state budget knows that Medicaid is the fastest growing and largest part of the state budget. It also contributes to high property taxes, because the local governments also kick in for Medicaid...If Spitzer could bring down Medicaid costs, he'll have lots of money to do other things, but he'll also win points with the suburbanites who are paying high taxes.

Another priority is Medicaid. Anybody who follows the state budget knows that Medicaid is the fastest growing and largest part of the state budget. It also contributes to high property taxes, because the local governments also kick in for Medicaid...If Spitzer could bring down Medicaid costs, he'll have lots of money to do other things, but he'll also win points with the suburbanites who are paying high taxes.

He has made a no new taxes pledge, which was an interesting choice for a Democrat, particularly one who was running so far ahead in the polls. I don't think he had to; he's doing it because he believes it. If he solves Medicaid, he can bring taxes down without hurting other things.

Gotham Gazette: Has he given an indication as to how he thinks the Medicaid problem should be solved?

Brooke Masters: He talks a lot about streamlining and technology. He got really excited the other day about trying to improve hospital information technology, so when you go to a hospital all the other tests that you've had at the six other hospitals and doctor's offices you've been to will pop up, so they won't retest you for the 25 things that you've already been tested for. Particularly for Medicaid, which is paying those bills, if you could even cut down on a fifth of the tests, it would actually amount of substantial savings.

He's also talked about trying to expand primary care to cut down on emergency room visits. Everybody likes to talk about wouldn't it be nice if there were fewer emergency room visits. But I think that he's actually interested in setting aside money to do it.

Albany Reform

Gotham Gazette: One of the things that Spitzer mentioned as a priority during his campaign for governor is so-called Albany reform – fixing how the state government actually works. Some of his critics have said that as attorney general he had the chance to deal with this but did not. Do you think that's a valid criticism?

Brooke Masters: I think it's unfair to say that Spitzer won't take on Albany simply because he hasn't taken on Albany. The attorney general, like any public official, has limited resources. And he did clearly choose to do Wall Street, rather than Albany.

Also, if you look at the staff he gathered, he did not have a particularly strong grounding in Albany. Public corruption cases require above all really good informants, really good sources, and a really good understanding of exactly how business is done. Taking it on as a prosecutor means you have to put together cases, and that is particularly tough.

As governor he might have the clout -- as someone who just won the election with a large margin of victory -- to pass lobbying reform, and agency reform, and commission reform as legislation.

Bob Zane: Eliot Spitzer has been on record as critical of public authorities. Do you think he will try to get more control and get them to be more efficient?

Brooke Masters: Yes. The authorities control so much money. If you are going to try to get the state budget under control and refocus it, you have to get the authority money or you're never going to be able to do it. I don't know if it will work, but I wouldn't be surprised to see that on his agenda in the first two months.

Henry Stern: Doesn’t he appoint the members of the authorities?

Brooke Masters: Most of them do not serve at the pleasure of the governor, so they are going to be holdovers from former Governor George Pataki for quite a while. There's a lot of skullduggery being talked about – people resigning so that Pataki can re-appoint them now, so that Spitzer won't be able to appoint their own people. There's a long history of doing that in New York.

Gotham Gazette: One goal that Spitzer put on his agenda was to reform the redistricting process, and on the uber-technical side of things, do you think he’ll be successful in that? You’ve already touched on sort of what his working relationship might be with the legislature, but do you think he actually will be able to put his foot down on that?

Brooke Masters: I think he’s going to try. But I think he's going to do lobbying reform and campaign finance reform and authority reform first. They're all an easier sell. None of the others put the legislature at risk of their jobs.

Gun Control

Brooke Masters: Gun control was Spitzer's big loss. It’s going to be interesting because he worked with Andrew Cuomo on this and they both completely failed in the late 1990s. Cuomo in particular says he's still interested in pursuing it.

Brooke Masters: Gun control was Spitzer's big loss. It’s going to be interesting because he worked with Andrew Cuomo on this and they both completely failed in the late 1990s. Cuomo in particular says he's still interested in pursuing it.

In the 1990s, New York was getting all these illegal guns from Virginia, because people would go to Virginia, buy a dozen guns – there are very loose rules there – and sell them here. Spitzer's theory was that the gun manufacturers knew full well which retailers were selling to lots and lots of people who were using the guns in crimes, and that if they just cut off a few of the bad dealers it would cut down on illegal gun crime.

He brought a lawsuit against the gun manufacturers arguing that they were creating a public nuisance by putting illegal guns on the streets. It was absolutely torched by the courts. They were not interested in this theory; they thought it was ridiculous.

It is a classic Spitzer thing to do. He takes this law – public nuisance – which is generally used for environmental cases and noise, and tries to apply it to something completely different, in this case illegal guns. It didn't work, but you might see Cuomo come back at that issue somehow. He and Spitzer both remain convinced that it was the right thing to do.

But he and Cuomo also tried to work with gun companies to see if they could get them to go along and create a screening program for retailers. It will be interesting to see if that comes back.

Gotham Gazette: As governor he might find fertile ground to work with that, since Bloomberg is so into combating illegal guns right now.

Brooke Masters: Exactly. I could see him working with Bloomberg on this. He and Bloomberg want to work together on a lot of stuff. They like one another, and they have a similar worldview. I think you'll see a lot of Bloomberg-Spitzer alliances on things.

But if you ask Spitzer to make a list of the five things he's going to do first, illegal guns are not there – as opposed to Cuomo. Spitzer's interested in crime, but he recognizes that he doesn't have that much hands-on authority on crime as governor; that's what the district attorneys and police departments and localities do.

Economic Development

Brooke Masters: Economic development upstate is also an issue. Basically we've got depressed Ohio everyplace north of Albany. Until that part of the state stops being completely depressed, that will be one of his priorities because it puts a drag on the whole rest of the state.

He wants to fix workers compensation, which seems like a real technical issue. But it turns out that New York has an extraordinarily expensive workers compensation program – the eighth most expensive in the nation in terms of the premiums that employers pay. But it is 49th in terms of payouts. Somewhere between the high premiums and the low payouts, a lot of money is disappearing. Nobody knows exactly what's wrong, but something must be. Spitzer is trying to solve that problem because he will win points with business for cutting their costs, but not hurt workers. If you eliminate the administrative costs, you could get the workers more money. It could be a win-win for everybody.

THE GOVERNOR AND NATIONAL ISSUES

Book Club Member: You've laid out a pretty strong state agenda that Spitzer is going to pursue. Do you have any sense for whether he is going to pick any national issues where he might be able to make an impact? There is a rumor in Washington that he is going to take some dramatic action in New York State that will affect the national debate on climate change.

Brooke Masters: He is already part of a lawsuit. There is a lawsuit by a lot of states arguing that the the Environmental Protection Agency is falling down on its job, and ought to be regulating carbon dioxide to stop global warming. The EPA and the Bush administration say they do not have the authority; the states say that under the Clean Air Act they have the authority and the duty to regulate anything that may affect human health. Much of the legal theory in that case was developed by staff lawyers in the New York Attorney General's Office, because it has the biggest environmental unit of any of the attorneys general offices. While it is Massachusetts that is the lead attorney, number two is New York.

Gotham Gazette: When will that case be resolved?

Brooke Masters: If they all agree, it could come out as early as March. If it's a close five to four, it will be June.

Spitzer is clearly interested in global warming. On the other hand, he has to be careful not to do too many things at once. Taking on the international debate on climate change while trying to fix Albany may not be the smartest move politically. I would be surprised if it is in his first six months to a year.

I think the other issue where he can reshape the national debate and affect New York at the same time is on Medicaid. If he can figure out a way to reform or fix Medicaid in a way that can be applied to other states, then he becomes a leading national figure in that debate.

CHANGING POLITICS IN ALBANY

Philip Angel: Spitzer was clearly on a mission when he was attorney general, while Governor Pataki was in the background. Now you have an ambitious attorney general and an aggressive governor in Spitzer and Attorney General Andrew Cuomo. Do you have sense of how those new dynamics are going to play out?

Brooke Masters: Cuomo and Spitzer are not, to put it mildly, the best of buddies. They have bad blood from the gun campaign, where Spitzer felt that Cuomo sold him up the river. On the other hand, Cuomo is dying to keep Spitzer's staff on, because frankly Spitzer attracted people to that office who would not ordinarily work for the New York attorney general's office. If Cuomo really wants to hit the ground running, he really needs to keep Spitzer's people on. So right now they have an alliance of convenience.

Henry Stern: They have united against Hevesi.

Brooke Masters: Yes, they have. Also, politically, they come at things the same way. They want to root out corruption in Albany. So if Cuomo – who has Albany connections and might actually be able to get some informers – works on arresting the bad people, while Spitzer works on reform from the legislation point of view, they might actually accomplish something and not get in each other's way.

If Cuomo spends his whole term wishing he were governor and proposing governor-type things, then there will be a lot of conflict.

But you can see there are going to be collisions. How much conflict there were be depends on whether Cuomo can pivot, and do what an attorney general does. If he spends his whole term wishing he were governor and proposing governor-type things, then there will be a lot of conflict.

Bob Zane: Do you think that Spitzer will be able to secure the cooperation of the business people in New York after prosecuting them?

Brooke Masters: I think it's complicated. Spitzer was obviously seen as the prohibitive favorite in the governor's race, but not a single business group endorsed Faso; not a single one gave him any money.

Henry Stern: Fear.

Brooke Masters: Could be straight fear. But if you talk to business people and you tell them you're not going to quote them, a lot of them say he's an ambitious guy who wants to accomplish things... maybe it would be a good idea to have him on our side. At least his job isn't going to be to be the enforcer anymore. And Spitzer is pretty good at knowing what his job is.

Upstate, there's a lot of optimism that, unlike Pataki, he actually cares about trying to fix upstate. In March, Spitzer made that comment that upstate New York is like Appalachia. The Republicans seized on that, saying it was offensive. But the response from the business community upstate was, "He's right. It is like Appalachia here. Would somebody please come fix it?"

The Wall Street folks don't like him, obviously, because he's made their lives miserable. But one of their theories is that he'll have credibility if he comes out and say we need X reforms to help make the stock exchange strong, since he's clearly not a patsy for the industry.

A COMBATIVE PERSONALITY

Gotham Gazette: One of the themes of your book is that Spitzer, while he's effective and energetic, is very combative and alienating. Can you talk about how well his personality will transfer from attorney general to governor?

Gotham Gazette: One of the themes of your book is that Spitzer, while he's effective and energetic, is very combative and alienating. Can you talk about how well his personality will transfer from attorney general to governor?

Brooke Masters: I think it will be really interesting. He's got to grow as a human being. He has been very much "My Way or the Highway." And that's not going to get him everywhere he needs to go.

On the one hand, everybody sort of believes that New York needs to change. All of the polls suggest that people voted for Spitzer because they thought he'd change things. In that way, his combative personality and his effort to shake things up could work in his favor. On the other hand, the big question is going to be when they get behind the scenes and get down to the negotiating, whether he can find a way to work with [Assembly Speaker Sheldon] Silver and [Senate Majority Leader Joseph] Bruno, or around them in a way to bring other legislators along. And I don't know that it works.

But the image that he gets angry and yells at people and gets out of control, I think it's overblown. He has more control over his temper than his critics would have you believe, but he uses it to scare the hell out of people.

That said, he is willing to tell people off, particularly people who don’t usually get told off. He doesn’t yell at secretaries, he doesn’t yell at waiters, he’s absolutely adored by the guys who drive him around. unlike many other politicians. He does yell at powerful people.

I think the big question is whether his head can control his natural instinct to be combative. That's going to be the big test for him – if he's going to be a great governor he's going to have to do that. I don't think you can really tell from his record whether he's going to pull it off. He's going to try. He knows that simply screaming at people isn't going to work. Whether he can avoid screaming at people, I don't know.

Bob Zane: Do you think that because he's wealthy, like Mayor Bloomberg, that he'll be more ethical, since you can't lobby him as much?

Brooke Masters: Maybe, because he's not going to be looking for a lobbying job at the end. On the other hand, some of the worst officials I have ever covered are wealthy people who think they are reformers, so they think the rules don't apply to them.

You could argue that Spitzer has that tendency. The campaign financing of his first two races in 1994 and 1998, the way he paid for it, it was not illegal, but it skirted every intention of the New York State ethics laws. Under these laws, you can put tons of money in your own campaign, but you can't fund your relatives' campaigns.

In Spitzer's family, the money is all with the dad. So Eliot Spitzer took out a private bank loan himself using some real estate he owned as collateral. That's legal; you can lend your own campaign money. But then his dad paid off the loan.

They were just going to get away with it until people starting asking questions about how he was paying off those loans on his salary. He finally had to say he would pay off his dad. It was not illegal because of the ways the laws were written. As for what the point of the law was – your dad can't buy you a seat – it was completely cheesy. That was one of these things where he was doing it for the good of America. You have to wonder if he's going to do it again. Hopefully he learned his lesson.

SPITZER AS GIULIANI, OR AS TEDDY ROOSEVELT?

Bob Zane: It sounds like he's a lot like Giuliani. Do you think that if he does a real good job, like Giuliani did, we'll eventually see him run for president?

Brooke Masters: Remember, Giuliani was washed up before 9/11. So let's not root for another terrorist attack, which is what made Giuliani famous.

But he's a lot like Giuliani, and in the last chapter of the book I say that Spitzer has two models he can follow as governor.

The first is Giuliani, which is sort of the "army of one." Giuliani accomplished a great deal, and pissed off a heck of a lot of people doing it, which limited his political future – at least until 9/11. But it is coming back to haunt him as he thinks about running for president.

The first is Giuliani, which is sort of the "army of one." Giuliani accomplished a great deal, and pissed off a heck of a lot of people doing it, which limited his political future – at least until 9/11. But it is coming back to haunt him as he thinks about running for president.

Giuliani is a good comparison because the two men have similar flaws. But Giuliani’s path – the I'm Right, You're Wrong, Do It My Way route – may be what the state needs. Giuliani would say, I came in as mayor and I busted heads in the unions and I busted the squeegee guys, and we did stop and frisk and alienated lots of people because someone had to save New York. And New York is now thriving. That's the model that you can really be nasty, combative, unfriendly, completely convinced of your own self-righteousness, and get stuff done. Barring an event like 9/11, it doesn't lead to long-term political success as a presidential candidate. But it might be good for the state.

The other model is Tom Dewey, who also was a completely self-righteous prosecutor, who also went into Albany and was completely combative. He vetoed something like one out of every three bills his first year. But within a couple years he realized he wasn't getting anything done and really changed his mode of operations. That's what I say when someone has to grow on the job. Dewey is a lot like Spitzer – bright, well educated, very driven white-hat prosecutor with wild national ambitions. He ran for president when he was still a prosecutor in New York, before he was governor. Dewey was able to pivot and work with the Democratic Party, and share credit.

If Spitzer does things like that, he can get lots done.

Gotham Gazette: You compare Spitzer to a lot of historical figures in New York politics. Who do you think he'd like to be compared to?

Brooke Masters: Oh, he loves being compared to Teddy Roosevelt. Spitzer has such a Teddy Roosevelt hang-up. He’s got Teddy Roosevelt pictures in his office, he quotes him – if you look at the transition New York Web site now there’s a Teddy Roosevelt quote. I mean he’s got total Teddy Roosevelt envy.

Spitzer has such a Teddy Roosevelt hang-up. He’s got total Teddy Roosevelt envy.

Admittedly, everybody’s got Teddy Roosevelt envy, because if you’re a middle-of-the-country person – which Spitzer would say he is, as a moderate Democrat — Roosevelt was the ultimate guy. He was a moderate Republican who broke with his party when his party did what he didn’t believe in. Roosevelt created the national parks, he took on big business, he revived antitrust law. Nowadays, he’s a hero.

But he was very, very unpopular at times during his early career because he was so combative. He was considered a complete nut. And I think Spitzer takes some comfort in that, too – that Teddy Roosevelt wasn’t always considered the hero.

Â